2

THE CLASH OF THE CULTURES IN INVESTING: COMPLEXITY VS. SIMPLICITY

Keynote Speech

The Money Show

Disney Coronado Springs Resort, Florida

February 3, 1999

I’M DELIGHTED to have the opportunity to present this keynote address to this awesome throng of 9,000 individual investors. Given the opportunity to do so in this landmark centennial year, I want to focus your attention on a landmark theme: The clash of two cultures in investing: complexity and simplicity. As the creator of a mutual fund firm that has, since its inception almost 25 years ago, been the apostle of simplicity, I'm confident that you will be less than astonished at which side I shall take in this debate.

Now, I am well aware that much of The Money Show's appeal is based on complexity. Essentially, the thesis presented here is that there are various kinds of complex financial strategies, systems, and investments that will enable you to overcome the awesome odds against beating the market, and that there are various individuals who have clear insights into what the future—be it a new era or the apocalypse—will hold for financial assets.

I count that you'll have the opportunity to attend roughly 130 different seminars, masterminded by more than 100 speakers. Remarkable! It looks to me as if the great preponderance of them will offer you their secrets for success in the new millennium (which, not to be a purist, but facts are facts, will begin not on January 1, 2000, but on January 1, 2001). Many speakers will offer you tempting solutions involving at best complexity, and at worst financial legerdemain and witchcraft.

I must confess that (no offense intended to the presenters) I wince when I see so many subjects that seem to offer easy roads for you to build your capital: “Wealth Creation and Preservation: Increasing Yields to 15–20%,” “The Possible Trillion Dollar Opportunity of the Internet,” “Finding Your Future Wealth in Diamond Mines,” “High-Profit Low-Risk Strategies,” “The 10 Top Funds of 1999,” “Finding the Next Super Stock,” “Index Funds: Making Handsome Returns in Bull and Bear Markets,” and “Five Ways to Beat the Standard & Poor's 500.” (Just for the record, presented by a newsletter which, since its inception seven years ago, has lagged the S&P 500 by the awesome margin of 64 percentage points!)

I assume from the titles that these speakers will offer you the secrets of success. Let me offer mine: the one great secret of investment success is that there is no secret. My judgment and my long experience have persuaded me that complex investment strategies are, finally, doomed to failure. Investment success, it turns out, lies in simplicity as basic as the virtues of thrift, independence of thought, financial discipline, realistic expectations, and common sense. And I am heartened by the fact that at least one panel may be operating on my wavelength. So I endorse without reservation: “Investing Made Simple: How to Simplify your Life and Increase Your Return.”

Let's now examine the issue of complexity. I'll begin with some quotes from a man whom I have never met, but for whom I have great respect. Warren Buffett's esteemed and acute partner at Berkshire Hathaway Inc., Charles T. Munger, puts the case against complexity this way:

Complexity is the direction taken … by many large foundations and college endowment funds, with not few but many investment counselors, chosen by an additional layer of consultants to decide which are best, relying on security analysts paid seven-figure salaries by investment banks, and including foreign securities in their portfolios, … trying to emulate Bernie Cornfeld's fund-of-funds. There is one sure thing about all this complexity … the total cost can easily reach 3% of assets. People are ridiculously over-optimistic [if they expect that they can make up] what these croupiers take.

Mr. Munger goes on to point out the devastating impact of the cost of all of this complexity on the returns of foundations and endowments in a stock market with lower returns: Market return, 5%; total cost, 3%; net return, 2%. Payout to beneficiaries, 5%; net annual loss of capital, 3%. If we extend this analysis out for a decade, the capital wealth of the endowment falls by 26%; over two decades by 46%; after three decades by 60%. (Please don't scoff at the use of the 5% return on stocks. The long-term real return on stocks has been 7%, so Mr. Munger's hypothetical future figure is far from apocalyptic.)

The investor who owns a portfolio of mutual funds would, I hasten to add, be in precisely the same boat. Once retirement comes, you will depend on your accumulated capital to provide you with monthly income, indeed income that must grow in an amount sufficient to protect you against rising living costs. In today's financial markets, with common stocks yielding less than 1½% and high-grade corporate bonds yielding but 6%, make no mistake about it: Income alone, with all of its stability and predictability, will not do the job. Capital, with all of its volatility and unpredictability, will have to help create your returns. What is more, mutual funds will make the job tougher for you. For funds, or at least most of them, are among the most income-unfriendly investment vehicles ever created. Today, the average stock fund has a yield of only 4/10ths of 1%, and the average corporate bond fund must now have a true yield of only 5%.

What does the past tell us about the complex investment strategies that entail selecting winning mutual funds? Over and over again, it sends the same message: Don't go there. (Why? Because using Gertrude Stein's inspired phrase, “there is no there there.”) No matter where we look, the message of history is clear. Selecting funds that will significantly exceed market returns, a search in which hope springs eternal and in which past performance has proven of virtually no predictive value, is a loser's game. To make the point, let's consider five examples of funds selected by professionals seeking investment superiority:

- First, the past records of fund managers compared to the stock market.

- Second, the records of investment newsletters, many of which are represented at this Money Show.

- Third, the records of fund advisers chosen by The New York Times.

- Fourth, the record of the “Managers of the Year” selected by Morningstar.

- Fifth, and most dismal of all in this (as it turns out uninspiring) universe, the record of funds-of-funds, which preen about their ability to choose a portfolio of the best funds for you. (The original fund-of-funds, of course, was formed by the aforementioned Bernie Cornfeld. It did not have a pretty burial.)

Successful Fund Managers Fail

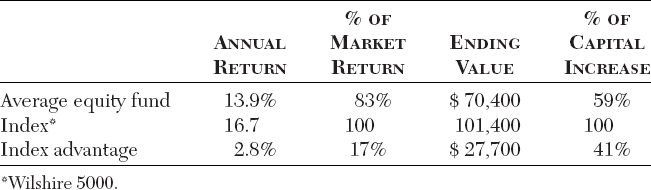

Fund managers, of course, are following what is a complex methodology. They decide on their investment strategy, evaluate individual stocks, try to determine the extent to which a company's stock price may discount its future prospects, and turn their portfolios over with a passion. All of this complexity, however, has failed to produce market-beating returns. In recent years, that fact has become well accepted. Not merely by academics and financial analysts who have been proving that elemental fact since time immemorial, but by the fund industry itself. In the past 15 years, for example, only 42 of the 287 funds that succeed in surviving the period—one out of seven—outpaced the all-market Wilshire 5000 Equity Index (a much less demanding standard during this period than the Standard & Poor's 500 Stock Index). Fully 245 funds failed to do so. What is more, only 10 of the top funds—one out of 29—did so by what the experts describe as a “statistically significant amount”—an amount sufficient to justify their greater volatility. The annual return on the market was 16.7%, for the average fund, 13.9%. So, the funds provided 83% of the market's annual return. During the full period, an investment of $10,000 in the average fund would have grown to $70,400; the stock market itself to $101,400. The added capital accumulated by the funds was but 59% of the market's accumulation. The fund industry itself consumed 41% of its shareholders’ potential capital. It must have been figures like these that persuaded one former fund chief executive to concede recently that equity mutual funds can “never” (his word) beat the market, and Peter Lynch to admit that “most investors would be better off in an index fund.” (See Table 2.1.)

Newsletters Do Even Worse

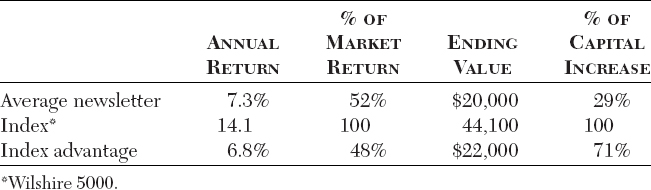

Investment newsletters reinforce the same message, even as they add their own layer of complexity to that of the funds they select. A new study by the Hulbert Financial Digest—and bless Mark Hulbert for his pioneering work—finds that, from the market high in August 1987 through the end of 1998—a fine period for analysis, including as it does both bull and (a few) bear markets—the average fund newsletter provided an annual return of 7.3%, only one-half of the 14.1% return on the Wilshire 5000 Index. Based on $10,000 invested at the 1987 market high, the increase in the value of the index investment would have been $34,100, the increase in the value of the newsletter picks, $10,000—only 29%. The fund managers collected an estimated $2,900 from the funds for their failure, and just a single newsletter cost a cumulative $2,100. Clearly these two sets of croupiers collected $5,000 of the average $15,000 value of the account, or about the apparently customary 3% per year cited by Mr. Munger. The gurus were better rewarded by the market's return than were their subscribers. Only six out of 55 advisers did better than the market; only three—three out of 55—did so when risk was taken into account. All claim, at least implicitly, to provide market-beating returns with their complex multilayered approaches, but precious few delivered on that promise. It would take more confidence than I can muster to even dream that those few will repeat their success in the next long cycle of the market. (See Table 2.2.)

“All the News That's Fit to Print”

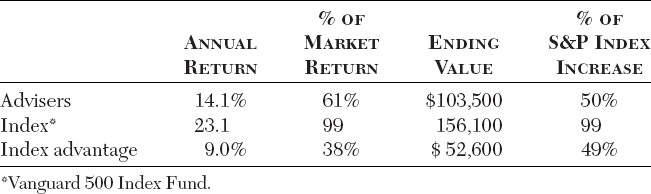

The record hardly improves when we consider the accomplishments, published each quarter, of five investment advisers who, five and one-half years ago, were asked to select and manage hypothetical portfolios for The New York Times based on their own complex methods of evaluation. Since then, the $50,000 that each adviser initially invested has grown, on average, to $103,500. Not bad? Not bad until you realize that the measurement standard set by the Times (the largest S&P 500 Index Fund) grew to $156,100. (With an uncharacteristic lack of candor, the Times did not see fit to print that figure, so I have now done it for them.) Thus, the investor who chose not to use the pros gained an extra $53,000 on his $50,000 initial stake. The advisers earned just 61% of the market's annual return (14% vs. 23%), resulting in only 50% of the extra capital accumulated by the index fund. (See Table 2.3.)

“Manager of the Year”

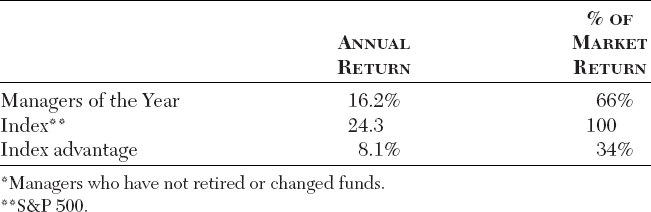

I bow to no man in my respect and admiration for Morningstar Mutual Funds, and, I add hastily, for their courage in having selected, each year since 1987, the equity fund “Manager of the Year” (equivalent, I suppose, to the “superstars” with whom those of you with $49 will be taking an intimate lunch tomorrow). It is a complex task, and the Morningstar editors obviously add a healthy dollop of judgment when they consider the chosen fund's inevitably superior record of past performance. Alas, in investing, such courage is rarely rewarded, and the managers selected through 1997 have, after admittedly brilliant records prior to their selections, quickly turned nondescript. Not a single one of these managers surpassed the S&P 500 Index in the years that followed his selection. The average cumulative annual return for the managers through 1998 was 16.2% vs. 24.3% for the S&P Index. The “Managers of the Year” earned but 66% of the market's annual return. (See Table 2.4.) Let's hope that the “Time-Magazine-Cover-Jinx” doesn't strike the 1998 winner, whose past record, like those of his predecessors, has been truly extraordinary.

TABLE 2.3 The Cost of Complexity, The New York Times Test of Five Advisers ($50,000 Investment: July 1993–Dec. 1998)

Bernie Cornfeld's Successors

I have just one more example: the sad record of funds-of-funds that charge an extra fee for the extra complexity they add to the issue of fund selection—picking advisers to pick advisers, precisely what Berkshire Hathaway's Mr. Munger warned us about. The idea of funds-of-funds is essentially this: given the market-beating returns of so few mutual funds, and the inability of investment newsletters, financial advisers, and even Morningstar to pick winning funds in advance, why not pay professional fund pickers a generous fee and let them do the heavy lifting purportedly involved in beating the market? It seems, on the face of it, a fine idea.

Alas, their record is probably the worst of the lot. The original fund-of-funds, an idea that began with Bernie Cornfeld and collapsed with his entire Swiss-headquartered fund empire, has now attracted some 120 U.S. emulators. Nearly all of them extract an exorbitant annual fee, averaging 1.6% of assets—just for picking funds! With the average fund expense ratio of 1.5%, this add-on more than doubled the direct cost of fund ownership, to a hefty 3.1% Funds-of-funds have failed in two ways. Not only have they failed to pick funds that can outpace the market, but they have failed even to pick funds that can outpace their peers (as we have already learned, a measurably lower standard of accomplishment). (See Table 2.5.)

On average, during the past three years in which their numbers have burgeoned, funds-of-funds that charge fees—there are but a handful that don't—have underperformed 77% of the mutual funds in the large-cap style group. That result suggests that the fund selections by these funds-of-funds are far below what mere random selection would have offered. As a result of the gap caused by both their extra layer of selection complexities and their extra layer of fees, large cap funds-of-funds have provided annual returns of just 17.9%, compared with 19.5% for large-cap mutual funds as a group, and 28.2% for the S&P 500 Index. Providing a mere 63% of the market's annual return is hardly a monument to the doubling of the complexity component that funds-of-funds offer.

Life Is Short. Enjoy! But Only Up to 5%

You must now be as exhausted as I am by the unremitting pounding of the theme that complexity simply doesn't work. What you are seeing at the Money Show, by and large, is also complexity writ large. I have no ability to tell you how it will work in the future, but I can assure you that it hasn't worked very well in the past. To be sure, you'll meet lots of smart, engaging, purposeful financial advisers here. It will be exciting and enticing, but, after all is said and done, you'll find no surefire solutions for investment success—wealth without risk, if you will. It's just not a realistic expectation. But being here is fun, and trying out modern remedies for age-old problems lets you exercise your animal spirits. Given the circumstances, I would encourage you to do exactly that. Life is short. If you want to enjoy the fun, enjoy!

But not with all of your hard-earned resources. Specifically, not with one penny more than 5% of your investment assets. At most! Have the fun of gambling, but not with your rent money—and certainly not with your retirement assets nor with your funds for college education. Perhaps test two or three of the presenters’ recommendations. They may teach you some valuable lessons, and probably won't hurt you too much in the short term. Fun, finally, may be a fair enough purpose for your Funny Money Account. But what, you ask, should you do with your Serious Money Account? How should you invest that 95% of your assets on which you now depend—or will one day depend—for your comforts of human existence?

Now … to the Serious Money Account

Rely on simplicity in setting and implementing strategy for your Serious Money Account. You need not believe me, though I've been at it for a long time. Rely instead on the wisdom of Charles Munger's more renowned partner at Berkshire Hathaway, the legendary Warren Buffett. Best known for his strategy of owning businesses that create long-term value, rather than pieces of paper that his friend “Mr. Market” comes by to bid on every day (to no avail), Mr. Buffett's buy-and-hold strategy is the essence of simplicity, evil complexity's angelic twin. Hear his words:

The art of investing in public companies is … simply to acquire, at a sensible price, a business with excellent economics and able, honest management. Thereafter, you need only monitor whether these qualities are being preserved. Most investors, both institutional and individual, will find that the best way to own common stocks is through an index fund that charges minimal fees. Those following this path are sure to beat the net results (after fees and expenses) delivered by the great majority of investment professionals. Seriously, costs matter. For example, equity mutual funds incur corporate expenses—largely payments to the funds’ managers—that average about 100 basis points, a levy likely to cut the returns their investors earn by 10 percent or more over time.

It will hardly surprise you that I wish to associate myself with each element of Mr. Buffett's position: investing in businesses; using an index fund to do so; and holding costs to bare-bones minimums. In a sense, I take the middle ground between the Munger anti-complexity philosophy (because its 3% cost would confiscate 30% of a 10% long-term stock return) and the Buffett pro-simplicity philosophy (because its 1% cost would confiscate 10% of the return). I believe that the annual cost of equity mutual funds today is upwards of 2% per year—an average annual expense ratio of 1.5% (which you can measure) and an average cost of from 0.5% to 1.0% or more incurred by portfolio turnover (which you can't measure; the fund's adviser can, but he won't tell). This hidden cost is the result of the absurd 85% average annual turnover of fund portfolios. This rate suggests an average holding period of only 1.1 years for the typical portfolio holding. Such short-term speculation is the antithesis of long-term investing—buying businesses, not pieces of paper—which is the cornerstone of the Buffett-Munger strategy.

Why do Mr. Buffett, Mr. Munger, and I all agree on the inherent value of a low-cost market index fund? Simply because of these two brutally obvious facts: (1) All investors as a group must match the market's return before costs. Therefore: (2) All investors as a group must fall short of the market's return by the amount of their costs. Conclusion: Nearly all investors—nearly every human being here in this audience tonight—will fall short of the market's return by an appreciable amount. Yes, it is true. But you can avoid this dire yet predictable fate if you will simply turn from complexity to simplicity. Simplicity in investing begins with setting this standard as your objective:

The realistic epitome of investment success is to realize the highest possible portion of the market returns earned in the financial asset class in which you invest—the stock market, the bond market, or the money market—recognizing, and accepting, that that portion will be less than 100 percent.

How close can you get to 100%? Your best chance is with an index fund. It is the embodiment of simplicity, investing in the entire stock market; diversified across almost every publicly held corporation in America; essentially untouched by human hands; nearly bereft of costly portfolio turnover; remarkably cost-efficient; and extraordinarily tax-effective. Such a fund will provide you with—indeed, virtually guarantee you—98% to 99% of the market's annual return over time, a vast improvement over the 85% or so that the typical mutual fund has provided.

An index fund based on the Wilshire 5000 Equity Index owns 100% of the market, so, in an environment of, say, 12% returns, such a fund, carrying an annual cost of 0.2 of 1%, will provide a return of 11.8%, or 98% plus. Another reasonable choice is an S&P 500 Index fund, which is based on an index that includes 75% of the value of all U.S. stocks. Because of the powerful surge of the large-cap stocks in the Index, the 500 Index fund is the popular favorite of the day, but I do not believe that large-caps, important as they may be in the market's mix, are destined for permanent ascendancy. So a little caution is called for in projecting the past. Small- and mid-cap stocks, the dogs of recent years, will have their day. In the long-run, large- and small-cap stocks are apt to provide similar returns, so either fund should work out just fine. But over the short run, a total stock market index fund will obviously provide a closer tracking of the total market—the quintessential rationale for the theory of indexing.

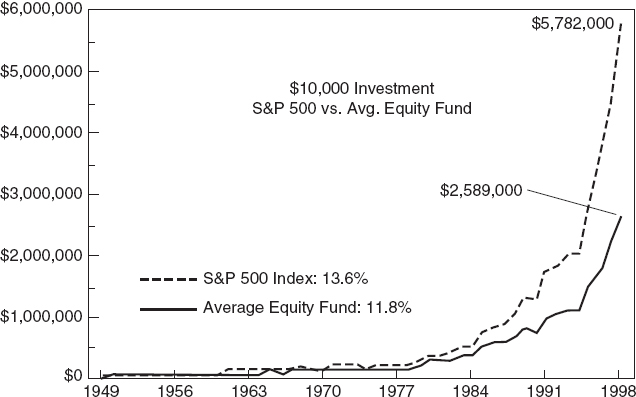

Simplicity Works

Since I have earlier shown you five clear examples of the cost of complexity in investing, let me now show you, with equal clarity, the value of simplicity. The superiority of the passively managed S&P 500 Index has now prevailed for at least a half century. During the past 50 years, the return on the Index has averaged 13.6% per year, a 1.8% margin over the average large growth and income mutual fund. Thus, the average fund has earned 87% of the market's annual return. Given the powerful compounding of returns over this long period, the final value of an initial investment of $10,000 in the 500 Index would be $5,782,000. For the equity mutual fund, the final value would be $2,589,000. Result: The fund provided less than half—45%, to be precise—of the market's accumulation. Table 2.6 and Figure 2.1 show how these assets accumulated over time. (Taxes are ignored; if they were included, the Index advantage would be substantially larger.) The obvious fact: Simplicity works.

It would be easy, I suppose, to say “case closed” at this point. But I owe it to you to point out that the value of the simplicity that is manifested in indexing seems to be growing. Why? Because the cost of owning mutual funds has been rising over the years.

I must quickly add a warning that the huge 4% positive annual margin of the S&P 500 Index during the past decade is unlikely to be repeated. Large-cap stocks have dominated their medium- and small-sized cousins during this period, and such trends, as I noted earlier, typically revert to the market mean over time. But even the 2% to 2½% long-term margin I would expect for the Index would provide another remarkable tribute to the virtue of low-cost simplicity.

In short, the simple—utterly, infinitely simple—concepts of indexing are of surpassing importance in investing your Serious Money Account. By focusing on the long term—always the long term—indexing holds the master key to your investment success. These three final charts beautifully exemplify how time—the fourth and crucial temporal dimension of investing—interacts with reward, risk, and cost, the three spatial dimensions. Do not fail to apply these three simple concepts to the simple idea of index investing.

The Reward Dimension

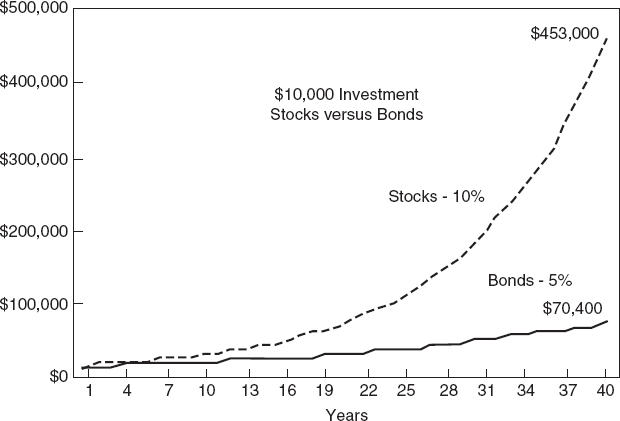

Reward is the first and most important dimension of investing. Time accelerates rewards. “The Magic of Compounding,” encapsulated in compound interest, is truly, as Einstein is said to have noted, the greatest mathematical discovery of all time. Use it to multiply your financial assets by emphasizing equities, but not to the exclusion of bonds. Despite, or perhaps because of the fact that we've enjoyed a sun-drenched environment for 16 years, stormy years have always punctuated the long two-century up-trend in U.S. stocks. But if we can assume future returns of stocks in the 10% range and of bonds in the 5% range, the difference in capital accumulation on a $10,000 initial investment is dramatic: after 40 years, stocks, $453,000; bonds, $70,400. Take advantage of the rewards available in equities, and multiply them by putting time on your side. (See Figure 2.2.)

The Risk Dimension

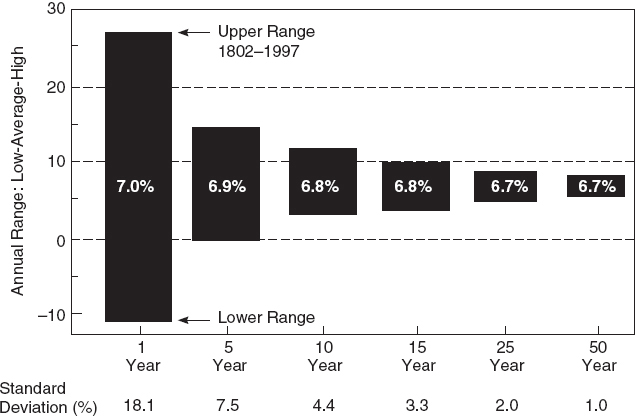

But don't ignore risk, the second dimension of investing. Stocks, especially today, carry high short-term risk. But time moderates risk. It does so in a manner that also seems like magic. We might call it “the moderation of compounding.” The risk in stocks (we use a measure known as standard deviation, which measures the typical range of real returns on stocks), drops by fully 60% (from 18.1% to 7.5%) simply by extending the time horizon from one year to five years. After 10 years, 75% of the risk (the risk measure is now down to 4.4%) has been eliminated. It continues to drop (to 2.0 by 25 years and to 1.0 by 50 years), but the most significant reduction has come within the first decade. No investor should forget, however, that odds should never be mistaken for certainties. Who is to say, really, that we are not facing a decade which will parallel the lowest decade in market history (1964–74), when the annual real return on stocks was −4.1%. (See Figure 2.3.)

FIGURE 2.3 Risk: The moderation of compounding. (Range of real returns and standard deviations, 1802–1997)

The Cost Dimension

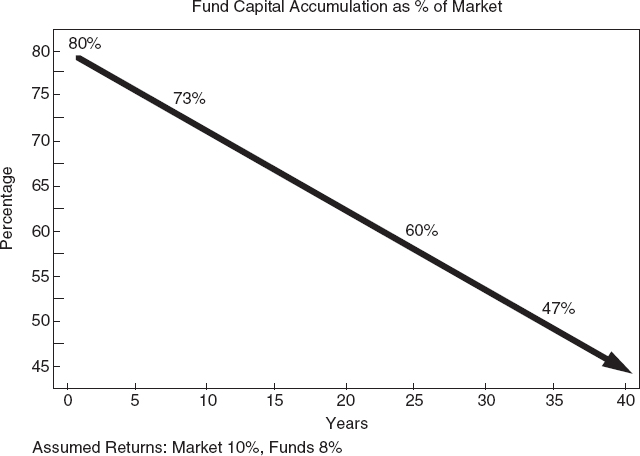

You may have thought a great deal about how time moderates risk and accelerates reward, but if you are like most investors, you haven't thought about the third dimension: Cost. Time magnifies the impact of cost. Almost without your noticing, the costs of investing nibble at your returns, gradually eroding them almost right before your unsuspecting eyes. As the years roll on, costs loom ever larger. We see the same principle at work that creates the magic of compounding, but it works in reverse. I call it “the tyranny of compounding.” If we assume that the stock market provides a 10% long-term return, the average mutual fund will provide an 8% annual return, net of its 2% all-in costs. At the end of a single year, the investor will have accumulated 80% of the market's appreciation. But then cost tyranny rears its ugly head. After five years, the fund accumulation is but 77% of the market's; by 10 years, 73%; and by 25 years, only 60%. And at the end of today's typical 40-year time horizon for a beginning investor, the fund accumulation has fallen to a mere 47% of the market's. (See Figure 2.4.) The mutual fund industry, without putting up a penny of the initial $10,000 investment in stocks, will have consumed more than half of your capital that might have accumulated in the market, as its high costs are extracted from the returns the market earned over the years. Cost matters.

So there you have it. The case for complexity compels the conclusion that the game—fun though it may be—is hazardous to your wealth. The case for simplicity seems, to me and to Charles Munger and Warren Buffett at least, compelling. Low cost, marginal in its annual impact, becomes overpowering as the years roll on. Indexing, by eliminating the risks both of selecting an investment style and selecting a portfolio manager who fails, leaves the investor with the single risk that all investors must incur: market risk. A Funny Money Account, I suppose, has its place—provided it is a tiny place—in investing. We all must, or so it seems, learn by making our own mistakes. But the lesson we finally must, and will learn, is that, for your Serious Money Account, simplicity trumps complexity in the long run.

Clash there may be between the two cultures of investing, but I have no doubt about the final victor. Do you?