26. Creating and Removing DOM Elements

In This Chapter

• Understand how easy it is to use JavaScript to create DOM elements from nothing

• Learn how to clone existing DOM elements as well as remove DOM elements you no longer want

This part may blow you away. For the following sentences, I suggest you hold on to something sturdy:

Despite what my earlier chapters may have led you to believe, your DOM does not have to be made up of HTML elements that exist in markup. You have the ability to create HTML elements out of thin air and add them to your DOM using just a few lines of JavaScript. You also have the ability to move elements around, remove them, and do all sorts of God-like things. Let’s pause for a bit while we let all of that sink in. This is pretty big.

Besides the initial coolness of all this, the ability to dynamically create and modify elements in your DOM is an important detail that makes a lot of your favorite websites and applications tick. When you think about this, this makes sense. Having everything predefined in your HTML is very limiting. You want your content to change and adapt when new data is pulled in, when you interact with the page, when you scroll further, or when you do a billion other things.

In this chapter, we are going to cover the basics of what makes all of this work. We are going to look at how to create elements, remove elements, re-parent elements, and clone elements. This is also the last of our chapters looking directly at DOM-related shenanigans, so get your friends and the balloons ready!

Onwards!

Creating Elements

Like I mentioned in the introduction, it is very common for interactive sites and apps to dynamically create HTML elements and have them live in the DOM. If this is the first time you are hearing about something like this being possible, you are going to love this section!

The way to create elements is by using the createElement method. The way createElement works is pretty simple. You call it via your document object and pass in the tag name of the element you wish to create. In the following snippet, you are creating a paragraph element represented by the letter p:

var el = document.createElement("p");

If you run this line of code as part of your app, it will execute and a p element will get created. If you assign the createElement call to a variable (el in our case), then the variable will store a reference to this newly created element. Now, creating an element is the simple part. Actually raising it to be a fun and responsible member of the DOM is where you need some extra effort. You need to actually place this element somewhere in the DOM, for your dynamically created p element is just floating around aimlessly right now:

The reason for this aimlessness is because your DOM has no real knowledge that this element exists. In order for an element to be a part of the DOM, there are two things we need to do:

1. Find an element that will act as the parent

2. Use appendChild and add the element you want into that parent element

The following highlighted line shows both of these steps in action:

<h1 id="theTitle" class="highlight summer">What's happening?

</h1>

<script>

var newElement = document.createElement("p");

newElement.textContent = "I exist entirely in your

imagination.";

document.body.appendChild(newElement);

</body>

Our parent is going to be the body element, which I access via document.body. On the body element, we call appendChild and pass in an argument to our newly created element, to which I hold a reference with the newElement variable. After these lines of code have run, your newly created p element will not only exist but also be a card-carrying member of the DOM.

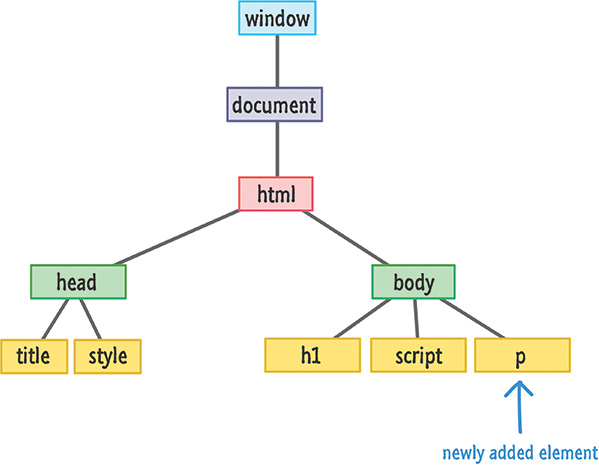

The following is a visualization of what the DOM for our simple example looks like (assume we also have a head, title, and style element in the markup defined):

Now, one thing to note about the appendChild function is that it always adds the element to the end of whatever children a parent may have. In our case, our body element already has the h1 and script elements as its children. The p element gets appended after them as the youngest child. With that said, you do have control over the exact order where a particular element will live under a parent.

If you want to insert newElement directly after your h1 tag, you can do so by calling the insertBefore function on the parent. The insertBefore function takes two arguments. The first argument is the element you want to insert. The second argument is a reference to the sibling (aka child of a parent) you want to precede. Here is our example modified to have our newElement live after your h1 element (and before your script element):

<h1 id="theTitle" class="highlight summer">What's happening?</h1>

<script>

var newElement = document.createElement("p");

newElement.textContent = "I exist entirely in your

imagination.";

document.body.insertBefore(newElement, scriptElement);

</script>

</body>

Notice that I call insertBefore on the body element and specify that newElement should be inserted before our script element. Our DOM in this case would look as follows:

You might think that if there is an insertBefore method, there must be an insertAfter method as well. As it turns out, that isn’t the case. There isn’t a widely supported built-in way of inserting an element AFTER an element instead of before it. What you can do is trick the insertBefore function by telling it to insert an element an extra element ahead. That probably makes no sense, so let me show you the code first and explain later:

<body>

<h1 id="theTitle" class="highlight summer">What's happening?</h1>

<script>

var newElement = document.createElement("p");

newElement.textContent = "I exist entirely in your

imagination.";

var h1Element = document.querySelector("h1");

document.body.insertBefore(newElement, h1Element.

nextSibling);

</script>

</body>

Pay attention to the highlighted lines, and then take a look at the following diagram, which illustrates what is happening:

The h1Element.nextSibling property references the script element. Inserting your newElement before your script element accomplishes your goal of inserting your element after your h1 element. What if there is no sibling element to target? Well, the insertBefore function in that case is pretty clever and just appends the element you want to the end automatically.

Removing Elements

I think somebody smart (probably Drake?) once said the following: That which has the ability to create, also has the ability to remove. In the previous section, we saw how you can use the createElement method to create an element. In this section, we are going to look at removeChild which, given its slightly unsavory name, is all about removing elements.

Take a look at the following example:

<h1 id="theTitle" class="highlight summer">What's happening?</h1>

<script>

var newElement = document.createElement("p");

newElement.textContent = "I exist entirely in your

imagination.";

document.body.appendChild(newElement);

</script>

</body>

The p element stored by newElement is being added to our body element by the appendChild method. You saw that earlier. To remove this element, we call removeChild on the body element and pass in a pointer to the element we wish to remove. That element is, of course, newElement. Once removeChild has run, it will be as if your DOM never knew that newElement existed.

The main thing you should note is that you need to call removeChild from the parent of the child you wish to remove. This method isn’t going to traverse up and down your DOM trying to find the element you want to remove. Now, let’s say that you don’t have direct access to an element’s parent and don’t want to waste time finding it. You can still remove that element very easily by using the parentNode property as follows:

<h1 id="theTitle" class="highlight summer">What's happening?</h1>

<script>

var newElement = document.createElement("p");

newElement.textContent = "I exist entirely in your

imagination.";

document.body.appendChild(newElement);

</script>

</body>

In this variation, I remove newElement by calling removeChild on its parent by specifying newElement.parentNode. This looks like a roundabout method, but it gets the job done.

Besides these minor quirks, the removeChild function is quite merciless in its efficiency. It has the ability to remove any DOM element—including ones that were originally created in markup. You aren’t limited to removing DOM elements you dynamically added. If the DOM element you are removing has many levels of children and grandchildren, all of them will be removed as well.

Cloning Elements

This chapter just keeps taking a turn for the weirderer the further we go into it, but fortunately we are at the last section. The one remaining DOM manipulation technique you need to be aware of is one that revolves around cloning elements where you start with one element and create identical replicas of it:

The way you clone an element is by calling the cloneNode function on the element you wish to clone along with providing a true or false argument to specify whether you want to clone just the element or the element and all of its children.

Here is an example that makes sense of the previous sentence with the relevant lines highlighted:

<html>

<body>

<div id="outerContainer">

<div>

<h1>This one thing will change your life!!!</h1>

</div>

</div>

<div id="footer">

<div class="share">

<p>Something</p>

<img alt="#" src="blah.png"/>

</div>

</div>

<script>

var share = document.querySelector(".share");

document.querySelector("#footer").appendChild(shareClone);

</script>

</body>

</html>

Take a moment to understand what is going on here. The share variable gets a reference to the div whose class value is share. In the next line, we clone this div by using the cloneNode function:

var shareClone = share.cloneNode(false);

The shareClone variable now contains a reference to the cloned version of the div stored in the share variable. Note that we are calling cloneNode with an argument of false. This means that only the div referenced by share is cloned.

The postoperative steps after calling cloneNode are identical to what you would do with createElement. In the next line, we are simply appending our cloned element to the footer div element so that it actually finds mention in the DOM. The DOM for all of this after our code has run looks as follows:

Notice that our cloned element now appears as a peer of the existing div element. The thing to also notice is that this cloned element contains all of the attributes that the original/source element had. For example, this div will also have a class value of share. Keep that in mind when you are cloning elements that contain id values set on them. Because id values need to be unique in the DOM, you may need to do some extra cleanup work to ensure the uniqueness is maintained.

We are almost done here. The last thing to look at is what happens when we call cloneNode and specify that the children get cloned as well. Let’s change our earlier behavior by passing in a true instead of a false in our cloneNode call:

var shareClone = share.cloneNode(true);

When the code runs now, the end result of this minor change is that our DOM will now have a few more people in it because the children of the .share div will also be brought along:

See, told you!!! The p and img elements have also been cloned and dragged along with the parent .share div. Once your cloned elements have been added to the DOM, you can then use all the tricks you’ve learned to modify them.

Tip

Tip

Just a quick reminder for those of you reading these words in the print or e-book edition of this book: If you go to www.quepublishing.com and register this book, you can receive free access to an online Web Edition that not only contains the complete text of this book but also features a short, fun interactive quiz to test your understanding of the chapter you just read.

If you’re reading these words in the Web Edition already and want to try your hand at the quiz, then you’re in luck – all you need to do is scroll down!