Library 3.0 librarianship

Abstract

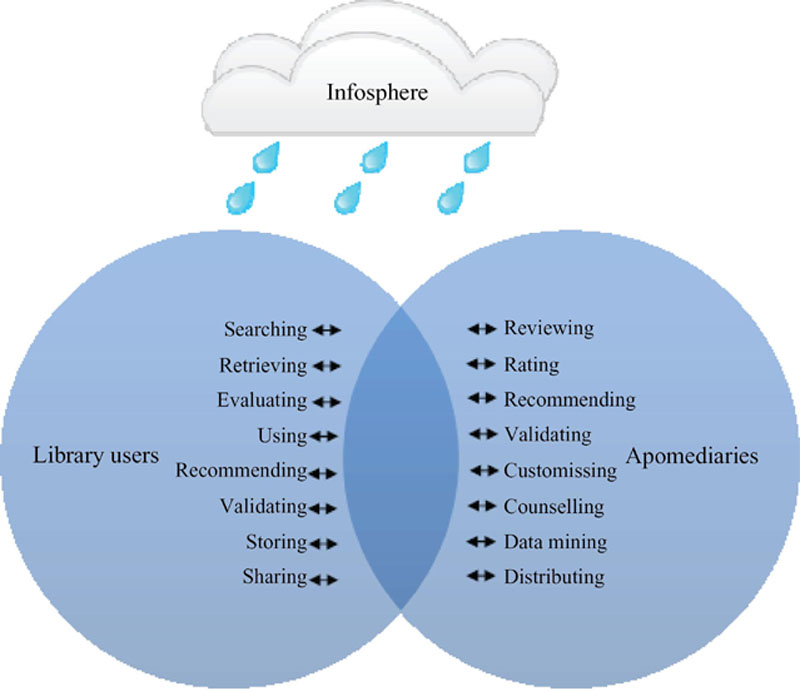

A true Library 3.0 environment can be realised only if all the stakeholders recognise and play their roles in creating a facilitative information ecosystem. Unfortunately, the focus of the discussions on Library 3.0 is currently largely on the roles played and skills required by librarians to deploy this model. Little, if anything, is said about the roles and skills library users need at their disposal to participate effectively in apomediated Library 3.0 settings. The reality is that Library 3.0 creates a new demand for increased cooperation and collaboration between librarians and users. Each of these parties must understand their roles, obligations and privileges. They must also accept that some of the roles they used to play may have changed or must change in the new information ecosystem. Therefore, they must learn what frontiers to defend and which to give up. All stakeholders must be engaged in creating the information environment which they desire. This process requires particular competencies, attitudes and behaviour which all must be willing and able to develop and nurture.

Keywords

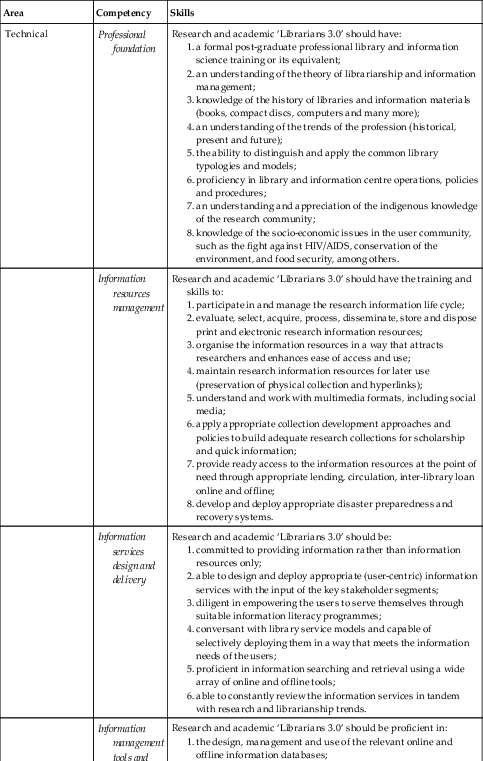

4.1. Core competencies of ‘Librarian 3.0’

4.1.1. Technical professional skills

4.1.2. Personal and interpersonal skills

4.1.3. Information and communication technology (ICT) skills

4.1.4. Management skills

4.1.5. Research skills

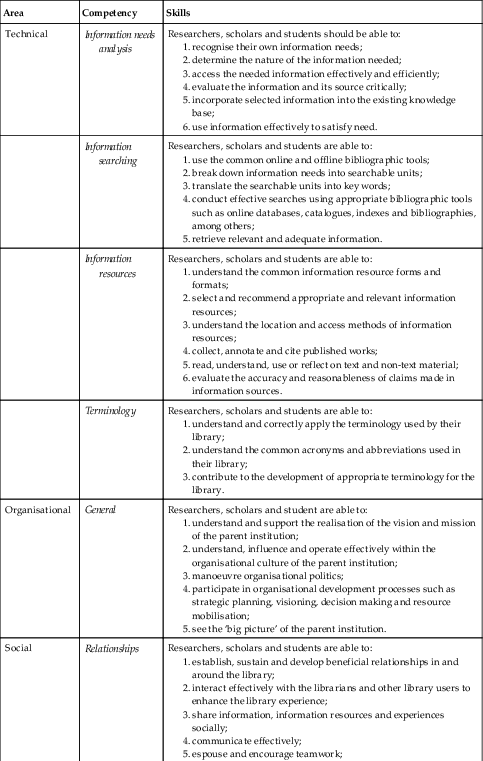

Table 4.1

Competency index of research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’

| Area | Competency | Skills |

| Technical | Professional foundation | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should have: 1. a formal post-graduate professional library and information science training or its equivalent;

2. an understanding of the theory of librarianship and information management;

3. knowledge of the history of libraries and information materials (books, compact discs, computers and many more);

4. an understanding of the trends of the profession (historical, present and future);

5. the ability to distinguish and apply the common library typologies and models;

6. proficiency in library and information centre operations, policies and procedures;

7. an understanding and appreciation of the indigenous knowledge of the research community;

8. knowledge of the socio-economic issues in the user community, such as the fight against HIV/AIDS, conservation of the environment, and food security, among others.

|

| Information resources management | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should have the training and skills to: 1. participate in and manage the research information life cycle;

2. evaluate, select, acquire, process, disseminate, store and dispose print and electronic research information resources;

3. organise the information resources in a way that attracts researchers and enhances ease of access and use;

4. maintain research information resources for later use (preservation of physical collection and hyperlinks);

5. understand and work with multimedia formats, including social media;

6. apply appropriate collection development approaches and policies to build adequate research collections for scholarship and quick information;

7. provide ready access to the information resources at the point of need through appropriate lending, circulation, inter-library loan online and offline;

8. develop and deploy appropriate disaster preparedness and recovery systems.

| |

| Information services design and delivery | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should be: 1. committed to providing information rather than information resources only;

2. able to design and deploy appropriate (user-centric) information services with the input of the key stakeholder segments;

3. diligent in empowering the users to serve themselves through suitable information literacy programmes;

4. conversant with library service models and capable of selectively deploying them in a way that meets the information needs of the users;

5. proficient in information searching and retrieval using a wide array of online and offline tools;

6. able to constantly review the information services in tandem with research and librarianship trends.

| |

| Information management tools and techniques | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should be proficient in: 1. the design, management and use of the relevant online and offline information databases;

2. indexing, classification, cataloguing and abstracting schemes and tools;

3. social media information-management tools and concepts including tagging, folksonomies and social bookmarking.

| |

| Personal and interpersonal | Personal attributes and attitude | In the line of duty, research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ exhibit: 1. passion, enthusiasm, resilience, approachability, curiosity, open-mindedness, independence, diplomacy, sensitivity, flexibility, innovativeness, critical thinking and adaptability;

2. moral uprightness according to the virtue systems of the user community;

3. balanced lifestyle;

4. willingness to take calculated risks.

|

| Communication | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should possess: 1. excellent oral and written communication;

2. proficiency in the languages the user community understands best;

3. ability to present ideas effectively;

4. skills and tools to facilitate and act on users’ feedback;

5. ability to impart knowledge effectively.

| |

| Public relations | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should: 1. create an environment of mutual respect and trust around the library;

2. negotiate confidently and persuasively;

3. participate in the community activities (community relations);

4. work effectively with suppliers and vendors;

5. respect and appreciate divergent views;

6. genuinely value all users;

7. understand organisational dynamics (politics);

8. possess conflict resolution acumen;

9. market and promote library services and products.

| |

| Networking | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should have the skills to: 1. create mutually beneficial partnerships and alliances;

2. participate effectively in the relevant professional associations locally, regionally and internationally;

3. create and sustain inter-departmental linkages and partnerships, especially with the ICT department;

4. harness essential synergy in the department, organisation and beyond;

5. mobilise resources within the organisation, donors and community;

6. organise events and programmes which enhance the visibility and usability of the library (art galleries, reading nights, and many more);

7. lead and be part of a team.

| |

| Information and Communication Technology (ICT) | ICT systems | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should have the capacity to: 1. develop ICT access and usage policies;

2. build the capacity of users, especially older users, in the use of the relevant ICT tools and systems;

3. evaluate, select, acquire, configure and maintain basic ICT systems relevant to the library;

4. install, update and monitor basic ICT security systems including antivirus utilities and firewalls;

5. administer Intranets, web servers and basic local area network (LAN) systems;

6. work with open-source tools and systems.

|

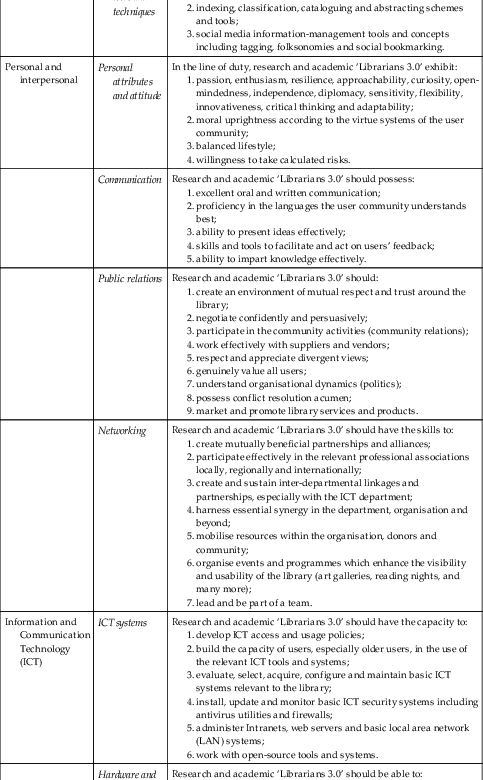

| Hardware and software | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should be able to: 1. configure and troubleshoot basic ICT hardware such as computers, printers, scanners, digital cameras, external hard discs and photocopiers, among other items of equipment;

2. install and configure basic operating systems, applications and databases.

| |

| Internet | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should have the capacity to: 1. install, configure and monitor an Internet connection through wireless, cabled and USB equipment;

2. perform advanced information searches on the Internet using search engines and information gateways, among other tools.

| |

| Web publishing | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ are: 1. proficient with web content-management systems, especially open-source systems such as Joomla, Drupal and others;

2. conversant with web content development tools such as Dreamweaver, among others;

3. able to script and edit basic HTML and XML codes;

4. comfortable with common FTP packages to manage web site files;

5. conversant with web animation packages such as Flash;

6. able to post and update content on social media tools such as Twitter, Flickr, blogs, MySpace, Facebook, SlideShare, wikis and RSS;

7. able to promote an online publication effectively using search engines, online directories and other systems.

| |

| Desktop publishing (DTP) | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should be able to: 1. design and publish basic posters, newsletters, briefing notes and other publications using common DTP packages such as InDesign, Adobe PageMaker and Adobe Digital Publishing Suite, among others;

2. edit and integrate photos and other graphics into publications using Adobe Photoshop, among others.

| |

| Digitisation | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ should be conversant with: 1. scanners and other optical character-recognition tools and systems;

2. digital cameras;

3. smartphones;

4. photocopiers;

5. electronic archiving tools and techniques;

6. audio and video capture, editing and publication.

| |

| Management | General management | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’: 1. understand the day-to-day administration and supervisory management of a library or information centre;

2. perceive the big picture and fits the library functions into the vision and mission of the parent organisation;

3. plan, set priorities and evaluate the performance of the library;

4. participate actively in organisational strategic planning;

5. calculate and demonstrate the return on investment in the library;

6. manage library ergonomics and physical facilities including furniture, shelves, decoration, cleaning, lighting and ventilation;

7. manage change;

8. recruit, train, mentor, inspire and retain professional and administrative staff essential for the success of the library;

9. understand organisational behaviour.

|

| Funds management | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ are able to: 1. perform basic book-keeping tasks;

2. develop and manage the library’s budgets;

3. manage the library’s grants.

| |

| Project management | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’ have the capacity to: 1. write project proposals;

2. perform day-to-day management of the library’s special projects;

3. monitor and evaluate the library’s special projects;

4. compile and disseminate project reports.

| |

| Legal affairs | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’: 1. understand and apply copyright and other intellectual property laws;

2. understand, interpret and apply freedom-of-information policies, right of access to information and other provisions in their jurisdiction.

| |

| Research | General | Research and academic ‘Librarians 3.0’: 1. possess qualitative and quantitative research skills;

2. participate in the entire research life cycle;

3. understand the research trends, literature and researchers in the institution’s area(s) of research interest;

4. conduct their own research and publish in peer-refereed journals;

5. support researchers and other users in reference and research output management.

|

Source: Adapted from Kwanya, Stilwell and Underwood (2012).

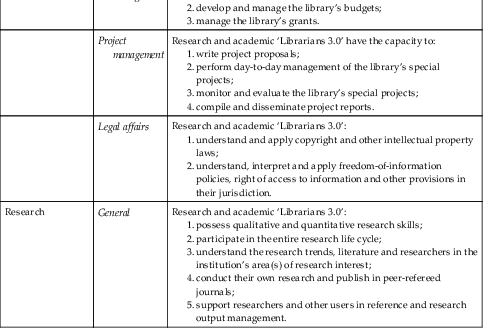

4.2. Core competencies of users in Library 3.0

4.2.1. Information competency

4.2.2. Bibliographic competency

4.2.3. Information resource competency

4.2.4. Organisational competency

4.2.5. Terminological competency

4.2.6. Technological competency

4.2.7. Social competency

4.2.8. Legal competency

4.2.9. Knowledge management competency

4.2.10. Research competency

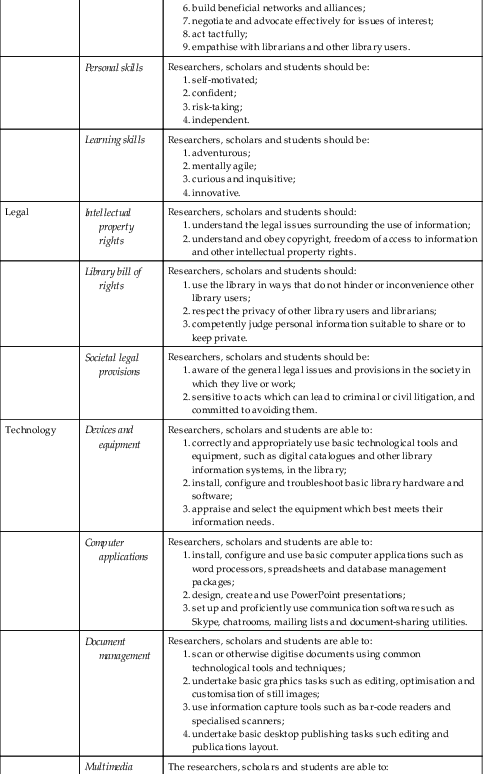

Table 4.2

Competency index of Library 3.0 users

| Area | Competency | Skills |

| Technical | Information needs analysis | Researchers, scholars and students should be able to: 1. recognise their own information needs;

2. determine the nature of the information needed;

3. access the needed information effectively and efficiently;

4. evaluate the information and its source critically;

5. incorporate selected information into the existing knowledge base;

6. use information effectively to satisfy need.

|

| Information searching | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. use the common online and offline bibliographic tools;

2. break down information needs into searchable units;

3. translate the searchable units into key words;

4. conduct effective searches using appropriate bibliographic tools such as online databases, catalogues, indexes and bibliographies, among others;

5. retrieve relevant and adequate information.

| |

| Information resources | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. understand the common information resource forms and formats;

2. select and recommend appropriate and relevant information resources;

3. understand the location and access methods of information resources;

4. collect, annotate and cite published works;

5. read, understand, use or reflect on text and non-text material;

6. evaluate the accuracy and reasonableness of claims made in information sources.

| |

| Terminology | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. understand and correctly apply the terminology used by their library;

2. understand the common acronyms and abbreviations used in their library;

3. contribute to the development of appropriate terminology for the library.

| |

| Organisational | General | Researchers, scholars and student are able to: 1. understand and support the realisation of the vision and mission of the parent institution;

2. understand, influence and operate effectively within the organisational culture of the parent institution;

3. manoeuvre organisational politics;

4. participate in organisational development processes such as strategic planning, visioning, decision making and resource mobilisation;

5. see the ‘big picture’ of the parent institution.

|

| Social | Relationships | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. establish, sustain and develop beneficial relationships in and around the library;

2. interact effectively with the librarians and other library users to enhance the library experience;

3. share information, information resources and experiences socially;

4. communicate effectively;

5. espouse and encourage teamwork;

6. build beneficial networks and alliances;

7. negotiate and advocate effectively for issues of interest;

8. act tactfully;

9. empathise with librarians and other library users.

|

| Personal skills | Researchers, scholars and students should be: 1. self-motivated;

2. confident;

3. risk-taking;

4. independent.

| |

| Learning skills | Researchers, scholars and students should be: 1. adventurous;

2. mentally agile;

3. curious and inquisitive;

4. innovative.

| |

| Legal | Intellectual property rights | Researchers, scholars and students should: 1. understand the legal issues surrounding the use of information;

2. understand and obey copyright, freedom of access to information and other intellectual property rights.

|

| Library bill of rights | Researchers, scholars and students should: 1. use the library in ways that do not hinder or inconvenience other library users;

2. respect the privacy of other library users and librarians;

3. competently judge personal information suitable to share or to keep private.

| |

| Societal legal provisions | Researchers, scholars and students should be: 1. aware of the general legal issues and provisions in the society in which they live or work;

2. sensitive to acts which can lead to criminal or civil litigation, and committed to avoiding them.

| |

| Technology | Devices and equipment | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. correctly and appropriately use basic technological tools and equipment, such as digital catalogues and other library information systems, in the library;

2. install, configure and troubleshoot basic library hardware and software;

3. appraise and select the equipment which best meets their information needs.

|

| Computer applications | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. install, configure and use basic computer applications such as word processors, spreadsheets and database management packages;

2. design, create and use PowerPoint presentations;

3. set up and proficiently use communication software such as Skype, chatrooms, mailing lists and document-sharing utilities.

| |

| Document management | Researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. scan or otherwise digitise documents using common technological tools and techniques;

2. undertake basic graphics tasks such as editing, optimisation and customisation of still images;

3. use information capture tools such as bar-code readers and specialised scanners;

4. undertake basic desktop publishing tasks such editing and publications layout.

| |

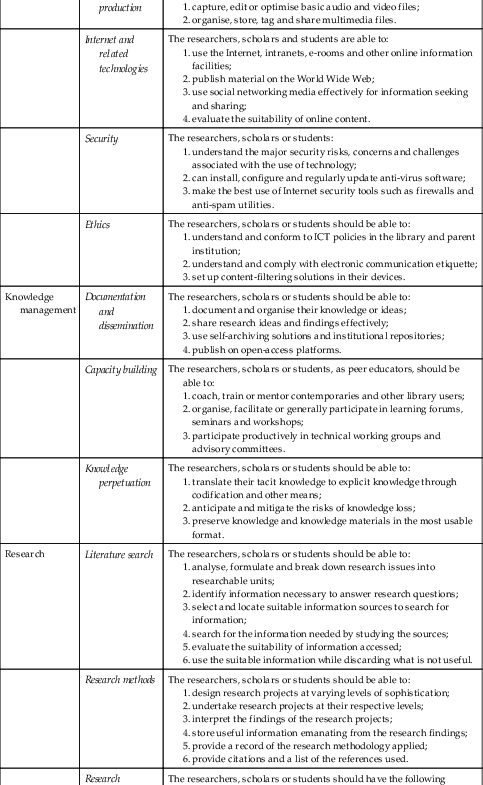

| Multimedia production | The researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. capture, edit or optimise basic audio and video files;

2. organise, store, tag and share multimedia files.

| |

| Internet and related technologies | The researchers, scholars and students are able to: 1. use the Internet, intranets, e-rooms and other online information facilities;

2. publish material on the World Wide Web;

3. use social networking media effectively for information seeking and sharing;

4. evaluate the suitability of online content.

| |

| Security | The researchers, scholars or students: 1. understand the major security risks, concerns and challenges associated with the use of technology;

2. can install, configure and regularly update anti-virus software;

3. make the best use of Internet security tools such as firewalls and anti-spam utilities.

| |

| Ethics | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. understand and conform to ICT policies in the library and parent institution;

2. understand and comply with electronic communication etiquette;

3. set up content-filtering solutions in their devices.

| |

| Knowledge management | Documentation and dissemination | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. document and organise their knowledge or ideas;

2. share research ideas and findings effectively;

3. use self-archiving solutions and institutional repositories;

4. publish on open-access platforms.

|

| Capacity building | The researchers, scholars or students, as peer educators, should be able to: 1. coach, train or mentor contemporaries and other library users;

2. organise, facilitate or generally participate in learning forums, seminars and workshops;

3. participate productively in technical working groups and advisory committees.

| |

| Knowledge perpetuation | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. translate their tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge through codification and other means;

2. anticipate and mitigate the risks of knowledge loss;

3. preserve knowledge and knowledge materials in the most usable format.

| |

| Research | Literature search | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. analyse, formulate and break down research issues into researchable units;

2. identify information necessary to answer research questions;

3. select and locate suitable information sources to search for information;

4. search for the information needed by studying the sources;

5. evaluate the suitability of information accessed;

6. use the suitable information while discarding what is not useful.

|

| Research methods | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. design research projects at varying levels of sophistication;

2. undertake research projects at their respective levels;

3. interpret the findings of the research projects;

4. store useful information emanating from the research findings;

5. provide a record of the research methodology applied;

6. provide citations and a list of the references used.

| |

| Research personality | The researchers, scholars or students should have the following personality traits which can enhance their research potential: 1. open-mindedness;

2. adaptability;

3. creativity;

4. independence of thought;

5. keenness;

6. team spirit.

| |

| Research management | The researchers, scholars or students should be able to: 1. manage research projects at all levels;

2. apply or enforce ethical considerations during research;

3. consider and manage the environmental impacts of research projects.

|

4.3. Apomediation in the Library 3.0 context

4.4. Research and academic librarians as apomediaries

4.4.1. Conducting reviews

4.4.2. Content rating and recommendation

4.4.3. Content validation

4.4.4. Content customisation

4.4.5. Information counselling

4.4.6. Knowledge discovery and data mining

4.4.7. Infodemiology and infoveillance