15

Reverse Logistics: A New Wave

After reading the chapter, the students should be able to understand:

- Concepts, scope and objectives of reverse logistics

- Reverse logistics system design considerations

- How reverse logistics is used as a competitive tool

In a competitive environment, the philosophy of accepting product returns as a competitive tool has resulted in huge challenges to logisticians. Today, logistical support means going beyond “forward logistics” to include product recall, product disposal and product recycling. The logistics design objectives include reverse material flow system to support the life cycle of the product.

“Reverse logistical competency is a result of worldwide attention to environmental concern.”

—Dale S. Rogers and Tibben-Lembke, Ronald1

15.1 WHY REVERSE LOGISTICS?

Traditionally, in the supply chain of an organization there is a unidirectional flow of goods, that is, from the manufacturer to the end-user. Almost the entire attention of a logistician has been focused on the “forward” logistics activities. Once the product is sold and delivered to the user, the manufacturer feels that there is an end to his responsibility. Manufacturers think that their responsibility is limited to the extent of replacement of defective products covered under the warranty or those damaged during transit. What is happening to the used materials, packaging waste, disposable product waste generated by the finished products supplied by them? The leftover material and wrappers cause environmental pollution and create problems of disposal for the civic authority. However, in the wake of growing concern about environmental pollution, developed countries across the world have passed legislations that require manufacturers to take care of products discarded by their customers after usage. Leading corporations across the world are taking this as an opportunity to develop a system for reverse material flow. They are focusing on reverse logistics in order to use it as a tool for competitive advantage. It is estimated that reverse logistics costs account for approximately 0.5 per cent of the total United States gross domestic product (GDP).2 Therefore, reverse logistics is becoming an integral component of the profitability and competitive position of retailers and manufacturers.

Reverse logistics may be defined as a process of moving goods from their place of use to their place of manufacture for reprocessing, refilling, repairs or waste disposal. It is a planned process of goods movement in the reverse direction, done in an effective and cost-efficient manner through an organized network. It can be a stand-alone or an integrated system in the company’s supply chain.

15.2 SCOPE OF REVERSE LOGISTICS

Reverse logistics, though considered a drain on the company’s profits, can be leveraged as a tool for customer satisfaction in today’s competitive markets. More and more manufacturing firms are thinking of incorporating the revere logistics system in their supply chain process. The reasons for this are:

- Growing public concern about environment pollution

- Government regulations on product recycling and waste disposal

- Growing consumerism

- Stiff competition

The reverse logistics network can be used for various purposes such as refilling, repairs, refurbishing, remanufacturing, and so on. Depending on the nature of the product, unit value, sales volume and distribution channel, reverse logistics can be organized and designed into a system for the following activities.

Refilling

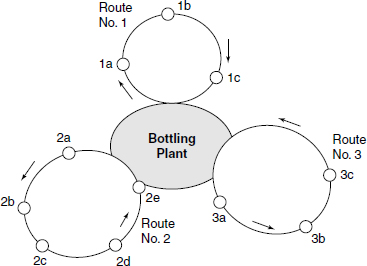

In industries such as soft drinks, wine, oil and LPG distribution, reverse logistics is integrated to their regular supply chain because of the reusable nature of the packages, such as glass bottles, tin containers and metal cylinders. In the case of soft drinks industry, the delivery van enroute to retailers a, b, c (see Figure 15.1) delivers the filled bottles and collects the same number of empty bottles from them for delivery to the factory. No extra transportation costs are involved in the process, as the delivery van originates and terminates its journey at the factory, where these reusable bottles are refilled for redelivery to the customers. Such an arrangement is called a “hub and spoke distribution system.”

Figure 15.1 Reverse goods flow for refilling

A similar arrangement is in use by the petroleum companies (Hindustan Petroleum, Bharat Petroleum and others) for refilling of LPG cylinders. Truckloads of filled LPG cylinders are dispatched from the bottling plant for delivery to the dealer’s godown. On return trip, the same truck carries the empty cylinders from the dealers for depositing at the bottling plant. With metal cylinders such as these, the recovery rate (due to less damage and prolonged life of the cylinders) is to the extent of 99.9 per cent.

The UB Group, at one of their plants, fills 3 lakhs beer bottles of London Pilsner (a leading beer brand in Maharashtra) every day. The recovery rate of empty glass bottles from the market is 92 per cent, as 3 per cent of the bottles are broken and 5 per cent of them are lost or put to other usages. Due to the cost difference of 20–25 per cent between new and old glass bottles, which contributes to the extent of 12–15 per cent in the total manufacturing cost of the product, the firm saves a lot by using the used bottles. They have developed a stand-alone reverse logistics system for recovery of the empty bottles through scrap vendors, who collect these bottles at a throwaway price from such places as hotels, clubs, pubs and bars.

Logistics service suppliers, who lease pallets to their various clients for packing and moving goods, keep a pool of pallets at fixed locations. Customers draw the pallets for use and deposit them at the assigned centre after usage. The damaged pallets are repaired or replaced regularly, keeping the required quantity in circulation. The return of the pallets is on an exchange basis. The pallet supplier is the common link between the buyer and the seller, with whom he co-ordinates the reverse logistics operation. This system is quite common in developed countries.

In India, box containers used in the multimodal transportation system are leased by the Container Lease Corporation Ltd. (CLCL), which keeps an inventory of empty box containers at Inland Container Depots (ICDs) operated by the Container Corporation of India (CCI) or private agencies. Customer requirements of containers for packaging and movement of goods in the domestic or foreign markets are drawn from these depots. The containers are loaded at container freight stations operated by the CCI or others. The empty containers, after de-stuffing of materials, are deposited at the container depot nearest to the place of delivery for further reuse and reverse flow to the place of origin. Thus, the entire movement of containers in forward and reverse logistics is controlled by CLCL.

Shaw Wallace has integrated the reverse flow of empty bottles with their regular forward distribution system. The empty bottles are collected at the area distribution warehouse with the help of their dealers, who are in touch with hotels and scrap dealers. The latter have their own network to collect empty wine bottles from households, hotels, clubs and pubs. The bottles thus collected at field warehouses are sent back to the factory for refilling. The recovery of empty bottles is to the extent of 85–88 per cent of the supply.

Repairs and Refurbishing

This is a regular feature for service-based products under warranty, which manufacturers have to incorporate in their product offerings. Almost all consumer durables such as television sets, audio systems, washing machines, fans, and refrigerators, as well as all industrial products need repairs on a regular basis. Refurbishing is done for the goods returned by customers during the warranty period because of damage, defects or their performance being below the promised level. Manufacturers establish the reverse logistics system not only for offering free service during the warranty period of the product, but also for extending services beyond the warranty period on a chargeable basis. In addition to extending value-added services to customers, the system is a major revenue earner for the company. The reverse logistics system operates through the company’s service centres, where the repair and refurbishing take place. The collection of products is done through the dealer network. The collected products are dispatched to the nearest service centre for overhaul, repair or refurbishing. The documentation and payment collection is the responsibility of the concerned dealer. For a large-value industrial product, coordinating with and locating the customer does not pose any problem, as the number of customers is small, and besides, they are personally known.

Product Recall

This is an emergency situation wherein the products distributed in the markets are called back to the factory because of any of the following:

- Product not giving the guaranteed performance

- Quality complaints from many customers

- Defective product causing harm to human life

- Products beyond the expiry date

- Products with defective design

- Incomplete product

- Violation of government regulations

- Ethical consideration

- To save the company’s image

The above situations may arise very rarely. The likely reasons may be production shortcuts, bypassing stage inspections, employee negligence, human error or management negligence. Product recall in these situations puts a huge financial burden on the company. No organization designs in advance a reverse product flow system for deployment in anticipation of such eventualities. However, many firms, on such occasions, have shown a great deal of organizing ability in mobilizing the company’s resources to achieve this time-bound objective.

In the 1980s, a leading Indian auto manufacturer launched a multi-utility vehicle in the Indian market. Soon after the launch, there were large-scale complaints from customers due to the defective gearbox design. All the vehicles dispatched to the customers were called back within a short time by deploying their dealer network and the company’s sales force, so they could be refitted with the gearbox of improved design. In the meantime, redesigning of the gearbox was competed on a war footing.

Johnson & Johnson Health Care, a U.S. multinational company, introduced milk powder in the South African markets as a substitute for breastfed milk for newborn babies. However, due to large-scale deaths of babies who consumed the powdered milk, Johnson & Johnson Health Care called back the entire unsold powdered milk stocks in the market under a time-bound program and gave compensations to the victims on ethical grounds. The cause of the deaths was contaminated milk prepared under unhygienic conditions and not the milk powder. The company failed to educate the mothers on a hygienic process for milk preparation during its sales campaign.

The scope and effectiveness of the recall process is dependent on the type of the product, its distribution network, consumption pattern and unit value. The recall process is very effective in the case of industrial products of high unit value, dispatched directly to a small number of customers. The customer being knowledgeable, extends his/her cooperation in the process. However, in the case of mass-consumed products distributed through a multi-level channel structure, identifying the product location becomes problematic. It is easier to trace the product location within the boundaries of the channel network. Once the product is sold and handed over to the user, the degree of effectiveness of the product recall process reduces drastically because of the following reasons:

- Lack of customer database

- No motivation on the part of the customer to return the product

- Product not meant for critical use

In the case of service-based products, such as consumer durables, which are accompanied with warranty cards, the product can be located, provided the documentation is maintained at the point of sale. This makes the recall process easy.

In the wake of stiff competition and growing consumerism, many manufacturers have put in place a product recall system as a value-added service to build competitiveness. The recall of defective products during warranty period is now the most common feature of customer service offers. In fact, it is cost burden on the part of manufacturers. However, many companies now consider product recall as an opportunity to increase customer satisfaction and an asset recovery operation as well. Nestle India, for example, take back the yogurt every day from their distributors after the expiry of its 24-hour shelf life. Similarly, Monginis, a Mumbai-based leading bakery products producer, collect the cakes from their distributors when the product’s shelf life is over. The van delivering fresh products to the distributors collects by default the products that are not sold and their shelf life is over.

Recycling and Waste Disposal

The left out materials, used products and wrapper wastes cause environmental pollution and create problems of disposal. Hence, in developed countries, governments are devising regulations to make manufacturers responsible for minimizing the waste by way of recycling the products. Germany is the first country in the world to implement such regulations. According to the law, the manufacturer is responsible for taking back pallets, cardboard boxes, wrappers, strapping and such other things that are used for protecting the products during transit. They have implemented a three-stage packaging ordinance. In the first stage, wrappers or packaging wastes are collected from households by retailers. In the second stage, these waste items go from the retailers to the manufacturers who, in the third stage, send them across to the packaging manufacturer for recycling or disposal. The levy for recycling is indicated on the product by green dots. In Germany, the FMCG manufacturers have jointly promoted Dealers System Deutschland (DSD) with common funding for collection of packaging waste of FMCG products. They have reduced cost of retrieving and recycling the packing waste through economies of scale by joining hands together. In the United States there is a law to take back from customers car batteries, soda bottles and so on.

Fig. 15.2 Three-stage reverse logistics system for car recycling

In Europe, Volkswagon (a leading auto manufacturer) is the first company that has effectively developed a car recycling supply chain system. The car is mostly an assembly of components made out of metal that can be easily recycled.

REVERSE LOGISTICS IN PRACTICE: BMW ‘REVERSE LOGISTICS’ FOR USED CARS …

In Germany, if a car completes 12–15 years on the road, it is the responsibility of the owner to pay a requisite amount and hand over the used vehicle to the automobile manufacturer through the authorized collection centre or dealer. BMW has developed an exclusive dismantling plant for car recycling. The used cars are collected through the reverse logistics system, which is a part of their forward supply chain. The plant is equipped with high-tech tools, and special methods are employed for rapidly dismantling cars to extract useful stuff from them. With the existing facilities, it takes 20 minutes to dismantle the full car. They have this plant at Lohhof near Munich, which is the only facility promoted by BMW as a competence centre and technology forum for all matters relating to recycling of the vehicle. Every year they dismantle 20,000 cars at Lahhof, which is equivalent to 3600 tonnes in weight. This comprises 1700 tonnes of body shell, 200 tonnes of operating fuel (oil, fuel), 20 tonnes of plastics, 30 tonnes of non-ferrous metal and 5 tonnes of batteries. The BMW plant earns USD 1.5 million by selling dismantled parts from end-of-life vehicles (ELVs). The biggest challenge in the dismantling and recycling task is to tackle material like mercury, cadmium, haxavalent chromium and lead that are now a part of vehicles. According to the European Union (EU) directives, there is a ban on the use of the above materials from 1 July 2003 on environmental grounds. Mercury is used in headlight bulbs, lead and cadmium in batteries, and so on. Although BMW is paid for the old vehicles and earns USD 1.5 million p.a. by selling used parts, however, these earnings are far less than the investments on the facility they have developed. BMW has created a database on dismantling and recycling parts, which is called IDIS, with active inputs from the 20 carmakers and contains information on 2000 components fabricated by these manufacturers. With lessons learnt from BMW, other auto manufacturers like Mercedes and Porsche are developing their recycling and dismantling facilities due to stringent environmental regulations in the EU. In Germany alone, 1.4 million ELVs get ready for recycling each year.

Source: Business Line, 4 June 2002.

Matushita Recycling Plant for Electronics

After the Japanese Government passed The Electric Home Appliances Recycling Law in April 2001, the Matushita group that sells its products under the brand name National and Panasonic set up the recycling plant in 2002 for processing one million units (TVs, refrigerators, air conditioners and other electronic goods) to reduce the national waste. They recover glass (57 per cent of the TV weight ), metals (80 per cent from air-conditioner) and plastics through waste recycling process. Matushita has set up a reverse logistics system for collection of used electronic equipments at specified collection centres in Japan. The customers have to pay nominal charges for products that are to be recycled. The charges for recycling are fixed by the manufacturers. At the Matushita plant the products of Toshiba, GE and JVC are also recycled.

Source: The Economic Times, 12 October 2002.

Seconds TV Industry in India

TV dealers collect old TV sets at INR 3000–4000 against exchange schemes to push the new stock. They resell the old models in other markets at INR 6000 or more, covering transportation and minor repair charges. The seconds TV market in India is estimated at 3–4 lakh pieces per annum valued at INR 180–240 cr.

Source: ET Knowledge Series —2002.

For product refurbishing, for example, Sony USA, a consumer electronic giant operating in the United States, uses its regular dealer network for reverse flow of video or audio systems returned by the customers within the warranty period.

In India, the Supreme Court is in the process of imposing a ban on charging and discharging of automotive batteries on the grounds of pollution, and the union government is coming out with a new legislation making it mandatory to return used batteries to manufacturers for recycling and disposal.

Remanufacturing

Manufacturers in the developed countries are putting into practice a new concept of “remanufacturing” that emerged in the late 1990s. During usage the product undergoes wear and tear. The worn parts are replaced with the new ones and the performance of the product is upgraded to the level of the new one. The practice is more prevalent in the defence establishments where fighter planes are checked after each flight for their performance level, which is every time brought to the level of new one without any compromise on the quality front. Similarly, equipments sold in the markets can be checked after use to qualify for the remanufacturing process and brought to the remanufacturing unit. A leading cell phone company in Europe has outsourced its remanufacturing activities to a few vendors in Europe and developed a separate network for reverse flow of the used or discarded products held by the customer for only short periods before switching over to the latest models. The company has identified a huge market for remanufactured products in the developing countries. The investment in remanufacturing and related reverse logistics supply chain can be justified on the basis of economies of scale. A critic, however, says that the remanufacturing will solve the problem of waste disposal in developed countries, but create new dumping grounds in the developing countries.

15.3 SYSTEM DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

In 1996, the auto giant General Motors had a problem handling 30,000 defective parts per month for replacement within the warranty period, which were returned by customers from various places to their plants at different locations. To overcome this problem they, along with UPS Worldwide Logistics, jointly developed a reverse logistics system using their 200 dealers as collection and disposal centres to initiate documentation and pre-checks for further dispatch and processing to GM’s Orion plant. The centralization simplified the process for GM engineers and suppliers wanting to examine the parts to understand what improvements are necessary. As all the parts are sent to one location and UPS tracks their shipment, online feedback to customers is feasible. The success of the reserve logistics system in achieving the desired objectives will depend on the efficiency and effectiveness of the following subsystems.

Product Location

The first step in the callback process is to identify the product location in the physical distribution system of the firm. The product may be lying in the company’s mother warehouse or distribution warehouse, dealer’s godown, or with the retailer or the customer. Locating the product becomes quicker and easier if it is in the company’s warehouse or depot, or with the distributor, where tracking can easily be done. But once it enters the retail network, the task becomes really difficult because of the large number of retailers, wide geographical spread and lack of proper documentation. This is even more true in the case of FMCG or mass-consumed low unit price products.

The product location becomes more difficult after it is sold and handed over to the customer. Locating the product is a bit easier in the case of industrial or high-value products, owing to the limited number of customers and the personal touch with clients as a result of direct selling.

Product Collection System

Once the product location is identified, the collection mechanism gets into operation. Collection can either be done through the company’s field force, channel members or a third party. However, proper guidelines or instructions have to be given to motivate the customer to return the products. The customer is biggest hurdle in the retrieval of the product, as he does not want to part with something that he owns. The collection centres should be located at the proper location to ensure wider coverage and minimum collection cost. The company’s intermediaries are the most effective centres in product callback, as far as cost and coverage are concerned. With proper training, the intermediaries can carry out the preliminary inspection of the called back/returned products before inducting the same into the system for further processing.

Product Recycling/Disposal Centeres

These centres may be the company’s manufacturing plant or the mother warehouse from where the finished products were dispatched to the market or some other fixed location in the reverse logistics network. The called-back products are inspected before they are further processed for repair, refurbishing, remanufacturing or waste disposal. The investments facilities for these activities depend on the objectives of the system, cost implication, complexity of the operations and the expected gains.

Documentation System

The tracing of the product location becomes easier, if the proper documentation is maintained at each channel level. However, at the time of handing over the product to the customer, the information on the user’s name, address, contact phone numbers, application, and other personal data, if collected through proper documentation, can form a good database that can be used in case of product callbacks. The product warranty card, with product and customer details duly filled in at the point of sale, is commonly issued for service-based products, such as consumer durables and industrial products. However, only the card remains with the customer as proof of purchase to be produced at the time of claims during the warranty period. No supporting record is usually maintained at the dealer’s end. Except for high-value industrial products, no records are kept by retailers for consumer durables or mass-consumed products. The documentation system in reverse logistics, however, ensures the maintenance of customer-product database at the point of sale. To ensure the smooth running of the system, a procedure has to be introduced for entry, exit and flow of the called-back products in the system for tracking and tracing.

Cost Implications

The reverse logistics system is a cost centre. However, these costs are incurred for achieving certain company objectives that can broadly be subdivided into the following activity heads:

- Product location (by company staff, channel member, or third party)

- Transportation

- Product collection (Customers > retailers > plant)

- Disposal (plant > suppliers > disposal)

- Refilling, repairs, refurbishing, remanufacturing and waste generation

- Documentation (for product tracking during entry, exit and flow in the system)

- Communication

Due to the cost implication, manufacturers invariably integrate the reverse logistics into their forward logistics system with little modifications. The same network components are geared up to accommodate the reverse flow of the products with the same efficiency and effectiveness. The investment and operating costs involved in tuning the existing “forward” flow system to “reverse” flow will be less than for a separate stand-alone system devoted only to reverse flow, unless it is designed on scale economies.

Legal Issues

Under the Indian regulations, excise-paid goods once sold by the manufacturer cannot be brought back to the plant without proper documentation and declaration made to the excise authority. This is a very cumbersome and time-consuming process and non-compliance may put manufacturer in the dock. For resale of repaired or refurbished goods, both the excise and sales tax authorities are involved and the clearing of such goods requires documentation, certifications and declarations. Hence, such activities are normally carried out at service centres or at the dealer’s premises.

In reverse logistics, the critical strategic points in network design are: acquisition/collection of returned/used products, testing and grading operations, reprocessing and redistribution/disposal. For reverse logistics to be successful, the collaboration of supply chain is very important. Technologies such as bar coding or radio-frequency identification (RFID) help in making reverse logistics more effective and responsive.

15.4 REVERSE LOGISTICS—A COMPETITIVE TOOL

In today’s fiercely competitive market environment, customer retention strategies play an important role. To retain the existing customers, manufacturers are creating switching barriers by extending value-added service to the customers.

Procedural efficiency in the logistics operations is enhancing the service capability of the firm to satisfy the customer. To remain competitive and differentiated, more and more firms across the world are displaying both speed and reliability in their service offerings, such as:

- Replacing defective goods

- Repairing the used product

- Refurbishing the returned product

- Calling back substandard or harmful goods

- Disposal of product waste

The additional services mentioned above are contributing to the competitiveness of the company operating in a regulatory environment. They are also creating customer value by providing a clean environment through reverse logistics services without any extra cost to the customer. Today, corporations across the world are leveraging reverse logistics for growth through enhancing the level of customer satisfaction beyond the traditional boundaries of product and service supply.

SUMMARY

Traditionally, almost all manufacturing firms focus their attention on “forward” logistics activities. However, during the past few years, because of changes in environmental laws, increased consumerism and stiff competition in the markets, use of effective reverse logistics as a competitive weapon became a necessity. Soft drink manufacturers have been practising reverse logistics for glass bottle refilling for many years. The cost advantage in reverse logistic is possible through the economies of scale. Today, many big corporations across the world have either developed a stand-alone reverse logistics system or integrated the same into their forward logistics system. The system design takes into consideration factors such as product locating system, product collection mechanism, documentation, product recycling/disposal centres, cost implication and legal aspects. In developed countries such as Germany and the United Sates, stringent environmental regulations have prompted the corporations to develop a three-tier product waste recycling/disposal model through reverse logistics. A separate stand-alone reverse logistics system has been developed by cell phone manufacturing companies for the remanufacturing of used products. For creating switching barriers for their customers, companies are offering value-added services to build the competitive edge. Corporations the world over are leveraging reverse logistics for customer satisfaction.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Discuss the role of reverse logistics in the company’s supply chain.

- “Reverse logistics competency is a result of worldwide attention to environmental concern.” Support your answer with illustrations.

- How is reverse logistics used as a tool for competitive advantage?

- Discuss the various design considerations for the reverse logistics system.

- Explain the concept of green marketing with illustrations. What is its relationship with reverse logistics?

- More and more companies are inclined to develop a reverse logistics system. What are the factors that encourage manufacturers to develop a reverse logistics system? Explain how the manufacturer benefits from a reverse logistics system.

INTERNET EXERCISES

- How can the problems associated with e-waste in India be resolved through an effective reverse logistics system? For understanding the severity of the e-waste problem, visit http://www.e-waste.in

- Reverse Logistics Executive Council is a collaboration of manufacturers, retailers and academicians, www.rlec.org. Find out from this website the initiatives taken by various organizations to set up a reverse logistics system.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowersox, D.J., and D.J. Closs. 2000. Logistical Management. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill, pp. 43.

Caldwell, Bruce. 1999. ‘Reverse Logistics.’ About Logistics and Supply Chain, 12 April.

Cooper, James. 1994. Logistics and Distribution Planning. London: Kogan Page, pp. 165–172.

Deborah, L. Bayles. 2001. E-Commerce Logistics and Fulfillment. Singapore: Pearson Education Asia, pp. 237–299.

Gattorna, John L. 1995. Handbook of Logistics and Distribution Management. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House, pp. 461–471.

Giuntini, Ron and Tom Andel. 1995. ‘Reverse Logistics Role Models’ Transportation and Distribution. 36 (4): 97–8.

Kopiciki, M.J., and L.L. Legg, V. Dassapa, and C. Maggioni. 1993. ‘Reuse and Recycling Reverse Logistics Opportunities.’ Oak Brook: II Council of Logistics Management, p. 2.

Lampe, M. and G.M Gazda. 1995. ‘Green Marketing in Europe and United States.’ International Business Review 4: 295–312.

Rogers, Dale and Tibben-Lembke, Ronald. 1999. ‘Reverse Logistics: Strategies and Techniques.’ Logistic and Management 7 (2): 15–26.

Rogers, Dale and Tibben-Lembke, Ronald. 2001. ‘An Examination of Reverse Logistics Practices.’ Journal of Business Logistics 22 (2): 129–148.

Shapiro, Jeremy F. 2002. Modelling the Supply Chain. Singapore: Thomson Asia, pp. 495–499.

Srivastava, Samir K. and Rajiv K. Srivastava. 2006. ‘Managing Product Returns for Reverse Logistics.’ International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics 36 (7): 524–546.

Tibben-Lembke, Ronald. 1998. ‘The Impact of Reverse Logistics on Total Cost of Ownership.’ Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6 (4): 51–60.

Tibben-Lembke, Ronald and Dale Rogers. 2002. ‘Differences Between Forward and Reverse Logistics in a Retail Environment’ Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 7: 5.

Tibben-Lembke, R.S. ‘Going Backwards: Reverse Logistics Trends and Practices.’ Reverse Logistics Executive Council, www.rlec.org

Tompkins, James A., and Dale A. Harmelink. 1994. Distribution Management Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 1–8.