Chapter 8

Perfecting the Financial Ratios for Investment Banking

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Finding out how investment bankers use ratios to glean insights from financial statements

Finding out how investment bankers use ratios to glean insights from financial statements

![]() Uncovering how much companies are worth using valuation ratios

Uncovering how much companies are worth using valuation ratios

![]() Seeing how financially well positioned a company is with liquidity ratios

Seeing how financially well positioned a company is with liquidity ratios

![]() Stacking up companies against each other using profitability ratios

Stacking up companies against each other using profitability ratios

![]() Detecting how well management uses shareholder money with efficiency ratios

Detecting how well management uses shareholder money with efficiency ratios

![]() Tracking how quickly a company drives its bottom line with growth-rate analysis

Tracking how quickly a company drives its bottom line with growth-rate analysis

If you’re like most people, many ratios in your life provide insights about your daily routine. Your car’s miles-per-gallon is a ratio that tells you how efficient your car uses energy. And your effective tax rate indicates how much of your paycheck winds up in Uncle Sam’s hands.

Investment bankers, too, make extensive use of ratios to glean insights about companies and industries. Ratios are almost entirely calculated by extracting different pieces of data from the financial statements and comparing them with each other across time and with similar companies. It’s the process of comparing financial data that provides keys to insightful analysis.

In this chapter, we show you how investment bankers tear apart the financial statements and apply ratio analysis to see what’s really going on. You find out how richly a company’s stock is prized by investors using valuation multiples. You see which companies may need a big-time infusion of cash to stay afloat using the liquidity multiples. You see how to size up a company’s money-making potential using profitability ratios. You also understand how well the management team is putting shareholders’ money to work using the efficiency ratios. Plus, understanding a company’s growth prospects is also a use of ratio analysis.

The financial statements are useful, but ratio analysis makes them invaluable. In this chapter, you find out how to get ratios to work for you.

Valuation Multiples: Assessing How Much the Company Is Worth

The top question investors ask is how much a company is worth. Putting a price tag on a company using its financial statements is a full-time occupation of many of the world’s most-famous investors. But as is often the case for investment bankers, what’s even more important than what a company is actually worth is how much other investors say it’s worth. The famous economist John Maynard Keynes made the analogy to picking the winner of a beauty contest. The goal isn’t to identify the most beautiful person, but to identify the person the most judges think is the most beautiful. Alas, the market is a fickle judge of beauty.

Many of the financial products and offerings investment bankers sell are based on the market valuation of a company, or the price investors place on an entire firm. Market valuation can rise and fall over the years as investors’ attitudes about a company ebbs and flows. And it’s exactly these changes in investors’ appetites for a company and its securities that investment bankers must closely monitor. Timing can be critical when selling investment securities, and investment bankers want to sell when the demand for the securities is strong.

Investors’ favorite valuation tool: P/E ratio

If there’s a famous valuation ratio, it’s the price-to-earnings or P/E ratio. Even regular individual investors are often familiar with P/E ratios, and they use them as a guide to indicate when a stock is richly valued or arguably undervalued. The P/E ratio at its essence is a simple division problem:

The P/E ratio tells investment bankers how much investors are willing to pay for a claim to a dollar of a company’s earnings. The higher the P/E ratio, the more richly valued a company and its stock are.

Investment bankers often want to look at P/E in a purer form that’s based on hard numbers from the financial statements. For that reason, it’s common for investment bankers to zero in on P/E based on historical earnings minus any extraordinary items. That means investment bankers divide the stock’s current price by a company’s diluted earnings per share excluding one-time items (such as restructurings, divestitures, and any other non-recurring items). A company’s diluted earnings per share excluding one-time items is often calculated as follows:

- Diluted Earnings per Share Excluding One-Time Items = (Total Revenue – Cost of Revenue – Operating Expenses + Interest Expense – Income Tax Expense – Preferred Dividend + Unusual Items) ÷ Diluted Shares Outstanding

Going old school with price-to-book

Price-to-earnings is a popular measure, but an imperfect one. The P/E ratio can tell investment bankers what investors are willing to pay for a dollar of earnings. A company’s earnings, while important, are just one dimension of its value. Another measure, one that’s closely watched by investors who are looking for bargains and investment bankers alike, is book value.

Book value is the corporate equivalent of a person’s net worth. Investment bankers often focus on tangible book value, because it strips out assets that may be hard to accurately value or quickly sell. A company’s tangible book value is its tangible assets minus its liabilities. The price-to-book ratio is the company’s stock price divided by book value. The ratio tells investment bankers how much investors are paying for every dollar the company would raise if it were, in theory, liquidated and book value could be realized for the assets and liabilities.

In some situations, the price-to-book is preferable to P/E:

- When dealing with a young company: When companies are just starting out, they may have diminutive levels of earnings or even losses. In cases like these, the P/E ratio may be ridiculously high or not even meaningful.

- When a cyclical company is in a downturn: Earnings of some companies rise and fall by large degrees along with the ups and downs of the economy. During periods of economic decline, a company’s P/E may look artificially high if the stock price hasn’t fallen by as much as earnings. This can give a misleading impression of valuation.

- When dealing with a capital-intensive business: In some industries, massive investments in plant, property, and equipment are required. These firms may make enormous investments that are more significant to the value of the company.

Putting a price on profitability

Even if you’re not an investment banker, you probably have heard of P/E ratios and price-to-book. Investment bankers are drawn to strange-sounding words and acronyms, especially to get a better handle on valuation. Enterprise value to EBITDA is certainly a ratio that’s a bit off the beaten path. But it’s designed to give investment bankers a more accurate read on how richly the market values a company by making a number of arcane, but reasonable adjustments. These adjustments can give investment bankers a way to compare how richly different companies are valued, even if these companies are carrying different amounts of debt. The enterprise value/EBITDA ratio is often used along with the P/E by investment bankers to see how pricey a company is.

Market value is certainly the most common way for investors to gauge how much a company is worth. Market value is the company’s stock price multiplied by its number of shares outstanding.

But market value, while objective, has its shortcomings when it comes to measuring the value of a company. A company’s market value is a reflection of the value of the company’s stock. Stock investors, in theory, give a company’s value a haircut to reflect the debt the company is carrying. This valuation haircut makes total sense for stock investors, but not so much for investment bankers who need to know how much the entire company, not just its stock, is worth.

To make the market value statistic fit their needs, investment bankers often use enterprise value, which is the market value of a company with its net debt added back.

Enterprise Value = Market Value – Cash and Short-Term Investments + Total Debt

You’re now halfway to understanding the enterprise-value to EBITDA ratio.

Another acronym you’re practically guaranteed to hear if you hang out with investment bankers long enough is EBITDA. EBITDA is short for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. The EBITDA measure is investment bankers’ answer to the widely accepted but flawed measure of corporate earnings called net income. EBITDA involves a series of adjustments to net income to get to a measure of profitability that’s not distorted by accounting or financial maneuvers.

EBITDA is calculated as follows:

EBITDA = Net Income + Tax + Interest + Depreciation and Amortization

Now that you’re a master of enterprise value and EBITDA, the trick is to bring them together. Dividing enterprise value by EBITDA tells investment bankers the total value placed on a dollar of the company’s earnings adjusted items that don’t cost cash, like depreciation and amortization.

EBIT = Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold – Operating Expenses – Depreciation – Amortization

Some investment bankers loosely interchange EBITDA with cash flow from operations, but that’s not completely accurate. EBITDA and cash flow from operations involve different calculations. (If you want to understand what cash flow from operations is, there’s a full explanation in Chapter 7.)

Liquidity Multiples: Checking Companies’ Staying Power

No matter what kind of shape a company is in, investment bankers can usually find a financial product to offer the management. Investment bankers are a particularly creative and innovative bunch. When a company is growing and in need of cash to expand or grow, the investment bankers’ ability to sell securities is very valuable.

But when a company is running into trouble, and needs creative ways to stay afloat, the investment banker is again tapped to help line up investors willing to inject much needed cash into the company.

Investment bankers can use liquidity ratios in a number of ways to gauge what kind of financial shape a company is in or to tailor the products and services pitched to the company. Here are some ways an investment banker might use the liquidity ratios to understand a company’s health:

- To size up how much of a company’s financial resources are tied up in debt: Companies can raise money in a variety of ways, with offering stock and selling debt being among the most common. The financial ratios help investment bankers see how reliant companies are on debt financing versus equity, or stock, financing. Here’s where the debt-to-equity ratio comes in handy.

- To determine whether a company can keep its head above water financially: Many companies can afford all their bills, including those from their investment bankers, as long as the business is humming along. But it’s important for investment bankers to understand what would happen if the business suffered a hiccup. Would the company’s stumble be enough to make it unable to pay its upcoming bills? The quick ratio was designed to handle this question.

- To see how much of a bite borrowing takes from profits: A company can turbo-charge its profits by using all sorts of borrowed money. But the question is whether the business is able to justify that level of borrowing or leverage. Additionally, investment bankers need to know how much larger a company’s profit is than interest payments, which is measured by the interest coverage ratio.

Deciphering debt to equity

Companies usually have a number of ways to raise money. And choosing between their chief options — issuing debt or stock — can have a profound influence on the company. For instance, companies that load up on debt can give their profit a real jolt when things go well because they’re able to invest the money into moneymaking assets. But debt comes with a cost (interest), and if the cost of borrowing outstrips the returns, the company is actually destroying value.

Investment bankers, too, must understand the mix of a company’s financing sources to tailor the products they sell. For instance, if a company is already getting a big portion of its financing from debt, then it may be a tough sell to talk the company into another debt offering.

Calculating a company’s debt-to-equity ratio is pretty straightforward. It’s simply the company’s total liabilities divided by shareholder’s equity. Both of these items are readily available from a company’s balance sheet, as described in more detail in Chapter 7.

It’s true that the higher the ratio, the more the company relies on debt financing. Some industries are more stable, though, and can comfortably handle more debt than others can. Industries that require large investment in equipment and those with stable cash flow — like electric utilities — tend to handle higher debt-to-equity ratios than those with less investment required, like software firms. It’s important to consider debt-to-equity along with interest coverage, which you’ll read about shortly. You can see how widely debt-to-equity ratios can vary by different industries using large companies as an example in Table 8-1.

TABLE 8-1 Debt-to-Equity Ratios by Industry

|

Industry (Company) |

Debt-to-Equity Ratio |

|

Integrated oil and gas (Exxon Mobil) |

25.5% |

|

Industrial conglomerates (General Electric) |

195.7% |

|

Systems software (Microsoft) |

80.7% |

|

Pharmaceuticals (Merck) |

99.5% |

|

Electric utilities (Southern) |

146.9% |

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence as of June 30, 2019

Getting up to speed with the quick ratio

Quick! Could you pay off your bills if your income suddenly went to zero? It’s a harrowing thought, but that’s the kind of thinking investment bankers must sometimes apply to companies. Knowing how to stress-test a company and knowing what would result if the unexpected happened is what the quick ratio does. The higher the quick ratio, the more the company has in liquid assets (assets that can readily been turned into cash) that could be used to pay upcoming bills. The ratio is calculated as follows:

Interpreting interest coverage

There are several places where more coverage is better, and that certainly goes for Speedo bathing suits. More coverage is also good for companies when it comes to making interest payments.

When companies take on debt, they’re assuming liability for the resulting interest and principal payments. These payments aren’t negotiable and companies don’t have the right to pay them when they feel like it. Interest is due and must be paid or bad things happen, including wiping out the common shareholders if things degenerate enough. The city of Detroit discovered that in mid-2013 and Sears in 2018.

Investment bankers must understand not only how much debt a company has relative to stock, using the debt-to-equity ratio described earlier, but also how onerous the interest payments are with respect to operating earnings. Interest coverage is a catchall term for a number of ratios designed to help investment bankers measure the significance of interest payments.

With investment bankers, a top interest coverage ratio is EBIT/interest expense, which is calculated by dividing a company’s earnings before interest and taxes by the interest expense. The higher a company’s interest coverage ratio, the more it’s able to afford its interest payments.

Profitability Ratios: Seeing How a Company’s Bottom Line Measures Up

Beginners in investment banking commonly refer to a company as having “high margins.” That kind of clichéd talk may sound impressive in a locker room, but it sounds quite naïve in a boardroom.

As more experienced investment banking professionals know, the term profit margin doesn’t really mean much. Profit margin is a catchall term that describes a number of financial ratios that are designed to help put a company’s profitability into perspective. The key ways to measure margins include gross margin, income from continuing operations margin, and net margin.

But the income statement gets even more interesting after its data is applied to ratios. Financial ratios just put different parts of the income statement into perspective to provide additional insights not seen by looking at absolute numbers.

There are countless ways for investment bankers to slice and dice the financial statements, and there are countless financial ratios. But in this section, we fill you in on several of the ratios that matter most or that come up most frequently in investment banking transactions.

Why gross margin isn’t so gross after all

If you knew a company turned a gross profit of $3 billion, that piece of information by itself wouldn’t tell you much. If you read Chapter 7, you know that gross profit is what’s left of revenue after paying direct costs. But $3 billion in isolation isn’t very telling. Enter gross margin. Gross margin is a relatively simple calculation that tells investment bankers a great deal about the business.

A company’s gross margin is gross profit divided by total revenue. The product tells you how much of every $1 in revenue the company keeps after paying direct costs. In essence, this is the money that’s left and can be used to pay overhead and provide a return to shareholders.

Income from continuing operations: Looking at profit with a keen eye

A company’s gross margin may tell you how a company is doing managing its revenue and raw materials costs, but there’s much more to running a business profitably.

Investment bankers pay attention to income from continuing operations margin as a way to see what proportion of revenue the company is able to hang onto after paying all its costs, including overhead, before the distortion of interest expenses and other peripheral costs. The ratio disregards unusual or one-time items that don’t have anything to do with the ongoing functioning of the business, such as asset sales or restructuring charges.

Income from continuing operations margin is calculated as follows:

Income from Continuing Operations Margin = (Total Revenue – Cost of Revenue – Operating Expenses + Net Interest Expense + Unusual Items – Income Tax Expense) ÷ Total Revenue

The result will be a percentage that tells you how much of every dollar the company keeps from revenue after paying all the ongoing costs of doing business.

Keying into profits with net margin

Net income isn’t perfect. After all, net income is a financial measure created by accountants for everyone, not a tool designed for investment banking professionals. Even so, and despite the criticism mounted on net income, it’s still a basis of accounting that all companies must follow. The uniformity of net income makes it a valuable tool, if anything, to compare disparate companies with each other.

Another beauty of net margin, despite its shortcomings, is that it’s easy to calculate. Net income is provided by companies on their income statements. Calculating net margin is just a matter of:

This calculation of net margin gives you a percentage that tells you how much of every dollar a company earns after paying all its expenses, at least following the sometimes-convoluted rules of accountants.

TABLE 8-2 Net Margin by Industry

|

Industry (Company) |

Net Margin (Five-Year Average) |

|

Energy (Exxon Mobil) |

7.0% |

|

Technology (Microsoft) |

21.6% |

|

Healthcare (Merck) |

14.0% |

|

Industrials (Boeing) |

7.2% |

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence through 2018

Efficiency Ratios: Knowing How Well the Company Is Using Investors’ Money

O.P.P. may be best known as being “other people’s property,” or even the 1991 hit rap song from Naughty by Nature. But it’s an apt description of the way companies are structured and financed.

Most large public companies are not owned by the CEO or the management team. Large public companies are run using other people’s property, specifically stocks and bonds.

But investors don’t entrust money to management lightly and they’re not doing it for fun. Investors are looking to get a return on their invested capital and pay close attention to whether management is delivering adequate returns.

Efficiency ratios can be a very useful way for investors to monitor whether a company’s management team is putting money entrusted to it to good use. CEOs like to talk a big game and say they’re positioning the company well for the future. But the efficiency ratios cut beyond the hot air, something investment bankers must be well prepared to address. Efficiency ratios not only show if the management is a proper steward to the financial resources entrusted to them, but by how much.

The primary efficiency ratios of most importance to investment bankers include

- Return on assets: Is that fancy factory the company borrowed money to buy really paying off for investors? Find out using return on assets. Return on assets tells the investment banker how much of a profit is being driven from the company’s fixed investments, such as plant, property, and equipment.

- Return on capital: Companies may sell stock and they may issue debt. Raising money puts cash into the hands of the management team, which then, presumably, invests that cash in projects that generate returns. But are the returns the management is getting enough to justify the cost of the money they raised? That’s the question investment bankers can answer using return on capital.

- Return on equity: If there’s anyone who focuses on what kind of return they’re getting, it’s the shareholders. After all, the bondholders know what they’re getting. As long as the company stays in business, and pays its debts, bondholders can collect both the coupon rate (the interest rate the borrower agreed to pay during the life of the loan) paid on the bonds the company issued and get the principal amount of the loan back. But stockholders don’t receive a payment as certain or concrete as an interest payment. That’s where return on equity comes in. This handy ratio can tell stock investors what kind of return the company is generating on the money entrusted to it.

Finding out about return on assets

When investors buy stock or debt issued by a company, they’re taking a leap of faith. The assumption is that the company is going to use the money to buy assets that can be used to drive higher profits, which can be paid to shareholders. But the type of assets bought can have a big influence on the returns shareholders ultimately get.

Let’s say a company needs to buy a fleet of cars for salespeople to deliver product. That’s reasonable. The company could do the prudent thing and buy moderately priced Ford vans. But a company may instead decide that it would be a heck of a lot more fun if the salespeople were cruising around in brand-new Ferrari sports cars. True, that would be more fun, but it would wreak havoc on the company’s return on assets (ROA).

Poor investments that don’t deliver the return are what investment bankers are looking for with the ROA calculation. The measure is calculated as:

You already know how to get the company’s net income, to plug into the numerator. To get the denominator, the average total assets, you’ll have do to a bit of work. Add the value of the company’s assets at the end of the period you’re analyzing to the value of the assets at the beginning of the period and divide by 2.

Investment bankers know that the higher the ROA, the better the company is harvesting profit from the assets it has acquired and deployed. Imagine that the company with the fleet of vehicles hauls in $10 million in net income. Now, the company using the low-cost Ford vehicles has assets of $100 million. That company’s ROA is 10 percent. But if the company instead opts for the Ferrari fleet, and has assets of $500 million, suddenly the ROA drops to a paltry 2 percent.

Digging into return on capital

Return on capital (ROC) is an extremely important financial ratio to investment bankers. It shows investors how much of a profit the company is hauling in from the level of capital — both debt and equity — plowed into the company. Again, if a company has access to boundless capital, it wouldn’t be surprising that the company would generate lofty returns. ROC is a ratio that attempts to quantify how skilled the management is at putting the money — both debt and equity — entrusted to it to work.

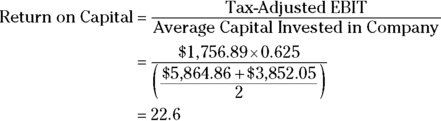

Calculating ROC takes a bit of work. The formula, in a simplified form, looks like this:

Looks easy, right? The trouble is, it takes a couple of additional steps to derive the numerator, tax-adjusted EBIT, as well as the denominator, average capital invested in the company.

First, to get tax-adjusted EBIT, there is a shortcut: You’ll start with EBIT (see “Putting a price on profitability,” earlier in this chapter). You could go to all sorts of trouble adjusting EBIT for taxes, but a simple workaround used by many investment bankers is to simply multiply EBIT by 0.625. This will take EBIT down by the appropriate corporate tax rate of 37.5 percent.

Now, it’s time to get average capital invested in the company. Average capital invested in the company is a tally of all the debt and equity invested in the company. Because it’s an average, it’s generally advisable to take the capital invested in the company during the most recent 12-month period, add the capital invested in the company during the previous 12-month period, and then divide the sum by 2.

If your head is spinning on this one, don’t fret. Table 8-3 has all the information you’d need to calculate Hershey’s return on capital.

In Table 8-3, believe it or not, you have more than enough to calculate return on capital. Using the formula from earlier, you calculate return on capital as follows:

TABLE 8-3 Calculating Hershey’s Return on Capital

|

Financial Measure |

2018 ($ millions) |

2017 ($ millions) |

|

EBIT |

1,756.89 |

Not needed for calculation |

|

Total equity |

1,398.72 |

915.34 |

|

Minority interest (debt) |

8.55 |

16.23 |

|

Short-term borrowings (debt) |

1,197.93 |

599.36 |

|

Current portion of long-term debt |

5.39 |

300.10 |

|

Long-term debt |

3,254.28 |

2,061.02 |

|

Total capital |

5,864.86 |

3,852.05 |

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence

This tells you that Hershey generated a 22.6 percent return from the assets invested in it. Not too shabby.

Uncovering company secrets with return on equity

Stockholders think bond investors are a boring lot. And bond investors think that stock investors are wild-eyed dreamers with no respect for the dangers of investment risks. Given the often acrimonious relationship between stock investors and bond investors, it’s not surprising they would keep their interests separated in the financial ratios.

Stock investors don’t get too concerned about whether bond investors are getting their due, as long as they’re getting theirs. The return on equity (ROE) ratio is a way to see how well management is making use of the money invested in the business by the shareholders. Return on equity is calculated using data obtained from both the income statement and the balance sheet, as follows:

Calculating a company’s growth rate

Investment bankers know full well that financial statements are largely a look back at a company’s past. A company’s most recent balance sheet, for instance, tells you what the company owned and owed at the point in time at which the statement was produced. The criticism of financial statements is that they’re ancient history by the time they’re released in this world of hyperactive trading.

Just looking at static financial statements can be a bit limited when it comes to seeing financial trends. Using trends, an investment banker may be able to intelligently speculate in which direction a company may be headed. Think of financial trends as the investment banker’s crystal ball. The crystal ball may be a bit cloudy, but it does provide a sense of the trends.

This formula can be applied to just about any two numbers you’ll find on the financial statements to spot trends. In Table 8-4, you see an example of calculating growth rates for various measures of Hershey.

TABLE 8-4 Hershey’s Growth Trends

|

Financial Measure |

2018 ($ millions) |

2017 ($ millions) |

Growth Rate |

|

Revenue |

$7,791.1 |

$7,515.4 |

3.7% |

|

Cost of goods sold |

$4,198.2 |

$4,054.9 |

3.5% |

|

Selling, marketing, and administrative costs |

$1,797.4 |

$1,866.1 |

–3.7% |

|

Interest expense |

–$146.9 |

–$100.1 |

46.8% |

|

Net income |

$1,177.6 |

$783.0 |

50.4% |

Looking at Hershey’s growth rates gives investment bankers an entirely different perspective on the company’s financials. With Hershey, you can see that the company is growing slowly with just low single-digit percentage revenue growth from the chocolate business. The company is also keeping a good relative control on its raw materials costs, shown by the modest 3.5 percent increase in cost of goods sold.

But the growth analysis of Hershey pinpoints a potentially troubling 47 percent increase in interest expense. Many companies boosted leverage, or the amount of borrowing, in the late 2010s. Interest rates were low and encouraged debt. This piece of information can drive the investment banker back to the 10-K to get more answers.

It turns out that Hershey’s interest expense jumped in 2018 due to borrowing money to buy Amplify Snack Brands. Amplify makes “better-for-you” snacks like SkinnyPop popcorn. The company also faced higher interest rates on some of its loans. It also took on $1.2 billion in additional borrowing in May 2018.

This is critical information for investment bankers to know. Bankers must be sensitive to the fact that Hershey management is certainly eyeing the rising interest expense before approaching it with a deal, especially another merger opportunity. That’s especially true since the company is still digesting its last big buyout.

Valuation multiples can be invaluable tools in helping investment bankers gauge when demand for a company’s stock or debt may be strong. Watching the trend in these ratios can help make an offering more successful for the sellers of the securities, the company.

Valuation multiples can be invaluable tools in helping investment bankers gauge when demand for a company’s stock or debt may be strong. Watching the trend in these ratios can help make an offering more successful for the sellers of the securities, the company. At its heart, the P/E ratio is simple, but it can quickly get complicated as you dig deeper. The numerator of the ratio, the stock price, is something everyone can agree on. Investment bankers can obtain the stock price from any quote service. But the denominator, a company’s earnings, is subject to debate. Individual investors often look at forward P/E ratios, which are the stock price divided by how much the company is expected to earn over the next year. But investment bankers tend to look at things a bit differently.

At its heart, the P/E ratio is simple, but it can quickly get complicated as you dig deeper. The numerator of the ratio, the stock price, is something everyone can agree on. Investment bankers can obtain the stock price from any quote service. But the denominator, a company’s earnings, is subject to debate. Individual investors often look at forward P/E ratios, which are the stock price divided by how much the company is expected to earn over the next year. But investment bankers tend to look at things a bit differently. Notice that the quick ratio excludes inventory. While inventory is an asset that can be sold, it often takes time to sell and the amount received can be unpredictable, so it’s excluded from the quick ratio.

Notice that the quick ratio excludes inventory. While inventory is an asset that can be sold, it often takes time to sell and the amount received can be unpredictable, so it’s excluded from the quick ratio.