CHAPTER 3

Major Luxury Sectors

We are so used to the idea of luxury brands that we tend to forget that this is a relatively new concept. For many years, businesses that we now include in the luxury sector were considered completely separate and were represented by different federations: the Federation of Ready to Wear, the Federation of Leather Goods, the Federation of Perfumes and Cosmetics, and so on. On the face of it, in the manufacturing and sales processes, a bottle of champagne and a lady’s dress have very little in common. The champagne is produced through an automated system using very modern machinery. It is then sold in wine stores, but also in supermarkets and hypermarkets. However, a lady’s dress is often made by hand and in very limited numbers, and sold in exclusive luxury stores around the world.

The French were probably the first to understand the fact that a bottle of champagne and a sophisticated dress do have something in common, and this is why in 1954 they created the Comité Colbert, an association to promote the concept of luxury.

The stated values of Comité Colbert could be an introduction to the global luxury concept—its members, it informs us, “share the same ideas of a contemporary art de vivre, and constantly develop and enrich this through their diversity. They have a common vision of the importance of international ambition, of authentic know-how and high standards, of design and creativity, and of professional ethics.” Its members are drawn from the following metiers, or trade activities:

- Haute couture and accessories

- Perfumes

- Jewelry

- Designer homeware

- Hotel and gastronomy

- Great wines, champagne, and cognac

- Publishing

- Decorative arts

When the Comité Colbert was created and the concept of luxury business developed, it wasn’t immediately obvious that these metiers had so much in common. Now, however, the idea is commonplace, as this book can testify.

It is interesting to note that the Comité Colbert does not include luxury automobiles, probably for the simple reason that France does not manufacture any. While hotels are included, there is no mention of luxury cruises, special airline activities, or specific or cultural travel agencies.

In this chapter, we will describe the luxury world by individual sectors, so that their characteristics and key success factors can be clearly identified.

Ready-to-Wear Activities

In this section we include both ladies’ and men’s ready-to-wear and haute couture, which in Chapter 2 we estimated to amount to €22 billion in volume.

While other businesses such as perfumes and cosmetics or wines and spirits may have greater sales, in image terms, the luxury fashion business is undoubtedly the most important. Through its fashion shows, its constant renewal, and its leadership in new trends, new shapes, and new colors, it remains the sector that is most frequently mentioned in the press and that is most closely associated with the artistic world.

While the majority of students in luxury programs want to end up in the fashion business, less than 20 percent of the luxury jobs are in a field in which most staff is in stores, presenting and selling the merchandise to the final consumer. As we saw earlier, marketing teams are quite small and production is generally subcontracted. Unfortunately, this is also a field in which profitability is not always easy to achieve. For many brands, the fashion business remains unprofitable; we will try to explain why.

In this section, we will describe the specific fashion markets, the key management issues, and the most common organizational structure found in this sector.

The Fashion Business and Its Operation

The Players

The Italian business is by far the strongest, with worldwide sales that we estimate at around €13 billion (without accessories).

The Italians arrived on the luxury fashion scene later than the French, with Armani, Gucci, Prada, Valentino, and Versace, for example, coming to the fore in the mid-1970s and 1980s. In some ways, they are better positioned than the French in that they are still perceived as new, and they provide great creativity, opening new stores in the major cities of the world. Customers love the appearance of newness that the Italians have been able to build into their brands. While twenty years ago, in the top luxury shopping complexes, such as the Imperial Tower in Tokyo or the Peninsula Hotel in Hong Kong, most stores were presenting French fashion brands, today Italian brands are much more present and more powerful. Customers are attracted by their sophistication and the quality of their products.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that many of the top Italian brands did not start out in the fashion business. Guccio Gucci, for example, was a handbag manufacturer; Salvatore Ferragamo was a shoemaker; Edoardo and Adele Fendi were fur specialists; and Mario Prada designed and sold handbags, shoes, trunks, and suitcases. But, from their craftsmanship base, they were able to start ladies’ ready-to-wear lines that were interesting, creative, and fashionable.

Take Fendi. As a fur brand, Fendi was less known and less powerful than Revillon. However, while Revillon stayed as a pure player, selling fur almost exclusively in a declining market, Fendi began to distribute shoes, then leather ready-to-wear, then very successful ladies’ handbags. In the 1970s, it hired Karl Lagerfeld to design a ladies’ ready-to-wear collection. At first it sold very little, but it persisted and now, with sales around €400 million, Fendi is a fully fledged brand, strong in both handbags and ready-to-wear. For its part, Revillon began to move away from fur, but not until the 1990s. Its approach lacked strength, intelligence, and consistency, and today the brand has almost disappeared.

As they moved away from their original businesses and into ready-to-wear, the Italian brands found a very receptive local community with strong fabric creators, with many ready-to-wear manufacturers and subcontractors and a creative, open environment that was ready to take risks. For many years, the Fendi ready-to-wear was produced through an outside licensing agreement and sales were very small. While it was not always profitable, it received strong and intelligent support from the company and, over time, this support has paid off.

Italy has never promoted haute couture, even if brands like Armani or Valentino are happy to be part of the Paris fashion shows. They believe in creative ready-to-wear lines that sell in the stores, and put all their efforts into lavish twice-yearly fashion collections. And the products sell.

Though the Italians have fewer licensing deals than the French, they still have many selective licenses, as we will explain later. The market is open, without any one brand claiming an exclusive position. The industrial sector is also open, and fast. Though Prada has been producing ready-to-wear collections for fewer than twenty years now, it is perceived as a very strong fashion brand, as if it had always been that way.

From the start, the Italian brands were run with a mix of creative talent and strong business competence. Franco Moschino developed his own business with a very strong manager, Tiziano Gusti; Gianni Versace first developed his brand with a strong businessman who was one of his classmates, Claudio Luti; and Giorgio Armani started his business in 1975 with the late Sergio Galeotti and has become a very rare breed—a designer who is also a businessman.

The French business is more traditional, with the strongest brands, such as Chanel and Dior, having been created before, or immediately after, the Second World War. The French were innovators at that time, with Christian Dior inventing the licensing business that later became the raison d’être of many brands, including Pierre Cardin. In addition to creating haute couture, they were the first to develop perfume businesses, using their names and images—first, Coco Chanel in 1921, then Carven and Dior immediately after the war. To this day, French fashion brands have a strong presence in the perfume business.

However, the French, in a traditional Gallic way, also invented barriers to entry. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was quite difficult to create a new fashion brand in France. Launching an haute couture collection was expensive and difficult. French ready-to-wear manufacturers were very few and did not want to handle small or upcoming brands. New brands were thus obliged to subcontract their ready-to-wear lines in Italy.

The newcomers then began to position themselves as creators, making dresses that would command immediate notice; but this did not work well, either. In the last twenty-five years, only Kenzo and Jean Paul Gaultier have been able to create fully fledged brands. Thierry Mugler has developed awareness and a thriving perfume business, but not a strong, viable fashion business. Claude Montana was certainly one of the most gifted creators of his generation, but his business is no longer strong. Other gifted creators, such as Angelo Tarlazzi, Myrène de Prémonville, Azzedine Alaïa, and Hervé Léger, have a reason for being but have been unable to establish lasting fashion brands.

A new generation of designers with a strong business sense, such as Regina Rubens or Paul Ka, is now emerging. In the long run, they may well create strong worldwide brands.

Table 3.1 highlights the brands that have achieved sales of over €500 million. They have managed to do this because they can invest heavily in advertising, have the necessary volume to open stores almost anywhere in the world, and have the customer attractiveness necessary to break even. These are the brands that can generally be found in the major luxury shopping galleries of the world.

TABLE 3.1 Fashion Mega-Brands (Sales above €500 million)

| France | Italy | |

| Chanel | Armani | Max Mara |

| Dior | Dolce & Gabbana | Prada |

| Hermès | Ermenigildo Zegna | Salvatore Ferragamo |

| Louis Vuitton | Gucci | |

Table 3.2 illustrates what we might call the second-tier companies: those that have achieved sales in excess of €100 million. (Below this level, brands can be national or strong in two or three countries, but cannot have a direct presence in the major markets of the world.) With this size, it is possible to have profitable stores, perhaps not in every major city of the world, but certainly in those such as New York and Hong Kong, where there are enough luxury specialists to make it profitable.

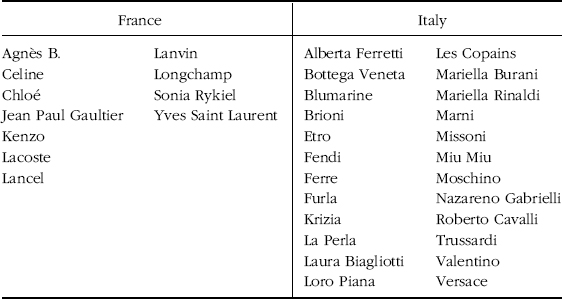

TABLE 3.2 Second-Tier Fashion Brands (Sales of €100–€500 million)

Unfortunately, companies with sales below €100 million cannot easily afford to open stores around the world and, even if they could, they probably don’t have the awareness, the potential, or the merchandise attractiveness to make those stores profitable.

We had originally intended to include only fashion brands, but then only Chanel and Dior would have been included on the French side of Table 3.1. This would have been unfair to Louis Vuitton and Hermès, which are among the most powerful French brands and which are also engaged in ready-to-wear activities. For this same reason, we were forced to add Lancel, Longchamp, Furla, and Bottega Veneta to Table 3.2.

In doing so, we clearly show the strong advantage in size, diversity, and power the Italian brands have over their French counterparts. We ought not to forget that in leather goods the French have a very strong advantage, with their two major brands being above everybody else in this product category.

Other nationalities are also part of this business, but they cannot be compared with either the French or the Italians. The Americans—Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Donna Karan—have done quite well in developing a new concept of lifestyle brands, that is, products geared to a specific style. The creator in each case is also a businessperson and has developed ready-to-wear products addressed to a specific type of clientele. Ralph Lauren does this beautifully with his Old England and New England traditional style, which fits a certain wealthy clientele looking for nostalgic products conveying a country atmosphere to clothing that will be worn in an urban environment.

But to be effective, the American lifestyle concept requires heavy advertising budgets, which has created a barrier to entry that makes it difficult for newcomers to be part of this very sophisticated crowd.

Perhaps because of its climate, Britain is home to two very important businesses that were first built around raincoats: Burberry and Aquascutum. Britain also has successful, strong men’s-wear brands such as Paul Smith, Dunhill, and Daks, not to mention Jaeger, a knitwear brand positioned at a middle range. Newcomers like Vivienne Westwood bring something interesting, but are still small by world standards.

Germany has Escada and Hugo Boss, which used to belong to the Italian group Marzotto. Two of its brands are particularly interesting, because they are different: Jil Sander, because she first developed a strong collection for executive women, and Joop, because he developed a very strong name in German-speaking countries on the basis of licensing deals.

Spain is home to the internationally renowned brands Loewe, Purificación Garcia, and Adolfo Dominguez. Other creators, like Pertegaz, Victorio y Luchino, Roberto Verino, and Toni Miro, are strong at home but have never been able to develop beyond their own country.

Belgian designers Ann Demeulemeester and Dries Van Noten should be included on the list, as should Switzerland’s Akris.

The reason for speaking of nationalities and looking at overall business volume is because luxury fashion is a business and should be considered as such. The objective of a ready-to-wear luxury brand is to become a worldwide success. As we will discuss later, the nationality of the designers has a strong impact on the positioning of the business outside their respective national territories.

How to Develop a Brand

As a brand starts locally and develops, it needs to do things correctly from the outset. This process requires both a strong creator and a strong businessperson. The creator has to develop a unique style, but should also have someone close by who can be relied upon to take care of business development, and channel that creativity into areas that translate into sales without constraining the designer’s creativity. The partnerships of Giorgio Armani and Sergio Galeotti and of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé are object lessons in the kind of teamwork that is required for success. A strong and trusting relationship, with complementary styles and instincts, is very important to the development of a ready-to-wear brand.

The ladies’ ready-to-wear line is what gives a strong identity to many successful brands. It provides press coverage worldwide and creates awareness in retailers and consumers alike. As brands develop the total-look concept, ready-to-wear acts as the anchor; it is very difficult to sell branded belts, panties, or shoes without a strong image for dresses or ladies’ suits.

To develop a brand, it is necessary to have a presence in many large cities around the world, and ladies’ ready-to-wear is the way to go, as it enables the creation of a network of retail stores under the brand name. These stores often sell more accessories and handbags than ready-to-wear, but it is the ready-to-wear line that makes the shop window attractive and creates a fashionable store environment. It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg proposition: To sell accessories and handbags requires a strong name and a strong ready-to-wear line. To be able to develop and promote a strong ready-to-wear line requires the volume obtained through the sales of handbags and accessories.

How to Make Money

The paradox is that many ladies’ fashion activities are unprofitable. As we will see later, the setup of a new ladies’ ready-to-wear collection requires expensive prototypes, runway products, and showroom collections that are profitable only when the volume is there. This is also the case for men’s ready-to-wear lines, which are often difficult to differentiate from one another. Store activities are also very dependent on their level of sales. In other words, it is not possible to make money opening a store for a brand that is not well known and not fashionable and attractive enough.

In fact, as we will discuss later, the best way to finance the startup and development of a ladies’ ready-to-wear collection is to develop license deals in other product categories.

What must be said here is that many brands are losing money in this area. Eurostaff undertook a study of the profitability of twenty-one French ready-to-wear brands in 1994. Of these, only seven showed significant profits, three just broke even, and eleven lost money. And Chanel, with a net profit equivalent to €67 million on ready-to-wear sales of €570 million, was more profitable than the rest of the sector combined.

Key Management Issues

The Creative Process

We return here to the most important element of style: the creator.

The role of management within this area is to organize a workable plan that sets out the requirements for the coming season: How many suits with pants? How many suits with skirts? How many cocktail dresses? It will also specify retail price targets and the target cost of the fabric to be used. The designer must then perform and create within these precise guidelines to ensure that the final product will sell at an acceptable price in the stores.

Similar planning is also required for accessories and other products, each of which must be coherent with the rest and readily identifiable with the brand. A Dior tie should be distinguishable from an Yves Saint Laurent tie, and each product bearing a brand name should bring a specific quality and an added value to the total product group. This can be realized only through coordination and clear design directives.

While management should not be directly involved with the creative process, it must set the rules and the processes for planning and reviewing, for harmonizing the different product lines, and for analyzing what has or has not been selling. Management should also take charge of ensuring the quality of raw materials (fabrics, buttons, technical materials, lining, and so on) and of manufacturing.

The creativity of people such as Karl Lagerfeld and Giorgio Armani should not be controlled. It is simply a matter of setting guidelines, objectives, and reviews, so that the creative process can be used to improve the brand’s standing in the marketplace.

A Worldwide Presence

The balance of activity for a fashion brand takes into account image-creation items, such as freestanding flagship stores in major cities, and image-consumption activities, such as licensing deals for secondary products.

The distribution of ready-to-wear fashion products varies in accordance with the particular needs of specific markets. In the United States and Japan, for example, luxury fashion brands are distributed mainly through department stores. The buyers of the different stores visit the Milan and Paris fashion shows and buy by brand in accordance with their open-to-buy budgets. This is the most important engine of brand development. However, if the brand wants to create a special strength or awareness on its own, it must also build its own flagship stores in New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Osaka, and other influential cities.

In other countries, European brands use an importer or a distributor to take charge of developing sales in a given territory. This requires a showroom and a showroom collection whose products end up in multibrand stores and local department stores that do not buy direct.

In countries such as Hong Kong or Singapore, the business is run in part by individual fashion retailers, such as Joyce in Hong Kong or Glamourette in Singapore. These retailers are strong at identifying new brands with potential and buy them before anyone else in the country.

Why Is It Difficult to Make Money?

In ready-to-wear, it all boils down to the volume of business created and sold. In fact, when the volume is not there, the cost of manufacturing a dress becomes extremely high.

If we take a women’s suit sold at retail for €950, the wholesale price will be about €395 (that is, a markup coefficient of 2.4). Table 3.3 gives an indication of how manufacturing costs vary with volume.

TABLE 3.3 Cost of Making a Women’s Suit in France (€)

| If Large Volume | If Small Volume | |

| Manufacturing cost | 100 | 300 |

| Accessories (buttons, lining, etc.) | 50 | 60 |

| Fabric | 100 | 115 |

| Total Cost | 250 | 475 |

The manufacturing cost can be multiplied by two or three if the item is to be made in small volumes. In such cases, it becomes too expensive to use a laser cutter, and the way in which individual pieces are located on the fabric may not be as economical as with larger volumes. The process of making the suit may then become entirely manual, with no guarantee that the quality is much better at the end of it.

The economic picture is also dependent on whether the products are all sold at full price, or if some have to be sold at bargain prices, with discounts that can range from 30 to 70 percent. When production runs are small and most products are sold only at bargain prices, profitability is certainly no longer on the horizon, keeping in mind that in a good season only 50 percent of the collection of a relatively unknown brand is normally sold at full price.

This is where license deals come into the picture, as they provide the cash necessary in the early days to invest heavily in ready-to-wear and to ensure it is successful.

The Most Common Organizational Structure

Within many luxury fashion brands, the position of marketing manager does not exist. The reason for this is that the role of the marketing manager is to find out from the consumer what the brand should be, which could be in direct conflict with the designer, whose job is to create what the consumer should have. Nevertheless, it is extremely necessary to have one person whose rare competence is to be able to provide unobtrusive guidelines that force the designer to look at what happens in stores. This position is generally referred to in U.S. and UK fashion circles as the merchandiser.

Another role within luxury fashion is that of the communications and/or public relations manager. This person generally reports to the general manager and acts as a conduit between the GM and the designer.

Luxury fashion structures seldom have factories (there is generally a purchasing manager or a supply-chain manager in charge of products). So the most important jobs fall within the field of store activities: store managers, of course, but also area managers, country retail managers, regional retail managers, and worldwide retail merchandising manager.

As we have mentioned, the number of staff is limited and is in direct contact either with the designer or with the final consumer.

Perfumes and Cosmetics

As we saw in Chapter 2, this is one of the largest luxury sectors, with total sales estimated at around €37 billion. It is also the largest in staff, as it employs probably more than 30 percent of all luxury-goods employees. It is also relatively concentrated, with Paris, New York, and Geneva being major headquarters.

This business entails selling standardized products in large quantities at low unit prices and, in this, is somewhat reminiscent of the fast-moving consumer-goods market. However, as we will discuss, this is a very different market, because the consumer expects to find a product with a very high aesthetic content that is special every time.

The Market

This is, strangely enough, a relatively recent market. For many years individual perfumers would extract fragrances from flowers through an alembic, as described in Patrick Süskind’s novel, and subsequent film, Perfume. Perfumers generally had another activity; they also sold gloves. This is why a French perfumer is now developing retail stores under the name “Parfumeur et Gantier” (Perfumer and Glovemaker). The mass-market business of selling the same standard product over time to a larger population started in the eighteenth century in the city of Köln, where they developed the Kölnish Wasser or Eau de Cologne under the German brand 4711. Guerlain came into being at the end of the nineteenth century. All other brands were started in the twentieth century: Caron, then Chanel, Patou, Lancôme, and Lanvin. Most of the major brands, such as Estée Lauder, Dior, Armani, and Ralph Lauren, were created after 1950.

Given the fact that the average product is sold at retail for less than €50 and that the total sales of €37 billion includes products sold at wholesale and export prices, it is likely that as many as two billion units of luxury products are manufactured and bought every year. In major developed markets, product penetration reaches 80 percent of households, with a minimum purchase of one to two units a year for perfumes and much more for cosmetics. This is a very large market.

Consumer Expectations

When buying a perfume, consumers look for an intensely personal, sensuous, almost narcissistic, pleasure, which comes from holding and opening an aesthetically pleasing bottle and breathing in a sophisticated scent that conveys a sense of luxury and personal satisfaction. They are also looking for social reassurance; they want to appear sophisticated and to have good taste. Perfumes provide a personal dream of luxury at a reasonable price. It is great to be able to afford the luxury and sophistication of Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent for less than €50.

For cosmetic products, customer expectations are quite different. For makeup, which women often carry in their handbags, products have strong social connotations; there is a much greater degree of sophistication conveyed by opening a handbag and taking out a Chanel lipstick than there is in pulling out a mass-market product from the same handbag. For skin-care products, expectations are again different, as they deal with a long-term investment in personal appearance—the need to look good and the hope of remaining good looking for a long time.

What is clear is that consumers are looking for much more than is actually contained in the bottle. This is why knockoffs (those cheap perfumes sold for a couple of dollars in U.S. supermarkets, claiming, “If you like Youth Dew from Estée Lauder, you will love perfume number 17”) have never done well. Of course, the fragrance is an important part of the deal, but the perceived quality of the bottle, its aesthetic value, and the social reinforcement it provides is certainly much more important.

In fact, consumers are much more interested in what we might call the environment of the product than in the product itself.

Product Types

For perfumes, the mass-market segment has never really worked. Only 20 percent of perfume units are sold through mass markets; this has not changed in the last twenty-five years. Major mass-market merchandisers have offered extended low-price ranges without significant success. Most women, whatever their level of income, prefer to buy a €50 Dior perfume in a sophisticated perfumery or department store than spend €10 on a little-known brand in their supermarket.

The makeup category is divided into two subsegments. For social makeup (lipstick or touchup products that women carry in their handbags and use in front of others), women buy—and will continue to buy—the right brand and in a sophisticated environment. On the other hand, for personal makeup products (such as nail polish), most of the buying is done in supermarkets or other mass-markets distributors, which represent around 75 percent of unit volume.

Skin-care products are a different case again. In the 1950s and 1960s, most products were sold through department stores and perfumeries, as consumers were looking for advice on which products were suited to their specific skin type. Today, consumers are much more knowledgeable about skin-care products. Most of the units purchased (around 80 percent) are bought through mass-market distributors. Mass-market brands such as Plénitude de L’Oréal or Procter & Gamble’s Oil of Olay have done a very good job in catering to such a market.

Of course, the €37 billion we mentioned relates only to the luxury part of this market. How this will evolve over time remains to be seen, but it will all depend on the quality of the products and the diversity of the luxury segment. What we can say is that for a perfume or a cosmetic product, consumers are very interested in the aesthetic values of the bottle or the jar, of the top, of the outer carton box, of the specific luxury positioning of the selective products, and of the dream conveyed by the concept, which all combine to enrich the purchasing experience and the pleasure to be had from using the products.

They are also very interested in the sophistication of the purchasing environment. They want the products to be available but they value the impression of scarcity, as if the products were available only to them. Of course, this is not easy to achieve for products that are sold by several billion units every year.

The concept of so-called affordable luxury for exclusive brands in a sophisticated environment will remain the key to the development of the market for years to come.

The Financial Aspect

The basic principle of luxury perfumes and cosmetics is that the same product, generally manufactured in one single location or, at most, in two or three locations, must be available everywhere in the world with the same luxury presentation to the different national customers.

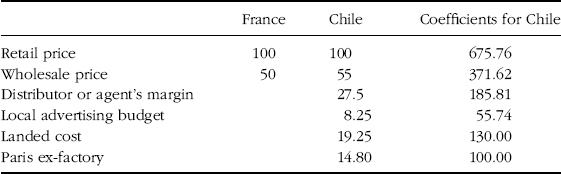

Products must therefore be shipped everywhere and the necessary customs duties must be paid everywhere in the world. The same product must therefore go through different distribution phases depending on the markets in which it is to be offered, as illustrated in Table 3.4.

TABLE 3.4 Comparison of Cost Structures for a Product Sold in Different Countries (Based on an Assumed Retail Price of €100 in the French and the Chilean Markets: Figures Could Equally Be in US$ or Other Currency)

We have taken the example of the same product that would be sold in France and in Chile at the same retail price. In France, things are simple: The company operates with its own sales force and the billing is done at the wholesale level; the company nets €50 for each product that is sold for €100 retail. In Chile, things are a bit more complicated. The product is generally sold by a local distributor who works on a margin of 50 percent of the wholesale value. Also, a special local budget of 15 percent of wholesale (i.e., €8.25) is set aside for local advertising and promotional activities. The landed cost is therefore €19.25, on which duties, freight, and insurance have been paid. This means that the French manufacturer will receive only €14.80 for each €100 of retail sales in Chile. Thus, the system requires very high gross margins in France for the Chilean business to be profitable. In this case, a gross margin of at least 70 percent, and probably 80 percent, is necessary.

While the figures may differ according to the country being targeted, very high margins are generally necessary in the perfumes and cosmetics category. Bear in mind, too, that advertising and promotional budgets (incorporating media advertising, samples, testers, in-store displays, and other PR activities) are very high and can be anything from 15 to 25 percent of wholesale prices.

The Major Operators

The Major Brands

To be strong on a worldwide level, sales of €300 million are necessary. The brands that have achieved this level are listed in Table 3.5.

TABLE 3.5 Brands with Sales Above €300 million

| Armani | Estée Lauder |

| Biotherm | Gucci |

| Calvin Klein | Guerlain |

| Chanel | Hugo Boss |

| Clinique | Lancôme |

| Dior | Sisley |

Of these twelve brands, five (Estée Lauder, Chanel, Dior, Armani, and Lancôme) have sales exceeding €1 billion. All have large advertising budgets (in most cases, above €100 million) and have established a strong presence everywhere in the world.

Also, most of these brands operate in the different segments of the industry. Half—Estée Lauder, Chanel, Clinique, Dior, Guerlain, and Lancôme—operate in all three segments (perfumes, skin-care, and make-up); just two, Gucci and Hugo Boss, deal exclusively in perfumes.

Table 3.6 lists the second-tier brands (those with sales between €100 million and €300 million) also have a strong presence.

TABLE 3.6 Second-Tier Brands (Sales €100–300 million)

| Azzaro | Lacoste |

| Bulgari | Lancaster |

| Burberry | Nina Ricci |

| Cacharel | Paco Rabanne |

| Carolina Herrera | Prada |

| Davidoff | Ralph Lauren |

| Dolce & Gabbana | Salvatore Ferragamo |

| Givenchy | Shu Uemura |

| Issey Miyake | Thierry Mugler |

| Jean Paul Gaultier | Yves Saint Laurent |

| Kenzo |

It is in this group that the fight for survival is the most clear-cut. Of these twenty brands, some are growing very fast while others are in decline.

The group of brands with sales below €100 million offers a different pattern. Those that make up this group are many and varied and include Boucheron, Van Cleef, Hermès, Paloma Picasso, and Salvador Dali.

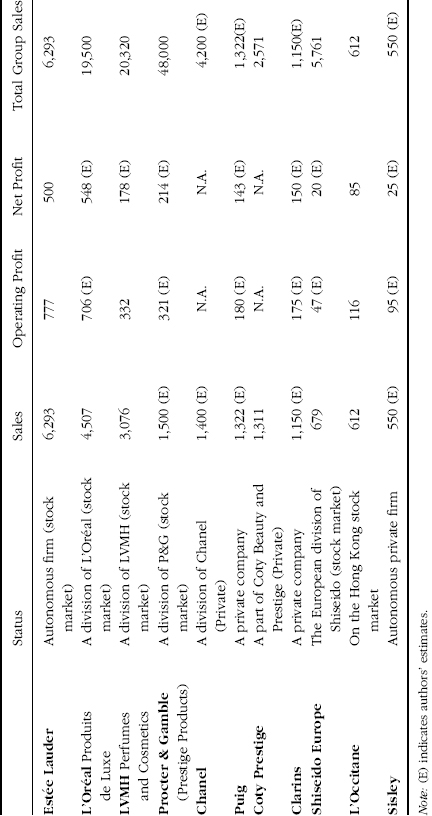

The Major Corporations

This business, despite its creative outlook and its international flavor, is really quite concentrated, with the ten firms shown in Table 3.7 representing about 50 percent of the total sector.

TABLE 3.7 Performance (€ million) of the Major Luxury Perfumes and Cosmetics Companies (2010)

Source: Annual reports or authors’ estimates. For Shiseido, we have taken the figure reported in its annual report. It includes Beauté Prestige International (Issey Miyake, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Narciso Rodriguez) and Decleor (which also includes Carita). It also includes the luxury and mass market distribution of Shiseido in Europe. This figure does not include Prestige luxury products sold in Asia and the Americas under the Shiseido brand.

Estée Lauder, based in New York, began life as a unique cosmetics firm. Today, it is a diversified group that has added Clinique, Aramis, Prescriptives, MAC, Donna Karan (under license from LVMH), and Jo Malone, among others, to its brand offerings. In the past few years, it has developed new modern positioning perhaps best illustrated by what it is doing with Origins. It has come with distinctive brands, sold solely through its own stores, rather than through department stores, using natural or active positioning. The company, still family controlled, is traded on the New York stock market and is very profitable.

L’Oréal, Produits de Luxe, based in Paris, is also a strong operator. It has brands managed from Paris (Lancôme, Armani, and Biotherm, for example), but also operates brands from New York (Ralph Lauren and Kiehl’s) and Tokyo (Shu Uemura). Its Lancôme brand is very strong in cosmetics, but less so in perfume. Its other perfume lines include Paloma Picasso, Guy Laroche, Cacharel, and many others. This division of L’Oréal seems to be very profitable. They purchased from PPR Gucci, in 2008, the perfume brands Yves Saint Laurent (working today as a license) and others like Alexander McQueen.

LVMH perfumes and cosmetics division is the third-largest, thanks to Dior, which represents about half the total. Guerlain is a great brand, but is better known in France than abroad. Though Givenchy has experienced some difficulties in recent years, these appear to have been solved. Kenzo is an interesting growing brand. The fact is that the overall financial performance is not great. It is fair to assume that Dior is quite profitable. This being the case, it is also fair to assume that some of the other brands are probably having difficulties.

Procter & Gamble Prestige Products division is the result of direct launches (Hugo Boss and Laura Biagiotti), the purchase of the German group Wella (Gucci, Rochas, Montblanc, Escada, and others), and additional purchases (Lacoste, Patou, and Dolce & Gabbana). In addition to having some of the best brands in the market, it also has less sophisticated brands, such as Naomi Campbell and Gabriela Sabatini. The division is based in Geneva and does not publish any figures; sales are included in a very large beauty division, which includes, for example, mass-market shampoos.

Chanel, a private company based in Switzerland, does not communicate any sales or profit data. The business is built largely around the Chanel brand but, in the fashion field, incorporates Holland & Holland and Erès. The group also deals with the Bourjois brand, which is positioned as a middle-market brand in France, but which is higher market abroad.

Puig is a very powerful Spanish group, with many market activities in Spain and Latin America, but is also the owner of Nina Ricci and Paco Rabanne in France, of Carolina Herrera in the United States, and the joint venture partner of Prada for the Prada perfume.

Coty Prestige, based in New York, as well as Paris and Germany, arose from the merger of the Coty Group, always strong in the United States and Australia, and a group of German perfume brands created fifteen years ago by Benckiser as a diversification activity. It has been able to develop or acquire some of the best industry licenses, including Davidoff, Calvin Klein, Lancaster, Jil Sander, Joop, and Vera Wang. It has celebrity perfumes, such as those of Jennifer Lopez and Sarah Jessica Parker, and has licensed Marc Jacobs, designer of Louis Vuitton ready-to-wear, and Chloé from the Richemont Group. This is a rapidly growing private group that is much more involved in perfumes than in cosmetics.

Clarins was created as a skin-care brand in Paris about twenty-five years ago. It has become a very strong group that includes Thierry Mugler Perfumes, which it created, and Azzaro, which it purchased.

Shiseido Europe is the group that started the Issey Miyake and Jean Paul Gaultier brands. It purchased Decleor, with which it has done very well, and Carita, which has been much less successful.

L’Occitane has a very impressive growth rate in the last ten years. Products are sold almost exclusively in their own stores, franchisees, or department stores, with very few products in multibrand stores. It conveys a message of nostalgia and Provence tradition in a rather sophisticated way.

Sisley was created by Hubert d’Ornano after he sold the former family firm, Orlane. It is a private family firm that has developed consistently over the past ten years.

These twelve companies, claiming 50 percent of the total volume, have very strong brands. Only two groups have taken many new licenses and have created a strong base from almost nowhere twenty years ago: Coty, and Procter & Gamble. The French have generally been unable to develop new license deals, with the exception of Inter Parfums (Burberry, Celine, Repetto, and others). However, the company, with sales of €370 million, is still quite small and belongs in the second-tier category.

Is There Room for Outsiders?

In reviewing the very big groups, questions arise as to whether the barrier to entry is too high and if there is actually room for newcomers.

This really all depends on how consumers react to a new product. If the product gets early consumer interest and acceptance at the outset, it can do very well and, as the margins are very high, it is possible to start the business with a very limited cash investment.

But as the risk of failure is very high, companies with limited funds can really afford to launch a brand only once; if they are not successful, they have great difficulty trying a second time.

There are, of course, brands that were launched independently and with limited funds but that still did very well. These include Bulgari, Lolita Lempicka, Kenzo (before it was purchased by LVMH), and MAC (before it was purchased by Estée Lauder), for example.

Key Management Issues

Sophisticated Marketing

Traditionally, marketing perfumes and cosmetics is different from what happens at the mass-market level. For one thing, a perfume can be hated by most people and still be a great success if it is liked very strongly by 3 to 5 percent of the target audience worldwide. To be successful, a perfume must be different, and even if it is perceived as unpleasant by many people, it can still do well. In this industry, products that perform well in open tests and in blind tests are not necessarily strong performers in the marketplace. To take an extreme example, it could be said that the fragrance that would perform best in product tests would be eau de cologne: Nobody would reject it, even if nobody was very excited about it. Product tests must be conducted to see if a perfume has a strong negative or a special weakness that had not been perceived, but the final product decision should never be based on test results alone.

Another difficulty in market tests is that a very great worldwide success may have a penetration of only 4 percent; it is very difficult to find users and to interview them. For example, in considering modifications to the packaging of its Pour un Homme product, Caron decided it would interview French current users, but these constituted less than 0.5 percent of the French male population; to interview two hundred of them, one would have needed an original sample of forty thousand. The company therefore decided to ask a group of perfume stores to take the addresses of those who bought the product and agreed to be interviewed. But, of course, the sample was not really representative either of the total population or of those who used the product.

Unfortunately, because of such limitations target marketing is also quite difficult. Segmentations are difficult to study, to target, and to measure.

Selective perfumes marketing is a bit like fashion marketing. Part of it is top down, in that someone has to decide how the product fits into a given fashion trend at a given time—the bottle, the fragrance, and even the colors of the packaging are not selected by chance. They often result from an analysis of major long-term fashion trends. Asking today’s consumer what tomorrow’s product should be would in fact miss the point.

Nevertheless, market research is a very important aspect of the tactical decisions behind such things as packaging shapes, positioning concepts, advertising execution, or base-line slogan, for example.

Worldwide Advertising and Promotion

Contrary to what happens with mass-market products, consumers of luxury perfumes and cosmetics expect to find the same advertising campaign and the same positioning everywhere in the world. In the mass market, it is possible to adjust positioning and communication to local needs and to local circumstances. In selective perfumes and cosmetics, the same brand platform should apply everywhere.

This does not mean that there should not be specific changes to adjust to one country or another. For example, in Japan, men’s fragrance lines include strong hair products (liquids and tonics), because those products are selling very well and obviously in demand there. In the same way, for a cosmetic line, products must be adjusted to meet the specific needs of Asian customers, American customers, and European customers. In some markets, people prefer jars; in others, they prefer tubes or dispensing bottles. In some markets, the scent should be lighter or almost nonexistent; such adjustments must be made locally, but based on a common platform.

In promotional activities in this category, we have identified three types of countries, leading to large differences. They are as follows:

- Those including Spain, Italy, Argentina, and Brazil, in which small perfumery stores are the most important channel of distribution.

- Those such as France and Germany, where dealing is done through large chains of perfumeries that have centralized purchasing systems and only merchandising activities in the local stores.

- Those such as the United States, Japan, Mexico, and Australia, where department stores produce more than 50 percent of the total volume.

In addition, duty-free operations provide a very large part of worldwide purchases (for perfumes, in particular), with major sales recorded in airport duty-free stores and through in-flight outlets.

For each of these, the promotional plan should be different. For department stores countries, gifts with purchase or purchases with purchases are a very important part of the marketing plan. In countries with large distribution chains, merchandising becomes critical. In duty-free activities, promotional programs must be adjusted as well.

The name of the game is therefore a very strong, generalized marketing platform with specific local adjustments.

Managing Distribution Networks

Almost everybody uses a mix of fully owned subsidiaries, local distributors, and, in some cases, commission agents, and here again marketing programs must be adjusted to these different setups. This subject will be covered at length in Chapter 9.

Organizational Structures

For perfumes and cosmetics, the organizational structure is very similar to what it would be for mass-market products. Marketing and sales staff are crucial for cosmetics products, making training a high-priority activity both for staff operating counters fully owned by the brand and for multibrand sales staff who also need to understand the specifics of each brand’s products and its general brand positioning.

Wines and Spirits

This is the only luxury category in which products are sold in supermarkets (off trade) or in clubs and restaurants (on trade). Duty-free activities are also very important in this category, in some cases accounting for as much as 30 percent of total volume.

Despite these unusual outlets, this is still a luxury business, due to the sophistication of the products and the worldwide market in which it operates. It is also a product category with very strong branding issues; these will be described later.

The Wine and Spirits Market

As mentioned earlier, this market (excluding fine wines) is estimated to be around €33 billion and is characterized by different product types: brown products, essentially Scotch whiskies and cognacs; white products, such as vodka, gin, and rum; and champagne, which is a market all its own.

The Brown Products

This group accounts for approximately €10 billion, split almost equally between the two segments, Scotch and cognac. Though both product categories are fundamentally strong, selling strongly in duty-free outlets and nightclubs, they need to be sold in supermarkets and through wine specialists if they are to build a strong worldwide image.

The cognac market, which continues to do reasonably well in Europe, consists of two distinct strands. The first is the very profitable Asian markets (essentially Japan and China), where it is a status symbol and where people purchase the most aged products, such as XO. Here, though, where cognac used to be the drink of choice with meals, consumers are now turning toward imported wines. The second strand is the large-volume medium-price markets, such as the United States, where there is demand for lower-priced VS (Very Superior) and VSOP (Very Superior Old Pale) products.

Whisky sales have remained steady and have benefited from producers expanding their range of aged-malt products. However, this business is not growing, because its development potential is limited in an era when consumers are looking to mix their spirits with, say, cola, but are reluctant to do so with the brown products.

The White Products

Vodka, gin, and rum each contribute equally to a sales volume of approximately €10–15 billion, with vodka—the preferred drink of the younger generation and good for mixing—experiencing very strong growth. From 1999 to 2003, vodka grew by 40 percent in volume, an average of 9 percent per year. Gin, on the other hand, is declining slightly, but remains a very strong category nevertheless.

Vodka, gin, and rum have another advantage in that there is no aging for such products. In a way, they are ideal marketing products and, given that advertising is limited for all alcoholic products, sound positioning is more important than anything else in creating awareness of, and interest in, the product category. Rum, which is famous as a mixer in drinks, such as the famous Cuba Libre, sells almost exclusively in North and Latin America. Table 3.8 gives the breakdown of the major markets for international rum sales.

TABLE 3.8 Breakdown of International Branded Rum Sales

Source: Le Figaro, 11 January 2007.

| United States | 42% |

| Spain | 10% |

| Canada | 7% |

| Mexico | 7% |

| United Kingdom | 4% |

| Germany | 3% |

| Italy | 3% |

| Asia | 1% |

| France | 1% |

| All others | 22% |

Note: This takes into account only international brands. Local brands, very common in Latin America, are not recorded here.

Champagnes

This is another market of approximately €5 billion. The name Champagne applies exclusively to a product that has been made from grapes from a very small territory around the cities of Reims and Epernay in France. Similar products from any other part of the world must be called sparkling wines. Champagne sales amount to around 320 million bottles per year. Using grapes solely from the Champagne region limits production to a maximum of 360 million bottles. Given this limitation, producers are engaged in a strong movement of trading up and bringing added value to their brands and to their products. As with cognac and whisky, champagne must be left to age, which allows the possibility of blending different wines from different champagne grapes.

More than half of the world consumption of champagne is within France itself, followed by the United Kingdom and the United States.

Other Categories

Other categories, also estimated at about €5 billion, include brandies; liqueurs such as Grand Marnier and Cointreau; specific regional products such as Calvados, Armagnac, Metaxa from Greece, Bols from Holland, and so on; and the biggest of all—tequila.

The Major Operators

The Major Brands

A study conducted every year by Intangible Business in the United Kingdom defines the most powerful spirits and wine brands. This is not done simply on volume or sales but through a complex score that includes:

- Share of market: volume-based measure of market share

- Brand growth: projected growth based on ten years’ historical data

- Price positioning: a measure of a brand’s ability to command a premium

- Market scope: the number of markets in which the brand has a significant presence

- Brand awareness: a combination of spontaneous and prompted awareness

- Brand relevance: the capacity to relate to the brand and the propensity to purchase

- Brand heritage: a brand’s longevity and a measure of how embedded it is in local culture

- Brand perception: loyalty and how close a strong brand image is to a desire of ownership

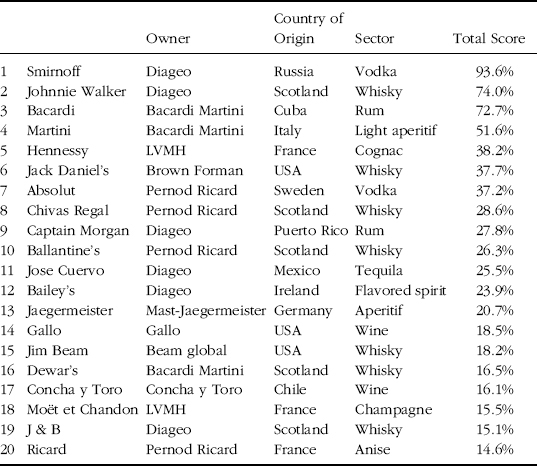

What is striking about the results of this survey (see Table 3.9) is that brands such as Jack Daniel’s, Tequila Cuervo, and Gallo, for example, which are not necessarily known all over the world, still have a very strong clientele and awareness in certain parts of the world.

TABLE 3.9 The World’s Most Powerful Spirits and Wine Brands, 2010

Source: Intangible Business, 2010.

Of this top twenty, eight are whiskies, three are brands of vodka, and two are brands of rum, underscoring the importance of these categories.

Taken purely on volume sold, Smirnoff is the number-one brand (171 million liters), followed by Johnnie Walker. A second vodka, Absolut, follows next, with 117 million liters.

The Major Corporations

Table 3.10 shows the number of brands sold by the larger groups in 2010.

TABLE 3.10 Number of Top Brands Sold by Different Operators

Source: Intangible Business, 2010.

| Number of Brands in Top 100 | |

| Pernod Ricard (France) | 19 |

| Diageo (UK) | 12 |

| Bacardi (Bahamas) | 9 |

| LVMH (France) | 6 |

| Beam Global (USA) | 6 |

| Constellation (USA) | 5 |

| Brown Forman (USA) | 4 |

| Campari (Italy) | 4 |

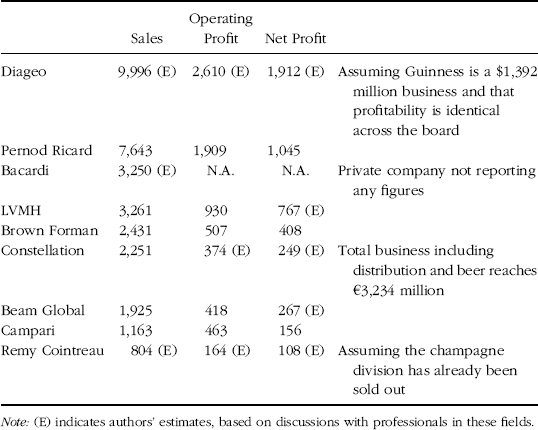

Table 3.11 gives an indication of where these 10 companies stand in terms of size and profitability.

TABLE 3.11 Performance (€ million) of the Top 9 Operators (2010)

Diageo, with twelve brands among the top 100 and huge sales and profit, is the leader in this field. Its top brands include Smirnoff Vodka, Johnnie Walker Whisky, Bailey’s Irish Cream, J&B Whisky, Captain Morgan Rum, Jose Cuervo Tequila, Tanqueray Gin, and Gordon’s Gin. The company is public and is the result of the merger between two already big operators in 1997: Guinness and Grand Metropolitan.

Remarkably, for a very powerful group, Diageo has no major cognac or champagne brand of its own. For many years, first Guinness, then Diageo, have been associated in distribution joint ventures with LVMH, which means that Diageo products are distributed with Hennessy cognacs and some strong LVMH champagne products.

Pernod Ricard started out selling a local product, Pastis, in France. In 2001, it purchased 38 percent of Seagram’s activities and, in 2005, acquired the majority of the assets of Allied Domecq. In 2008, it then acquired Absolut. To complement its traditional Pastis 51 and Ricard brands, it now has a very large number of others with a lot of growth potential. These include Chivas Regal, Ballantine’s, Campbell, and Jameson whiskies; Absolut Vodka; Havana Club, and Malibu rums; Martell cognac; Seagram’s and Beefeater gins; and Perrier Jouët and Mumm champagnes.

Bacardi is a private group, on which there is very little available data. Headquartered in Bermuda, the company is the offspring of a merger between Bacardi Rum and Martini.

LVMH is a very strong business. It has Hennessy cognac in its stable and is a clear leader in champagne (with Dom Pérignon, Krug, Moët et Chandon, Veuve Clicquot, and many others). It has joint distribution ventures with Diageo for a strong worldwide presence. While confining itself largely to the cognac and champagne sectors, in 2005 it acquired Glenmorangie whisky, which may indicate the beginning of a new strategy.

Brown Forman is a public company created in the United States by a pharmacist in Louisville, Kentucky. Its strongest brands are Jack Daniel’s, Southern Comfort, and Tennessee whiskies; Finlandia vodka; and many Californian, Italian, and French wines.

The spirits division of Constellation Brand recorded sales of €2.251 billion. Its beer sales (almost €1 billion) are in a different product category. The company is, nevertheless, the leader in wines, with 240 brands and 25 percent of the U.S. wine market. It is also strong in whisky, gin, and rum, with the Barton brand, in particular.

The wines and spirits arm of Fortune Brands, today called Beam Global, accounts for almost €2 billion of the group’s overall sales of €5.1 billion, spread across many product categories including DIY tools and golf equipment. Its Jim Beam brand is the leading bourbon in the world and, in 2005, it purchased the Courvoisier cognac and Canadian Club Canadian blended whisky brands from Allied Domecq.

Campari is an Italian company listed on the Milan stock market, but still controlled by the founding family. Its products include Campari, Cinzano, Cynar, and a spirit called Sella & Mosca.

Remy Cointreau is the third French group in this sector. It manufactures Remy Martin cognac and Cointreau. It recently sold its champagne brands, Charles Heidsieck and Piper Heidsieck, and the company says it has enough cash to make a major acquisition.

All of the groups described here appear to have considerable financial strength. Almost all are the result of a series of mergers, a process that is certainly not finished. In the last ten years, external growth has been a very large part of everybody’s strategy.

Key Management Issues

Dealing with Mass Merchandisers

The name of the game is to ensure that the product is available on the shelves of local supermarkets everywhere in the world. It must first be sold to very demanding purchasing managers and then carefully managed in the stores by visiting merchandisers. The fact is, though, that a single product cannot afford the cost of this local merchandising effort, making it an absolute necessity to have a local distribution system that can cover its costs by selling many complementary products. The ideal would be to distribute a brand of whisky, a strong vodka brand, a good cognac, and some Champagnes simultaneously. This in itself requires associations between the different brands to be present everywhere.

This is also the case for nightclubs and restaurants, which are very important for image but difficult to reach, and do not necessarily sell large volumes.

Duty-free outlets are very important for creating and maintaining product availability and a strong image for wines and spirits, as they can sometimes reach 30 percent of worldwide volume.

The Need for a Worldwide Structure

Every brand needs to be present and strong everywhere in the world. This often requires joint-venture partnerships such as that between Diageo and LVMH, mentioned earlier. Another such venture, Maxxium, which has now disappeared, was created by Remy Cointreau, Jim Beam (Fortune Brands), Absolut Vodka (Vin and Spirits), and Famous Grouse Whisky (the Erington group, from Scotland). In fact, almost every major operator has, in a given country, one or more of its brands being distributed by a friendly local competitor.

Financing Inventories

A difficult part of this business is the need for ageing the products before they are put on sale. The average champagne must wait forty-four months before it is sufficiently aged to develop its unique bouquet and flavor. For cognac, the average is almost six years and, for certain whiskies, it can be considerably longer. This has a financial cost, which can reach as high as 40 percent of the unit cost of the finished product.

As mentioned earlier, this gives white products a strong advantage, because they do not have to age and therefore have a much better cost structure.

The Need for Pull Marketing

When a product is on a supermarket shelf, it still has to be picked up by the consumer, and this requires that it be known and appreciated. It is the responsibility of the brand to make sure the product does not stay on the shelf. It must be advertised strongly. However, the advertising of wines and spirits has two limitations. In many countries, such advertising is not allowed on television, and is often limited to magazines and billboards.

A second limitation springs from the fact that all products are quite similar and are perceived to be similar by the consumer. The only differentiating element is the perceived content of the brand. This will be discussed later. However, this is without doubt a very difficult marketing and positioning challenge.

Organizational Structures

Just as with perfumes and cosmetics, marketing and worldwide sales are the most important activities in this category. Companies require a large international workforce within distribution companies, either directly or in joint ventures around the world. Here country managers, zone managers, duty-free specialists, and promoters sell the brand, or a selected number of brands, everywhere in the world.

The Watch and Jewelry Market

In this section, we will describe the situation of the jewelry market, then the watch business. In fact, the businesses are similar, but they have different customer expectations and different marketing practices.

The Market

The Jewelry Market

Executives in the field generally estimate the jewelry market to be worth €34 billion. Approximately two-thirds of this is accounted for by nonbranded business, which incorporates the work of all individual family jewelers, who undertake unbranded individual pieces for their customers. Here, products are sold as a function of the weight of gold or silver used in the piece. Precious stones, purchased directly on the open market and valued according to their size, purity, and shape, are often brought by the client to a trusted jeweler, who will mount them in a ring or on a special necklace for a reasonable price.

Family jewelers, who may work across several generations, often manufacture the pieces of jewelry themselves. They may sometimes subcontract the production, but, in every case, they have the trust of their clients and can modify the same piece several times to adapt it to the wishes of different individuals over time.

The branded market is less than half the size (€15 billion) and has a very different setup. The customer usually does not know anybody in the store and the trust comes exclusively from the name that appears over the door. Such stores generally sell standard products and would seldom (except, perhaps, for very wealthy clients) recondition an old jewel or add new stones to a piece.

Customer expectations: Given the price of different jewels and the risk of buying a fake or overpriced product, customers rely on someone they can trust. This trust can come from the brand name of a famous jeweler or from individual contact, with the jeweler acting in a role similar to that of a family doctor.

A large part of the business is undertaken for special occasions. Tiffany, for example, is well known in the United States for its engagement rings. Wedding anniversaries or the birth of a baby, for example, are family occasions when people look for something special, visiting several stores before they decide what they want and where to buy it. The sale of a company or a piece of real estate may prompt others to buy an expensive piece of jewelry. In such circumstances, they generally know what they want and are prepared to visit several stores to get it.

As they buy jewelry, for special or standard occasions, customers expect a very high quality of service from people they feel they can trust. They need to feel that the store cares about them and takes as much time as necessary to satisfy their requirements.

Product ranges: Products can vary greatly, from gold to silver and from products with stones to those without them. Precious stones, such as diamonds, have a set market value, which is known by everybody, everywhere. Producing a diamond ring in the United States to sell in Japan through a local distributor is not that simple, as margins escalate and the final price must still be within a reasonable target. This is why, in fact, gold pieces can be more profitable and provide greater price flexibility.

One jeweler has found a way around this problem. H. Stern, which originated in Brazil, is the specialist in semiprecious stones and brings to the market jewelry pieces with stones such as aquamarine, amethyst, and yellow citrine.

Financial aspects: Pricing is a very difficult subject in this business. For precious stones, there is a limited range of possible retail prices. For gold, there is an official measure of the retail price: the cost per gram. It is possible to visit gold markets in many places. Caracas or Bogota, for example, provide a choice of many small retailers and many jewelry pieces, but the retail price is computed by weight and the different pieces are simply placed on a scale together to get the final price.

A simple way to compare the pricing level of the different jewelers would be to list their price in dollars per gram of gold. However, the major brands refuse to do this. They do not see themselves simply as sellers of gold but, rather, of artistic objects, for which the work required varies from one piece to another and the time and skills involved cannot be compared.

Also, at the brand’s headquarters, the difficulty is to ensure that the global margin can be divided between the workshop where the piece is made by specialist craftsmen, the marketing and promotion, the distributor, and the final retailer or department store.

The Watch Market

The value of this market is considered by professionals in the field to be around €11 billion. It is more heterogeneous than the jewelry market and differs from it in market segments, gender, and nationalities.

Combination watches or upscale watches have individual movements and, of course, no quartz batteries. They have a movement that is generally handmade and can be self-winding. They are called combination watches because of the combination of features they offer, such as time, date, situation of the sun and the stars, or the seasons. They often also have a chronograph function. Sometimes, such watches are produced as a single unit or in very limited numbers, commanding prices of up to €200,000.

Jewelry or specialty watches are less sophisticated and are manufactured in larger numbers. In this category, we have put all watches that sell for between €1,000 and €5,000 wholesale. Most are beautifully made objects, sometimes powered by quartz batteries, and are ideal expensive gifts.

Fashion or mood watches belong to a third category. Here, we have put those watches that sell at retail from €100 to €1000. These include Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, and Armani watches. The idea in this category is to promote the concept of owning several watches that can match the customer’s changing moods.

Men or women?: Watches are one of the few luxury products that men can buy and cherish. Probably 90 percent of combination watches are purchased by men, many of whom collect old models as they would collect expensive stamps.

Women are important in the second segment as they purchase or are given expensive watches for special occasions. They are also the largest segment of buyers of fashion and mood watches.

Which nationalities?: Two markets must be singled out. China is a very big market for watches. Chinese men traditionally are buyers of luxury products, and expensive watches are taken to be a sign of business and financial success. In Europe, Italians buy more watches than anyone else and have been known to line up outside a Swatch store the night before a limited-edition model goes on sale. They believe that wearing an expensive, well-known watch is the ultimate in elegance and sophistication.

Other important markets are Japan, which is similar to China, though to a lesser extent, and the United States, where customers buy both mood watches and more expensive brands, which for many women can become sophisticated conversation pieces.

Watches are also a very important part of men’s status and dress codes in Latin America, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Preferences vary around the world: Europeans generally wear their watches with a leather strap; in Asia and tropical countries people prefer steel bracelets.

The Major Operators

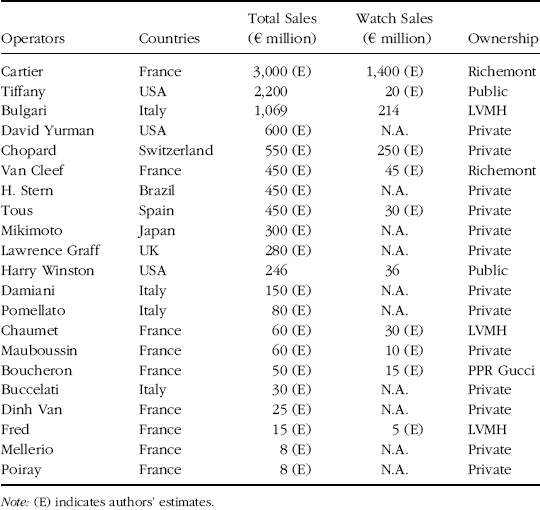

The Jewelry Brands

Table 3.12 shows our estimates of the total sales and of the watch sales of the major operators in the sector. For example, watches account for approximately half of Cartier’s total business. For Van Cleef, the figure is 11 percent of sales, and, for Tiffany, only 1 percent. However, it is not possible to arrive at the jewelry sales by simply subtracting the watch sales from the total, because for Cartier, for example, the total sales include scarves and leather goods, and those of Bulgari also include perfumes. What can also be seen from Table 3.12 is that only eleven operators have a major and meaningful level of activity. Some of the highlights are presented here.

TABLE 3.12 Estimated Sales (incl. watches) of Major Jewelry Operators, 2010/2011

Source: Annual reports and discussions with specialists of the sector. We decided not to put Chanel and Dior in this table as our estimates of their sales were too uncertain.

- Cartier is the largest brand and an extremely profitable one. It is extremely strong in watches, but has also been able to develop an important jewelry business. It is very strong in Europe and Asia and is an important operator in the United States.

- Tiffany is almost as big as Cartier in jewelry, but not very strong in watches. In 2008, they reached a watch licensing agreement with the Swatch group, but it was cancelled in September 2011, and Tiffany must now start again from square one. Its strengths are in the United States, where it is clearly the leader, and in Asia. It is now trying to move into Europe. Tiffany is well known in the United States for its diamond engagement rings, but in the United States and Asia, in particular, it is also known for such items as ballpoint pens, silver-plated baby spoons, and christening medals with low entry prices of less than €75.

- Bulgari, based in Rome, is a strong performer that, from its beginnings as a silversmith, has moved slowly into jewelry and watches. It is also quite strong in perfumes, has a very effective collection of ties and scarves, and is quite active in leather goods. It sold the majority of the company to LVMH in January 2011.

- David Yurman, almost unknown in Asia, and moving slowly into Europe at the beginning of 2011, is a very strong and much-respected American retailer.

- Van Cleef & Arpels, the second jewelry brand of the Richemont Group, has known a very fast growth in the past five years. It has become a strong brand, very active in high-end jewelry products, but which could still develop a strong watch business.

- Chopard, a family firm based in Geneva, operates 100 stores around the world and has a very impressive performance, primarily as a jeweler but also as a watchmaker. Its happy diamond line is well known and well respected.

- H. Stern was created in Brazil in 1945 by Hans Stern, who is still running the show. Specializing in semiprecious stones, it now has some 160 stores, mostly in Latin America, but with boutiques in the United States and Paris.

- Tous is somehow a different animal, but its extremely strong growth and its creative low-price gold pieces make it an interesting case.

- Mikimoto is the leader in cultured pearls, which it develops in Japan. Gradually, though, it has broadened its range to incorporate interesting jewelry collection pieces.

The Watch Brands

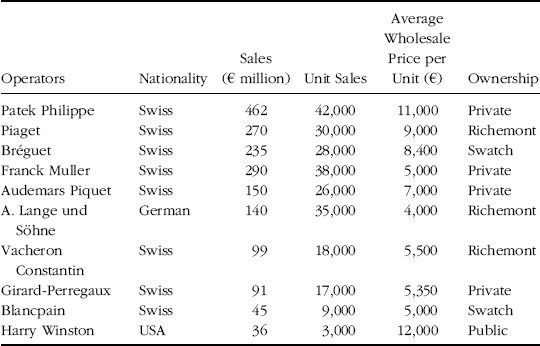

Again, we classify the operators into three different categories, according to their price segments. While industry specialists might object that this segmentation is somewhat artificial, it has the advantage of distinguishing between brands that are different in style and in size.

Table 3.13 shows the major operators in combination and very expensive watches. In this category, where the total sales of the leading ten operators are €1.7 billion out of a total market in the region of €2 to 2.5 billion, almost everybody is Swiss. For these very expensive pieces, the business is run from Switzerland, even though the consumers are scattered around the world. Some of these brands are still independent, but half of them belong to Richemont or to the Swatch Group.

TABLE 3.13 Estimated Sales of Combination/Upscale Watch Operators, 2010

Source: Business Montres, 2011.

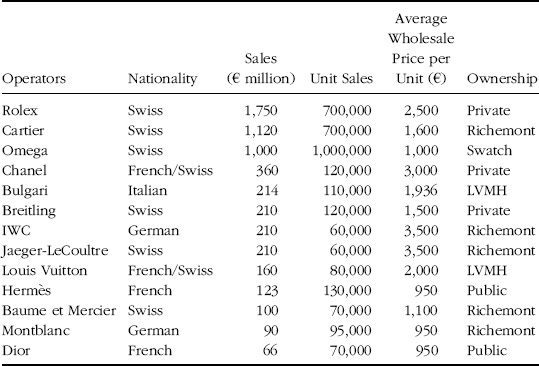

Table 3.14 presents the jewelry and specialty watch operators.

TABLE 3.14 Estimated Sales of Jewelry and Specialty Watch Operators, 2010

Source: Business Montres, 2011.

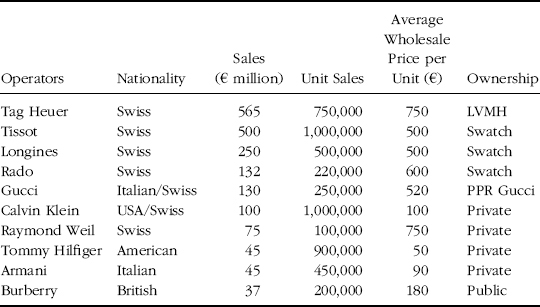

Table 3.15 presents the last group of watches, which are still luxury watches, but with an average wholesale price below €900. This category is not particularly homogeneous in that it contains brands such as Tag Heuer and Rado, which could be considered as belonging to the second category, and others such as Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, which have completely different positioning and retail prices around €100 to 200.

TABLE 3.15 Estimated Sales for Fashion and Mood Watch Operators, 2010

Source: Business Montres, 2011.

The lesson to emerge from this segmentation into three categories is that they are three different businesses: one where units sold are measured in thousands, another where units sold range from 50,000 to almost a million, and a third where figures are measured in the hundreds of thousands.

We said earlier that total sales in the upscale segment were probably above €2 billion. In the jewelry and specialty watches segment, total sales are probably around €7 billion. In the last category, the fashion and mood segments, even if the unit figures are impressive, the overall sales level—also at around €2 billion—remains limited.

It is also interesting to note that aside from Cartier, Bulgari, and Harry Winston, the jewelry brands remain relatively small in the overall watch business. If watches are very important to enable a jewelry brand to develop, to reach break-even in existing stores and to finance new ones, the watch business stands on its own, is almost always Swiss made, and is developing rapidly.

In this business, three groups dominate the market: Swatch leads, with a 25 percent market share; Rolex, with 22 percent, is second, standing on its own brand and with its lower-positioned brand Tudor (with sales of €78 million); then comes the Richemont Group, 20 percent, which includes Cartier and many other brands. Despite this combined share of 67 percent, the market is also open to newcomers that can develop a good idea or a special skill.

Key Management Issues

Retail versus Wholesale

While for jewelry a large part of the business is done at the retail level, for watches most of the business is done at wholesale, as the products need visibility and a strong presence at different points of sale.

At one time or another, brands such as Ebel, dealing mainly in watches, have tried to open retail stores, without much success. Nevertheless, brands like Rolex and Omega have been successful in this. Others have tried to sell their watches only in their own jewelry stores. This was the policy adopted at the outset by Bulgari watches, but the company quickly realized that it had to enlarge its distribution to create interest in the product.

Then, as their wholesale activities flourished, jewelry brands have been tempted to enlarge their distribution with multibrand stores. However, unless they could come up with a very specific product line, this has not always been effective. Cartier had Les Must de Cartier for many years, but while this was probably very useful for building the brand at the beginning, it was removed from the catalog in 2007, then brought back in 2010, probably to face the post-2008 crisis, then removed again. Bulgari has a small jewelry line for multibrand jewelry stores. Tiffany has never done it and is unlikely to do so in the near future.

Pricing and Product Lines

For jewelry, there are different customer segments: those ready to spend up to €5,000 for a small piece, those who are prepared to spend between €5,000 and €50,000, and those who are looking for exclusive pieces selling above that amount.

Different jewelers are often lacking in their offerings in one or another of these segments and are obliged to hire new designers and to develop specific skills to work on overcoming this lack.

For a given brand of watches, on the other hand, there should be only one price range, but this requires strong commercial and marketing work.

The Risk of the Major Customer

Exclusive brands such as Mauboussin, Asprey, or, at one point, Chaumet, were heavily reliant on major orders from the likes of the Sultan of Brunei or the King of Morocco if they were to meet their annual sales budgets. When these very big orders arrive, everything is rosy and life is easy. What would happen if, for one reason or another, a major customer did not place an order for the following year? As in every business, diversification and balance in the client list are very important parts of a healthy business.

Organizational Structures

In the jewelry business, the organizational structure is generally limited to a retailing manager and an export manager; a design office and a production workshop; and a comparatively large marketing team to deal with product positioning, brand positioning, and public relations.

The Leather Goods Market

We spoke earlier of all fashion accessories but, for this section, we wanted to concentrate exclusively on leather goods. Sometimes this definition also includes shoes, but here we have decided to keep the shoes out of our analysis. For shoes, we consider the manufacturing processes and the commercial challenges to be quite specific. Therefore, we will not speak about them.

The Market

The world market, at a mix of retail and wholesale, corresponds to approximately €22 billion. It can be divided in three major segments: ladies’ handbags, luggage, and small leather goods.

Ladies’ Handbags

Ladies’ handbags are a fashion accessory and part of a woman’s total look. Actually, the effect of a beautiful dress or an impressive woman’s suit can be ruined if worn with a cheap plastic handbag or bag made of low-quality leather. A brand-new, sophisticated dress can lose its fashionableness and its freshness if it is combined with an old, outdated, and shapeless handbag. This is very obvious for the Japanese, the Italians, the Chinese, and the Americans, but it is not always perceived in the same way by French consumers. On the contrary, a brand-new, stylish handbag can freshen a slightly outdated dress and give it additional style. The price of a luxury handbag can be around €200 to €2.000, so it is much less expensive than a sophisticated fashion dress, and has a much longer life.

Luggage