23

CASES

23.1 Bharatcraft.com—Business Logistics System for an Online Selling Store

23.2 Phantom Glass Ltd—Seeking Solution to Curb Wasteful Warehousing Practices

23.3 N-Joy Tobacco Company—Aiming at Best Practices in Distribution

23.4 Jolly Snack Food Products Company—A Case for Freight Rationalization

23.5 Kapil Health Food Products—Mapping the Supply Chain for Weak Linkages

23.6 Priya Namak Company—Revamping the Distribution Structure

23.7 Cadbury Products—Lean Supply Chain through Demand Management

23.8 MWC Ltd.—Looking Beyond the Role of Warehousing

23.9 ROX Doc-Care—Meeting Market Requirements of Document Warehousing

23.10 Gattu Welding Electrodes—Restructuring Warehousing Network

23.11 Suman Crop Protection—Moving to the Cost-Effective and Efficient Logistics System

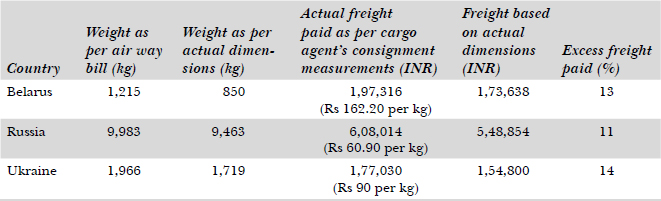

23.12 Ashwini Pharma Pvt. Ltd.—A Case of Logistical Packaging for Exports

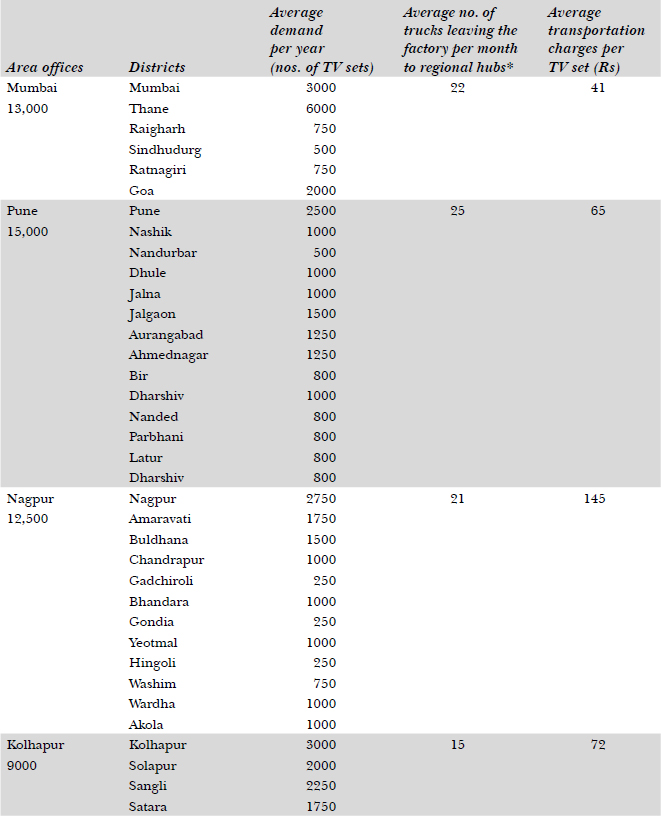

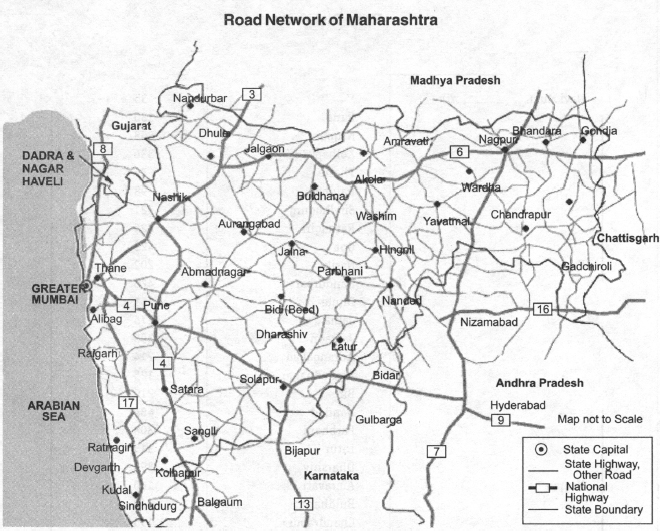

23.13 Aditya Digital TV—Deciding on Warehouse Locations

23.14 Karan Automotives Company—Restructuring Physical Distribution System

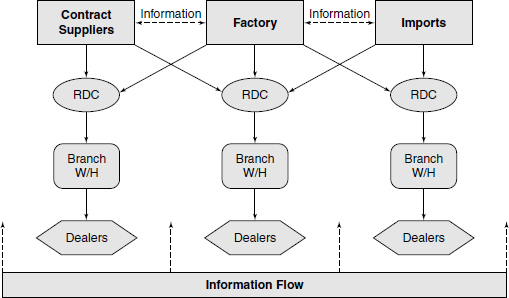

23.15 Mohini Electronics Ltd.—Supply Chain Initiative Reaping Benefits

23.16 Rubber Products—Redesigning Supply Chain on the Technology Platform

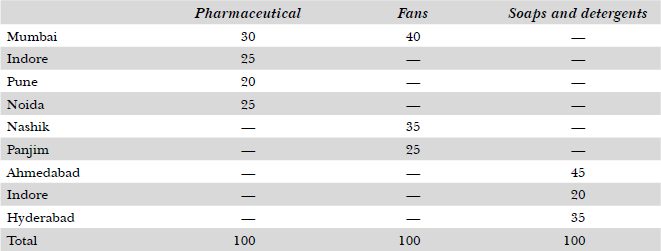

23.17 Tushar Enterprises—Consolidating Distribution Systems

23.18 Padmini Motors Ltd.—A Lean Supply Chain through the ‘Just-In-Time’ System

23.19 Dora Ceramic Tiles—Preparing to Meet Supply Chain Challenges of Tomorrow

23.20 Shree Cements—Freight Reduction through Transportation Mix

Case 23.1

BHARATCRAFT.COM*

Business Logistics System for an Online Selling Store

Bharatcrafts.com is a vertical portal for handicrafts from all over India. The portal is into online selling of handicrafts. This is a B2B and B2C portal. This company has no physical stores. They outsource 100 per cent of their product from the craftspeople and the same is then dispatched to the ultimate customer through the courier service. They have strategic alliances with the courier services and the craftspeople.

Whenever an order comes to them via the Internet, it gets processed and put into the sales and operations planning (S&OP) system. Here, in this system the order is checked to match it with the names of the craftspersons along with their addresses. The authenticity of the customer is checked by calling the telephone number provided by the customer; and for individual customers by the agents or regional office people. In case it is a bulk order from a dealer, then the reputation of the dealer is verified before placing the order with the craftspeople (see Figure 23.1.1).

Fig. 23.1.1

The craftsman is contacted via the Net if he/she has access to the Internet, or the message is conveyed telephonically. Delivery dates are confirmed from the concerned craftspeople and conveyed to the customer immediately. Payment can be made in two ways:

- Online transaction using the credit card

- Payment on delivery after authentication

A general inspection of the product is done to see that there is no slip or misplacement of the products. When the final product is ready, the courier service is notified and asked to pick up the package from the craftsperson’s site. If the craftsperson is not able to do the packaging, the packaging vendor is notified when the product is ready for packaging. After packaging and final quality inspection is done by the quality people, the goods are ready for dispatch and are then picked up by the courier people and dispatched to the customers.

Fig. 23.1.2

When the site goes in for an e-commerce set-up, the basic architecture will be as shown in Figure 23.1.2. When a customer shopping for handicrafts on the Internet orders an item online using a credit card, the processes that take place are as follows:

- Ordering: The customer enters the credit card details. She is presented with a summary of the items, price and billing information.

- Initiating the transaction: Encrypted payment information, secured with industrial strength encryption, is then forwarded to the merchant CyberCash cash register.

- Merchant picks up information: The merchant’s Internet storefront receives the encrypted payment message. The merchant’s identification information is automatically added. The customer’s credit card number remains invisible to the merchant.

- Through the CyberCash firewall: Still encrypted, the payment request is forwarded over the Internet and is received through a secure firewall by the CyberCash servers.

- From the cyber register to the bank: CyberCash instantaneously passes the payment request to the merchant’s financial institution or a third-party processor acting on behalf of the financial institution.

- From the cash register to the bank: The request for authorization is approved or declined by the consumer’s credit card bank or issuing financial institution.

- The bank sends approval: The response of the customer’s credit card bank or financial institution is returned to the merchant’s financial institution or the third-party processor. The response is returned to the merchant via the CyberCash cash register.

- Transaction complete and captured: The handicrafts product is delivered to the customer.

The costs associated with this transaction are as follows:

- The service provider’s set-up costs for a medium transaction site will be around Rs 20,000 per year

- Charges per transaction will depend on the type of credit card and vary from 2 to 3.5 per cent per transaction

A digital certificate costs around Rs. 10,000 to a few lacs, depending on the type of authenticity. To obtain it, one has to approach some valid parties such as CyberCash and VeriSign.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Explain the logistics system for online business store.

- How does the logistics system for online stores differ from the traditional method?

- What are the major issues in logistics for e-commerce trade?

Case 23.2

PHANTOM GLASS LTD.*

Seeking Solution to Curb Wasteful Warehousing Practices

In the year-ending review meeting called by Anil Jhunzunwala, MD, on 15 April 2001, Mahesh Pra-shad, General Manager, in charge of logistics, was pulled up by Ms Priyanka Agarwal, VP (Finance), who expressed her concern over the increased level of finished goods inventory that was creating cash flow problems. She also made remarks on the prevailing warehouse practices in the company, which were resulting in low productivity and higher warehousing cost. In defence, Mahesh Prashad tried to explain the situation based on the facts and figures he had with him and suggested some measures to overcome the problem.

The Company

Phantom Glass Ltd. is one of the leading glass manufacturing companies in India having an installed capacity of 32 million CSQM (600 tonnes per day) of float glass. The plant is located in western India at a prime location. The company is manufacturing a variety of international quality glass in technical and financial collaboration with a world-class manufacturer. The capacity utilization was 80 per cent during the last two years. This is much above the other producers of similar products in India. Phantom is making good headway in the market as the products are well accepted because of the world-class quality, and the prices are comparable to other available products in the market. Even in the prevailing recessionary trends in the market, the company registered an increase of 9.3 per cent in sales, similar to what they achieved last year, with the help of which they could maintain their market share at 20 per cent. The financial results for the past four years are shown in Table 23.2.1.

Table 23.2.1 Financial Result of the Period 1997–2001

Of the total production, 35 per cent is of premium quality glass used in the automobile sector, while the balance 65 per cent goes into other applications. Phantom’s 30 per cent sales are generated through exports.

The organization is headed by the Managing Director, assisted by the Vice Presidents, who head the technical, production, marketing, finance and material and logistics operations respectively.

The company is marketing its products through a network of four regional offices and 200 dealers. They have no material storage facilities at the regional level. The material after loading on to the carrier is unloaded at the customer’s or the dealer’s place. All domestic supplies are organized through road carriers.

Fig. 23.2.1 Organizational chart of phantom glass limited

Manufacturing Process

The main components of glass are silica sand (73–75 per cent), soda ash, magnesium and feldspar, which are weighed and mixed in batches, to which recycled glass (called cullet) is added in the proportion of 3:1. Cullet acts as a catalyst and thus reduces the consumption of natural gas that is used as fuel in the glass-melting furnace. The materials are tested and stored for mixing under computer control.

The batched raw materials pass from a mixing silo to the furnace, where they are melted at 1700°C. The molten glass is floated on to a bath of molten tin, which is less viscous than the glass and they do not mix with each other. This is done at 1000°C. The contact surface is perfect flat and the glass is in solid form.

After leaving the tin bath chamber, the glass in hard sheet form is passed through annealing chamber at 600°C. The hard glass sheets now pass over the roller. The annealing process helps in modifying the internal structure of glass and relieves it of internal stresses, enabling it to be cut and exhibit the desired physical properties. The glass surfaces from both sides are perfectly flat and need no grinding or polishing.

After cooling the glass sheets undergo rigorous quality checks and are then washed and sent to cutting section. The cut glass sheets are packed in wooden crates and stored for further dispatch to the customers.

Fig. 23.2.2 Glass manufacturing process

The Product

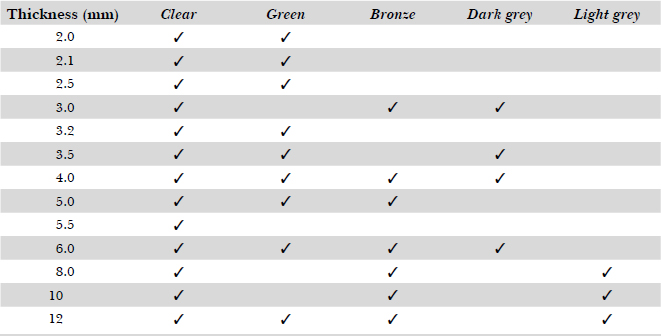

Phantom manufactures glass sheets in five different shades and thicknesses for a variety of applications. The sheets are cut according to customer requirements up to a maximum size of 9 ft × 16 feet. However, the most common size is 4 ft × 8 ft (see Table 23.2.2).

Table 23.2.2 Range of Glass Manufactured at Phantom Glass Limited

The major features of Phantom products are distortion-free and sparkling surface, thickness uniformity, high optical clarity, brilliant images when mirrored and higher strength for handling and usage. The product applications cover window glazing, curtain walls, partition walls, doors, shop fronts, furniture, mirrors, safety glass for automobiles, clocks, and so forth.

Logistics Operations

The logistics operations of PGL are handled by the General Manager, Mahesh Prashad, who reports to VP (materials and logistics). The customer service department (CSD) is under the GM—Marketing, who acts in close coordination with the logistics department (see Figure 23.2.3).

The customer requirements are conveyed to the logistics section by the CSD well in advance. Based on customer orders, the logistics section initiates the dispatch action. The flow chart in Figure 23.2.4 indicates the activities undertaken by the logistics department.

- Coordination with CSD The logistics department acts on the instructions of the CSD for material dispatches and maintains close coordination with them. However, due to delays in getting information on production schedules, the CSD department sometimes cannot give confirmed dispatch schedules to logistics. This results in part loading of the trucks, longer waiting for trucks (thus attracting the penalty), delays in loading and improper utilization of contract labour that are paid on a daily basis.

Fig 23.2.3 Reporting structure in the logistics department

- Load unitization in crates The glass sheets cut into various sizes are unitized in wooden crates. Phantom uses over 100 different sizes of crates for the customized requirement of glass sheet sizes by the customers. They use 10,000 crates per month. However, out of the total crate requirement, 30 per cent fall in size 8 ft × 4 ft, 20–25 per cent in sizes 16 ft × 9 ft and 10 ft X 8 ft, which is reserved for exports. The balance 50 per cent requirement of crates is in odd sizes (see Table 23.2.3).

The packaging cost for the domestic consignment is 8 per cent (due to the large number of odd sizes) of the product cost, while it is 5 per cent of the product cost for the export consignment.

- Allocate the storage space After the glass sheets are packed, the crates are moved to the warehouse for space allocation and storage. The area available for storing the finished goods is 2500 sq metre. The warehouse bay has two overhead cranes of 10 MT capacity each and two forklift trucks of 500 and 1000 capacity respectively. The crates are stored in the vertical inclined position. They have special ‘A’ type racks to keep the crates in the vertical inclined position at 95 degrees.

Table 23.2.3 Packaging Details of Phantom Glass Limited

Fig. 23.2.4 Material flowchart at logistics department

Fig. 23.2.5 Stacking arrangement of crates

These racks (600 no.) occupy more than 250 sq metre of floor area. As the product is stored in packed form in the crates, the area required for storage is almost 30 per cent more than for bare glass sheets. Due to space constraints in the warehouse, they store 250 CSQM of material per sq metre of warehouse floor space, while the international standard for easy and safe material (glass) storage and movement is 175 CSQM per sq metre of warehouse floor area. Due to legal constraints and the fragile nature of the product, they cannot plan for a multi-storey warehouse building. The order picking operation takes a lot of time due to the over-storage at warehouse. A lot of time is spent in removing the other crates to locate the right material and clear the movement path for the forklift. The breakage rate during material handling in warehouse area is on the higher side due to the congested storage arrangement.

- Organize the dispatches The logistics department is also involved in dispatch of the material from factory to various clients. The dispatch instructions are issued by the CSD. The contract labour are used for material movement and loading. The material is dispatched to customers and dealers through road carriers. The material is normally dispatched through tempos (6 tonnes), trucks (9 tonnes) and trailers (25 tonnes).

For the exports consignments, they use 20 ft dry, box-type containers. The material is loaded with the special ‘C’ type clamp developed for easy loading of the glass sheet crates inside the container. Due to lack of coordination between the CSD and the logistics departments, the trucks and the container trailers keep waiting for 2/3 days. The waiting attracts a penalty of Rs. 1000 for a container trailer and Rs. 500 for a lorry per day.

The productivity level at the logistics department is very low. In spite of engaging contract workers, they make 2/3 loads per shift as against the norm of 5 loads. They engage 5/6 groups per day to make the loads. Each group consists of five labourers and one supervisor.

On an average they dispatch 360–400 tonnes of material per day using a combination of the following vehicles:

25-tonne trailer

10–12 no.

9-tonne truck

8–12 no.

6-tonne LCV

10–15 no.

- Inventory management Inventory management is an integral part of the job responsibility of the warehouse manager. The stock control is manual. The warehouse staff spends much of their time in multiple manual entries. Without bar coding system, the material storage and retrieval takes a lot of time. Material tracking is a tedious task. The warehouse maintains an inventory of over 200 odd sizes (combination of thicknesses, sheet size and colours). Phantom’s marketing policy allows them to supply the material in customized sizes, which contributes to more than the 50 per cent of the company’s sales. The major problem is the inventory of the odd sizes, which at any point of time has more than 60 per cent of the share in value terms. The inventory movement observed during the past 12 months is shown in Table 23.2.4.

Table 23.2.4 Inventary Movement of the Last 12 Months at Phantom Glass Limited

Note: 1CSQM = 4.85 kg

The inventory turnover ratio at Phantom is 3.8, which is quite low as compared to the international standard that is in the range of 6–7.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- To bring down the inventory-carrying cost, which includes the carrying cost for packaging material, would you suggest the storage of glass sheets in an unpacked condition and packaging only at the time of dispatch? Discuss the new system in light of the problems they may face.

- What measures would you suggest to Phantom to reduce the inventory level?

- In light of the storage density they are presently having, is this a case for additional warehousing space? Justify.

- How will you organize the logistics activity at Phantom for improvement in the productivity, effectiveness and efficiency of the logistics department?

Case 23.3

N-JOY TOBACCO COMPANY*

Aiming at Best Practices in Distribution

“Smoking is injurious to health”—a warning punch line, the statutory requirement that all tobacco manufacturers should print on all tobacco products leaving their factory. The warning is not deterring the smokers as is seen from the increasing consumption of cigarettes in the country. India is the second largest smoking market in the world consuming 950 billion sticks per year. The products include biddies, cigarettes, cigar, cheroot, and so on. Among the cigarette smoking countries in the world, India ranks eighth, consuming 102 billion cigarettes per year. The cigarette industry in the country is growing at the rate of 3.5 per cent per year.

An interesting feature of the cigarette industry is the presence of a wide array of brands. There are four major manufacturers of the product in the country. The Indian cigarette industry is marketing over 160 brands across the country. Out of the 160 brands, 45 brands come from N-Joy Tobacco Company (NTC) Ltd., which is one of the leading manufacturers of cigarettes in the country. These 45 brands together constitute a wide product spectrum offering varied prices, quality and sophistication to suit the different tastes and income levels of multitudes of cigarette users. NTC has a sales turnover of over INR 50,000 million and commands nearly 50 per cent of the cigarette market in the country. NTC is facing stiff competition in all the market segments. The management of the company believes that the survival of the company depends on brand management supported by an effective, efficient and innovative distribution chain. For gaining a competitive edge over their rivals, the management has identified three goals for the distribution supply chain:

- To make available 45 stock-keeping units (SKUs) at the 1 million retail outlets to reach 50 million smokers.

- To ensure freshness of stocks—product shelf life 2 months.

- Operating a cost-effective logistics supply chain through the proper management of critical cost elements such as inventory, freight and warehousing.

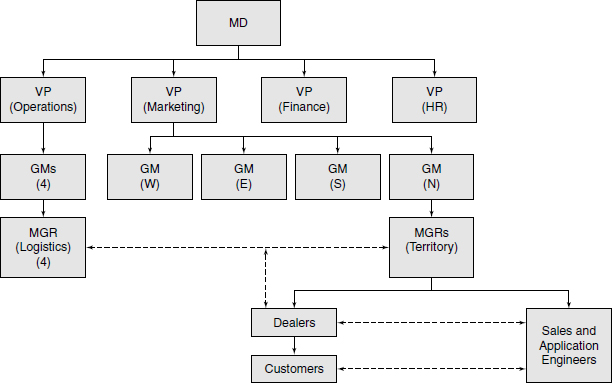

NTC currently has four factories of their own. In addition, they subcontract production to five other parties. Besides their own network of marketing offices, they service the clients through their wholesalers and retailers. The movement of goods from the factories to the ultimate consumer is explained in Figure 23.3.1.

NTC provides services to its consumers through a network consisting of its own marketing offices, which control the channel members, such as wholesale dealers, wholesalers and the retailers.

Marketing set-up

Regions—4 Regional Managers

Branches—20 Branch Managers

Fig. 23.3.1 Distribution diagram of the movement of goods

Circles—80 Area Sales Managers

Sections—180 Area Sales Executives

Dealers

NTC is having over 750 exclusive dealers spread over the country, who only deal in NTC products. They get the material from the C&F godowns as per the instructions of the branch office they are covered by. As the percentage commission on the sales is very low in the cigarette industry, these dealers work on sales volumes. They control a number of wholesalers in the region in which they operate. The exclusive dealers own a fleet of delivery vans for distributing the products to the wholesalers. These dealers also maintain a team of cycle salesmen who directly interact with retailers for getting orders, organizing supplies and collecting payments. Sixty per cent of the supplies are made through the cycle salesmen directly to the retailers and the balance 40 per cent through the vans to wholesalers.

Wholesalers

Wholesalers get their materials from the NTC dealer through the dealer’s vans. They supply the goods to the retailers twice a day through three or four wheelers. The van driver acts as the salesman and payment collector. The material is supplied against cash payment and no credit is offered to the retailers. The investment capacity of the wholesaler is 10–20 days. To control freight the focus is on distribution route planning. On an average the van salesmen make 4 million calls per annum to attend the retailers.

Retailers

They are the last link of the distribution channel and number over 10 million. Retailers generally have an investment capacity of 1 or 2 days. The requirement is small, but need high frequency supplies. They are attended by 8000 cycle salesmen and 1000 supervisors making 84 million sales calls and 6 million merchandizing and supervising calls per year.

The Marketing and Manufacturing Interface

The role of the branch offices is crucial in the coordination of field requirement with factory supplies. In the distribution chain, the dealers place the order on the branch office. The dealer gets the requirements both from the wholesalers and retailers. The branch office consolidates the dealer’s requirements, which is conveyed to HO (marketing) for all India consolidation in order to prepare the raw material procurement plan and the manufacturing schedules. The branch office draws the requirements from the factory.

Fig. 23.3.2 Manufacturing and marketing interface

Measures to Control

For managing 94 million calls per year, the NTL logistics manager proposes the following measures to manage the supply chain so as to reduce the logistics cost as a percentage of sales from 2.3 to 1.8 per cent.

- Sales Forecasting

- The expected forecasting accuracy ± 2 per cent (the variation of ±5 per cent in forecasting results in stockpile or stock depletion equivalent to the capacity of a small factory leading to high carrying cost or lost market)

- Bottom-up forecasting

- Develop forecasting model

- Funds Management

- No credit sales

- Open more collection centres

- Encourage dealers/wholesalers to have a higher stock-turnover ratio for higher ROI, instead of increasing the commission

- Collection responsibility on the wholesaler only

- Inventory Management

- Excise on cigarette is 60%. Hence, post-excise inventory (i.e., in-transit/pipeline) of minimum 4 days

- The inventory at factory before excise: 6 days

- Stocks with channel members (wholesalers): 6 days

- Factory should produce and dispatch strictly as per the branch orders

- Inventory and forecast review once a week

- Branches to directly order on factories

- Zero time lag between forecasting and ordering

- Transportation Management

- No delays: as a delay of one day in transit time costs INR 30 million as interest cost

- Daily interest cost on one truckload of material Rs. 3500

- Long route coverage and no transhipments

- Transit time bonus/penalty for transport contractors

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Do you agree with the proposals of the logistics manager? If yes, what resources are required to implement the suggestions?

- Do you suggest any model for controlling the inventory?

- Do you agree that NTC should engage the services of a third-party service provider to bring effectiveness and efficiency in the system?

- How will you plan and implement the logistics programmes for meeting the requirements of the channel members?

- For effectively controlling the supply chain of NTC, do you foresee any limitations in planning and implementation of the information flow system?

Case 23.4

JOLLY SNACK FOOD PRODUCTS COMPANY*

A Case for Freight Rationalization

Snack food market in India is growing at 25–30 per cent per year. This is what the organized sector believes. The unorganized sector dominates nearly 50 per cent of the market. The local players sell both branded and unbranded products that are 20–25 per cent cheaper than the national brands. The unbranded products are supplied to small- and medium-sized restaurants, bars, clubs and pubs in bulk quantity. However, the branded products are popular among the educated elite and the young generation in urban areas. Due to the changing trends in lifestyle and adoption of western culture, food habits among Indian youths are showing a change. As a result, there is more inclination towards fun and enjoyment in life, which is reflected in food habits and living style of the younger Indian population, both in urban and semi-urban areas.

Company Background

Based on the market survey conducted in 1987 by Jolly Food Products Co. (JSFPC), a subsidiary of the multinational company set up a snack food plant at Patiala and Delhi to manufacture potato chips, baked cheese, fried pallets, and so on. Their mission is “to be people’s favourite snacks and be always available when required.” In the demanding market scenario, where staying ahead of the competition is a key challenge, the pace with which one responds is of strategic importance. With volatile demand, today the emphasis is on “make to sell rather than make to stock.” With high consumer expectations and the need for rapid response in marketing, distribution assumes more significance and provides the required competitive edge. Availability of material and products at the right time and place has become a prerequisite for creating long-term loyalty.

The market survey conducted by JSFPC, through country’s leading market research agency, on consumer perception indicates over 95 per cent customer satisfaction. The three product varieties introduced so far hit the markets and increased the bottom line of the company. But due to competition from the unorganized sector on the price front, Randeep Singh, GM (marketing) is worried about the distribution cost as a percentage of the product cost, which has been growing over the years and reducing the profit margin. On the other hand, due to cut-throat competition JSFPC is under tremendous pressure to keep prices at a level acceptable to the customers.

Problem Analysis

To analyze the distribution cost problem, Randeep Singh assigned the job to Lobo, an engineer MBA with four years of experience in the distribution of FMCG products, who joined JSFPC as logistics manager. He is with the company for the last one month. Lobo took it as challenge to show his worth to the company. He studied the current JSFPC distribution system that is reflected in the distribution chain shown in Figure 23.4.1.

Fig. 23.4.1 JSFPC distribution chain

JSFPC’s first phase of distribution from the factories to the C&F agents is more critical as it involves the long-distance freight-paid dispatches, with primary freight charges included in the maximum retail price (MRP). The distribution of the product from the C&F agent down to the retailer is taken care of by the channel members. The freight charges for secondary transportation from C&F agents down the line are taken care of by the channel members, who are compensated through commissions and quantity discounts. As the products are sent through open trucks, JSFPC encounters the following problems:

Transhipments

Due to the minimal weight requirements, the transporter sometimes clubs some other heavy goods with JSFPC products, resulting in transit damages. The trucks are sometimes not loaded to volume capacity because of varying product mix requirements.

Freight

JSFPC products occupy more space and hence the 9-tonne truck is underutilized in terms of the weight factor, resulting in higher freight charges per unit weight.

Damages

Transit damages in the open trucks is to the extent of 8–10 per cent due to improper handling, transhipments, protrusions, mixing with other cargo (no control over the transporter once a vehicle leaves the factory).

Pilferage

JSFPC have sometimes received complaints from C&F agents about short supplies, which usually occur due to pilferage of this tempting food product. The percentage is not so alarming but JSFPC wants to eliminate this.

JSFPC is packing the products in transparent plastic bags of 200 grams each. These bags are packed in cartons of average size 2 ft × 1 ft × 1 ft. The average dispatches of three stock keeping units (SKUs) during the last twelve months were:

SKU “A”—68 per cent

SKU “B”—25 per

cent SKU “C”—7 per cent

Proposed Solution

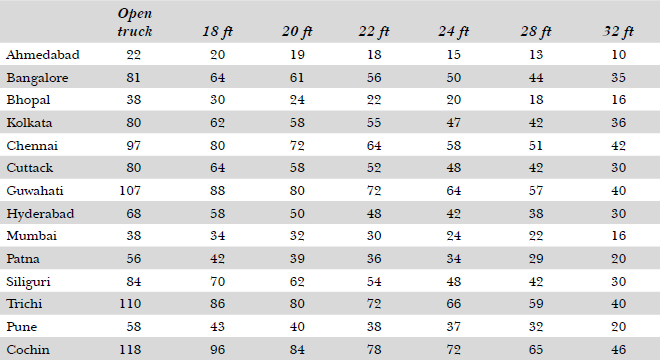

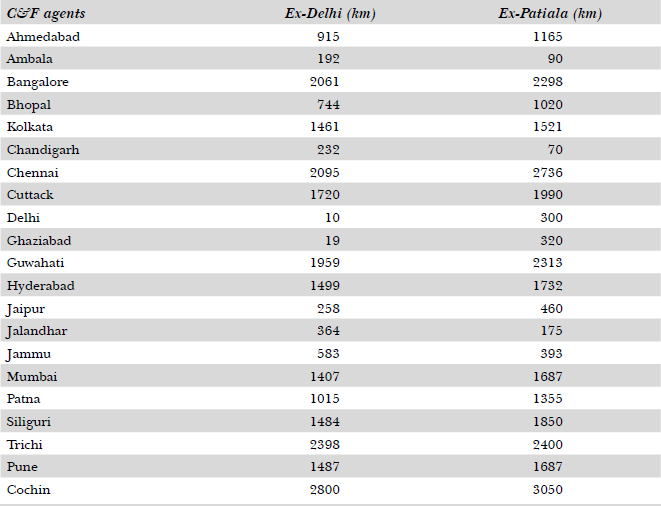

To get over the present problem, Lobo considered using closed containers for dispatch of the material from the factory to the C&F agents. He thought the closed box container would be the safer, faster and cheaper method of dispatching the material. JSFPC could enter into a contract with the transporter for container shipment on a long-term basis at the lowest cost. Logo first decided to compare the freight of open truck (9 tonnes) with the various sizes of the containers on the following basis:

- Rs per km

- Rs per cu ft

- Rs per kg

- Rs per case

The comparison of cases fitting into the open truck and the various sizes of containers is presented in Table 23.4.1:

Table 23.4.1 Container Size and Cases Occupancy

The major task before Lobo was to find out the optimum size of the container in place of the open truck. Once this exercise was over, the C&F agent’s base could be further enlarged. The freight economy with the reduction in transit damages and pilferages would ensure a lot of savings that will enhance the margins and may help in reviewing the MRP to face competition. Lobo worked out the freight for each of the above container sizes on per km, per kg, per cu ft and per case basis, the results are presented in Tables 23.4.2–23.4.9.

Table 23.4.2 Freight Ex-Delhi Rs per km

Table 23.4.3 Freight Ex-Delhi Rs per kg

Table 23.4.4 Freight Ex-Delhi Rs per cu ft

Table 23.4.5 Freight Ex-Delhi Rs per Case

Table 23.4.6 Freight Ex-Patiala Rs per km

Table 23.4.7 Freight Ex-Patiala Rs per kg

Table 23.4.8 Freight Ex-Patiala Rs per cu ft

Table 23.4.9 Freight Ex-Patiala Rs per Case

Table 23.4.10 Geographical Distances Between Factories and C&F Agents

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Which of the following is the most appropriate basis to assess freight charges for snack food products?

- tonnage

- volume

- cases

- kilometre

- Do you agree with Lobo’s approach to evaluate the problem?

- What are the other options that Lobo has for freight reduction?

Case 23.5

KAPIL HEALTH FOOD PRODUCTS*

Mapping the Supply Chain for Weak Linkages

A recent survey conducted by a leading Indian business magazine shows that health food products is one of the fastest growing industries in India. It is growing at 15–18 per cent per annum. The growing health consciousness among the educated families, particularly in the urban areas, is contributing to the growth of health food requirements. The health food concept is not new to India. Traditionally, educated mothers conscious about the health of their growing children fed them milk mixed with dry fruits or Chavan Prash (an Ayurvedic preparation) once or twice a day. However, during the past three decades the health drink companies have succeeded in convincing the mothers to switch over to ready-to-make food drinks for their school-going children. Branded products such as Horlicks, Bournvita, Maltova and Protinex, earlier recommended by doctors and used for ailing patients for speedy recovery of their health, now occupy the kitchen shelves. Due to the changing food habits and growing health consciousness among educated youth (both male and female), the consumption of the branded food drinks is growing every year. The total market for health food is estimated at 60,000 tonnes.

Company

Kapil Health Food Products was established in 1960 as a subsidiary of an American multinational pharmaceutical company with total capital outlay of INR 50 million. It started its manufacturing operations at Nahar, which is situated 325 kilometres west of New Delhi. The place is now well developed and has a population of 8500. It is located 800 metres above the sea level and witnesses a temperature variation of 5 to 47°C during the year. Nahar is a semi-urban town supported by the village’s economy. In 1980 the foreign holding of the company was diluted to 51 per cent with 49 per cent shares offered to Indian nationals and financial institutions. The company got registered as Kapil Health Food Products Ltd. As milk is the major raw material for the firm’s products, their major focus is on dairy development activities. They undertake programs such as animal health, animal nutrition, farmer development, animal breeding, animal insurance, mechanized milking, and so on. The company spends around INR 750 million per annum on the above-mentioned activities.

The operations at Nahar are managed by 20 managers, 60 executives, 120 staff, and 900 fulltime and 600 contract workers.

KHFL is a continuous success story since its inception in 1960. It is now a leading health food manufacturing company contributing 32 per cent of the total health food powder production in India. The major competition is from leading brands such as Bournvita, Boost, Horlicks and Nu-tramul Maltova. The company faces indirect competition from the health drink preparations of the Ayurvedic pharmaceutical companies in India. All together, they command around 10–12 per cent of the health food market in India.

Table 23.5.1 KHFL Success Story

| Parameters | 1960 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|

| Production capacity (1000 tonnes) |

2 |

35 |

| No of units | 1 |

4 |

| Factory area (sq yards) | 40,000 |

75,000 |

| No. of product lines | 1 |

14 |

| Manpower employed | 50 |

1700 (600 casuals) |

| Milk processed (litres/day) | 7000 |

1,50,000 |

KHFL is an ISO 9002 accredited manufacturing firm with a state-of-the-art manufacturing and packaging facility. The key equipments include the pilot spray drier with the latest technology and the automatic packaging line. They have an excellent environmental management system that includes an effluent treatment plant and eco plantation.

Products

KHFL runs three product lines—two for health foods (HOR and BOS) and the third for ghee. The company also supplies the products in bulk to the various repacking stations across the country to take advantage of freight economy. The following are the common sizes for product packaging (see Table 23.5.2).

Table 23.5.2 Product packaging at Kapil Health Food Products

| HOR | BOS | Ghee |

|---|---|---|

| 500 g | 500 g | 500 g, 1000 g |

| 1000 g | 2000 g, 5000 g 10,000 g |

The products are packed in polythene bags, corrugated paper boxes, cartons and tin containers. The company started automated packaging operation in 1995 using state-of-the-art machinery from Germany with a capacity of 60 packs per minute and capable of handling 200–1250 gram pack sizes.

Procurement

KHFL has a full-fledged procurement department headed by the procurement manager, who is assisted by a team of four purchase officers. The firm has developed its own software for material requirement planning. Since the number of raw materials handled is restricted to six, the management has good control on the inventory and the suppliers. Except milk, which is the major raw material, for all the other raw materials, the firm has restricted its supplier base to four to five selected vendors. The firm is very particular about the quality of ingredients going into its final products, and hence the vendor selection criteria are very scientific and conform to the ISO requirements. The firm banks on the reliability and consistency in raw material quality and delivery.

Table 23.5.3 Major Raw Materials Consumption (MT/day)

| Wheat Flour | 28 |

| Malted Barley | 26 |

| Malt Extract | 35 |

| Sugar | 8 |

| Milk Powder | 14 |

| Liquid Milk (litres) | 1,50,000 |

Packaging consumption (units per day) is 1800 tin containers, 250 cartons and 435 polythene bags. The total number of truck arrivals at the Nahar plant is 35 per day. The transportation cost is borne by the company.

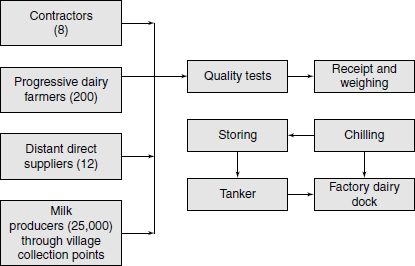

The milk procurement is done within 55 kilometres of the area around the Nahar plant from 25,0 milk producers, 200 dairy farmers and 20 contractors and distant suppliers.

Fig. 23.5.1 Milk flow

Manufacturing Process

The process starts with mixing of malted barley and wheat flour. The mixture is washed, sieved for husk removal and finally squeezed. The squeezed mixture is then mixed with milk, oily vitamins, malt extract and other ingredients. It is further evaporated in two stages, oven dried, and undergoes a food scalping process. The mixture is mixed with sugar and further undergoes grinding and final mixing. The final product is health food in granular form that is taken to the bulk packaging section for quality clearance, and is afterwards stored in the warehouse. The bulk packages are sent to packing stations for making small packs as described before.

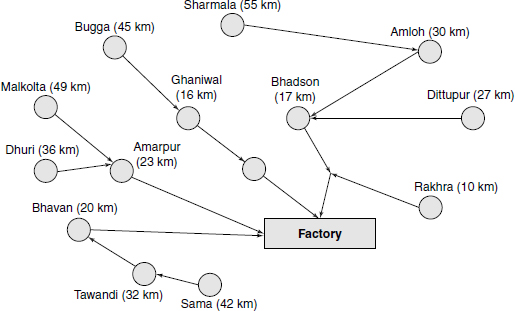

Fig. 23.5.2 Milk collection centres

Fig. 23.5.3 Manufacturing process

With few modifications and without major investment, the present installed processing capacity can be increased by an additional 30 per cent. This increased capacity will enable them to take care of the upcoming requirements in the next two years; provided the market share is maintained at the level of 60 per cent.

Finished Products Dispatches

They produced 35 kilo tonnes of finished products in 2001 averaging 100 MT per day. In the total production, health food contributes 95 per cent by weight and the balance 10 per cent is contributed by ghee. The break-up in terms of bulk and flexible packs is presented in Table 23.5.4.

Table 23.5.4 Packaging Sizes of Kapil’s Finished Products

| Bulk pack (drums/day) |

Flexible packs (dozens/day) |

|

|---|---|---|

| HOR | 270 |

1800 (500 g) 1450 (1000 g) |

| BOS | 170 |

1650 (500 g) |

| Total | 440 (13 trucks/day) |

4900 (5 trucks/day) |

Marketing Arrangement

KHFL is marketing its products through the dealer network. The firm has four regional offices at all the major metros headed by the regional managers, who report to the general manager (marketing) sitting at the Delhi head office. The regional managers are responsible for the sales administration, C&F agents, stockiest and wholesaler network in the region. Currently, KHFL has a network of 8 C&F agents, 45 stockists and 200 wholesalers. The products are sold through all grocery and pharma shops. The product requirement flows from wholesalers to the stockist to the regional office, which directs C&F agents for organizing dispatches. The regional offices prepare the forecast, which is forwarded to the factory for manufacture and execution. The replenishment at C&F warehouse is done as per the requirement of the regional office and the consumption pattern in the region. KHFL maintains 15/18 days stock of finished goods at the factory warehouse, 12/15 days at C&F agents and 8/10 days with stockists and 7/8 days with wholesales. Currently the order-filling rate at C&F warehouse is 89 per cent. Wholesalers are unable to fulfil two orders in every twenty orders placed by the retailers. The regional offices and C&F agents are connected online through VSAT. Due to the severe competition in markets, KHFP is in the process of reviewing its supply chain for cost reduction and enhancing its customer service. The management is planning to reduce the inventory to less than 10 days at factory and at C&F agents. The distribution cost at the present level of sales is 8.5 per cent, which they want to reduce by 40 per cent. In addition, they would like to reduce the inbound transportation cost through proper planning and scheduling.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Map the supply chain of KHFL for weak linkages.

- For improvements in critical areas in the KHFL supply chain, what measures do you suggest to reduce cost and improve customer service?

- The major cost-spinner in KHFL logistics operation is inbound transportation. Do you agree with this? How can it be reduced?

Case 23.6

PRIYA NAMAK COMPANY*

Revamping the Distribution Structure

The case of Priya Namak Company (PNC) deals with the distribution and packaging decision at multiple demand points of iodized salt. The supply is done from the source plant located on the west coast of Gujarat. At Priya Namak common salt is extracted from seawater through the natural evaporation process using sun heat. The whole process spans over a few months. The solid whitish material that settles after evaporation is common salt in crude form. It is processed for removing the impurities and further treated to bring the iodine content at the desired level. The finished product is called iodized salt, meant for human consumption. Iodized salt is a low-priced daily consumption product used in food preparation.

Iodine is used by the body to form thyroxin, an essential hormone. Salt is used as a medium for supply of iodine to the body. Because of the requirements of the thyroid gland and to reduce the incidence of goitre (an iodine-deficiency disease), a normal person needs about 75 mg of iodine per year. The country is now producing an estimated eight million tonnes of salt per annum, out of which three million tonnes (expected to rise to 10 million tones in the near future) is consumed by the industry. Of the total edible salt market, 75 per cent is served by unbranded products, 23 per cent by branded salt and the balance 2 per cent by specialized edible salt varieties. Out of the total packed salt around 55 per cent is accounted for by the large brands, and the balance 45 per cent of the market comprises of small local brands. Typically, the average salt consumption of a human being is 11–18 grams per day. Now, one can easily guess the bright future for manufacturers of iodized salt, considering the fast growing population and the consequent need for satisfying its salt requirement.

Priya Namak is the largest and the most integrated salt works complex in the country, generating over 2 million tonnes (p.a.) of solar salt. The company also manufactures a variety of chemicals for which the major raw material is salt. After the washing, sieving, grinding, evaporating and chemical treatment, the finished product obtained is iodized salt. Currently, Priya Namak is producing 1200 tonnes of vacuum-evaporated iodized salt per day and 2000 tonnes of other chemical products. The salt works and the processing plant are spread over 2500 and 650 acres of land respectively.

The company has a projects division comprising the research and development department, helped by a mechanical and detailed engineering department. Forming the backbone of its research-based operational policy, it has a computer-aided research, design, engineering and management centre equipped with pilot plant facilities, advanced computing facilities and a host of state-of-the-art software. The division is capable of carrying out plan simulations, basic engineering, project monitoring, planning and scheduling in all the disciplines.

The process equipment division of the company comprises a foundry, a workshop and control facilities. It has shops for melting and moulding, a fettling shop, a pattern shop, a machine shop, a fabrication shop, a heat-treatment facility and a testing and quality control cell. It is capable of manufacturing static equipment, seawater pumps and process pumps ranging from carbon steel, stainless steel and grey cast iron to titanium.

The engineering division comprises the construction, electrical engineering, instrumentation and maintenance departments. Equipped with a variety of facilities, it is capable of carrying out construction-related activities, including the building of heavy foundations, structural work, erection of plant and machinery (including boilers and turbo-generators) and the installation and commissioning of electrical, instrumentation and control systems disciplines.

For salt, Priya is one of the leading companies in the iodized salt segment with a considerably good market share compared to its national competitors.

Table 23.6.1

| Manufacturer | Market Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Priya | 36 |

| Brand A | 28 |

| Brand B | 12 |

| Others | 24 |

Priya had sales of about INR 150 crores in 2001 and exported 12,000 tonnes of iodized salt to the Middle East and East Asian countries. Priya is selling its “Priya—Common” iodized salt at Rs 7 per kg and planning to bring out a low-end brand “Priya—Janata” at Rs. 5 for the low-end market to convert the users of loose salt to the branded and packaged salt product.

Fig. 23.6.1 Distribution channel for Priya namak

Priya is currently operating through a single marketing agency that reaches the consumers through a network of 30 distributor-cum-C&F (carrying and forwarding) agents, 2500 stockists and 1,00,000 retailers. Priya was earlier doing the entire retail-packaging job at their Gujarat plant, which has now been shifted to field packaging at the C&F’s place. The company now dispatches the material in bulk through railways to the C&F agents in 50 kg bags in trainloads to economize on freight. On an average, each C&F agent procures 2000–2500 tonnes of iodized salt from Priya per month. Salt being an essential commodity, the demand for it does not fluctuate too much. However, each C&F agent keeps a safety stock of 50 tonnes, The C&F agent supplies the products to stockists in the required pack sizes of 500 g, 1 kg, 5 kg, and so on. The packaging is done according to the hygiene norms set by Priya. Depending on the sales volumes, Priya has appointed 30 packaging partners as C&F agents, with varying packaging capacity, all over the country. Salt in bulk is supplied to the packaging partner-cum-C&F agent as per the requirements of distributors, who in turn get their requirement from the stockist who is in touch with the retailers. Because of low unit price of the product, the logistics cost of salt distribution is to the tune of 54 per cent of the product-selling price. This means that for the one-kilogram salt pack selling for Rs. 7, the logistics cost works out to Rs. 4.05 per kg.

According to the ORG-MARG retail store survey for April 2002, the size of the iodized branded salt market is 15 lakh tonnes per annum; valued in monetary terms at about Rs 700 crores. Iodized branded salt market is estimated to grow at 20 per cent per annum. The market share of the national brands and the local brands in the iodized salt segment is 70 per cent and 30 per cent respectively. Priya continues to reap the early bird advantage, having 36 per cent share of the national branded salt segment. Due to an effective iodine-deficiency campaign, the penetration of branded iodized salt is about 20 per cent nationally. Even though manufacturers are trying to differentiate through attributes such as “iodized,” “granular,” “free flow,” and “vacuum evaporation” to influence the customer, the consumer preferences are for reputed brands and familiar names like Priya. The salt is a habitual product and the consumer does not prefer frequent brand switches. The housewife looks for the comfort level and the measure of salt. The outcome of the research, conducted by a leading market research organization in the country, is that the Indian consumer is willing to switch among a set of preferred brands, depending on the availability, personal preference and product offering. Similar to other FMCG products, if a consumer gets a certain branded salt free with other purchases, the chances that s/he may continue using that brand are increased. Hence, the market offering and the distribution muscle are the keys to success in the iodized salt market. Priya penetrates urban, semi-urban and rural markets through economy pack sizes and forms and product development for newer and more evolved offerings. The nearest rival of Priya has shown an average increase in market share of one and half percent in the last five years. It has already reached 1500 towns and has a network of 1150 distributors. As against the field packaging strategy of Priya, the packaging for Brand B is done at the factory.

Due to the growing competition, Priya felt a need for reviewing its distribution system and appointed a consultant to review the exiting system and suggest improvement. The consultant indicated that Priya has no direct interaction with channel members leading to the poor information availability about the market. The consultant suggested reducing one channel layer in the distribution chain. The consultant further observed that the distributor-cum-C&F agency is a single entity affecting the distribution, leading to the high level of outstanding payment and longer cash cycle. Therefore, the distributor and C&F functions need to be separated and Priya should directly deal with distributors, opined the consultant. In addition, Priya should IT-enable its distributor chain. The consultants were of the opinion that this structural change would help Priya to have better control over the distribution channel, information availability and a more dynamic response to market conditions. Further, they were of the view that with the new arrangement, Priya would also have better controls on inventory and outstanding payments. This would help Priya to reduce working capital needs and corresponding interest cost leading to higher sales and market share.

The consultants further made a remark that to remain in the leading position, Priya should continuously review its value delivery system. The commodity market will progressively move into the branded portfolio as long as the value delivery is in line with the product price. The margins will continue to be thin till the consumer perception of the differentiated values that brand offer over commodity changes significantly.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Review the outbound logistics process at Priya.

- Though Priya has an advantage of being early bird in the iodized salt market, but the next rival is aggressive in bridging the gap in market shares. As distribution is the key element in this market, discuss the logistical strategies Priya should adopt to retain its present position.

- Review the consultant’s suggestions in light of their merits and demerits.

- Does Priya face any barriers in implementing the suggestions?

Case 23.7

CADBURY PRODUCTS*

Lean Supply Chain through Demand Management

Sugar confectionary has seen a transformation with the conventional chocolate Eclair complemented by a host of fruit-filled, soft-centred, coffee, cream and caramelized candies. Broadly, the entire confectionary market can be divided into seven major categories, namely hard boiled (HBC), toffees, éclairs, chewing gum, bubble gum, mint and lozenges. The entire confectionery market in India is estimated to be 80,000 tonnes in volume and INR 7 billion in value terms.

Fig. 23.7.1 Major categories of the confectionery market

The Indian chocolate market grew at the rate of10 per cent per annum in the 1970s and 1980s, mainly among the children segments. However, in the 1990s the industry witnessed a growth of 12 per cent. ORG-MARG estimates that the chocolate penetrated just about 5 per cent of the Indian households in 2000 as against sugar-boiled confectionary that reached 15 per cent of households. Even considering the urban market alone, this category reached just 22 per cent of the urban consumers. Of the total market, chocolate segment constitutes 22,500 tonnes, which is INR 400 crores and is dominated mainly by Cadbury and Nestle.

In the late 1980s when the market started stagnating, Cadbury repositioned its Dairy Milk to an “anytime product” rather than an “occasional luxury.” Its advertisement focused on adults rather than children. Cadbury’s Five Star, the first count chocolate was launched in 1968. Due to its resistance to temperature, the Five Star has become one of the most widely distributed chocolates in the country. Other competing brands, such as GCMMF’s Badam Bar and Nestlé’s Bar, have minor shares. In the early 1990s, high cocoa prices compelled manufacturers to raise product prices and reduce their advertisement budget affecting volumes significantly. The launch of the wafer Kit Kat and Perk spurred volume growth in the 1990s. These chocolates were positioned as snack food rather than on indulgence as a platform, compete with biscuits and wafers.

Chocolates in India are consumed as an indulgence and not as snack food.

The consumption of chocolate in India is extremely low compared to the foreign countries. In India it is around 160 g in urban areas compared to 8–10 kg in the developed countries. In the rural areas it is still less.

Cadbury, a subsidiary of Cadbury Schweppes, is a dominating player in the Indian chocolate market with brands like Dairy Milk, Five Star and Perk. Dairy Milk is in fact the largest selling chocolate brand in India. Chocolates contribute 64 per cent to the Cadbury sales turnover. The confectionery sales account for 12 per cent of the turnover. Cadbury is attempting to expand its confectionary product portfolio with the launch of sugar-based confectionary such as Googly and Fruitus. But it is not a success story. In malted health drink Cadbury has a strong brand Bournvita, which accounts for 43 per cent of the sales turnover.

Cadbury continues to dominate the chocolate market with about 70 per cent market share. Nestle has emerged as a significant competitor with about 20 per cent share. The key competition in chocolate is from Amul and Campco, besides a host of unorganized sector players. Cadbury enjoys 4 per cent market share in confectionary product segment, wherein the leading national players are Nutrine, Ravalgaon, Cadico, Parle’s, Joyco India and Perfetti. The MNCs such as Joyco and Perfetti have aggressively expanded their presence in the country in the last few years.

The malted drink category covers white and brown drink. White drink accounts for two-thirds of the 80,000-tonne market. The south and the east are the largest consuming regions in India for food drinks. Cadbury Bournvita is the leader in the brown drink (cocoa-based) segment. In the white drink segment SmithKline’s Horlicks is the leader. The other significant players are Heinz (Complan), Nestle (Milo), GCMMF’s (Nutramul) and other Smithkline brands (Boost, Maltova and Viva). Cadbury holds 14 per cent share in the health drink market.

Despite tough market conditions and increased competition, Cadbury managed to record 11 per cent top-line growth in 2000. The company achieved a volume growth of 5.2 per cent. This was achieved through innovative marketing strategies and focused advertising campaigns for the flagship brand Dairy Milk. The net profit of the company rose by 41.8 per cent to INR 520 million in 2000. The reduced material cost, effective and efficient logistics operations and tight controls on working capital enabled the company to grow. The company added 6 million consumers and saw the growth of its outlets to 4.5 lakhs and consumers to 60 million.

The Cadbury management has cut down on its growth target by setting a 10 per cent average volume growth for the next three years (as against 12 per cent growth in volume and 20 per cent in value earlier targeted). Coupled with inflationary price increases, this could translate into a top-line growth of 14–15 per cent. This target is also difficult to achieve due to consumer slowdown and the fact that company is dependent on a single category of chocolate to drive growth. In the malted food drinks category, the company faces stiff competition from Smith-Kline Beecham and market share is stagnant around 14 per cent despite company’s efforts and investments in repositioning the brand. Efforts at expanding the confectionery portfolio have also not yielded the desired results. The management has declared its intension to focus on Éclairs in this category for the time being. In chocolate the onus is on 2–3 brands, which have supported growth in the past. Cadbury dominates the Indian chocolate market with 70 per cent market share.

Table 23.7.1 Product Categorywise Contribution to Cadbury’s Scales

| Product Category | Contribution in sales turnover (%) 1994 |

Contribution in sales turnover (%) 2000 |

|---|---|---|

| Chocolate | 59 |

64 |

| Sugar confectionery | 9 |

12 |

| Food drink | 32 |

24 |

Cadbury’s main manufacturing facilities are at Thane (Maharashtra), Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh), Hydrabad (Andhra Pradesh) and Pune (Maharashtra). Cadbury also outsources manufacturing to third parties (vendors) located at Phalton, Warna and Nashik in Maharashtra. The raw material is procured from Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Table 23.7.2 Cadbury: Income and Profit Growth

| Year | Income (INR million) |

Profit after tax (INR million) |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 6263.2 |

597.2 |

| 2000 | 5711.4 |

523.1 |

| 1999 | 5110.8 |

412.3 |

| 1998 | 4283.3 |

264.2 |

| 1997 | 3541.4 |

185.7 |

| 1996 | 3118.0 |

203.2 |

Source: Annual Reports

The company controls its marketing operations through four regional offices located at Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai. Under each branch there are four to six depots managed by carrying and forwarding agents (CFAs). There are 27 CFAs located across the country. The material is supplied to CFAs from four warehouse hubs located at Thane, Gwalior, Hydrabad and Pune. These CFAs supply the material to 2100 stockists, which in turn serve 4,50,000 retailers. The company has a total consumer base of 60 million.

Fig. 23.7.2 Marketing supply chain at Cadbury’s

As the product melts above 35°C, the Cadbury warehouses are installed with temperature-controlled facilities. The CFAs store the products in cold storages with the storage area varying from 2000 to 5000 sq ft. The hub warehouses are bigger with the area varying from 20,000 to 45,000 sq ft, depending on the demand in the region. The product is transported through refrigerated vehicles. The average pack size is 2′ × 2′ × 2′ with a maximum weight of 20 kg. Cadbury has excellent connectivity with branches, CFAs and stockists. The company has a well-developed and extended IT support for the distribution network. Cadbury is attempting to improve the distribution quality. To address the issue of product stability, they have installed Visi coolers at several retail outlets.

For product transportation, Cadbury uses two types of vehicles—the insulated (for chocolates) and the non-insulated (for other products that are not temperature sensitive). In 85 per cent of the cases they go in for containerized vehicles, while in the remaining 15 per cent they use open trucks. All consignments are full-load trucks.

Currently, the company is outsourcing transportation to various parties. In the insulated vehicle category are included NFT, Fresh Express, Assam Transport, Haryana FC, Interstate and others, while the dry-type vehicle category includes Best, DRS, Shivalaya, East India Transports and TCI. The logistics cost on the distribution side is around 10.5 per cent of the sales value. The contribution of transportation cost and warehousing cost in the logistics cost is to the extent of 45 and 55 per cent, respectively.

Cadbury is presently maintaining 15 days finished goods inventory at its various warehouses and 18/20 days at the CFA’s place. For cost reduction the management is planning to reduce the inventory level further down to 8/10 days at warehouse hubs and 15/16 days at CFA’s place, without losing on the market front. The major deciding factor is the demand accuracy. Although the firm has excellent connectivity with the warehouses and CFAs, it has no direct interaction with the retailers and the customers.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What measure/s should the company adopt for reduction of inventory level, without compromising on customer service and market share?

- Does Cadbury need to undertake any major changes in its distribution network?

- Discuss the nature of logistics programmes the firm needs to evolve for different channel members?

- “Demand management is essential for operating a lean supply chain.” Discuss. How should Cadbury tackle the issue of demand management for chocolates?

Case 23.8

MWC LTD.*

Looking Beyond the Role of Warehousing

Warehousing Industry

Warehouses in India are divided into two broad categories: (1) warehouses for agricultural produce and (2) warehouses for manufactured products. The warehouses for food grain storage are well organized, as these are mostly under government control. There are two major public warehousing organizations, e.g. Central Warehousing Corporation and the State Warehousing Corporations. They cater to a part of the government’s food grain procurement requirement in handling and public distribution system. In addition to these, Food Corporation of India (government controlled) has a network of its own warehouses, exclusively devoted to the public distribution system. The other agencies are run by the cooperative sector at the village and the taluka levels for storage of food grains. However, the total storage capacity of these agencies (39 million tonnes) is inadequate to take care of the food grain production in the country, which is at the level of 210 million per annum.

For manufactured products the traders and manufacturers use either private, pubic or contract warehouses, or a combination of these, for storage of goods for distribution. This industry is highly fragmented. The privately owned public warehouses offer a variety of services to the depositors and there is stiff competition among the service providers. However, these warehouses do not operate on economies of scale and use manual material-handling methods. As a result, the profit level in these warehouses is low. After liberalization, due to market needs, many foreign-based logistics service suppliers have entered the market and are offering integrated logistics service solutions to their clients. They are building mega-capacity warehouses to operate on scale economies and using the latest technologies to enhance productivity and speed in delivering the products to clients.

MWC Profile

MWC Ltd. was established in 1950 in the state of Maharashtra with two warehousing centres. It is one of the oldest warehousing corporations in India. Over a period, MWC has grown into 130 warehousing centres with a total storage capacity of 10 million tonnes in 2001.

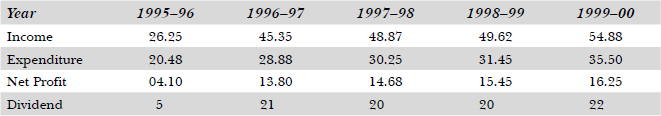

In the beginning MWC was storing stocks from primary agricultural producers and local traders. However, slowly MWC has expanded its activities and started storing all types of agro-based products and fertilizers produced in the country. It started with accepting cement and fertilizer from private and public sector undertakings for storage. MWC is now catering to the needs of importers and exporters through bonded warehouse and container freight stations. It also started storing cotton bales from cotton growers. Ever since its inception MWC is continuously making profits. The financial performance of the company during past five years was excellent and they offered not less than 20 per cent dividend to their shareholders during the period.

Table 23.8.1 Financial Performance (INR Crores)

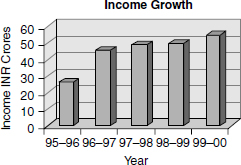

MWC warehousing space growth is one of the fastest in the industry. It is adding more than 50,0 tonnes of storage capacity every year since the last 4–5 years. The compound growth observed was 10 per cent per annum.

Fig. 23.8.1 Income growth

Fig. 23.8.2 Warehouse capacity growth

The firm’s storage capacity is mostly used for the storage of food grains and other agro-based products. The depositors are mainly cooperatives, public sector undertakings (PSUs), fertilizer firms, traders, and so on.

Fig. 23.8.3 Productwise utilisation

Fig. 23.8.4 Depositorwise utilisation

With the changing face of trade and commerce due to liberalization of the Indian economy, MWC is facing severe competition from the logistics service providers who are developing their network of warehouses and providing integrated logistics services. Further, the MWC’s warehouses are mostly constructed for storage and handling of food grains and agro products.

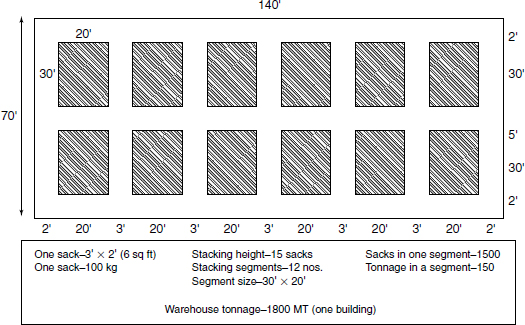

Business Portfolio

Warehousing Centres. The firm has 130 warehousing centres with 10 million tonnes storage capacity in the state of Maharashtra. These centres are located at the major district and taluka levels and at the major food grains and cotton seed producing and trading centres in the state. The products stored are food grains, cereals, pulses, spices, oil cake, coffee seeds, newsprint reels, cement, fertilizers, sugar, jaggery and industrial products. The storage of industrial products is done at the major industrial centres such as Pune, Nashik, Mumbai, Aurangabad, Jalgaon and Nagpur. The industrial manufactured products contribute 18 per cent of the throughput in tonnage per year. The average storage capacity of one warehouse centre varies from 1800 to 18,000 tonnes of food grains. At one warehouse centre there may be 3–10 buildings, each of such building is 140′ Lx 70′ Wx 30 Ht and can store 1800 tonnes of food grains. The inside storage arrangement is similar to the one indicated below. The maximum permissible storage height of the food grain stack is 15 layers of sacks, each of 3′ × 2′ size, which contains 100 kg of food grains. The storage space in the building is divided into 12 segments, each 30′ × 20′ size and with sufficient space in between the segments for ventilation and movement of persons.

Fig. 23.8.5 Storage arrangement for foodgrains

A good percentage of the warehouses (50 per cent) is more than 20–25 years old and was built to support the public distribution system of the government. The storage capacities of MWC are divided into six regions:

All the warehouses were designed and built for the purpose of storage and handling of agro-based products. Some 3–6 persons, depending on the capacity of the warehouse and the level of throughput, manage each of these warehouses. The stock turnover ratio of these warehouses for food grain is around 8–12, depending on the location. After liberalization of the Indian economy in 1991, MWC began storing products from the manufacturing sector as well. The company finds storing these is remunerative and hassle free, especially from the point of view of less decay and damages during storage, which is otherwise a normal feature for food grains storage. This activity was undertaken by the company at a few places like Mumbai, Pune, Aurangabad, and Nagpur. The stock turnover ratio in the case of industrial products they discovered was 15–18. The warehousing charges for food grains were Rs 4–5 per sq ft per month (food grain being an essential commodity, there was government involvement in distribution and rate fixation in consultation with FCI), while for industrial product they were charging a 30–40 per cent higher rate, according to the warehousing industry practices. Currently, the FMCG companies are shifting their focus from urban to rural markets. They are on the lookout for a warehousing chain to stock their product at strategic locations across the state of Maharashtra so as to penetrate the rural market. This is an excellent opportunity for MWC to deploy its warehousing chain for storage and distribution of products form the manufacturing sector and earn more profits.

Table 23.8.2 Regionwise Storage Capacity of MWC

| Region | Number of Warehouses | Capacities (000 tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| Pune | 20 |

1650 |

| Mumbai | 8 |

750 |

| Sholapur | 14 |

950 |

| Aurangabad | 12 |

1100 |

| Jalgaon | 22 |

1600 |

| Parbhani | 20 |

1550 |

| Nagpur | 21 |

1430 |

| Nashik | 13 |

970 |

| Total | 130 |

10,000 |

Customs Bonded Warehouse. MWC is operating customs bonded warehouses for import-exports cargo. These warehouses are located in a few places like Mumbai, Pune, Aurangabad, Nahsik, Thane, Navi Mumbai, Jalgaon, Ratnagiri and Nagpur. The business is remunerative because in most of the cases manufactured industrial products are warehoused and the charges are to the depositor’s account. The storage rates here are similar to those for industrial products. However, this accounts for 6–8 per cent of the total business of the company.

Container Freight Stations. To cater to the needs of exporters, the firm has started four container freight stations at Pune, Nagpur, Mumbai and Jalgaon. This is a highly remunerative business and requires a great deal of coordination among the exporters, container-leasing firms and customs authority. Container freight stations (CFSs) are totally devoted to the exports business. However, the firm has plans to expand in this area of business for domestic cargo movements.

Cold Storages. This is a new area wherein the firm has recently entered. MWC has set up a 1000 MT cold storage facility at Navi Mumbai for storage of perishable agricultural products such as fruits and vegetables. The construction cost of the cold storage is around Rs 3000 per MT as against Rs 300–400 per MT storage capacity for dry cargo. Due to the ever-increasing electric power tariff rates, the operating cost is very high. The facility needs to be run on economies of scale for cost advantage. The major cost-spinner in this business is electric power. MWC is planning to use an emerging technology like the ammonia absorption system wherein the energy requirement is 15–18 per cent less than the conventional system run on electricity. There is an excellent scope for cold storage business, as the cold storage capacity is merely sufficient to store 9–10 per cent of the total fruit and vegetable production (110 million tonnes) in the country. According to the surveys conducted by the government and other private agencies, 33 per cent of fruits and vegetables produced in the country perish before these are consumed or processed, mainly because of inadequate cold storage infrastructure in the country. Another area for cold storage requirement is floriculture products, which have great export potential. Currently, cold storage facilities are in great demand in the floriculture, pharmaceutical, horticulture and food processing industries.

Organization Set-up. The firm is headed by the managing director, who is assisted by the general managers heading operations, finance, engineering, administration and business development. The business development department looks after site selection for new warehouses, feasibility study and market development activities. The engineering department is responsible for construction of new warehouses; maintenance of the old ones; and maintenance of the food grain stocks through usage of pesticides and fumigation process. The operations department is concerned with the marketing of storage space, market development and maximizing the storage capacity utilization of the firm. The present average capacity (floor area) utilization over the year is 75 per cent.

In order to avail of the emerging marketing opportunities in a highly competitive environment, The MWC management has done a SWOT analysis to take stock of the situation for formulating a strategic plan for future growth.

Strength

- Excellent warehousing network and geographical coverage

- Huge storage capacity

- Known for food grain storage

- Established customer base

Weakness

- Capacity utilization on the lower side

- Low stock turnover ratio

- Small capacity warehouses

- Manual material-handling facilities

- Traditional way of connectivity in the network

- Low productivity

Opportunities

- Increased trading and distribution activities for manufactured products in FMCG, pharmaceutical, retail chain, automobile and lifestyle products industries, because of liberalization of the economy and emergence of WTO directives

- Other areas of logistics such as transportation, packaging, inventory management in great demand in the manufacturing and trading industry

Threat

- Proliferation of a new breed of logistics companies (mostly with foreign associations) offering integrated logistics solutions

- New logistics companies offering value-added service

- Logistics companies creating mega storage capacities with technology backup to have economies of scale

REVIEW QUESTIONS

For remaining competitive the MWC has to answer the following questions:

- How to increase the productivity of the system?

- Should the company continue to store food grains (where business is assured) or make a shift to storage of manufactured products (facing competition)?

- Whether to continue as warehousing service provider or change the role to an integrated logistic service provider?

- What other logistics products can be offered to the customer as value addition?

- Does MWC need a restructuring of the organization?

Case 23.9

ROX DOC-CARE*

Meeting Market Requirements of Document Warehousing

NEW CONCEPT

ROX Doc-Care (RDC) offers a complete documentation management solution for any organization in India. This Indian venture was started by a group of young professionals for providing the services of warehousing for storage, handling and retrieval of the physical documents over a period, as specified by the depositing company. In today’s cost-conscious and competitive environment, the organization needs to have a complete control over the information documented in the physical or digital form. Organizations are under strategic and legal pressure to keep the documents accessible (to the concerned parties) for information contained therein anytime. These services are, traditionally, organized by the business firms internally. However, many firms pose problems in the maintenance of documentation over a longer period of time due to inadequate resources, or because of an unwillingness on the part of the management to allocate the funds to create such a facility, which is not regarded as a core area of their business operations. The solution to this problem is to outsource this service to someone who is expert in the area and does it for you efficiently and effectively at the least cost. Looking at the growing need of the corporate clients and potential market for such services, RDC started this venture in Mumbai in 1995. This is the first time such services were made available in India to the corporate clients.

RDC provides an efficient IT-enabled storage and physical retrieval system for all major physical documentation media including papers, computer disks, tapes, (master audio and video tapes), films, optical disks, X-ray films, blueprints and product samples. The company’s services include pickup and delivery, filing and organizing, retrieval and destruction of records, database management, and management reporting. The key business drivers of RDC are:

- Providing rapid access to data and reaching the physical data at the right time and place

- Reliability, consistency and confidentiality in services

BUSINESS PROCESS OUTSOURCING

Business process outsourcing (BPO) is gaining momentum in Indian markets. Outsourcing has become an accepted trend after the liberalization of the Indian economy in 1991. In the Indian market the BPO vendors, especially in the CRM and transaction processing segments, are developing rapidly. So far companies in the BPO segment have focused on business development and building delivery capabilities and have grown organically. In the medium-to-long term, tier I companies seek to scale up rapidly, and the rest will expect consolidation to occur either by acquiring tire II/III companies or through mergers among them. Currently, Indian companies offer specialized services or multi-process solutions, such as treasure management, fund administration, customer support, telemarketing, logistics and HR functions. These companies will further build up expertise in multiprocessing in an effort to add value to their offerings. BPO vendors are currently bagging basic people-intensive projects, as the whole movement towards BPO is relatively new and expected to gain momentum in future. The future trends will not be simply to outsource a single function, but to outsource a whole process. This is similar to what clients today prefer: buying a complete system on turnkey basis rather than procuring the individual system components, parts or product and integrating or assembling it themselves. The companies will outsource the entire HR department as opposed to outsourcing only the payroll function.

In the current scenario, organizations store their physical documents either in their office areas or at off-site locations. Some of these documents are required to be stored for statutory purpose, but most are accessed once or twice a year. This leads to inefficient and expensive use of space, which carries a price premium in most central locations in the metros. Hence, systematic record keeping and corporate archiving are important for future referrals.

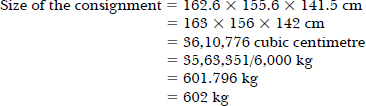

RDC SERVICE OFFERINGS