Library 3.0

Abstract

Library 3.0 is gaining popularity among research and academic library users faster than had been anticipated. In fact, it is currently deemed one of the most exciting advances in research and academic library development. The increasing popularity of Library 3.0 is attributed partly to its potential to provide an environment conducive to exploration, innovation, inspiration and personalisation. It emphasises context and not just the content of information service provision. Thus, it is anchored in a number of human factors, such as community, relationships, connection, conversation, personalisation, comfort, simplicity, play, progress and passion, which define progressiveness. Significantly, Library 3.0 is not about quick fixes but is a model which enables libraries to grow beyond being book-based and extend the information experience to wherever, however and whenever the users want it.

Keywords

3.1. Library 3.0 principles

3.1.1. The library is intelligent

3.1.2. The library is organised

Table 3.1

Curation and aggregation tools for research and academic libraries

| Tool | Potential use |

| Yahoo Pipes | to mash up different online data sources into one, then sorting and filtering it to meet library users’ information needs. Users do not have to visit each online data source independently, but get the aggregate of the content of the sites of interest. Yahoo Pipes can also enable library users to transform and enrich the content of their favourite online sources to yield customised and highly usable information resource. |

| CIThread | stands for Collective Intelligence Threading. Enables library users to identify, collect, organise and use valuable content from online sources. The library user indicates interest by specifying a set of key words that the application uses to identify relevant web content. An important feature of CIThread is its capacity to develop patterns of content use, which it then applies to refine and enrich searches. CIThread users are also able to publish their findings on other social media outlets. |

| Curata | This is a content curation engine which enables library users to search, organise and share online resources. One of Curata’s important features is a self-learning system which enables it to learn what library users like or dislike over time and automate the content curation process with little or no direct intervention from users. Curata constantly searches the web to discover fresh content as soon as it is posted. |

| CurationStation | This tool enables library users to set up automated searches, which scour all web content formats and types for specified content. The findings are presented together as a feed or any other content format the user prefers. Curation Station also enables users to share the curated content. |

| CurationSoft | This is desktop-based curation software enabling library users to curate content from various online sources and share it as blog posts. Library users can drag and drop CurationSoft content into any HTML editor. This makes it flexible and usable on many web platforms. |

| DayLife | Library users can use DayLife to discover, collect and share media articles and other products. It is hosted in the cloud, making it cost-effective and easy to set up and use. |

| Eqentia | This is a content curation software library users can use to mine, filter and share atomised and scattered topical content from social media platforms in real time. |

| OneSpot | Library users can use OneSpot to discover, use and share most popular content on topics or for communities of interest to them. |

| Scoop.it | This is a news curation tool which library users can find valuable in discovering new information, adding their own perspectives and sharing it in their communities in a newspaper format. |

| Storify | This is a social network service that enables library users to collect content from various sources in cyberspace, contextualise and publish it in a timeline or horizontal slide show. These timelines or shows can be searched by other library users with similar interests and embedded in other online information channels. |

| List.ly | This is a collaborative platform for creating lists. Library users can start a list on any of a wide array of topics, to which other users can add. Originators of lists in List.ly can moderate the posts of others to ensure credibility or suitability of content. Lists thus created can be shared or embedded in other information outlets in cyberspace. Regardless of where they are published, List.ly lists continue growing as users add new content. |

| Newsle | Library users may use Newsle to keep track of stories in cyberspace on their colleagues, friends or community members. This enables the library users to keep track of what people of interest to them publish, or what is published about them. They then have an opportunity to read the published stories. Users can also share the information through popular social media platforms such as Facebook or Twitter; and can rate the content on a scale. |

| Bundlepost | Social media content management system which library users and librarians can use to manage their social media content automatically. Bundlepost also enables users to warehouse all their social media content in one place, making it easy to search. |

| Triberr | This is a blog amplification platform that library users and librarians can utilise to build and support groups, known as tribes, by sharing or recommending information and links from blogs through Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. Each member of the tribe, based on common interests, shares their latest blog posts, which other members amplify by sharing them through their own networks. |

| This is a digital content-sharing platform which library users can utilise to share information by pinning images, videos and objects on their boards (like walls in Facebook). Library users and librarians can use Pinterest to share information resources or events. Users can re-pin images from other users’ pin-boards and sharing the information further. | |

| ContentGems | Formerly known as Intigi, ContentGems is a content curation platform through which library users can obtain aggregated content based on specified interests. The content thus accessed can be shared further through RSS feeds, blogs, Twitter and other social media outlets. Library users and librarians can also use the plan to connect to other people with whom they share common interests. |

| Feedly | This is a personalised news aggregator that collects news from a variety of online sources selected by the user. The user is able to customise and share the aggregated news as they wish. Library users and librarians can use Feedly to aggregate and share news items relating to library services and products. Library newsletters and other online publications can be circulated effectively through Feedly. |

| Dizkover | This is a social content discovery platform that enables members to discover popular and interesting items, as voted by other members. The credibility of the votes of members is achieved through a filtering system based on the members’ reputations. The content is organised in channels, which are created or contributed to by the members. Library users can use Dizkover to identify the trending issues in their areas of interest. Researchers, for instance, can use the platform to understand popular research topics and trends. They can also use it to identify credible research information based on the votes of users, preferably in appropriate research channels. Librarians can also use Dizkover to discover the information interests of the library users, based on the votes of the targeted members. They can also use the platform to identify experts on specific issues, based on their Dizkover reputations. These experts can then be engaged as apomediaries or reviewers of relevant information resources and services. |

| Aggregage | This is an automatic content curator, which aggregates information from online sources such as blogs, social media networks, discussion forums and other user-recommended sources. The content is curated based on user preferences, as demonstrated by their usage. Aggregage content is published as specialised topical web sites or online newsletters. Librarians can use Aggregage to curate and disseminate library publications on relevant issues and topics. The librarians can also use the curated content as the nuclei of specialised user communities that can enhance the reach and usability of library services and products. |

| Kweeper | Kweeper is a personalised online library which users utilise to collect and share content such as music, videos, news and other issues of interest. Library users can use the platform to build a personalised digital library that can be used to share with other users in their networks. Similarly, librarians can develop content that can be curated and shared by users on Kweeper. These Kweeper outlets can serve as mini-libraries to extend the reach of specific library services and products. Kweeper can also be used as a channel to market library services and products. It can also be used by librarians to identify the services and products most liked by the users. This information can be used as the basis of important decisions governing the design, development and deployment of library services and products. |

| Flipboard is a platform through which users can create online magazines whose content is curated from various digital sources. The content encompasses anything of interest to the curator. The magazines created through Flipboard can be shared by users with their followers. Librarians can use Flipboard to publish and distribute newsletters cost-effectively. Similarly, library users can utilise Flipboard to curate information of interest from innumerable sources easily. Thus, Flipboard can facilitate the collection and sharing of information on topical issues by library users and librarians. | |

| Zeef | This is a curated and ranked web collection of information created, collected or filtered by experts. The content is organised into subjects by experts who have a deep passion for the issues. Library users and librarians can act as subject experts and contribute or filter content that can be used by other information seekers. They can similarly benefit from content filtered by other experts on subjects of interest to them. In an environment of information overload, Zeef takes the burden of evaluating the credibility of content from the users to committed experts. This increases the speed of credible information searching, retrieval and use. |

| Meddle | This is a content marketing tool enabling the users to add comments on information items of interest. The annotated information resources can then be shared by the commentator through social networking media such as Twitter and blogs. Library users, as experts in the areas of interest, can identify and add value to useful information resources through Meddle. They can also share the enriched information resources with other users in their social networks who may also add their own comments on the resources, further enriching them. Librarians can also point users to credible information by adding relevant comments on the resources. |

| BlogBridge | This is a feeds aggregator which enables its users to discover, organise and read RSS feeds of interest to them. It is useful for persons who have subscribed to multiple RSS feeds and who may find it difficult to filter the content. Library users can utilise BlogBridge to discover valuable content without having to use tedious and less productive search techniques and tools. |

| Trapit | This is a curation application that enables its users to discover, engage with and share relevant content on the web. Trapit’s stated mission is to ‘raise the signal and lower the noise’ through contextual analysis of user preferences. Trapit maintains a vast library of vetted online content sources, which users can retrieve or add to. Trapit users can share the content they glean from the library through myriad communication channels and devices. Research and academic libraries can create Trapit accounts which they can use to select, trap and share credible content with their users. |

3.1.3. The library is a federated network of information pathways

3.1.4. The library is apomediated

Table 3.2

Comparison between modes of mediation in libraries

| Attribute | Type of mediation | ||

| Intermediation | Disintermediation | Apomediation | |

| Philosophy | Standing between | Standing aloof | Standing by |

| Power (control) | Mediator | None | All participants |

| Guidance | Mediator | Crowd | Self |

| Mode of learning | Transfer (rich to reach) | Imitation | Diffusion |

| Quantity of knowledge | Scarcity | Overload | Abundance |

| Relationship | Hierarchical | Casual | Ambient intimacy |

| Mode of operation | Match-making | Creative chaos | Serendipity |

| Partnership | Cooperation | Coexistence | Collaboration |

| Type of knowledge | Impersonal | General | Personal (original) |

| Flexibility | Rigid | Chaotic | Flexible |

| Redundancy | Centralised | Decentralised | Distributed |

| Safety | Fear (of authority) | Uncharted | Trust |

| Costs | High | Medium | Low |

| Time for learning | Long | Medium | Short |

| Transparency | Low | Medium | High |

| Direction of learning | Upstream | Midstream | Downstream |

| Applicability | Prescriptive | Speculative | Experiential |

3.1.5. The library is ‘my library’

3.2. Comparing Library 3.0 with the other library service models

3.2.1. Library 0.0 and Library 3.0

3.2.2. Library 1.0 and Library 3.0

3.2.3. Library 2.0 and Library 3.0

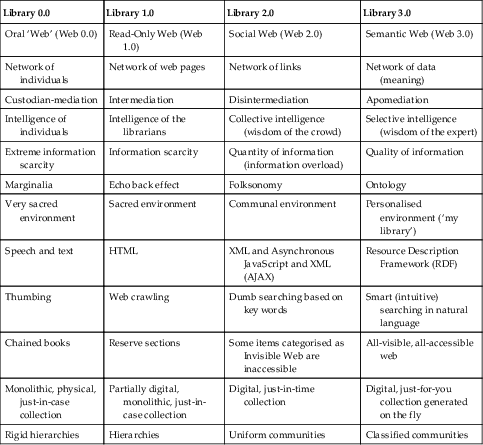

Table 3.3

Comparison of library service models

| Library 0.0 | Library 1.0 | Library 2.0 | Library 3.0 |

| Oral ‘Web’ (Web 0.0) | Read-Only Web (Web 1.0) | Social Web (Web 2.0) | Semantic Web (Web 3.0) |

| Network of individuals | Network of web pages | Network of links | Network of data (meaning) |

| Custodian-mediation | Intermediation | Disintermediation | Apomediation |

| Intelligence of individuals | Intelligence of the librarians | Collective intelligence (wisdom of the crowd) | Selective intelligence (wisdom of the expert) |

| Extreme information scarcity | Information scarcity | Quantity of information (information overload) | Quality of information |

| Marginalia | Echo back effect | Folksonomy | Ontology |

| Very sacred environment | Sacred environment | Communal environment | Personalised environment (‘my library’) |

| Speech and text | HTML | XML and Asynchronous JavaScript and XML (AJAX) | Resource Description Framework (RDF) |

| Thumbing | Web crawling | Dumb searching based on key words | Smart (intuitive) searching in natural language |

| Chained books | Reserve sections | Some items categorised as Invisible Web are inaccessible | All-visible, all-accessible web |

| Monolithic, physical, just-in-case collection | Partially digital, monolithic, just-in-case collection | Digital, just-in-time collection | Digital, just-for-you collection generated on the fly |

| Rigid hierarchies | Hierarchies | Uniform communities | Classified communities |