CAHPTER 17

ADVICE

As CEO, providing investment advice is Tim Buckley’s top innovation priority. Vanguard is devoting major resources, financial and creative, to developing new ways advanced technology can be used to deliver custom-tailored advice to its investors. And none too soon.

Realistically, Vanguard has been late, as have most other investment firms, to recognize the importance of good advice in the overall experience of investors. Part of this lateness is due to the firm’s history. In its early “if you build it, they will come” years, Vanguard depended on do-it-yourself retail investors attracted by unusually low fees. Investment advice is personal to each individual, so it has traditionally been labor intensive, with high-cost labor, and did not scale. So advice as a service was understandably slow in developing.

While committed to good service, the majority of Vanguard’s clients are of moderate means, and the type of service they expect to pay for can be noticeably simpler than the top-end, individualized services of some competitors. As an example, for family offices of wealthy clients, Fidelity may provide a direct 800 number to a dedicated contact person and, more important, has people skilled at solving adjacent problems like what can be done to get better or less costly coverage in health insurance. It can bundle together requests from like-minded family offices to get lower costs or better service.

As a first small step toward offering advice, in 1993 Vanguard offered a PC-based software package to assist investors with retirement planning. A year later it introduced LifeStrategy Funds, four funds-of-funds offering prepackaged asset allocation suitable for four general risk levels: income, conservative growth, moderate growth, and growth. However, these “one size fits all” funds necessarily ignored the many ways people differed in such factors as wealth, life expectancy, and specific attitudes toward market risk.

Neither Jack Bogle nor Jack Brennan could find a way to make personalized advice cost-effective for investors or for Vanguard. This has been changing with advancements in information technology, bringing increasing focus by Bill McNabb on providing advice and even greater emphasis by Tim Buckley. Looking back, Brennan wishes he had been bolder sooner.

Providing advice on what each investor should do is, as Warren Buffett once said about investing, “simple, but not easy.” First, clarify each investor’s realistic goals in order of priority. Even quantitative goals like “enough for retirement” are obviously hard to specify unambiguously. Qualitative objectives like “more risk” or “less risk” are enormously difficult to quantify, and hard numbers have wide plus-or-minus boundaries. Second, specify the time available to achieve each goal. The combination of these two steps helps clarify what actions—particularly saving—will be needed each year to achieve goals. That’s the “simple” part. Then comes the “not easy” part: helping the investor actually do the saving and stay on plan, even as the market behaves in its curiously disconcerting, distractive, provocative ways.

For most workers, the move from traditional defined benefit pension plans to 401(k) plans shifted decision responsibility from full-time experts at corporate headquarters to the individual, who usually doesn’t have the time, expertise, or interest to master the complexities of investing. Many individuals also lack the detachment to make consistently rational decisions about long-term investments—usually “benign neglect” or “stay the course.” And most of the “advice” offered by most major financial firms is actually aimed at getting investors to buy services and products that are rather high cost, low value, or both—which, of course, is why they are hidden behind an “advice” wrapper.

Vanguard’s advice-embedded products, such as the LifeStrategy Funds and later Target Retirement Funds, helped clients choose a disciplined long-term investment program using low-cost, low-turnover, tax-efficient index funds and ETFs. Since most of us are not experts on investing, most of us would do better—usually much better—if we got and followed sensible advice from trustworthy investment professionals. (See “The Grim Realities of Investing.”)

The Grim Realities of Investing

In the sixties and seventies, “beating the market” became the dominant investor objective. In that very different stock market, active investing—stock picking—seemed the smart way to increase returns. Advice on long-term investment policy got sidelined. Sadly, most investors accepted the widely advertised possibilities of “outperformance” instead of the increasingly bleak, statistically low probabilities of achieving it. Moreover, as investors increasingly sought the better “performance” managers, fees rose—over time, more than doubling.

With fees and assets escalating from both new business and a generally rising market, income to management firms and their professional employees rose again. These larger financial rewards—along with the nonfinancial rewards of the always interesting work of active investing—attracted crowds of skillful competitors. Performance mutual funds, hedge funds, and other institutional investors with sophisticated computers drove any “less than the best” participants out of the business. Stock market activity has been transformed from less than 10 percent institutional trading to over 90 percent of trading by institutions. Almost all the professionals know almost all the same information at almost the same time, and they must buy from and sell to other experts; market prices quickly reflect almost all that is known by the experts. Most active managers are unable, after deducting management fees and costs of operations, to keep up with their chosen segment of the overall market. Not only have 89 percent of actively managed US funds fallen short of their chosen benchmark over 15 years, but identifying the outperforming 11 percent in advance is virtually impossible. Even worse, most of the past decade’s winners will become losers in the following decade.

Even optimists must recognize that what worked in the past is not working today. The change forces that brought about this adverse transformation are unlikely to reverse, and very unlikely to reverse by enough for long enough to make active investing a rewarding game again for clients.

As noted in Chapter 7, Vanguard’s main value-added in active investing is more important than doing better than the market: it helps protect clients from doing much worse. While usually outperforming most other active managers, even Vanguard’s experienced, skillful “manager of managers” group is not, on average, beating index benchmarks. The limited prospects for beat-the-market active management operations make sensible, personalized advice on investment planning stand out as the best way for investors to achieve investment success over the long run.

Vanguard has been increasingly successful with two different kinds of offerings:

• Products with embedded strategy, as pioneered by the LifeStrategy funds, with characteristics and purpose specified upfront. They are low cost and come in an array of easy-to-use forms so investors can confidently make reasonable selections for themselves.

• Services tailored to meet the particular objectives of each investor, given the investor’s assets, age, income, and other considerations.

From the start, the LifeStrategy Funds had low fees—one-third those of competitors—and allocated their investments differently. Compared to others, the Vanguard funds typically had over 10 percent more in equities at each stage of life and nearly 5 percent more in international stocks. The consequence of allocating more to equities was that those choosing Vanguard’s age-based product would likely find that they experienced slightly more fluctuations over the short term and more growth in value over the long term. Vanguard’s strong acceptance in the marketplace enabled it to catch up with competitors in age-based funds. Three years later, in 1997, it ranked third in assets so managed.

In 2003, Vanguard introduced Target Retirement Funds. These funds take as their target the year in which the investor will turn 65. Over the years, as the investor ages, the asset mix gradually shifts from equity index funds into bond index funds and cash. For example, for a 40-year-old investor, a fund might offer a portfolio of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, but for those age 50, the recommendation would be 50 percent in both stocks and bonds, and at age 70, a 70–30 bond-stock mix. Adhering to traditional allocations at these ages, the changes help offset the declining net present value of predictable future earned income as a person ages. In addition, since equity returns are “mean-reverting” (increasingly average), their long-term returns are less volatile and uncertain than their short-term returns.

These calculations don’t consider the impact of inflation on real returns nor the importance of other assets an individual might hold, such as a home or Social Security benefits or working past 65. (See Chapter 19.) Nor do they reflect the opportunity to educate plan participants about the nature of stock markets so they could be less nervous. Still, Target Retirement Funds make sense for most people and relieve participants of year-to-year managerial responsibilities they often do not want, such as rebalancing a portfolio’s asset mix as stock and bond market prices gyrate or staying on plan despite major market moves.

Target date funds (as commonly referred to in the industry) were introduced originally as a “default” investment option for 401(k) plan participants who were unsure how to invest their annual contributions. All too many 401(k) plan participants had been defaulting into a money market fund—okay for simple saving, not okay for long-term investment of retirement funds. While a generic “everyman” solution might not be just right for each investor, a well-known standardized solution that adjusted asset mix with aging was far better for most people than no plan at all.

Efforts to share the lower costs of serving larger investors can go astray. Target date funds are designed for investors with 401(k) or other tax-deferred accounts, but some investors hold them in taxable accounts. In 2021, Vanguard lowered the minimum investment for its lowest-fee target-date funds to $15 million from $100 million, and many institutions immediately moved their money to get the lower fees. This required the Vanguard funds for investors with more modest holdings to sell a lot of securities, saddling some taxable investors with large, unexpected tax bills. Some angry shareholders sensibly argued that Vanguard should have warned more effectively against holding these funds in taxable accounts. In a July 2022 settlement with Massachusetts securities regulators, Vanguard agreed to pay about $6 million, most of which will be restitution to eligible investors in that state.2

Vanguard entered the personal investment advisory and financial planning business in 1996. As Jack Brennan then said, “We are now able to serve the individual investors, retirement plan participants, and independent financial planners who have long been asking for assistance in preparing key components of personal investment plans.”

That offering, Vanguard Personal Advisory Service, featured a Vanguard investment counselor who would examine each client’s overall financial picture, including investment goals, spending needs, and risk tolerance. The counselor then determined the client’s asset allocation in up to 10 low-cost Vanguard funds. The ongoing investment advisory fee was set at a maximum of 0.50 percent annually, with tiered reductions for investors with more than $500,000 invested at Vanguard. Investment planning featured a one-time review of a client’s portfolio, along with asset allocation and fund recommendations. Retirement planning provided a detailed analysis of a client’s financial needs for retirement. Estate planning sought to maximize estate and gift tax deductions, among other strategies. Vanguard’s Personal Trust Services unit served as a fiduciary and provided professional assistance in establishing various types of trusts.

Brennan emphasized the low cost—“We are setting a new benchmark in cost efficiency for such services.” He emphasized that Vanguard did not intend to compete with full-service financial planners. “Our focus is on offering selected services conveniently—over the telephone—to our current shareholders in contrast with the face-to-face, full spectrum of services offered by traditional planners.”3

Vanguard continued to add advice offerings. In 1998, it introduced interactive retirement planning software for participants in its burgeoning 401(k) business. Three years later, it worked with Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe’s Financial Engines company, offering its online portfolio management service free to clients with assets of $100,000. Vanguard simplified its original advice offering in 2006 and called it Vanguard Financial Planning, or VFP. The service consisted of a 10- to 20-page plan developed by a Certified Financial Planner for investors with at least $100,000.

Subsequently the firm developed Vanguard Asset Management Services, which offered continuing wealth management and trust and estate planning. This service was designed for clients whose focus was shifting from building wealth to preserving it for the future. The adviser would help the client clarify goals and investment preferences. While this provided professional portfolio management with proven solutions and trustworthy, personalized service at low cost, it featured relatively high minimums and—by Vanguard’s standards—high fees. The minimum investable assets were $500,000 for individuals and $1 million for institutions. Annual fees were based on assets under management, with a minimum fee of $4,500.

In April 2015, Vanguard launched an investment advisory service combining traditional human contact with web-based advice and investment modeling algorithms under Karen Risi’s leadership.4 The service, Vanguard Personal Advisor Services, was limited to offering Vanguard products and emphasizes index funds and ETFs. The fee, only 0.3 percent of assets, is further reduced for accounts over $5 million. Vanguard recently increased its number of on-staff investment advisers in PAS from 300 to 1,000—all paid salary and bonus, rather than the usual commissions, which encourage trading—and invested $100 million to create a dynamic web interface.

“We wanted to bring our mission to an even broader audience,” Risi explained. “When we analyzed why we lost retail clients, we saw it was because they felt we did not provide enough advice. We decided it wasn’t enough to make our current advice offering better. We wanted to totally reinvent advice and we wanted to be disruptive. Sometimes the media misunderstands our Personal Advisor service. Some think we developed it in response to the new robo-advisers.* But that’s not true, not at all. PAS was on the drawing board years ago.”

She continued: “Technology enables us to give more advice to more people at lower and lower cost. That’s the flywheel effect. Some investors want to work with a coach on investing who can make them feel comfortable with what they’re doing as investors during life’s major transitions, such as getting married or buying a new home. Our investors also worry about retirement savings and rates of drawdown. . . . We wanted our offering to be extremely low cost. In setting the fee, our bogey was the industry average fee of 100 basis points. We ran some focus groups and found a willingness to pay 25 to 40 basis points. So, we focused on 30 basis points, less than a third of 1 percent, believing that if we were rigorous about customer segmentation and ran an efficient virtual experience, with the flywheel effect, we could make the economics work at that low price. Scale is the key to technology—and vice versa.”5

Competitors that offer the traditional method of advising and charge 100 to 120 basis points won’t be able to compete if investors are well informed about cost versus value. The traditional high-cost “labor” model, based on charm, individual trust and lots of services other than investment management, does not scale. Technology is the key to scalability, removing costs and allowing lower fees. Already, fees for advice are coming down.

With 6,500 crew members, including 1,000 Certified Financial Planners, Risi’s group potentially serves Vanguard’s 8 million individual investors outside 401(k) plans—a giant potential market for value-adding advice services. She has her focus on services and components of services that lend themselves to automation and the scale to absorb the capital costs and benefit from accelerating advances in technology, including artificial intelligence. Automation has been particularly productive in routine functions like enrolling new clients or transferring accounts into Vanguard from other organizations.

About two-thirds of the CFPs transferred in from other areas of Vanguard. The others are former Registered Investment Advisers who did not enjoy selling just to open new accounts, but do like working with investors to help determine their real long-term priorities and developing programs that enable them to accomplish those objectives.

Determining appropriate individualized advice is complex but can, Vanguard believes, be incorporated into the process without involving the investor in every detail—as a Swiss watch has lots of complexity inside but the user tells the time by a glance at the face. Advisers can walk individual investors step-by-step through their decisions and help them pull the trigger to take appropriate action. Relationships are built by being trustworthy over time, defining each client’s problems or opportunities, and designing the best solutions.

The main force driving the increase in demand for ETFs and index funds is not coming from individual investors, but instead from financial advisers who direct investors to them because of their low cost and ease of administration. In addition to serving existing Vanguard clients, Risi’s group works with outside advisers through three main channels: RIAs, regional securities firms like Edward Jones, and national organizations such as JPMorgan Chase.

Working with RIAs has grown into a major business channel for another Vanguard advice-oriented operation, Financial Advisor Services (FAS), headed by Vanguard veteran Tom Rampulla. FAS focuses on RIAs and other financial intermediaries with a national salesforce and helps them deliver cost-effective advice to individual investors with low-cost ETFs. The core of the concept is recognition that the old beat-the-market mission of an RIA has become increasingly difficult to achieve. The adviser is encouraged to focus less on actively managing portfolios—trying to outperform the markets—and more on relationship-oriented services such as financial planning, developing custom-tailored, long-term investment programs and “behavioral coaching”—coaching clients on best practices about how to stay with their customized investment plans.

The Advisor’s Alpha process, as FAS describes its techniques to help advisers add to clients’ returns, starts with developing an investment plan, with the obvious view that even a simple plan is better than no plan. “If you fail to plan, plan to fail” has become the kind of phrasing Vanguard uses to make its messaging easy to remember. In developing a plan with a client, the adviser gains vital information, making it easier for both to focus on the client’s major objectives.

Understanding the emotional drivers behind decisions is usually the key to understanding each client and to effective behavioral coaching. Vanguard’s focus is on “the headlines in clients’ lives, not the headlines in the financial news.” We all like coaches who focus on how we are getting better, and dislike being confronted with our mistakes. RIAs are encouraged to celebrate clients’ gains and improvements as they achieve more of their most important personal objectives with the help of the adviser as their behavioral coach.

Service is crucial in the competition for financial advisers’ business, because the products various firms offer are so similar. Vanguard has a dedicated website serving financial advisers, where it promotes the Advisor’s Alpha, showing specific ways an adviser can help clients increase returns by staying on plan through market gyrations to achieve long-term objectives such as children’s college tuition or retirement security. Vanguard research highlights business-getting opportunities, such as showing that 69 percent of investors with over $5 million do not have a financial plan.

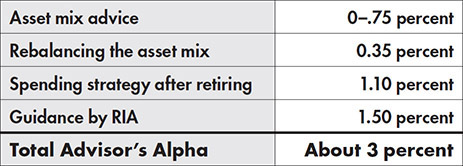

Vanguard tries to quantify Advisor’s Alpha—how much good advice may enhance returns. Though easy to debate in terms of exact amounts, which obviously vary by individual investor and from one market environment to another, the components and magnitudes of the Advisor’s Alpha that Vanguard emphasizes in this calculation seem credible—especially if you know how costly investors’ unadvised mistakes usually are. The estimated total added value of 3 percent a year is perhaps overly generous, but the assumptions generally fit investors’ experiences and actual costs.

Vanguard salespeople travel all over the United States serving over 1,000 financial advisory firms, which, in turn, serve investors with over $3 trillion in investments. Three components combine: technology, client expertise, and investment expertise. Because Vanguard’s ETFs and mutual funds are so low cost, that leaves more room for the financial advisers’ fees. As Vanguard continues to gain recognition among consumers, more advisers’ clients know about and feel comfortable with Vanguard, particularly when using its ETFs. Vanguard makes its technology tools readily available to financial advisers to label with their own firms’ names and use with their clients in new ways that increase their earnings.

Vanguard’s commitment to advice led in July 2021 to its first-ever acquisition. Just Invest, a small, new firm, helps RIAs design customized, “direct” index portfolios for individuals who want to tailor specific aspects of their portfolios, such as excluding gun manufacturers or oil stocks or emphasizing specific ESG (environmental, social, and governance) stocks. With fractional shares now available, and new technologies making it possible to automate customization at low or even no cost, managers can offer customization economically. In another application, tax loss harvesting, investors can offset taxable gains with sales of stocks that have taken losses. Demand for direct indexing is expected to boom; BlackRock acquired Aperio, a direct indexer, in late 2020 for $1.05 billion. While Vanguard made no commitment, the technology could be used to serve individual investors too.

The value-adding work of an RIA lies partly in developing a trust-based relationship with each investor and partly in figuring out the best solution to a complex personal problem. Solving the lifetime “money puzzle” of each investor is a labyrinthine, multivariate problem full of uncertain factors that influence each other in varying degrees, including the time available, the income and savings available, various future investment returns and various dates of retirement, the uncertain need for expensive health care or assisted living, the investor’s philanthropic hopes, the complexities of estimating future returns during retirement and determining an appropriate drawdown in retirement—and a variety of other needs or wishes that many investors have. Difficult for humans to process, such problems are simple for advanced algorithms to solve swiftly at low cost and with no human reluctance to rework the whole solution almost instantaneously at any time.

Given the size of this opportunity, Vanguard intends to be a leader in the development of algorithmic investment advice for the millions of individual investors and the many financial advisers with whom it has established trust-based relationships. Making advice the leading edge of its strategy epitomizes Vanguard’s drive to remain the investment management industry’s leader in serving individual investors under Tim Buckley as chief executive.

* Services that provide digital financial advice or management with minimal human intervention.