Managing the global pipeline

- The trend towards globalisation in the supply chain

- Gaining visibility in the global pipeline

- Financing global supply chains

- Organising for global logistics

- Thinking global, acting local

- The future of global sourcing

Global brands and companies now dominate most markets. There has been a steady trend towards the worldwide marketing of products under a common brand umbrella – whether it be Coca-Cola or Marlborough, IBM or Toyota. At the same time the global company has revised its previously localised focus, manufacturing and marketing its products in individual countries, and now instead will typically source on a worldwide basis for global production and distribution.

The logic of the global company is clear: it seeks to grow its business by extending its markets whilst at the same time seeking cost reduction through scale economies in purchasing and production and through focused manufacturing and/or assembly operations.

However, whilst the logic of globalisation is strong, we must recognise that it also presents certain challenges. Firstly, world markets are not homogeneous, there is still a requirement for local variation in many product categories. Secondly, unless there is a high level of co-ordination the complex logistics of managing global supply chains may result in higher costs and extended lead-times.

These two challenges are related: on the one hand, how to offer local markets the variety they seek whilst still gaining the advantage of standardised global production and, on the other, how to manage the links in the global chain from sources of supply through to end user. There is a danger that some global companies in their search for cost advantage may take too narrow a view of cost and only see the purchasing or manufacturing cost reduction that may be achieved through using low-cost supply sources. In reality, it is a total cost trade-off where the costs of longer supply pipelines may outweigh the production cost saving. Figure 10.1 illustrates some of the potential cost trade-offs to be considered in establishing the extent to which a global strategy for logistics will be cost-justified. Clearly a key component of the decision to go global must be the service needs of the marketplace. There is a danger that companies might run the risk of sacrificing service on the altar of cost reduction through a failure to fully understand the service needs of individual markets.

Figure 10.1 Trade-offs in global logistics

The trend towards global organisation of both manufacturing and marketing is highlighting the critical importance of logistics and supply chain management as the keys to profitability. The complexity of the logistics task appears to be increasing exponentially, influenced by such factors as the increasing range of products, shorter product life cycles, marketplace growth and the number of supply/market channels.

There is no doubting that the globalisation of industrial activity has become a major issue in business. Articles in the business press, seminars and academic symposia have all focused upon the emerging global trend. The competitive pressures and challenges that have led to this upsurge of interest have been well documented. What are less well understood are the implications of globalisation for operations management in general and in particular for logistics management.

At the outset it is important that we define the global business and recognise its distinctiveness from an international or a multinational business. A global business is one that does more than simply export. The global business will typically source its materials and components in more than one country. Similarly it will often have multiple assembly or manufacturing locations geographically dispersed. It will subsequently market its products worldwide. A classic example is provided by Nike – the US-based sportswear company. The company outsources virtually 100 per cent of its shoe production, for example, retaining in-house manufacturing in the United States of a few key components of its patented Nike Air System. Nike‘s basketball shoe, for example, is designed in the United States but manufactured in South Korea and Indonesia from over 70 components supplied by companies in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia and the United States. The finished products are sold around the world.

The trend towards globalisation and offshore sourcing has been growing rapidly for several decades. There has been a transformation from a world where most markets used to be served from local sources to one where there is a growing worldwide interdependence of suppliers, manufacturers and customers in what has truly become a ‘global village’.

Early commentators like Levitt1 saw the growth of global brands and talked in terms of the growing convergence of customer preferences that would enable standardised products to be marketed in similar fashion around the world. However, the reality of global marketing is often different, with quite substantial differences in local requirements still very much in evidence. Thus, whilst the brand may be global, the product may need certain customisation to meet specific country needs, whether it be left- or right-hand drive cars or different TV transmission standards or local tastes. A good example is Nescafé, the instant coffee made by Nestlé, which has over 200 slightly different formulations to cater for preferences in taste, country by country.

The trend towards globalisation in the supply chain

Over the last 50 years or so the growth in world trade has tended to outstrip growth in global gross domestic product (GDP). In part this trend is driven by expanding demand in new markets, but the liberalisation of international trade through World Trade Organisation (WTO) accords has also had a significant effect. A further factor driving globalisation in many industries has been the massive growth in container shipping which has led to a significant reduction in the real costs of transport.

Once, companies established factories in overseas countries to manufacture products to meet local demand. Now, with the reduction of trade barriers and the development of a global transportation infrastructure, fewer factories can produce in larger quantities to meet global, rather than local, demand.

As the barriers to global movement have come down so the sources of global competition have increased. Newly emerging economies are building their own industries with global capabilities. At the same time, technological change and production efficiencies mean that most companies in most industries are capable of producing in greater quantity at less cost. The result of all of this is that there is now overcapacity in virtually every industry, meaning that competitive pressure is greater than ever before.

To remain competitive in this new global environment, companies will have to continually seek ways in which costs can be lowered and service enhanced, meaning that supply chain efficiency and effectiveness will become ever-more critical.

In developing a global logistics strategy a number of issues arise which may require careful consideration. In particular, what degree of centralisation is appropriate in terms of management, manufacturing and distribution, and how can the needs of local markets be met at the same time as the achievement of economies of scale through standardisation?

Three of the ways in which businesses have sought to implement their global logistics strategies have been through focused factories, centralised inventories and postponement.

1 Focused factories

The idea behind the focused factory is simple: by limiting the range and mix of products manufactured in a single location the company can achieve considerable economies of scale. Typically the nationally oriented business will have ‘local-for-local’ production, meaning that each country’s factory will produce the full range of products for sale in that country. Conversely, the global business will treat the world market as one market and will rationalise its production so that the remaining factories produce fewer products in volumes capable of satisfying perhaps the entire market.

One company that has moved in this direction is Mars. Their policy has been to simultaneously rationalise production capacity by seeking to manage demand as a whole on at least at a regional level and to concentrate production by category, factory by factory. Hence their M&Ms for sale in Moscow are likely to have been produced in the United States. In a similar fashion, Heinz produce tomato ketchup for all of Europe from just three plants and will switch production depending upon how local costs and demand conditions vary against exchange rate fluctuations. A further example is provided by Kellogs who manufacture their successful product Pringles in just two plants to meet worldwide demand. Likewise, Unilever’s long-established soap brand, Pears, is produced in India for world markets.

Such strategies have become widespread as ‘global thinking’ becomes the dominant mindset.

However, a number of crucial logistics trade-offs may be overlooked in what might possibly be a too-hasty search for low-cost producer status through greater economies of scale. The most obvious trade-off is the effect on transport costs and delivery lead-times. The costs of shipping products, often of relatively low value, across greater distances may erode some or all of the production cost saving. Similarly the longer lead-times involved may need to be countered by local stock holding, again possibly offsetting the production cost advantage.

Further problems of focused production may be encountered where the need for local packs exist, e.g. with labelling in different languages or even different brand names and packages for the same product. This problem might be overcome by ‘postponing’ the final packaging until closer to the point-of-sale.

Another issue is that created by customers ordering a variety of products from the same company on a single order but which are now produced in a number of focused factories in different locations. The solution here may be some type of transhipment or cross-dock operation where flows of goods from diverse localities and origins are merged for onward delivery to the customer.

Finally, what will be the impact on production flexibility of the trend towards focused factories where volume and economies of scale rule the day? Whilst these goals are not necessarily mutually incompatible it may be that organisations that put low-cost production at the top of their list of priorities may be at risk in markets where responsiveness and the ability to provide ‘variety’ are key success factors.

In response to these issues a number of companies are questioning decisions that previously were thought sound. For example, Sony used to manufacture their digital cameras and camcorders in China, attracted by the lower labour costs. However, they came to recognise that because life cycles were so short for these products it was better to bring the assembly back to Japan where the product design took place and, indeed, where most of the components originated. Other high-tech companies are also looking again at their offshore production and sourcing strategies for this same reason. Typically, less than 10 per cent of a high-tech company’s costs are direct labour. Hence the decision to source offshore, simply to save on labour costs, makes little sense if penalties are incurred elsewhere in the supply chain.

All in all it would appear that the total logistics impact of focused production will be complex and significant. To ensure that decisions are taken which are not sub-optimal, it will become even more important to undertake detailed analysis based upon total system modelling and simulation prior to making commitments that may later be regretted.

Centralised logistics at Lever Europe

Lever, part of the global corporation Unilever, manufacture and market a wide range of soaps, detergents and cleaners. As part of a drive to implement a European strategy for manufacturing and the supply chain, they created a centralised manufacturing and supply chain management structure – Lever Europe. A key part of this strategy involved a rationalisation of other production facilities from a total of 16 across western Europe to 11. The remaining facilities became ‘focused factories’, each one concentrating on certain product families. So, for example, most bar soaps for Europe are now made at Port Sunlight in England; Mannheim in Germany makes all the Dove soap products, not just for Europe but for much of the rest of the world; France focuses on machine dishwasher products, and so on.

Because national markets are now supplied from many different European sources, they have retained distribution facilities in each country to act as a local consolidation centre for final delivery to customers.

Whilst some significant production cost savings have been achieved, a certain amount of flexibility has been lost. There is still a high level of variation in requirement by individual market. Many countries sell the same product but under different brand names; the languages are different, hence the need for local packs; sometimes the formulations also differ.

A further problem is that as retailers become more demanding in the delivery service they require, and as the trend towards JIT delivery continues the loss of flexibility becomes a problem. Even though manufacturing economies of scale are welcome, it has to be recognised that the achievement of these cost benefits may be offset by the loss of flexibility and responsiveness in the supply chain as a whole.

2 Centralisation of inventories

In the same way that the advent of globalisation has encouraged companies to rationalise production into fewer locations, so too has it led to a trend towards the centralisation of inventories. Making use of the well-known statistical fact that consolidating inventory into fewer locations can substantially reduce total inventory requirement, organisations have been steadily closing national warehouses and amalgamating them into regional distribution centres (RDCs) serving a much wider geographical area.

For example, Philips has reduced its consumer electronics products warehouses in western Europe from 22 to just four. Likewise Apple Computers replaced their 13 national warehouses with two European RDCs. Similar examples can be found in just about every industry.

Whilst the logic of centralisation is sound, it is becoming increasingly recognised that there may be even greater gains to be had by not physically centralising the inventory but rather by locating it strategically near the customer or the point of production but managing and controlling it centrally. This is the idea of ‘virtual’ or ‘electronic’ inventory. The idea is that by the use of information the organisation can achieve the same stock reduction that it would achieve through centralisation whilst retaining a greater flexibility by localising inventory. At the same time, the penalties of centralising physical stock holding are reduced, i.e. double handling, higher transport charges and possibly longer total pipelines.

One of the arguments for centralised inventory is that advantage can be taken of the ‘square root rule’.2 Whilst an approximation, this rule of thumb provides an indication of the opportunity for inventory reduction that is possible through holding inventory in fewer locations. The rule states that the reduction in total safety stock that can be expected through reducing the number of stock locations is proportional to the square root of the number of stock locations before and after rationalisation. Thus, if previously there were 25 stock locations and now there are only four then the overall reduction in inventory would be in the ratio of ![]() to

to ![]() or 5:2, i.e. a 60 per cent reduction.

or 5:2, i.e. a 60 per cent reduction.

Many organisations are now recognising the advantage of managing worldwide inventories on a centralised basis. To do so successfully, however, requires an information system that can provide complete visibility of demand from one end of the pipeline to another in as close to real-time as possible. Equally such centralised systems will typically lead to higher transport costs in that products inevitably have to move greater distances and often high-cost air express will be necessary to ensure short lead-times for delivery to the customer.

Xerox, in its management of its European spares business, has demonstrated how great benefits can be derived by centralising the control of inventory and by using information systems and, in so doing, enabling a much higher service to its engineers to be provided but with only half the total inventory. SKF is another company that for many years has been driving down its European inventory of bearings whilst still improving service to its customers. Again, the means to this remarkable achievement has been through a centralised information system.

3 Postponement and localisation

Although the trend to global brands and products continues, it should be recognised that there are still significant local differences in customer and consumer requirements. Even within a relatively compact market like western Europe there are major differences in consumer tastes and, of course, languages. Hence there are a large number of markets where standard, global products would not be successful. Take, for example, the differences in preference for domestic appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines. Northern Europeans prefer larger refrigerators because they shop once a week rather than daily, whilst southern Europeans, shopping more frequently, prefer smaller ones. Similarly, Britons consume more frozen foods than most other European countries and thus require more freezer space.

In the case of washing machines, there are differences in preference for top-loading versus front-loading machines – in the UK almost all the machines purchased are front loaders whilst in France the reverse is true.

How is it possible to reconcile the need to meet local requirements whilst seeking to organise logistics on a global basis? Ideally organisations would like to achieve the benefits of standardisation in terms of cost reduction whilst maximising their marketing success through localisation.

One strategy that is increasingly being adopted is the idea of postponement discussed earlier in this book. Postponement, or delayed configuration, is based on the principle of seeking to design products using common platforms, components or modules, but where the final assembly or customisation does not take place until the final market destination and/or customer requirement is known.

There are several advantages of the strategy of postponement. Firstly, inventory can be held at a generic level so that there will be fewer stock keeping variants and hence less inventory in total. Secondly, because the inventory is generic, its flexibility is greater, meaning that the same components, modules or platforms can be embodied in a variety of end products. Thirdly, forecasting is easier at the generic level than at the level of the finished item. This last point is particularly relevant in global markets where local forecasts will be less accurate than a forecast for worldwide volume. Furthermore, the ability to customise products locally means that a higher level of variety may be offered at lower total cost – this is the principle of ‘mass customisation’.

To take full advantage of the possibilities offered by postponement often requires a ‘design for localisation’ philosophy. Products and processes must be designed and engineered in such a way that semi-finished product can be assembled, configured and finished to provide the highest level of variety to customers based upon the smallest number of standard modules or components. In many cases the final finishing will take place in the local market, perhaps at a distribution centre, and, increasingly, the physical activity outsourced to a third-party logistics service provider.

Gaining visibility in the global pipeline

One of the features of global pipelines is that there is often a higher level of uncertainty about the status of a shipment whilst in transit. This uncertainty is made worse by the many stages in a typical global pipeline as a product flows from factory to port, from the port to its country of destination, through customs clearance and so on until it finally reaches the point where it is required. Not surprisingly there is a high degree of variation in these extended pipelines.

Shipping, consolidation and customs clearance all contribute to delays and variability in the end-to-end lead-time of global supply chains. This is highlighted in the typical example shown in Table 10.1 below. This can be a major issue for companies as they increasingly go global. It has the consequence that local managers tend to compensate for this unreliability by over-ordering and by building inventory buffers.

Table 10.1 End-to-end lead-time variability (days)

One emerging tool that could greatly improve the visibility across complex global supply chains is supply chain event management.

Supply chain event management (SCEM) is the term given to the process of monitoring the planned sequence of activities along a supply chain and the subsequent reporting of any divergence from that plan. Ideally SCEM will also enable a proactive, even automatic, response to deviations from the plan.

The SCEM system should act like an intensive care monitor in a hospital. To use an intensive care monitor, the doctor places probes at strategic points on the patient’s body; each measures a discrete and different function – temperature, respiration rate, blood pressure. The monitor is programmed with separate upper and lower control limits for each probe and for each patient. If any of the watched bodily functions go above or below the defined tolerance, the monitor sets off an alarm to the doctor for immediate follow-up and corrective action. The SCEM application should act in the same manner.

‘The company determines its unique measurement points along its supply chain and installs probes. The company then programmes the SCEM application to monitor the plan-to-actual supply chain progress, and establishes upper and lower control limits. If any of the control limits are exceeded, or if anomalies occur, the application publishes alerts or alarms so that the functional manager can take appropriate corrective action.’

Source: Styles, Peter, ‘Determining Supply Chain Event Management’, in Achieving Supply Chain Excellence Through Technology, Montgomery Research, San Francisco, 2002.

The Internet can provide the means whereby SCEM reporting systems can link together even widely dispersed partners in global supply chains. ‘Cloud’-based computer systems enable independent organisations with different information systems to share data easily. The key requirement though is not technological, it is the willingness of the different entities in a supply chain to work in a collaborative mode and to agree to share information.

SCEM enables organisations to gain visibility upstream and downstream of their own operations and to assume an active rather than a passive approach to supply chain risk. Figure 10.2 shows the progression from the traditional, limited scope of supply chain visibility to the intended goal of an ‘intelligent’ supply chain information system.

Figure 10.2 The progression to supply chain event management

Event management software is now available from a number of providers. The principles underpinning event management are that ‘intelligent agents’ are created within the software that are instructed to respond within predetermined decision rules, e.g. upper and lower limits for inventory levels at different stages in a supply chain. These agents monitor the critical stages in a process and issue alerts when deviations from required performance occurs. The agents can also be instructed to take corrective action where necessary, and they can identify trends and anomalies and report back to supply chain managers on emerging situations that might require pre-emptive attention.

Whilst event management is primarily a tool for managing processes, its advantage is that it can look across networks, thus enabling connected processes to be monitored and, if necessary, modified.

Clearly the complexity of most supply networks is such that in reality event management needs to be restricted to the critical paths in that network. Critical paths might be typified by features such as long lead-times to react to unplanned events, reliance on single-source suppliers, bottlenecks, etc.

Event management is rooted in the concept of workflow and milestones, and Figure 10.3 uses nodes and links to illustrate the idea of workflow across the supply chain. Once a chain has been described in terms of the nodes that are in place and the links that have been established, the controls that have been defined respond to events across the chain. An event is a conversion of material at a node in the chain or a movement of material between nodes in the chain.

When an event does not occur on time and/or in full, the system will automatically raise alerts and alarms through an escalation sequence to the managers controlling the chain, requiring them to take action.

Financing global supply chains

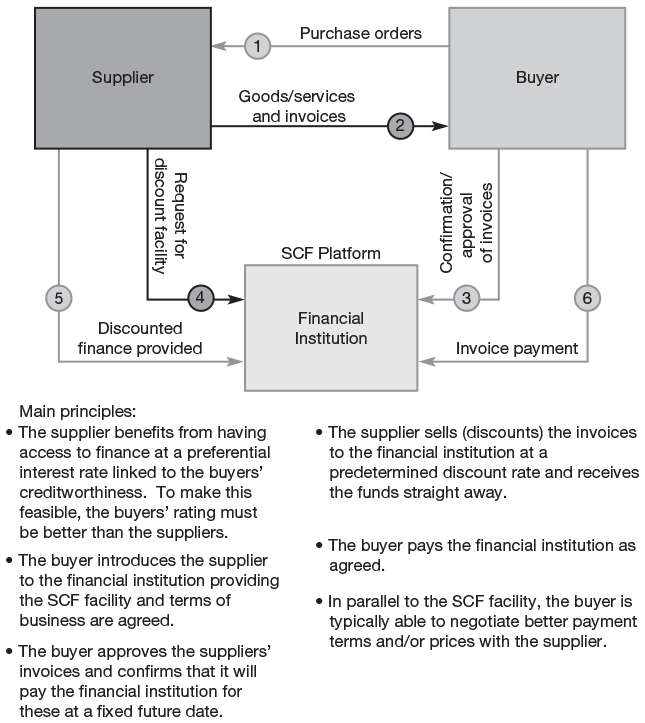

Inevitably, extended global supply chains will lock up greater amounts of working capital as longer pipelines imply a greater inventory requirement. In conventional international trading arrangements it has usually been the vendor who has to finance the pipeline, often having to factor invoices at a discount to improve cash flow.

More recently a different approach has emerged which is rapidly gaining acceptance, sometimes known as ‘supply chain finance’. The idea is that because often the customer is bigger than its suppliers and sometimes more soundly based financially, they – the customer – can access finance at a lower cost than the supplier. Using a financial intermediary – usually a bank – the buyer’s credit rating advantage enables a lower financing cost to be applied to the transaction. Figure 10.4 summarises the process.

Organising for global logistics

As companies have extended their supply chains internationally, they have been forced to confront the issue of how to structure their global logistics organisation. In their different ways these companies have moved towards the same conclusion: effectiveness in global logistics can only be achieved through a greater element of centralisation. This in many respects runs counter to much of the conventional wisdom, which tends to argue that decision-making responsibility should be devolved and decentralised at least to the strategic business unit level. This philosophy has manifested itself in many companies in the form of strong local management, often with autonomous decision making at the country level. Good though this may be for encouraging local initiatives, it tends to be dysfunctional when integrated global strategies are required.

Figure 10.3 Event management across the supply chain

Source: Cranfield School of Management, Creating Resilient Supply Chains, Report on behalf of the Department for Transport, Cranfield School of Management, Cranfield University, 2003

Clearly there will still be many areas where local decision making will be preferable – for example, sales strategy and, possibly, promotional and marketing communications strategy. Likewise the implementation of global strategy can still be adjusted to take account of national differences and requirements.

How then can the appropriate balance of global versus local decision making be achieved in formulating and implementing logistics strategy?

Because specific market environments and industry characteristics will differ from company to company, it is dangerous to offer all-embracing solutions. However, a number of general principles are beginning to emerge:

- The strategic structuring and overall control of logistics flows must be centralised to achieve worldwide optimisation of costs.

- The control and management of customer service must be localised against the requirements of specific markets to ensure competitive advantage is gained and maintained.

- As the trend towards outsourcing everything except core competencies increases then so does the need for global co-ordination.

- A global logistics information system is the prerequisite for enabling the achievement of local service needs whilst seeking global cost optimisation.

1 Structure and control

If the potential trade-offs in rationalising sourcing, production and distribution across national boundaries are to be achieved, then it is essential that a central decision-making structure for logistics is established. Many companies that are active on an international basis find that they are constrained in their search for global optimisation by strongly entrenched local systems and structures. Only through centralised planning and co-ordination of logistics can the organisation hope to achieve the twin goals of cost minimisation and service maximisation.

For example, location decisions are a basic determinant of profitability in international logistics. The decision on where to manufacture, to assemble, to store, to transship and to consolidate can make the difference between profit and loss. Because of international differences in basic factor costs and because of exchange rate movements, location decisions are fundamental. In addition, these decisions tend to involve investment in fixed assets in the form of facilities and equipment. Decisions taken today can therefore have a continuing impact over time on the company’s financial and competitive position.

As the trend towards global manufacturing continues, organisations will increasingly need to look at location decisions through total cost analysis. The requirement here is for improved access to activity-related costs such as manufacturing, transportation and handling. Accurate information on inventory holding costs and the cost/benefit of postponement also becomes a key variable in location decisions.

One increasingly important motivation for moving to a centralised structure for supply chain planning and control – particularly for larger organisations – is to enable the creation of a ‘tax efficient’ supply chain. Where it can be demonstrated that the global network is planned and managed from a central location then the case can be made, to the tax authority, that the location of what is termed the ‘principal structure’ of the business is in that location. As a result many companies have chosen to locate their supply chain planning teams and senior supply chain executives to countries such as Switzerland or Singapore.

The opportunities for reducing costs and improving throughput efficiency by a reappraisal of the global logistics network, and in particular manufacturing and inventory locations, can be substantial. By their very nature, decisions on location in a global network can only be taken centrally.

2 Customer service management

Because local markets have their own specific characteristics and needs there is considerable advantage to be achieved by shaping marketing strategies locally – albeit within overall global guidelines. This is particularly true of customer service management where the opportunities for tailoring service against individual customer requirements are great. The management of customer service involves the monitoring of service needs as well as performance and extends to the management of the entire order fulfilment process – from order through to delivery. Whilst order fulfilment systems are increasingly global and centrally managed there will always remain the need to have strong local customer service management.

Key account management (KAM) has become a widely adopted approach for managing the interfaces between suppliers and their global customers. Because of the growing shift in the balance of power in many industries, it is now a critical prerequisite for commercial success that suppliers tailor their service offerings to meet the requirements of individual customers. The purpose of KAM in a global business is to ensure that all the resources of the supplier are harnessed to deliver solutions that are specific to a particular customer. This contrasts with the ‘one size fits all’ approach to global customer service which typified many companies’ policies in the past.

3 Outsourcing and partnerships

As we have previously noted, one of the greatest changes in the global business today is the trend towards outsourcing. Not just outsourcing the procurement of materials and components, but also outsourcing of services that traditionally have been provided in-house. The logic of this trend is that the organisation will increasingly focus on those activities in the value chain where it has a distinctive advantage – the core competencies of the business – and everything else it will outsource. This movement has been particularly evident in logistics where the provision of transport, warehousing and inventory control is increasingly subcontracted to specialists or logistics partners.

For many companies, outsourcing their manufacturing or assembly operations has become the norm. The use of contract manufacturers is widespread in many industries as companies seek to take advantage of more efficient and specialised service providers.

To manage and control this network of partners and suppliers requires a blend of both central and local involvement. The argument once again is that the strategic decisions need to be taken centrally, with the monitoring and control of supplier performance and day-to-day liaison with logistics partners being best managed at a local level.

4 Logistics information

The management of global logistics is in reality the management of information flows. The information system is the mechanism whereby the complex flows of materials, parts, sub-assemblies and finished products can be co-ordinated to achieve cost-effective service. Any organisation with aspirations to global leadership is dependent upon the visibility it can gain of materials flows, inventories and demand throughout the pipeline. Without the ability to see down the pipeline into end-user markets, to read actual demand and subsequently to manage replenishment in virtual real-time, the system is doomed to depend upon inventory. To ‘substitute information for inventory’ has become something of a cliché but it should be a prime objective nevertheless. Time lapses in information flows are directly translated into inventory. The great advances that are being made in introducing ‘QR’ logistics systems are all based upon information flow from the point of actual demand directly into the supplier’s logistics and replenishment systems. On a global scale, we typically find that the presence of intervening inventories between the plant and the marketplace obscure the view of real demand. Hence the need for information systems that can read demand at every level in the pipeline and provide the driving power for a centrally controlled logistics system.

To better manage the mass of data and information that underpins global supply chains, many companies have established what are sometimes termed ‘logistics control towers’. Companies such as P&G have developed sophisticated information hubs which enable them to utilise powerful ‘sense and respond’ capabilities to manage their global supply and demand networks. These control towers not only enable day-to-day operations to be better managed but can also make use of demand-driven analytic tools to identify trends and to understand fundamental changes in the marketplace.

Thinking global, acting local

The implementation of global pipeline control is highly dependent upon the ability of the organisation to find the correct balance between central control and local management. It is unwise to be too prescriptive but the experience that global organisations are gaining every day suggests that certain tasks and functions lend themselves to central control and others to local management. Table 10.2 summarises some of the possibilities.

Table 10.2 Global co-ordination and local management

| Global | Local | ||

| • |

Network structuring for production and transportation optimisation | • |

Customer service management |

| • | Information systems development and control | • | Gathering market intelligence |

| • | Inventory positioning | • | Warehouse management and local delivery |

| • | Sourcing decisions | • | Customer profitability analyses |

| • | International transport mode and sourcing decisions | • | Liaison with local sales and marketing management |

| • | Trade-off analyses and supply chain cost control | • | Human resource management |

Much has been learned in the past about the opportunities for cost and service enhancement through better management of logistics at a national level. Now organisations are faced with applying those lessons on a much broader stage. As international competition becomes more intense and as national barriers to trade gradually reduce, the era of the global business has arrived. Increasingly the difference between success and failure in the global marketplace will be determined not by the sophistication of product technology or even of marketing communications, but rather by the way in which we manage and control the global logistics pipeline.

The future of global sourcing

One of the most pronounced trends of recent decades has been the move of to offshore sourcing, often motivated by the opportunity to make or buy products or materials at significantly lower prices than could be obtained locally. Companies such as the large British retailer Marks and Spencers, who once made it a point of policy to source the majority of their clothing products in the United Kingdom, moved most of their sourcing to low-cost countries, particularly in the Far East. Manufacturers, too, closed down western European or North America factories and sought out cheaper places to make things – often many thousands of miles away from their major markets.

At the time that many of these offshore sourcing and manufacturing decisions were being made, the cost differential between traditional sources and the new low-cost locations was significant. However, in recent years there has been a growing realisation that the true cost of global sourcing may be greater than originally thought.3 Not only have the costs of transport increased in many cases, but exchange rate fluctuations and the need for higher levels of inventory because of longer and more variable lead-times have impacted total costs. In short life cycle markets there is the additional risk of obsolescence with consequent markdowns or write-offs. Other costs that can arise may relate to quality problems and loss of intellectual property. With growing concern for environmental issues, there is also now the emerging issue of ‘carbon footprints’ (to be dealt with in more detail in Chapter 15).

All of these issues are now causing many companies and organisations to review their offshore sourcing/manufacturing decisions. Whilst there will always be a case for low-cost country sourcing for many products, it will not universally be the case as the following case suggests.

Hornby: bringing production back home

Hornby is a long-established business involved principally in the manufacture of model trains, cars and planes. Established in the UK in 1907 – originally named Meccano Ltd, producing the classic construction kits – the company has been through many ups and downs. At the end of the twentieth century, in a search for a lower cost base, the company moved production of its toys to China and by 2002 no longer had a UK manufacturing operation.

However as the toy market became more competitive with product life cycles shortening and retail customers wanting shorter delivery lead-times, Hornby realised that in order to complete it had to review its sourcing strategy. In 2013, production of a new range of Airfix model aircraft was transferred to the UK and as the labour costs in China continued to increase the likelihood was that more production would return home.

As the Hornby case highlights, simply looking for low-cost manufacturing solutions can be self-defeating when the market is demanding higher levels of responsiveness. In Chapter 2 we briefly introduced the concept of the ‘Total Cost of Ownership’ (TCO). The idea is that any organisation when making a sourcing decision should take a wider view of cost than simply the purchase price. The TCO will include transport costs, inventory financing costs, obsolescence and mark-down costs as well as factoring in the possibility of quality problems, supply chain disruptions and the loss of intellectual property.

One problem facing some businesses is that if they did want to take the decision to ‘re-shore’, i.e. bring manufacturing back to its original country base, it may not be that easy. Often, once factories close then the specialist skills and knowledge are lost, in other cases the supply chain of machinery providers, component manufacturers and raw material producers may also disappear. One recent study looking at the viability of bringing back textile manufacturing on a larger scale to the UK highlighted the scale of the challenge.4

In any case, the argument should not really be about ‘off-shoring’ or ‘re-shoring’ but rather the goal should be ‘right-shoring’ – meaning that wherever possible sourcing and manufacturing should take place in the location that makes most sense.

References

1. Levitt, T., ‘The Globalization of Markets’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 61, May–June 1983.

2. Sussams, J.E., ‘Buffer Stocks and the Square Root Law’, Focus, Institute of Logistics, UK, Vol. 5, No. 5, 1986.

3. Centre for Logistics & Supply Chain management (2008), The True Costs of Global Sourcing, Cranfield School of Management, UK

4. Repatriation of UK Textiles Manufacture (2015), The Alliance Project Team, Greater Manchester Combined Authority, UK.