1

INVESTING IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM: THE BAGEL AND THE DOUGHNUT

Sunday Breakfast Club of Philadelphia

January 5, 2000

MY TITLE IS INSPIRED by William Safire's essay, “Bagels vs. Doughnuts,” published just a few months ago in The New York Times. These baked goods, Safire tells us, are similar in shape but different in character: Bagels are “serious, ethnic, and hard to digest. Doughnuts are fun, crumbly, sweet, and fattening. … The triumph of bagelism in the 1980s and early 1990s meant that tough munching was ascendant; the decline of doughnutism meant that soft sweetness was in trouble.” But, Safire commiserates, the doughnut is coming back into the mainstream. Why? Because, with the advent of—Heaven forbid!—the blueberry bagel and the bagel sandwich, “the bagel has moved toward the center, its crust going soft and spongy, and lost its distinctive hard-boiled nature.”

Well, surprising as it may seem, in all of this food for thought (pun intended), I find a message about bagels and doughnuts in each of the three subjects on which I'd like to reflect with you this evening, a year before the start of the new millennium, which, as only a killjoy would point out, doesn't begin until January 1, 2001: (1) The outlook for the stock market; (2) the coming change in the mutual fund industry; and (3) the challenges faced by Vanguard—the enterprise I founded on September 24, 1974, just over a quarter-century ago—as the new century begins.

1. The Bagel and the Doughnut in the Stock Market

During the final two decades of the 20th century, the U.S. stock market has provided the highest returns ever recorded in its 200-year history—17.7% per year, as stock prices have doubled every four years. What have been the sources of this unparalleled growth? Well, complex and mysterious as the stock market may seem, its returns are determined by the simple interaction of just two elements: investment returns, represented by dividend yields and earnings growth; and speculative returns, represented by changes in the price that investors are willing pay for each dollar of earnings. It's that simple. It really is!

It is hardly farfetched to consider that investment return is the bagel of the stock market. The investment returns on stocks reflect their underlying character, nutritious, crusty and hard-boiled. By the same token, speculative return is the spongy doughnut of the market. The speculative returns on stocks represent the impact of changing public opinion about stock valuations, from the soft sweetness of optimism to the acid sourness of pessimism. The bagel-like economics of investing are almost inevitably productive. Corporate earnings and dividends have provided a steady underlying return over the long pull, the result of the long-term growth of productivity and prosperity in our resilient American economy. But the flaky, doughnut-like emotions of investors are anything but steady—sometimes productive, sometimes counterproductive. Price-earnings ratios may soar or they may plummet, reflecting wide swings in investor valuations of the economy's future prospects.

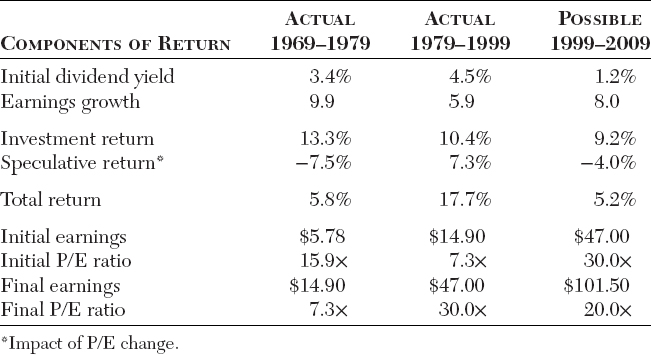

Over the past two decades, the investment returns on stocks have been solid. The initial dividend yield contributed a generous 4.5% to returns, and earnings growth set a good, but hardly remarkable, pace of 5.9% annually. Combining the two produced a fundamental return of 10.4%, closely in line with the 11% nominal return on stocks over the long term. But the speculative return was larger than either of those two fundamental elements of investment return. The market's price-earnings ratio rose from 7.3 times as 1980 began to 30 times as year 2000 begins, a rise that, spread over two decades, has contributed another 7.3% per year, the laboring oar in carrying the total return of the market to 17.7% annually. (See Table 1.1.)

If we cumulate these figures, the twenty-year return on the Standard & Poor's 500 Index came to +2500%. Just 600 points—one-fourth of this gain—were accounted for by investment fundamentals; the other 1900 points represented the pendular swing from pervasive pessimism to overpowering optimism on the part of investors. Put another way, more than three-quarters of the cumulative increase in stock prices during this great bull market has simply reflected a sea change in public opinion about the future prospects for common stock returns, as price-earnings ratios more than quadrupled.

Now of course both history and common sense tell us that price-earnings ratios cannot rise forever. In the decade of the 1970s, for example, the price-earnings ratio fell by more than 50%, from 16 times to 7.3 times, an annual drag of −7.5% that reduced the 13.3% fundamental return generated by earnings and dividends to just 5.8% per year. Yet ironically, that bagel of investment fundamentals—dividend yield of 3.4% and annual earnings growth of 9.9%—produced almost 30% more nutrition than the 10.4% investment return of the next two decades of soaring stock prices. The overriding difference between the inadequate 1970s and the golden 1980s and 1990s, then, was not better bagelism, but the swing of doughnutry from the sweetness of optimism to the sourness of pessimism in the 70s, and then back again in the 80s and 90s, to the greatest sweetness the market has ever recorded.

As we come to consider the outlook for the stock market in the first decade of the new millennium, we need answers on only two questions: Will the bagel of investment fundamentals give us its usual sustenance? And will the doughnut of speculation get even sweeter than it is today, or will it finally sour again? As to the fundamentals, please realize that we begin the decade with far less sustenance than when the bull market began. For the dividend yield on stocks is at an all-time low of just over 1%, meaning that it will take earnings growth of more than 9% to provide a fundamental return equal to the 10.4% total of the past two decades. I think that's too optimistic. But 8% growth maybe possible, given the revolution—and it is indeed no less than that—now taking place in global technology, communications, and productivity. We are clearly in a New Era for the economy.

Whether we are in a New Era for investing, however, is a far different question. If we are to have a continuation of 17%-plus returns—which, polls tell us, represent the public expectation—the doughnut of speculation will have to soar even beyond today's unprecedented peak of sweetness. To get there, assuming a fundamental return of 9.2% (1.2% yield and 8% earnings growth), the market's price-earnings ratio would have to rise from 30 times today to 67 times a decade from now. I simply can't imagine that happening.

Confession being good for the soul, however, I admit that a decade ago, I made a similar analysis of the market, and I was wrong. My fundamentals were about right—my projection of an investment return of 9.7% per year for the 1990s was remarkably close to the actual figure of 10.5%. But I guessed that the price-earnings ratio might ease back from 15.5 times to its then-historic-norm of 14 times. While, happily, I urged investors to maintain their equity positions, I waited and watched the price-earnings ratio rise, as we now know, to 30 times, more than double that figure, making my midrange projection of 9% stock returns—and even my optimistic projection of 13%—seem stodgy. Clearly history doesn't always repeat! And even if one believes that reversion to the mean in market returns will inevitably take place, it can take a long, long time to do so. As I reminded investors then—and I remind you tonight—be leery of projections, whether founded in reasonable expectations or just picked out of the proverbial hat. Anything can happen in the stock market.

But with that caution in mind, I'll nevertheless combine my (decidedly optimistic) fundamental forecast of 9.2% with a forecast that today's speculation will retreat from the market's heady optimism to something considerably less exuberant. Should the current price-earnings ratio ease back to 20 times—hardly bearish—the fundamental return would be reduced by −4.0% annually to bring the market return to 5.2% per year—well short of the 7.5% to 8% available on a high-grade bond portfolio today. That scenario would be a rare one, for bonds have outpaced stocks in but one of every six past decades. But it could easily happen in the coming decade. Only time will tell.

For whatever comfort—or discomfort—it's worth, my views are very close to those of the estimable Warren Buffett. In October's Fortune magazine, using a somewhat different methodology, he suggested 6% as a reasonable expectation for stock returns over the next decade. It's nice to find myself in such good company. But I hardly need warn you that the fact that Mr. Bogle and Mr. Buffett agree doesn't prove anything. Nonetheless, following two decades of record-setting market returns, it would be hard to be shocked by—or even dissatisfied with—a third decade that witnesses some consolidation of past gains. And if we face a decade in which we enjoy a continuation of the solid sustenance of the bagel, but without the added sweetness of the doughnut, I, for one, would count my blessings.

2. The Bagel and the Doughnut in the Mutual Fund Industry

In an environment of lower equity market returns, however, the mutual fund industry will not count its blessings. For lower market returns are the industry's bane. The extraordinarily high stock returns generated in the great bull market that has happily persisted for close to two full decades have blessed this market-sensitive industry, which is among the fastest growing of all American industries during the past twenty years. Since 1980 began, fund assets have risen nearly 70-fold, from less than $100 billion to some $6.5 trillion. Assets of stock funds alone, now almost $4.0 trillion of the total, have risen 120-fold.

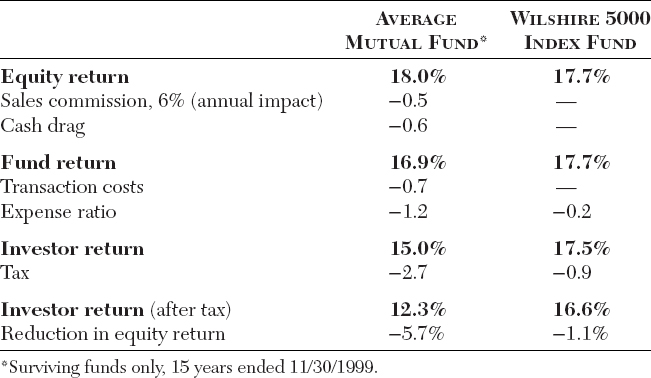

While the rising market tide has lifted nearly all mutual fund boats, very few equity funds have provided their shareholders with anything like the generous returns offered by the market. Indeed of the 426 fund boats that began the voyage 15 years ago, 113—nearly one of every four—have sunk along the way, despite the absence of even one protracted market storm. Fair weather for the market, yes, but foul weather for most funds. Still, the average diversified stock fund that survived the period—obviously excluding the poorer performers—provided an after-tax return of just 12.3%, compared to the 17.7% return of the stock market itself. Final value of $10,000 invested at the outset: total stock market, $115,000; average mutual fund, $57,000.

What was the problem? Simply this: in their frenetic search for sweet, fattening returns, the mutual fund doughnuts levied heavy sales charges, charged excessive fees, spent too much on marketing, and failed to share the economies of scale with the investors they were responsible to serve. On average, equity fund operating expenses and management fees cost some 1.2% of assets annually (they're now more than 1.5%); sales charges cost some 0.5%; and funds paid an opportunity cost of 0.6%, simply because funds were not fully invested in stocks as the market rose. That's a total hit to return of 2.3%.

But that's only the beginning. The doughnut-like mutual funds, ever-searching for the market's sweet spots, turn over their portfolios at an astonishing rate of 90% per year—clearly short-term speculation, not long-term investing. The cost of executing these transactions came to an estimated 0.7% per year. (Funds don't disclose this hidden cost.) And while all of that turnover has failed to add any value whatsoever to the returns of fund shareholders as a group, it has surely enriched the federal government, as taxes cost fund investors an estimated 2.7% of return per year. The combined transaction and tax costs: 3.4% per year. Hardly surprisingly, the surviving funds as a group appeared to be slightly above-average stock pickers, earning an estimated return of 18.0%. However, because of all-in annual costs of 5.7%, their return crumbled to just 12.3% for their owners. Contrary to the entirely reasonable expectations of their shareholders, the sinfully sweet and apparently addictive fund doughnuts failed abjectly to fatten their returns. (See Table 1.2.)

But this industry is not composed solely of doughnuts. There are some—but very few—fund bagels, maintaining the hard-crusted, long-term-focused, low-cost character that was in fact this industry's hallmark when I first analyzed it 50 years ago in my senior thesis at Princeton University. In its purest manifestation—no blueberry here!—the fund bagel is the market index fund. Stripped of all the proffered sweetness of mutual fund doughnutry, the index fund offers the ultimate in character—the broadest possible diversification, the lowest possible cost, the longest time horizon, and the highest possible tax efficiency. Simplicity writ large!

At the outset of the great bull market, there was but a single one of these hard bagels in the entire soft doughnut-filled fund bakery. The first index mutual fund was founded in 1975, designed simply to own the 500 stocks in the Standard & Poor's 500 Index, and hold them as long as they remain there. The second index fund wasn't introduced until 1984, after the lapse of nine years. But the idea behind this bagel-like manifestation of fund investment strategy—own the market and hold it forever—has finally moved from heresy to dogma.

That idea, simply put, is to capture almost 100% of the market's annual return simply by owning all of the stocks in the market and holding them forever, all the while operating at rock-bottom cost. Since the 500 giant corporations of the Standard & Poor's 500 constitute more than three-quarters of the market's total capitalization, the first index fund substantially captured this concept. Recognizing that the remaining one-quarter of the stock market includes corporations with medium-sized and small market capitalizations, and that owning the entire market is an even better idea, the first total stock market index fund was founded in 1992. It is modeled on the Wilshire 5000 Index, now encompassing the more-than-8000 publicly held corporations in the United States.

I recognize, of course, the irony that the all-market index fund delivers so much but appears to offer so little. It can be accurately described as a fund that, because of its expenses—tiny as they are—rises slightly less than the market in good times, declines slightly more in bad times, and will never quite capture 100% of the market's long-term return. But it works. Before taxes, the all-market index fund provided 99% of the market's annual 17.7% annual return during the past 15 years, while the average fund captured just 85%. After taxes, the investor selecting a diversified stock fund at the outset in 1984 proved to have just one chance in 33 of outpacing the all-market fund by as little as a single percentage point on an annual basis. Like looking for a needle in a haystack, you say? Of course. So what is the alternative? Just buy the entire market haystack.

The all-market index mutual fund is the industry's consummate bagel, tough and crusty, serious and, above all, a blessing to the investor's wealth. The traditional managed mutual fund is the industry doughnut, fun, sweet, and crumbly to be sure, and looking swell in all of those chocolate-covered, as it were, mutual fund advertisements you see (and pay for) on television. But it has proved to be anything but fattening to investors’ wallets. In fact—bereft of the kind of mandatory federal health warning-label carried on cigarette packs and liquor bottles—the typical equity mutual fund has proved dangerous to the wealth of investors who succumbed to its sugary smiles. Over the past 15 years, remember, after all expenses and federal taxes, $10,000 invested in the average mutual fund doughnut has grown to $57,000. By contrast, the all-market fund bagel has grown to $100,000. The bagel rewarded the investor with nearly double the reward of the doughnut. Looked at another way, the all-market bagel provided 87% of the stock market's return after all costs and taxes, compared to just 48% for the average stock fund. (See Figure 1.1.)

It takes no brilliance to recognize that many fund investors are delighted to have made a $47,000 profit on their $10,000 stake. They don't realize they might have made a $90,000 profit simply by investing in the market and then doing absolutely nothing. But if I'm correct that the doughnut of market speculation that has driven returns upward in the past two decades will lose some of the sweetness in the years ahead, the mutual fund doughnuts will find themselves in a bad spot. For the lower the market return, the bigger the bite taken by fund costs. If the annual stock market return falls to 5.2%, fund all-in costs of even 2.5% would confiscate nearly one-half of the market's return, reducing the fund investor's return to 2.7%. While the fund bagels would hardly shine in this environment, they would at least produce a 5% return, generous by comparison.

3. Vanguard in the New Millennium: The Bagel in a Doughnut-Dominated Industry

I'm sure this audience of investment-savvy citizens of the Greater Philadelphia region is well aware that the great bagel in the doughnut-dominated mutual fund industry is Vanguard. While Mr. Safire was taking some literary license when he described the bagel-doughnut war as a test of America's national character, it is hardly hyperbole to describe Vanguard's pioneering of bagel-like, market-indexing-type, low-cost investing as a test of the character of a mutual fund industry, an industry heretofore slavishly devoted to the easy—but undeliverable—promise of doughnut-like sweetness in returns.

Safire is appalled by the bakery bagel's attempt at self-destruction—moving toward the center, reaching for an ever-wider audience by compromising its values. Sure, he concedes, sourdough and caraway (may I throw in an “everything?”) are permissible variations, but the blueberry bagel—sweet and soft—reduces a bagel to the level of a stale doughnut. At the same time, the rival doughnut is defiantly reasserting its fattening identity, adding an excess of sweetness and slickness, exemplified by the soon-to-come frosted chocolate “Krispy Kreme,” so Safire tells us. “The bagel, devoid of character and becoming half-baked, seeking to be all pastry to all men, reflects what is wrong with America at the fin de millenaire.”

But the momentum in the fund industry, so far at least, lies with the bagelism of indexing. (Or is it the Bogleism of Vanguard?) While it took years for our rivals to copy our pioneer 500 Index Fund of 1975 and our pioneer Total Stock Market Index Fund of 1992, there are now 332 index mutual funds. While they represent but 10% of equity fund assets, index funds accounted for fully 35% of cash flow in 1999. I, for one, welcome these converts. For if we are to maintain our competitive edge, we need strong rivals who compete with us on the grounds of low investment cost, high-quality service, and giving the investor a fair shake. For while indexing comes at the direct expense, dollar-for-dollar, of the return on capital of the manager, it commensurately enhances the return on capital of the investor.

While our index pioneering was motivated by conviction and missionary zeal, our rivals have been motivated only by the growing public demand for index funds, and dragged kicking and screaming into the fray. Most other index funds, however, are fatally flawed by excessive expense ratios, although some waive their fees for “a temporary period of time,” so as to appear to match Vanguard's low cost. This sort of “bait and switch” strategy (bait the investor, then switch to a higher fee later) may deceive gullible investors for a time, but will not, finally, stand public scrutiny. Emulating a market index is essentially a commodity-like strategy, with the expense ratio the major differentiator. Low costs, simply put, are better than high costs! What is more, the missionary zeal to offer an investment that serves has proven more successful than the reluctant decision to offer a product that sells.

How successful? Today, nearly $250 billion of Vanguard's assets are represented by pure index funds, with another $150 billion invested in high-quality, low-cost, defined asset-class bond and money market funds—$400 billion of our $535 billion total that is clearly dedicated to the bagel mandate. And most of our remaining funds are also bagel-like; that is, they offer clearly specified strategies, exceptionally low costs, and portfolio turnover that is modest by industry standards. To be fair, we have some—albeit far too few—competitors that can fairly be characterized as bagel-like in nature. But the overwhelming majority of mutual funds clearly meet the doughnut definition. And so the great bakery confrontation is joined. May the concept that provides the most financial nutrition for investors win!

In that confrontation, I remain, not on the sidelines, but in the heat of the battle. I begin the year 2000 just as I have begun every year since 1975: Ready to serve the Vanguard shareholders—now eight million in number—arm-in-arm with my fellow crewmembers—now 10,500 strong. In my role as Vanguard's Founder, I continue to act as ambassador to our crew and our owners; in my role as President of Vanguard's newly created Bogle Financial Markets Research Center, I continue to pursue my career-long mission with the enthusiasm and energy that only a now-29-year-old heart could muster. (“Thanks,” to my guardian angels at Hahnemann Hospital!) My research, writing, and speaking come from a perspective that is without parallel in this industry, and my first two books, published in 1993 and 1999, will be followed by two more in 2000, with at least three more on the drawing board.

Many shareholders have asked: “What about Vanguard post-Bogle?” I can only answer: “Don't worry.” First, I expect to be around Vanguard in body for as far ahead as I can see today, energetically pursuing my work. Second, I also expect to be around my firm in soul for as long as the simple investment principles and basic human values that I've invested in Vanguard make sense. As I said to our shareholders in my message in this year's fund annual reports, those principles and those values are not only enduring, but eternal.

Recently, a management consultant applied Emerson's aphorism, “an institution is the lengthened shadow of one man,” to Vanguard. I simply don't believe it. None of what we have accomplished is one man's work; all is the result of a dedicated crew working together for the common good. Our managers and crew are strong; with each passing day, they are gaining experience and, I hope, wisdom. What is more, each passing day reaffirms the worthiness of the principles and values that are so much a part of my very spirit.

Happily, what I have strived for with missionary zeal all of these years has also proved to be a winning business formula. Not only has our strategy been singled out for praise by academics such as Harvard Business School strategic guru Michael Porter, it has also won for Vanguard an ever-growing market share in an industry that “just doesn't get it” when the job is to give mutual fund investors a fair shake. Responding to our challenge as the 2000s begin, some of our rivals are finally starting to get the business side of it right. But they won't capture the real message until they have, well, a change of heart, placing above all other values, not the marketing of financial products, which is what doughnutry is all about, but the stewardship of investor assets, the central principle of bagelism.

HMS Vanguard will flourish so long as we stay the basic course we have set for ourselves—not, to be sure, blindly or complacently, but open always to midcourse corrections in the face of the sea changes now occurring in every activity on the globe in this truly new era of information, technology, and communications. Nonetheless, having stripped the mystery from investing, exposed the importance of cost, earned rather than bought our market share, propounded the essentially long-term character of successful investing, and held high the mission of stewardship, Vanguard must avoid at all costs emulating the periodic attempts of our rivals to pander to the fads and fashions of the day, even if it causes our vaunted market share—Heaven forfend!—to slip for a while. In the long run, staying the course will carry the day.

In that light, after I read Mr. Safire's October essay, I dispatched copies of it to each of Vanguard's 200 officers, with the hope and expectation that it would be circulated widely among our crew members. My aim was to warn them of the dangers of adopting even a hint of the doughnut's lightness, softness, and sweetness, and to remind them of our commitment to the bagel's hard-hitting and uncompromising standards, its crusty and nutritious character. The three lessons Safire cites in “Bagels vs. Doughnuts” are poignant for any enterprise, and remarkably relevant for Vanguard.

- When you score a breakthrough and surge far ahead, never forget the reason for your success. In the bagel's case, that reason was a certain quality of tasty toughness against a crumbling opposition of sustained sweetness.

- When you open up a long lead against the competition, never let up and freeze the case, lest hungry runners-up eat your lunch.

- When greed for an ever-growing market share causes you to sacrifice your authenticity and compromise core principles, repent and take a stand—or your flavor will disappear into the mealy maw of moderation.

Put another way, Vanguard must—and we will—protect our brand name with our actions, and let our rivals use their own bland names to seek their own destinies in their own ways. Quoting Safire for the final time, “Let doughnuts be doughnuts, let bagels be bagels. Character counts. Authenticity attracts.” I have not the slightest doubt that Vanguard—not only while I live here on earth, yes, but when I live beyond some far horizon, too—will maintain its character. The stamp of authenticity that Vanguard investors have come to rely on is here to stay.