Key 2

Make the Most of Learning

Those who want to experiment without possessing some knowledge are like navigators who set sail without a rudder or a compass and who are never sure where they are going.

—Leonardo da Vinci

It was 1945, World War II was over, and the United States was adjusting to the end of rationing. Beef and butter could again be purchased in any quantities. The wartime rules allowing the manufacture of only black, white, and brown clothing were lifted, and clothes could now be purchased in many colors.

On Front Street, in the heart of the cotton town Newport, Arkansas, John Dunham owned a store with annual sales of $150,000. The Ben Franklin Store across the street was a loser, with annual sales of $70,000 and a high lease of 5 percent of sales. When he learned that a returning soldier had bought the store, he felt pity for him. So when Dunham found the young man roaming his store, checking on his prices and displays, he was glad to answer the man’s seemingly endless questions.

At first, Dunham was amused by the young man’s wild promotions: a popcorn machine out on the sidewalk, a Ding-Dong ice cream machine, and a sale of ladies’ panties at four for a dollar. But Dunham’s amusement was short-lived. In a few years, the soldier’s sales exceeded his. To counter the threat, Dunham decided to lease the property next to his store and expand. But he made a mistake by discussing his plan with friends. When he drove to Hot Springs to sign the lease, he got the shock of his life. The lease had already been signed by the friendly returned soldier, Sam Walton (figure 2-1).

Lifelong Learning

Throughout his life, Walton studied the expertise of the competition. Once, when he heard that a retail store in Minnesota had placed all its checkout registers at the front of the store instead of in each department, he traveled more than 500 miles on a bus to learn how it worked. When he introduced the practice in his stores, he found that it not only saved shopper’s time; sales actually increased. His thirst for knowledge never ceased.

Years later, after Walton had already built his sprawling empire, he traveled to South Africa to learn the expertise of a small retailer who was doing exceptionally well. For 12 hours a day, as a guest of the small retailer, he visited stores, examined floor designs, checked inventories, questioned customers, and talked with vendors— taking notes all the while. He believed that anyone who was successful, even in a small way, had expertise worth learning. He also had the humility to ask others to teach him. In 2001, Wal-Mart became the largest corporation on Earth, with more than $200 billion in sales and 1 million employees.

To help you understand how the great achievers learned faster and better than others, this book often uses the word “expertise,” meaning extensive knowledge and ability gained through study and experience. Walton and other great achievers found the answer to three important questions about expertise:

- Why is expertise so valuable?

- Which expertise is the most valuable?

- What are the most powerful ways to learn expertise?

Why Is Expertise So Valuable?

Popular books don’t stress the importance of expertise in achieving success, but researchers agree that it’s the most critical factor. Pablo Picasso referred to its value in describing an incident that took place on a sidewalk in Paris. He was sketching when a woman spotted him and asked to have her portrait done. He agreed. In minutes, she was depicted in an original Picasso. When the woman asked what she owed him, Picasso said 5,000 francs. Surprised, she protested that it had only taken three minutes. “No,” Picasso told her. “It took me all my life.” Picasso is quoted by Harry Beckwith, Selling the Invisible (New York: Warner Books, 1997).

Frederick Douglass also knew the value of expertise. In 1827, as an American slave, he was sent to live with a white plantation family. For the first time in his life, he walked on carpets instead of dirt floors and had shoes and a hat to keep him warm (figure 2-2). He no longer shared corn mush with other children from a trough on the floor. He was intrigued that the family members read books, and he begged the lady of the house to teach him how to read. One day, a few weeks into the lessons, as she was praising the boy’s progress, her husband flew into a rage, telling her that she was breaking the law; if she taught the boy to read, he’d be unfit to be a slave. He said the boy should know only the will of his master.

Overhearing this, Douglass was hurt. But he also was impressed. If reading was that valuable, he wanted to read. From that day on, he hoarded scraps of printed paper as if they were gold. While he worked long hours in a factory, he studied newspapers that he nailed up at reading height. At the age of 13 years, he purchased his first book, The Columbian Orator, with money he earned by shining shoes. He believed learning was an opportunity rather than a chore.

Douglass escaped from slavery and, at great risk, he toured the United States, speaking for emancipation. He wrote a best-selling book about life as a slave and founded the first black-owned newspaper. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln sought his counsel on the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1871, he promoted the passage of constitutional amendments banning slavery, making citizens of all people born in the United States, and outlawing racial discrimination in voting.

Expertise set Douglass free, and he set others free. The sidebar highlights the opinions of some major researchers and practitioners on the importance of expertise. For more on Douglass, see Joel A. Rogers, World’s Great Men of Color (New York: Touchstone, 1947).

The Importance of Expertise

Howard Gardner, the creativity guru from Harvard, analyzed the talents, personalities, and work habits of Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Mohandas Gandhi, Martha Graham, T. S. Eliot, Igor Stravinski, and Pablo Picasso; see Howard Gardner, Creating Minds (New York: Basic Books, 1993). In all cases, their creative breakthroughs took place after 10 years of study and the acquiring of experience—time in which they devoted almost their whole beings to their chosen fields.

Teresa Amabile, a leading creativity researcher, says, “Being creative is like making a stew. The essential ingredient, like the vegetables and meat in the stew, is expertise in a specific area. No one is going to do anything creative in nuclear physics unless that person knows something, and probably a great deal, about nuclear physics.” She is quoted in The Creative Spirit, by Daniel Goleman, Paul Kaufman, and Michael Ray (New York: Penguin Books, 1992).

The prolific inventor Jacob Rabinow once said, “If you’re a musician, you should know a lot about music. . . . If you were born on a deserted island and never heard music, you’re not likely to be a Beethoven; . . . you may imitate birds, but you’re not going to write the Fifth Symphony.” He is quoted in his book Inventing for Fun and Profit (San Francisco: San Francisco Press, 1990).

Expertise Versus Heredity and Circumstance

Some people downplay the importance of expertise. They say that leaders are born to lead or have certain personality traits that make them good leaders. Some say that leaders become great because they’re in great organizations or because of the situations in which they are leading. They use Winston Churchill as an example of a leader who became great because World War II occurred during his term of leadership.

The fact is that Churchill had been an influential military and government leader for 35 years before World War II. He became a national hero in 1899 for his daring leadership and his escape from imprisonment in South Africa. He was elected to Parliament for 40 years in a row, beginning in 1924. He was an expert on history and saw the future as few have. He warned the world about Hitler many years before Hitler’s evil was apparent to others. In the late 1930s, Churchill vigorously and publicly opposed those who appeased Hitler by allowing him to take portions of Poland and Czechoslovakia.

As World War II broke out in Europe, Churchill was asked to serve as leader of the British Admiralty. He devoted himself to building up the navy and developing antisubmarine warfare. When Arthur Neville Chamberlain resigned, King George asked Churchill to become prime minister and to lead the British war effort. By this time, Churchill was an expert on government, the military, and leadership. His expertise proved crucial to winning the war.

The “great achievers” whose lives are highlighted here are all giants. How do we know that the same 10 keys are important to people who aren’t giants—who make smaller but still valuable contributions? Do these keys really apply to everyone?

To answer this question, we researched many lesser-known achievers. But we held to a rule. To be sure that the keys stand the test of time—that they will be valid 100 years from now—we studied only those who had sustained success for at least 10 years.

Expertise and Opportunity

Although less well known, Vito Pascucci qualifies as an achiever. In high school, he learned to repair musical instruments. When he went into the army during World War II, the great bandleader Glenn Miller heard of his repair skills and had him assigned to his band. After Paris was liberated toward the end of the war, his job was to drive a truck with all the band’s instruments to Paris. Miller flew. Pascucci and Miller planned to visit musical instrument manufacturers while they were in Paris, so they could open music stores across the United States after the war. It was Pascucci’s dream of a lifetime (figure 2-3).

When Pascucci reached Paris, he was devastated by the news that Miller’s plane was missing—lost at sea. The dream was over.

When the shock wore off, Pascucci visited instrument companies himself. During one visit to a factory, his life took another turn. His tour guide told him that the company wanted to sell instruments in the United States, but instruments lost their performance during sea shipment. Pascucci told the guide to give the wooden parts time to stabilize in the new atmosphere in the United States. If they were then reassembled, adjusted, and tested, he was sure they could be restored to factory specifications. Impressed, the guide invited him home for dinner. The guide turned out to be the instrument manufacturer’s son, Leon Leblanc.

After the war, Pascucci set up a Leblanc branch office in the United States. By day, he restored instruments shipped from France to factory condition. By night, he wrote to retailers and distributors. Sales grew so fast that the French factory couldn’t keep up. So it had Pascucci build a plant in the United States. Years later, he bought a controlling interest in the entire company. The Leblanc firm has won every award for musical instruments and today is a world symbol of performance and quality.

Pascucci’s success again shows the importance of expertise in finding and seizing opportunities. He found the opportunity with Glen Miller because he was an expert in his work. Misfortune took that opportunity away. But the Leblancs offered Pascucci another great opportunity because he had the expertise. The great achievers like him have considered expertise so important that they’ve devoted themselves to becoming “expert insiders.”

Becoming an Expert Insider

Many people say that insiders are too biased to create new ideas; that new ideas always come from outsiders. We have found that this isn’t true. They called Einstein an outsider because he didn’t work with any of the great physicists of his time before he developed his Special Theory of Relativity. But he graduated from the Swiss Polytechnic and was more of an expert in his field than any person alive when he made his breakthrough.

Edison was considered an outsider because he finished only the fourth grade and wasn’t part of the existing lighting market. But before his team invented electric lighting, he and his team had extensively studied what other pioneers in electric lighting had done, and they knew they could invent a light that would be far superior to anything that had been invented. In other words, they knew more than anyone else.

Bill Gates was considered an outsider. But he and Paul Allen knew more about personal computer software than anyone else in the world at the time.

In other words, Einstein, Edison, and Gates were expert insiders.

Power Insiders

A second type of insider, the “power insider,” has the power and control of the resources in a field but seldom comes up with the big innovations—according to the research that Burton Klein did on 20th-century innovations; see his Dynamic Economics (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977).

Research done by John Jewkes and his colleagues also revealed that expert insiders who were “outside” their industries came up with almost all the big innovations in the 18th and 19th centuries; see The Sources of Invention, by John Jewkes, David Sawers, and Richard Stillerman (London: Macmillan, 1960). In other words, while less successful people around them were waiting to win the life lottery, the great innovators knew that the chances of finding and seizing great opportunities are higher for those who have high expertise in their fields.

The Need to Spend Time Learning

In writing this book, we received much feedback about how most people don’t want to hear about spending a lot of time learning. Many people are looking for drive-through success. People would rather hear that the power and creativity are within them, and they just have to find ways to release and harness them. Although it is true that power and creativity are within us, we have to develop the expertise to tap into them. If someone lacks expertise in a field, he or she has little to release to that field.

Certainly, Einstein, Gates, and Abbott Laboratories spent a great deal of time in preparation. But even small investments in preparation pay off. If Edison had spent a little time studying the market for an electric vote recorder, he wouldn’t have wasted his time and other people’s money on it. He learned the value of a small amount of preparation when he failed. From then on, he spent a lot of his time learning.

The great achievers spent a lot of time learning about their work and their markets. But they also knew that the amount of expertise they needed was greater than they could ever achieve with ordinary learning processes. Although it’s hard to believe the great achievers thought anything was beyond them, they knew they weren’t superhuman. They saw the obstacles and overcame them.

Overcoming the Obstacles to Gaining Expertise

The available expertise of any field is large and growing rapidly. Tens of thousands of books and articles are published each year. Yet people have the same 24 hours a day and no better minds than those who lived in Michelangelo’s time. With ordinary approaches, no one can hope to become an expert insider.

You may argue that people live twice as long, on the average, and have information systems and communication technology that the earlier great achievers didn’t have. But today’s world is more complex and demanding. Examine how much time you spend expanding your expertise in your field. To repeat, the great achievers knew the importance of expertise for success and they knew that the amount of expertise in their fields was greater than they could ever learn. So they “leveraged” their time, brainpower, and resources. Figure 2-4 shows a graphical representation of the total expertise of any field versus the high-leverage expertise and ability to learn. The figure assumes that not all processed expertise will be high leverage—note the lower circle in the diagram.

High-Leverage Focus

The great achievers focused on the expertise that was most valuable in their work or their markets. In other words, they always set themselves up to get the largest rewards for the time and resources they spent. Their thinking was based on the ancient principle of mechanical leverage. The earliest humans discovered how to use mechanical leverage to go beyond their physical limitations. They found that a person easily could lift a one-ton weight with a well-designed lever. Archimedes first put the principle in writing in 200 B.C. To make his point, he said, “Give me a lever and a place to stand and I will move the earth.”

In the same way, the great achievers discovered the mental equivalent of the mechanical lever. They looked for where they could focus the smallest amount of time and resources to produce the maximum gains toward their goals. This took them beyond the limits of the normal human mind and of their personal time and resources.

Which Expertise Is the Most Valuable?

Sam Walton had the ability to identify the expertise that gave him the best chance of success, compared with the time and effort he had to spend acquiring it. After he had multiple stores, he decided that his company needed expertise in computers and that someone else could achieve that better than he could. He attended an IBM class on information technology, with the purpose of hiring a person from the class who could lead that effort, and he did.

We define the most valuable expertise as high-leverage expertise and, fortunately, it’s only a small part of all the expertise in an area of work. But how does a person identify the high-leverage expertise of a particular field? See the sidebar for the example of trout fishing.

Both Leonardo da Vinci and Thomas Jefferson used high-leverage thinking by seeking expertise from masters in their fields. In his book Leonardo (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1992; from which the quotation at the start of the chapter is taken), Roger Whiting quotes memos that da Vinci wrote to himself:

- “Ask a maestro how mortars are positioned on bastions by day and by night.”

- “Get the master of mathematics to show how to square a triangle.”

- “Find a master of hydraulics and get him to show how to repair, and the costs of repair, of a lock, canal, and mill.”

In 1769, Jefferson was elected to the Virginia Assembly. Although he was already a well-educated man, one of his first acts was to order and read 14 books, written by the giants in the field, on the theory and practice of government. For more on Jefferson, see Thomas Jefferson by Willard Sterne Randall (New York: HarperCollins, 1993).

When we asked masters which expertise gave the highest leverage in their fields or markets, they said it was

- the fundamental concepts and principles

- the significant patterns

- the best processes, tools, and technology.

Let’s consider each type of expertise.

Fundamental Concepts and Principles

Although the tools of carpenters have changed, the fundamental concepts and principles of carpentry are the same as they were for the ancient builders of ships and buildings. Even 1,000 years ago, master carpenters knew how to design roof trusses that would support a roof for 1,000 years without sagging.

Yet the key principles of medicine have changed greatly. Doctors no longer believe that draining the blood from a patient will eliminate a disease. But 150 years ago, doctors didn’t sterilize before an operation because they believed that tiny germs couldn’t kill people.

Edison always identified the fundamental concepts and principles he had to learn to invent his newest product, and he either learned them himself or hired an expert insider. Scientists of Edison’s time said that light bulbs would never be used in the home because they used too much current and there was not enough copper in the world to carry the current to millions of homes. So Edison hired Francis Upton, a Princeton physicist, who knew the design principles needed to produce a low-current filament for a light bulb. Edison and Upton came up with a design that used only 1 percent of the original current. The design concepts they developed are still used today to make incandescent light bulbs.

If you want to become expert in trout fishing, you might hire a trout-fishing guide. The guide may teach you to hold a tiny net at the surface of the fast-moving water to find the most frequent insect, because the trout will always bite on the one that’s most plentiful. Trout are high-leverage thinkers. Then the guide will give you an artificial fly that matches the most plentiful insect and teach you to cast upstream of the fast-moving water and to let the fly drift naturally. This is high-leverage expertise that would take a long time to learn on your own. A good book written by an expert may also do the job, minus the feedback from the guide who is there to correct your technique when you snag a bush or lose a biting fish because you didn’t set the hook properly.

Significant Patterns

The architecture researcher Christopher Alexander concludes that patterns are the sources of creative power in individuals who use them; without patterns, they cannot create anything. He says that a person who has a great deal of experience building houses has a rich and complex set of patterns from which to work. If you take those patterns away, the builder can perform only simple tasks. For more on this, see Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

Those who learn the patterns of stock prices or the pattern that a wide receiver runs on a football pass play see a rich world of relationships and designs that others cannot see. The Velcro fastener was inspired by the pattern that allows seed burrs to stick to trousers. The inventor of the pull-top tab for soda and beer cans was inspired by the way a banana peels.

Leonardo da Vinci advised that we take the time each day to study the world around us for its patterns.

Best Processes, Tools, and Technologies

A master carpenter also has a vast storehouse of processes for shaping wood, such as sawing, drilling, routing, and sanding. Once a carpenter visualizes what he wants to construct, he will select and use the best process he knows and the best tools he has for each step in the construction. Most modern companies do not survive unless they adopt the best lean processes, tools, and technologies in their manufacturing areas and computer-aided design technologies in their product-development areas.

Creatively Combining Expertise to Create New Products

Expertise is growing so fast that few people today can become expert insiders in more than one work area at a time. However, many major innovations are the result of creatively combining the expertise of many fields. For instance, to create a light bulb, Edison hired experts in glassblowing, vacuum technology, chemistry, physics, machining, magnetics, model making, and electricity. He managed this team of experts to creatively combine their expertise.

To create computer-animated motion pictures, such as Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, and Monsters Inc., Pixar’s founder, Ed Catmull, brought together expert artists along with experts in computer programming and animation (as related by Gardiner Morse in “Conversation with Ed Catmull,” Harvard Business Review, August 2002). Each person was cross-trained in the tools that Pixar uses and in filmmaking, sculpting, drawing, painting, and improvisation.

Finding the Sources of High-Leverage Expertise

The great masters sought other masters to identify which concepts, principles, patterns, processes, and tools were most valuable in their fields or markets. They read the writings of the masters, attended their lectures, and worked with them. They hired or collaborated with people who had great expertise.

Some people say it’s not what you know but whom you know. Our research says the expression should read “It’s not only what you know but whom you influence.” Many who were in the right place at the right time didn’t see an opportunity because they lacked expertise in their field. Others knew the right people but lacked expertise in influencing others. You need both expertise in your field and expertise in human behavior. Edison had expertise in electromechanical invention and in marketing his inventions through the press. Colonel Sanders had expertise in frying chicken and in influencing people to buy franchises.

We realize that some young people may be skeptical about formal education when they know that Bill Gates dropped out of Harvard to start Microsoft. But they should realize that at age 11, Gates began his preparation to become one of the most knowledgeable people on earth in personal-computing software. He invested thousands of hours in learning the expertise he would need. By the time he dropped out of Harvard, he was highly prepared. Attending universities, technical schools, and vocational schools and working with masters are still the best ways to rapidly gain high-leverage expertise. However, management is a particularly difficult field in which to discern high-leverage expertise.

The High-Leverage Expertise of Management

Management is complex work, and mastering its expertise is difficult. Peter F. Drucker defines high-leverage management expertise as the capability to do these things:

- Make people capable of joint performance.

- Make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant.

- Enable the enterprise and each of its members to grow and develop as needs and opportunities change.

- Build performance into the organization—think through, set, and exemplify objectives, values, and goals.

For more, see Drucker’s The Essential Drucker (New York: Harper Business, 2001).

Most executive managers began as individual contributors and then learned the expertise of each of the roles they had as they rose to higher responsibilities. They practiced what they learned, and they analyzed their successes and failures.

Does Too Much Focus Limit Us?

Some people say that when we focus too much, we become narrow thinkers. They say we should be generalists. We agree that it’s valuable to have knowledge of many fields and markets, but our research indicates that to find great opportunity, you should be a master of at least one or two. Edison and Walton had to learn many types of expertise to build great companies, but each of them had to achieve expertise in at least one field or market area before they broke through to greatness. With Edison, it was electromechanical invention; with Walton, it was discount retailing.

What Are the Most Powerful Ways to Learn Expertise?

Even when they focused on learning the high-leverage expertise of their fields or markets, the great achievers knew that they were still limited by time and the limits of their minds. So they found four powerful learning processes that allowed them to make the most of their limits:

- Devote quality time to learning.

- Manage the thoughts that occupy your mind.

- Use deep processing.

- Learn in the pursuit of opportunity.

These learning processes, of course, may not turn you into an Einstein. But without them, even Einstein wouldn’t have turned into an Einstein. He had a fine mind, but many fine minds never find greatness. It’s useful to look in detail at each of the powerful learning processes.

Devote Quality Time to Learning

The next great learner, Bruce Jenner, was a master of the process of devoting quality time to learning. In the 1972 Olympics, after placing 10th in the decathlon, he was watching a Russian receive the gold medal. Although disappointed after years of preparation, he asked himself what it would take to stand at the top of that platform.

Jenner decided to take every second of every day for the next four years and do only what would prepare him to win the Olympics. From then on, he used every spare moment to prepare—even placing a hurdle near his kitchen table so that he could rehearse jumping hurdles in his mind as he ate his meals.

At the 1976 Olympics, Jenner won the gold medal by the largest margin in history and set a new world record. This is an example of the ultimate in mind focus, and the ultimate in making the most of our limited time as humans. For more on Jenner, see his book Finding the Champion Within (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996).

All the great achievers have been acutely aware of the limits of their time. When the billionaire Bill Gates was asked what he could want more of, he said, “More time.” To get beyond the limits of time, we must find ways to increase the time we devote to learning and we must focus our whole beings on learning—as Jenner did.

There are major differences between the time management of the great achievers and those who accomplished less. Bill Gates also said, “My success in business has largely been the result of my ability to focus on long-term goals and ignore short-term distractions.” For more on Gates, see Bill Gates by Jonathan Gatlin (New York: Avon Books, 1999).

Everything requires time. It is the only truly universal condition. All work takes place in time and uses up time. Yet most people take for granted this unique, irreplaceable, and necessary resource.

—Peter F. Drucker

Fortunately, preparing to find most opportunities won’t take the devotion of a Jenner or an Einstein. However, it takes thousands of hours of study and experience to become a sought-after doctor, executive, chef, plumber, or teacher. The greater the opportunities we seek, the more time we must devote to preparation. Great opportunities seldom are found by the unprepared.

Because the great achievers realized the long-term benefits of preparation better than others, and also knew that they had little time, they devoted quality time to learning. To devote quality time to learning, you need to place learning high on your list of priorities; increase the percentage of time you devote to learning; focus completely when learning; and apply what you learn, measure the results, and relearn.

The second powerful learning process is more difficult to master.

Manage the Thoughts That Occupy Your Mind

Our brains can store unlimited knowledge and combine it in unlimited ways. They can process millions of subconscious thoughts per second. So why does it take more than 5,000 hours of study and experience to become a master plumber or machinist, 10,000 hours of education and experience to become a valuable knowledge worker, and far more than 10,000 hours of preparation for a career in law or medicine? If our brains are infinitely powerful, we need to understand why it takes so long.

It is often said that we use less than 10 percent of our brains and that if we could learn to use the rest, we would greatly increase our ability to think and create. The fact is that more than 90 percent of each brain directs billions of unconscious actions that take place in the daily routines of living. Picking up a cup of espresso, bringing it to your mouth, sipping, and returning the cup to its saucer require millions of small electrical and chemical reactions that are coordinated in the brain. Complex tasks, such as driving an automobile and hitting a golf ball, require the coordinated action of dozens of subsystems in the brain. Even the great achievers couldn’t use those parts of their brains effectively for thinking and creating. But 10 percent of their brains was enough, because they knew how to use that 10 percent well. There are at least three main reasons it takes so long to learn expertise.

One thought at a time. The first reason it takes so long to become an expert is that a brain can process only one conscious thought at a time. This is apparent to us when we forget what we just read or heard because another thought has entered our consciousness. We think of multiple things by alternating attention among them. We must store each thought and return to it a short time later—as if we’re pushing pause and play buttons on multiple mind recorders.

One thought per second. The second reason it takes so long to learn expertise is that a conscious mind can process only about one thought per second, while the subconscious is processing thousands of thoughts per second.

Subminds. The third reason for the long time it takes to learn is that our brains have hundreds of “subminds” operating below consciousness. When you overhear a conversation with the word “horrible” in it, see an attractive person, or think of something worrisome that your boss said, your submind goes into action. Brain researchers say that our subminds act independently, outside our conscious minds, and each wants to be the center of our conscious attention. (See the sidebar on Groucho Marx for an example of how subminds can intrude.) And for more on these topics, see The Evolution of Consciousness by Robert Ornstein (New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1991) and The Society of Mind by Marvin Minsky (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985).

Like the thought that entered Groucho’s mind, our subminds intrude like thieves in the night. They distract us and sap our productivity. They produce chemicals that excite and depress us. When they dominate our actions, we ignore preparation and decrease our chances of finding great opportunities in the future. We are so attracted by the exciting parts of our worlds that we don’t spend time creating our futures.

In a scene from a Groucho Marx movie, Groucho plays the leader of a small country that’s close to war. In the scene, Groucho is about to meet the ambassador of the other country. He’s confident that his peace offer will be accepted. But then Groucho begins talking to himself as he paces back and forth. “What if he snubs me by not shaking my hand? How will that look to my people? Why that cheap, no-good swine; he won’t get away with it.” By the time the ambassador arrives, Groucho is fuming. His first words to the ambassador are, “So, you refuse to shake hands with me!” He slaps the ambassador and starts a war.

If you want to get better control of the thoughts that enter your mind, you must learn to catch the uninvited intruders as they enter the brain. For example, any fire or crime you may hear about can grab your attention. You may want to find out if the police caught someone and, if they did,

- why he or she did it

- what kind of person he or she was

- what happened at the trial.

If you want to be in control of your time, you must track intrusions into your mind until you identify the top intrusion for a week. Then you must catch that intrusion and stop it each time it intrudes. This is difficult to do when modern media is swirling about us, competing for our attention while the expertise of any single area or field or market is increasing rapidly.

More than our grandparents, we must control what we allow into our minds, as Mihalyi Csikszentmahayli explains in Creativity (New York: HarperCollins, 1996). The great achievers could focus—they could choose to have only valuable thoughts in their minds.

As this book was being written, we received feedback that we made the keys seem like a big investment of time. The question was whether anyone could follow these keys if he or she is already busy with a job, a family, and other commitments.

Yet to find great opportunity, we must believe as the great achievers did that investment in learning brings large future benefits and increases opportunities. By using the preparation keys of the great achievers, whatever time the person spends on learning moves him or her rapidly on the path to opportunity. Somehow, we must carve out more time each day and devote it to learning our fields or markets. Even small amounts of time increase our chances of success.

Another question raised about the keys was where recreation fits in.

Recreation is good for the spirit. But a serious musician will spend a Sunday afternoon with a musical artist instead of attending a baseball game because he knows the value of preparation or he loves music first. To willingly devote the time to our fields or markets, we must choose work for which both learning and working are recreational. If you’re in work for which you have no passion, you must either change what you do or learn to love it.

The next learning process is the most powerful one: deep processing.

Use Deep Processing

To understand deep processing, it is important to first consider the popular method of “memory recall.” The brain is limited in its ability to store, combine, and recall memories. To get around these limitations, the early Greeks developed memorization techniques that are now universally taught. These techniques were made popular because of a terrible accident that took place at a banquet in 471 B.C. After reciting poetry to the assembled group, the poet Simonides was called outside to meet some men. While he was outside, the concrete roof of the banquet hall collapsed, crushing the guests within. When he was asked if he remembered any of the positions and names of the guests, Simonides reproduced the entire guest list and where each guest was seated.

When Simonides explained how he used a system of mental images based on the location of each guest around the table, his learning methods immediately became popular. Although the use of visual images for memorization is effective—to some degree—for almost everyone, some people remember better what they hear, what they touch, or what they feel emotionally. It is important to use memorization techniques that are best suited for you.

Although what Simonides did was remarkable, he was not being innovative; he was recalling images and facts. The ability to recall memories was not what enabled him to write epic poems. Rather, it was his ability to store memories so that they could be creatively retrieved later. It is important to understand the difference between recalling something and creatively retrieving it. Let’s look at an example of creative retrieval.

In 1935, Edgar Kaufman asked Frank Lloyd Wright to design a small summer home for him. But after Wright visited the site and had it surveyed, he did nothing. One day, Kaufman called him and said he was 40 miles away and would like to see the design. “Come on, Edgar,” Wright said. “We’re ready.”

Overhearing Wright’s conversation, two of his primary draftsmen couldn’t believe what he had promised. He had not drawn a single line. One draftsman, Edgar Tafel, detailed the scene that followed in his book Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979):

WRIGHT HUNG UP THE PHONE, WALKED TO THE DRAFTING ROOM AND STARTED TO DRAW, TALKING IN A CALM VOICE. “THEY WILL HAVE TEA ON THE BALCONY. . . . THEY’LL CROSS THE BRIDGE TO WALK INTO THE WOODS,” WRIGHT SAID. PENCILS WERE USED UP AS FAST AS WE COULD SHARPEN THEM. HE ERASED, OVERDREW, MODIFIED, FLIPPING SHEETS BACK AND FORTH. THEN HE TITLED IT ACROSS THE BOTTOM: FALLINGWATER.

TWO HOURS LATER, WHEN KAUFMANN ARRIVED, WRIGHT GREETED HIM AND SHOWED HIM THE FRONT ELEVATION. “WE’VE BEEN WAITING FOR YOU,” WRIGHT SAID.

THEY WENT TO LUNCH, AND WE DREW UP THE OTHER TWO ELEVATIONS. WHEN THEY CAME BACK, WRIGHT SHOWED KAUFMANN THE ADDED ELEVATIONS.

Wright’s Fallingwater made the front cover of Time magazine in January 1938. The house is built on top of a waterfall that cascades through the lower level. Wright and his team were able to produce an award-winning design in a few hours because they had vast stores of expertise in their memories that had been developed over decades and which they could creatively retrieve. The key lesson here is that they didn’t simply recall the memories they had stored; they retrieved new creative combinations of these memories—memories they had stored using a powerful learning tool: deep processing.

Research has shown that one’s ability to creatively retrieve memories is affected primarily by how one first puts something into memory. All the great achievers used deep processing to store expertise so that they could creatively retrieve it later. They processed information deeper in their brains than less successful people did. To deep process memories the way they did, you need to:

- Relate and compare what you’re learning to the expertise you already have.

- Ask yourself what is similar, what is different, what is new, what agrees with what you already know, and what does not.

- Go beyond the superficial and ask, what is the special meaning of this expertise to me, to others, and to society?

- Ask why you are better off knowing the expertise and what you can do with it.

- Question the expertise, think of its opposite, debate it with others, teach it, and review it several times in the coming days.

- Use your sight, your hearing, and your physical body to learn, but especially use the one that allows you to learn the best.

- Create images of the expertise in your mind combined with what you already know. Sketch the images or write descriptions of them.

- Learn with passion.

These findings are from Searching for Memory: The Brain, the Mind, and the Past by Daniel L. Schacter (New York: Basic Books, 1996). Some brain scientists, including Schacter, use the term “elaborative encoding” instead of “deep processing.”

When we deep process expertise into memory, all the memories stored earlier are enriched, because the new memories interact with the old ones, and accumulated expertise grows like ivy. So when we retrieve a deeply processed memory, we can get new, creative, valuable patterns without consciously recalling the individual memories that are combined. The subconscious mind is not bound by conscious rules, so it can make creative combinations of stored expertise that the conscious mind won’t allow.

When Simonides recalled the people at the banquet, he brought individual memories to consciousness. However, when Simonides wrote great poems and when Wright designed Fallingwater, they creatively combined deeply processed memories in their subconscious minds. Then they brought the new creative combinations to the conscious level. In essence, the great achievers were innovative primarily because they had great stores of deeply processed expertise that could be creatively combined in their subconscious minds. As we will see later in the book, they also had special ways to coax their brains to combine their deeply processed expertise in new and wonderful ways.

Learn in the Pursuit of Opportunity

The fourth powerful learning process that the great achievers used was learning in the pursuit of opportunity. The researcher Edgar Dale found that, two weeks after reading, hearing, or seeing something, we remember only 10 percent of it; see “Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience,” in Education Media by R. V. Wiman and W. C. Meierhenry (Columbus: Charles Merrill, 1969). However, if we discuss it with others, the level of retention is increased to 20 to 40 percent. Dale says that, when expertise has high meaning for us, when we have a purpose in learning it, and when we learn it directly through experience, we may remember as much as 60 percent of it two weeks later.

It has been consistently found that we learn the best and fastest when we are pursuing opportunities. Opportunity-finding and -seizing workshops are based on that principle. In these workshops, immediately after teaching the concepts and principles, it is important to help the participants find and seize the highest-leverage opportunities—whether for markets, leanness, personal development, or organizational development.

There are people who can recall detailed information they have only scanned and never really thought about. I'm not one of them. I have a good memory, though, for information that I've been deeply involved with or cared about.

—Bill Gates

Pursuing opportunities is the best way to learn, because a person

- learns with a purpose

- deep processes what is learned

- is directly engaged in an innovative process

- challenges his or her strengths, which increases them

- reinforces what is learned through successes and failures

- is passionate about what is being learned.

In this process, the hippocampus in the midbrain will decide to store information long term if we repeat it, if we dwell on it, or if it arouses emotion. If all three are strong, the memory may last a lifetime. This process of opportunity-driven learning is another reason that the great achievers, like Einstein and Wright, learned faster and better than others. They were always preparing for, finding, and seizing opportunities. They were in constant pursuit of opportunity.

In summary, deep processing and learning in the pursuit of opportunity are the two most effective power learning processes of the great innovators and achievers.

Secret Strategies?

Twenty years ago, when our research team was investigating what made people great, we suspected that the great achievers had secret strategies. The 10 keys could be considered secrets, not because the great achievers kept them secret but because only a few recognized their importance. Even when we began to teach adults how to apply these keys in their lives and organizations, many were skeptical. Since then, we have followed their careers and the success of their organizations. We have found that those who followed the path of these keys were more successful than those who didn’t.

Once you master these powerful learning processes, you can rapidly learn the expertise of the fields of work or markets that you have chosen. Or you can use them to change jobs or start new businesses. Either way, you would identify which knowledge and skills are the most important, and then you would devote quality time to learning and practicing them. You would deep process what you learn, relating and creatively combining it with the knowledge and skills you already have. Then you would be ready to search for opportunity.

Summary of Keys 1 and 2

To summarize so far:

- First, the great achievers chose to search for opportunity where they had the best chance of finding great opportunity.

- Second, they became expert insiders by using powerful learning processes to learn the high-leverage expertise of their work.

Key 3 of the great achievers is that they learned to envision opportunity. At the beginning of the 20th century, the next master we examine envisioned a great opportunity. After her discoveries, scientists had a new view of the atom. Her story begins on the most disappointing day of her life, at the end of four years of intensive research and backbreaking labor.

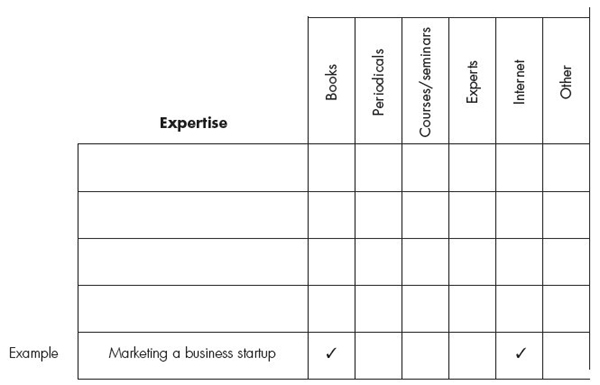

Self-Evaluation Exercise

Self-Evaluation Exercise

List your most valuable areas of expertise that pertain to opportunities listed in the exercises at end of the key 1 chapter and/or areas of interest to you. Write these in the left-hand column below. Expertise can be in the areas of emerging technologies, established technology, nontechnical, social, political, medical, industry specific, arts, education, and the like.

For each type of expertise, list one or more ways to pursue learning it by checking the corresponding boxes to its right.

Eliminate the pursuit of low-leverage expertise: Eliminate each category above if it is an area of interest only and is not tied to substantial rewards; eliminate it if only broad knowledge is required and you have access to other experts in that category; eliminate it if there is no tangible return on effort or market need for the result of gaining expertise in this category.

Within the remaining types of expertise listed above, list one area of this field of expertise that would be most effective to learn if you could only dedicate one hour a week to learning it; these are your high-leverage areas of expertise.