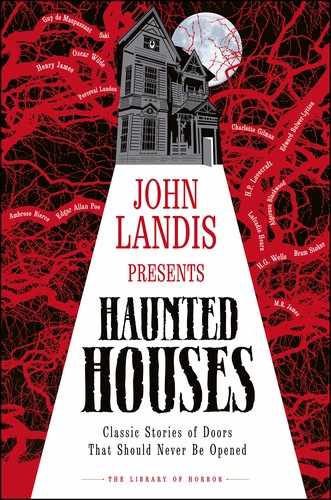

< Contents

There Are Some

Doors That Should

Never Be Opened

Introduction by

John Landis

Have I ever seen a ghost? No, but I may have heard one once. In the early 1970s, my then girlfriend shared a house with three other college students in the Hollywood Hills. The house had four bedrooms, two on the first floor, then two more downstairs, a living room, kitchen, and four bathrooms. I often spent the night in my girlfriend’s room. They employed a housekeeper, a middle-aged woman who came five days a week. One day, when two of the girls arrived home they found their housekeeper hysterical on her way out the front door. When asked what on earth was the matter, she told them that, when entering the kitchen that afternoon, she found a man with a mop of white hair, wearing glasses and a powder blue bathrobe and slippers, sipping a cup of tea. When she asked who he was and what was he doing there, he simply smiled and slowly disappeared. The man dissolved into nothingness in front of her eyes. This apparition terrified her and she was leaving the house as quickly as possible. Hoping to reassure her, the girls went back into the kitchen with her. There was no one there. But there was half a cup of hot tea on the counter.

From that day forward, the housekeeper would not return to clean the house unless someone was home. About two weeks later, another housemate, a man in his mid-twenties named Max, saw someone in the living room when he thought that he was home alone. Max crept closer for a clearer view and sure enough, sitting on the couch was the white haired man with glasses, in his powder-blue bathrobe and slippers, leafing through a magazine. Max ran to his room and locked himself in.

When I arrived home minutes later, Max, breathing heavily, told me there was a strange man in the living room and asked if we should call the police. I asked Max if he had spoken to this mystery man and he said that he had been too scared. I went into the living room. There was no one there. We checked all the doors and windows in the house and they were all locked.

Over dinner that evening, we decided to name our mysterious visitor Andy, after Andy Warhol, who matched the descriptions given by both Max and the housekeeper. Over the next month, everyone who lived in the house had an encounter with Andy. Once, both Max and Anne Marie saw him at the same time in the backyard.

I was only in the house on weekends and I never saw Andy myself. But one lazy Sunday morning, when my girlfriend and I were in bed and alone in the house we heard the front door open and close, then footsteps on the stairs. I opened our door but no one was there. We were home alone.

And that remains my only supernatural experience: I may have heard a ghost.

Have I ever been frightened by a ghost? Absolutely. In books, the theater and the movies I have been scared witless by ghosts. For some odd reason people enjoy being scared—and cinema, literature and the theater are particularly good at scaring us. Many of the stories we tell in books, the stage and the movies are designed to alarm us. Stories that are filled with doors that should never be opened.

Death is such an overwhelming and frightening concept that we cannot and will not accept its finality. A loved one just vanishes? One moment they are with us and then they are gone forever? In a way, it may be oddly comforting to believe in ghosts—after all, ghosts are proof of some kind of life after death. An “Afterlife.”

Ghost stories are a direct challenge to our modern, science-based lives. That’s what makes them so fascinating; our reasonable selves versus the unnatural, the supernatural, and the extraordinary. Ghost stories directly challenge our intellect, our sense of self and mostly... our fear of the unknown. In ghost stories, rationality comes face to face with powerful supernatural events, born of uncanny forces.

And so we come to the topic of Haunted Houses, the unifying theme of the stories in this anthology. Modern moviemakers often place their evil phantoms in suburban dwellings, like the houses in The Amityville Horror, Poltergeist, The Ring, and A Nightmare on Elm Street. These locales tend to be closer to our own contemporary experience. However the architecture of the haunted houses in this collection is largely (but not all) of the traditional, 19th century and earlier variety—crumbling mansions, dark corridors, locked doors, four poster beds, and guttering candles, like in Edgar Allan Poe’s House of Usher. These are places with distinctly checkered pasts, where people have died, terrible acts have been committed, and evil has taken hold. These past evils are demanding to assert themselves into the here and now to our peril.

Haunted house stories can be divided into two basic genres. In the first category, it’s hard to tell whether the ghost or ghosts are genuine or the product of a feverish imagination. These stories are usually told by a narrator who becomes increasingly unreliable as the bizarre events unfold. This category is often the most suspenseful, inexplicable, and disturbing, and some fine examples are presented here in Henry James’ “The Turn of The Screw,” Guy de Maupassant’s “The Horla,” and Charlotte Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” The first of these stories was superbly brought to the screen in 1961 by director Jack Clayton as The Innocents, starring Deborah Kerr as the disturbed and disturbing governess. The film is all the more frightening in that the ghosts (for the most part) are unseen. The same can be said for the invisible presence haunting the narrator of “The Horla,”—adapted into the 1963 movie Diary of A Madman (directed by Reginald Le Borg) starring a melodramatic Vincent Price. In “The Yellow Wallpaper” it’s hard to say whether the female narrator is seeing something supernatural in the wallpaper, or whether she is being “gaslighted” by her overbearing husband into thinking she’s going crazy. Or is she really and dangerously mentally ill? This type of ghost story works particularly well because, as so often in ghost stories, the ghostly activity manifests itself when the main characters are at their most vulnerable—at night, in bed. They may be drowsy, unsure of their mental state or whether they are awake or having a nightmare . . . The genius of Wes Craven’s 1984 movie A Nightmare On Elm Street is that the murderous demon Freddy Krueger literally exists only in your dreams.

The second type of haunted house story is more straightforward. When the characters hear “bumps in the night” they turn out to be chillingly genuine. There is a malevolent presence, usually a dead malefactor of some kind, that wants to take revenge on the living for invading its domain. These ghosts may be slightly less terrifying, unless you happen to be superstitious or the evil presence is particularly vicious, gruesome, or well described. In Percival Landon’s “Thurnley Abbey,” the extremely violent ghost scares the hell out of the owners and their guests. The writers Ambrose Bierce (“The Spook House”) and H. P. Lovecraft (“The Shunned House”) do their darndest to make us uneasy. Of course, not every ghost-story writer is interested in only scaring us. Oscar Wilde in “The Canterville Ghost” gently spoofs the whole idea of ghosts and a haunted house.

A Shakespeare quote from Hamlet neatly sums up why a good many main characters in ghost stories are set up for such a bad time: “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Most of the protagonists in our chosen stories are skeptical, scientifically-minded, or innocent, blundering fools. The scientifically-minded see a haunted house or chamber as a challenge to their intellect and courage. In Edward Bulwer Lytton’s “The Haunted and the Haunters,” a man deliberately chooses to spend the night in a notoriously haunted house that most men would avoid. In H. G. Wells’ “The Red Room,” a skeptical man takes an inn’s haunted room, against wise local advice, and learns to regret it. In Bram Stoker’s “The Judge’s House,” an arrogant math student moves into a house formerly owned by a notorious hanging judge. In H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Shunned House,” the narrator and his uncle resolve to find out whether a creepy, desolate old dwelling where many people have sickened, gone mad, and died, is “unlucky” or genuinely haunted. Whether they come equipped with an array of scientific instruments, armed with a hubristic belief in rationality, or are just sheltering from bad weather, as in Ambrose Bierce’s “The Spook House,” these hapless visitors either depart sadder and wiser after a lucky escape or come to a miserable end.

Some haunted house stories defy easy categorization, such as “The Reconciliation,” Lafcadio Hearn’s version of a Japanese ghost story. This tale was dramatized in one of my favorite Japanese horror films, Masaki Kobayashi’s beautiful and poetic Kwaidan (1964) which tells four of the Japanese folk tales written down by Lafcadio Hearn. The movie version of “The Reconciliation” elaborates on the original story, the Samurai protagonist ends up strangled by his long-dead wife’s black hair!

A haunted house narrative with a difference is Saki’s wicked “The Open Window,” in which a nervous guest is tricked into believing the house where he has come to stay is haunted because of the story the malicious teenage girl who lives there tells him.

Another haunted house story with a difference is M.R. James’ “The Haunted Doll’s House,” in which an antique dealer acquires a dolls house complete with dolls. In the dead of night, the dolls come alive with violent intent.

The stories collected here will convince you that some doors should never be opened. If you dare, turn the page and let’s open that door . . .