CHAPTER 11

The Security Improvement Program

Chapters 7–10 described a variety of security measurement projects, each developed using goals, questions, and metrics, and each designed to provide data and insights into the operational security of the organizations undertaking the projects. This project-centric approach to security is probably not that different from what you may be used to seeing in your own security operations—other than the specific goals for these projects, which all explicitly include measuring aspects and characteristics of IT security, and some of the methods used (not many in the security industry today are using qualitative narrative analysis as a means of understanding their security posture).

In most of the companies I visit during consulting engagements, security is managed on a project basis, whether the purpose of those projects are assessment, development, or implementation. We all understand security projects, but many of my clients complain that the project approach to security meets only some of their needs. Even organizations with strong capabilities around security and numerous projects in place for protecting systems and information find themselves in positions where risks and security incidents occur almost in spite of the organization’s efforts to understand and improve its posture. This only reinforces the fact that it is impossible to eliminate risk. Instead, we must learn to manage risk and to do that we need to measure it, and we must decide how much we are willing to accept and how much we can afford to mitigate.

Moving from Projects to Programs

Projects are bounded, focused, and finite efforts that have a defined beginning and end and a relatively unambiguous set of criteria for completion and success. When you set up a project, you know what you are trying to accomplish. Maybe it is an upgrade to the latest version of a particular operating system or software application. Or it’s the measurement of a particular aspect of your company’s security operations, as I’ve been writing about. Regardless of the purpose, the nature of projects is that they start, they progress, and they end as they have throughout the history of human activity. The central characteristic of project-centric approaches to problems is that projects (and the people that run them) are not as concerned with long-term memory or a sense of context. Project thinking is about the internal management of the project, about risks of staying on time and on budget, and about controlling the scope and resources involved in completing the project and moving on to other priorities.

Programs, on the other hand, are all about memory and context and include missions, charters, visions, and strategies. Programs are broad initiatives with the goal of coordinating a variety of often independent and distinct activities (such as separate projects) and allowing these different efforts and activities to contribute to larger goals that are greater than the results of any single project. Program-centric approaches to problems are not as tactical and do not have the same granular level of visibility into daily activities. Instead, program management concentrates on managing the overall direction of an enterprise, for which each individual project may be just a single step along the path.

If that path is to maintain some semblance of forward motion, rather than just meandering in circles, you must pay attention to how each project fits into a grand scheme. One easy example comes from the military: a single squad or platoon may be trained for a very specific purpose or mission, with minimal concern for and visibility into the campaign strategy, or the larger interoperation of the military forces. But ensuring that the unit gets where it needs to be to maximize its value will require the broad coordination of many other individual units just like it. I have seen a more security-specific example in recent years around the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), which has given many companies a program-level strategic goal (pass the next audit) that drives them to view their security projects (network segmentation, encryption strategy, policy development, and so on) in a more contextualized way.

Empirical research into the effects of IT governance and compliance programs shows that companies that have deliberately and formally instituted these programs have enjoyed increased bottom-line benefits such as increased revenue, increased customer satisfaction and retention, and improved cost and delivery of products and services. If you think about it, this makes intuitive sense. If you take the time and effort to figure out exactly what you are doing and why, chances are you will see where you can improve, and then you’ll begin to do those things better. As IT security grows into a mature industry function, more emphasis will be placed on how security management also drives profit, productivity, and operational effectiveness even in those areas that are not directly security related.

Managing Security Measurement with a Security Improvement Program

I began discussing the Security Improvement Program (SIP) in the context of Security Process Management (SPM) in Chapter 4. The SIP is designed to contextualize and guide security measurement so that the metrics and data that result from particular efforts at measuring security operations are used strategically as well as tactically. In Figure 4-3 of that chapter, the SIP is shown as a string of security measurement projects that are connected over time. In this model, each project is part of a knowledge loop in which the efforts and results of the previous project are explicitly used to inform and guide the next project. Like many of the ideas in this book, this is by no means a revolutionary concept and is a central tenet of organizational knowledge management. But after years of managing and consulting on security, I’ve found that capturing and reusing this knowledge is not typically prioritized in security organizations. I’ve seen repeated security engagements that stretch over years in which the connections between the engagements, even those that are similar or repeated efforts, are never explored. Instead, these projects are just one more box on a checklist of annual activities that need to be completed, an attitude that speaks as much to problems with security vendors as it does to the companies engaging them.

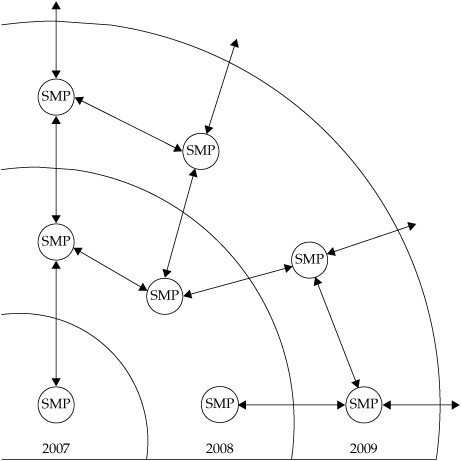

The Chapter 4 image of the SIP is overly simple in itself, focusing on the connections between repeated projects over time. A more accurate, but still very simple, expansion of this concept can be found in Figure 11-1, which shows the relationships among multiple projects during several years. In this visualization, a single security measurement project (SMP) conducted in 2007 leads to a repeat of the project in subsequent years, but it also spawns related projects that are specifically driven by the findings of the first. As more projects are added, the information flows between the projects increase, and the result begins to show the real complexity of holistic security practices. The most important aspects of the SIP concept are the arrows in the diagram, representing the knowledge relationships between individual projects. Projects are the way that things get done in an enterprise, but programs are the way that these efforts are made to represent something larger than the sum of the parts. In IT security measurement, SMPs can provide data and insights, but it is only through the programmatic approach of the SIP that these individual measurement efforts can be used to measure and manage security as a real business process.

Figure 11-1. Expanded SIP concept with multiple SMPs over several years

Governance of Security Measurement

What I am proposing in the SIP is a method of governance over your security metrics activities. Defining, managing, and improving the collaborations and connections between SMPs is different from operating those projects. Governance is about big picture management, and at an even larger level it is currently a hot-button topic in industry, as companies are increasingly being asked to be more accountable for the ways that they run their businesses by everyone from governments, to industry groups, to shareholders and customers. Governance is often associated with regulatory compliance and the management of public institutions or publicly traded corporations, but governance has a broader definition with regard to effective strategy development and execution. Nevertheless, as I noted earlier in this chapter, evidence shows that effective governance at a high level can have definite bottom-line impact on organizational effectiveness at all levels.

If you consider an individual SMP, such as those that I have described in the preceding chapters, you will find the goals, questions, and metrics that you use to define, limit, and bound the project. A main purpose of the GQM model is to create smaller, more manageable projects to avoid scope creep and to make the measurements and data involved in each project as meaningful and as specific as possible. In an SMP, you drill deep, but you do not focus broadly, which has advantages when you are exploring a security question in detail. But if you are trying to improve security across the complex and interrelated elements of enterprise-wide security, this focus on the specific can become a disadvantage if you have not thought about how you will pull all those results together. You will end up with a lot of interesting specialist data and information, but not much knowledge about what it means for managing organizational risks as a whole. The resulting uncertainties that exist between projects and measurement can produce significant risks. Identifying a lot of dots is not the same thing as connecting those dots to create a meaningful picture. Worse, if all you know are your own dots, you may make the mistake of assuming that you have the complete picture when you really are taking a parochial view. Governance is about getting high enough above the details to see the patterns, risks, and opportunities that are not visible at the lower levels of detail.

Governance, at heart, is about strategy and does not apply to any single thing. As you implement your security metrics program, you need to assess not only how you are measuring those aspects of security that you feel are important, but also how you decided what was important and how those decisions fit into your overall security strategy. I can’t tell you how to prioritize your particular challenges or how to decide what is important to your organization beyond the most basic common sense advice. What I can tell you is that governance is about defining and documenting those decisions so that if anyone does ask, you aren’t left looking like a deer in the headlights.

Defining what constitutes risk and security within an organization is one of those things that often may seem so basic that many people do not even bother to do it. Many security managers have been unable to give me a specific answer to the question, What is your risk? Of course, they have a lot of ideas about problems or challenges that they face, but not enough formal definition or analysis of those problems and challenges to begin to measure them to any degree of precision. The purpose of implementing a formal SIP in support of your security metrics program is to provide the necessary governance structures to help guarantee that the SMPs you undertake will support more than just the tactical goals and questions that make up the projects.

The SIP: It’s Still about the Data

If your SMPs were about collecting and analyzing data in support of the goals and questions that you established for each project, then the SIP is about making that data more useful to more people in more contexts. IT security metrics have at least two values: The first value is to the immediate measurement project that needs the data to meet a project goal. The second value is to the project teams, managers, and others who will benefit from the metrics data later when they replicate the project, conduct a related project, or seek to understand broader security issues by examining case studies and historical evidence.

Replicated or Repeated Projects

In many cases, SMPs are not one-time projects, but are repeated on a regular basis, such as in the case of vulnerability or risk assessments, monthly or quarterly reviews, or decision support projects around budget or staffing. You would think that, of all the examples here, these types of repeated projects would benefit from governance structures of the sort proposed by the SIP. After all, these projects are expected and scheduled and often are conducted by the same people over some time period.

Unfortunately, even these projects are all too often treated as stand-alone efforts, more or less disconnected from what went before or what may come in the future. Part of the problem can be a checklist approach to security, in which a list of annual activities exists, based either on a formal compliance requirement or on various definitions of best practice that mandate certain activities will be completed regularly. When projects are conducted for these reasons, the motivation to understand what the project actually accomplished (knowing what tasks have been completed and the resulting changes, as opposed to completing a task and checking off the box) is far less than if the project were part of a security improvement strategy. I’ve seen many examples of repeated security assessments in which the final deliverable each time is virtually the same as the previous versions, indicating that the real security benefit was the ability to say an assessment had been completed.

A SIP approach, on the other hand, would focus not on the immediate findings of any single project, but on the attempt to determine whether or not security was changing as a result of all SMP efforts. By measuring the lack of progress in correcting or improving security problems among projects, the SIP can provide valuable insight into the real functions of your security operations.

Follow-on or Related Projects

An SMP, particularly one that is bounded and specific, will often lead to questions that are obvious, but that are not addressed directly by the metrics and data that emerge from that particular SMP effort. Several examples of this sort of follow-on project opportunity existed in the projects discussed in earlier chapters. In these situations, two capabilities need to be in place if the opportunity is to be effectively addressed:

![]() A capability for driving the questions and requirements from the first SMP into a new, separate SMP

A capability for driving the questions and requirements from the first SMP into a new, separate SMP

![]() A capability for aligning and mapping the results of the related SMP among projects

A capability for aligning and mapping the results of the related SMP among projects

The need for effective measurement governance in these situations is particularly important, because the projects in question may cross functional or organizational boundaries. If a penetration test, for instance, discovered widespread availability of intellectual property on user laptops or workstations, then an obvious follow-on question might be this: What process deficiencies were contributing to this lack of protection of sensitive information? The network security team, however, might have no authority or ability to drive a security measurement project through other business units to determine why this information was so prevalent. In these types of situations, a dedicated SIP capability with appropriate management support could step in to ensure that the appropriate actions were taken.

Historical or Exploratory Projects

It has been said that history does not repeat itself, but it rhymes. In the companies with which I have worked for more than two decades, new initiatives are always being designed to improve this or that element of operations. If you stay with one organization long enough, you will invariably begin to come across initiatives that make you ask, “Didn’t we do this five years ago, when it was called Project X?” The same holds true for security. As technologies change and evolve, it is as if we come back around full-circle to challenges and solutions that are eerily reminiscent of things we have seen before. Sometimes the repetition is direct as staff turns over and old ideas are introduced as new initiatives by people who don’t realize that their ideas have already been proposed and implemented. Or the goals and ideas are new, but past activities can offer instruction on risks and benefits that can make an impact on the new efforts. In both cases, without easy access to the data and results of previous attempts, progress can move very slowly.

A deliberate application of SIP principles can provide institutional memory and a repository of data that can help security grow more agile by reusing and recycling knowledge across projects and over time. From general reviews of past efforts prior to beginning any new project, to exploring untapped areas of security improvement, a well-documented and deployed SIP can offer benefits in this regard. At a more general level, the SIP can also help to break down silos between security functions and project teams and encourage more active collaboration and experience-sharing both within the security group and across the entire organization. Developing such institutional knowledge and awareness is at the core of corporate improvement research and many initiatives around quality and sustainable growth across many industries. I cover some of this research in Chapter 12.

Requirements for a SIP

By following several key principles when setting up an effective SIP to govern and support security measurement activities, you’ll help ensure that the efforts you make will actually improve your organization’s security rather than simply collect data about it. Many of these principles are common sense necessities for any organized effort, but with careful thought, you can make them specific to the needs and challenges of your metrics program.

The SIP concept operates on three core principles:

![]() Documentation of security measurement projects and activities

Documentation of security measurement projects and activities

![]() Sharing of security measurement results

Sharing of security measurement results

![]() Collaboration between projects and over time

Collaboration between projects and over time

Before You Begin

As with other components of the SPM framework, you should explore several specific considerations prior to beginning the work. Your SIP activities will benefit from your understanding of how these considerations affect your initiatives and program before you start implementing them.

Management Support and Sponsorship

As with just about any security initiative—in reality or on paper—management support is a key issue. If management does not directly support your efforts, your prospects for long-term success are limited. Every high-level framework you might consider applying to your security program—from ISO 27000, to Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT), to Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL)—emphasizes management support and commitment as a core component of success. Yet such commitment can be hard to come by, and it can be just as easily lost to other priorities.

My general advice on management support is to trade ambition for stability. I would rather have director or senior-manager support of a security initiative, based on regular conversations and involvement, than a memo from the CIO I have met once promising that the company will make security a top-five priority (after which I hear nothing until the next annual memo). Even if the support of middle management limits the scope of what I may accomplish immediately, it makes it far more likely that I will be able to show the continuous improvement and sometimes exploratory leaps in insight that can eventually demonstrate value to that CIO in the financial and business terms that will get his or her attention. I recommend that you find a sponsor at the highest level possible who will actively and regularly support the SIP. This will often be the CISO, but it can be a lower level manager or even a project lead. Many improvement programs start with the efforts of a single individual.

The great thing about an effective SIP is that it can function as narrowly or as broadly as is necessary so long as the three core principles are met. As the SIP grows, the ability to adhere to these principles can grow quite complex, of course, but for most security metrics programs, implementing a SIP can be quite manageable for a security operations group. Setting up documentation, sharing, and collaboration practices does require a commitment to the sort of program-level thinking and activities that the SIP represents.

Staffing and Resources to Support the SIP

Making the SIP effective will require that it be appropriately supported in terms of staff and resources, although the requirements for such support do not need to be onerous. Much of what is accomplished in the SIP is about making sure that information is made available to a larger audience. This takes organization, documentation, and a focus on actually doing the sharing rather than simply talking about it. Today’s corporate environments are embracing collaboration and information sharing to an unprecedented degree, making these goals in the development of the program easier to accomplish.

Staffing and resource allocation for the SIP is very much dependent on the structure of the organization, the size and makeup of the security group, and the skills available among existing staff. It is unlikely, at least in the beginning, that a dedicated employee will be available for managing SIP-related activities. But at least one individual should be responsible for ensuring that the results of specific measurement projects are properly documented and stored. Just as the assignment of project leads ensures central responsibility for the activities around completing a project, the security improvement program lead will be responsible for ensuring that individual projects are coordinated, that the appropriate documentation is generated and stored for future use, and that reporting on the results of the program is accomplished at regular intervals.

One strategy for developing SIP staffing is to approach your company’s existing knowledge management (KM) team, if one is available. These groups already understand the importance of information sharing as well as techniques and tools that may be in place to facilitate such sharing. If your organization does not have a formal KM function, you should explore how company information is disseminated in other ways, such as via content management systems or the corporate intranet. The groups that manage these infrastructures can also be important sources of advice on how to create, store, and manage your SIP elements.

Definitions of SIP Elements and Objectives

Just as the security measurement projects you create depend on definitions and objectives to be tactically successful, the SIP requires that you make some formal efforts to understand what it is you are trying to accomplish strategically. These definitions will provide the frame story and the context within which your measurement project activities will align and contribute toward the larger goals of the program. In some ways, SIP-level definitions parallel the GQM model used to set up an SMP. But instead of answering specific questions about security by collecting and analyzing data, the SIP will attempt to determine how well those answers are supporting the larger security strategy across projects.

Defining Security If we parse out the term security improvement program, we must formally define several elements if we are to understand what we are trying to accomplish. I’ve already defined program: a systematic approach to managing multiple projects and initiatives so that the results of these activities are documented, shared, and successfully leveraged across different teams and efforts over time. But what about the other two elements? Let’s begin with security. How is it defined? When you talk about security, what do you mean? Security is one of those terms that is used so often and in so many contexts that it has begun to lose any specific meaning. Security is simply what we do. If you are responsible for a DMZ, security is your assurance that no one can penetrate that perimeter. If you are the HR specialist writing the company’s acceptable use policy for the network, security may be the assurance that your employees will not use the network for prohibited activities and, if they do, it can entail your ability to take action and protect the company from liability.

Local definitions are just a fact of life in the security world, which can become highly specialized, but it makes it difficult to measure security outside of one’s own area. As you set up a SIP to manage and coordinate projects that may originate in a variety of functional areas, you’ll find it increasingly necessary to define precisely what you mean by security. In the insider threat case study described later in the chapter, security is formally defined as the likelihood that a company employee will be the root cause of a security incident, whether intentional or otherwise. This definition of security allows a SIP to be put into place that will coordinate and manage the efforts of multiple SMPs that focus on preventing internal security incidents. Whether the measurement project involves people, processes, or technologies becomes secondary to the question of whether the project measures the capability of someone inside the company to become a security problem.

Defining Improvement You also need to define the concept of improvement. Security managers often talk of security as more of a zero-sum game, in which either there is a security incident (failure) or there is not (success). This binary view of security has done a lot of damage to security programs by discouraging more nuanced approaches to protection.

By way of example, I have been involved in many vulnerability assessments. One frequent argument during these assessments arises when the team is able to use a vulnerability to gain root access to a system, completely compromising it. A common temptation is to play up the fact that the security on that system allowed complete compromise, regardless of whether or not the system actually had any important information on it or was in a position to damage the organization conducting the assessment. In many cases, the nature of vulnerability testing is such that the testers have no way of knowing the actual impact of a particular vulnerability, as they function at a definitional level of security that deals only with whether or not the configuration of the system allows it to be compromised. As a result, improvement can be measured only at the level of technical vulnerabilities on individual systems, rather than regarding actual business impact. This tends to create a myopic and incomplete perception of security. Using this criteria, security remains reactive and backward-looking and the organization has little opportunity to get ahead of the problem.

Definitions of improvement must be considered in a wider context when constructing your SIP objectives. Improvement is not just about correcting existing problems, but identifying the root causes of those problems so that you can reduce the chance that they will be repeated in different forms. Improvement is also about establishing the baselines and SIP-level metrics that allow you to determine whether you are making improvement process and by what degree. In the case study that follows later in the chapter, security improvements regarding insider threats were defined using several different baselines that allowed the organization to determine whether or not progress was being made.

Documenting Your Security Measurement Projects

The first core principle of building an effective SIP revolves around the need to have reliable, documented information available on all the security measurement activities that you conduct. This is a challenge, particularly since most security programs do not have formal documentation for many basic operational activities, much less for the various projects and implementations that are done in support of those operations. The reasons for this lack of documentation can range from simple lack of time to the perception that documentation is nothing but a bureaucratic waste of time. But whatever the excuse, a lack of sufficient documentation regarding your security program and activities indicates a lack of maturity in those activities.

Supporting Capability Maturity

Capability maturity as a concept has developed primarily out of defense research initiatives. Capability maturity has been applied both to military operations as well as to the development of systems and software, and many models and frameworks exist for discussing capabilities maturity. The concept is to move from ad hoc, unmanaged, and conflicting processes and activities, which are characterized as immature, to increasingly mature processes and activities that are standardized, formally managed and measured, and synchronized through collaboration and coordination. The level of maturity exhibited by an organization or function defines how well it can learn from its own efforts and how effectively it can apply those lessons to continuous improvement and progress.

The most well-known example from an IT perspective is probably the Capability Maturity Model and its subsequent versions developed at the Software Engineering Institute, a U.S. Department of Defense funded institution run by Carnegie Mellon University. The Software Engineering Institute’s Capability Maturity Model has also been adapted by others, including as a component of the Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT) framework developed by Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) for IT governance. Defense institutions have also applied capability maturity concepts to the operation of command and control systems for military and intelligence activities.

But capabilities maturity is not just about coordinating projects or military campaigns. The organization of knowledge and scientific progress is also a measure of capabilities maturity and has been a foundation of scientific progress for centuries. The field of library and information science (LIS), for example, has a primary mission of organizing and disseminating information to ensure that entire communities and societies can increase their effectiveness and growth.

The Basics of SMP Documentation

Most security projects are documented to some degree, although measurement projects will perhaps demand more contextualized information than security upgrades or the implementation of a new system. Fortunately, if you are building GQM templates for your measurement projects, you will already have a basic documentation component completed. GQM forces you to define your scope and purpose and to develop formal mechanisms for gathering and analyzing data. At the very least, the GQM template will represent a record of a project’s purpose and criteria for success.

As an SMP progresses, more opportunities for documenting the progress of the project can come from many different sources:

![]() Project team e-mails and meeting notes

Project team e-mails and meeting notes

![]() Documents, memos, and project presentations

Documents, memos, and project presentations

![]() Analysis and project findings

Analysis and project findings

![]() Feedback from stakeholders and project team members

Feedback from stakeholders and project team members

You should consider up front how the project team will manage and collect the data necessary to document the SMP sufficiently, as this will help prevent your having to reconstruct that documentation after the fact from people’s memories and other less-reliable sources. Basic documentation components of the SIP might include the following:

![]() A SIP overview template to identify, describe, and define the objectives of the improvement program

A SIP overview template to identify, describe, and define the objectives of the improvement program

![]() A project catalog to track the goals, questions, and metrics associated with individual SMPs

A project catalog to track the goals, questions, and metrics associated with individual SMPs

![]() A metrics catalog to document the kinds and types of measurement activities you have undertaken

A metrics catalog to document the kinds and types of measurement activities you have undertaken

![]() An analysis catalog that contains findings, lessons learned, and opportunities and challenges that might prove useful to other measurement project teams

An analysis catalog that contains findings, lessons learned, and opportunities and challenges that might prove useful to other measurement project teams

![]() Project journals and other knowledge-capture tools to facilitate the collection of project-specific information not contained in catalogs or final project reports

Project journals and other knowledge-capture tools to facilitate the collection of project-specific information not contained in catalogs or final project reports

Sharing Your Security Measurement Results

After projects have been documented, information collected during and as a result of the project must be made available to appropriate audiences. Given the sensitivity of specific security-related data, it may not be appropriate simply to throw the results of the vulnerability assessment on to the company intranet. But there is also no value in hiding or compartmentalizing project information that could actually support other security measurement activities.

Considerations for Sharing Measurement Data

At minimum, general information about projects, metrics, analyses, and lessons learned should be made widely available as part of the SIP. I would even recommend sharing this information beyond the security team. Visibility into security operations can help non-security–related stakeholders better understand how they can benefit from as well as support the organization’s information protection strategies. By creating general catalog data of the type of security work being done, you can ensure that participation in the security process can be achieved without exposing details that might pose an additional threat to IT systems. Increased transparency can also help other stakeholders with responsibilities for compliance and corporate risk management to engage with the security team more easily. The bottom line is that sharing security measurement results does not mean sharing them only with the security function of the organization.

No matter how you choose to share your metrics results, some considerations will usually apply:

![]() Where will the documents be stored?

Where will the documents be stored?

![]() How will documents be organized? Will they be indexed and searchable?

How will documents be organized? Will they be indexed and searchable?

![]() What access controls will be placed on the documents? What approval process for access will need to be developed?

What access controls will be placed on the documents? What approval process for access will need to be developed?

![]() How long will documents be stored and maintained? Will they fall under the corporate records retention schedule and will they be archived?

How long will documents be stored and maintained? Will they fall under the corporate records retention schedule and will they be archived?

![]() How will documents be traced and their authenticity established?

How will documents be traced and their authenticity established?

Tools for Document and Information Sharing

Document storage and management falls under the larger topic of enterprise content management, which is outside the scope of this book. Most companies today employ enterprise-content management systems of varying levels of sophistication, ranging from static web pages and file shares up through full-blown enterprise content-management suites that also include functionality for collaboration and workflow management. The tools you choose for managing documents are less important than your commitment to manage them. Simple solutions using a dedicated e-mail alias combined with file sharing can serve to provide an adequate platform for sharing and disseminating SMP content so long as that content is there.

Collaborating Across Projects and Over Time

Like document management, collaboration has become an industry unto itself, with a variety of techniques and tools that are themselves the subjects of implementation frameworks and trade books. A lot of research in recent years has focused on how to foster and encourage more collaboration in the workplace, and while technology can play an important role in encouraging collaborative behavior, most agree that technology cannot create a collaborative environment. Collaboration is, at heart, a social function and requires that users be encouraged to share and explore with one another (and trained on how to do so effectively and appropriately) to be effective. The point is less about whether you choose to collaborate on security projects by e-mail, wiki, or collaborative working environment systems that incorporate all of these and more into one software solution. Instead, you should be focusing on getting your organization to embrace the value of creating, disseminating, and exchanging information and content.

Fostering a Collaborative Security Measurement Environment

Before technology even comes into the picture, you can encourage more collaboration within your SIP in several ways. Remember that the point of the SIP is to increase the awareness of specific measurement projects and activities, to include project teams that may be conducting similar projects over time and to make new projects more meaningful and more effective. In academic and industry research environments, where the goal is to increase and improve knowledge about specific issues or questions, these principles are deeply ingrained. I’ve suggested earlier in the book that the research program metaphor can add benefit to a security metrics program. In the SIP, the primary task is to synthesize and share the knowledge from a variety of individual measurement efforts, and a research approach can prove doubly valuable.

Collaboration can be encouraged in several ways:

![]() Management support Management should visibly and explicitly support collaboration and provide encouragement not only in words, but also by providing collaboration tools and training employees in how to share information more effectively.

Management support Management should visibly and explicitly support collaboration and provide encouragement not only in words, but also by providing collaboration tools and training employees in how to share information more effectively.

![]() Open documentation The document repositories and catalogs I mentioned have a much greater chance of being used by others when they are easy to access. Working with your company’s content management team can help identify ways that you can safely post and advertise your security metrics data.

Open documentation The document repositories and catalogs I mentioned have a much greater chance of being used by others when they are easy to access. Working with your company’s content management team can help identify ways that you can safely post and advertise your security metrics data.

![]() “Silo busting” Taking a proactive stance on reaching out to other individuals and teams, both within IT security and elsewhere in the organization, can make a big impact on removing barriers to collaboration.

“Silo busting” Taking a proactive stance on reaching out to other individuals and teams, both within IT security and elsewhere in the organization, can make a big impact on removing barriers to collaboration.

![]() Making collaboration natural Adding collaboration to everyday activities such as meeting agendas and project plans can be useful for keeping the need to create and share content at the forefront during everyday activities.

Making collaboration natural Adding collaboration to everyday activities such as meeting agendas and project plans can be useful for keeping the need to create and share content at the forefront during everyday activities.

Tools for Collaboration

We are fortunate in that we live and work in an environment that sees new collaboration tools appear every day. A great selection of open source and freeware tools are also available, and they can be used to build or supplement your SIP collaboration needs. A full list of available tools is not possible here, but you likely already have the following basics available within your environment that can be used to increase your collaboration capabilities:

![]() Instant communications E-mail and instant messaging (IM) have become ubiquitous in most corporate environments (and if you have an IT security program, you probably have corporate e-mail and IM). If you use these tools as a primary means of collaboration, be sure to consider how you will archive and share the content that you create so that it remains available.

Instant communications E-mail and instant messaging (IM) have become ubiquitous in most corporate environments (and if you have an IT security program, you probably have corporate e-mail and IM). If you use these tools as a primary means of collaboration, be sure to consider how you will archive and share the content that you create so that it remains available.

![]() Web logs and video sharing Some enterprises have begun to encourage employees to use web logs, or blogs, and even shared video to communicate, create content, and share experiences through collaboration. If your organization has an internal capability for blogging, consider setting up a security metrics blog for one or more audiences to share your metrics results.

Web logs and video sharing Some enterprises have begun to encourage employees to use web logs, or blogs, and even shared video to communicate, create content, and share experiences through collaboration. If your organization has an internal capability for blogging, consider setting up a security metrics blog for one or more audiences to share your metrics results.

![]() Brainstorming and mind mapping Software for documenting the relationships between concepts and organizing projects and concepts has become increasingly sophisticated and robust, allowing you to explore central concepts through a hierarchy of related ideas.

Brainstorming and mind mapping Software for documenting the relationships between concepts and organizing projects and concepts has become increasingly sophisticated and robust, allowing you to explore central concepts through a hierarchy of related ideas.

![]() Wikis and peer review systems These tools allow people to collaborate by making it much easier for individuals to create, edit, and review the work of others while ensuring version control and the ability to track changes and progress over time.

Wikis and peer review systems These tools allow people to collaborate by making it much easier for individuals to create, edit, and review the work of others while ensuring version control and the ability to track changes and progress over time.

Measuring the SIP

The SIP is subject to measurement and evaluation just like any other aspect of your security, and you should be considering ways to assess the effectiveness of your SIP-related actions. You can view SIP performance in two ways: how well those activities related to the improvement program are functioning, and the resulting effects on your security as a whole.

Security Improvement Is Habit Forming

Security will not magically improve on its own, even if you have an arsenal of techniques and tools available and at your disposal. Like losing weight, quitting smoking, or any other fundamental behavioral change, improvement is achieved only by replacing old habits with new ones. Security improvement is about building new organizational habits on a day-to-day basis. The best places to start, then, are those day-to-day activities that make up our security programs. If the SIP is a “big picture” process that is considered only at the end of projects, it will be less effective than if it is embedded in daily activities such as staff meetings, project plans, and performance reviews. The more people are responsible for contributing to the SIP by incorporating documentation and collaboration into their individual security activities and projects, the more successful you will be in improving security from the ground up over time.

Is the SIP Working?

Measuring the effectiveness of the SIP involves more specific and program-oriented metrics. The object of measurement here is how often the SIP is used and in what capacity. The point of improvement program metrics is to ascertain whether or not the daily activities and habits that contribute to long-term security improvement are being accomplished. Examples of these metrics include the following:

![]() How many SMPs (ratio) include a formal review of previous, related measurement projects?

How many SMPs (ratio) include a formal review of previous, related measurement projects?

![]() How many SMPs (number or ratio) have been documented and made available as content to other groups?

How many SMPs (number or ratio) have been documented and made available as content to other groups?

![]() How often are SIP-related activities or metrics included in meeting agendas? In project plans? In management briefings?

How often are SIP-related activities or metrics included in meeting agendas? In project plans? In management briefings?

![]() How many employees have security improvement objectives formally included in their job descriptions or performance plans?

How many employees have security improvement objectives formally included in their job descriptions or performance plans?

Is Security Improving?

Of course, the main purpose for implementing the SIP is to improve security by coordinating the efforts of multiple projects and initiatives over time. To do this, metrics must be in place that can be used to judge whether or not the SIP is having the intended and desired effect. If the SIP is properly designed and the concepts of both security and improvement appropriately defined, then the baselines needed to determine whether security is indeed improving security should already be in place.

Security improvement can be measured only over time. This emphasizes the importance of making sure that SIP activities are consistent and conducted regularly so that a store of longitudinal data can be built and correlations made between projects. If previous project results are not revisited and reviewed, and then measured against the established baseline to determine whether they had an effect, then only static, single-point inferences will ever be achievable. Ongoing comparative program review requires commitment and repeated effort; this is not easy to accomplish in any organization, but it is at the heart of true, continuous improvement of security.

While specific metrics are more difficult to illustrate, given the fact that baselines depend on the needs and measurements of your unique program, you should be looking for the following types of evidence that the SIP (and by extension your SMPs) are having an effect:

![]() Is the baseline changing over time? Is the quality, quantity, or character of your measured security activities different after each successive project? Is the difference significant (not just a product of random chance or noise)?

Is the baseline changing over time? Is the quality, quantity, or character of your measured security activities different after each successive project? Is the difference significant (not just a product of random chance or noise)?

![]() Are more projects being added, reviewed, and incorporated into the SIP? Are the measurement activities in which you are engaging leading to repeated activities as well as inspiring new activities that take your security measurement farther and provide more insights?

Are more projects being added, reviewed, and incorporated into the SIP? Are the measurement activities in which you are engaging leading to repeated activities as well as inspiring new activities that take your security measurement farther and provide more insights?

![]() Is security becoming more visible within your organization? Are silos being overcome and security value being better articulated to other business stakeholders?

Is security becoming more visible within your organization? Are silos being overcome and security value being better articulated to other business stakeholders?

![]() Do your security measurement activities reduce your uncertainty, and by extension your risk? Are the results of your security metrics and your SIP allowing you to make more informed decisions (including decisions in which security traditionally did not participate)?

Do your security measurement activities reduce your uncertainty, and by extension your risk? Are the results of your security metrics and your SIP allowing you to make more informed decisions (including decisions in which security traditionally did not participate)?

Case Study: A SIP for Insider Threat Measurement

To demonstrate how a SIP may be constructed, consider the case of ACME Inc., a company that became concerned with its insider threat posture after experiencing a potentially damaging security incident. Following the termination of an employee with the IT department, the company received reports that the individual was approaching the firm’s competitors with proprietary information and intellectual property. The individual was hoping to sell the information or use it to find a new job.

An investigation into the incident revealed that the former employee was offering very sensitive information that had not been part of his job, and some of the information dated from after his termination. It turned out that the employee still had access to the company’s network and was using that access to break into company systems and steal data. While the employee’s official access had been discontinued upon termination, he had used guest accounts to access the network and had been able to find vulnerable internal systems that he compromised and used to steal company data. The investigation also revealed that the employee had been motivated in part because of financial debts incurred through an addiction to gambling. This gambling problem had also been a root cause of the performance issues that had resulted in the employee being fired, which had motivated the individual to “get some payback” from the company.

The investigation of the security incident caused the company to revisit its security operations on a number of levels, and several security measurement projects were developed and proposed:

![]() Identifying internal network vulnerabilities that could allow access to the network and the theft of proprietary data or other problems

Identifying internal network vulnerabilities that could allow access to the network and the theft of proprietary data or other problems

![]() Revisiting the security policy architecture and compliance requirements for protecting the organization’s data

Revisiting the security policy architecture and compliance requirements for protecting the organization’s data

![]() Assessing security awareness and the internal protective culture of the company to build better training programs

Assessing security awareness and the internal protective culture of the company to build better training programs

![]() Proposing projects to assess other vectors of data loss, such as e-mail, and to measure the effectiveness and use of the company’s employee assistance program, which might have helped mitigate the employee’s gambling problem before it became acute

Proposing projects to assess other vectors of data loss, such as e-mail, and to measure the effectiveness and use of the company’s employee assistance program, which might have helped mitigate the employee’s gambling problem before it became acute

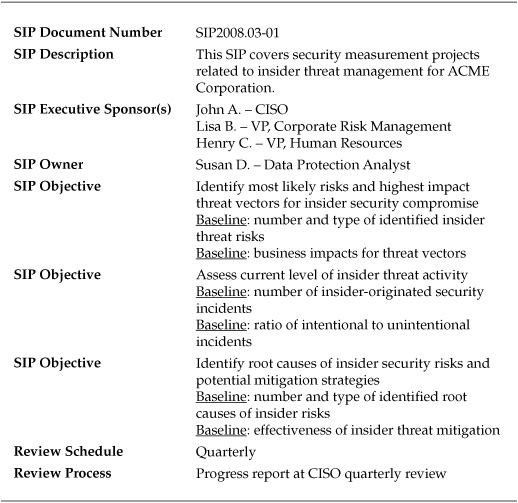

Given the interrelated nature of these SMP activities, the company also developed a SIP to coordinate the results and to ensure that a holistic and comprehensive approach was taken to combating future insider threats. The SIP was assigned sponsors and an owner and was used strategically to manage the various insider threat projects involved. The objective of the SIP was to ensure that the component initiatives and projects maintained their context and could be used to build organizational knowledge and experience. A SIP overview document was developed and a storage repository set up through a protected wiki so that various project teams could share ideas and post their results. The SIP overview document for the program is shown in Table 11-1.

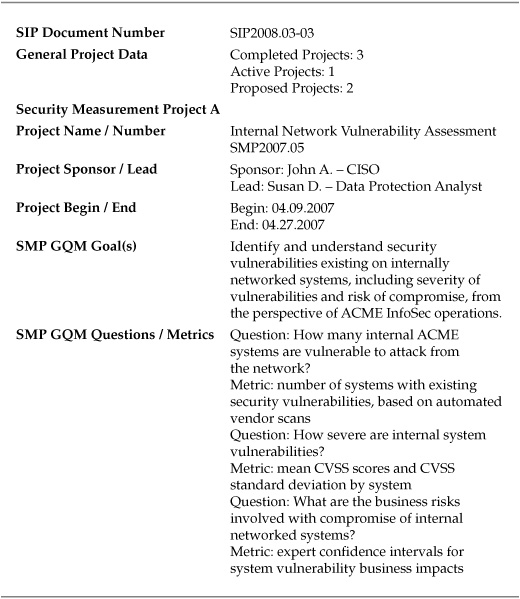

Table 11-1. SIP Overview Document for ACME Corporation Insider Threat Improvement Program

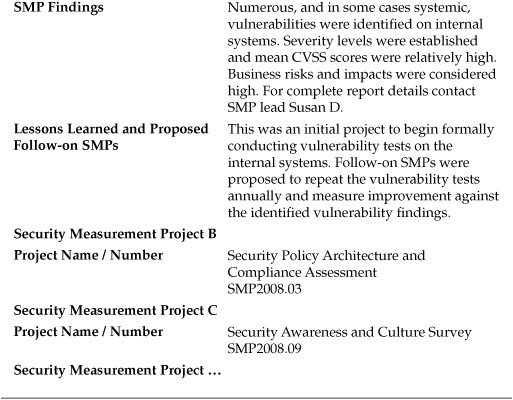

In addition to the overview document, the SIP provided catalogs of various projects, metrics, and findings that were also communicated over the wiki. Updates on the individual SMPs were provided through normal project management and reporting channels, and the SIP owner communicated the program-level results and findings to the CISO during quarterly reviews. The relationship between projects was captured in a detailed project catalog document, shown in part in Table 11-2.

Table 11-2. SIP Project Catalog for ACME Corporation Insider Threat Improvement Program

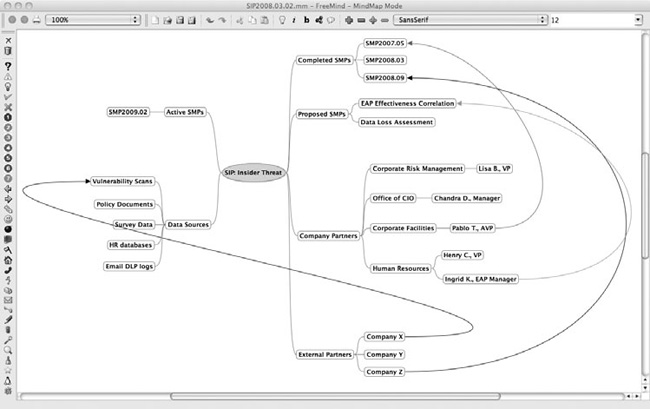

The SIP owner also found it useful to maintain a visual map of the relationships and connections among projects. Using an open source mind-mapping application, FreeMind, she was able to build graphical diagrams of the various projects and their status, components, sponsors, and interconnections. An example of such a diagram in FreeMind is shown in Figure 11-2.

The goal of the SIP, both in the case of ACME and in general, is to create and guide the organizational habits that keep an objective present and visible in the face of complex activity. The concept is not new or particularly revolutionary, but developing a coordination program to help manage projects and encourage cross-functional documentation and collaboration is absolutely necessary in order to transform your security into an effective business process.

Of course, there is always a level of coordination in any security organization, and no project is ever conducted completely in a vacuum. But in nearly every security environment I have experienced, the level of cross-project collaboration and documentation is less than optimal. In most cases, companies struggle with effectively documenting and managing single projects and initiatives, let alone understanding and identifying the ways that these projects interrelate and draw upon one another at a strategic level.

Figure 11-2. Mind map of Insider Threat SIP developed in FreeMind

The SIP phase of the SPM Framework is an attempt to add a level of strategic thinking to an otherwise highly tactical and dynamic set of activities. Your SIP efforts do not need to be incredibly complex or sophisticated to be successful. Much more important is that they be conscious, consistent, and continuous over time in managing the increasing and varied levels of information and data that emerge from your security metrics projects.

Summary

The SIP component of the SPM Framework is meant to guide you from the tactical management of individual security measurement projects to the strategic management of groups of SMPs devoted toward a unified objective or initiative. The SIP approach still places primary importance on the metrics and data collected during the SMP process, but it seeks to contextualize the results of multiple measurement efforts and to extract insights not only from the individual results of these efforts but also from the relationships and interactions among them. These insights can include higher level security knowledge based on correlating data, or they can result in new directions for security measurement goals and activities.

Implementing a SIP requires some forethought and planning if the program is to be successful. Issues of management support and appropriate staff and resource allocation should be considered and resolved prior to starting the effort. Similarly, the SIP requires that you give careful thought to the definitions and objectives of security necessary to define the strategy that the SIP is being used to coordinate.

Primary SIP activities include documentation, information storage and sharing, and collaboration over time. In many ways, the SIP applies principles of knowledge management to the security metrics program, and you can enhance your efforts by engaging existing content and knowledge management teams within your organization to help you set up and drive your improvement program. By establishing appropriate documentation, making that information available to the organization, and encouraging its use and reuse, the SIP can become a powerful tool of organizational learning and capability maturity. A variety of tools, both commercial and open source, can be used to help you manage SIP activities, ranging from traditional communication techniques such as e-mail and instant messaging, to new information sharing tools such as blogs, wikis, and groupware applications that are available to encourage and enable collaboration.

The SIP itself is also subject to measurement and assessment. Security process management and improvement is less about revolutionary leaps and much more about the changing of daily organizational habits and the creation of ongoing action that is regular and stable, keeping security improvement as a constant top-of-mind concern. Metrics can be developed as a part of the SIP that not only track the effectiveness of the program, but also use baseline data from repeated SMPs to establish whether or not your organization’s security is improving over time compared with the definitions and goals that you have established.

Further Reading

Archibald, R. Managing High-Technology Programs and Projects, 3rd Ed. Wiley, 2003.

Rosen, E. The Culture of Collaboration. Red Ape Publishing, 2007.