Chapter 1

General principles of English construction law

This chapter:

- examines what law is and where it is found

- considers why it is important for an architect to know the law

- describes how law develops and why

- explores why the language we use is so important.

1.1 What do we mean by ‘law’?

Why do we have laws at all? It seems like this should be a simple question, but finding the answer is a vital stepping stone on the way to understanding why it is important for a professional, such as an architect, to know the law.

Laws are sets of rules intended to regulate human behaviour. A degree of order is a necessity in any society, if that society is to be able to sustain itself over a period of time. A ‘society’, an abstract concept, has no separate will or desire to sustain itself. A society is no more than the individual people that make up that society.

The imposition of law is one way of creating order and exerting socia control. If the majority of the people that have the power in a society to impose and enforce laws recognise a benefit in the continued existence of the society, then laws will be created with the aim of sustaining it. If the remainder of the society similarly recognises a benefit in the imposition of those laws, or has no power to object, they will acquiesce in the imposition of those laws.

In a sophisticated, developed society, laws will develop or be created to govern all aspects of human behaviour and interaction, ranging from basic norms of personal behaviour to the rules which govern complex commercial transactions. The law of England and Wales, with which this book is concerned, is a highly developed, multifaceted system Construction law is one aspect of this larger system.

The idea of construction law as a distinct topic, worthy of study in its own right, is a relatively recent one.

- The Building Law Reports, widely recognised as the leading authoritative law reports for construction-related disputes, first appeared in 1976 (the word ‘Building’ on the reports’ title page was originally represented in a variation of the Moore ‘Computer’ font, clearly marking them as a product of the late 1970s).

- The Society of Construction Law was founded in the UK in 1983.

- The Construction Law Journal was first published in 1990.

- The Technology and Construction Court acquired its current name on 9 October 1998, as a rebranding of the Official Referees’ Court.

The term ‘construction law’ is most helpfully understood as referring not to a separate entity, but rather to a broad range of general legal topics (such as contract law, tort and the supply of goods and services) specifically applied to the vast range of activities undertaken by the construction industry.

The place of construction law in the construction industry is emphasised by the way in which the development, and promotion of the understanding of, construction law has been a collaborative process, involving the interaction of construction professionals as well as lawyers. This continued interaction is vital; without the input of construction professionals through bodies such as the Society of Construction Law, construction law would be less responsive, less relevant. Construction law both governs and serves the industry.

1.2 Why legal knowledge is valuable to architects

For the architect, construction law sets the framework within which the practice of their core skills is to be carried out. Whether developing the design, securing consents and approvals, or managing the construction phase, all aspects of the architect’s work require a degree of knowledge of the legal context, beginning with the decision about whether or not to tender for a project, all the way through to RIBA Stage 7, post-practical completion, and managing the risk of ongoing liability in the years after the project has finished.

European procurement law – even in a post-Brexit landscape – may be relevant when considering what rules must be complied with when tendering for the job. The architect will require knowledge of planning law, the law relating to party walls and the Building Regulations when applying for the relevant permissions and approvals. Knowledge of health and safety legislation will be vital for an architect in preparing their designs and administering the building contract. In their contract administration role, the architect will also need a general knowledge of the law relating to the main provisions of the major standard form construction contracts. Knowledge of the law relating to intellectual property will allow the architect to better protect their rights under any appointment with their client. What insurance is the architect obliged by law to carry? What, in law, does the wording of an insurance policy mean for the architect in practice? Will the architect be required to enter into collateral warranties with third parties or grant third party rights? Might there also potentially be liabilities in negligence to third parties?

1.2.1 What standard of legal knowledge is required of the architect?

Underlying all of this is the architect’s relationship with their client. It is important for the architect to know about their own potential rights and obligations in contract law and the law of tort. What do the words in the architect’s professional appointment require them to do? What professional standard must be achieved? If there is a dispute, what are the rules for resolving it?

An architect is not expected to be a lawyer. However, according to the 1978 case of BL Holdings v Wood (at page 70 of the judgment), if they are to carry out their work properly the architect must have enough knowledge of the relevant principles of law to ‘protect their client from damage and loss’. In the Wood case the architect was found by the court to have failed to exercise reasonable skill and care in advising their client on the need for a particular planning permit, because the wording of the relevant Act was enough to make it plain to any competent architect engaged in planning work that an additional permit would be required to make the planning application effective.

The architect’s duty to advise in relation to legal aspects extends to knowing their own limitations; if a legal question arises which is beyond the scope of the architect’s knowledge, they are expected to be able to recognise that specialist advice is required. The architect should refuse to incur additional expense on their client’s behalf until the client has obtained legal advice and made an informed decision.

An awareness of the boundaries of the architect’s expertise is increasingly important. The scope of an architect’s responsibility seems to be ever expanding, paradoxically just as the scope of an architect’s authority is contracting – particularly in the area of contract administration, where shifting professional boundaries have meant that quantity surveyors, project managers and others may all have a say. Architects seem regularly to be approached by clients seeking informal advice in relation to contractor claims, looking for an opinion on the chances for success or, in extreme cases, expecting the architect to in effect run an adjudication. It can be tempting for the architect to offer advice in response to a client’s request, even if the architect knows it is at or beyond the limits of their expertise.

The desire to assist the client in areas outside the scope of the architect’s expertise may be entirely understandable, but it represents a very serious risk.

Professionals holding themselves out as competent to provide particular advice have an obligation to achieve a certain standard of care when giving it. A failure to attain the required standard may leave the architect open to a claim.

1.3 Where does law come from?

1.3.1 Common law – ‘case law’

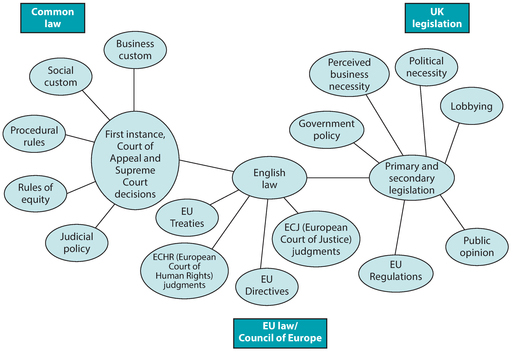

English law, of which construction law is one aspect, is made up of rules from a number of different sources (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Sources of law

There are different legal systems even within the UK. English law subsists in England and Wales. The law of Northern Ireland is subtly different; some legislation applicable to the rest of the country does not apply there, while other statutes apply only to that part of the UK. The court system is also separate. Scotland also has its own courts, but the legal system as a whole is markedly different from that in England and Wales; it is based on a separate legal tradition. Scotland has a ‘civil law’ – a code-based system dating back to the time before the Acts of Union united Scotland and England in 1707.

English law is fundamentally a ‘common law’ system. Originally this simply meant it was the law that applied to (was ‘common’ to) all people in all parts of the country; a uniform set of rules, applied to all and enforced by the King’s courts. There was no single defining moment when this system was adopted, but rather a gradual development and shaping of the law to suit the needs of the developing state.

Case law – how it works

The English system does not originate from any written collection of laws. It is based on the ‘precedent’ of decisions previously made by judges in individual cases. When deciding on the facts presented before them, judges will either follow the existing law, adapt the existing law or, more rarely, create new law.

For example, in the 1957 case of Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee the court established the standard test for what amounts to ‘reasonable skill and care’; if a professional, such as an architect, has acted in a way that a responsible body of their fellow professionals would have acted, then they have used reasonable skill and care and have not been negligent. After the Bolam case, this is now the test used by any court when considering cases where professional negligence is claimed. The facts of the Bolam case involved a claim for negligence being made against a hospital management committee following the use by one of its doctors of electro-convulsive therapy. Although the facts related to a member of one particular profession, a doctor, the court was able to use the individual facts of the case brought before it in order to decide on a legal principle of general application – how should the standard of care to be expected from any professional be assessed? The judge in the Bolam case established a principle of law that still applies to all professionals (not just surgeons) 60 years on.

There is no written set of guiding principles setting out the basis on which those judges should make their decisions. As a result, the system is extremely flexible and able to react, without governmental prompting, to the changing needs of society over time. One drawback of the common law system is that, being based on decisions of judges in individua cases, legal development cannot take place until a suitable case arises. In practice, important issues do tend to generate ‘test cases’ and, where a glaring problem with the law needs to be corrected, it is open to Parliament in its legislative capacity to create a statute to change the law, as discussed further below. It is then for the judges to interpret the statute as and when required by the cases which come before them.

The common law system spread across the world on the back of the expansion of the English-speaking world, colonisation and empire. Common law principles hold sway in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, along with the Irish Republic, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, India, Pakistan, South Africa and a number of other countries.

In contrast, the system of law used in most countries throughout the world is based on the written civil codes of those countries. This system, ‘civil law’, relies on judges to interpret the written code and apply it to individual cases. The resulting interpretations are not binding on future courts. Judges in civil law countries do not make law through precedent. Civil law is prevalent in continental Europe as well as in Scotland, much of Africa, Asia, the Middle East and South America.

1.3.2 The courts apply the law of ‘equity’ too

Although the common law system we know now is remarkably adaptable and flexible, it became apparent over time that the common law was, in some instances, unable to keep up with changes in the way people conducted their business and some decisions were perceived as unfair. Over time, a parallel way of bringing claims developed; petitions were heard in the Court of Chancery, originally the court presided over by the Lord Chancellor. In contrast to the common law judges, the Chancellor and his judges were not constricted by the development of procedural rules, and therefore greater flexibility and creativity were possible in terms of available remedies.

Since 1873, all courts have applied the rules of both common law and equity. In the event of a conflict, the rules of equity are to apply. Is the distinction between ‘law’ and ‘equity’ still relevant? The subtle differences between rules derived from common law and those derived from equity can still be important for the parties to a case. The ability to claim an equitable remedy (such as compelling a party to take a particular course of action through an injunction or an order for specific performance of a contract) is not strictly speaking a ‘right’, but is still considered to be subject to the discretion of the court. Whether an equitable remedy can be granted depends on the justice of the case, the behaviour of the parties and whether an alternative common law remedy would be adequate; it depends on whether in all the circumstances an equitable remedy would best do justice between the parties.

1.3.3 The central role of the courts in making and applying law

Because the development of common law is dependent on the reasons given by judges for deciding individual cases, it is important that their judgments are written down. The common law is found in the reports of judgments. Not all cases make new law, but it is essential that those which do are recorded in authoritative law reports – for example the Building Law Reports, which cover construction cases – available to all courts and lawyers. Perhaps surprisingly there is no official free law-reporting service, but reports of many cases are now available on the internet. Most civil appeal cases and many High Court decisions are available for free on the website of the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII):

- www.bailii.org

The civil court system in England and Wales features two levels of ‘first instance’ courts (Figure 2). The county courts deal with relatively small-scale litigation, often claims for sums of money under a threshold of £10,000. These courts may be relevant to an architect, for example in the recovery of fees. Extensive guidance on making and defending small claims is available on the website of Her Majesty’s Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS). Some claims can even be made online; details of the procedure are again available on the HMCTS pages of the Ministry of Justice website:

Figure 2 Civil court hierarchy in England and Wales

- www.justice.gov.uk

Even if the amounts involved are small, certain types of action are considered too important for the county courts (this guidance comes from Practice Direction [1991] 3 All ER 722 as amended). Professional negligence actions are among those types of action that are generally only suitable for the High Court. The High Court is the ‘senior’ court of first instance, hearing more complex cases with no financial limit. For administrative purposes, the High Court is subdivided into three divisions: the Queen’s Bench Division, which is the main common law court; the Family Division; and the Court of Chancery. Cases involving architects will usually be heard in the Technology and Construction Court (TCC), one of the specialist courts of the Queen’s Bench Division. The HMCTS website contains numerous guidance leaflets relevant to High Court claims, as well as county court actions and appeals, and an extensive range of court forms, available to download for free.

If a party is not satisfied with the outcome of a case, there may be grounds for appeal to a higher court. Strict time limits generally apply and leave to appeal will be required, either from the trial judge or the Court of Appeal itself. Appeals against the outcome of a hearing in the county court or the High Court are mostly dealt with by the Court of Appeal Civil Division. Due to the likely time commitment and costs involved the appeal process is not something to be considered lightly.

The ultimate domestic appellate court is the Supreme Court, known until October 2009 as the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. The Supreme Court deals almost exclusively with appeals that raise important issues of law. Leave to appeal will be required from the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court, and is rarely given. The Court of Appeal is, for most cases that are appealed, the last word on that particular case; it hears several thousand appeals each year, of which only around one hundred go on to be heard by the Supreme Court.

1.3.4 Courts are bound by precedent

As discussed above, the basis for judicial decision-making, and consequently the basis on which lawyers advise their clients and make their arguments before judges, is not a written code, but rather the application of an unwritten principle that earlier decisions from authoritative courts should not be departed from. A decision of a judge in a particular case is a ‘precedent’. Subsequent judges are said to ‘apply’ the decision when they ‘follow’ it in cases that come before them. Apart from the Supreme Court, the courts at each level in the English system are bound to follow the previous decisions of courts above them in the hierarchy, and appellate courts are bound by their own previous decisions.

Judges everywhere will tend to decide like cases alike, but the application of this principle in English law is uniquely strict, with judges in all but the highest appellate court having a positive obligation to follow previous decisions unless a case can be ‘distinguished’ from those decisions on its facts. The judge’s obligation is to do more than simply take those previous decisions into account; sometimes it is apparent from reading a judgment that a judge disagrees with a principle of law contained in a binding precedent, but must nevertheless follow it if they cannot find a way to distinguish the current case from it.

There are rules within this rule of binding precedent. Subsequent judges are not bound by all of what has been said in a judgment, only by the essence of the reason for deciding the case in the way it was decided, known to lawyers who love jargon as the ratio decidendi. There is no absolute formula for identifying the ratio. One rule of thumb suggests that the ratio for a decision is that part of the legal reasoning which, if it had been reasoned differently, would have led to a different decision in the case. But cases rarely turn on just one point; sometimes the final judgment is based on layers of reasoning, and the absence of any one element could have led to a different outcome. As a result the ratio of a judgment can often be open to argument. Sometimes it is more clear-cut; for example, the ‘ratio’ of the Bolam judgment described above in section 1.3.1 is: if a professional has acted in a way that a responsible body of their fellow professionals would have acted, then they have used reasonable skill and care.

For the system to work, judges employ reasoning by analogy in order to decide when a case is sufficiently similar to a previous case and therefore when a precedent applies. The facts of the current case do not have to be exactly the same as those of the precedent. For example, the Bolam case concerned an allegation of negligence against a medical professional but the rule established in that case applies equally to any professionals, including architects.

Although the rule of precedent is considered to be far more strictly applied in English law than in other jurisdictions, there is considerable scope for courts to exercise their own judgment. It is up to a court to decide not only whether the facts of a case fall within the scope of a previously decided case, but also what the principle of law contained in the previous decision actually is. The legal reasoning in a judgment has to be credible if the judgment is to survive, but the ratio, reasoning by analogy, and applying or following a decision can all be seen as control mechanisms available to a judge to better justify adhering to a precedent or departing from it in order to do justice to the facts of the case before them.

1.3.5 Law may be created by Parliament too – ‘legislation’

Legislation comprises the written law created by or under the authority of Parliament, which has supreme authority to make and unmake laws. The term ‘legislation’ includes Acts of the UK Parliament itself (primary legislation) as well as the various Statutory Instruments, orders, regulations and by-laws known collectively as ‘secondary legislation’. These rules are made not by Parliament but, for example, by the government of the day, government departments or local authorities, and derive their authority from Parliament.

Acts of Parliament take precedence over all other domestic sources of law. If an Act of Parliament contradicts a common law rule it is presumed that this was Parliament’s deliberate intention and a court will be absolutely bound to comply with the statute.

It is important that architects keep up to date with important changes or proposed changes in legislation, primary and secondary, in areas relevant to their professional practice. Important examples include the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 and the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009, the two ‘Construction Acts’. Even if legislation is relatively new, it is not acceptable for an architect to fail to keep abreast of relevant legislative changes Another obvious example would be updates to the Building Regulations.

For the most part, a full copy of all legislation, both Acts of Parliament and secondary legislation, is available free of charge on the internet:

- www.legislation.gov.uk – provides links to all published Acts o Parliament from 1988 onwards, and many other major Acts, dating back as far as 1267, along with links to all Statutory Instruments from 1987 onwards

- www.parliament.uk – makes Bills currently before the UK Parliament freely available.

The UK Parliament website makes it possible to track the progress of relevant proposed legislation during its course through the legislative process. If an architect is in any doubt about the likely practical effect of a particular provision in an Act of Parliament, Statutory Instrument or any other piece of legislation, it is recommended that they seek legal advice.

1.3.6 EU law

Since the UK was allowed to join the European Economic Community in 1973, that institution (now the European Union, or EU) has assumed a powerful role in the creation of laws that directly affect this country. Following the vote in favour of Brexit, this may be about to change – but perhaps in ways that are more subtle than many might expect. Though the full effects of Brexit may not become clear for many years, it must remain likely that EU law will continue to exert an influence over the commercial and regulatory landscape within the UK.

EU law consists of several layers of legislation, some immediately directly effective in the member countries of the EU, and others not. Most new legislation from the EU is in the form of either a ‘Regulation’ or a ‘Directive’. For now, regulations are given force directly by virtue of the Act of Parliament under which the UK originally acceded to the European Economic Community. Directives, as the name suggests, direct individual states to achieve a particular result, but leave it up to those member states to decide on the best way to do so. In this country, that will typically involve a UK Act of Parliament to implement the Directive.

As well as the legislative bodies within the EU member states, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) exists to interpret and implement EU law and is effectively – again, for the time being – a further rung of appeal above the UK’s own Supreme Court. In the field of EU law, ECJ judgments over-rule those of the national courts of EU member states.

Within the Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, including the UK, the European Court of Human Rights deals with cases relating to the European Convention on Human Rights, which has been directly applicable in the UK since the Human Rights Act 1998.

EU law takes precedence over any domestic law in the event of a direct conflict. Its influence has been pervasive, covering many areas of law relevant to architects’ practices and professional work: the recognition of professional qualifications, the law relating to procurement of works by public bodies, competition law, consumer protection and, particularly, health and safety.

1.4 Law is not static – it evolves

Laws, and the functions a society requires its laws to perform, will change over time as the society develops and the roles and responsibilities of the members of that society are reinterpreted. Issues that once seemed important enough to warrant making a new law may in time become irrelevant, and the law in that area will become obsolete. Laws can be created to meet a perceived need, or adapted, or repealed. The nature of law is surprisingly fluid and continually evolving. Moral, political, economic and other factors all have their influence.

The ‘commercial law’ of England and Wales, as broadly understood includes construction law to the extent that it governs the actions and interactions of commercial parties. The commercial law has reached its current state following slow, often painful, evolution over many hundreds of years.

Other factors have certainly played a part, but the underlying drive behind the development of all commercial law, including construction law, is economic; when parties such as architects make a contract, the law is there to give them the confidence that the deal they have made will be enforced in a predictable way. No commercial contract is risk free, but parties can manage the risks if they know that the law will implement the contract terms in the way they expect. This predictability is also good for society as a whole; removing the need for commercial parties to take unnecessary legal advice makes business more efficient and profitable, with positive consequences for the wider community through jobs and tax income.

The development of a law suitable for business users can be summarised as the result of three processes: ‘facilitation’, ‘integration’ and ‘regulation’. For a more detailed discussion, in the contexts of company law and the sale of goods, see Lord Irvine of Lairg’s paper The Law: An Engine for Trade (2001 MLR 333).

The law relating to commercial contracts – and which governs architects’ professional appointments with their clients, building contracts, collateral warranties and all the types of legal agreement that architects may expect to have to deal with – facilitates trade, creating business confidence through the (generally) predictable enforcement of rules that have developed with business interests in mind. This can be seen in the way in which contract law fills in the gaps in private agreements by implying terms that the parties did not expressly include.

1.4.1 The law develops to facilitate business

Contract law allows parties the freedom to make their own business arrangements, tailored to suit their individual purposes. Some agreements may give the appearance of being a complete contract. It is rare, though, for a contract to contain every provision necessary to make clear what deal has been done, and the law will imply additional terms in three situations:

- when the implied term is necessary to make sense of the contract

- when the term reflects the ‘usual’ approach, and has not been excluded, or

- when statute requires the implication of a term.

Implied terms provide a safety net for parties to business contracts. If it can be shown that, even though all the components of a complete contract are in place, the contract as drafted does not make business sense, then the law will imply terms if they are necessary to make the contract reflect what it is assumed the parties must have intended.

1.4.2 The law develops by integrating existing patterns of behaviour

If there are ‘usual’ terms that were not expressly set out in the contract, but which the parties would, if asked, have acknowledged to be part of their bargain, again the law will imply them, so long as the contract contains no express term to the contrary. An example is the implied duty of the employer under a building contract to co-operate with the contractor to allow the contractor, all other things being equal, to carry out and complete the works. This implied term has an impact on the role of the architect; the employer will be liable for a breach of the implied term of co-operation if the architect fails to do those things required of them to enable the contractor to carry out their work. The law has in this way assumed certain rules that grew up through repeated use by and expectations of the business community.

1.4.3 The law develops to regulate behaviour that is bad for business

When it has been necessary for Parliament to regulate the construction industry through legislation, the law implements the new rules by implying additional terms into contracts to give them effect. Examples include the 1996 and 2009 Construction Acts.

If a construction contract does not contain Act-compliant provisions relating to payment and the right to adjudicate, the terms of the Scheme for Construction Contracts must apply to make the contract compliant with the Construction Acts. The current relevant provision, contained in the 1996 Construction Act, section 114(4), states:

The Construction Acts typify business-led legal development. There was extensive lobbying of Parliament in the years leading up to the creation of the 1996 Construction Act, and similar pressure leading up to the 2009 Act. The 1996 Act was focused on improving cash flow within the construction industry by requiring fairer payment mechanisms in construction contracts, and by creating a statutory right to refer disputes to adjudication, a much quicker and cheaper alternative to litigation. The 2009 Act consolidated the law in relation to these two key areas.

It is understandable that business people are likely to operate to maximise their own profits, even though this may prejudice society as a whole.

Prior to the 1996 Construction Act, payment practices within the construction industry were making business life too risky for the parties lower down the payment chain – the specialist design consultants and subcontractors that are a vital component of the industry.

Bullying clients and contractors were too often ensuring that the consultants and other specialists would take the risk that payment would not be forthcoming.

The inevitable result of the increasing risk of non-payment was that the pool of specialist talent diminished as people left the industry. The result was that prices went up. In addition, there was the problem of ‘externalities’, detrimental effects (other than the increase in prices) suffered by society as a whole. These effects included the discouragement of clients from instigating projects, a reduction of choice in terms of tenderers for projects and a decline in quality and innovation in a less competitive market. When Parliament created the 1996 Construction Act it did not do so out of altruism, but because better protecting the position of specialist designers and subcontractors was a business necessity.

The facilitation and regulation of business practice, and the integration of business ideas into the law, demonstrate how, throughout its development, the law has been driven by, and has acted as a driver for, industry. As the creation of the 2009 Construction Act shows, the dialogue between law and business continues, as it must. The relationship is one of mutual dependency, with Parliament and the judiciary striking a balance between the self-interest of the business community and the interests of the public as a whole, reconciling, in Lord Irvine’s phrase, ‘laissez-faire and excessive regulation’.

The law of England and Wales as it affects the conduct of architects should be seen in this context. The existence of a legal framework within which architects must conduct their business encourages the business of the construction industry and is beneficial to society as a whole.

1.5 Language and law

Language is a problem. One popular misconception about the law and one unfortunately propagated by some lawyers and politicians, is that the law can provide certainty through definition. This is not, and cannot, be the case, because of the unavoidable uncertainty associated with the use of language. All words have a core of meaning, but a word used in particular to stand for an abstract concept (for example, ‘love’ or ‘reasonable’) is always likely to have a ‘penumbra’ of uncertainty – possible aspects of the thing for which the word stands which some people may understand to be within the scope of the word’s meaning, but others may not. In difficult cases, it is perfectly possible for two rational people to have entirely different views.

This is an issue of practical importance for architects and their lawyers An architect should always have a written contract, their ‘professional appointment’, with the client. The appointment should set out as clearly as possible:

- the terms of the agreement between architect and client

- what services will be provided

- when fee payments will be made.

The architect may need to interpret their appointment to understand precisely the extent of their services. In the event of a dispute, the architect’s lawyer will interpret the appointment, and any relevan background legislation or case law, to see if their client has a viable case. If a case comes before an adjudicator or a judge, they in turn will have to interpret the relevant documents to decide where justice lies. At each stage, someone is making a judgment about the meaning of words.

An example popular with legal theorists focuses on the word ‘vehicle’ which was used but not defined in the 1930 Road Traffic Act and others since. The 1930 Act made it an offence to use a trailer (which the Act defined as a ‘vehicle drawn by a motor vehicle’) without pneumatic tyres on a road. In the 1951 case of Garner v Burr, the court had to decide whether Mr Burr, who took to the road driving a tractor towing a poultry shed fitted with iron wheels, was guilty of an offence. Was a poultry shed a vehicle? This case demonstrates one very important reason why legal language is so often open to different interpretations.

Legal meaning depends on the context in which the words are used

The court in Mr Burr’s case said that the natural meaning of the word ‘vehicle’, which would not ordinarily bear an interpretation that included a chicken coop, had to give way to a wider meaning that was necessary to give effect to Parliament’s clear intention in creating this part of the Act – the protection of tarmac road surfaces (Figure 3).

Inaccurate use of language can lead to disputes

Many disputes begin with the imperfect use of language. It is in the interests of the law and its users that words used for legal purposes, in contracts and statutes, should be as certain as possible, with the narrowest penumbra of uncertainty. But what does the impossibility of ‘certainty’ mean for an architect, practically? Is it even necessarily a bad thing? Legal certainty is important for business confidence. Commercial parties need to be able to properly assess the risks they are taking on when they make a contract; this cannot be done if it is not possible to predict how a court will interpret the words used in the contract, or the words of the relevant background legislation.

Figure 3 The ‘penumbra’ of meaning: ‘vehicle’

Some party or other will have lost out as a result of every development over the course of English legal history, from the very beginning; from the party who could predict how their local lord would deal with an issue in his feudal court, only to find that their case met with a different interpretation when heard before the King’s travelling justices. But parties have in the past also suffered injustice due to the unyielding rigidity of procedural rules, which created an unwelcome sort of certainty. Inflexibility in procedural law and an inability of the substantive law to adapt to changing business needs could each lead to unfairness. How is the balance to be struck?

Sometimes a legal interpretation of language can, on the face of it, look illogical. In the Court of Appeal case Tyco Fire & Integrated Solutions (UK) Ltd v Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Ltd, which concerned a building contract insurance issue, the definition of the term ‘the Contractor’ became crucial. The defendant, Tyco, was named in the building contract as the Contractor, with a capital ‘C’. The employer had been obliged to maintain joint names insurance to cover various parties ‘including, but not limited to, contractors’. The court held that Tyco, the capital ‘C’ Contractor, was outside the class of parties defined as including ‘contractors’ with a small ‘c’. At first glance this is a difficult distinction to understand and seems to be at odds with the logical interpretation that the main contractor, however described, should still be within the wider class of ‘contractors’ working on the project. But the court stretched the meaning of the words and favoured the less obvious interpretation because, on the facts of the case, it was the correct interpretation in order to do justice between the parties.

The absence of certainty in language allows courts room for manoeuvre to do justice between parties in hard cases, where an obvious interpretation can be made to give way to another, reasonable but less obvious, interpretation. The facilitation of justice in such cases, and the development of the law to meet changing needs, are the benefits of allowing judges to exercise their discretion when interpreting legal words. The price parties must pay is accepting the risk that the wording of a contract or statute may not mean what they had assumed it meant.

In his articles Language and the Law (1945/1946 LQR 61/62) Glanville Williams said:

This must be true, but it should not stop commercial parties from aiming to be as accurate as possible in the language they use to express the contracts they make. Certainty may be unattainable, and failure inevitable, but parties have to aim to ‘fail’ as well as they can.

The most important context for the architect is the wording of their own professional appointment. Even if we accept that the nature of language means there is always likely to be room for argument about the meaning of any particular set of words, it is still a fact that some contracts are better drafted than others. Some forms of words invite confusion; others are only likely to be the subject of dispute if the stakes are high enough to warrant innovative arguments by expensive lawyers. It is always worth recording the agreed contract terms in writing.

Chapter summary

- Architects need to know about the law because there is a legal context for all of the services an architect may provide.

- Law comes from a number of different sources, and an architect should know where to look to find the law.

- The law is subject to change, and architects have to keep themselves up to date.

- An architect does not have to be a lawyer, but needs to know enough to be able to advise when a client should seek specialist legal advice.