Key 8

Negotiate in Advance with Potential Opposers

Most people hate resistance. Because it is viewed so negatively,

people want to get over it. In the words of many articles on the subject,

people want to overcome resistance. This view is wrong.

Attempts to overcome it usually make it worse.

—Rick Maurer, Beyond the Wall of Resistance

Great leaders know that opposers are simply protecting what has meaning to them or are champions of other opportunities that are competing for the same resources. So they study what the other opportunities offer and they search for ways to either convert the opposers or reduce their negative effects. However, like Galileo, leaders sometimes take the worst approach with those who oppose them. But this leads to a question: What’s the best way to convert or reduce the negative effects of those who want to stop us from seizing opportunity? Let’s look at the answer to this question.

What’s the Best Way to Convert or Reduce the Negative Effects of Those Who Want to Stop Us From Seizing Opportunity?

The great innovators and achievers found three ways to convert or reduce the negative effects of those who wanted to stop them from seizing opportunities:

- Include opposing viewpoints.

- Find common meaning with opposers.

- Use force only as a last resort.

Include Opposing Viewpoints

In its short history, the United States has faced several crises that have threatened its existence. In each crisis, a leader emerged who was able to bring together opposing sides to seize the opportunity to survive. Let’s look at two of these crises.

Hamilton faces the bankruptcy crisis. In April 1789, the newly formed U.S. government was sinking into bankruptcy. During the Revolutionary War, the federal government and the newly formed states had borrowed heavily to finance their efforts. Immediately after being sworn in as the first president, George Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton as secretary of the Treasury and asked him to tackle the problem.

Hamilton proposed that the federal government assume the debts of all the states. He believed this would forge the states together in a lasting union. But James Madison lashed out at Hamilton’s proposal, saying that, because his home state and some other southern states had already paid off their wartime debts, they would be contributing to those states that hadn’t done their duty. Many members of Congress saw that if Hamilton had his way, the federal government would become the central taxing authority. Congress voted down Hamilton’s proposal.

But Hamilton didn’t give up. He knew that the location for the nation’s capital was a leverage point because it would bring great power, wealth, and population to the area chosen. At the time, there were two likely sites for the nation’s capital: Philadelphia, because it had been the site of the Continental Congress and the drafting of the Declaration of Independence; and Virginia, the home state of Madison and Thomas Jefferson. He cut deals with the Pennsylvania and the Virginia delegations to vote for his proposal in exchange for his influence in locating the capital temporarily in Philadelphia, with a permanent location to be constructed later along the Potomac River.

With this tentative compromise in mind, Hamilton went to Jefferson and Madison and told them that the northern states were threatening secession if the capital was located in the South, but that he and President Washington would support the capital in Virginia if they and the southern states would support his proposal to have the federal government assume all wartime debts. They agreed, and the proposal passed in Congress. Jefferson said that he regretted this decision more than any other in his life, because he later realized that Hamilton’s plan centralized great power in the federal government.

Hamilton was not only a great financial thinker; he was also a great negotiator. He knew that Madison and Jefferson would not risk having the northern states secede, no matter how badly they wanted the capital in Virginia. They needed his support to get the capital without secession, no matter how much they were opposed to his plan.

Kennedy faces the missile crisis. Another crisis took place in late 1962. U.S. spy planes flying over Cuba took pictures showing that the Cubans were building a nuclear missile installation from which they could reach most U.S. cities. President John F. Kennedy put a team together to analyze the situation and recommend action. By the end of the first day, it was nearly unanimous that the United States should launch a surprise air attack, followed by an invasion.

But Kennedy knew that Soviet soldiers at the missile installation would be killed by air strikes, which would escalate the situation to a U.S.–Soviet conflict. He and his brother Robert (“Bobby”) remembered a disastrous decision they had made 18 months earlier, when they decided to secretly help a band of Cuban exiles invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had predicted that people in Cuba would join the invading force and then rise up and overthrow Cuban President Fidel Castro.

But the Bay of Pigs invasion had been a disaster. The Cuban military captured the invaders and then humiliated them by parading them through the streets of Havana. When President Kennedy appointed a blue ribbon committee to find out what had gone wrong, the committee members said that the president was to blame because he decided on an answer before weighing alternatives. They also said that his brother Bobby had shut off all Cabinet opposition to the invasion. The brothers were so shaken by this report that they changed their fundamental approach to decision making—never again deciding on an answer until all the options had been developed and all opposers’ viewpoints had been considered.

So, during the missile crisis, Bobby Kennedy asked the team to come up with other responses. On the third day of struggling for options, someone suggested a limited blockade as a first step. Some members of the group thought that a limited blockade would open a window for negotiation. Others saw it as a first step toward an air strike, an ultimatum. Eventually, the whole group agreed on a limited blockade as a first step.

The next day, President Kennedy presented the plan to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, saying that the blockade would serve as an ultimatum, followed by air strikes if needed. He talked to the congressional leaders and then went on worldwide television and radio to announce a shipping quarantine of Cuba. He said that ships entering the quarantine zone would be stopped and searched. He warned that if any missiles were fired from Cuba, the United States would launch a nuclear strike against the Soviet Union.

In the next few days, the world held its breath as Soviet ships headed toward the blockade. At the last minute, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev turned the ships around and offered to remove the missiles in return for a U.S. promise not to invade Cuba. When one of Kennedy’s team heard that the ships had turned around, he said, “We’ve just had a showdown, and the other guy blinked.”

Recently declassified Soviet and U.S. documents indicate that the situation was more dangerous than the Kennedys imagined. Secret memos from Khrushchev show he was worried that he couldn’t control Soviet officers in Cuba. The CIA estimated Soviet troop strength in Cuba at only a few thousand lightly armed men. But Soviet documents reveal that there were 40,000 Soviet troops in Cuba at the time, equipped with battlefield nuclear weapons. An air strike or invasion could have triggered Armageddon.

President Kennedy learned the importance of listening to opposing views and negotiating for solutions that took advantage of the collective wisdom of his advisers.

Find Common Meaning With Potential Opposers

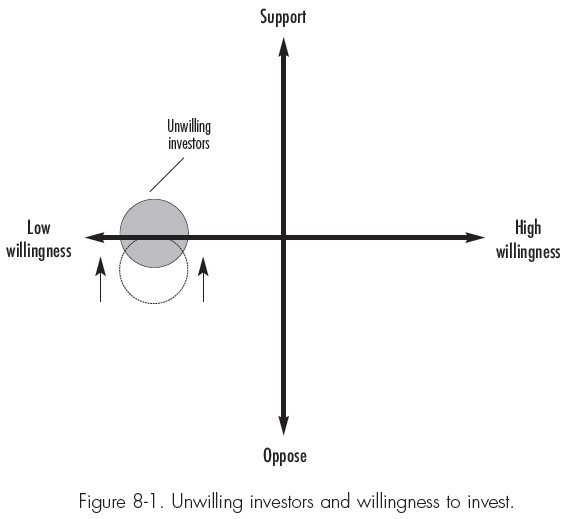

Unwilling investors have a tendency to oppose new opportunities, as is shown in figure 8-1, where they are represented by the lower circle drawn with the dotted line. The use of good techniques can move them from this opposition up to a more neutral position, shown by the shaded circle. Avoiding this group or the use of poor techniques can cause strong opposition to the opportunity that you are pursuing.

In facing crises, both Hamilton and Kennedy used powerful negotiation techniques to bring opposing sides together—in effect, creating a win-win situation (see the sidebar). Earlier in the book, we presented some recommendations for searching for meaning. The same recommendations apply to negotiating with opposers, with the addition of the following:

- Assume that opposers have legitimate reasons for their positions and their interests.

- Find the minimum terms that each opposer will accept.

- Find a common need or want.

- Negotiate a win-win plan if you can.

- Think of alternatives if you can’t get a settlement. What will you do if either side refuses to budge, walks away, or escalates its opposition? Is time on your side or against you?

There are those who feel that win-win thinking is weak-minded—that winning is the only thing. They believe that the best negotiators are those who can negotiate the lion’s share. They view negotiation as a contest where the “best” party wins at others’ expense. The tactics of such win-lose negotiators are to negotiate from a position of strength, to set their demands so high initially that the final negotiated settlement is biased in their favor, and to act as if time is on their side.

For nearly 100 years, beginning with violent strikes against the auto companies and recent strikes in American sports, union-management contract negotiations have been plagued by adversarial negotiating. On the one hand, these are usually costly to all stakeholders. Many have led to permanent losses of jobs, the termination of unions, company bankruptcies, and the loss of customers. In other words, there is a high risk that adversarial negotiation will end in lose-lose. On the other hand, some believe that every opportunity creates winners and losers. The expression, “You can’t make an omelet without cracking a few eggs” is often used to justify this position.

Steven Covey says that win-win leaders see life more as a cooperative —not a competitive—arena, and that win-win thinking “is based on a belief that there is plenty for everybody, that one person’s success is not achieved at the expense or exclusion of the success of others.” See his book The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People (New York: Fireside, 1989).

Win-win negotiators view negotiation as another form of co-creation.

The toughest leaders don’t negotiate with the opposition; they fire them. That sends a message. Then everyone’s willing to do whatever it takes to keep his or her job. However, fear won’t convert someone into a willing investor, especially if he or she has other opportunities. Fearful people may do what it takes to survive; but instead of devoting their creativity to seizing the opportunity, they may devote it to quietly sabotaging it. Even worse, creative people will leave organizations that dictate what they must do. The best leaders design the opportunity with all involved so that everyone gains from seizing it. That’s win-win thinking.

Over a period of time, an organization that uses the keys to mobilize people’s support increases its number of eager investors and their overall willingness to change. At the same time, it decreases the number of people in the organization who are opposed to change. Over time, as the organization increases its number of eager investors, it sees the opportunities in the changing world and creates its own future. But an organization that fears and opposes change will have its future created for it.

In extreme cases, opposers will put you in prison or kill you if you seize the opportunity they oppose. In such cases, it takes great heroism to begin the seizing process. Occasionally a hero will arise, risk all, and plant seeds for change that profoundly alter the course of history.

A hero arises. One great hero arose in China in 1978, when farmers in the village of Xiaogang were starving. Chinese law forced them to turn their crops over to the government in exchange for such small amounts of grain that they could not feed their families.

Witnessing this starvation, Yan Hongchang, the village leader, decided that death by starvation was so terrible that any punishment the government would inflict for violating the law could not be worse. He persuaded 18 farmers to sign a pact that divided their land into family plots. They promised to turn their production quotas in to be given to the government, but they would keep whatever remained—a violation of Chinese law. The agreement also said: “In the case of failure, we are prepared for death or prison, and other commune members vow to raise our children until they are 18 years old.”

In 1979, the leader of the commune of 10,000 members, which included Yan’s village, accused the village of “digging up the cornerstone of the Revolution.” In desperation, Yan went to Chen, his county’s Communist Party secretary and a man with a reputation for having an open mind, and begged for help. Chen had heard that the group’s harvests were good, so he agreed to protect the village as long as the practice didn’t spread. Eventually, however, word of the violation made its way to Beijing and to China’s new premier, Deng Xiaoping. The villagers braced for the worst.

Deng surprised everyone. Instead of meting out punishment, he was so impressed with what the villagers had accomplished that he applauded them and directed that they be used as an example of what the Chinese farmer could do.

From heroism to pragmatism. Years later, when Deng reflected on the rise of the village entrepreneurs, he was especially candid. He said, “It was if a strange army appeared in the countryside, making and selling a huge variety of products. This is not the achievement of our central government. . . . This was not something I figured out. . . . This was a surprise.”

The new philosophy of pragmatism that Deng sanctioned—believing that a method is good if it produces good economic results—has spread throughout China and is fueling the largest industrial revolution in history.

So if the opposers can destroy your life, it helps to seize an opportunity that is also a “win” for them. It also helps to have a temporary protector to shield you until the rewards are delivered.

Use Force Only as a Last Resort

When leaders become frustrated with opposition, they may react with force. The problem is the word “force”! Rick Maurer, a change consultant, says that people lose their effectiveness when they react to resistance by

- using power

- manipulating those who oppose

- applying the force of reason

- ignoring resistance

- playing off relationships

- making deals

- killing the messenger.

There is a common thread in these reactions: They’re all intended to overcome resistance. But these reactions don’t sell the opportunity to cautious investors, nor will they help you find common meaning and negotiate with opposers. On this topic, you might want to read more by Maurer, who introduced us to the concept of embracing resistance. He has concluded from his research that the ability to embrace resistance is a key secret of those who are able to go beyond the “wall of resistance.” See his book Beyond the Wall of Resistance (Austin: Bard Books, 1996). This leads to a third law of meaning, which applies to opposers.

The Third Law of Meaning: The more we force opposers to give up what has high meaning to them, the more they may resist. Leaders are at their best when they’re co-creating, selling, and finding common meaning. They search for meanings that the opportunity can have for all with a stake in it. They encourage people to express their needs, hopes, aspirations, concerns, and fears. They relax in the face of opposing views, letting others know that it is OK to express opposition.

Do you, the reader, have negative feelings when

- your views are questioned or attacked?

- your motives or intentions are denounced?

- others don’t trust you?

- they say they can’t or won’t do what’s asked of them?

- they say it can’t be done?

- they try to sabotage the effort you are leading?

Summary of Keys 5 through 8

To summarize keys 5 through 8, great leaders

- search for the highest meanings of those who have a stake in the opportunity

- co-create the opportunity with them so that it produces the largest rewards they can get for their investment

- sell opportunity to cautious people by helping them see how they must change to seize new opportunities

- negotiate with opposers to minimize their resistance.

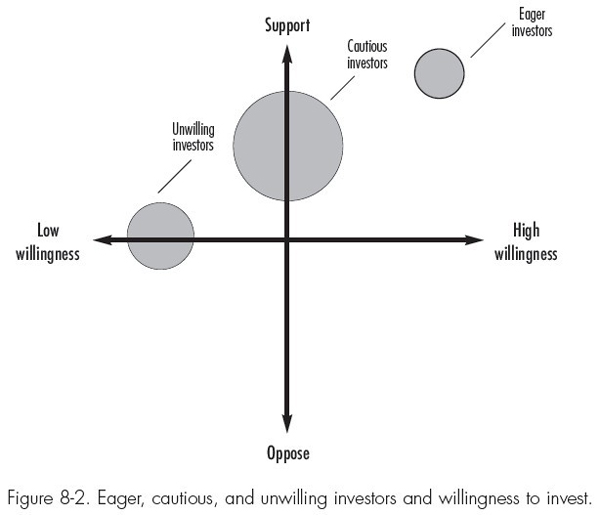

Figure 8-2 shows typical results from effectively mobilizing support to reduce the negative effects of unwilling investors, the large effects of selling to cautious investors, and creating enthusiastic support from highly willing eager investors.

Great leaders help all stakeholders find and seize the highest-leverage opportunities with the highest meaning.

Building a Bridge

Between finding an opportunity and seizing an opportunity, there is a great canyon that swallows most opportunity finders. Building a bridge across this canyon is the work of leaders, designers, and implementers. The seizing process is like a military battle. You can plan it and manage it, but once the battle begins, you must lead it in a high-leverage, high-meaning way, as discussed in detail in part III of this book.

Self-Evaluation Exercise

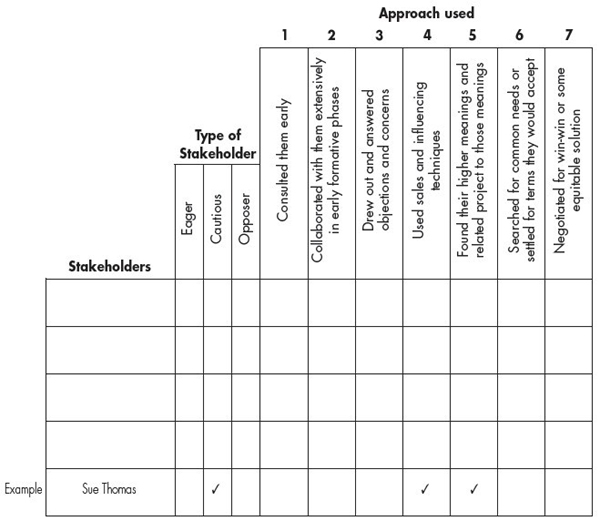

Self-Evaluation Exercise

Below, list the key people—the stakeholders—who were involved in your last project or endeavor in the left-hand column. Then check the box that indicates the type of stakeholder they are—eager, cautious, or opposer. Finally, check the boxes of any approaches you used with them on the seven right-hand columns.

The approach used for eager stakeholders should be mostly from columns 1 and 2. Likewise, for cautious stakeholders, columns 3, 4, and 5 should be used. For opposers, the approach should be from columns 6 and 7.