Chapter 10

Situational Team Leadership

Teams have become a major strategy for getting work done. We live in teams. Our organizations are made up of teams. We move from one team to another without giving it a thought. The percentage of time we spend in team settings—project teams, work groups, cross-functional teams, virtual teams, and management teams—is ever-increasing. Managers typically spend between 30 and 99 percent of their time in a meeting or team setting. In High Five: The Magic of Working Together, Ken Blanchard, Sheldon Bowles, Don Carew, and Eunice Parisi-Carew show that being effective in today’s organizations is a team game, and without collaboration and teamwork skills, a leader is unlikely to be successful.1

Why Teams?

Teams can execute better and faster than traditional hierarchies. They have the power to increase productivity and morale or destroy it. Working effectively, a team can make better decisions, solve more complex problems, and do more to enhance creativity and build skills than individuals working alone. The team is the only unit that has the flexibility and resources to respond quickly to changes that have become commonplace in today’s world.

The business environment has become more competitive, and the issues it faces are increasingly complex. As we emphasized in Chapter 4, “Empowerment Is the Key,” this challenging environment has caused organizations to realize that they can no longer depend on hierarchical structures and a few peak performers to maintain a competitive advantage. The demand is for collaboration and teamwork in all parts of the organization. Success today comes from using the collective knowledge and richness of diverse perspectives. There is a conscious movement toward teams as the strategic vehicle for getting work accomplished and moving organizations into the future.

Fast-paced work environments require teams to operate virtually around the world. These geographically dispersed teams face special challenges in building trust, developing effective communication, and managing attentiveness.2 However, with the proper leadership and technology, virtual teams are every bit as productive and rewarding as face-to-face teams.

Teams are not just nice to have. They are hard-core units of production.

It’s a fact that people’s health and well-being are directly affected by the amount of involvement they have in the workplace. Twelve thousand male Swedish workers were studied over a 14-year period. Workers who felt isolated and had little influence over their jobs were 162 percent more likely to have a fatal heart attack than were those who had greater influence in decisions at work and who worked in teams.3 Data like this—combined with the fact that teams can be far more productive than individuals functioning alone—provides a compelling argument for creating high-involvement workplaces and using teams as the central vehicle for getting work done.

Why Teams Fail

Teams are a major investment of time, money, and resources. The cost of allowing them to falter or underproduce is staggering. Even worse, a team meeting that is considered a waste of time has wide-ranging effects. The energy does not dissipate as you leave, but spills into every aspect of organizational life. If people leave a meeting feeling unheard, or if they disagree with a decision made in the team, they leave angry and frustrated. This impacts the next event. The opposite happens when meetings feel productive and empowering—the positive energy spreads.

Teams fail for a number of reasons, from lack of a clear purpose to lack of training. Following are the top ten reasons why a team fails to reach its potential. An awareness of the obstacles to optimal team performance can prepare team members and leaders to proactively address these issues.

Five Steps to High Performing Teams

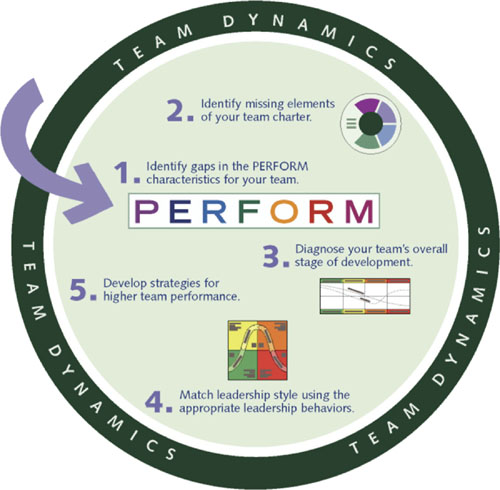

Working in a team is both an art and a science, and understanding the dynamics of teamwork has never been easy. However, after decades of research, we have identified five key processes that leaders can use to create high performing teams (see Figure 10.1):

1. Benchmark your team with PERFORM.

3. Diagnose your team’s development level.

4. Match leadership style to your team’s development level.

5. Develop strategies for higher team performance.

Figure 10.1 Team Performance Process

This five-step method for increasing team effectiveness can be adapted to any team, regardless of its purpose, pursuit, type, or size.

To help you fully understand how the models interact and become a systematic process, the following overview of each step illustrates our approach.

Step One: Benchmark Your Team with PERFORM

We define a team as two or more persons who come together for a common purpose and who are mutually accountable for results. This is the difference between a team and a group. Often, work groups are called teams without developing a common purpose and shared accountability. This can lead to disappointing results and a belief that teams do not work well. A collection of individuals working on the same task are not necessarily a team. They have the potential to become a high performing team once they clarify their purpose and values, strategies, and accountabilities.

Some teams achieve outstanding results no matter how difficult the objective. They are at the top of their class. What makes these teams different? What sets them apart and makes them capable of outperforming their peers? Although each team is unique, they all have characteristics that are shared by all outstanding teams regardless of their purpose or goals.

Building highly effective teams, like building a great organization, begins with a picture of what you are aiming for—a target. It is imperative to know what a high performing team is. That is why the Team Performance Process begins with PERFORM, an acronym that represents seven key characteristics found in all high performing teams. These represent the gold standard for teams committed to excellence. By benchmarking your team in each of these areas, you can identify the areas where you need to focus team development.

Purpose and values are the glue that holds the team together and form the foundation of a high performing team. Identifying a clear purpose is the first step in getting a team off to a good start. In high performing teams, the team is dedicated to a common purpose and shared values. Team members understand the team’s work and its importance, and strategies for achieving clear goals are agreed on.

Empowerment is what happens when the organization supports the team in doing its work effectively. An empowered team has access to business information and resources. Team members have the authority to act and make decisions with clear boundaries, and they have a clear understanding of who is accountable for what.

Relationships and communication, both internal and external, are the team’s lifeblood. Team members must respect and appreciate each other’s differences and be willing to work toward the common good rather than individual agendas. When relationships and communication are running smoothly, trust, mutual respect, and team unity are high. Team members actively listen to one another for understanding. The team uses effective methods to find common ground and manage conflict.

Flexibility is the ability to adapt to constantly changing conditions and demands, with team members backing up and supporting one another as needed. In a flexible team, roles are shared as team members work together. Team members share in team development and leadership. Team members identify and use their individual strengths. The team anticipates change and readily adapts to it.

Optimal productivity is what’s generated by a high performing team. When operating at optimal productivity, the team consistently produces significant results. Its members are committed to high standards and measures for goal accomplishment. The team uses effective problem solving and decision making to achieve goals.

Recognition and appreciation are ongoing dynamics that build and reinforce productivity and morale by focusing on progress and the accomplishment of major milestones throughout the team’s life. Everyone—including the team members, the team leader, and the larger organization—is responsible for recognition and appreciation. When recognition and appreciation flourish, the team leader and members acknowledge individual and team accomplishments. The organization values and recognizes team contributions. Finally, team members feel highly regarded within the team.

Morale is the sense of pride and satisfaction that comes from belonging to the team and accomplishing its work. High morale is essential for sustaining performance over the long term. When morale is high, team members are confident and enthusiastic about their work. Everyone feels pride and satisfaction in being a part of the team. Team members trust one another.

After reviewing the characteristics of high performing teams through the PERFORM model, most people’s reaction is “Duh.” If a team really had those characteristics, you’d better believe it would be effective.

For example, Ken was invited to a Boston Celtics practice during the heyday of Larry Bird, Robert Parish, and Kevin McHale. Standing on the sidelines with Coach KC Jones, Ken asked, “How do you lead a group of superstars like this?” KC smiled and said, “I throw the ball out and every once in a while shout ‘Shoot!’” In observing Jones as a leader, Ken noticed he didn’t follow any of the stereotypes of a strong leader. During time-outs, the players talked more than KC did. He didn’t run up and down the sidelines yelling things at the players during the game; most of the coaching was done by the team members. They encouraged, supported, and directed each other.

This team really knew how to PERFORM. Everyone knew the team’s purpose and values. They were empowered to get the job done. They had great relationships and communicated well with each other. They were flexible and changed plans as the need arose. They certainly got optimum performance. Recognition and support for each other was a way of life, and high morale was evident to everyone who watched them play.

When this low-key leader, KC Jones, retired, all the players essentially said he was the best coach they’d ever had. Why? Because he permitted everyone to lead, and that’s what a team is all about.

Don Carew observed an extraordinary example of team leadership while working with Caterpillar’s Track Type Tractors (TTT) division in Illinois.4 The TTT division was in deep trouble. The lowest-performing division of the company, it was losing millions of dollars a year and had been involved in a bitter strike. The Blanchard team worked with TTT to implement a new set of values and behaviors based on trust, mutual respect, teamwork, empowerment, risk taking, and a sense of urgency. In less than three years, the company realized a $250 million turnaround. Quality as measured by customers improved by 16 times. Employee satisfaction moved from being the lowest in Caterpillar to being the highest. All of this was achieved by people at all levels working together in teams and by the organization creating the conditions that supported teamwork, mutual respect, and trust.

Step Two: Create a Team Charter

Knowing where you are headed is the first step on the journey to high team performance. But just calling together a team and giving it a clear charge does not mean the team will become high performing. As we’ve said, team leadership is much more complicated than one-on-one leadership. Yet managers typically spend more time preparing for a meeting with one of their people than they do with their team. Often people just don’t get it: Managing a high performing team takes considerable effort. One of the single most important things a team leader can do is set up the environment for and support the team in creating a team charter.

To create a solid foundation for the team’s work, it’s important to complete a team charter at this early point in the team’s life cycle. A charter is a set of agreements that clearly states what the team is to accomplish, why it is important, and how the team will work together to achieve results. The charter documents common agreements, but it is also a dynamic document that can be modified as team needs change. Figure 10.2 shows a model for developing a charter.

The team charter agreements directly link the team’s purpose to the organizational vision and purpose. Team values and norms should reflect the organization’s values, as well as provide guidelines for appropriate behavior within the team. Identifying team initiatives sets the foundation for determining goals and roles. This is when the team establishes strategies for communication, decision making, and accountability. If the team will need resources, they are identified at this time. Once completed, the charter provides a touchstone for making sure the team is on track. The team is now ready to move from planning to doing, and it will keep the charter visible and available to navigate the stages ahead.

Step Three: Diagnose Your Team’s Development Level

Building a high performing team is a journey—a predictable progression from a collection of individuals to a well-oiled system where all the PERFORM characteristics are evident.

All teams are unique and complex living systems. The whole of a team is different from the sum of its members. Knowing the characteristics and needs of a high performing team is critical. It gives you a target to shoot for. Obviously, teams don’t start with all the PERFORM characteristics in place. Research over the past sixty years has consistently demonstrated that regardless of their purpose, teams, like individuals, go through a series of developmental stages as they grow.

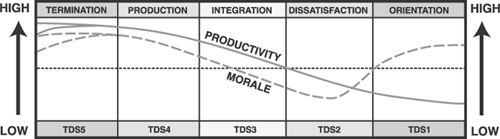

All these comprehensive research efforts were surprisingly consistent in their conclusions.5 They all identified either four or five stages of development and were very similar in their descriptions of the characteristics of each stage. After a comprehensive review of more than 200 studies on group development, Lacoursiere identified five stages of team development (see Figure 10.3), which we will examine in detail in a moment:

1. Orientation

3. Integration

4. Production

5. Termination

Figure 10.3 The Stages of Team Development Model6

Understanding these development stages and a team’s characteristics and needs at each stage is essential for team leaders and team members if they will be effective in building successful, productive teams.

That’s what diagnosis is all about. The ability to determine a team’s stage of development and assess its needs requires stepping back and looking at the team as a whole, rather than focusing on individual behaviors and needs.

Productivity and Morale

Two variables determine the team development stage: productivity and morale.

Productivity is the amount and quality of the work accomplished in relation to the team’s purpose and goals. Productivity is dependent on members’ ability to collaborate, their knowledge and skills, clear goals, and access to needed resources. Morale is the sense of pride and satisfaction that comes from belonging to the team and accomplishing its work.

Productivity often starts out low. When a group first comes together, they can’t accomplish very much. They don’t even know each other. Over time, as they learn to work together, their performance should gradually increase. If that is not the case, something is seriously wrong. Either they have a leadership problem, or the skills necessary to perform well are not present in the group.

Morale, on the other hand, starts out high and takes a sudden dip. People are usually enthusiastic about being on a new team, unless they’ve been forced to join. The initial euphoria dissipates quickly when the reality of the difficulty of working on a team comes into play. Now you might hear people say, “Why did I agree to be on that team?” As differences are explored and people begin to break through initial frustrations and working together becomes easier, the team begins to achieve results, and morale begins to rise again. Ultimately, both morale and productivity are high as a group becomes a high performing team.

Why are high morale and high productivity the ultimate goals? High morale with no performance is a party, not a team. On the other hand, a team that is achieving good results yet has low morale will eventually stumble, and its performance will fade. The bottom line is that both productivity and morale are required to produce a high performing team with sustainable results.

Diagnosing the level of productivity and morale is a clear way to determine a team’s development stage and understand team needs at any point in time.

Team Development Stage 1 (TDS1): Orientation

Most team members, unless coerced, are fairly eager to be on the team. However, they often come with high, unrealistic expectations. These expectations are accompanied by some anxiety about how they will fit in, how much they can trust others, and what demands will be placed on them. Team members are also unclear about norms, roles, goals, and timelines.

In this stage, team members depend strongly on the leader for purpose and direction. Some testing of boundaries occurs, and the central leader’s behavior is usually tentative and polite. Morale is moderately high and productivity is low during this stage.

Two of us were asked to serve on a project team to study and modify the compensation system for our consulting partners. At the first meeting, we were excited and eager to see who else was a part of the project team. Many complaints about the system had been registered, and we were eager to make positive changes. We were apprehensive about whether “they” would really listen. We also wondered how much time this would take, who would be in charge of the team, and how we would fit in with the other members. We had no idea how to proceed or even what our goals should be. We looked to the team leader to steer us in the right direction. These feelings of excitement, anxiety, and dependence on the leader are normal for team members at Stage 1.

The challenge at the orientation stage is to get the team off to a good start by developing purpose and structure for the team, as well as building relationships and trust.

The duration of this stage depends on the clarity and difficulty of the task, as well as clarity about how the team will work together. With simple, easily defined tasks, the orientation stage may be relatively short—5 to 10 percent of the team’s life. On the other hand, with complex goals and tasks, the team may spend 30 to 60 percent of its time in this stage.

Team Development Stage 2 (TDS2): Dissatisfaction

As the team gets some experience under its belt, morale dips as team members experience a discrepancy between their initial expectations and reality. Reluctant team members start out in Stage 2. The difficulties in accomplishing the task and in working together lead to confusion and frustration, as well as a growing dissatisfaction with dependence on the leader. Negative reactions to each other develop, and subgroups form that can polarize the team. The breakdown of communication and the inability to solve problems result in lowered trust. Productivity increases somewhat but may be hampered by low morale.

Back to that compensation project team we just mentioned: While we started off with enthusiasm, we quickly realized how much hard work would be involved, the goal’s controversial nature, and the possibility that recommendations we would make might not be accepted. We began to experience some strong negative feelings among members, and subgroups began to form. Frustration with the team leader began to develop. We started to wonder whether this was worth our time. These feelings of questioning, doubt, and frustration are typical of team members during Stage 2.

The challenge in the dissatisfaction stage is helping the team manage issues of power, control, and conflict and to begin to work together effectively.

The amount of time spent in this stage depends on how quickly issues can be resolved. It is possible for the team to get stuck at the dissatisfaction stage and to continue being both demoralized and relatively unproductive.

Team Development Stage 3 (TDS3): Integration

Moderate to high productivity and variable or improving morale characterize a team at the integration stage. As issues encountered in the dissatisfaction stage are addressed and resolved, morale begins to rise. The team develops practices that allow members to work together more easily. Task accomplishment and technical skills increase, which contributes to positive feelings. Increased clarity and commitment to purpose, values, norms, roles, and goals occur. Trust and cohesion grow as communication becomes more open and task-oriented. Team members are willing to share leadership and control.

Team members learn to appreciate the differences among themselves. The team starts thinking in terms of “we” rather than “I.” Because the newly developed feelings of trust and cohesion are fragile, team members tend to avoid conflict for fear of losing the positive climate. This reluctance to deal with conflict can slow progress and lead to less effective decisions.

Back to our project team: As we began resolving the frustrations we experienced in Stage 2, we began listening more carefully and came to appreciate different points of view. We developed some initial strategies for accomplishing our team purpose and clarified our goal and roles. In spite of the difficulty of achieving our goal, working with the team now became more fun. People were getting along, and at every meeting we were more clearly seeing what needed to be done. We even began to see the possibility of some success down the road. These feelings of increasing satisfaction and commitment and the development of skills and practices to make working together easier are typical of Stage 3.

Learning to share leadership and getting past the tendency to agree in order to avoid conflict are the challenges at the integration stage.

The integration stage can be quite short, depending on the ease of resolving feelings of dissatisfaction and integrating new skills. If members prolong conflict avoidance, there is a possibility that the team could return to the dissatisfaction stage.

Team Development Stage 4 (TDS4): Production

At this stage, both productivity and morale are high and reinforce one another. This is PERFORM in action. There is a sense of pride and excitement in being part of a high performing team. The primary focus is on performance. Purpose, roles, and goals are clear. Standards are high, and team members are committed not only to meeting standards, but also to continuous improvement. Team members are confident in their ability to perform and overcome obstacles. They are proud of their work and enjoy working together. Communication is open, and leadership is shared. Mutual respect and trust are the norm. The team is flexible and handles new challenges as it continues to grow.

Our project team really started to hum, and the completion of the job became a reality in our minds after many meetings and a careful study of alternatives. It finally began to feel as if the effort was worth it, and we were optimistic that the outcomes would be positive for both the company and the consulting partners. We all shared the responsibility for team leadership. We felt this had become a really great team to be on, and we were proud to be part of it. These feelings of accomplishment, pride, confidence, and a sense of unity are typical of teams who have reached Stage 4.

The challenge in the production stage is sustaining the team’s performance through new challenges and continued growth. This stage is likely to continue—with moderate fluctuations in feelings of satisfaction—throughout the team’s life.

Team Development Stage 5 (TDS5): Termination

With ongoing teams, this stage is more often a “mini termination” at different points, such as when a goal is achieved or a milestone is reached. Termination occurs in any team that is time-limited, such as project teams, ad hoc teams, or temporary task forces, so team members need to be prepared for its outcomes. Productivity and morale may increase or decrease as the end of the experience draws near. Team members feel sadness or loss—or, on the other hand, a rush to meet deadlines.

After presenting the findings of our project team, we realized we had some regrets that it was all over. We had shared some tension-filled times and had developed a real appreciation for each other, as well as a sense of bonding. This great group of people we had been meeting with for the last several months would probably never be together in the same way again. So, although we felt proud of what we had accomplished, we also felt a sense of loss as it was coming to an end. The praise and acknowledgment from the company and the consulting partners helped.

The challenge at the termination stage is to maintain necessary productivity and morale while managing closure, recognition, and celebration. This stage may vary in duration from a small part of the last meeting to a significant portion of the last several meetings, depending on the length and quality of the team experience.

* * *

While the five stages are described as separate and distinct, they share considerable overlap. Some elements of each stage can be found in every other stage. For example, just because a team is getting started (orientation stage) and needs to focus on developing a clear purpose and building a strong team charter doesn’t mean that it won’t need to revisit and refine the charter in Stage 2 or 3. The team’s dominant characteristics and needs, however, determine its development stage at any given time. A change in these characteristics and needs signals a change in the team’s development level.

Why is understanding your team’s stage of development and corresponding needs such an important step in the process? Because it allows team leaders or members to accomplish the next key step: providing leadership that responds to those needs.

Step Four: Match Leadership Style to Your Team’s Development Level

As it moves through the different development stages, a team requires leadership that is responsive to its needs at each stage. Situational Leadership® II, used extensively to develop individual performance, works equally well when applied to a team or collaborative group.

As we discussed in Chapter 5, Situational Leadership® II consists of two variables—directing behavior and supporting behavior, which combine to form four leadership styles. This same framework applies to leading teams.

Directing behavior structures and guides team outcomes. Behaviors that provide direction include organizing, structuring, educating, and focusing the team. For example, when you first join the team, you want to know how it will be organized. What do you need to learn to be a good team member? Where will the team focus its efforts? What’s the structure? Does anybody report to anybody? Who does what? When? And how?

Supporting behavior develops mutual trust and respect within the team. Behaviors that provide support include involving, encouraging, listening to, and collaborating with team members. For example, in developing team harmony and cohesion, people want to be involved in decision making, encouraged to participate, acknowledged and praised for their efforts, valued for their differences, and able to share leadership when appropriate.

Without team leadership training, people who are called to lead a team are usually clueless about what to do. They often operate on instinct. For example, suppose an inexperienced team leader thinks that the only way to lead a team is to use a participative leadership style. From Day 1, she asks everybody for suggestions about how the team should operate. The team members think the leader should answer that question. “After all,” they say, “she’s the one who called the meeting.” They begin to question why they joined this team. The leader, getting little response from her team, gets frustrated and wonders why she agreed to lead the team in the first place. Everyone is confused.

Without understanding the framework of team stages of development, it is only by chance that a leader’s behavior matches the team’s needs. Combining the Stages of Team Development Model with the Situational Leadership® II Model will help everything begin to make sense (see Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Situational Leadership® II Team Leadership Styles

The directing and supporting behaviors of the Situational Leadership® II model provide a framework for meeting team needs. They can be used by any member of the team.

Match Leadership Style to Team Development Stage

When we combine the four leadership styles with the first four stages of team development, as illustrated in Figure 10.5, we have a framework for matching each stage with an appropriate leadership style.

Figure 10.5 Situational Leadership® II: Matching Leadership Style to the First Four Team Development Stages

For team leaders and members to determine the appropriate leadership style, first diagnose the team’s stage of development in relation to its goal, considering both productivity and morale. Then locate the team’s present stage of development on the Stages of Team Development Model, and follow a vertical line up to the curve on the Situational Leadership® II Model. The point of intersection indicates the appropriate leadership style for the team.

Intervening with the appropriate leadership style at each stage will help the team progress to or maintain high performance. Matching leadership style to stages of team development, similar to partnering for performance with individuals, works best when the team leader(s) and members all know the Team Performance Process and are doing the diagnosis together.

At Stage 1, the orientation stage, a directing style is appropriate. The team is moderately eager but dependent on authority. Leaders need to get the team off to a good start by developing purpose and structure while building relationships and trust. This is the time to create a team charter and link the team’s work to the organization’s purpose and goals. Team leaders should assess training and resource needs and orient team members to one another.

At the beginning of any team, people are relatively eager to be there, and they have high expectations. Morale is high, but productivity is low due to a lack of knowledge about the task and each other. The team members need some support, but this need is much less than their need for goal- and purpose-oriented behavior. People need to clearly understand what kind of participation is expected from them. Norms should be established around communication and accountability. There should be consensus on structure and boundaries: what work will get done and by whom, what the timelines are, what tasks are to be completed, and what skills are needed to complete them.

At Stage 2, the dissatisfaction stage, a coaching leadership style is appropriate. At this point the team is probably experiencing confusion and frustration and needs to learn how to manage conflict and work together more effectively. Now is when the leader should reconfirm or clarify the team’s purpose, norms, goals, and roles; develop both task and team skills; confront difficult issues; and recognize helpful behaviors and small accomplishments.

The dissatisfaction stage is characterized by a gradual increase in task performance and a decrease in morale. Anger, frustration, confusion, and discouragement can arise due to the discrepancy between initial expectations and reality.

The dissatisfaction stage calls for continued high direction and an increase in support. Team members need encouragement and reassurance as well as skill development and strategies for working together and task achievement. At this stage, it is important to clarify the big picture and reconfirm the team’s purpose, values, and goals. It is also important to give the team more input into decision making. Recognizing team members’ accomplishments and giving feedback on progress reassures people, encourages progress, and boosts morale. This is a good time to encourage active listening and reaffirm that the team values differences of opinion. It is also helpful at this stage to have open and honest discussions about issues such as emotional blocks and coalitions, and to resolve any personality conflicts.

At Stage 3, the integration stage, a supporting leadership style is appropriate. The team, now working together more effectively but cautiously, must learn to share leadership and address conflict.

Goals and strategies are becoming clearer or have been redefined. Negative feelings are being resolved. Confidence, cohesion, and trust are increasing but still fragile. People tend to avoid conflict for fear of slipping back into the dissatisfaction of Stage 2. Team members are more willing and able to assume leadership functions.

Support and collaboration are needed in the integration stage to help team members develop confidence in their ability to work together. The team needs less direction around the task and more support focused on building confidence, cohesion, involvement, and shared leadership. This is a time to encourage people to voice different perspectives, share responsibility for leadership, and examine team functioning. Now the focus should be on increasing productivity and developing problem-solving and decision-making skills.

At Stage 4, the production stage, a delegating leadership style is appropriate. Now operating with high productivity and high morale, the team is challenged by the need to sustain its high performance.

At this stage, the team members have positive feelings about each other and their accomplishments. The quality and amount of work produced are high. Teams at this stage often need new challenges to keep morale and task focus high.

The team generally provides its own direction and support at this point and needs to be validated for that accomplishment. People are sharing leadership responsibilities, and team members are fully participating in achieving the team’s goals. Continued recognition and celebration of the team’s accomplishments are needed at this time, as well as the creation of new challenges and higher standards. Because the team is functioning at a high level, at this stage it is appropriate to foster decision-making autonomy within established boundaries.

At Stage 5, the termination stage, a supporting leadership style is appropriate. For teams with a distinct ending point, productivity can continue to increase, or it may go down because of a rush to complete the task. The approaching end of an important experience may also cause morale to increase or to drop from previous high levels.

Accepting and acknowledging the feelings that are present during this stage may be helpful. If a significant downturn in productivity and morale occurs, an increase in support, as well as some direction, is needed to maintain high performance.

Stay on the Railroad Tracks

As we talked about with one-on-one leadership, it is important in developing a team to stay on the railroad tracks—to follow the leadership style curve as the team progresses through the stages of development. After developing a team charter, a team leader can’t go to a delegating leadership style. He or she will go off the tracks, and the team may crash and burn. Building a high performing team requires a leader who can manage the journey from dependence to interdependence. When a great team leader’s job is done, team members will say, “We did it ourselves.”

Step Five: Develop Strategies for Higher Team Performance

Working in teams requires leaders to acquire new knowledge and skills that they may not have developed earlier. Yet, if they hope to build high performing teams, they’d better learn these skills. Just as in working with people one-on-one, it really helps team leaders if their people know what the leaders know. Team members need the same critical knowledge and skills as their team leader. For some people, that’s revolutionary; when they’re part of a team, they expect to be “done to.” Thinking of a team as a partnership between team leader(s) and members is foreign to many.

When you ask most team leaders after a meeting how it went, they want to talk about the number of agenda items they got through and the decisions that were made. They are focused only on content. Very seldom do they comment on or even seem to care about how the team interacted. They are “process clueless.” We have all been part of teams or groups where we dread going to meetings. Sometimes, this is driven by an egotistical leader who loves to hear his or her own voice, is not open to feedback, and wants everyone to endorse his or her agenda for everything. If you really want to find out what’s going on with teams like that, go in the halls or restrooms after a meeting, where everyone is holding “I should have said” meetings.

A conscious awareness of the dynamics occurring within a team is a critical factor in helping the team develop. Observing what is going on in the team while the team goes about its work is an important function of the team leader. This is when leaders can pick up information that will help them diagnose what the team needs to perform at the highest level. Over time, this role will be assumed by all team members.

By observing the team, leaders can develop strategies and skills to address issues confronting the team, such as conflict management, individual differences, problem solving, and decision making. For highest performance, leaders should encourage regularly scheduled team checkups to review the charter, evaluate progress, discuss changes, and incorporate lessons learned.

The Miracle of Teamwork

The Team Performance Process gives you a purposeful way to look at teamwork and provides a framework for team development that helps you stay on track. Pay attention to the dynamics. Pay attention to the mechanics. If you have trouble along the way, chances are you may not have set up something well in the beginning. Developing a team charter is probably the most underappreciated step in the process. Skipping it is a shortcut to problems.

Building and maintaining high performing teams requires two beliefs:

and

It is also essential that team members adopt community building attitudes and perspectives.

First, team members must develop a learning attitude. Everything that happens in the team is “grist for the mill.” There are no failures—only learning opportunities.

Second, the team must build a trust-based environment. Trust is built by sharing information, ideas, and skills. Building trust requires that team members cooperate rather than compete, judge, or blame. Trust is also built when team members follow through on their commitments. It is critical that team members communicate openly and honestly and demonstrate respect for others.

Third, the team must value differences. Team members should encourage and honor differences. Different viewpoints are the heart of creativity.

Fourth, people must view the team as a whole. By seeing the team as a living system rather than a collection of individuals, team members begin to think in terms of we rather than I and you.

When teams function well, miracles can happen. A thrilling and inspiring example of a high performing team is the 1980 United States Olympic hockey team.7 Twenty young men—many of whom had never played together before—came from colleges all over the country. Six months later they won the Olympic gold medal, defeating the best teams in the world—including the Soviet Union, a team that had been playing together for years. No one expected this to happen. It is considered one of the greatest upsets in sports history and is labeled a miracle. When team members were interviewed, all without exception attributed their success to teamwork. The drive, commitment, cohesiveness, cooperation, trust, team effort, and a passionate belief in a common goal—“Go for the gold”—were the reason for their success.

A leader who has attained success at the team leadership level may be ready to move on to leading the organization. After all, organizational leaders oversee a number of teams, departments, and/or divisions. The next chapter focuses on organizational leadership.