CHAPTER 4

The Security Process Management Framework

In the preceding three chapters I explored the case for IT security metrics and provided advice for choosing and designing effective measurement strategies and addressing the data requirements of those strategies. At this point, you should have a good idea of how to methodically select the security metrics you may be interested in exploring. But I have not yet discussed the larger context of these metrics beyond the idea that goals are important to measuring security, as illustrated in the Goal-Question-Metric (GQM) method described in Chapter 2.

Metrics are not nearly as effective when taken out of context, analyzed in piecemeal fashion, or undertaken as stand-alone exercises. The real power and value of metrics emerge when they are considered as part of a larger and ongoing programmatic approach to security that views IT security as a true business process and not simply an exercise in controls or technology. The Security Process Management (SPM) Framework that I propose in this chapter is designed to help you to look at your security metrics program in just this way.

Managing Security as a Business Process

In some ways, IT security challenges today mirror the challenges faced by IT a decade or more ago. Security skills and techniques have become more prominent, but they are still fairly esoteric. Security professionals are often seen as eccentric and paranoid, with special abilities that are less well understood than mainstream IT pros. In the old days, IT was staffed by the oddball techies in the backrooms of the corporation, hidden from view and poorly understood. Today the security experts have seemingly mystical knowledge on which the now-common IT infrastructure depends.

Like IT staffs of the past, today’s security professionals also struggle to demonstrate the value of what they do—you can’t ignore them, but it can be difficult to articulate what they bring to the table in tangible terms. Security is viewed more as protection or insurance, implemented to prevent bad things from happening. Measuring success, therefore, involves proving a negative: did nothing bad happen? What bad thing could have happened but didn’t because of the activities of your security team?

Although CISOs are beginning to enjoy more visibility and participation at the same levels as other executives, I still hear many complaints that security teams are relegated to the roles of providing supporting statistics to others and acting as a punching bag when things go wrong. Less often are IT security activities discussed in terms of the corporate value and bottom-line contributions they make to the organization. Focus tends to be on how the security function protects the value of others’ contributions rather than actually making its own.

I’ve had many conversations with security managers who are frustrated by their seeming inability to articulate their value to the rest of the organization, or who complain that they are not taken seriously as contributors to the corporate bottom line. Instead, they believe they are viewed as a necessary evil at best and, at worst, as active obstructionists who use fear, uncertainty, and doubt to make people’s jobs more difficult and complex. Part of this problem exists because IT security has not yet learned to translate its activities into the language of value used elsewhere in the business, just as other IT functions had to be expressed in different terms as they matured. Although the role of today’s CIO is still subject to political and organizational turf battles, most of these conflicts are couched in terms of how the CIO can stay competitive at the table with other CXO-level players and not whether the CIO has any right to be sitting at the table in the first place.

Some of the frustration about security’s lack of influence has resulted from the profession’s implied claims of exceptionalism—the idea that security is somehow different from other business activities. I’ve heard many times from security experts that what we do is as much, if not more, art than science. Not surprisingly, this is also a common argument against measuring security, given the belief that what we do somehow defies description, observation, or deconstruction. This approach to our professional activities does have its rewards, however. It is difficult to hold someone truly accountable for something that carries no hard criteria for success or failure. It is difficult enough for security management to deal with budget battles, political battles, and winning the hearts and minds of users without wanting to concern ourselves with the hard task of self-assessment and self-criticism. I believe that this can be a motivation against measuring our activities that is, unfortunately, difficult to resist. And the flipside is the frustration of not being able to explain ourselves fully to others and of not being recognized as real contributors to the success of our respective organizations.

But just as IT grew to be recognized as an independent business process of its own and not simply a technological enabler of other business processes, security is about more than simply protecting the activities and contributions of other, productive, parts of an organization. Security is an activity that consumes resources and produces outputs that are in turn consumed by the rest of the enterprise. This is the definition of a business process, and where business processes exist, so do opportunities to support the organization productively in tangible terms. But to manage security as a business process, security managers and CISOs will have to extend themselves beyond the technical aspects of security and take an interest in defining and measuring how security works in terms of the human, organizational, and economic characteristics of security and the associated costs and benefits that these activities bring to the organization as a whole.

Defining a Business Process

The first characteristic of a business process is that it involves activity, which means that it involves things happening and getting done as people and technologies interact. This may seem rather obvious, but it is an important concept. Activities are dynamic, implying action, interaction, and change. Activities are not static things. Think about how security is usually described within your organization. You probably hear statements such as “our security is good,” “security needs to improve,” or “the security posture of the network is weak.” These do not describe activities, however, and it is far less common to hear that the security of the organization as a whole is “acting according to plan,” or even “working properly,” although the latter may be heard when referring to a particular IT system. We just don’t talk about security as a set of activities unless we have to, preferring instead to abstract security to some general thing or force that is difficult to pin down.

Business process experts, however, understand that any process, including IT security, is in fact a structured series of activities that are conducted by individuals, groups, and machines working in concert. You cannot describe a business process as a single thing or an abstraction, because the process is always in flux as the activities that it comprises are accomplished. Instead, the process is described in terms of how well those activities function in support of the organization’s goals and objectives.

Consider human resources (HR) as another example of a business process. HR is usually not understood to be a single thing, but a collection of activities and people within an organization. It would be unusual to hear “our HR is good” unless the comment referred to the HR department and not some general state of HR goodness. If you want to test the theory that security does not typically refer to itself as a business process, just search the Web for “HR business process” and then for “security business process.” In the top hits for HR, you will find that human resources is described as a process of its own, whereas the top hits for security mostly appear as advice on how to incorporate security into the development of other business processes.

Security Processes

Looking at security as a set of activities helps IT security organizations better understand the low-level interactions that are necessary for security to function at all, from the activities of the firewall administrator, to the online habits of users, to the development of corporate strategy by the executive board. Any activity that either directly or indirectly impacts the security of the organization as a whole becomes part of the security business process and therefore subject to analysis.

From an IT security perspective, problems of coordination and collaboration that hinder the mission have always existed. In more than a decade of working with security clients, I have seen many examples of an almost willful failure to align the different stakeholders necessary for successful security programs. The divisions between the business and technical activities supporting enterprise security can be huge even within a single IT security organization. Getting the department to coordinate with other divisions of the organization such as Legal or HR is even more challenging. Consider the area of physical and logical security convergence. If a strong collaboration between common activity was to be found anywhere within a company, one would think it would be found in the joint development of corporate and IT security programs. But I have found that IT security teams are often no more closely aligned with facilities and physical security teams than they are with other organizational entities. This silo effect impairs the overall effectiveness of security operations by creating an environment in which no one really understands IT security and IT security doesn’t really understand anyone else.

IT security metrics require that the organization collect measurement data from a variety of sources. Protecting data and resources from harm and abuse cannot be localized to a single organizational unit, regardless of whether or not that unit is responsible for the protection. The activities that define whether or not a company is protected take place everywhere and they must be suitably addressed. A business process management approach demands that all activities that can impact enterprise security be subject to appropriate measurement and analysis. To this end, security managers must involve many other stakeholders and process participants in the overall security program if they are to continue to demonstrate the value of their unique activities.

Process Management over Time

The good news is that a long history and an equally large body of literature are devoted to the practice of managing business processes, and IT security can leverage all of this historical experience and expertise to articulate and promote the value of the security process.

Early Studies

Process management practices date back several hundred years to the beginning of the industrial revolution and involved the detailed analysis and restructuring of labor processes to introduce standardization and new efficiencies to the work performed in factories. In 1776, for instance, economist Adam Smith wrote about the division of labor in a pin factory as part of The Wealth of Nations. Smith described how, instead of one laborer being responsible for the entire construction of a pin, a team of workers each were given their own separate tasks in the manufacturing process. Smith calculated that this division of the assembly process enabled a single worker to contribute to the manufacture of hundreds of pins, on average, whereas that individual worker might find it difficult to manufacture a complete single pin on their own.

Scientific Management and Manufacturing

In the late nineteenth century, American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor began to apply rigorous scientific principles to the study of workflows in shops and factories. Taylor’s principles of scientific management refined the division of labor into highly organized, machine-like assembly lines of workers. The workflows and activities of these laborers were then extensively observed and studied to understand empirically how work was conducted and where inefficiencies or insufficient oversight might exist. As the factory process became more understood and controlled, work was then optimized to achieve maximum productivity for managers and owners, including such industrial giants as Henry Ford. Taylorism, as scientific management is also called, has been widely criticized for its overly mechanistic view of human beings as expendable parts of the factory “machine,” but Taylor’s influence is unmistakable and remains at the core of much of the working world today.

Process Analysis and Control

In the mid-twentieth century, a new approach to business process management began to emerge in the works of process and workflow researchers such as W. Edwards Deming, Walter Shewhart, and Joseph Juran. Working both in academia and in industry, these men developed new approaches to process analysis and management that built upon Taylor’s scientific management principles of empirical observation and methodical testing, adding concepts such as quality control and applying innovative statistical methods to the understanding and improvement of the processes and workflows they studied. Recognizing the importance of social and interpersonal factors in the business process, they also moved away from some of the more dehumanizing elements of Taylorism. Where Taylor’s work had served to separate managers and workers, consolidating power into the hands of the former so as to better control and manipulate the activities of the latter, the new view of business processes was more holistic and recognized the contributions of all sides to successful process improvement.

Another important aspect of process control was the concept of continual improvement of the processes being managed. Deming in particular contributed significantly to the promotion of continual process improvement through his creation of the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle, which remains widely used to this day. PDCA is even used in the security industry as the formal basis for the ISO 27001 international security standard. In creating PDCA, Deming drew from the scientific method, which involves hypothesis formation, testing, and analysis, as an inspiration. And like scientific progress in general, he emphasized the PDCA cycle as an iterative and continual activity occurring over time. Deming constructed PDCA, shown in Figure 4-1, as a wheel-shaped model that started and ended in the same place, articulating that the end of one iteration of the process was the beginning of the next iteration. The Deming Cycle, as PDCA is also known, can be recognized at the root of many improvement cycles today across a variety of industries, including security. Andrew Jaquith, who wrote one of the first books on security metrics, describes a funny and perverse variant of the cycle in which the phases remain but the original intent of continual improvement has been forgotten. Organizations on this “hamster wheel of pain” simply run around and around, repeating process phases without understanding what they are trying to accomplish, and getting nowhere fast.

Quality Control

Deming began his work in the United States, but it was in Japan that he enjoyed his greatest success. In the years following World War II, Deming was working to help the Japanese government recover and rebuild its destroyed industrial capabilities. By the 1950s, Deming had conducted extensive training of Japanese businessmen and engineers on his ideas for process improvement. These techniques primarily involved the use of statistical measures to analyze and control business processes empirically. Deming also introduced the concept of quality, tying increases in the quality of products to lowered costs and increased productivity and financial success. By continually monitoring and improving quality, Japanese businesses could make themselves more competitive and successful in the marketplace.

The Japanese embraced Deming’s work and advice enthusiastically, and during the next three decades, Japan grew into an economic superpower, successfully competing with and even surpassing other nations around the world, including the United States. In the 1980s, as a direct result of Japan’s success, Deming’s work was embraced and expanded upon in the United States, as American industry sought to compete more effectively with their Japanese rivals. Driven by the results of the improvements experienced in Japan, concepts such as quality management and process improvement became hot business concepts for the decade, as “Total Quality Management,” “Just in Time” manufacturing, the ISO 9001 quality standard, and other frameworks were implemented and adopted on the Japanese model.

Figure 4-1. The SPM Framework includes security metrics, security measurement projects, and the security improvement program.

Business Process Reengineering

You may see a pattern emerging here. As the analysis and improvement of business processes emerged historically, researchers continued to expand and develop the ideas and techniques that came before. The 1990s were no different, as the next phase of process improvement took shape. Business process reengineering was a response to the idea that continual process improvement frameworks such as TQM and process control were not sufficiently radical. Process improvement experts such as Michael Hammer and James Champy were concerned that the attempts to improve process efficiencies were inefficient themselves, concentrating more on automation through technology and streamlining workflows. They argued instead that processes needed to be completely reengineered, and those processes that were not valuable completely done away with. Similar arguments were made by other reengineering proponents such as Thomas Davenport, who believed that only by completely rethinking the business process (as opposed to simply improving the one in place) could an organization achieve the gains in activity that were needed to compete in an increasingly technological and global marketplace.

In the case of process reengineering, technology began to play an increasing role as both a driver and an enabler of change. New information technologies were beginning to displace traditional manual processes, and the reengineers looked for ways to leverage these technologies to reshape the workplace completely rather than be satisfied with incremental improvements to business as usual. In a similar fashion, the availability of new technology allowed for more sophisticated analyses of the processes themselves. Organizational activities could be tracked, charted, analyzed, and monitored through the use of technology in ways that transformed the older, manual ways of accomplishing the task. As a result, organizations could afford to build process improvement into the workflows themselves, rather than depending on outside experts to conduct more expensive and disruptive reviews periodically. This allowed for the capability to collect more “real-time” continual feedback on processes and more input from everyday workers, although not everyone implemented such improvements in the same way or to the same degree of effectiveness.

Business Process Management

By the late 1990s, business process reengineering had also taken some hits, as companies used the concept as an excuse to cut costs, jobs, and benefits in the name of efficiency and productivity. Many of the same critiques of Taylor’s scientific management were applied to business process reengineering as a way of ignoring the human aspects of the organization in favor of a more mechanical view.

And so the history of business process improvement continues. As I write this book, the current preferred term for referring to the analysis and improvement of business processes is simply “business process management.” At its most basic level, business process management involves the active measurement and analysis of the activities of the business to understand and improve them. Some process improvement techniques are about identifying redundant activities and eliminating or combining them through automation. Some are about understanding where the process may yield opportunities for growth or additional value.

Many frameworks are available for managing business processes, all building upon the historical development I have outlined here, dating back to Smith’s description of the pin factory. Some are proprietary frameworks promoted by consulting companies and others are more generic guidelines for tracking activities. The framework outlined in this chapter is an application of business process management for IT security and is designed to be both usable and practical, and I specifically address security process improvement in examples later in the book. My recommendations are not a revolutionary new twist on how to do this sort of work. They represent one way that you can adapt these ideas to measuring and improving your security over time.

The SPM Framework

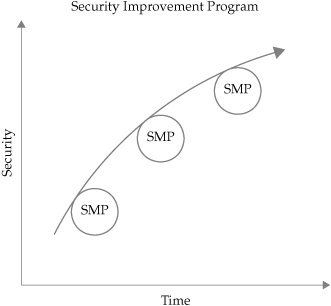

The SPM Framework allows you to structure your security measurement activities into a structured yet holistic approach to improving security over time. The framework is iterative and built upon several components that are then structured into a continuous program for managing security as a business process. The SPM Framework is illustrated in Figure 4-1. At the lowest level of the framework are the security metrics you identify to enable the measurement, analysis, and assessment of your security process activities. But, as I’ve discussed, metrics are far less effective when they are ad hoc or unstructured aspects of the security program. The GQM method described in Chapter 2 is an elegant and easily understood way of bounding and aligning metrics with a specific goal, but even GQM-derived metrics remain relatively tactical and more suited for specific projects than as strategic activities.

The project-specific nature of GQM can be carried a step further. Strategies are never accomplished at once, but are the result of well-coordinated sets of interrelated objectives and actions. The SPM Framework’s strategic approach to security involves the coordination of many different project-level activities, somewhat obviously called security measurement projects (SMPs), in which bounded security measurement initiatives are undertaken, tracked, and coordinated into a larger system. These projects allow you to tackle security improvements in manageable increments that document and align the specific goals of the project with the larger goals that exist across projects as part of an overall program to improve the organization’s security.

This modular approach to security measurement supports a larger, strategic Security Improvement Program (SIP) that works to combine, coordinate, and align the activities of all the various measurement projects into a system of continuous measurement, analysis, and improvement of enterprise IT security. Under the SIP, metrics and project results are cataloged and retained for future reuse and projects are cross-referenced and incorporated into organizational learning systems to create security knowledge management and experience sharing across the organization. The end result is SPM, a capability maturity in which a broad selection of IT security characteristics, including people and organizational process as well as technology, is understood, measured, and continuously improved.

Security Metrics

I have spent several chapters digging into the topic of IT security metrics, so instead of rehashing that material, let’s just leave it at the fact that your metrics are the engine that drives your SPM Framework initiatives. In fact, SPM exists primarily as a way to organize, structure, and keep track of the various activities that you are doing to measure your security. The framework ensures that metrics are developed and addressed in a bounded, manageable way over time and that the results of these activities can be remembered, learned, and used by the organization long after the original project is completed.

Think of the growth of human knowledge, moving slowly along on a foundation of observations, experiments, and analysis. Experiments and observations may have been the core of the process, but it took the conceptual framework of the scientific method in the seventeenth century to kick-start that growth, standardize it, and make the results available to others who may have wanted to replicate and build on preexisting work. Metrics without a structure for long-term exploitation of the measurements will never allow you to reap the full benefits of your efforts.

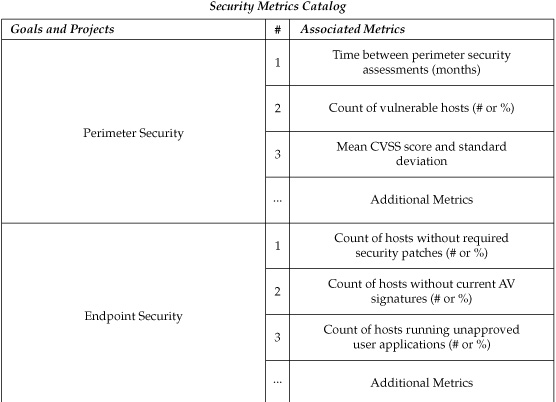

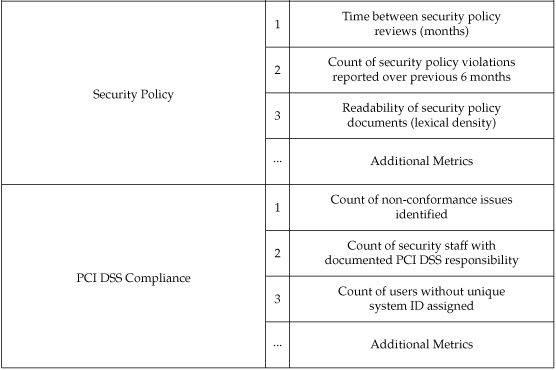

The GQM method keeps your metrics bounded in the service of specific goals and provides a good organizing principle of its own, acting as a natural way of designing security measurement projects around particular metrics goals. GQM also represents a good mechanism for classifying and cataloging your metrics for future use. Constructing a metrics catalog with cross-referenced goals and questions can enable you to build institutional memory and avoid repeating steps unnecessarily. A metrics catalog does not have to be anything fancy so long as it keeps track of the metrics you have already developed and used, organizes them in some way, and is easily available for your team (and possibly others) to use and draw upon. A process of review should also exist, in which metrics are assessed, updated, or removed. Wikis are a great way to develop a metrics catalog that can be easily shared and updated in a collaborative environment, but a simple document such as the one shown in Figure 4-2, posted to an internal server where it can be found and downloaded, can also work quite well with minimal overhead.

Security Measurement Projects

SMPs are the building blocks of your security process management. I will cover the process of setting up measurement projects in detail later in the book. For now, you should know that SMPs allow you to break down the complexity and size of IT security into manageable chunks of inquiry that can be defined and observed in a realistic way. SMPs can be applied to anything you want to explore or understand. If you can articulate a desire to know something, then you can build a measurement project to delve into it, using the GQM method to figure out what you want to accomplish and what metrics you have to develop and explore to get there. In this way, the SMP concept adds to the practicality of metrics in general as projects are naturally customized to the unique needs and goals of your organization. At its core, the measurement project is just the logistical and organizational structure that you employ with regard to your security goals, questions, and metrics to see them to completion.

Figure 4-2. A simplified security metrics catalog organized by previous projects and listing the metrics that have been used for those projects adds value by allowing you to track and reuse what you have already built.

SMPs create context and documentation for your metrics and tie together your measurement efforts. For most organizations, this is less about actual projects and more about a state of mind. Every organization has security projects, just as every organization collects metrics-related data. The challenge is looking at these projects as links in a chain of effort that naturally lead to other links, other projects, and other findings. I see this most often in customer consulting engagements when it comes to remediating the problems identified during an assessment or a review. The two tasks are viewed as different activities rather than as two components of the same activity. The results are delivered and the consultants leave, at which point a separate project must be set up to address the issues. Under the SPM Framework, all projects are components of an integrated activity, with inputs from some projects and outputs to others. Smaller goals are rolled up into larger goals, metrics into broader understanding, and security capabilities mature and grow more embedded over time.

The Security Improvement Program

The strategic goals of every security team include reducing the risks posed by security threats, improving the effectiveness of their security operations, and adding value to the organization. These goals drive security staffs to assess and improve what they do. But improvement often competes with day-to-day operational management of those systems and the security program in general. It is difficult to stay focused on the future when the present is constantly calling the help desk or showing up at your office door to ask where your budget inputs are prior to the upcoming ops review. And it never helps that there are not enough people or funds to go around. As a result, many security programs remain rooted in the immediate, tactical requirements of daily security operations.

Continuous improvement of anything, including IT security, requires that the efforts to make things better be done in a consistent and coordinated way, not as piecemeal exercises that could be easily forgotten or neglected as the next task appears in our inbox. You do not train for a marathon by running whenever you have the time, nor do you get an advanced degree or certification by taking classes and studying when it is convenient. All genuine improvement in the quality of effort requires a commitment to that improvement.

The SIP works within the SPM Framework to provide a structure for that commitment, just as the GQM method structures your design of metrics and a security measurement project structures your enactment of those metrics. The goal of the SIP is the explicit linking and coordination of individual measurement projects over time, as illustrated in Figure 4-3. The SIP accomplishes this coordination by leveraging documentation, activities, and feedback tools to facilitate organizational learning and capabilities maturity. Like the rest of the framework components, I will discuss techniques for SIP development later in the book. For now, the key takeaway is that the improvement program functions as an organizational control plane for measurement projects, metrics, and data. Under the SIP, projects are coordinated with other projects, with collaboration across project teams, and documented through measurement project catalogs much like the metrics catalogs discussed in the preceding section. Over time, data becomes information, information becomes knowledge, and (hopefully) we all end up wiser as well.

Figure 4-3. The SIP links and coordinates individual measurement projects over time for continuous security improvement.

Security Process Management

At the top level of the SPM Framework, supported by all the work occurring in the phases and activities below it, is the attainment of ongoing security process management and continuous improvement of your operations and initiatives. The benefits that result from measuring and coordinating security processes and from sharing and reusing the results can be profound. From an operational standpoint, SPM gives more insight into the mechanics of security and backs up these insights with empirical data that can be used to support budget and resource requests, audits, and reporting requirements. Better understanding of the security process also contributes to decreased risks and losses due to security breaches and incidents. Perhaps even more powerfully, SPM can enable security management to articulate the value of their efforts and activities in language that is understood and accepted by business stakeholders outside of the security group.

Whether metrics let you better quantify the losses that your program prevented or, by analyzing and improving the efficiency of your security processes, allow you to cut costs and increase productivity in existing operations, you’ll find that you can describe and explain how security supports the business beyond being just an insurance policy.

Research has also shown that effectively managed processes pay off for organizations in more ways than just preventing security problems. A 2008 research study by the IT Policy Compliance Group (available at www.itpolicycompliance.com/research_reports) found that managing IT processes (including security processes) effectively provided double-digit increases in revenue, profit, and customer satisfaction and retention. Such increases make sense when you consider that they do not result from new product implementation, or the fact that the firm has an audit done every year, but rather from a true commitment to process improvement and maturity.

Continuous process management and improvement of the kind attainable through the SPM Framework and the SIP structure are the objectives of a number of process-oriented conceptual frameworks that are increasingly being considered by security managers and consultants. Frameworks such as Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT), Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), Six Sigma, and several of the special publications of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) all promote the need for more mature, continuously improving security processes and offer paths by which an organization can achieve sustainable improvements. The SPM Framework is not intended to replace or compete with these other frameworks, should they be in place. But as I have developed the idea for the framework over time, I saw the need for something a bit more practical and easier to grasp. Other potential process frameworks for security tend to be proprietary (and expensive), increasingly complex and theoretical (and thus more beneficial to consultants than to operational security managers), or too specialized and focused on checklists and standard techniques to encourage out-of-the-box experimentation.

To recap the SPM Framework in simple terms, the general idea is this:

1. Develop metrics, ensuring that your measurements are appropriate and well-designed using the GQM method or a similar alternative.

2. Collect and analyze your metrics data through bounded, well-defined security measurement projects. Projects can be built around anything you want to measure and can include quantitative metrics, qualitative studies, experiments, or documentation exercises as meets your needs. Share and save the results.

3. Make a commitment to treating measurement projects as components of a larger security improvement program and not just separate or stand-alone activities. Document them, make the results easily accessible, and build upon them to create new projects based on what you have learned.

4. As you gain insight into how your security programs are working, employ processes to analyze and improve how you measure as well as what you measure, so that you achieve continual, sustainable management of security as a business process just like any other in the enterprise.

As much as I would enjoy claiming credit for discovering some new truth about IT security management, the SPM Framework and the techniques for implementing it are not revolutionary. Many of you are already performing some of these activities in your own programs. I don’t claim that the SPM Framework is the only way to measure and improve security. If you are already doing things in a certain way, and those things provide some of the same results as those I discuss in this chapter, you should not change them just because I describe how to do those activities differently. But I do believe that any security program that does not include well-designed metrics and a variety of different measurements of different aspects of security, or that does not undertake those measurements within the context of a larger program of continual process improvement, is going to be much less effective. I also believe that if you do not explicitly understand and treat your security management as a business process just like HR, manufacturing, or sales, with associated input sources, products, and customers, you are missing opportunities to be taken more seriously and articulate the true value of your security efforts. The SPM Framework is meant to be a fairly straightforward and practical method for structuring your security to achieve both of these goals. Adopt it, tweak it, or discard it in favor of some other framework that meets your unique institutional needs, but put something in place if you don’t already have that structure.

Before You Begin SPM

One of the ideas behind security process management and the SPM Framework is that you can start anywhere. Implementing SPM does not mean that you have to launch a formal, company-wide initiative with all the associated trumpets and internal memos. In fact, I’d recommend against that approach for most security organizations, unless you already have support and resources from senior management (or you are the senior management and you have the ability to make the program happen yourself).

A successful SPM program will address only as much as can be immediately influenced by the stakeholders of the program. You cannot expect others to buy into your vision strictly on the basis of that vision—most will want to see some results first. Of course, once you can produce those results, you may want to begin bringing other stakeholders such as internal audit into your efforts, as these teams are more likely to “get” what you are doing and can act as a force multiplier as you take the security message to others.

By keeping initial SPM efforts local, limited perhaps to a security measurement project or two, you can keep control of the effort and build a pilot program with results that you can use to justify expansion into a larger initiative. This approach is not much different from deploying a new technology or starting a new branch of scientific exploration. You don’t change everything and rewrite all the textbooks until you have built up your credibility through initial stages of development. Security metrics are no exception.

Getting Buy-in: Where’s the Forest?

A standard mantra of process improvement and project management of all stripes is that you have to have some level of sponsorship and support to be successful. Pick up almost any book on the subject and you’ll read very early about the need to get management buy-in for your efforts. This is certainly true as you work to improve security across the organization. The first question you should ask yourself when considering security metrics or SPM is “what large-scale issues am I attempting to address?” Metrics are usually local. They tend to be specific sources of data and of primary interest to those closest to them. But to make a metrics program work beyond the immediacy of security operations—for instance, to argue for bigger budgets or more clout at the executive table—your security metrics must mean something to more than members of the security audience. Understanding the boundaries of the impact you want to make with your security metrics and process improvements will define the scope of your process management program.

It is easy to get bogged down in all the cool data that is available through measuring various aspects of your security. You begin to gain visibility into your operations that you might have only dreamed about. But a much more detailed operational knowledge of security, thanks to your metrics, is not a guarantee that anyone else will care. Deciding on the scope of your efforts before planning your security metrics program can save you a lot of frustration and false starts. For many stakeholders elsewhere in the organization, the nuances (or even new characteristics) of system or security performance that you discover will not be relevant to the things they care about. If you want to make security important to these people, you must understand what they consider to be important and then figure out how security affects those things. In other words, security is often about understanding how security does not help the business, whether this is due to lack of direct support to a business need or because those benefits have not been articulated effectively. Show stakeholders how security can improve their personal, political, and economic situations and you will find that you suddenly have a lot of support.

In the beginning, you may not even be able to see all the trees, much less the forest. The challenge sometimes facing those looking to improve security is that it is difficult to describe how your efforts will meet the needs of others if you don’t understand those efforts yourself. How do you get buy-in to accomplish something you cannot fully explain?

One of the benefits of starting small in SPM is that you don’t need a lot of buy-in. The metrics, projects, and process improvement described by the framework can be accomplished even if you don’t manage anything but your own daily activities. One friend of mine, for example, began a new job in a consulting practice, delivering security assessments. As he finished his training program and started conducting his own engagements, he found several areas of the process inefficient, negatively impacting his productivity. Being the kind of engineer that he was, he quietly set about analyzing and changing his own workflow. He didn’t complain about the old way of doing things or propose a study—he simply figured out a better way to do the work. Then he showed others what he had done. Within a couple months, management had gotten involved, the entire practice had adopted his changes, and he was being asked to analyze other elements of the practice. Buy-in follows results.

Requirements Analysis

Understanding what you want to achieve and how that integrates with what others want to achieve can be an important first exercise for an SPM program. The analysis does not have to be formal or particularly methodical, although as your program grows and you gain more experience, you may find it valuable to capture and refine this data through a formal process. But at first, your goal should be simply to help yourself understand what you want to accomplish and who you might need to sell on your vision in order to see it to completion.

Drivers Like the goals that lie behind our metrics, we often neglect to consider fully why we are doing something. The risk assessment is a classic example, in that we will often talk about the primary driver being improved security when, in fact, the primary driver of the assessment is that some authority (a law or standard, an auditor, or our boss) told us we have to do one. Understanding the motivations and reasons behind our security activities makes them much easier to analyze and improve, but getting there can be difficult.

Sometimes, the reason we claim to do something is not really why we do it. A company might implement only enough security to meet minimum regulatory requirements, but it is not politically correct for management to say they don’t care about security as much as they do passing an audit. The public story will always be that protecting company information is paramount. This is not a book on corporate ethics, so I’m not going to address the philosophical problems here. My point is that misleading yourself and misleading others about motivations and drivers creates inefficiencies, requires extra work, and costs money. Realistic analysis of the goals behind your security processes and measurements allows you to identify actual areas of improvement. Consider some of the high-profile security breaches in which companies that claimed to take security very seriously, and were even certified as doing just that, became victims, because it turned out that much of their security was on paper. It doesn’t matter whether or not a particular company behaved badly—what is important is that any savings they might have achieved by skimping on some aspect of security was offset by the costs incurred when their security failed.

What are you really trying to accomplish? If you want improved security in some form, that requirement should drive your SPM efforts in a certain direction. If you need more budget, a successful audit, or a particular certification, those needs serve to define what you need to do. Realistically assessing your drivers and motivations also allows you to consider other questions and ramifications of your program, such as the politics involved with taking resources from other parts of the business or the consequences of a security breach on your reputation if you have been doing lots of audits but failing to remediate the problems you found.

Stakeholders Stakeholders are those who stand to benefit from (or lose as a result of) your efforts. These are the people you will depend on for resources or data, the individuals who will make money or save time because of what you discover, as well as those who may be threatened or inconvenienced by changes in the security program. If you are a security manager implementing metrics for your immediate team and processes, your main stakeholders might be limited to your own group. But it always pays to consider the bigger picture. Thinking about how you can win new support from nontraditional areas of the business by adapting your SPM program can give you new ideas on how to construct goals, questions, and metrics. Likewise, understanding potential conflicts with other teams can help you work through problems before they become a risk to your security program activities.

Stakeholder analysis is one of those areas where security practitioners within an organization can really improve their efforts by developing novel approaches to security measurement and process improvement that meet the needs of others. Reaching out to peers in areas such as HR, finance, or sales and asking, sincerely, how the security team can support them and then working to provide those benefits can prove very valuable. Of course, don’t expect these stakeholders to be waiting for your call. You may have to explain exactly what you do, and you may have to listen to complaints about how security makes their jobs more difficult. But if you can get others talking to you and you listen to what they have to say, you may get some new ideas about where your program can meet your own needs and result in alliances with other parts of the organization.

Resources Resources are never as abundant as we would like, and in today’s economic climate they are positively scarce. One of the reasons for launching an SPM initiative is to justify the resources being spent on security (and, hopefully, to make the case that more resources are justified). But, as the saying goes, you have to spend money to make money, and adding new metrics and data analysis to your program is going to require resource commitments.

Depending on what kind of security measurement projects you attempt, you may need to leverage resources outside of your own immediate team. It is important to understand the resource requirements of any metrics or data gathering activities you undertake as well as the requirements of the security measurement projects that are ongoing. As your program expands into continual process improvement, you will find that you need additional resources to ensure that the program can function (although at that point the goal is to have so thoroughly demonstrated the value of continual security improvement that you do not need to argue very hard for these resources). Some things to consider:

![]() What data sources will you need? Do you control them? What are the costs of accessing these sources, either to you or to other owners?

What data sources will you need? Do you control them? What are the costs of accessing these sources, either to you or to other owners?

![]() How will you analyze data from measurement activities or security processes? Do you have the tools and skills in house for statistical or other types of analysis?

How will you analyze data from measurement activities or security processes? Do you have the tools and skills in house for statistical or other types of analysis?

![]() Have you considered the resources involved in addressing any findings you may develop through your program efforts? If you find major risks or opportunities for improvement, do you have the ability to act on them quickly?

Have you considered the resources involved in addressing any findings you may develop through your program efforts? If you find major risks or opportunities for improvement, do you have the ability to act on them quickly?

![]() How will you present your findings and recommendations? How will you use your measurement results to convince stakeholders, particularly those who have provided you with data to begin with, that changing their security behaviors and activities will be to their benefit?

How will you present your findings and recommendations? How will you use your measurement results to convince stakeholders, particularly those who have provided you with data to begin with, that changing their security behaviors and activities will be to their benefit?

Setting Expectations

The end goal of the SPM Framework is nothing short of a transformation of your security operations into a better managed and more mature business process. This transformation may be huge or it may be specific to particular areas, depending on how well your security program is currently governed. But in either case, the transformation will and should be gradual. A potential trap of any business process improvement initiative is that the organization tries to do too much, too fast. Someone attends a conference, takes a training course, or reads an article or book (oh my!) on implementing a process improvement framework and the next day comes into the office fired up to change everything. But turning an entrenched process on a dime doesn’t work in real life and it will not work for your security program. From oil tankers to our personal lifestyle habits, you don’t just decide “now I’m going that way” and instantly alter your circumstances. I have even see this occur with security metrics, as one or more individuals within the firm decide metrics are the answer to improved IT security and thus begin to measure everything without even thinking very much about what they really want to achieve. Usually these efforts end up unsustainable, putting out more light than heat and fading quickly. While it may feel more gratifying to dive into action in the face of a problem, it is more important to put a process into place that has staying power derived from clear definitions and well-formulated planning.

So expectation setting is key to successful metrics and to implementing SPM successfully. You have to set expectations for others and, equally important, you have to set them for yourself. On the one hand, measuring and improving security is going to require you to expend resources. However small you start, you are probably going to have to do some new things and learn some new skills. And as you tackle bigger questions requiring more (and different kinds of) data, or as you employ the structures for security improvement and continual process management, those resource commitments may increase. It helps to be ready for this. You also must make others ready for what you are going to do, and this often means explaining how massive transformation and savings is not going to occur overnight. Working with your stakeholders to identify clear, attainable objectives for measurement that you can build upon going forward is the best strategy when starting your program.

I think that one of the reasons IT professionals in general like big, broad transformation projects is that incremental change is at odds with our belief in how smart we are and how cool our technology is. Everyone wants to start a revolution, it seems, but revolutions can be violent and messy (just ask anyone at the heart of a large, failing enterprise resource planning [ERP] implementation). I prefer knowing each day that I am a bit better than I was the day before, that I have every expectation that I will be a little better tomorrow, and that I can keep it up indefinitely.

Showing Results

Setting realistic expectations is important, and just as important is the need to meet those expectations with tangible results. Earlier in the chapter I discussed how security managers often struggle with a lack of credibility with other business owners given the difficulty in expressing the value of security in terms those owners understand and care about. The upside of this challenge is that as long as nothing blows up, the security team can make the argument that they have delivered the results expected. But such absence of true accountability is not optimal or sustainable, and it certainly does not survive the first failed audit or high profile breach. The downside, of course, is that the security manager is never able to bring real value to the table. At worst, he or she becomes a functionary, making reports and keeping track of logs in an effort to prove that the security team is actually doing anything productive at all.

Results of IT security metrics and process management can take many forms, including these:

![]() Visibility into the real costs of protecting systems and data, and reductions of those costs in direct support of the bottom line

Visibility into the real costs of protecting systems and data, and reductions of those costs in direct support of the bottom line

![]() Demonstrating to other business units and stakeholders the value of information and the associated real costs of protecting corporate assets

Demonstrating to other business units and stakeholders the value of information and the associated real costs of protecting corporate assets

![]() Positively affecting corporate goals such as productivity, revenue, and profit through improved compliance and IT governance

Positively affecting corporate goals such as productivity, revenue, and profit through improved compliance and IT governance

![]() Building internal and external customer satisfaction on the basis of understanding markets for security improvement, attitudes towards protecting corporate assets, and motivations for why people do or do not exhibit good security practices

Building internal and external customer satisfaction on the basis of understanding markets for security improvement, attitudes towards protecting corporate assets, and motivations for why people do or do not exhibit good security practices

The Security Research Program

Many of the security practitioners with whom I’ve discussed metrics and process get a little hesitant when I begin talking about that exploration as a research program. This is one of those cases where having a Ph.D. actually adds to the problem, because I say “research” and people start to think I mean academic activities that are complex, theory-heavy, and unlikely to provide the immediate benefits they are looking for or need. Even in security, “research” tends to refer to work that is separate from daily operational activities, unless you are a security researcher looking into specific areas of interest such as vulnerability discovery or botnet tracking. The discoveries made through this research may benefit day-to-day operations, but probably not directly and not immediately.

The security research program I advocate is more practical and relevant, involving far more applied research (research geared toward solving a real problem and not just for the sake of new knowledge) than basic research. In this way, it is more like the research programs for marketing, advertising, or manufacturing. The goal of a security research program is to understand the security environment and the forces that govern it so that you can better influence and control them. There may be a place for exploratory research within your security program, but you will probably find as you begin to measure and manage your security that there is plenty of low-hanging fruit available in terms of process improvement without getting overly creative with your research. You should think of your research as supporting the understanding and improvement of your business, as though you were an entrepreneur looking to attract potential venture capital or a consumer product firm hoping to capture a new market.

The point of considering your activities as a research program instead of, say, just a security metrics program is that a focus on metrics is simply a focus on data. With metrics, all you need to do is measure. Looking at what you do as research keeps you focused on the prize: new information and knowledge that you can apply to a greater purpose. The SPM Framework provides a good structure around which to build the research program, to document and champion your security management agenda, and to benefit from your results.

I like the research program trope because I have an academic streak and I think research is enjoyable. If the research program is not working for you or does not keep you engaged, then find another way of looking at it. If you have an entrepreneurial spirit, treat your security process management as a new business venture and draw up a SPM-aligned business plan for your program rather than a research agenda. If you are more of the artistic or literary type, use the metaphor of a novel or a screenplay in which you have to tell the story of security for your organization, including characters, motivations, and ongoing plotlines. The point is to develop a way of thinking about security holistically that gets you literally “out of the box” and gets the processes your organization uses to drive business into people’s heads. In any of these examples, you will find that you still need to understand your resource needs, drivers, and stakeholders and to organize your metrics, projects, and improvement program to make your new venture successful. Whatever helps you to do it, you want to take a big-picture approach to how you comprehend your security, building on the metrics you develop to ensure that you have a structured and coordinated means of putting them to use.

Summary

Effective metrics are an engine for improved security, but taken on their own they can lead to an overemphasis on measuring and data collection without a larger contextual framework to guide and coordinate the work. To be successful in an increasingly challenging environment of compliance and business accountability, you should treat and manage security as a business process rather than primarily a technology issue. Security managers and CSOs today often struggle with an inability to articulate the value of their activities and hold themselves accountable to the same metrics and priorities as other business owners. Understanding and managing security as a business process can help your security organization improve both operational and organizational success.

Business processes, including security processes, are activities that combine the efforts of people and technology working in concert toward organizational goals. Understanding these processes includes measuring and analyzing social and organizational aspects of the business environment in addition to the technological components of these processes. The analysis and improvement of business processes has a history dating back centuries to the beginning of the industrial revolution. Over its history, business process analysis has included increasingly sophisticated methods of observing factory work, scientific management theories, statistical process analysis, quality improvement, and most currently the reengineering and management of business processes to achieve continuous improvement over time.

The SPM Framework offers a practical, flexible structure on which you can build more effective security operations. The framework includes well-designed metrics, the analysis of which is accomplished through independent, focused SMPs that provide a vehicle for coordinating metrics within a standard project management plan. Measurement projects are not conducted in a vacuum, however, and the framework includes a SIP that builds organizational learning and knowledge management to enable metrics and projects to be leveraged and reused over time. As these processes improve, your security program achieves greater capability maturity and continuous improvement, while meeting management requirements for the data and insight necessary to demonstrate value and accountability throughout the business.

Before beginning an SPM Framework initiative, it is important that you consider issues of buy-in, including understanding the drivers, stakeholders, and requirements for security and security knowledge beyond your immediate security stakeholders. Setting proper expectations and delivering results can help you gain support and cooperation from areas of the business that may not have previously supported or given credibility to security.

Further Reading

2008 Annual Report: IT Governance, Risk, and Compliance—Improving Business Results and Mitigating Financial Risk. IT Policy Compliance Group, 2008. Available from www.itpolicycompliance.com/research_reports.

Jaquith, A. Security Metrics: Replacing Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt. Addison-Wesley, 2007.