When considering this chapter, I wondered if I was getting a little too tactical. I am providing one view into what it takes to knock out a TV or radio spot, but that’s not really what this book is about. As a whole, my rationale for creating this book was to help creative directors and other creative leads prepare for leadership. If I were to consider writing chapters for every element that lies within the realm of a creative lead I would have chapters on design software, illustration, poster design, editorial design… and much more than could fit into one book.

So, why did I get tactical with a 30-second TV or radio spot and dedicate a chapter to them? Because producing elements for broadcast is one of the skills that creative directors must excel at, but it’s not something typically taught to them in school. Students that are going through design school or a creative sequence are required to take courses in art direction, typography, interactive media, digital illustration, or animation. Students interested in becoming copywriters will take courses in marketing, creativity, American culture, the psychology of advertising, or design of integrated communications. Whether studying to be a visual or verbal creative, students are offered classes concentrating on the skills for their particular focus, but working on TV spots or radio spots isn’t part of their curriculum.

The Bottom Line

Yes, I know. People usually put the bottom line at the end of their process, but I’m adding it here. Here’s the bottom line about working on TV or radio spots: You and your team are going to work your asses off during every stage of the process, from the initial client brief through post-production. You have to pay attention to every single detail at all times. Every decision you make needs your full attention because a shoot can go awry very quickly. When you’ve finished shooting, unless you have a client with an unlimited budget, there is no going back to reshoot. Keep your eyes open. Make your decisions count. When you think you’ve done everything you can, double- and triple-check everything. If you let up at any time, there is a risk the spot will suffer. It’s exhausting but when you have a great spot all the hard work is worth it.

The Creative Brief

Every great journey begins with a story, and for the 30-second spot, that story lives in the creative brief. A creative brief is a document that is produced as a result of initial meetings and discussions between a client and the agency before any work begins. A good creative brief answers several questions: What is this project? Who is project speaking to? Why are we engaging in this project? Where and how will it be used? Throughout the creation of the project, the creative brief always provides the guidelines for the work.

Creative directors along with Account Service will be involved in composing the brief. A good creative leader can tell when there is fertile ground in a strategy. There will be nuggets of information that will get you thinking about different possibilities for creative solutions. As you come up with these key insights, when you add them to the brief, they will in turn, get your creative team energized and actively ideating solutions.

Yes, creative briefs may be tedious to work on, but it will make the entire creative process a whole lot easier in the end. For smaller jobs for clients with whom you have a long history, it may not be necessary to have a creative brief. You may know their brand standards, their voice, the visuals they utilize, and so on, and you can lead your team with a simple work order from Account Service. However, when beginning a large job or working on a TV spot, a creative brief is imperative, because it helps ground your team and gives them parameters to strive for.

Here are a few reasons that you’ll want to ensure that there is a creative brief produced:

It gets your client and creative team in alignment. It allows the client to understand the creative aspects that will be addressed and your creative team to understand what the client’s goals and parameters are for the project.

It helps make the creative process run a little faster because it will clear up any potential misunderstandings before the project commences.

It places responsibility on specific people because it clearly outlines every aspect of the project and who is responsible for each portion of it. This guarantees accountability.

A brief can minimize the approval process because the creative that is produced for client sign-off will be aligned with the previously approved brief.

It guarantees a better outcome because preplanning and aligning to the brief allow the entire team to avoid unnecessary risks and problems that could take their focus away from the most important aspects of the gig.

When you receive a creative brief to get the work started, it should be relatively short. You don’t want to provide too much information because it can be overwhelming. You want to have enough room for your creative team to play. When you’re working with your planner or your account team to develop the creative brief, you should strive to keep it very targeted and succinct. If you can keep the brief to one page, you will have an easier time getting to the meat of the assignment. The brief should get to the key insight. What is it about the client, product, or service that the brief is really trying to get across to the public? The more specific the problem to be solved, the better. For example, instead of a brief that revolves around the idea “beer is good,” provide a brief that revolves around the idea “beer is good because it doesn’t fill you up.”

The brief should provide the following information about the client and the assignment:

Key Fact: What is the key insight about the client, product, or service that the creative team can build their ideas on?

Problem: What is the problem that the campaign will solve? (e.g., too many people are texting while they are driving)

Objective: What is the campaign trying to accomplish? (e.g., decrease the number of people who text while driving)

Key Benefit, Promise, or Offer: What is the benefit that the target audience will experience because of the campaign? (e.g., decreasing the amount of texting on the roads can lead to fewer traffic accidents due to distracted driving)

Support Information: Are there any stats that support the problem?

Tone: What is the overall feeling of the campaign? (i.e., happy, sad, serious, informative, upbeat, etc.)

Target: Who is the campaign speaking to?

Competition: What are the client’s competitors doing in the market?

Mandatories: What must be done/shown? (i.e., logo, tagline, music, graphics, etc.)

Whatever you do, don’t let your excitement for getting a new project allow you to run amok and start ideating before a creative brief has been created. Take it one step at a time. Wait for the brief so you have a path to follow. In the end, doing so will save you a lot of time, frustration, and money.

One last insight: Agency production should be involved once you begin solidifying the concepts. Production is an integral part of the creative department. If they are there when you have the smallest spark of an idea beginning to form, they can start thinking about how to get it accomplished.

The Creative Process

Complete immersion in the product is a must if you and your team are going to ideate and produce work that is true to the brand and relevant to the consumer. To help your team get immersed in the project you will need to help them with research. If you don’t have a planning department to provide you with research, you will need to do your own and disseminate it to your creative team. Some creative leads begin with an intuitive search online. They begin with the client and then start fishing around with a keyword search to generate a pool of visuals that can inspire their creative solutions.

To get started, I typically spend quite a bit of time writing down everything I know about the client, their target audience, and their marketing objective. This is not an exercise to begin with ideation. It’s simply a way to get all of the information I know about the client out in the open. Once I put everything down on paper, I leave it behind for a while. While I am off doing other things, I allow myself to process the information and ideas start rising to the surface.

Next, I like to get a little more concrete with my ideas and start to write them out so they aren’t merely abstract thoughts and visuals roaming around in my head without any real purpose. When I have my initial thoughts in a somewhat comprehensible format, I engage one of my creative team members. I typically choose a person who is suited for the marketing challenge, whether that be a design challenge, a communications challenge, a web challenge, or a broadcast challenge. If you want more about this part of the creative process, check out Chapter 5.

As you’re working through the process, you’ll likely find that a lot of ideas pop up in the beginning. Most of these you should throw out. If they are the first ideas that come to mind, chances are they are not very insightful and could have been thought up by anyone. Keep working at it, and eventually you will have a breakthrough. Ideas will flow from you like someone just opened a fire hydrant in the neighborhood.

Storyboards

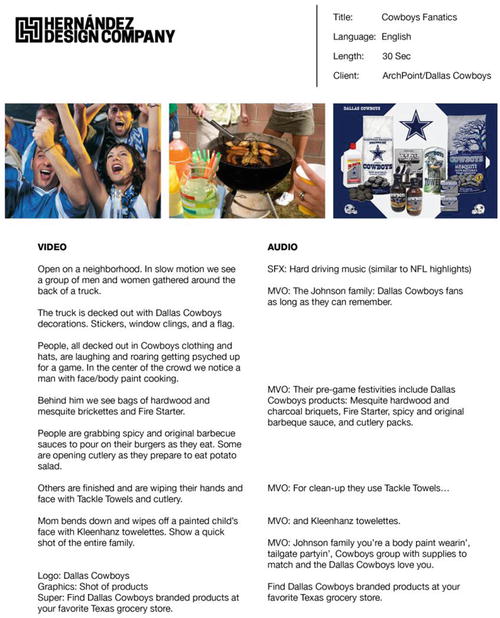

Storyboards are visual references used in the creation of a TV spot (Figure 10-1). They are used throughout the ideation, development, and production process. The storyboard will first be used as a visual piece presented to your client for approval. Once past that stage, it will be used by your production company to help them create their visual treatments for agency approval. Finally, once filming begins, the storyboard acts as a roadmap of the initial concept that must be used to ensure that the overall message and initial concept are not lost in the translation from static boards to completed spots.

Figure 10-1. Storyboard for a 30-second TV spot

Because storyboards provide the template or bible for the shoot, they must be clear and easily understood by everyone involved in the production. Shorthand or jargon only understood by you and your team has no place on the storyboard. Always create storyboards that can relay the key information of the concept without you having to explaining them.

In addition to universally understood storyboards, you must also be able to speak the lingo. You should understand shot list terminology to be able to describe the specific camera movements and angles that can add to the effectiveness of your spot.

Shot List Terminology

When you’re working on a storyboard to give to your production company, you can add terminology that will explain exactly what you’re thinking using few words. Familiarity with the language of filmmaking is key to creating concise descriptions of each shot and avoiding the miscommunication or faulty assumptions that can be costly in terms of time and money. The following is a list of useful terms and definitions that are organized into categories of scale, angle, movement, and transition. Keep in mind that these shot terms are for your reference and should never be used when pitching an idea to a client. For more on this, refer to Chapter 8.

Scale

Extreme close-up (ECU): A shot with a very narrow field of view that gives the impression that the camera is very close (Figure 10-2). For example, a shot of a person’s eyes.

Figure 10-2. Extreme close-up (ECU)

Close-up (CU): Same as ECU, but with a slightly larger field of view. For example, a shot of a person’s head and shoulders.

Medium shot (MS): A shot where the field of view is between the long shot and the close-up (big surprise, I know). The actor is typically viewed from the waist up.

American / Hollywood / cowboy or knee shot: A shot that frames the talent from the knees up.

Full figure: Shot composed with the entire human figure in frame (Figure 10-3).

Figure 10-3. Full figure

Long shot (LS): A shot giving a broad view of the visual field. The subject appears to be far away from the camera.

Wide shot (WS): A shot that shows a wide vista. (i.e., a horizon)

Single: A shot with only one person.

Two shot: A shot with two people in it.

Insert: Often shot by a second camera, this shot typically reveals details either not seen in the master shot or missed by general coverage. (e.g., a hand pulling money out of a wallet)

Two-T shot: A shot framed from the nipples up. (Call me immature, but this definition always makes me giggle.)

Angle

High angle: A shot taken from an angle above the object.

Aerial shot: A very high angle shot, now typically accomplished with a drone.

Low angle: A shot taken from an angle that places the camera below the object or subject (Figure 10-4).

Figure 10-4. Low angle

High Hat shot: An extremely low angle shot positioned as if the camera were sitting on top of a tall hat on the ground. This view is named after a piece of equipment that is designed to hold the camera on the floor.

Profile: Shot from a side angle.

Straight on or frontal: When the camera angle is directly facing the subject or object.

3/4 shot: A shot positioned halfway between a directly frontal angle and a profile that can be taken from the front or behind.

Over-the-shoulder shot (OTS): A shot taken from over a character’s shoulder, many times used during a conversation with another character.

Camera Moves

Dolly shot: Also known as a Tracking or Trucking shot. The camera rolls on dolly tracks. Usually used to record shots moving on the z axis (pushing in or pulling out).

Pan: The camera swivels on the horizontal x axis, often to follow the action.

Swish pan: A very swift pan that blurs the scene in between the starting and ending points.

Tracking shot: Camera moves to the left or right. Typically used to follow a figure or vehicle.

Tilt: The camera pivots up and down from its base.

Boom shot: The camera travels up and down on a boom arm.

Crane shot: A shot taken from a crane that has the ability to boom down and track in long distances without using tracks.

Car mount: A shot taken from an apparatus that is mounted to a car.

Static shot: Any shot where the camera does not move.

Steadicam shot: A shot using the Steadicam, a camera that attaches to a harness and can be operated by a single person in handheld situations. The shots taken appear to have been done with the smoothness of a tracking shot.

Zoom: The movement of a zoom lens to bring the subject closer (Figure 10-5).

Figure 10-5. Zoom

Zolly: A technique in which the camera dollies in and zooms out at the same time, or the reverse (zooms in and dollies out simultaneously).

Smash zoom: A very fast zoom.

Handheld: The operator braces the camera on the shoulder or at hip height.

Follow shot: Any moving shot that follows the actor.

Traveling shot: Any shot that utilizes a moving camera body.

Editing, Transitions, and Camera Point of View

Objective shot: The camera sees the scene from an angle not seen by a character in the scene.

Subjective shot: A shot taken from the position of someone in the scene. A Point of View (POV) shot is an example of a subjective shot.

Master shot: Also known as a Cover shot. Typically a medium- to wide-angle shot of a scene that runs for the duration of the action.

Establishing shot: Many times this is a wide shot of the location used to tell the audience where they are (Figure 10-6).

Figure 10-6. Establishing shot

Coverage: All the setups needed to edit the scene.

Offscreen (OS): Describes what is heard but not seen on the screen.

Reaction shot: Usually a close-up of a character reacting silently to actions they have just seen or dialogue they are hearing.

Cutaway: An editing term used to define information not seen in the master or previous shot.

Jump cut: An editing term for successive shots that can cut in on the same axis. It can also be used to describe successive cuts that disrupt the flow of time or space.

Match cut or Match Dissolve: Cutting or dissolving from one similar composition to another.

Point of View (POV) shot: The camera angle takes the view of a character in the scene.

Reverse angle: A shot that is 180 degrees opposite the preceding shot.

Budgets

When you’re working with your team to ideate TV spots, nobody ever wants to have budget constraints hamper the creative process. The reality, however, is that you have to continually aware of how much money your client has to spend and how best to allocate that money to get the job done. You should work closely with your account team to see if they have received a budget amount from the client to help you gauge whether the ideas you’d like to move forward with are feasible or not.

To develop your budget, you’ll need to know what it’s going to cost to produce the commercial and what it’ll cost to air after it’s completed. The cost to produce and air a TV spot will vary depending on several factors such as the following:

How elaborate do the spots need to be? How much will talent cost?

Will it be a timed buy or a complete buyout of rights?

Are you buying local, regional, or national rights?

Where will the spot be aired?

Is the spot simple or complex?

Will it require multiple setups?

Where will it be filmed?

How long will the spot be: 15 seconds, 30 seconds, or 60 seconds?

Budgets present an interesting dilemma. Do you find out what your budget is before speaking to production companies to get bids, or do you speak to production companies to get bids and then go to your client with the numbers and get approval? It can go either way. The “correct” approach is all based on your clients. Either way you go, prices vary, but a general rule is, “The more intricate the concept is and the faster the turnaround time, the higher the price will be.”

Production Company

Finding a good production company is critical to getting a great spot produced. You will find that there are production companies that offer the entire package of video and audio while others only offer video, which means you will have to also team with an audio studio for sound design. As you gain experience with TV spots you will work with several different companies and find that some are better than others for certain types of spots. Some can do 3D work, while others are better with live talent. Some work quickly and keep the crew small, while others are better suited for larger productions. You will get to know the people who do the best work for you.

If you’re a creative lead who is just getting your first TV gig going, however, you will need to do some research. My first recommendation is calling other creative leads to obtain recommendations on production companies. As you have moved up in the ranks, hopefully you have developed friendships with others in our industry who will be willing to help you. Give them a call and ask for their advice on production companies they’ve used in the past.

Once you do that, call the recommended company and interview them. Have a long list of questions prepared and specifically ask to see work that was already produced for TV. Ask if they have experience in filming the specific kind of spot you are producing or if they have experience with your type of client. This will help you get an idea of what you can expect from the company when they work for you. Be sure to ask for a “demo reel” that shows snippets of multiple commercials the company has created so you can get an idea of the level of quality the firm produces on multiple projects.

Once you make it past the phone calls and narrow your candidates down to two or three, you should meet with the production companies in person. When meeting with the production company, have an idea of what you want to see, or a “vision” of what the commercial should present to your target audience. The company that’s producing your commercial should be able to translate your vision into reality.

Do your homework and don’t be afraid to ask as many questions as you need to. Request a contract that outlines the scope of the project along with the start and delivery dates and milestones to expect during the actual production. Clarify exactly what you’re being charged for and why.

Once you assign the job, you can expect that you will receive a director’s treatment. The director will create a document that outlines how he plans to turn your ideas into reality. Be open to directors’ suggestions, because they are experts in bringing spots to life; just make sure they don’t lose sight of your original concept and vision. As you work through the process, you will meet the members of the team who will be producing your commercial. Most good production companies will assign you a project manager to act as a liaison between you and the production team.

Sound Design

Whether you are recording voice on camera (VOC) or you are planning to have a voice-over (VO) recorded separately, you will need to have some sound design worked up. As mentioned previously, you can either work with a production company who can handle this portion of the production or contract with a dedicated audio production company.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that you need to get another production partner involved. Typically, you will either receive a recommendation from your video production company or already have someone in mind because you may have worked with them in the past and enjoyed the experience.

If you partner with the right sound company, they will work hard to ensure that you have very little to worry about when it comes to the production. It is crucial that the sounds, voice, and music work harmoniously in the spot and don’t fight each other for attention. Sound design balances ambient sounds, sound effects, music, and voice to support the visuals and produce a spot that promotes your client and their product or service well.

As creative lead, you must have a good ear for all of the elements that will be added or adjusted in the spot. Work closely with your video and audio production companies. If things aren’t feeling right, say so. If you think some of the sounds need to be bumped up or pulled back, let them know. Be sure of yourself. Be decisive and share your opinions. The worst thing you can do is not say anything. Time is money and the more time your video and audio partners have to spend going back and forth making edits and tweaks, the more likely it is that they will go over budget and will need to adjust what they are providing or ask for more money.

The Radio Spot

Radio advertising—whether on traditional broadcast radio, Pandora, Spotify, iTunes Radio, or any other location where the medium of choice is sound rather than video—is a powerful way of reaching your target consumers. Radio spots vary in time from 15 to 30 to 60 seconds or even more. Although 30 seconds might not seem like much time, historically agencies have utilized this time block to transmit messages quite successfully. There are a few things that are relatively obvious, but they must be part of your spot to make it as effective as possible.

Mention the Product

The client, product, or service should be introduced at the top half of the spot. Some believe that it should be mentioned immediately at the beginning of the spot. Ideally, the mention should also be combined with creating or identifying a need. For example, if you are trying to get people to purchase pizza, your 30-second spot could start with, “Need dinner fast? Broadway Joe’s has just what you’re hungry for.” With this strategy, you have managed to introduce the need and the product within the first 10 seconds of the spot. The beginning of the ad always should grab the listener’s attention by offering to solve a problem. This helps the listener pay attention to the rest of the message.

Discuss Its Benefits

Now that you’ve grabbed the listener’s attention, quickly discuss the benefits that your client’s product has to offer. Focus on the main benefit or offer and keep it short. You don’t want to rush through the spot and confuse the audience. You could say, “Broadway Joe’s has been proven as a pizza leader for over 10 years. We only use the freshest ingredients to ensure that your meal will taste great.”

Offer an Enticement

After sharing why the product is great, you must offer a reason for listeners to care and entice them to act. This can be in the form of a special offer that is only available to people who hear the 30-second spot and use a code that you will provide. For example, “You can get a medium two-topping pizza for just $5.99 if you use our listener-only special code. Give us code: JoeKnowsPizza, and you’re as good as gold.” Entice the listening audience with a strong incentive and remind them that only they qualify for this special deal.

The Call To Action And Reminder

Finally, you need to close the ad with a quick call to action and reminder about the product. For example, “Call us or visit us online to place your order and get your two-topping pizza for just $5.99. We’ve got the best pizza in town! Broadway Joe’s!” By giving listeners multiple ways to contact the client and take part of the offer, you increase the chance of success. In addition, by having customers use a code that was only offered via radio, you have a great way to track the successfulness of the spot. Win-win.

Producing The Radio Spot

A well-produced radio spot can inspire the imagination and get people thinking about your client’s service or product. Without a video, the listener’s mind is free to wander. They have every opportunity to imagine any type of scenario that you provide as long as you can grab their attention, hold their interest, get them to laugh, or most importantly, get them to pay attention. You must keep in mind that people who are listening to the radio are typically doing something else at the same time whether that’s driving to work or school, sitting at the office or at home, or exercising in a gym. So, go into it knowing that they might not listen to every word. This forces you to ensure that every word they hear is succinct and impactful!

When you create your spot, you want to use a standardized format. Standardizing is very important, because you want people to know they are hearing a commercial for the same businesses even if they hear slightly altered versions.

To standardize the sound of the spots you can

Request to use a female or male voice on all spots.

Request the same music.

Spell out the kind of energy you want put into the voice (“energetic read” or “laid-back, casual read”).

Create spots with the same type of format (problem/solution, narrative, character driven).

You can familiarize people with your spots by the way you execute them. Consistency breeds familiarity. Familiarity can breed loyalty and sales—that’s what we want.

Once you’ve knocked out the basics and received client approval on your scripts it’s time to get in the studio. You will need to reach out to several sound studios to get pricing. Once you determine who you’re going with, you will need to provide them with the specifications of what type of voice and read you want. Once you’ve selected the talent and received client approval on the voice, it’s time to go. Get in studio and work with the editor and talent to produce the spot you want. Get a full range of different takes—different energy levels, different emphasis on various words, and so on. While you’re in studio recording the talent, be sure to get as many takes as possible. Once the talent is gone, they are gone. Getting them back into the studio will cost you money.

After you’ve released the talent, you will work with the editor to get the spots you’ve ideated. Then it’s off to the client for approval. In a perfect world, you won’t receive many edits from this point and you can have the spots trafficked out.

In A Nutshell

This chapter has been a very cursory overview of TV and radio production. There is much more that goes into it, but this at least gives you a snippet of information that can bolster what you know or what you may feel you were lacking. TV production can be very enjoyable and rewarding, but it can also be extremely exhausting and, in some cases, frustrating. What you get out of it is completely based on what you put into it and who you partner with to produce the work. I have had the good fortune to work with great TV production companies (Matchframe/1080, Maverick Video Productions, Sprocket Productions, 13th Floor Studios, and Cevallos Brothers Productions) and radio/sound studios (The Living Room and Harter Music). When you have the right partners, and hopefully a realistic budget to work with, you can accomplish great things.

It is imperative that you ensure that your client has a budget to produce a TV or radio spot. There is nothing worse than having a client who wants TV, but doesn’t have the money to put into it. In my own experience, I have had some great production companies reduce their prices just to get the job and the chance at future work. The problem with doing that is twofold. First, the client is still expecting a polished, well-executed TV spot that looks good and sounds good on a shoestring budget. Second, it sets a bad precedent with the client, who now gains an unrealistic expectation that any future TV spots will cost about the same.

Your account team must provide clients with realistic estimates and be willing to have difficult conversations regarding budgets. If the client wants TV or radio but can’t afford it, then try to find another way to address their marketing challenge. Maybe it’s not a TV spot. Don’t sacrifice your reputation, the reputation of your agency, or that of your production partner by allowing budgets to get so low that nobody is being profitable and you risk producing work that is inferior or doesn’t have a positive effect on your client’s business.

That said, regardless of your budget you have a job to do. Get creative and resourceful. Try to find ways to work inside of an approved budget and the timeframe provided. Be honest with the team if something can’t get done. Lead your creative team and knock out some great award-winning spots that you, your creative team, your agency, and your client will be proud of.