Chapter 16

Writing Java Applets

In This Chapter

![]() Creating a simple applet

Creating a simple applet

![]() Building applet animation

Building applet animation

![]() Putting buttons (and other such things) on an applet

Putting buttons (and other such things) on an applet

With Java’s first big burst onto the scene in 1995, the thing that made the language so popular was the notion of an applet. An applet is a Java program that sits inside a web browser window. The applet has its own rectangular area on a web page. The applet can display a drawing, show an image, make a figure move, respond to information from the user, and do all kinds of interesting things. When you put a real, live computer program on a web page, you open up a world of possibilities.

Applets 101

Listings 16-1 and 16-2 show you a very simple Java applet. The applet displays the words Java For Dummies inside a rectangular box. (See Figure 16-1.)

Listing 16-1: An Applet

import javax.swing.JApplet;

public class SimpleApplet extends JApplet {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

public void init() {

setContentPane(new DummiesPanel());

}

}

Listing 16-2: Some Helper Code for the Applet

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import java.awt.Font;

import java.awt.Graphics;

class DummiesPanel extends JPanel {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

public void paint(Graphics myGraphics) {

myGraphics.drawRect(50, 60, 220, 75);

myGraphics.setFont

(new Font("Dialog", Font.BOLD, 24));

myGraphics.drawString("Java For Dummies", 55, 100);

}

}

Figure 16-1: Nice title!

When you run the code in Listings 16-1 and 16-2, you don’t execute a main method. Instead, you run a web browser, and the web browser visits an HTML file. The HTML file includes a reference to the applet’s Java code, and the applet appears on your web page. Listing 16-3 shows a bare minimum HTML file.

Listing 16-3: A One-Line Web Page

<applet code=SimpleApplet width=350 height=200></applet>

These days, most web browsers make it difficult to run Java applets. So in Figure 16-1, I don't run Firefox, Internet Explorer, or any other commonly used web browser. Instead, I run Java's own Applet Viewer — a small browser-like application made specifically for testing Java applets.

appletviewer name-of-the-file-containing-Listing-16-3

Waiting to be called

When you look at the code in Listings 16-1 and 16-2, you may notice one thing — an applet doesn’t have a main method. That’s because an applet isn’t a complete program. An applet is a class that contains methods, and your web browser calls those methods (directly or indirectly). Do you see the init method in Listing 16-1? The browser calls this init method. Then the init method’s call to setContentPane drags in the code from Listing 16-2.

Now, take a look at the paint method in Listing 16-2. The browser calls this paint method automatically, and the paint method tells the browser how to draw your applet on the screen.

A public class

Notice that the SimpleApplet in Listing 16-1 is a public class. If you create an applet and you don’t make the class public, you get an Applet not inited or a Loading Java Applet Failed error. To state things very plainly, any class that extends JApplet must be public. If the class isn’t public, your web browser can’t call the class’s methods.

The Java API (again)

The code in Listing 16-2 uses a few interesting Java API tricks. Here are some tricks that don’t appear in any earlier chapters:

drawRect: Draws an unfilled rectangle.Look at the call to

drawRectin Listing 16-2. According to that call, the rectangle’s upper-left corner is 50 pixels across and 60 pixels down from the upper-left corner of the panel. The rectangle’s lower-right corner is 220 pixels across and 75 pixels down from the upper-left corner of the panel.I wanted the rectangle to surround the words Java For Dummies. To come up with numbers for the

drawRectcall, I used trial and error. However, you can make the program figure out how many pixels the words Java For Dummies take up. To do this, you need theFontMetricsclass. (For information onFontMetrics, see the Java API documentation.)- The

Fontclass: Describes the features of a character font.Listing 16-2 creates a bold, 24-point font with the Dialog typeface style. Other typeface styles include DialogInput, Monospaced, Serif, and SansSerif.

drawString: Draws a string of characters.Listing 16-2 draws the string

"Java For Dummies"on the face of the panel. The string’s lower-left corner is 55 pixels across and 100 pixels down from the upper-left corner of the panel.

Making Things Move

This section’s applet is cool because it’s animated — you can see an odometer change on the screen. When you look at the code for this applet, you may think the code is quite complicated. Well, in a way, it is. A lot is going on when you use Java to create animation. On the other hand, the code for this applet is mostly boilerplate. To create your own animation, you can borrow most of this section’s code. To see what I’m talking about, look at Listings 16-4 and 16-5.

Listing 16-4: An Odometer Applet

import javax.swing.JApplet;

import javax.swing.Timer;

import java.awt.Color;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

public class Odometer extends JApplet

implements ActionListener {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

Timer timer;

public void init() {

OdometerPanel panel = new OdometerPanel();

panel.setBackground(Color.white);

setContentPane(panel);

}

public void start() {

if (timer == null) {

timer = new Timer(100, this);

timer.start();

} else {

timer.restart();

}

}

public void stop() {

if (timer != null) {

timer.stop();

timer = null;

}

}

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

repaint();

}

}

Listing 16-5: The Odometer Panel

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import java.awt.Font;

import java.awt.Graphics;

class OdometerPanel extends JPanel {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

long hitCount = 239472938472L;

public void paint(Graphics myGraphics) {

myGraphics.setFont

(new Font("Monospaced", Font.PLAIN, 24));

myGraphics.drawString

("You are visitor number " +

Long.toString(hitCount++), 50, 50);

}

}

A complete web page to display the applet in Listings 16-4 and 16-5 might consist of only one line, such as

<applet code=Odometer width=600 height=200></applet>

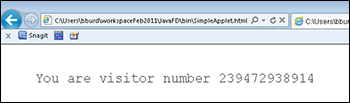

For a snapshot of the odometer applet in action, see Figure 16-2. Notice the number in the figure. It’s not the same as the starting value of the hitCount variable. That’s because every 100 milliseconds the applet adds 1 to the value of hitCount and displays the new value. The odometer isn’t reporting an honest hit count, but it’s still really cute.

Figure 16-2: A popular website.

The methods in an applet

Most of the method names in Listings 16-4 and 16-5 are standard for an applet. The Java API JApplet and JPanel classes have default declarations for these methods, so you don’t really have to declare these methods yourself. The only methods that you have to put in your code are the methods that you want to customize.

Here’s a list of JApplet and JPanel methods that your web browser automatically calls:

init: The browser callsinitwhen you first visit the page containing the applet. Imagine that you close the web browser. Later, you start the browser running again and revisit the page containing the applet. Then the browser calls the applet’sinitmethod again.start: The browser callsstartright after it callsinit. If your applet performs any continuous work, you can begin that work’s code in the applet’sstartmethod. For instance, if your applet has any animation, the code to begin running that animation is in yourstartmethod.paint: The browser calls thepaintmethod in Listing 16-5 right after it callsstart. (Yes, thestartmethod and thepaintmethod are in different classes, but the browser figures things out because of the call tosetContentPanein Listing 16-4.) Thepaintmethod has instructions for drawing your applet on the screen. For an explanation, see Chapter 14.The browser can call

paintseveral times. For instance, imagine that you cover part of the browser with another window. Or maybe you shrink the browser so that only part of the applet is showing. Later, when you uncover the applet or enlarge the browser window again, the browser calls the panel’spaintmethod.stop: When the applet’s work should cease, the browser calls thestopmethod. Say, for instance, that you click a link that takes you away from the page with the applet on it. Then the browser calls the applet’sstopmethod. Later, when you revisit the page with the applet on it, the browser calls the applet’sstartmethod again.

What to put into all these methods

The code in Listings 16-4 and 16-5 uses a standard formula for creating animation inside an applet. Here’s a very brief explanation:

- The applet implements the

ActionListenerinterface. - The

startmethod creates a new timer with the following code:new Timer(100, this)

Every 100 milliseconds (every tenth of a second), the timer in Listing 16-4 rings its alarm.

When it “rings its alarm,” the timer actually gets Java to call an

action Performedmethod. And whoseactionPerformedmethod does Java call? Once again, the keywordthisanswers the question. In Listing 16-4, the wordthisrefers to this very same code — this instance of theOdometerobject that contains thenew Timer(100, this)call. So every tenth of a second, when the timer rings its alarm, Java calls theactionPerformedmethod in Listing 16-4. How nice and tidy it is! - The

actionPerformedmethod calls therepaintmethod. Under the hood, a call torepaintalways calls somebody’spaintmethod. In this example, that somebody is the code in Listing 16-5. Thispaintmethod draws the wordsYou are visitor number whateveron the screen. - At some point, the day is done, and your browser calls the

stopmethod. When this happens, thestopmethod tosses the timer into the dumpster.

If it weren’t such standard code, I’d feel guilty for explaining this stuff so briefly. But, really, to achieve motion in your own applet, just copy Listings 16-4 and 16-5. Then replace the listing’s init and paint methods with your own code.

So, what do you put in your init and paint methods?

- If you declare an

initmethod, the method should contain setup code for the applet — stuff that happens once, the first time the applet is loaded.In Listing 16-4, the setup code fiddles with a panel:

- It creates a panel by calling the

OdometerPanelconstructor. - It makes the panel’s background white. (This ensures that the rectangle housing the applet blends nicely with the rest of the web page.)

- It forges a rock-solid connection between the panel and the applet. It does this by calling the

setContentPanemethod.

- It creates a panel by calling the

- The

paintmethod describes a single snapshot of the applet’s motion.In Listing 16-5, the

paintmethod sets the graphics buffer’s font, writes thehitCountvalue on the screen, and then adds 1 to thehitCount. (Who needs real visitors when you can increment your ownhitCountvariable?)The value of the

hitCountvariable starts high and becomes even higher. To store such big numbers, I givehitCountthe typelong. I use theLongclass’stoStringmethod to turnhitCountinto a string of characters. ThistoStringmethod is like theIntegerclass’sparseIntmethod. I introduce the

I introduce the parseIntmethod in Chapter 11.

To debug an applet, you can put calls to System.out.println in the applet’s code. If you use Eclipse, the println output appears in Eclipse's Console view.

Responding to Events in an Applet

This section has an applet with interactive thingamajigs on it. This applet is just like the examples in Chapter 15. In fact, to create Listing 16-7, I started with the code in Listing 15-1. I didn’t do this out of laziness (although, heaven knows, I can certainly be lazy). I did it because applets are so much like Java frames. If you take the code for a frame and trim it down, you can usually create a decent applet. This section's applet lives in Listings 16-6 and 16-7.

Listing 16-6: A Guessing Game Applet

import javax.swing.JApplet;

public class GameApplet extends JApplet {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

public void init() {

setContentPane(new GamePanel());

}

}

Listing 16-7: The Guessing Game Panel

import java.awt.Color;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.util.Random;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JTextField;

class GamePanel extends JPanel implements ActionListener {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

int randomNumber = new Random().nextInt(10) + 1;

int numGuesses = 0;

JTextField textField = new JTextField(5);

JButton button = new JButton("Guess");

JLabel label = new JLabel(numGuesses + " guesses");

GamePanel() {

setBackground(Color.WHITE);

add(textField);

add(button);

add(label);

button.addActionListener(this);

}

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

String textFieldText = textField.getText();

if (Integer.parseInt(textFieldText)

== randomNumber) {

button.setEnabled(false);

textField.setText

(textField.getText() + " Yes!");

textField.setEnabled(false);

} else {

textField.setText("");

textField.requestFocus();

}

numGuesses++;

String guessWord =

(numGuesses == 1) ? " guess" : " guesses";

label.setText(numGuesses + guessWord);

}

}

To run the code in Listings 16-6 and 16-7, you need an HTML file:

<applet code="GameApplet" width=225 height=50></applet>

Figures 16-3 and 16-4 show you what happens when you run this section’s listings. It’s pretty much the same as what happens when you run the code in Listing 15-1. The big difference is that the applet appears as part of a web page in a browser window.

Figure 16-3: An incorrect guess.

Figure 16-4: The correct guess.

Instead of noticing whatever code Listing 16-7 may have, notice what code the listing doesn’t have. To change Listing 15-1 to Listing 16-7, I remove several lines.

- I don’t bother calling

setLayout.The default layout for an applet is

FlowLayout, which is just what I want. If you want info on how

If you want info on how FlowLayoutworks, see Chapter 9. - I don’t call the

packmethod.The

widthandheightfields in the HTML applet tag determine the applet’s size. - I don’t call the

setVisiblemethod.An applet is visible by default.

The only other significant change is between Listings 15-2 and 16-6. Like many other applets, Listing 16-6 has no main method. Instead, Listing 16-6 has an init method. You don’t need a main method because you never need to say new GameApplet() anywhere in your code. The web browser says it for you. Then, after the web browser creates an instance of the GameApplet class, the browser calls the instance’s init method. That’s the standard scenario for running a Java applet.

If you use an IDE such as Eclipse, NetBeans, or IntelliJ IDEA to launch this section’s example, the IDE probably opens the Java AppletViewer automatically. If you don't use an IDE (or if the IDE doesn’t open the AppletViewer), you can launch the AppletViewer manually. The command to launch the AppletViewer is

If you use an IDE such as Eclipse, NetBeans, or IntelliJ IDEA to launch this section’s example, the IDE probably opens the Java AppletViewer automatically. If you don't use an IDE (or if the IDE doesn’t open the AppletViewer), you can launch the AppletViewer manually. The command to launch the AppletViewer is To state things a little less plainly, a class can have either

To state things a little less plainly, a class can have either