CAHPTER 5

OUT OF THE ASHES

At the outset in 1975, Bogle’s fledgling Vanguard had only a minor, mechanical business administering barely $1.4 billion of assets in a midsize group of mutual funds that were steadily losing assets. The 11 Wellington funds had experienced net redemptions by shareholders for 40 consecutive months, a trend that would continue for 40 additional months until January 1978. Total net cash outflow totaled $930 million, or 36 percent of the funds’ assets.

Bogle would recall the time as “the ghastly period of attrition.”

Even worse, the fledgling company had no control over its future because the success of every mutual fund organization depended on two major functions: investing and selling. Vanguard had zero role in either. For both selling and investing, it was totally dependent on Wellington Management Company, the organization that had fired Bogle and left him adrift in an investment storm.

But Bogle, ferocious to succeed, declared that Vanguard’s small size freed it to be flexible and innovative in developing its strategy. He later recalled, “Our challenge at the time was to build, out of the ashes of major corporate conflict, a new and better way to manage a mutual fund complex.” The Vanguard Experiment, as Bogle described his new venture, was designed “to prove that mutual funds could operate independently, and do so in a manner that would directly benefit their shareholders.”1

Bogle characterized Vanguard’s early strategy as “a generous dose of opportunism” plus “a touch of disingenuousness”—surely euphemisms—plus the essential “heavy measure of determination.” But all those words came to Bogle after long years of struggling to achieve success. For any realistic observer at the time, his next move was easily defined as folly.

Bogle had put Jim Riepe in charge of fund operations—supposedly Vanguard’s core business—so Bogle could focus on business strategy and communication with fund shareholders and the media. He was searching for any way to get around, or under, or over, the constrictions of his agreement not to sell or manage mutual funds. Looking for innovations and innovators, he called Dean LeBaron, the creative head of an exciting young investment firm already known as a serial innovator: Batterymarch Financial Management. Both men’s firms were small and unusual enough to be much talked about by members of the investment community. “I’ve heard a lot about you and your firm,” opened Bogle. “We should get together to see if there might be a way we could work together.”

“Sounds like a good idea,” LeBaron quickly replied. “When?”2

They bonded on several levels. Both were mavericks and innovators. Both were self-described tightwads interested in minimizing costs. Both were good at attracting public attention and enjoyed the admiration. Both were bold entrepreneurs.

LeBaron was a pioneer in international investing, particularly in the emerging markets of China and Russia and the countries of South America that were starting to ease their taxes on foreign investors and loosen limits on repatriating profits. Accounting standards were notoriously lax in these markets and research reports by capable, objective securities analysts were nonexistent. Local insiders were sure to get all investment news, good or bad, long before outsiders.

Typically, LeBaron saw potential advantages behind all these obstacles. If Batterymarch could find ways to work around or even exploit problems that caused most institutional investors to stay out of Latin America, the firm would have little or no competition in a highly inefficient market. LeBaron decided Batterymarch would conduct its own primary market research and make itself a market leader. He recalled, “I urged Jack to diversify internationally in order to reduce investment risk, but he never felt comfortable with international investing.”

Bogle’s weak heart added to his hesitancy. “Jack said he was willing to go to Latin America, but I would personally have to take CPR training and travel with him in adjoining seats on the same planes, and sleep in the same room in hotels. I agreed, but we never actually went.”

LeBaron respected Bogle for several reasons. One was the unusually high quality of directors attracted to Vanguard, particularly in an era when so-called independent directors were often no more than cronies of the people in power at the mutual fund management companies. He also liked the innovative concept that the mutual funds collectively owned Vanguard.

Bogle admired LeBaron’s refusal to allow his institutional clients to allocate commissions on Batterymarch trades to their preferred brokers. He believed that if brokerage commissions were so high that they had “currency” value, that value should be captured by the pension funds his firm was managing. Institutional brokerage commissions in the early 1970s, before rates could be negotiated, averaged 40 cents a share versus 1 to 2 cents today and were widely used as “soft dollar” currency to pay for all sorts of services, almost always for the economic benefit of market insiders, not investors.

Bogle also respected LeBaron’s policy that Batterymarch would “call ’em as we see ’em” when voting on proxy issues for companies its funds owned, never influenced by whether the company was also a client. Batterymarch voted against all directors who authorized greenmail—buying enough shares in a company to threaten a hostile takeover so the target company would instead repurchase its shares at a premium3—and also did so at every other company where they were directors. This resulted in a distressed call from the chairman of a Batterymarch client. “Dean, do you realize Batterymarch is voting against me?”

“Yes. We have a strict policy of voting against any director who, at any company, approves greenmail.”

“If that’s your final position, Dean, you’re fired!”

“Understood.”

LeBaron’s cost consciousness delighted Bogle, as did his irreverent attitude toward conventional investment organizations. Both men felt management companies’ fees were too high and that investment managers were overpaid, overly focused on their own compensation and too little focused on serving clients.

Both Bogle and LeBaron were facile with figures, so they knew that most active managers were not beating the market. Instead, the market, after costs of trading and management fees, was increasingly beating them. Adopting the simple strategy of “if you can’t beat the market, join it,” both were intrigued with the new idea of market-matching index funds. Academic studies, and a recent Newsweek article by Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson,4 gave strong theoretical support to indexing. (Index funds carefully replicate the capitalization percentage weightings of all the stocks in an index of a major stock market, such as the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, by adjusting those weightings as prices change. Index funds can also seek to track segments of the market, such as growth stocks or small-cap stocks.)

Batterymarch and a few other firms had developed index funds for the institutional market, even though they stretched financial regulations.* In those days SEC regulations required a qualified senior officer to sign off on every trade, which was impossible for index investors. SEC chairman John Shad told LeBaron, “It is illegal, but we’ll let it go on. You’re well intentioned but probably misguided.”

No firm was offering an index mutual fund to individual investors, but both Bogle and LeBaron thought a retail index fund for individuals was an idea whose time had come.

Bogle was sure he had seen a crucial opportunity. An index fund needed no company or industry research to estimate future earnings and no expensive portfolio manager deciding which stocks to buy or when a new portfolio strategy was required—or even permitted. Once a stock market index had been created by a third-party organization, an index fund simply and obediently reproduced it in a basket of securities. Indexing could be a breakout strategic move for Vanguard. Bogle was determined to get approval from his board of directors to launch First Index Investment Trust—the first index mutual fund.

He surprised the board in September 1975, just four months after Vanguard’s launching, with a strong pitch to create this new kind of mutual fund—a passively managed fund guaranteed never to beat the market. Industry opponents soon derided the concept as the “the pursuit of mediocrity” or a “formula for a consistent long-term loser.” Who would want to settle for just average? Who would ever aspire to be passive? Bogle, as usual, led with the numbers. In seven of the 10 years from 1964 to 1974, the S&P index beat more than half of the active managers and over the full decade it outpaced 78 percent of them. Three-quarters of stock mutual funds had failed to keep up with the market! That meant that, in the competition for investment performance, an index fund would be a “top-quartile” winner.

Introducing the first retail index fund as “first mover” appealed to Bogle. As with other strategic moves in those early years, he would meet strong resistance from his board. Only his creativity, his stubborn persistence and his facility with numbers would win the day. He carefully centered his case on a language technicality crafted for his specific purpose: an index fund would not need any investment management. An index fund would only need basic administrative capabilities. With skillful execution or trading, it would replicate an independently established stock market index like the S&P 500. By this logic, an index mutual fund would—if only just barely—avoid violating the limitations of Vanguard’s narrow mandate; Vanguard would now have a mutual fund without “investment management.”

After months of consideration, Vanguard’s directors formally agreed in May 1976 to move forward with an SEC filing of First Index Investment Trust. Difficult as it may have been to sell the fund directors on indexing, that was far from the highest hurdle Bogle would face. Next, he had to sell Wall Street on his new fund idea; this would be much more challenging.

Despite Bogle’s heady hopes, investment bankers were not at all excited about the opportunity to underwrite the new fund. They had many good reasons: Vanguard was an unknown firm and certainly not an important client for Wall Street. The great bear market of 1973–1974 had drawn the Dow Jones Industrial Average down by nearly 50 percent, and far worse after adjusting for rampant inflation. Retail investors remained shell-shocked. Indexing meant “settling for average,” hardly a compelling selling proposition. Worse, the new fund would be offered with an 8½ percent load or sales charge. This cost guaranteed that investors would start out significantly behind the market and could never, ever catch up.

Having won the approval to launch an index fund, Bogle’s first move was to call a man who knew all the Wall Street barons: Wellington’s long-serving senior trader, Jim French. “Frenchy, I need your help. Which Street firms can we get to underwrite an index fund?”5 After some thought, French gave Bogle a list of firms that were proven “friends of Wellington” and had strong retail distribution.

Bogle’s second call was to Vanguard’s Jan Twardowski, a young “quant” (mathematically focused) investor who would be in charge of the actual indexing. Twardowski said he would need to have sufficient capital in the new fund to be able to replicate the S&P market index. The more the merrier.

It took Bogle all winter and all spring to organize the initial public offering. Finally, he persuaded Dean Witter to lead the underwriting, with three other firms, aiming for an IPO of $150 million in the spring of 1976. To drum up demand among stockbrokers, Bogle covered the major centers like Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, while Riepe was assigned to smaller cities like Detroit, Sacramento, Buffalo, Minneapolis, Austin, and Memphis. Both men learned that the demand for the new fund was, well, limited.

Based on the lack of interest, the original goal of $150 million was reduced to $75 million.

As they met with more brokers, nearly all of the questions they received were negative. “Why should we sell a fund that’s never going to beat the market?” “Where is the excitement in a fund that has no focus, requires no skills, has no charismatic portfolio manager, and buys everything?”

That $75 million sales goal was cut again to $40 million.

A Minneapolis broker printed posters and sent them out to active managers. Below a picture of Uncle Sam based on patriotic wartime recruiting posters was a clear statement: “Index Funds Are Un-American!” Brokers asked yet more questions: “Index funds are having tough times selling into the institutional market, so why do you expect success at retail?”

When the fundraising target was reduced to $20 million, the question for Vanguard changed to a worried query for Twardowski: Is this amount too small for accurate index replication?

At $20 million and then at $15 million, Twardowski’s assurances changed to a conditional positive: “We would need to sample the smaller stocks rather than deliver full replication, but that should not make a major difference in fund performance.”

“Are you sure?”

“Pretty sure,” came the hopeful response.

The IPO was a flop.

In August 1976, Bogle’s index fund raised less than 10 percent of the originally intended amount—only $11.4 million.6

Bogle had been wrong: wrong on product design and wrong on selling strategy and wrong on timing—in retrospect, by 10 long years.

This amount of assets was much too small to earn enough in fees to cover operating costs and too small to invest proportionally in all 500 stocks in the S&P index. The problems were obvious in retrospect: most retail investors had never heard of index funds. First Index Investment Trust’s name had no sex appeal for brokers or investors. With a front-end sales load deducted from an investor’s invested assets, the fund could never overcome that initial handicap, and it also had a high expense ratio (the management fee paid by fund shareholders), particularly for an unmanaged mutual fund. It was a surefire loser.

While it was a highly visible commercial failure, soon dubbed Bogle’s Folly, Bogle would years later claim it to be . . . “an artistic success.” In a history of Vanguard’s indexing, Bogle euphemistically described the seriously disappointing amount raised as “the seed capital we needed” and added, “We were ecstatic at the crucial fact that we now had our index fund.”7

Even if nobody else did, Bogle saw that it was at least a start. It cracked the board’s prohibition against Vanguard’s managing investments. Cleverly, Bogle soon merged another fund Vanguard administered, Exeter Fund, into the index fund, thus increasing its assets by $58 million and, with market appreciation, to nearly $90 million. With this merger, the fund was large enough to own at least some of all the 500 different shares in the S&P Index. After six long years, assets lumbered up to $100 million in 1982. One unexpected marketing problem: in those years, unlike most, about three-quarters of actively managed equity funds outpaced the S&P 500 and therefore also beat First Index. Eventually, in a rising market, the S&P resumed outperforming most actively managed funds, and the index fund’s assets finally climbed to $1 billion in 1988—12 years after its launch.

Part of Bogle’s positive lens on reality had long been to think ahead and strive to innovate; another was his amazing ability to look back on experience through rose-colored glasses. He certainly did this with indexing, and after indexing finally became mainstream, he took greater personal credit. By 1996, after Bogle’s retirement as CEO, Vanguard had 19 domestic index funds holding a total of $24 billion. Its international index funds held another $2 billion. Vanguard was home to nearly 60 percent of the industry’s total index fund assets.

Bogle’s next strategic move would eventually disrupt the core of the mutual fund business: sales, or distribution. He wanted to drop the traditional 8½ percent sales commission (load) and go no-load by offering shares directly to investors. This would roil the brokerage industry and, more importantly to Bogle, escape dependence on Wellington Management for distribution.

Bogle had been unrelenting for years in his drive to reduce the fees Vanguard paid to Wellington. In each confrontation, his two linked objectives were the same: to get a better deal for Vanguard and to punish Wellington for unseating him. Fees paid to Wellington were too high, he declaimed. Wellington’s incremental costs for Vanguard were so low that a fee reduction was “obviously” called for. Wellington should offer Vanguard the lower fees paid by pension funds for similarly large accounts. And later, once Vanguard took on all the intensive work of distribution and investor service, the “only” thing Wellington Management contributed was portfolio management. Whatever his particular argument, Bogle always had extensive quantitative evidence to polish his case.8

J. P. Morgan famously opined that for every major business decision, there were almost always two reasons: a good reason and the real reason. Bogle’s real, unstated motivation was getting even. Damaging Wellington was deliberate. He seemed not at all worried about weakening the investment manager Vanguard still depended on. Over time, Bogle got Wellington to make more than 200 small or large cuts in in fees paid by Vanguard.

Bogle’s push to go no-load was a stunning break with the mutual fund industry and painful to Wellington Management Company. The 8½ percent sales charge paid to brokers who pushed customers to buy funds was the mutual fund industry norm 50 years ago, and Wellington Fund depended on it. In addition, Wellington paid out substantial commissions to brokerage firms to buy and sell securities for the funds. By directing these lucrative trades to certain brokerage houses, Wellington sought a quid pro quo arrangement from the same brokers to favor Wellington’s funds when selling to investors.9 Such behind the scenes “customers be damned” reciprocal “soft dollar” relationships were pervasive in the mutual fund industry.

None of this was outside the range of accepted practice of the time. That made Bogle’s proposal to switch to no-load seem particularly radical. No-load funds were not widely offered except by large investment counseling firms, which did not see themselves as mutual fund firms but rather as investment advisers for institutions and wealthy families. These firms, including T. Rowe Price, Loomis Sayles and Scudder, Stevens & Clark, used their no-load mutual funds only as an administrative accommodation, a convenient, low-cost way of meeting the demand for investment services for such small accounts as the grandchildren of valued clients. A few of these investment counseling firms had been welcoming almost any investor who wanted to invest in their no-load mutual funds, but the major mutual fund organizations continued to impose sales loads.

The risks of Bogle’s plan were obvious and large. Angry retail brokers would almost certainly stop selling the Wellington mutual funds. They might even urge their customers to switch out of the Wellington funds, which were already shrinking, into other firms’ load funds, accelerating redemptions and loss of assets and revenues. And what if Vanguard gained little or nothing in new sales if individual investors didn’t flock to it when it dropped the sales loads?

Later Bogle claimed, “I had always had an affinity for the no-load business,” despite his two full decades of being out in front forcefully advocating Wellington’s traditional, hard-sold load funds. Now, he argued that future trends favored going no-load: investors were becoming wealthier and more knowledgeable and sophisticated, and surely would realize the benefits of no-load funds.

Over the course of two days, February 7 and 8, 1977, after many doubts and long debates, the funds’ directors increasingly saw merit in Bogle’s case. They eventually accepted his tenuous argument that, since no-load funds would not be sold through traditional sales channels but bought directly from Vanguard, they didn’t violate the board’s prohibition on distribution. Finally, at 1 a.m., the funds’ board voted 8–5 to eliminate all sales loads and reposition the Vanguard funds as no-load. This would make Vanguard a no-load distributor if investors would bring their business to Vanguard—if “pull” marketing would replace traditional “push” marketing and if the hoary maxim that mutual funds are not bought, they’re sold, could now be reversed.10

“Innovations in investment management were always for the sellers, not the buyers of investment services,” recalled Bogle. “I had always been close to our wholesaling sales force at Wellington. Each year, I’d say to them, ‘Tell me what you want—but you all have to agree—and I’ll work it out with Mr. Morgan.’ We knew our dealers felt that they had been let down so often that we really had nothing to lose by going no-load. We held a press conference at 10 a.m. Our 20 wholesalers all lost their jobs that day so they, and the 100 broker dealers they worked with most closely, were of course angry. Robert ‘Stretch’ Gardiner, the head of Reynolds & Co., made various threats, and Dreyfus ran full-page ads saying, ‘No load? No way!’ But in practical terms such as business lost, we felt no bumps at all when we went no-load. In a month, everything had quieted down.”11

After the directors’ decision to take over mutual fund distribution, some legal and regulatory issues remained. Vanguard’s plan required an exemption from the Investment Company Act, and that resulted in a shareholder’s request for a hearing. He did not want the Wellington Fund to pay any part of the cost of distributing other funds.12

There were broader issues requiring SEC approval. An administrative hearing on these issues—the longest such hearing ever held—began in January 1978 and lasted five weeks. Hearing Judge Max Regansteiner’s decision laid out the basis for Rule 12b-1, approved in May 1979, which for the first time allowed mutual fund complexes to add a new fee onto a fund’s management fee to be used to compensate brokers for not advising their customers to change from one mutual fund to another. Ironically, some called Bogle “the father of the 12b-1 fee,” an added fund cost that he spent much of his career railing against, and a fee that Vanguard has never charged.

Vanguard had filed a request with the SEC to allow it to spread the low cost of distribution across all its funds, instead of burdening a newly launched fund’s return by obliging it to absorb the entire cost of its own distribution when its assets were still small. In April 1981, the SEC decided mutual fund companies could use shareholders’ assets to help pay the costs of distribution, resolving the issue in the shareholder’s hearing. The SEC also affirmed Judge Regansteiner’s decision to allow Vanguard to allocate costs to the various funds, primarily in proportion to asset size. In another major break, Vanguard got permission to use the term “no load” in describing its offerings. The final 12b-1 rule required funds relying on 12b-1 not to call themselves no-load, another win for Vanguard.

The first Vanguard fund to go no-load in 1977 was the Warwick Municipal Bond Fund—a 6 percent load on a municipal bond fund had clearly been too much; muni funds normally returned much less than equity funds. A seminal change came with a law enabling mutual funds to pass through the tax exemption on municipal bonds to their investors.13 Bogle made two complementary moves. First, he cleverly structured the Vanguard municipals offering in three different maturities: short, medium, and long term. Investors could choose the maturity they wanted. This choice was well received. Second, the Warwick fund led the way in an important break away from Wellington. The fund directors, at Bogle’s persistent urging, decided to retain Citibank as the fund’s investment adviser, rather than Wellington Management. While the bank’s performance would, in a few years, lead to its termination as manager, the split expanded Vanguard’s independence from Wellington Management.

With interest rates over 10 percent and banks restricted by regulation to paying 5¼ percent on certificates of deposit, money market mutual funds were surging. Vanguard launched its Prime Money Market fund in 1975—four years after the first such fund, Reserve Fund, was launched—with Wellington Management managing the Prime Money Market portfolio. As Vanguard’s low fees became more widely known, its money fund’s assets surged.

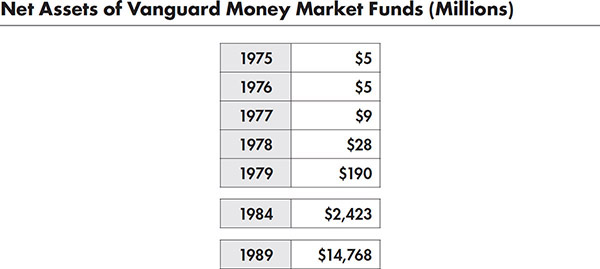

Though introduced as the simplest sort of investing, money market funds would become a surprising triumph at Vanguard. Confirming modest initial expectations, the money fund attracted only $5 million in 1976, largely from investors already using Vanguard. On this small base, the fund nearly doubled to $9 million in 1977. As rising inflation pushed interest rates higher on money market instruments, money poured out of low-paying bank certificates of deposit and into money funds invested in those higher-yielding instruments. Then interest rates exploded as Paul Volcker’s Federal Reserve fought to break up the even greater damage high inflation and expected further inflation were inflicting on the economy. As the table above shows, Vanguard’s money fund assets reached $28 million in 1978 and sextupled to $190 million in 1979. They then multiplied an astounding 12 times in five years, to $2.4 billion in 1984. The surge was not over. In the next five years, money market assets zoomed up to $14.8 billion in 1989 and became Vanguard’s largest product, nearly one-third of the assets at Vanguard.

In addition to the money market funds, Wellington Management had been managing 90 percent of Vanguard’s fixed-income fund assets. Jim Riepe and Jack Bogle agreed the time had come to bring all fixed-income investment management in-house. The case was easily made to the Vanguard board of directors: given the rapid growth in money market assets and in bond assets, both taxable and municipals, Vanguard could save investors significant money by managing these “plain vanilla” assets in-house and at cost—well below the conventional fees charged by Wellington Management and other managers.* Bogle argued that money market funds didn’t require investment management as traditionally defined. As fixed-income assets continued to increase, Vanguard’s cost advantage would grow rapidly.

Low fees became even more of a competitive advantage as Vanguard’s assets increased and its fees per thousand dollars decreased. Since money market funds all invested in much the same short-term instruments and since costs rose only slightly as assets ballooned, fees soon made a clearly visible, compelling difference in net returns. Investors increasingly turned to Vanguard. By 2022, Vanguard managed more than $250 billion in money market assets.

Bogle liked to say, “In investing, you get what you don’t pay for.”

Riepe agreed to recruit an experienced bond manager who could manage both money market funds and bond funds. He did not need to go far. He found his man in the fixed income department of Philadelphia’s Girard Bank: Ian A. MacKinnon, who was responsible for $3 billion in fixed income assets. When MacKinnon joined Vanguard late in 1981, he had to share an office with the auditors and work from a small desk with a wall phone nearby. He was soon joined by Robert F. Auwaerter, and together they organized a fixed-income management unit responsible for $1.7 billion in assets. MacKinnon’s unit would eventually manage $62 billion in 39 deliberately plain vanilla portfolios. In 1995, Vanguard was second only to Fidelity in total assets managed, with $180 billion. It was increasing its assets twice as fast as major competitors and was serving 3 million shareholder accounts and adding 3,000 new accounts every day. Wellington Management continued to manage Vanguard’s high-yield bonds and mortgage-backed securities, as well as preferred stocks—categories that demanded more research.

In marketing, Vanguard’s compelling competitive advantage was low fees. “In bond and money market funds, Vanguard’s expense ratios are anywhere from 50 to 100 basis points lower than our competitors’ fees,” MacKinnon noted. “Let me tell you, there’s no better way to start your investment day than with a 0.5 percent to 1 percent head start. There’s no need to sacrifice quality or strategy to boost yield.”14

As assets rose, Vanguard’s costs rose only slightly, so over time the cost of management per dollar invested went down and down again—eventually to just one basis point (one-hundredth of 1 percent) for some money and bond funds, dramatically lower than the competition. Among equity fund investors, higher fees were often somewhat perversely seen as indicative of more capable management and higher returns to come. Money fund investors would not ignore Vanguard’s lower fees. The powerful virtuous cycle accelerated. As Vanguard kept adding assets, its fees kept declining, attracting even more assets.

Sophisticated investors told their friends to try Vanguard. Many investors feel the relationship they have with investment organizations is remarkably significant; once investors have an established relationship, they tend to do more business with that same organization. Investors attracted by low fees to Vanguard’s money funds would often expand that relationship to include long-term bond funds, which also had low fees. And, if bonds, why not equities?

Once again, Vanguard was lucky. As the stock market turned in the early 1980s, what would become the best and longest bull market in US history began to gather momentum. John Neff’s Windsor Fund, by then distributed exclusively by Vanguard, produced clearly superior results year after year, and his many fans working on Wall Street invested their own money in Neff’s fund and told others what they were doing and why. (See Chapter 7.)

Meanwhile, Wellington Management was still getting battered. It remained investment manager for 11 Vanguard mutual funds and still had the institutional investment business of TDP&L, the Bostonians. But assets were down, and profits even more so. Worse, the collegiality that had been so central to the Bostonians had been severely shaken by their negative experiences.

Time and again Bogle did exhaustive homework to build a convincing case that reducing fees paid to Wellington was the one best answer to whatever he had identified as the problem this time, making it hard for his directors to persist in disagreeing with him. As Bogle took away one part after another of Wellington’s business, he was seriously threatening Wellington and his one-time “merger made in heaven.” As a public company, Wellington’s future rate of earnings growth was essential to its market valuation. But in building up Vanguard, Bogle was depriving Wellington Management of important business and profits.

Meanwhile the stock market was still way down from its peak, depressing Wellington’s investment management income from fees based on assets. As investors lost confidence in Wellington’s future earning power, its share price fell, and then fell again. The stock would actually drop almost 90 percent from a high of nearly $50 to a low of nearly $5. For the Bostonians, who had sold their company for stock, the price plunge was personally painful. They all realized it could get even worse. “It was just awful,” Doran would later observe. “We were fighting to retain everything we had, and Bogle was fighting to take it away. Our assets were shrinking while revenues and our stock price were declining.”

Without growth, it would be hard for Wellington to attract the new talent that every investment organization needs. If investment performance were ever subpar for two or three years, as often happens for even the best active managers, an easy case for termination of the Wellington-TDP&L merger could be made. It would link disappointment in investment performance with the disruption in Wellington Management’s economics and the obvious weakness in its organizational structure revealed by Bogle’s serial fee negotiations. If a few major institutional clients left—and their contracts all had “90-day notice of termination” clauses, making exit relatively simple—the impact would be hard to endure. If more than a few left, it could become a stampede.

Bob Doran, with help from others and several drafts, produced an internal memo titled “Looking Ahead” about the organizational values and culture he envisioned for Wellington. If it had come from almost anyone else, it might have been dismissed as just platitudes, but his partners knew from experience that Doran cared deeply, so they paid attention. As years had passed, those core values—mutual respect, pursuit of professional and business excellence, and providing opportunities for people to develop skills—were patiently nurtured into a compelling cultural reality for the Wellington organization.

Despite the acrimony between Bogle and his Wellington adversaries, individual friendships between some senior executives of Wellington and their former colleagues now at Vanguard continued and would, when opportunity came, facilitate rebuilding the working relationship between the two firms. (See Chapter 12.)

At Vanguard, Bogle and Riepe had achieved their ultimate strategic objective: an integrated, self-sufficient investment management organization that was now in control of distribution, client services, and investment management. Vanguard, to use its favored nautical terminology, was free to develop and implement a “blue water” strategy, full steam ahead.

Bogle enjoyed opening Vanguard’s annual management retreat with surprise announcements to spur innovation. In 1992, his theme was the firm’s “sacred cows.” Of a dozen that he believed others thought were inviolate, he focused on three that he wanted to challenge:

• Vanguard would not be a technology leader.

• Vanguard would not provide custom-tailored investment advice on asset allocation.

• Vanguard would not need to match the fee waivers some competitors offered large new customers.

While he had just recently told Forbes, “Technology is too expensive; we can’t afford to be the technology leader,” he now declared, “We can’t afford not to be technology leaders, so with our asset base growing by tens of billions, we are going to be the leader.” But this didn’t happen while he was CEO.

Bogle had grave doubts about Vanguard or any other firm being able to select active managers who could outperform the indexes, but with index funds gaining acceptance and asset allocation increasingly the focus of investment advice, he had now become convinced that offering advice could work. Again, however, Vanguard would not start giving advice until 1996, after Bogle’s departure.

For what he liked to call a shot across the bow of competitors, Bogle announced that Vanguard would offer those investing $50,000 or more in Vanguard’s four different US Treasury securities funds an expense ratio of only 0.10 percent, a price reduction of more than half. As Vanguard’s record-keeping technology advanced, beginning in 2000—eight years after Bogle’s first “shot across the bow”—Vanguard began gradually adding reduced Admiral pricing for more funds, and with lower minimum investments. Years later, Admiral shares had an average asset-weighted average expense ratio of 0.11 percent. This was half the Vanguard average and 80 percent lower than the 0.63 percent ratio of competitors. With these reductions, investors increasingly took notice and moved to Vanguard.

* The first institutional index funds had been offered as separate accounts by Wells Fargo Advisors (a subsidiary of Wells Fargo Bank), State Street Bank, and American National Bank, and all three were gradually signing up pension funds.

* Disputes between Bogle and Wellington Management were not limited to investment management fees. Another was over the “Valley Forge” building. Bogle wanted a long-term lease that would have obligated Wellington Management to keep a significant percentage of its assets tied up in the building. After extensive negotiations, a five-year lease was accepted.