CHAPTER 10

Measuring People, Organizations, and Culture

You’ll find the measurement and analysis explored in the project examples of this chapter somewhat unconventional in their approach, especially if you are accustomed to thinking about security and its measurement primarily in terms of technology or the quantifiable, easily obtained metrics data with which many security professionals are most comfortable. Given that you have read this far, you already understand that I am no enemy of quantitative analysis, although I do think that qualitative techniques are neglected and underutilized in the security industry. This neglect is ironic, since the majority of our measurements are qualitative in nature—it’s just that the qualitative inquiry we undertake is typically haphazard and not very rigorous. (Which, in turn, is often justified by the misinformed and self-serving argument that there is no way to be rigorous since our methods are so qualitative!) The idea that we have to choose between (supposedly) vague and subjective measures of security or else we must completely embrace numbers as the only true security metric sets up a false dichotomy that hinders our ability to accomplish our mission: to protect the information assets of our respective organizations and, increasingly, our information and IT-dependent society.

Let’s look at another type of security as an example. Suppose you were asked to measure the national security of the United States. How would you respond? You could certainly cite the size and budget of our military, the number of nuclear and conventional weapons we possess, or the response time involved with focusing satellites or other intelligence-gathering capabilities on a new trouble spot. You could even compare those figures with those of our rivals and competitors. But would those facts accurately measure national security? Of course not—although the data would provide certain insights into the concept of national security, the reality is too complex and broad to be defined by any single set of metrics. You would also have to consider qualitative measures of security, such as the political stability of our society or our ability to create and maintain alliances with other nations. These metrics are also central to the picture, but they are not easily quantified, and you can find similar measures in economic security, transportation security, or (drum roll, please...) IT security. In fact, most recently as a result of high-profile attacks such as those conducted against Google in early 2010, IT security has begun to be defined in terms of national security, so our knowledge of the former influences our analysis of the latter.

To measure one of these macro-level concepts completely, you would have to be able to measure every aspect that creates or informs that concept. In the case of IT security, this includes not only IT systems, but also the organizational structures, people, and even the social and cultural norms that impact and are impacted by the effort to protect information assets and information capital. And many of those elements of security are conceptual; therefore, they are measurable only in conceptual terms. There is no “culture” command in your security management system that will tell you everything about the shared practices and beliefs of your enterprise. But this does not mean you have to give up on understanding such things as culture or organizational (meaning human rather than technological) behavior. The opposite is, in fact, true: you must understand these aspects if you are to understand and effectively manage your security and risk management operations. Security infrastructures are not made up of machines, but of people. Machines are simply the tools people use. The same holds true for threats and attackers. People are central to IT security—from the attackers who imagine and design sophisticated technical exploits, to the marketing people who try to convince us that technology can solve our problems by automating people out of the equation, to the user who clicks his way into a botnet because he lacks the awareness to distinguish an advertisement from a trap.

The two example projects in this chapter are designed to stimulate your thoughts and further discussion on ways that we can measure things that we often consider “immeasurable” in our security programs. These projects make use of data, techniques, and tools that have long and productive histories in the social sciences and in industries outside information security. They are often messy, time-consuming, and dependent upon interpretation and consensus. But, when used properly, they work exceptionally well at providing important social and cultural insights into your security operations that all the numbers and security event correlation tools in the world will never provide. So, by all means, be skeptical. (After all, skepticism and self-reflection on the part of the researcher are two of the hallmarks of rigorous qualitative research design.) And while you are at it, take some of that healthy skepticism and apply it to the question of whether the metrics data (quantitative or otherwise) that you collect today allows you to answer any of the questions that are posed in the pages to come.

Sample Measurement Projects for People, Organizations, and Culture

Both of the security measurement projects (SMPs) that follow used novel measurement techniques to arrive at findings and conclusions about very traditional security challenges, such as how to promote the value of the CISO to other business units and functions and how to drive better security practices down into the organizational culture and fabric. The project teams involved relied on analytical constructions such as stories and metaphors to explain their security operations. At first glance, these targets of analysis may appear to be very unscientific indicators of the tangible and factual elements of a security program; however, they are at the basis of how all of us, including scientists, understand the world. Equations are great, but they rarely explain why you should care about them. When applied to security, conceptual communication vehicles can provide context and strategic insight into which more targeted and specific metrics can be utilized.

Measuring the Security Orientation of Company Stakeholders

This example measurement project was conducted by a medical technology company with a progressive security team. The CISO had been brought in with the full support of the CIO after the company had experienced several security incidents in previous years, including one that had resulted in the loss of valuable intellectual property that had negatively impacted annual revenues. As a result, the security operations group was heavily involved throughout the company, setting standards, developing security policies, and conducting audits and assessments. The downside of the situation was an increasing resentment of the security group’s activities as overly meddlesome and an attempt by the CISO at “empire building.” Complaints had been increasing about security charge-backs for required projects, and the CISO was told by his boss that some business units were telling him that “the security bureaucracy” was impacting the company’s ability to stay competitive.

Building a Security Outreach Program

The CISO took these concerns and complaints seriously, because he realized that the CIO’s support was the main factor that enabled him to accomplish many of the security initiatives he had rolled out. The CISO, while sympathetic to the impact of security on other business activities, also believed that many people in the company resented having any security requirements at all and wanted to return to the more relaxed attitude toward security that previously made the company vulnerable to attacks and security-related losses. This obviously was not an option, but the CISO understood that his team needed to do a better job of selling themselves and showing others in the company the importance of protecting their information assets.

To accomplish this goal, the CISO set up what he called a “security outreach” program for the company. With the direct support of the CIO, the security team developed a program that was designed to move the security group from the role of cop or watchdog to that of valued partner to the various departments in the company. Changing the perceptions of the security operations group would require two strategies: The CISO needed to educate critics and convince them that security was enabling rather than limiting their operations. But in defining the strategies, the security team realized that they didn’t know very much about the security needs and concerns of the rest of the company. Security direction and requirements were set within the CISO’s team and then communicated outward, and that direction was of a one-size-fits-all variety, with set standards and requirements to which everyone was required to adhere. As a result, the CISO realized that he first needed to educate himself and his team as to whether their claims that security was enabling other company stakeholders were true. If security was indeed limiting productivity and efficiency, then the CISO needed to know that before he could hope to make improvements. To get the buy-in that he needed to be successful, the CISO realized that his team needed to do much more listening.

Conducting an Information Audit

To assess the unique information security needs of the other stakeholders throughout the organization, the CISO set up a measurement project to conduct an information audit. Unlike an IT audit that focuses on systems or a security audit that explores weaknesses and gaps in the overall security posture, an information audit is a specialized assessment that comes from the fields of information management and information policy development. Information audits aim to understand what information assets are in place within an organization as well as how information flows and is used by the organization’s members.

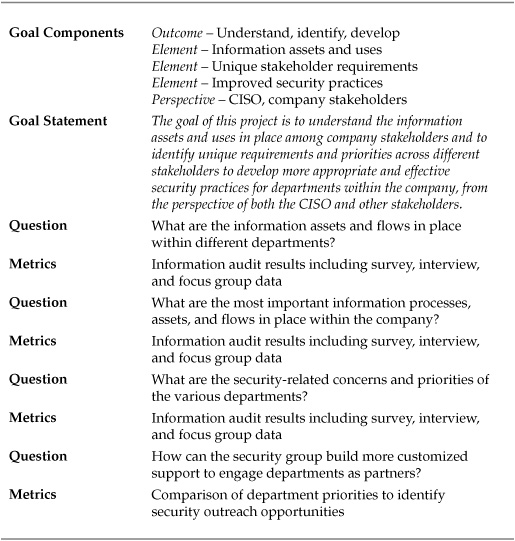

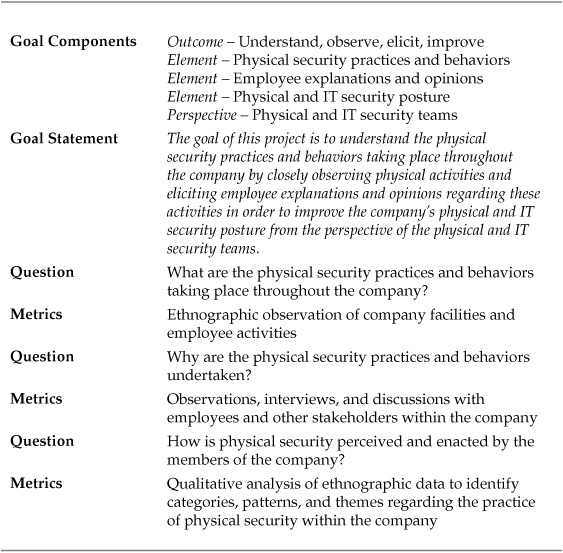

Working with a consultant who specialized in information auditing, the security measurement project team wanted to adapt the information audit methodology to try to understand the information priorities of other stakeholders within the company. The audit would not be directly related to security, but was aimed at learning about which information assets and information behaviors existed within various groups. Armed with this data, the project team could begin making recommendations about how to improve the partnership between the security team and organizational stakeholders based not only on the priorities of the CISO, but also on those of other groups. The Goal-Question-Metric (GQM) template for the information audit project is shown in Table 10-1.

Table 10-1. GQM Template for Information Audit Project

The information audit was conducted via a series of focus groups with various company departments, followed up by individual interviews with specific stakeholders and information users. The goal of the group and individual data gathering was twofold: to identify specific types and values (subjective or objective, as available) of information assets and to identify the informational activities that were most directly (usually negatively) impacted by the security requirements imposed by the CISO’s operations. The questions and conversations were not security-specific but instead asked the participants to talk about how information enabled their activities and what information problems would disrupt their business processes.

The result of the information audit was a great deal of data about how information was created, used, transferred, and shared within the organization. Since the questions were not framed in terms of security, and the presence of the consultant added an element of neutrality to the interactions, many of the participants felt encouraged to share broadly about the importance of information to their groups and individual jobs.

With the consultant’s help, the security team began to analyze the data and responses of the other stakeholder groups to identify patterns and opportunities for outreach. This was not always easy, because several measurement project members expressed frustration that the information had little to do with security and that the security team was about protecting IT systems and not analyzing other groups’ business operations. The CISO and the consultant attempted to use these observations as teachable moments, drawing comparisons between the project team’s frustration and the frustration experienced elsewhere in the company when people were told they had to do things that seemed to be the responsibility of the security team. The point was for each set of stakeholders to try to help the other understand more about concerns and priorities they may not have considered.

Assessing the Security Orientation of Participating Groups

One exercise conducted using the information audit data attempted to measure and map the company’s security orientations, defined as the priorities and concerns of other groups within the company, based on what those groups had said about information assets and behaviors in general. Group and individual participants were asked questions that did not specifically reference security, but were meant to identify issues that were security-related. These questions included the following:

![]() How bad would it be if a competitor was to get access to “X” information asset?

How bad would it be if a competitor was to get access to “X” information asset?

![]() What is more important: being able to customize information quickly or being sure that all information comes from a trusted source?

What is more important: being able to customize information quickly or being sure that all information comes from a trusted source?

![]() How negatively would your operations be affected if an application such as e-mail or Internet access went down for four hours?

How negatively would your operations be affected if an application such as e-mail or Internet access went down for four hours?

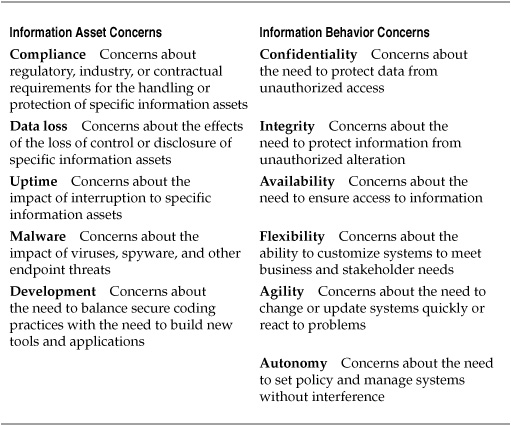

Participant responses to these questions were analyzed using a commercial qualitative data analysis tool to identify themes and patterns in the data. Categories were created based on the responses that framed general information responses into themes that the CISO’s team could begin to relate to security-specific functions and responsibilities. Two sets of categories were created:

![]() Information asset concerns These responses reflected concerns about the risks and requirements associated with types of information assets.

Information asset concerns These responses reflected concerns about the risks and requirements associated with types of information assets.

![]() Information behavior concerns These responses reflected concerns about the way information was used and how the participants needed to deal with information assets.

Information behavior concerns These responses reflected concerns about the way information was used and how the participants needed to deal with information assets.

For each category, several themes were developed from the response data. Table 10-2 shows a selection of these categorical subthemes.

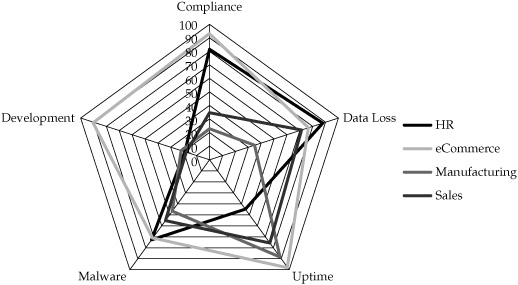

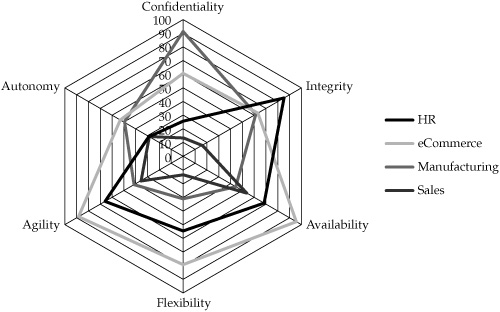

To analyze the security orientation of the groups participating in the information audit, the focus group and interview data was assessed to determine how often particular categories and subconcerns appeared in people’s discussions of their information environments and their responses to the questions about their information priorities. The metric used was a simple percentage of the number of participants who expressed a particular concern in either category. The results were used to construct security orientation “shapes” using radar charts for both categories. The orientation shapes for four of the groups participating in the project is shown in Figure 10-1, and the orientation shape for information behavior is shown in Figure 10-2.

Table 10-2. Security-Related Categories and Themes from Information Audit

Figure 10-1. Security orientation shape for information assets

Figure 10-2. Security orientation shape for information behaviors

Interpreting the Results and Developing Outreach Strategies

Analysis of the orientation charts visually showed differences between the orientations of the four groups, reflecting differences in priorities and concerns across the company. To be successful in partnering with other groups, the CISO would need to develop a greater understanding of these differences and adapt security operations accordingly.

Several immediate findings by the project team concerned how the CISO might make a better internal partner for the various departments:

![]() The eCommerce department expressed the broadest set of concerns, indicating that security played a role in their operations in many areas, from Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) compliance requirements, to the desire for flexibility and agility in their operations. In fact, it was the perceived lack of flexibility and agility that caused most of the complaints on the part of the department, as the security team was viewed as too inflexible regarding standards and policies around security.

The eCommerce department expressed the broadest set of concerns, indicating that security played a role in their operations in many areas, from Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) compliance requirements, to the desire for flexibility and agility in their operations. In fact, it was the perceived lack of flexibility and agility that caused most of the complaints on the part of the department, as the security team was viewed as too inflexible regarding standards and policies around security.

![]() The Manufacturing department had relatively few concerns regarding security. This group was content to let the security team drive policy and standards, so long as the manufacturing production systems experienced no downtime. One complaint indicated that manufacturing workers were asked to participate too much in security operations and would prefer to give up control and management of systems so long as they could count on the uptime of the systems they cared about.

The Manufacturing department had relatively few concerns regarding security. This group was content to let the security team drive policy and standards, so long as the manufacturing production systems experienced no downtime. One complaint indicated that manufacturing workers were asked to participate too much in security operations and would prefer to give up control and management of systems so long as they could count on the uptime of the systems they cared about.

![]() Opportunities existed for broad efforts in those areas where most or all of the groups participating identified similar concerns, such as data loss and integrity. In these cases, generally applicable standards and technologies could be pitched across groups. Conversely, the CISO could consider special approaches unique to the concerns of the eCommerce department concerning development standards and more focused coordination around exceptions and flexible configurations specific to that group.

Opportunities existed for broad efforts in those areas where most or all of the groups participating identified similar concerns, such as data loss and integrity. In these cases, generally applicable standards and technologies could be pitched across groups. Conversely, the CISO could consider special approaches unique to the concerns of the eCommerce department concerning development standards and more focused coordination around exceptions and flexible configurations specific to that group.

So what did this project measure? The data that was analyzed as part of the measurement project were the responses to the focus groups and interviews. These responses were real and observed things, empirical data, even if they could not be quantified directly. The categories and themes developed through analyzing the data were inductive and interpretive, based on the reasoning and judgments of the measurement project team with the help of the consultant. The combination of empirical data and interpretive analysis provided measurement insight into the attitudes and opinions of stakeholders that the CISO needed as partners in order to be successful and to make the company successful. The results of the project also helped the security operations group identify opportunities for further measurement projects, including more traditional security metrics that would be made more realistic as other departments bought into security as a company-wide priority.

As a final deliverable of the project, the CISO decided that the results needed to be shared outside the security team. He created a marketing strategy as part of his outreach program that made a point of showing other departments and stakeholders the different ways that security was viewed within the company and the conflicts that often resulted. Rather than keeping his new knowledge in a silo, where only the security team could benefit from the insights, the CISO took a “customer service” approach that encouraged people outside the security department to share their concerns and unique challenges with the security team and allowed the security team to respond in a more flexible and sensitive manner to competing ideas about what made for “good” security.

An Ethnography of Physical Security Practices

Physical security, even more than IT security, is a matter of intimate concern in today’s post-9/11 world. While we may talk about the threat of a “digital Pearl Harbor” or cyberwarfare as a new battleground, the loss of information does not compare with the visceral impact of a physical threat. And it is far more difficult in cases of physical security to discount the human aspect of the threat by throwing up new technologies (not that this works very well even in the case of information security, even though your security vendor will tell you otherwise). Physical security reminds us that protection exists in the context of a messy mix of physical space and human interactions that can affect everything from traditional IT security concerns to basic human feelings of fear, safety, and trust.

The following measurement project describes a joint attempt by an IT security group and a facilities security group to measure and understand their physical security challenges in the wake of an IT security incident. The incident involved an attack on the IT infrastructure of the company that was traced back to a rogue device that had been physically connected to the company’s internal network. The origin of the rogue device was never discovered, but in the course of the investigation it became apparent that the company suffered from physical security challenges that could have easily led to an external attacker being able to install the attack box in question. Most frustrating to both the facilities and the IT security groups was that the company had invested significant resources in a physical security awareness campaign, in response to several compliance requirements around securing facilities and physical assets. There were reviews undertaken as part of the joint security improvement effort, but the interest relevant to this chapter involved an experimental project that attempted to approach the problem from a different direction by conducting an ethnographic review of the organization’s physical security behaviors.

Ethnography in Practice

Ethnography is a qualitative research technique typically associated with anthropologists and sociologists that involves the detailed, immersive observations of a particular group or society and the interpretation of the behaviors and values of that are observed. The end goal is the development of both descriptions and explanations for the shared social practices of the group or society that can begin to describe the culture of the society. Culture may include rituals, religious beliefs, formalized social relationships, and many other aspects of how people come together to form complex and dynamic communities of practice. Ethnography is not just for academics. Industry has increasingly adopted ethnographic techniques to help companies understand how their customers use their products in daily settings or how they might react to new designs and features.

Ethnography can be painstaking work, requiring trained observers and enough time to develop familiarity with the environment being observed. Ethnography also has ethical dimensions, as the conduct of ethnographic field work often requires that observers build trust and be accepted to at least some degree into the group or society that they are observing. But from the perspective of empirical inquiry, ethnography is one of the foundations of qualitative research.

The goals of ethnographic studies are far different from the statistics and key performance indicators that provide diagnostic insight into an operational process. Ethnographers seek to understand how the entire complex system works, with human beings at the center of focus. Some practitioners of ethnography would take offense at the notion that they were measuring something, agreeing with those in the quantitative camp that what they are observing is not something that can be measured. But an ethnographer would not equate measurement with understanding, and would instead say that she were seeking a richer and more nuanced understanding of what she observed than any statistical assessment is capable of providing.

Observing Physical Security

Using outside expertise, a local professor who was a practicing ethnographic researcher, the company set up a security measurement project that would take a close look at the way physical security functioned within the company—closer than any previous study had attempted. The ethnographer would be partnered with several members of the facilities and IT security teams during a three-month period. (The company employees were assigned to the project part-time so as not to impact their daily jobs too much.) The ethnographer was given temporary employee status, assigned to the Director of Corporate Security, with full access to the company campus and resources. She would coordinate her activities with whichever member of the project team was “on duty” at the time.

The ethnographer’s task was to be a part of the company for the period of the assessment, but with a very specific role: She was to observe and explore how company employees engaged in physical security practices. Her participation in the company was open and announced, and employees were encouraged to approach her if they chose to do so. She was assigned a cubicle and was for all intents and purposes another employee. At the end of the project, she prepared a report of her analysis and findings. Table 10-3 shows the GQM template for the project.

Example Finding: The Competing Narratives of Tailgating

Ethnographic studies produce a great deal of data that can be used to reconstruct social and organizational practices as well as explore ways in which members of a group view and understand those practices and their particular activities. To demonstrate the findings that can emerge from an ethnographic study, I will focus on a single outcome of the physical security measurement project: the narratives, or stories, that emerged around “tailgating” practices.

All building entrances were controlled by electronic locks and badge readers that were centrally managed by the facilities security team, but tailgating was an acknowledged problem within the company. Tailgating occurred when an authorized employee badged into an entrance and then allowed others to enter without using an access badge. The rogue device had been installed under a vacant cubicle within 30 feet of an exterior door at the side of one building. When the original physical breach occurred, it was strongly suspected that the individual who had planted the attack box inside the corporate network perimeter had gained access to the facilities by tailgating into the building. Despite warning signs at every entrance warning against allowing people to enter without “badging in,” and training and awareness programs emphasizing that tailgating was dangerous and prohibited under the company’s security policy, tailgating was understood by the security teams to be a common practice.

Table 10-3. GQM Template for Physical Security Ethnographic Project

During the project, the ethnographer had many opportunities to tailgate into one of the five campus buildings, both alone and with her points of contact from the security teams. In addition to observing the process of tailgating by participating in it, the ethnographer would attempt to engage others in talking about tailgating, both at the time of a tailgating incident or in other social settings such as the cafeteria. She would explain her job at the company and, in a non-threatening and friendly manner, ask for permission to talk with the other individual about life at the company. While many employees chose not to respond (some even reported the incident to ensure that she was a legitimate employee), the ethnographer was able to collect interview data from nearly 30 employees over the duration of the project. When added to interviews with managers and security staff participating in the project, this data was then qualitatively analyzed using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS).

The tailgating interviews generated many stories from interview participants regarding why tailgating happens, why the person did or did not tailgate or allow others to do so, and why it was a dangerous practice. These stories had plots, characters, and events that formed a coherent personal explanation for some aspect of tailgating, and the storytellers used them to understand and rationalize their own behavior as well as to explain that behavior to others. Given the story nature of these explanations, the ethnographer recommended that the project team use narrative analysis to try to understand more about how tailgating functioned at the company. These stories, or narratives, could then be used to construct less soft, more formalized use cases and threat vectors about tailgating that could be better addressed by security operations.

Narrative analysis is a formal method used by researchers in the fields of public policy, organizational communications, and even more traditionally “hard” scientific disciplines such as medicine. Like other qualitative measurement techniques, narrative analysis tries to get at the nuanced and interpretive aspects of an issue that targeted statistical hypothesis testing cannot uncover. Narrative analysis is particularly useful when more than one narrative or story exists and the stories compete with one another. This happens a lot in public policy, when both sides of an issue can have different stories about what that issue represents. These stories serve to organize both facts and beliefs into an argument that can then compete with the facts and beliefs of the stories of others. Competing narratives also exist in business and industry, where facts exist in the context of organizational politics and competitive drivers. Narrative analysis does not reveal the “true” story of an issue, but it can help an organization gain visibility into competing stories and assess them rationally with the goal of overcoming conflicts.

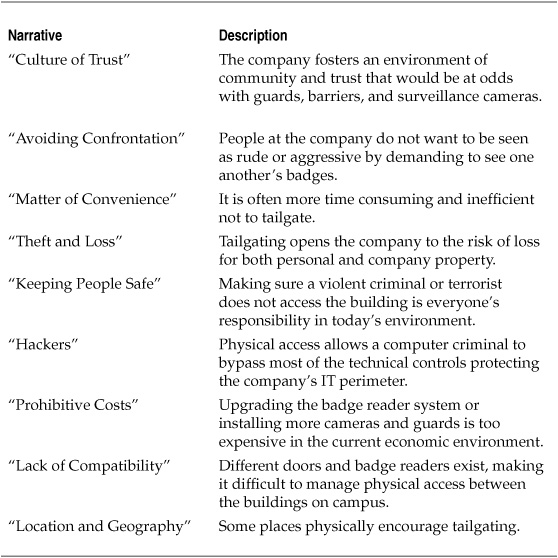

The analysis of project interview data revealed a number of stories that explained how tailgating functioned within the organization. These stories were constructed from the direct responses provided during interviews and discussions, categorized to identify common themes and patterns across the responses. Table 10-4 describes the nine major narratives that were identified.

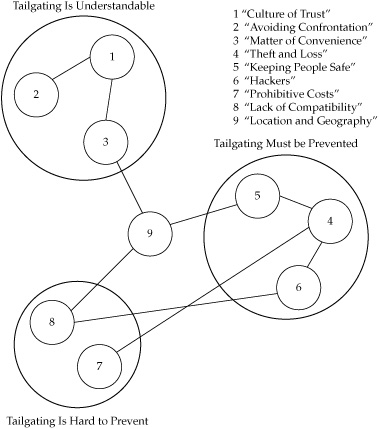

Examination of the narratives immediately revealed several different concerns and priorities among those providing responses. To further identify relationships between the narratives, the project team analyzed the data to show which narratives were common among interviews. In other words, narratives were connected when they would appear in the same interviews. As these connections were made, the narratives were then grouped into “metanarratives” that defined an overall rationalization around tailgating practices. These metanarratives included the following:

Table 10-4. Tailgating Narratives Identified During the Project

![]() Tailgating Is Understandable

Tailgating Is Understandable

![]() Tailgating Must be Prevented

Tailgating Must be Prevented

![]() Tailgating Is Hard to Prevent

Tailgating Is Hard to Prevent

Figure 10-3. Narrative network analysis of tailgating practices

Finally, the relationships among the stories, the metanarratives, and the interview data were rendered visually through a network analysis map, as shown in Figure 10-3. The larger circles represent metanarratives, the smaller circles are the specific narratives identified in the data, and the connecting lines represent the relationships between the narratives as described by the participants in the data collection.

Project Conclusions Regarding Tailgating Practices

The narrative networks in place within the organization showed three distinctive storylines about tailgating that were more or less at odds with one another. While the security teams strongly believed that tailgating had to be prevented, a storyline that compelled management to devote significant resources to posting signs and conducting training and awareness campaigns, the alternative story of resources and limited budgets preventing the installation of more effective preventative measures directly contradicted how important a problem tailgating actually was. The problem was serious enough to command some attention, but not serious enough to overcome the budget priorities that placed other problems higher on the list.

While many connections existed between the “must be prevented” and “hard to prevent” narratives, there was little or no connection between these and the stories of why tailgating was a common practice. The company encouraged trust and community but struggled with the negative effects of employees who therefore did not naturally suspect ill intentions of anyone on the campus. Even the physical geography of the campus played a role in encouraging tailgating in one instance, in which the cafeteria entrance directly faced an unguarded side entrance to another campus building. The result was pervasive tailgating as people carrying lunch trays found assistance in the form of helpful employees who would hold the door open for multiple people at a time.

To reiterate an earlier point, narrative and other qualitative forms of analysis do not offer statistical certainty, much less truth, about an issue. But they can help you reduce the uncertainty present in complex problem environments. Key findings that emerged from the physical security ethnography project, partly as a result of the narrative analysis of tailgating practices, included these:

![]() Physical security often meant very different things in practice to the members of the two security teams. Corporate security practices revolved around protecting lives and property, while IT security practices prioritized information assets. In both cases, each team tended to view the other as the simpler and more easily accomplished responsibility. Exposure to one another’s practices showed both teams the complexities of their operations and the impacts that their respective domains had upon each group’s mission.

Physical security often meant very different things in practice to the members of the two security teams. Corporate security practices revolved around protecting lives and property, while IT security practices prioritized information assets. In both cases, each team tended to view the other as the simpler and more easily accomplished responsibility. Exposure to one another’s practices showed both teams the complexities of their operations and the impacts that their respective domains had upon each group’s mission.

![]() Security managers on both sides (facilities and IT) expressed significant frustration at why problems such as tailgating continued despite the perception of significant efforts being undertaken to address the challenges. The project shed light not only on how the priorities and practices of everyday employees were the result of larger environmental issues, but also on the ways that the security teams’ practices and priorities were heavily influenced by complex organizational dynamics such as budgets and regulatory compliance.

Security managers on both sides (facilities and IT) expressed significant frustration at why problems such as tailgating continued despite the perception of significant efforts being undertaken to address the challenges. The project shed light not only on how the priorities and practices of everyday employees were the result of larger environmental issues, but also on the ways that the security teams’ practices and priorities were heavily influenced by complex organizational dynamics such as budgets and regulatory compliance.

![]() As with other such efforts to ask broad questions about an environment, the physical security ethnography project led to a number of ideas regarding other projects and measurement efforts. Many of these proposed follow-on projects were more targeted and quantitative in nature, designed to test and assess the general findings and insights that emerged from the qualitative measurement work.

As with other such efforts to ask broad questions about an environment, the physical security ethnography project led to a number of ideas regarding other projects and measurement efforts. Many of these proposed follow-on projects were more targeted and quantitative in nature, designed to test and assess the general findings and insights that emerged from the qualitative measurement work.

Summary

Measuring people, organizations, and culture in the context of IT security cannot be accomplished solely through the use of statistical methods or quantitative data, yet these aspects of our security operations must be explored and understood in order to make our security programs as effective as possible. The mantra of “people, process, and technology” is becoming more prevalent throughout the security industry as this realization sinks in, but measurement remains a challenge. A good example is the idea of risk tolerance, which is a function of organizational culture and individual personality that goes hand-in-hand with quantitative measures of financial or organizational risk based on empirical data.

This chapter reviewed two examples of security projects that relied heavily on formal qualitative approaches to conducting a security measurement project. Unlike the commonly accepted definition of qualitative security or risk assessment, which is often used as a catch-all phrase to describe projects that gauge opinion without rigorous standards of data collection or analysis, qualitative data analysis can be highly empirical and rigorously conducted, and it can require specialized training and expertise to perform. In both cases discussed here, outside consulting experience was engaged to complete the projects.

Information auditing is an organizational research technique from the fields of information management and information policy development. Traditionally used to help businesses and other organizations evaluate the uses and flows of their information assets, information auditing techniques were applied to security as part of an IT security outreach program in which a CISO was attempting to gather better data on stakeholder perceptions and practices around information use and the security of that information. By measuring the perceptions of other stakeholders within his company, the CISO was able to develop more effective strategies for promoting IT security as an enabler, with the IT security group as a partner rather than as an antagonistic and bureaucratic obstacle to the business.

Ethnography and narrative analysis are both qualitative approaches that are also used in many industries to assess organizational and social practices and relationships that can affect aspects of a business. Often used to evaluate product uses by consumers or to assess the effects of new product designs or features, ethnography involves the close observation of a group, organization, or society by researchers who are also participating in the group being observed. Ethnography was applied to a project seeking insight into the physical security practices of a company, including both facilities and IT security elements. One of the analyses conducted during the project involved gathering narratives, or stories, about how tailgating was practiced at the company. The narrative analysis provided evidence that competing priorities and environmental factors, and the stories with which these priorities and factors were associated, set up trade-offs and compromises that made it very difficult to prevent tailgating within the company. The resulting findings allowed the project team members to understand where their efforts could be impactful and where they were likely to be less effective.

Further Reading

Boje, D. Narrative Methods for Organizational & Communication Research. SAGE Publications, 2001.

Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. SAGE Publications, 2006.

Henczel, S. The Information Audit: A Practical Guide. K.G. Saur, 2001.

McBeth, M., et al. “The Science of Storytelling: Measuring Policy Beliefs in Greater Yellowstone.” Society and Natural Resources, 2005.

Merholz, P., et al. Subject to Change: Creating Great Products and Services for an Uncertain World. O’Reilly, 2008.

Orna, E. Information Strategy in Practice. Gower, 2004.