Case Study 4

Getting Management Buy-in for the Security Metrics Program

Craig Blaha has been a friend and colleague for several years in my university life. The fact that he’s also a security professional allows us to talk about our day jobs in the light of the social science research that we were and are engaged in as academics. Research in the corporate IT security world can mean a very different thing from research in academia, and it is great to have a colleague with whom I can talk (and complain) about things such as the neglect of qualitative methods, validity and reliability in industry research, and the need for a more rigorous approach to measuring security. Craig and I also share another understanding that is central to his case study: the fact that the political environment of universities can make the corporate world look like a hippie commune. In academia, where common goals such as revenue growth or shareholder value are alien concepts, outreach, consensus, and buy-in can be hard to come by. In academic environments you may find that working together can actually be viewed as detrimental to one’s long-term interests and success is considered by many to be a zero-sum game.

Craig’s case study concerns a research project that was designed to measure and improve buy-in in a university IT environment; it’s a lesson from the trenches. We all face competition for resources and status in our IT security activities, and Craig’s point that becoming what I like to term “a security diplomat” is necessary for success is well taken. As any good politician knows, the best way to advance your goals is to understand the goals of others and show them that their goals are your goals.

Craig’s case study is a good closer for the book, because his points are central to Security Process Management (SPM). IT security is rapidly losing its ability to function in a relative vacuum with little visibility or accountability. No matter your organizational psychology or your approaches to solving your security challenges, you will need help from other stakeholders. Craig’s insights into getting buy-in from those stakeholders can help you better understand how to get buy-in from your own.

Case Study 4: Getting Management Buy-in for the Security Metrics Program

by Craig Blaha

Information technology, in both the private sector and higher education, has one thing in common: technology is the easy part. My job at various institutions during the past 15 years has been to convince stakeholders that the chosen direction, whether it be the implementation of a new software package, major changes to existing software, or process change, is the right one. Not only have I had to convince people that we were moving in the right direction for the organization, but I had to prove that this move was in the best interest of both their particular unit and their individual career. I’ve worked in both corporate America and higher education, with the bulk of my years spent in higher education. I’ve had a range of responsibilities, from standing up an information security organization where none had existed before, to implementing an incident response team, to developing an IT policy division.

I have also been in the position of acting as the point person on some major projects, where I spent the majority of my time providing evidence, building relationships, and giving presentations to convince people that the IT unit knew what it was doing. I am currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Federal Information Policy, focusing on information security, privacy, and the preservation of records. This diverse background puts me in a unique position to discuss not only the implementation of a metrics program, but how to make that program “stick” over time.

Through all of this experience, I have found that one of the most difficult aspects of working in the field of IT is getting people to agree that the work you are doing is worthwhile, to trust you and your team, and to communicate effectively the things you think are important for them to know related to security and technology. To illustrate my insights, this case study will describe an experience in which I was part of a team of researchers that set out to determine what IT metrics matter to different groups of stakeholders. The answers we found may surprise you, but first I want to offer an example of a security leader successfully navigating these human, political, and social waters.

The CISO Hacked My Computer

I heard the following anecdote while attending a SANS leadership course. Will Peregrin, the director of New York’s Office of Cyber Security and Critical Infrastructure Coordination, worked with the SANS Institute and AT&T to develop a phishing awareness program. This program had two alternating parts: an awareness program and what they referred to as “inoculation.” The initial awareness phase consisted of a phishing awareness raising e-mail that was sent to 10,000 employees. About a month after that initial e-mail, the inoculation phase began. A phishing e-mail was sent to those same employees, asking each for his or her username and password. Seventeen percent of the targeted employees typed in their username and password, which triggered a message that let them know they had failed the test.

Failing the test meant that you were required to sit through a training video and answer some questions about phishing. After this second training session, the phishing test was tried again. This time, only 8 percent of those tested responded with their username and password.

It is easy to see how 17 percent and 8 percent are useful metrics. These numbers help to tell the story of a security awareness program that is working, at least to an extent. Getting the last 8 percent of employees to avoid giving away their username and password may be a case of diminishing returns, but the metrics help tell the story. Now imagine if Peregrin tried this inoculation without first making sure his colleagues at the senior management level were not only aware of the program, but had given explicit permission to use their personnel time in this way, or if SANS and AT&T had independently conducted the inoculation test without Peregrin’s awareness. Regardless of the numbers generated by such a test, the business leaders of that organization would be up in arms! Getting buy-in from senior management and important stakeholders is critical not only for career longevity, but for the long-term success of your SIP.

What Is Buy-in?

Buy-in is not approval. A manager or colleague can approve an action without having any “skin in the game.” In fact, in some highly political situations, you will find leaders who will approve of a tactic or program, even though they completely expect it to fail. Sometimes the failure of a program will help them achieve some other long-term strategic goal, often at the expense of the current security team.

Buy-in is more than just approval, it is both agreement that you are doing the right thing and an investment in the success of that action or strategy. Buy-in is most likely to be achieved when other leaders in your organization trust you to use institutional or corporate resources in a responsible manner that supports the goals and mission of the organization.

Buy-in matters for a number of important reasons. Even during positive economic times, financial resources within an organization are limited. These resources inevitably are divided up among competing priorities. As financial times become more challenging, as they are now, this competition heats up even more. If you happen to be a leader who has demonstrated appropriate use of organizational resources in the past, the chances of your securing those resources in a competitive environment are greater. If you can convince a critical mass of your colleagues to support your initiative, you are effectively gaining their buy-in when they publically support your project, especially if by supporting you they are reducing the funds available for their own projects and initiatives. This sets up a feedback loop in which successful competitors for resources have a leg up the next time a competition comes around, allowing them an opportunity to garner more resources. This cycle lasts only if you have the continued support of your colleagues and senior management.

Getting buy-in prior to making changes that require significant financial or political support from your organization makes continued support possible. Part of maintaining buy-in and support is letting your stakeholders know when there is a problem. This allows them to be “in the know,” rather than learning of the problem in a surprise hallway conversation with the CIO that puts them in an awkward political position. By making key people aware of a problem as soon as you become aware of it, they have an opportunity to advocate on your behalf in those hallway conversations.

Building these relationships over time, developing trust, and aligning your goals in support of both the mission of the institution and the goals of other senior leaders and key players helps you make the case to continue your program during tough economic times. If key decision-makers aren’t convinced of the value your program is bringing to the organization because you haven’t developed these relationships, you may be doing your organization a disservice. When the senior leadership of your organization is faced with tough economic choices, they won’t be well informed enough about the security needs of the organization to make decisions that are grounded in a foundation of fact.

Corporations vs. Higher Ed: Who’s Crazier?

Higher education is the “big leagues” of organizational politics. The wide variety of funding, missions, politics, and regulations leads to a plethora of different stakeholders that you need to consider when undertaking a measurement project in the university environment. Any one of these stakeholders can bring your project to a halt, even if your project has little to do with their operation. The political reality of this environment forces you either to complete projects before anyone notices the project is underway or manage the risks by getting buy-in up front.

Corporations have a significant advantage over higher education: a shared goal. Each employee of a corporation can point back to profit as a significant driving factor. Higher education can’t even conduct an ROI calculation! The investment can be measured, but what would the return be? Enrolling more students? Improving the ranking of the school? Hiring more hotshot professors? These goals can be at odds with one another, and there is no accepted quantitative way to measure return. The culture supports individual contributions and contributors, granting individuals the opportunity to command significant resources, even if by doing so they damage the overall health of the organization.

This hyper-politicization of higher education is what makes this case study so valuable. You may not need to address all the findings from this study in your project or program, but your chances of being blindsided by a political football are reduced by being aware of them.

Higher Education Case Study

We have talked about what buy-in is and why it is important, and how we can use the supercharged political environment of higher education to bring some lessons back to the real world. With that said, determining what to measure, how to measure it, and to whom to report the results can be more of an art than a science. All of the factors discussed so far were derived from a research/business study conducted at four major research universities during the course of a year. This study was both an academic study meant to look at the organizational, social, and political issues related to security and IT, and a business study geared toward the ongoing measurement of management buy-in for the implementation of an IT metrics program.

The original study was designed to accomplish three different goals. The first goal was to account for all IT spending at each university and to look for trends and opportunities for cost savings. The second was to identify key metrics related to the IT services provided by the central IT organizations at each university. The third was to identify key services the central IT unit provided.

The interviews began with a broad focus on quantitatively measuring the IT services, but the scope of the project changed considerably as we progressed through the interviews with the different stakeholders. It became clear that buy-in couldn’t be measured quantitatively. Interviewing individual stakeholders about their concerns, sometimes in an unstructured interview format, produced some very clear narrative themes that helped us figure out what steps needed to be taken to make our continuing metrics program successful.

Project Overview

The original project had some ambitious goals: to account for all IT spending at each university, to develop service catalogs related to the services provided by the central IT departments at each university, and to identify key metrics that would represent the services covered in the service catalog in a way that was meaningful both to the service provider and the customer. One of the overarching questions of this research was how to use metrics to communicate the importance of IT and security to the various stakeholders of the university. While the overall scope of the project was general IT, my own background and experience made me particularly interested in how the findings of the study could be specifically tied back to buy-in for security metrics programs. The metrics we hoped to develop based on the research were measurements of IT effectiveness from the customer perspective, a goal that is easily applied both to security and non-security–related aspects of IT.

The approach of the research team was to interview key stakeholders outside of the central IT administration. The following questions were asked of each interviewee:

![]() From your perspective, what are the goals, strategies, or objectives you are striving to achieve to make the university a better learning and working environment (what matters)?

From your perspective, what are the goals, strategies, or objectives you are striving to achieve to make the university a better learning and working environment (what matters)?

![]() What measurements are you using to gauge the progress toward achieving these goals (how do you know you are succeeding)?

What measurements are you using to gauge the progress toward achieving these goals (how do you know you are succeeding)?

![]() From your perspective, how does IT help you make your work successful (role of IT)?

From your perspective, how does IT help you make your work successful (role of IT)?

![]() What do you think IT should measure and why?

What do you think IT should measure and why?

Themes

We noticed three themes in the responses from our subjects:

![]() Operational goals (what we are trying to do)

Operational goals (what we are trying to do)

![]() Barriers to those goals (what is keeping us from doing it)

Barriers to those goals (what is keeping us from doing it)

![]() The role of IT in supporting those goals (what we think you can do to help)

The role of IT in supporting those goals (what we think you can do to help)

Not surprisingly, each interview the team conducted resulted in the identification of the operational goals of the interview subject and his or her department. In addition, respondents were quick to identify the barriers that they believed were inhibiting their ability to achieve these goals. Lastly, the respondents were usually pretty clear on what role they believed IT could play to remove barriers or help them achieve their goals. Importantly for our purposes, the idea of data security was surrounded by fear and confusion.

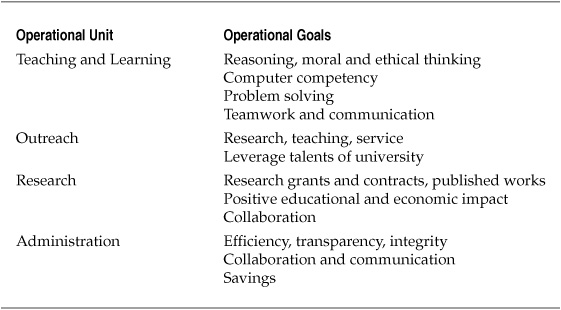

Operational Goals

The operational goals of each area varied widely, as shown in Table 1. In the teaching and learning group, goals predictably surrounded the development of professionals and leaders as part of the educational experience. There was an emphasis on developing the skills of reasoning and moral and ethical thinking in students, as well as computer competency broadly defined. In addition to these foundational skills, leaders from the teaching and learning areas emphasized the development of problem-solving skills, teamwork, and communication as important to the long-term success of the students.

The representatives of the outreach function identified two broad goals: support the combined university goals of research, teaching, and service, and leverage the talents in the university to help industry partners with research and development and to raise the profile, and hopefully increase the endowment, of the university.

The outreach group wanted to continue the educational community and culture created at the university. This seems contrary to what we usually hear about alumni and development just trying to squeeze as much money out of the alumni as possible, but I have worked closely with leaders in a variety of alumni and development departments in the past, and the most dedicated ones say fundraising is a side-effect of doing their job well. A university tends to develop a certain worldview in its students, often as a consequence of the academic culture created by the faculty and the social culture created by the students. If that experience is valuable to a student, she tends to want to offer support to ensure the part of the culture she enjoyed or found valuable will continue. Whether it was studying abroad, using the computer lab, or learning from a favorite professor in economics, donating money allows former students to be part of a continuing conversation about how the world should be. The best alumni and development officers engage alumnus in that conversation.

Table 1. Operational Goals

The research group identified three major goals: The first was to increase the volume and quality of research grants and contracts, and published work. Second, the research group wanted to contribute to the university’s ability to create a positive educational and economic impact. Lastly, increasing collaboration was one of the most difficult goals the research group had set for itself. With hundreds or thousands of researchers all working on their own particular set of interests and problems, some jealously guarding their discoveries, increasing collaboration was a difficult social and technical problem.

The various individuals representing the administration group communicated goals that were distinctly different and more operationally focused than the other groups. Efficiency, transparency, and integrity were at the top of the list. The goals of collaboration and communication were also mentioned, as were cost effectiveness and reduction.

Regardless of the industry, it is important that you understand the goals of the operational units you are trying to protect through your SIP. To convince these units to comply with your efforts and to educate them to understand the overall program you are trying to implement, you will need to speak their language and understand what exactly they are trying to accomplish.

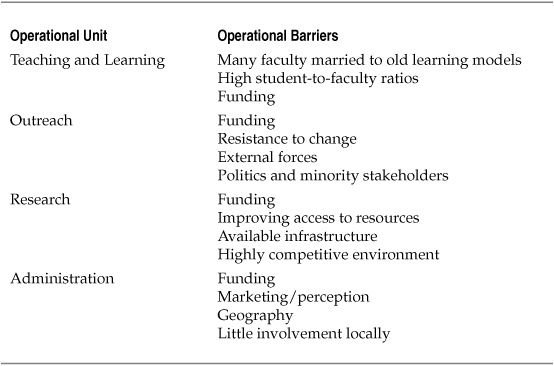

Barriers

Each group also mentioned barriers that kept them from achieving the goals they had set, limited their success, or frustrated their efforts in some way, as shown in Table 2. The most common barrier mentioned by everyone was funding— a situation that will also be familiar to anyone chasing resources in the for-profit world.

Table 2. Operational Barriers

Funding is a barrier in just about any organization, but major research universities often have a more complex challenge. Some of this complexity comes from the multiple funding sources that institutions of higher education depend on. Some people assume that tuition is the primary source of funding, but a variety of different sources actually make it possible for a university to keep its doors open and its lights on. State funding is one source, particularly for public education institutions, but this source has been dwindling to the extent that higher education leaders no longer refer to their institutions as state-sponsored but state-molested! For many institutions, state funding has decreased, but the state’s rules, requirements, and mandates have not.

In addition to the complexity of funding, universities have to deal with state and federal regulations, just as any corporation must. Most states have sunshine laws or open records acts that allow citizens to request certain records from public institutions. A variety of statutes are related to data breaches, and some states require reporting of data breaches based on the state of the data subject—in other words, if a university in Montana hosts data about a student from California and experiences a data breach, the Montana university has to report the breach, at least to that one California resident. Finally, universities manage everything from student records to health records to financial records, and are covered by an alphabet soup of statutes: the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Gramm-Leech-Bliley (GLB), and Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX).

For the teaching and learning group, one significant cultural barrier was the perception that many faculty are married to old learning models. Persuading tenured faculty members to make a change to teaching styles they have developed during the past 20 or more years was a significant barrier. Another barrier was the fact that an individualized, flexible learning model is difficult to achieve with one teacher and many students—sometimes up to 1000 students in one class.

For the administration group, resistance to change was also an important barrier— not only technological change and the operational and business process adjustments that such change requires, but organizational change such as reducing administrative overhead and collaboration across administrative groups. External forces were also cited as a critical barrier to success in the administrative group. Financial challenge is the most salient recent example, but over the course of the last ten years, the move to outsource or automate more administrative tasks has also been a challenge. I briefly discussed the complexity of politics in higher education, and the amount of overhead that this complexity adds to any significant change effort was held out by the administrative group as one of the major barriers to success. In addition to the political issues discussed earlier, respondents focused on minority stakeholders—those individuals who have a strong influence on the outcome of an effort without having a strong vested interest in the ongoing results.

The respondents from the research group put funding for research at the top of the list. Acquiring adequate funding to support research is a continuous competitive process, and the grants that are secured to provide financial support require a significant effort to manage once they have been acquired. Corollary to research funding is access to resources. This category covers a wide range of details, including office space and supplies, qualified and committed research and administrative assistants, and technological resources such as infrastructure, network, and security support.

Research grants account for a significant source of funds at research universities. At most top-level research universities, the institution takes 50 percent of the grant funds brought in by researchers or research teams, right off the top. This means a $1 million grant brings $500,000 to the institution and $500,000 to the researchers, and some of this is used to pay someone else to teach the courses the faculty are required to teach so they can spend time doing the research for the grant.

Related to research is the commercialization of intellectual property. Researchers can earn income from their discoveries in a variety of ways, but many of them include not only the granting agency, but also the institution and often the commercial entity that will make products based on the discovery.

Outreach respondents identified a set of barriers that were qualitatively different from those of the other groups. At the top of the outreach list of barriers was the funding issue that had been highlighted by others, but marketing and the perception of the university were a close second. The combination of these two elements played a major role in the success or failure of the outreach representative’s efforts. Geography was also cited as a barrier; making connections with alumni or potential partners is easier when you are in close geographic proximity, but it is much more difficult if the university is located in rural Pennsylvania, for example.

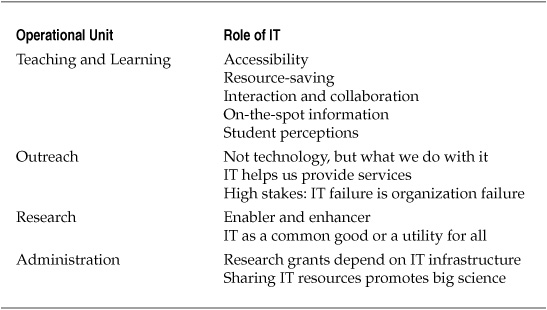

The Role of IT

The role of IT in supporting the goals and daily operations of these groups is the last theme and is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. The Role of IT

The teaching and learning group put accessibility at the top of their list, which is reasonable since accessibility is mandated by Section 508 regulations, which require institutions to make learning and administrative material available in an accessible manner or to provide an accessible alternative to those materials. IT often provides a solution to this problem. Technology plays a more and more significant role in teaching and learning, although the role technology plays can be overstated. For example, when I worked as the webmaster at The College of New Jersey, we experienced a prolonged power outage that sent home all administrative staff with a recommendation that faculty leave as well. It was a beautiful spring afternoon, and as I walked past the philosophy building I noticed a professor had convened his class on the lawn. This emphasized for me the support role IT plays in the classroom: it is important, but often it is by no means essential.

Resource saving, interaction, and collaboration are all roles that IT can play, according to the teaching and learning group. With incredibly large classrooms and few instructors, technology makes it possible to make the student-to-teacher ratio seem lower than it actually is. This can be achieved through recorded podcasts of a lecture, online discussions of the readings or homework assignments, and other methods. Instructors, administrators, and students all expect on-the-spot information. Instructors expect to be able to determine who has actually attended their large lecture sections or how many students are eligible to take the next test. Administrators want to be able to forecast classroom utilization, and students want up-to-the-minute information about availability of their favorite class.

IT was also seen as either an opportunity or a liability when it comes to student perceptions. Educause, a higher education IT practitioners’ group, even publishes a pamphlet to grade higher education institutions based on the technology the institution provides to students. More than ever, students see themselves as consumers of higher education, looking critically at each institution and shopping for the best deal.

For respondents in the administration group, the consistent message about the role of IT was it is not the technology, it’s what we do with it that matters. IT was seen as essential to the administrative group’s ability to provide services. The success of the administrative organization was tied closely to the success of the IT department, and vice versa.

The outreach group characterized the role of IT as an enabler and enhancer to their ability to achieve their mission and goals. IT was seen as fundamental to some core initiatives as well as supporting the overall functionality of the group. IT was described as a utility and the sentiment was expressed that much of it should be considered a common good, and priced accordingly.

The research division respondents depended heavily on technology infrastructure and emphasized that sharing IT resources from around the world promotes big science.

Findings

The research team noticed some very interesting threads when we compared notes from our various interviews. One of our most important takeaways was the fact that people had not had a conversation like this with a representative from the central IT unit—ever! Another very interesting trend that was consistent throughout almost every interview was the clear sentiment that metrics don’t matter! Without prompting, a large number of respondents stated that they were particularly not interested in metrics or a metrics program. The most important takeaways were these:

![]() Communication

Communication

![]() Metrics don’t matter

Metrics don’t matter

![]() Alignment

Alignment

Communication: Two Ears, One Mouth; Do the Math

The communication theme included some of the most common refrains we have heard time and again when it comes to communication. The fact that these same familiar warnings have come up again means I should share them one more time.

“No news is good news” was the most common refrain, indicating that customers and stakeholders believed that if they didn’t hear anything from the IT group, things must be as they should be. The flipside is that when they did hear from IT, they expected bad news. This preconception of bad news bred mistrust, since the first exchange in any communication was the customer trying to figure out what exactly the IT person was saying is broken. At the same time, this sentiment was backed up by the request for better communication from the IT group, in both good times and bad. A communication plan that focuses both on communicating positive change before it happens and a consistent approach to communication when things do go wrong will go a long way.

One of the most common questions we heard was “What’s going on?” It is common for an IT organization to spend the time to troubleshoot a problem, with technicians believing that their time is far better spent figuring out and fixing whatever is wrong than communicating to the community when they really don’t have any information to share. The customer does not support this sentiment, however.

Consistently, respondents requested to be informed of the state of affairs, especially during an outage, even if there is no change in status. And these communications better be in plain English, not techno-babble. Consistently throughout our interviews we were warned that IT people had no idea how to communicate with normal humans; our use of tla’s (three letter acronyms) and dependence on deep technical details to explain an issue made us impossible to communicate with.

We also heard that IT had a real marketing problem. We lacked the ability to listen to the customer and try to understand what the real issue was, or what the customer was trying to request. Our customers didn’t believe we understood their real mission, that we didn’t really know what they were trying to accomplish and how, through our expertise in IT, we could help. To establish trust and build a relationship, our respondents recommended that we work harder at establishing relationships with our constituents, focusing on working toward shared goals, metrics, and alignment.

To this end, some of the recommendations that appeared consistently in our conversations were that we ask some essential questions. What is the value derived from IT by the customer? What are the IT-driven results that matter to the customer? This question allows for measuring performance against desired outcomes, but it requires IT staff to convert customer expectations to service standards. How are these results measured? There are many different types of performance measures: reliability measures, responsiveness measures, project measures, utilization and adoption rate measures, and client satisfaction measures.

Many Metrics Don’t Matter

When these groups were asked about metrics, their responses indicated that they were not in the least bit interested in metrics, because too often the metrics become the goal. Only metrics that support a goal should be considered. Two statements really stood out among the others: it doesn’t matter unless you measure it; and if it doesn’t matter, don’t measure it!

The respondents that we spoke to all agreed that behavior beats metrics; if the security staff or IT staff have taken the time to build a relationship and understand the mission and challenges of the operational unit, the words and deeds of the security folks will be judged based on these prior efforts. Overall, operational leadership is tired of metrics that don’t matter. These are measurements that are held up as examples of success, which are meaningless to the operational units. “Defensive metrics” is a term we encountered as well. This term was used to indicate CYA (cover your ass) metrics that may not mean anything significant to the people trying to support the mission of the operational unit, but that make it difficult to discuss areas for improvement in the IT or security staff. Much of this was perceived as fear of accountability—metrics that are created for the sake of protection, not for the cold, hard, objective feedback that such measurement could offer.

Align the Business with the Needs of Security

The third finding, collaborative metrics, highlighted the customer sentiment that leadership from the IT department was required for such a thing as collaborative metrics to be possible. It was up to the IT leadership to start the conversation about metrics with the various departments they served.

The process proposed by the individuals we interviewed maps exactly to the assertions in the SIP model. The first step, according to the customer, is for the IT department to present a metric. This metric should be based on repeated conversations with the customer that have led the IT or security department to understand the mission and goals of the customer—conversations that should build trust. The IT department should discuss the proposed metric(s) regularly, especially if the measurements indicate progress or problems. The customer and the security or IT department should together determine whether the metric ends up being useful, and this process should be repeated on an ongoing basis, since both business requirements and the capabilities of the IT service provider will change.

The process of finding alignment between the security staff and the operational unit is a continual one. One of the first and most important steps is to identify the stakeholders that will be affected by your Security Improvement Program. These individuals or groups are not necessarily the people that will consume the metrics that you create—but I’ll talk more about stakeholders a bit later, when I discuss tools that can influence the direction of other operational units.

After stakeholders are identified, you must engage them during key parts of the planning process. One of the common complaints we heard was about planning that leaves out the middle. Although you may engage the leadership of an important stakeholder group, for particularly important projects you should keep in mind that communication is a difficult task in any organization. If having your message heard at all levels of the organization is important to the success of the project, you may need to make the extra effort to determine on your own whether the message is getting out, and then take steps to improve communication within other groups, at least for the short term or during critical periods of your project.

A great way to get to know the culture, values, and communication style of an organization is to ask people what metrics and measures they already have in place that are valuable, and ask which of these they find less valuable or redundant. This will give you a sense of how the organizations measure themselves and how they map either the services they provide or the services they consume from other providers to measurements, to determine the success, failure, or general status of the services in question. In addition, this will give you a sense of how much work you will need to do to integrate the metrics that your security improvement plan creates into the planning and processes of the operational unit.

Key Points

Key points we took from the series of interviews performed at the four major research universities included first and foremost, focus on the mission. Not our mission—theirs! The operational units that you are working with and trying to convince to change or to get on board with your Security Improvement Program are all working hard to accomplish some very specific goals. In a well-managed department, everyone in that operational unit is aware of that goal or set of goals and is working hard to limit anything that will keep them from achieving those goals.

One of the more difficult things to keep in mind and to adjust to is the fact that these goals may be different for each unit, depending on the size of the organization. In a large organization, the Security Improvement Program will span multiple units, some of which may not have heard of each other or worked together in the past. Understanding customer needs in any environment is important, but in a complex environment with multiple, conflicting priorities, understanding the varied needs of the customer is sometimes the only way to resolve conflict or negotiate buy-in.

We also learned that metrics need to be collaborative. Working with the customer to determine what they find valuable and how they are perceiving your efforts and the metrics that you are sharing with them, and then adjusting to that feedback, are important for the long-term success of your Security Improvement Program. An important point to underscore here is that active listening is communication. As technologists, we can sometimes forget to listen and switch quickly into problem-solving mode, sometimes before the problem has even been thoroughly defined.

Lastly, strategic and operational planning done in conjunction with an operational department can have a fatal flaw: the quality of communication within the operational unit. Depending on the importance of the particular piece of your Security Improvement Program in which you are engaged, you may want to “supplement” communication on the other side of the fence to make sure that the right messages are getting to the right people.

Influence and Organizational Change

Inherent in this discussion is the need to persuade others of the importance, relevance, and value of the SIP you are undertaking. Our study showed how a variety of stakeholders wanted to be communicated with, but the underlying assumption is that you and your stakeholders have a shared goal. We know this is not always the case, especially with security. Business schools refer to this type of influence as a non-market strategy because it does not focus on supply and demand, as a market strategy would, but on four factors:

![]() Issues

Issues

![]() Stakeholders

Stakeholders

![]() Power

Power

![]() Information

Information

The combination of these four factors offers important tools that will improve your ability to influence individuals and groups.

Issues

Issues are basic topics of interest or areas of concern that are important to the business. Issues include policy, technology, and events and activism. Policy issues include regulations imposed by agencies that cover the industry in question including federal, state, or local agencies. Issues include industry standards such as those imposed or recommended by NIST, IEEE, and other industry-level professional organizations. Federal and state laws are also considered part of the policy arena, since laws often drive policy at the organizational level. Many of these factors end up being implemented, especially at large organizations, as regulations, standards, and processes that are imposed internally. Smaller organizations tend to have a reduced policy overhead, but they are still held to the same standards and laws—they just aren’t always mirrored within the organization as local policy or process. Change or a new proposed policy at any one of these levels can be considered an issue if it changes the non-market environment of the business.

Technology changes can also be considered issues. New technologies that stand to revolutionize the business usually require significant adjustment and can sometimes even lead to business failure. Changes in existing technologies that aren’t necessarily revolutionary can increase or decrease competitive advantage—either your advantage or that of your competitor—leading to a new set of opportunities and challenges that the business had not faced in the past.

Events and activism are a separate category, because they are both difficult to predict and control. These can include societal events such as the September 11 bombings or the fallout from the discussion of global warming. The category of events also includes natural events such as natural disasters and their societal and social impacts. The devastating earthquakes in Haiti are a clear example of the level of influence a natural disaster can have on public discourse. A significant natural disaster almost always has an economic impact (as well as many societal ones). Water, fuel, and other resources can be cut off when a natural disaster occurs in the supply country.

Political events can have a similar effect on the supply of raw or finished materials essential to the business in question. Regime changes or coups are clear examples that have been historically significant, but subtler and sometimes more difficult to deal with (from a business relationship perspective) are political shifts within stable governments. New politicians or parties have their own set of preferred vendors or suppliers that a business will have to learn to maneuver around and deal with.

Stakeholders

Clearly determining the issue that you are trying to address is a critical first step in being able to persuade an individual or group to follow the path you have outlined. The next step is determining the stakeholders. The term “stakeholder” used to mean literally the holder of the stake—the third party who holds the money in a bet. It has come to mean something different in business and project management and these days refers to a person or group that has an interest in the outcome of a project or process. As mentioned, accurate determination of stakeholders is important, since these are the people you will be attempting to influence regarding the issue.

Power

Influence is also dependent on power and is most clearly seen in the fierce competition for scarce resources. In this setting, power comes from two sources: positional and personal.

Positional power comes from a person’s title and position in the organization chart. It is this type of power that can compel compliance, if not enthusiastic participation. The president, provost, deans, and vice presidents all have the ability to snap their fingers and get things done, just by the weight of their title.

Ignoring the org chart, we find another source of power that is relative to the individual. We can call this “personal power,” and it comes from both recognition of accomplishments and building relationships over time. Personal power that originates from recognition often occurs because some people are considered excellent, or at least well recognized, in their field.

Another source of this type of power is the ability to bring in high-dollar amounts of funding. Relationships are another source of personal power. Some individuals have been around for a long time and “know where the bodies are buried.” These people maintain the institutional knowledge and culture of the organization, and their opinions are respected and often sought out, regardless of their position in the org chart. Others have taken the time and made the effort to build relationships with other groups around campus, and their opinions and decisions are respected because of the trust and political capital they have built up over time.

This doesn’t mean that every step of every project or initiative needs to include all of the people in your stakeholder list, but it is a career-enhancing move to think through the list as you undertake a significant initiative and see if you should communicate with one of these groups.

Information

Information, in this context, refers to what the stakeholders know or believe about the factors affecting the issue. If we consider security, for example, news coverage of a particular event can raise fear, whether rational or irrational. As the chief security officer, you may have received a phone call or a question one Monday morning such as “How does the Chinese Google hack effect us?” and this may not have been such an irrational question. I worked at one institution where the head of finance for our department would regularly show up to meetings with one question: How come computers cost so much? She would bring in a newspaper clipping with an ad for a $349 special on home computers, asking why we weren’t purchasing these and saving significant amounts of money. Explaining why may—not always, but it can—limit the amount of time you spend on this type of question. Other times it is more effective simply to explain it to the other people at the table, with the hope that they don’t maintain the same expectation.

Conclusion

This empirical study has direct relevance for the implementation of security programs in corporations. Politics, power, and influence are significant factors in any environment, but in higher education, these issues are brought to the fore. The lack of a shared goal such as profit, the provision of service, or the production of a product makes higher education a highly charged political environment and the perfect place to study the influence these factors have on the implementation and maintenance of a metrics program.

You don’t have to have buy-in before the Security Improvement Program is implemented. In fact, it is advisable to start with the small but important aspects of security over which you have complete control. This will allow your team to demonstrate success in ways that are not threatening to other departments and their budgets, so that you can create a solid foundation on which to build.