3

The Cluster Imaginary: Tools, Local Narrative and Promise

In this world of success stories, innovation awards and dissemination of good practices, cluster administrators at the local level show that they, too, are part of the game. Thus, based on a particular cluster, this chapter reveals the imaginary that is locally conveyed to public and private financiers, as well as to laboratories and businesses, to encourage them to set up there. To do this, the cluster studied uses performative instruments such as benchmarking, territorial marketing and visual instrumentation techniques; a narrative based on a particular local history that is conducive to scientific research and industrial development; finally, a series of promises linked to employment in the territory and to the innovations enabled by the cluster. All of these resources act on the representations of individuals and lead to the construction of a sociotechnical imaginary (Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun 2009), which, through the rhetoric of innovation, images and tables, promises a desirable future.

3.1. Performative instruments: benchmarking, territorial marketing, visual instrumentation

The biocluster’s Communication Department is setting in place a range of tools that showcase a high-performance, dense and collaborative biocluster through rankings, dashboards, diagrams and visuals.

3.1.1. Benchmarking or territorial mimicry

We have just seen how supranational institutions, such as the OECD or the European Union, are implementing a comparison and ranking system in order to highlight the good practices identified in their neighbors (or competitors) and to use them as a guide for the way forward. During the survey within the biocluster, these comparative analysis practices were observed on several occasions. Indeed, benchmarks are regularly carried out on other innovation sites in France in order to find exemplary clusters in the Kuhn sense (exemplar), that is, “solutions to concrete problems, accepted by the group as paradigmatic, in the very usual sense of the term” (Kuhn 1990, p. 397). It is a matter of finding an organization or territory with better performance or greater success, listing the means of achieving the same result, submitting them to decision-makers and evaluating them (Helgason 1997). The benchmarking technique, identifying and proposing the application of the most effective “recipes”, has become a form of convergence thinking (Carré and Levratto 2011, p. 371) and a powerful relay of imitation by recommendation. This convergence logic functions from a decontextualization that makes the seemingly ideal model applicable everywhere.

At first glance, this technique does not seem too restrictive, since it calls on incompletely defined and non-coercive formal frameworks (“soft regulation”) (Lamy and Le Roux 2017, p. 106). The strength of benchmarking does not lie in the diktats of management, but in highlighting the indisputedly best results it has recorded elsewhere (Bruno and Didier 2013, p. 104). It thus directs behaviors towards a mode of management from the private sector, to the rescue of “dusty” bureaucratic hierarchies, exacerbating competitive spirit and rivalries with other clusters. This import is all the simpler to carry out as we are witnessing a profound transformation of personnel in the public sphere. Indeed, there are more bridges than before between the civil service and the private sector.

The newcomers to public administration have had international careers, often moving into auditing and consulting firms, or into industry, moving more than their elders between the private and public sectors. These more hybrid careers have enabled them to familiarize themselves with new management techniques (ibid., p. 11). They are also recruited for this knowledge, as is the case, for example, for the coordinator who initiated the benchmarking in question. She has a doctorate in biology and initially had experience in research laboratories before training in marketing and working for a large pharmaceutical group in the market research and competition departments. She was able to put her experience in the private sector and her knowledge of marketing techniques to good use at Genopole. As we shall see, most of the employees who work for pharmaceutical companies have a dual background in the public and private sectors.

Although this regulation is soft and the benchmarking guidelines appear not to be particularly coercive, this does not mean that they are not applied effectively. In January 2017, the report submitted to the Regional Council that presented the new organization of the biocluster moreover emphasized the “context of strengthening regional competition in terms of incubators/nurseries”. In this context, from 2017 onwards, Genopole has been converging towards forms of organization inspired by other incubators, such as NUMA, in central Paris. In the Evry model, the incubator is called Shaker (Rise for NUMA) and the accelerator becomes Booster. The functions of the two facilities in Paris and Evry are exactly the same: they are aimed at young entrepreneurs (Genopole places particular emphasis on doctoral and post-doctoral students, inspired by NUMA’s School Lab), accompanied by mentors, coaches or buddies, depending on the name, from neighboring companies.

This standardization of innovation spaces is reminiscent of the standardization that is taking place in global cities. Take the example of port cities that promote the artistic development of their docks: Barcelona today resembles Baltimore or Belém (Fournet-Guérin 2008). In France, Marseille is also trying to imitate its Spanish neighbor, which it takes as a reference in its urban policies.

3.1.2. Territorial marketing: asserting the cluster’s symbolic capital

Paradoxically, while a standardization is largely at work in clusters or among innovation actors, at the same time each tries to highlight its own assets, most often through indicators and statistics, in particular through the production of dashboards (Bruno and Didier 2013, p. 28). These tables have a dual function: they serve as a support for decisions and the evaluation of objectives and provide a showcase to the outside world for the health of the organization. In a competitive and fund-raising context, the biocluster therefore produces annual activity reports, whose relevance depend on the indicators selected. Indeed, these cannot be exhaustive and take into account all available figures. Certain indicators are therefore selected for the figures to be both monitored and drawn attention to. In the report published in 2017, reviewing the 2016 results, there is a graph in the section entitled “Genopole contributes to the rise of French biotechnology” that presents the statistics in a positive light. At first glance, we learn that in 2016, the cluster handled 114 projects, had 644 contacts since its creation and 275 files appraised. Of the 114 projects, there were in fact 15 companies that would have joined the site in 2016, 5 files under study, 23 prospects (potential project leaders with whom Genopole were in discussion or negotiation) and, the majority, 71 companies accredited before 2016. In this respect, the biocluster also highlights the fact that 180 companies were accredited between 1998 and 2016, but does not report the total number of companies that have left the biocluster (56), mergers and takeovers (9) and those that have ceased trading (29), which represents a total of 94 companies out of the 180 accredited.

By means of these indicators, clustering involves building attractiveness on the model of a commercial brand (Lamy and Le Roux 2017, p. 107). In the same vein as benchmarking, clusters use territorial marketing policies that have been proven in the communication implemented by cities. In France, the city of Lyon was one of the pioneers, launching its anagram-shaped brand “ONLY LYON”. In the same way, Genopole has become a brand (Genopole©) that awards its accreditation to the organizations that join it. These accreditation practices are imported from the logic of territorial specialization, which gives a particular value to a place, as is the case with AOCs (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) (Harvey 2008). In a similar way, accreditation guarantees a quality specific to its location, where the advantages are linked to the concentration of infrastructures and the symbolic capital attached to these high places of global capitalism (Clerval 2011, p. 180). Indeed, clusters are very often understood to be places that are highly intensive in knowledge and excellence: “a cluster of excellence in life sciences”, according to the 2016 activity report (p. 31). The aim is to make companies want to be identified as innovative in the context of global competition. This is evidenced in particular by the Association of University Research Parks (AURP), which in the fall of 2018 awarded Genopole its “Research Park of Excellence” accreditation. This example is then revealing of the top-down logic of the global paradigm of the knowledge economy towards clusters. Accredited by the American proponents of the concept, the biocluster in turn accredits companies and laboratories.

Here, accreditation has the particularity of having both a material and a symbolic function. We will see in the next chapter that it enables its members to benefit from the cluster’s services (support, infrastructure, etc.), provided they are geographically grouped with the other accredited members. It therefore goes hand in hand with a power of territorialization. At the same time, it symbolically identifies different organizations as belonging to a common designation, a guarantee of innovation and performance. Indeed, the accreditations, whether they contain the terms “silicon” or “valley” (Suire and Vicente 2007), are based on symbolic capital or geographic charisma (Appold 2005). This symbolic capital is not only generated by the accreditation, but also by a series of images that highlight a dense and coherent campus.

3.1.3. Visual instrumentation: the image of a dense, expanding campus

In a study of progressive institutes, Pollock and Williams show how classification work, as well as the use of images, enables organizations to shape their discourse (Pollock and Williams 2010). Sainsaulieu and Saint-Martin, building on the work of Pollock and Williams, describe the toolbox of these organizations to strengthen their arguments:

Quantitative instruments and the use of numerical data, visual instrumentation such as schemas, plans, designs and photographs, or even cognitive instrumentation, such as the use of shared values or reinforcing the legitimacy or credibility of the spokesman (Sainsaulieu and Saint-Martin 2017, p. 13).

As we have just seen, Genopole uses classic techniques from new public management, such as benchmarking and territorial marketing. Through these quantitative instruments and numerical data, both private and public institutions use visual instruments to create shared representations. Indeed, the works on the imaginary concept all emphasize the mental significance of symbolic images and their impact on individual behaviors and social frameworks. Castoriadis gives as examples architecture, urbanism, festivals, or even the means of communication organized according to an imaginary which does not cease to inhabit the individuals or the groups and which in return feeds this imaginary (Castoriadis 1999). For Castoriadis, without imaginary, there is no society. It is the utopias and representations which provide a bedrock of common beliefs and which structure the social link. Imaginary is an essential component which cements society, because all of these representations form a common world of meanings for the individuals who act within it. For Gilbert Durand, the myth is considered as a cultural formation interpreting social life (Durand and Cazenave 1996) and, as for Edgard Morin, Homo sapiens is also Homo demens. Starting from an anthropological analysis of the cinema, for the latter, imaginary life enriches and organizes reality (Morin 1958). These works all emphasize the link between the strength of mental and physical images and social reality. Thus, if we take a closer look at the images disseminated by the cluster, we realize that they give a very particular representation of reality. For example, in order to give the impression of a vast integrated campus where laboratories and companies coexist, communication documents disseminate images that highlight a dense and homogeneous geography, in perpetual expansion.

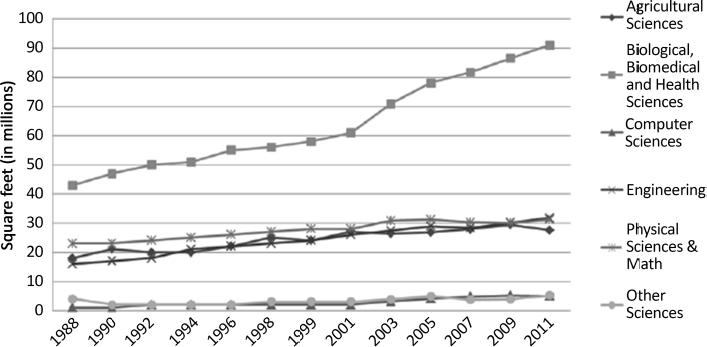

This echoes economist Paula Stephan’s survey of the U.S. research system, which shows that space dedicated to biomedical and health research structures increased by 30% between 2001 and 2011 and that square footage is becoming a performance indicator (Stephan 2015) (see Figure 3.1).

We can see the progression of the biological, biomedical and health sciences curve, which has grown from 40 million square feet in 1988 to 90 million in 2011. Occupying space appears, visually and physically, to be a guarantee of success and growth.

Genopole was the first biocluster to be created, and this precursory aspect is at the heart of the narrative put forward by the cluster. The narrative is based on three structuring dimensions that draw on both historical and current elements: Evry as a place intrinsically linked to genomics research, the economic development of the region and the need to be globally competitive.

Figure 3.1. Changes in square footage dedicated to research structures in the United States

(source: National Science Foundation, 2013, https://voxeu.org/article/us-university-science-shopping-mall-model)

3.2. The construction of a narrative

The performative instruments are thus supported by a rhetoric conveyed inside and outside the cluster, by the site’s leaders, as well as by local and national elected officials.

3.2.1. Evry, the French cradle of human genomics

In addition to performance indicators, such as dashboards and the expansion of the site, we observe a narrative shaped by both institutional communication and the discourse of political leaders. In the manner of Francesco Panese’s Human Brain Project investigation, it is therefore a case of:

Tracing the course of the main “discursive events” […] this journey will allow us to decipher the coproduction of scientific credibility and political legitimacy of a grand project shaped, between science and politics, as a prophecy based on a shared imaginary of improving the present (Panese 2017, p. 168).

The legitimacy of the governance of emerging technosciences, in order to mobilize financial, human and political resources, requires the creation of a great fiction (Callon et al. 2010), in which the new technology is necessary to solve the major problems facing humanity (world hunger, pandemics, the environmental crisis, the depletion of fossil fuels, etc.)1. The fiction of the cluster is based on a narrative of local history, which emphasizes the pioneering spirit of the creation ex nihilo of a real campus in a new city where everything was to be built. By way of example, at an event in November 2016, dubbed “Evry, cradle of human genomics”, Manuel Valls, former Mayor of Evry and Prime Minister at the time, declared:

It is in this rather unlikely place that this adventure was born and, basically, scientific research – with its dogmas and its organization, particularly in France – saw the birth of something that did not quite resemble research and, in particular, the alliance between the public and the private sector, but we had to fight. Scientific research is projects like this one. Research is also the women and men who, day after day, with this ongoing faith, experiment, compare results, publish, advance our knowledge and thus reduce diseases (extract from Manuel Valls’ speech, at the Génocentre, November 4, 2016).

Within the fiction, the problems to be solved and the proposed solutions are formulated without the need to return to the identification of these concerns (Callon et al. 2010). Here, the “alliance between the public and the private” shortens a narrative that draws on the historical past of the territory where the biocluster is located. The French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM) and its laboratory, Généthon are regularly mentioned in speeches and documents (as evidenced by the historical anchor in the 2001 dashboards, Genopole, la cité du gène et des biotechs (Genopole, the gene and biotech city))2. The cluster then follows in the footsteps of the AFM, highlighting in particular its historical affiliation with a scientific achievement resulting from Généthon: the first mapping of the human genome. Moreover, Valls uses the lexical field specific to innovation by evoking adventure, scientific discovery and the search for a better world (Sainsaulieu and Saint-Martin 2017, p. 12). We will return to this final point later. Within this lexical field, much emphasis is given to “scientific heroes” (Felt 1993; Callon et al. 2010). Indeed, the November 4, 2016 symposium organized by Genopole specifically aimed at paying tribute to the former president of the AFM, Bernard Barataud, and to the “pioneering genomics researchers, Jean Weissenbach, Charles Auffray and Daniel Cohen”, evoking “the richness of their research which has made Evry the cradle of French genomics”3. Moreover, as we can see from the words of Manuel Valls, political discourse highlights the city of Evry as “this somewhat unlikely place”:

Most accounts of the birth of Genopole on the Evry site, whether journalistic, from the main players involved in its creation, or from sociological analyses, emphasize the metaphor of the Evry area as a “desert”. The history of Genopole Evry appears to be an accident, or even “aberration”, because there is no a priori link between the territorial resources that this geographical area has to offer and the choice made by the public authorities to locate the bulk of the national genomics policy effort there (Peerbaye 2004, p. 156).

This “desert” metaphor contributes to the construction of Evry image as an outsider, a territory far from Paris and not very attractive economically, which has succeeded in gambling on attracting and developing a significant number of laboratories and companies, where most observers predicted failure. In addition to this idea of an impossible, but nevertheless challenging gamble4, the biocluster project bases part of its legitimacy on the objective of reindustrializing the territory.

3.2.2. Industrial renewal: the cluster as a solution to local economic development

The interviews and observations conducted with the biocluster’s management, as well as archival documents, highlight the cluster’s role as a remedy for the departure of companies, particularly computer companies in the 1990s (Digital, Compaq, IBM). The departure of these companies would moreover have resulted in land being made available for the installation of the cluster:

I was very aware that Evry, which was a new town, had benefited from resources to attract industrialists and that all these means had disappeared, and even today we see the same movement being perpetuated. The global management of Carrefour has moved to Massy. Crédit Agricole, which has 600 employees, is leaving Massy. It is clear that Evry was not the place… Well, it was artificial […]. All the big crates that had arrived, which is how we found buildings easily, were leaving one after the other: IBM, Hewlett Packard, Compaq, all these people disappeared. The only prospect left was Safran, and Genopole arrived in this context (interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

Genopole is a godsend for the Evry region, at a time when the cluster model is being promoted in all global and European discourse as the solution to economic competitiveness. In this context, it becomes an asset in terms of governance. Indeed, we can see that the rhetoric developed around clusters is their strength, as it persuades industrial and political-administrative spheres of the validity of the concept. Public decision-makers then have a model to implement to revive the economy. An interview with the management of the biocluster confirms this hypothesis:

As for the local politicians, Manuel Valls wasn’t there yet, but for Guyard, the people from the department and even Serge Dassault, who was already there, the idea of a major project like that, without knowing whether or not it would work, appeared to them to be a major element for the problems of image, employment, etc. All these people, from both the right and the left, got behind the Genopole project, and this remained true for twenty years […] because they had a big project to get their teeth into, so the voters, all that… (interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

Indeed, throughout the survey, regular visits and speeches by public officials confirmed this political enthusiasm for Genopole and, more generally, for the cluster concept. In the deindustrialized area of Evry, the development of the cluster is essential for the local economy, as well as for developing the image of the city as a suburb (Sedel 2009). In addition to the biocluster being necessary for local development, its existence is strongly associated with the discourse of global competition around innovation. From then on, the rhetoric insists on the urgency of aligning with North American clusters.

3.2.3. The rhetoric of technological backwardness: overcoming French scientific slowness

The legitimacy of the cluster model as a tool for adjusting between academic science and industry is also based on a rhetoric associated with the diagnosis of global competition and France’s difficulty in holding its position in the race (Callon et al. 2010). In a study on the media treatment of superconductivity between the United States and Europe, in addition to references to scientific heroes, Felt notes, on the European side, statements that alert to the delay in this technology. He concludes that, in a context of fierce competition, “selling” science has become an obligation (Felt 1993, p. 390). Thus, just as much of the promise and contemporary technoscience is based on the success stories that are currently shaping the economy and society (Loeve 2017, p. 91), Genopole is also being compared to successful cluster models. At a 2014 symposium on the theme of innovation, the then Minister of Higher Education, Geneviève Fioraso, took the opportunity to compare Genopole with the California valley and keep Genopole in the global race:

All over the world, we find this model of innovation based on large campuses, combining international universities of all sizes, research institutes and start-ups, mid-sized or large companies. This is true for Silicon Valley, where recently I saw a big company, Google, that was founded a few years earlier by students, in dialogue with a researcher in basic biology research, and it was fluid, there were no silos and no one felt threatened by the other. I think it is this type of partnership and dialogue that we need to develop in our country, which is still somewhat compartmentalized. This explains why we are lagging behind in terms of innovation, because I spoke of being in sixth place for research, but we are only in twentieth place in terms of innovation and we are considered to be more a follower than a leader, even as an intermediate country. We need to move up in terms of innovation, even if we have to put rankings into perspective, we still need to know how to tackle problems and how to respond to them (extract from Geneviève Fioraso’s speech, at the Genocentre, October 2, 2014).

To make up for this delay, the decompartmentalization of science and industry is considered insufficient. Geneviève Fioraso’s speech is a good illustration of the idea of change for change’s sake, which is the prototype of the “luring imaginary” (Enriquez 2007, cited in de Gaulejac and Hanique 2015). This imaginary consists of devaluing the current situation in order to highlight a possible future that is necessarily positive. In this framework, resistance to change appears necessarily negative and justifies the race ahead (ibid., p. 21). Thus, “arriving first” and “not lagging behind” are expressions that are frequently used and that insist on maintaining leadership (Bensaude-Vincent 2015, p. 63); as Geneviève Fioraso says, “we are only in twentieth place […] we have to move up in terms of innovation”. This type of discourse is also due to the emergence of figures among political leaders who, because of their background, are sensitive to the rapprochement between science and industry. Geneviève Fioraso, for example, was an executive in a start-up that was spun off from the CEA and then research deputy for the city of Grenoble (Vergès 2014, p. 245).

This rhetoric of emancipation from sclerotic structures5 is part of a regime of technoscientific promises that must be legitimate and credible. In the first instance, problematization aims to provide ready-made answers and solutions to a problem that has already been identified. Joly points out that the more serious and urgent the problem, the more legitimate the promise of improvement. He uses the example of the urgency and importance of maintaining a position in global competition (Joly 2015, p. 38). From then on, any form of resistance to this narrative appears as resistance to modernity and common sense. Thus, the biocluster’s communication endeavors to put into words and images a model that is difficult to contest. Its unquestionable character is strengthened by promises that announce a bright future in terms of progress and innovation.

3.3. Promises of innovation and employment at the territorial level

The synergies made possible by geographic clustering hold promises on two levels: innovation and job creation at the local level.

3.3.1. The promise of the biocluster: a sustainable environment and the medicine of the future6

The context of economic competitiveness, as we have just seen, legitimizes the action of states, which make a selection in the funding of research by subsidizing “sectors deemed to be promising, priorities, such as biotechnologies, materials sciences, nanotechnologies or neurosciences” (Audetat 2015b, p. 12). These disciplines are emerging, not only because they are deemed to bring about innovation, but also because they proclaim themselves capable of responding to the challenges facing the 21st century, such as global warming, world hunger, disease, etc. (Joly 2015, p. 39). Indeed, the new public management, by generalizing calls for projects as conditions for research funding, mainly through the ANR, has led researchers to deploy arguments in order to obtain these funds (ibid., p. 7). These arguments have a strong tendency to construct scientific promises in order to win the support of financiers, whether private (venture capitalists) or public (ANR, competitiveness clusters, EU, etc.). The growth in the production of these promises does not only concern researchers, but seems to be a phenomenon that affects innovation actors in the broadest sense7.

Following the lead of laboratory communication departments, which are seeing an increase in staff (Audetat 2015a, p. 76), clusters are also strengthening their communication around emerging science and technology regarding their ability to transform the world and solve its biggest problems. In 2017, the Genopole structure provides 9% of its budget dedicated to communication, which represents a considerable package of €841,0008. In a context of technoscientific capitalism, the promise becomes a specific mode of communication (Sunder-Rajan 2006) and, as we have just seen from the creation of the cluster, this department devotes a large part of its strategy to a “promising communication” that consists of elaborating prospective narratives (Quet 2012). Also, in this context, the communication department relies on the emergence of organizations, already mentioned above, such as progressive institutes, communication agencies, etc., specialized in the production and commercialization of knowledge oriented towards the future (Pollock and Williams 2010, p. 525). Indeed, a closer look at the press release for the “Vivre l’innovation aujourd’hui et demain” (Living Innovation Today and Tomorrow) conference to celebrate the biocluster’s 20th anniversary shows that it was written by both Genopole’s institutional communication department and the firm Andrew Lloyd & Associates, which provides strategic communication services to “leading companies and organizations involved in a wide range of emerging technologies”9, including biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, electronics, photonics and aeronautics.

As early as 2003, the communications department developed a storytelling approach (Quet 2012) with the publication of a book devoted to the five years of the cluster Il était une fois Genopole (Once Upon a Time There Was Genopole)10. The chapter entitled “Un avenir prometteur” (A promising future) predicted, even then, that the cluster would be “inventing the medicine of tomorrow” (ibid., p. 28), thanks in particular to the establishment of the Centre Hospitalier Sud Francilien (South Paris Hospital Center) near the campus, following the merger of the Evry and Corbeil-Essonnes hospitals. This move promises that patients and their families will be able to rapidly benefit from discoveries and innovations due to the proximity of the cluster’s companies and laboratories. In 2003, Genopole’s communications, strongly influenced by the identity of the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM), were also part of a unifying belief in the fight against disease. The first dashboards, communication documents and the website, are built around the mantra “Succeeding together in biotechnology” which extends the foundations laid down by the AFM. Recently, it has been replaced by the fashionable term “innovation”, with the slogan “Vivre l’innovation. Innovation today, every day”. In the activity report published in 2016, the various themes presenting Genopole’s activities are called “resource creator”, “project federator”, “idea developer”, “technology cultivator”, etc. These names are taken from the vocabulary of innovation already mentioned: adventure, scientific discovery, the search for a better world, etc. (Sainsaulieu and Saint-Martin 2017, p. 12). Beyond this lexicon, the promise made by the biocluster in supporting biotech companies and life science laboratories (many of which conduct health research) is to offer a sustainable environment and the medicine of the future. The 2016 report thus states, “Genopole contributes to hatching the innovations that will improve our health, living conditions and environment” (p. 3). Alongside this prediction that society will be better off as a result of the innovations produced by the cluster, there is a promise of job creation. Indeed, by 2025, the biocluster plans to “become the capital of genobiomedicine”.

3.3.2. Becoming the capital of genobiomedicine, creating jobs for innovators

In the same way that the European institutions have set up the, as its name suggests, future-oriented research and innovation program “Horizon H2020”, the biocluster has also set up a forward-looking strategic plan called “Genopole 2025”. In 2011, Thierry Mandon, then President of Genopole, recalled the context in which this strategy was developed. Having discussed once again the successful challenge of converting the region and the biocluster’s national reputation, he insisted on positioning the cluster at a global level through the Genopole 2025 strategic plan in order to generate the confidence of public financiers:

We have therefore launched a study on the future of Genopole up to 2025, with a view to it becoming a major player on the world stage. This reflection has focused on strategic directions and on the new mandate we need to seek from our partners: the state, the region, the department, the Evry agglomeration community, the major research organizations and all our partners from day one. By drawing up this Genopole 2025 strategic plan, we will be able to renegotiate a new commitment with the public authorities up to 2012 and to answer certain questions about resources […]. On this basis, we will be able to enter into a new contract with our financiers and encourage them to understand that the transformation of Genopole into a world-class cluster requires a concentrated effort. France invested, but was quickly overtaken by the United States, Germany and England. It must therefore reflect on its ambitions by 2025 and concentrate the related resources (extract from the speech by Thierry Mandon, president of the biocluster, at the General Assembly of the cluster’s leaders and decision-makers, Genoforum 2011, December 16, 2011).

This extract from the speech accurately reflects the funding mechanism highlighted by Van Lente and Rip under the term “strategic science” (Rip and Van Lente 1998). The rhetorical space used by the biocluster produces promises aimed at capturing resources on a competitive basis with respect to financiers: “to encourage them to understand” the “concentration of efforts” in the face of “the United States, Germany and England”11. The dominant promise is to make Evry “the capital of genobiomedicine”12. This is a neologism commonly and almost exclusively used13 by Genopole to refer to the future challenges of medicine using a genome analysis approach. To achieve this, the cluster has broken down its Genopole 2025 plan into eight objectives14. In addition to promises relating to the development of new technologies, working methods, land acquisition, etc., the biocluster’s vision is based on a figure who embodies the harmonious combination of science and industry, the entrepreneurial researcher or heroic innovator (Callon et al. 2010), with both scientific and entrepreneurial qualities and always in search of innovation15. This anticipatory account of a generation of innovators in the making is clearly evident in the words of the French Education and Research Minister during her visit to Genopole:

We must know how to make the most of our assets in order to build together this model of innovation that creates jobs and progress […] and I will conclude by quoting Seneca: “It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare; it is because we do not dare that they are difficult.” This is how we must act now in France, to take initiatives, to transmit the taste for risk to young people, because if we no longer have this taste for innovation, if we hide behind the precautionary principle, which is useful but must not become a principle of inaction, then we are not proposing a future in which young people can project themselves and we cannot be surprised that they go to countries that, in turn, become more pioneering. Let us find this spirit of adventure, this spirit of risk, this taste for daring, this is how we will build a world that is fairer, more creative and a provider of more jobs and progress. Thank you for contributing to this (extract from Geneviève Fioraso’s speech at the Génocentre, October 2, 2014).

This heroic and adventurous spirit, in addition to being promised, is even invoked: “we must know”, “this is how we must act”, “let us find out”. However, above all, it illustrates a dimension developed by the sociology of expectations that links promises to the calculations of public investors with the concept of promise requirement cycles (Van Lente 1993). These “cycles of promises and requirements” show how promises are put forward and then how they, in turn, create demands, even requirements.

The cluster then uses the promise of employment in a logic of resource capture that it regularly recalls. For example, the dashboard released in 2017 promises the following future:

Genopole aims to develop a world-class biocluster on the Evry-Corbeil site and to become the European capital of genobiomedicine and bioindustries by 2025. Its objective is to bring together 30 to 35 research laboratories and 130 companies, representing 4,000 to 5,000 people (2016 biocluster activity report, Vivre l’innovation. Innovation today, every day, p. 14).

For nearly seven years, communication documents have predicted these numbers. However, a closer look at the statistics, presented by the cluster a few pages later, reveals the difficulty in keeping the promise.

Between 2005 and 2016, the cluster’s workforce grew from 1,827 people to 2,475, an increase of 628 people in 10 years. Over the same period, between 2016 and 2025, the biocluster promises to double its workforce, which would represent an increase of 2,500 people. There is therefore a clear gap between the actual increase in staff and what the institutional communication promises, in the same way as some observers have noted the growing gap between promises and actual innovation in the pharmaceutical and nanotechnology fields (Audetat 2015a). In this case, the cluster has failed over the years to fulfill its commitment in terms of jobs. Given these limitations, how can we explain the fact that the developed narrative is not running out of steam?

3.3.3. The naturalization of the cluster effect: an unquestionable concept?

Questioning the nature of the narrative developed by the cluster leads us to question the sustainability of the proposed imaginary. On the economic side, Frédéric Lordon developed the principle of the strength of simple ideas in economics (Lordon 2000, pp. 184–187). According to Lordon, these simple ideas can take the form of a watchword, synthesizing the overall project (e.g. “stability”). In the same way, innovation is a watchword, while it is reified and naturalized, without being questioned since it is posed upstream of reflections (Sainsaulieu and Saint-Martin 2017, p. 17). Indeed, the promise is embodied in a self-fulfilling prophecy that naturalizes technical change (Callon et al. 2010). This naturalization takes place in common places such that “if the necessary resources are gathered, the technique will ineluctably bring solutions”, or “if we do not invest in this technology, others will do so before us”. It is then difficult to conceive alternatives to this kind of prognosis.

A critic, like Lordon, of the use of the lexical field of ease, Granger believes that the knowledge economy has “the simplicity of beautiful theoretical nesting” (Granger 2015, p. 65). He then takes up the criticisms regularly directed towards higher education, as noted by Christian Laval in Le nouvel ordre éducatif mondial (The new global educational order), again beginning with the conditional conjunction “if”: “if there is unemployment in France, it is because university training is not adapted to the needs of business”, or “if the economy is at half-mast, it is because research is too academic, too fundamental and barely oriented towards bringing innovative products or concepts to market” (Dardot and Weber 2002). These cause-and-effect relationships (if such and such a situation either does or does not exist, we must expect or rely on such and such a situation) call upon laws that conceptualize their naturalization: Moore’s law, Gabor’s law, etc. (Callon et al. 2010). Moore’s law, in particular, appears to be a matrix of technoscientific promises, as a metaphor for technical progress in general (Loeve 2017). Indeed, this law derives from a prediction by Gordon Moore, a computer scientist and co-founder of the Intel corporation, who predicted that the number of transistors, the main components of processors, would double every two years.

In his article “La loi de Moore: enquête critique sur l’économie d’une promesse” (Moore’s Law: critical analysis of the economics of a promise), Sacha Loeve shows how this law is a prototype of a technological roadmap that brings together a diversity of actors towards a common cause. Its naturalization is such that few people have been interested in its construction and validity, the only questions being of the “how to keep it going?” type. By shedding light on the fabric of this law, Loeve shows how this prophecy was constructed after the fact. To Loeve, it is not an industrial lie but an invention of the present that modifies the meaning of the past, which creates “the possible behind itself” (ibid. p. 110) and thus turns into a perpetual promise. Also, similar to the common places highlighted by Dardot, the credibility of the cluster is intimately linked to the simplistic naturalization that results from it. In his case, the prophecy is as follows: if companies, laboratories and training are grouped together geographically, the synergies between researchers and industrialists will be strengthened and will lead to innovation. This principle would then constitute what Genopole managers have referred to throughout the survey as the “cluster effect”16, evading the idea that this law can be disproved in reality:

But because I believe in the cluster effect […]. For me, a cluster is a place where you can go to a conference without difficulty and exchange with other people without problems. That’s why I insist on a sufficient critical mass […] so the idea is to reach what I call an irreversibility threshold of people on the site. In Sophia Antipolis, no one notices when a company leaves, so the idea is to get to that point as quickly as possible, because it’s something I fear, to see the funds granted to the PIG for its development. For me, it is essential to reach these decisive steps that I estimate at 4,000/5,000 jobs, roughly 150 companies […]. I remember the Christian Blanc report, which really hit me. Michael Porter, I already knew… I had the cluster effect in my mind as far back as 2004. And above all, I had to distinguish between the Genopole cluster and the Medicen competitiveness pole, which I was partly in charge of at the time, by saying that a cluster is more restricted, whereas a competitiveness pole is more diffuse, more global. They’re not on the same scale! (interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

On the one hand, there is a fairly advanced conceptualization in these remarks, “cluster effect”, “critical mass”, “irreversibility threshold”, and, on the other hand, two reference figures: on one side, the figure of the North American expert theorist, Michael Porter, and the political figure at the origin of the assimilation of the concept in French public policies, Christian Blanc. The law described here is based on the idea of entrainment found in economics on the network effect in certain technologies, such as communication services, which considers that the technique passes through network exchanges that represent the source of the mechanism that causes this type of effect17. The cluster effect is then based on the economic idea of positive externalities: the mutualization of equipment, the grouping of skills, the intensification of exchanges, etc. The last of these is the black spot of many clusters. While most have succeeded in bringing together scientific and industrial skills and cutting-edge infrastructures, few of them spontaneously see the interactions developing within them and stick to the benefits in terms of marketing, brought about by accreditation practices.

Ultimately, belief in the promise of the cluster effect is not actually oriented towards a desirable future, but serves more to pull the present along (Bensaude-Vincent 2015, p. 63). This promise embodies more of a “rational mobilizing myth” (Hatchuel 1996) that allows for the coordination and federating of actions (the national program on precision medicine, for example), the setting up of infrastructures such as shared platforms, the mobilization of researchers in business creation processes, etc. Thus reified and naturalized, it becomes difficult to question it. Indeed, throughout the immersion survey within the cluster, the simple idea of cluster effect, in Lordon’s sense, was so strong that it was never questioned. The common belief, shared by the different layers of managers, was that if the cluster effect is not working optimally, it is because Genopole has not yet found the modalities for its application in its territory. Indeed, in the second part of this book, we will see how the cluster has been trying, since its creation, to develop interaction between science and industry in an iterative process, through a system of networking.

- 1 In particular, Pierre-Benoît Joly has highlighted how GMO advocates have had to justify that there is no alternative worldwide to this technology to combat hunger when it is really a question of distribution, not availability (Joly 2015, p. 38).

- 2 https://www.genopole.fr/IMG/pdf/plaquette_genopole_fr_020531.pdf.

- 3 Genopole’s youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZejcVGzSEy8.

- 4 This rhetoric also flooded the media on the occasion of Pierre Tambourin’s departure at the beginning of 2017: the press articles recounting his career and based on his words highlight Evry as both a virgin zone and a minefield for the development of biotechnologies.

- 5 Expression borrowed from Arnaud Saint-Martin during his intervention “Duality, plasticity, duplicity: contemporary uses of satellite observation techniques” at the Journées scientifiques du center Pierre Naville, Sciences et émancipation. Ce que font les sciences à la société, December 7, 2017.

- 6 In a communication brochure posted on March 2, 2018 on the Genopole website, the two strategic axes are “a sustainable environment” and “the medicine of the future”. Available at: https://www.genopole.fr/IMG/pdf/2018_genopole_plaquette.pdf (p. 5).

- 7 Several works in sociology and economics emphasize the weight of expectations regarding research and development investment in the formulation of promises (Rosenberg 1983; Dosi 1988). Marc Audetat insists on the development of a sociology of expectations (Audetat 2015) or sociology of expectations (Brown 2003; Borup et al. 2006) that focuses on the way in which the research funding system gives rise to predictions that rely on imaginaries that come to justify the promises made (Joly et al. 2010; Jasanoff and Kim 2015).

- 8 Figures presented at the PIG staff meeting on February 28, 2017.

- 9 http://www.ala.com/clients/.

- 10 The chapters of the book can be downloaded at: http://www.genopole.fr/Le-Livre-anniversaire-des-5-ans-de.html#. WNEKuxI19EI.

- 11 Not to mention the subnational competition.

- 12 media.genopole.fr/medias/domain1/media113/18142-v7m2uij2nl.docx.

- 13 A quick search on the Internet shows that the term only refers to web pages dedicated to Genopole.

- 14 The eight objectives of Genopole 2025 can be found at: https://www.genopole.fr/Notrestrategie-a-l-horizon-2025.html#. WqejfBPOWi4.

- 15 Genopole has been honoring these innovators even more since 2011, with the creation of the Genopole Young Biotech Award, which rewards the young start-up entrepreneurs who are supported by the cluster.

- 16 “Genopole creates the right conditions for meetings between the site’s players, companies and laboratories, which is a necessary condition for creating the biocluster effect.” Genopole-creeles-conditions-favorables-aux.html#.WqpNbRPOWi4.

- 17 For example, the value placed by a consumer on a network service increases as the number of consumers of that service increases: https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/externaliteeconomie/#i_55668.