Key 6

Co-Create with People

Eager for Opportunity

People support what they create.

—Kurt Lewin

Great leaders have the answer to the question: How do we influence those who are most eager to invest? They are often those who eagerly seek opportunity, have high motivation to create change, and will influence others.

How Do We Influence Those Most Eager to Invest?

The next great innovator’s ability to influence those most eager to invest was critical to his seizing a great opportunity. His story begins at the moment he faced bankruptcy.

After months of preparation, in early 1973, Fred Smith, his wife, and his office staff stood at the end of a runway on a small airfield in Memphis, Tennessee. They were waiting for six small jets to arrive with packages to be delivered overnight. A makeshift con-veyor and sorting table were set up in an old hangar, and employees were standing by. Everyone knew that this was the last chance. All day, reports from sales agents had been optimistic, and Smith was ready to celebrate. Just before midnight, six tiny lights appeared in the sky. After the jets landed and roared to a stop, everyone moved toward them. When the doors of the first plane were opened, the group looked into the cargo hold to see the contents.

Empty! They looked into the other planes; there were only five paid packages. The group couldn’t believe it. Smith was shocked. Surely now, his family, financial backers, friends, and staff believed, he would come to his senses, give up overnight package delivery, and do something else for a living. Three strikes in the overnight delivery business and you’re out.

Smith’s first attempt to make overnight deliveries was carrying securities for bond houses. But when insurers wouldn’t guarantee those shipments, his business fizzled. Then he decided to fly checks between Federal Reserve branch banks. The Federal Reserve branches encouraged him because they could envision big savings. But by the time he had bought two airplanes, named his company Federal Express (FedEx), and was ready with a working system, the Federal Reserve had scrapped the idea.

Then Smith came up with the idea of overnight package delivery. His company would pick up packages, fly them to Memphis and sort them, and then deliver them to their destinations the next morning. Fred chose six cities close to Memphis for his trial run. He bought four more planes, expanded his crew, and hired a salesforce. The result was those six planes with only the five paid packages.

On the edge of bankruptcy, Smith asked his team members to stick with the business and to invest their time to help him create a successful overnight delivery business. They agreed. After two weeks of 16-hours-a-day analysis, the team members decided they had chosen the wrong cities to start with. They had chosen cities a short flight from Memphis rather than cities that needed the air freight service. For example, they’d picked New Orleans, which had a weak industrial base and was well serviced by Delta Airlines. So they searched for cities with strong industries but poor air service— like Rochester, New York, the home of Kodak and Xerox—that most needed overnight delivery.

In April, Smith and his team gathered again at midnight at the airport and waited for the planes to return from the newly selected destinations. They all agreed that they had given it their best shot. If it didn’t work this time, they were through. After the planes rolled to a stop, the group quietly approached. When the first plane’s cargo doors were opened, they again pressed to look into the hold. They were surprised and elated; the planes were filled with hundreds of packages. The team’s plan had worked, and they now were committed, for better or worse.

Shortly afterward, it did get worse. In one crisis, while juggling his cash to keep the company afloat, Smith issued a memo with all employees’ paychecks, stating that they were welcome to cash their checks but that it would be helpful if some of them waited a few days. Almost everyone waited. Some employees never cashed those checks. Many of them proudly have the framed checks hanging on their office walls.

Smith’s team continued to fight its way through obstacles until FedEx was delivering thousands of packages each day. It was the fastest company in history to reach $1 billion in sales. Today, FedEx delivers 2.5 million packages a day and is a $24 billion enterprise, according to its 2004 annual report.

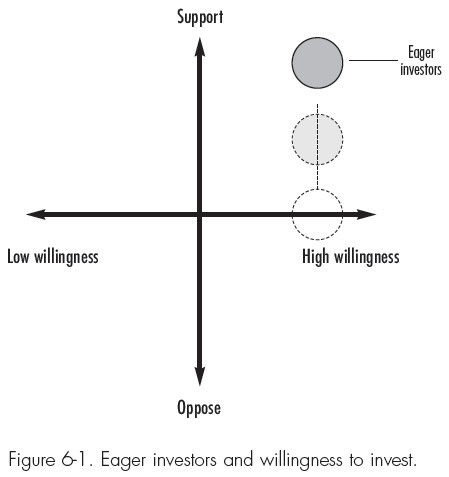

Great leaders like Fred Smith know how to influence those who are eager for opportunity, those who are often called “early adopters.” When those eager for opportunity are willing to invest, they’ll influence others to invest. In figure 6-1, the darkest shaded circle at the top right represents the results of properly co-creating with these eager investors—who have the most potential of the three investor groups to become great supporters. The effective use of the techniques described here usually moves this group up toward support, as the two other circles in the figure show.

Co-Creation

Effective leaders like Fred Smith work with those who are eager for opportunity to jointly create the opportunity, so they are willing to invest in seizing it. We call this co-creation. Co-creation works because, as Kurt Lewin said, “People support what they create.” And everyone has something creative to contribute, which leads to a first law of meaning.

The First Law of Meaning: People support what they create. Co-creation is a timeless key. In A.D. 100, Columella, a Roman landlord, wrote about managing his workforce: “Nowadays, I make it a practice to call them into consultation on any new work. I observe they’re more willing to set about a piece of work when their opinions are asked and their advice followed.”

Centuries later, the genius inventor Thomas Edison co-created with his team. A machinist who worked for Edison for 50 years said, “He made me feel I was making something with him; not just a workman.”

By building environments that favor co-creation, organizations increase their chances that eager investors will step forward and invest their time and ideas. For example, in the late 1980s, NASA asked Lockheed Martin to cut the weight of the huge fuel tank that forms the backbone of the space shuttle. An engineering team used stronger, lighter-weight materials to reduce the weight but fell 800 pounds short of the target. However, the team had widely dispersed the knowledge of the weight-cut target to the workforce. One line worker knew that 200 gallons of paint was being used to paint the tank, and he knew that a gallon weighed about 4 pounds, amounting to a total weight of 800 pounds. He also knew the tank had a 10-minute lifespan before it was jettisoned. He suggested that they stop painting the tank. The engineers listened, and NASA agreed. The line worker invested his idea in the effort because the Lockheed Martin managers were open to co-creation.

Few leaders are better at co-creation than Norman Bodek, the founder of Productivity Inc. and the acknowledged founding father in this country of the “lean” movement, which follows a system of principles to eliminate waste and generally do more with less. These principles are built on Toyota’s production system and the lessons it learned from U.S. auto manufacturers in the 1950s. “Lean,” thus, usually refers to highly productive business systems that are customer focused, with low inventory, quick turnaround, and few defects.

In the early 1980s, Bodek introduced American business to these very productive lean methods. He believes that every person has the capacity and desire to be a problem solver and to be a source of creative ideas. His mission was once suggested in a Chinese fortune cookie: “You have the talent to recognize the talent in others.”

With many great successes to his credit, Bodek now spends his time teaching managers how to help people use their creative abilities. He founded the publishing company PCS Press to spread his message. “I see myself,” he says, “as the Johnny Appleseed of empowering people to believe in themselves and their creative abilities.”

Toward Key 7

We’re now ready for the great achievers’ key 7. To prepare for this key, recall the times you have seen leaders fail, even though they have the willing support of “eager investors.”

Even adventuresome people have difficulty changing what’s been good to them for many years. Even when logic says “change or else” or when the situation is highly uncomfortable, they may hold on to the way things are. Either they have a lot invested in the way things are or they’ve experienced too much change lately. Or maybe they don’t mind change but they mind being changed. Most people are not easily changed; they are cautious and pragmatic. Let’s examine why they’re cautious.