12.3. MAKING TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION OPERATIONAL

Strategic choices provide broad guidelines for the extent, type, and approach to innovation that an organization intends to pursue. Making these choices operational, however, requires the design and implementation of a process for harvesting ideas, deciding which ones warrant further investment, and developing and launching those that do. An innovation process integrates R&D with value creation, and facilitates communication among varied constituencies over time, both within the organization and between the organization and its environment. The process needs to be disciplined but not constraining, and be inclusive without paralyzing decision making. More ideas are often generated than can be pursued in an organization. The challenge is to find ways to select and build on those ideas that are most consonant with the organization's strategic choices.

While the importance of evaluating new ideas in order to increase their chance of commercial success is well recognized, there is no consensus on the one best way to accomplish it (Wind and Mahajan, 1997; Rangaswamy and Lilein 1997; Ozer, 1999; Hobday, 2005). Several elements are common to most approaches: generating and then initially screening ideas, evaluating ideas, research and development, scale-up, financing, market development and launch (Rogers, 1995; DeSouza et al., 2007). However, the manner in which these elements are organized and managed differs. Table 12.3 compares two innovation process models in terms of the manner in which projects are reviewed, the sources and roles of reviewers, and the teams involved as projects are developed. One model is characterized by sequential feedback as an idea develops; the other is characterized by an iterative process that integrates multiple viewpoints as an idea develops. The two models have important implications as to how much project redirection/reframing is allowed to occur as ideas are developed.

| Sequential-Feedback Model (Stage Gate, Funnel)[] | Integrative, Iterative Model (Venture Board, Learning Plan)[] | |

|---|---|---|

| Review Procedure | Focus is on uncertainty reduction over time. | Focus is on reframing the idea through iterative discussion. |

| Follows explicit, standard set of sequential stages, mainly related to functions. Though feedback among stages may occur, each stage is viewed as a hurdle or gate a project must pass over/through in order for development to continue. | Discussion process is ongoing among review board members and project team throughout the life of projects. Stages are related to level of project development, and are treated as interdisciplinary throughout. Stages are viewed as opportunities to set and review milestones; identify assumptions and risks; and to guide, reframe, and augment project ideas as appropriate. | |

| Review Criteria | Review criteria are explicit, often functionally based, and change over the course of the project. | Review criteria are interdisciplinary, and are tailored to the type and level of development of the project. Emphasis is placed on qualitative measures or milestones especially for projects centered on emerging technologies. |

| Reviewers | Reviewers are typically functionally based managers from inside the organization, and change as projects reach successive stages. | Review board members may be drawn internally or externally, and are chosen on the basis of experience and insight into new venture development; the board remains essentially intact throughout the lifetime of projects. Project leaders and team have input into iteration/reformulation. |

| Project Team | Team members are likely to change as projects reach successive stages. | Team may remain intact though, depending on project needs, additions/deletions may be made. |

| Advantages | Process is relatively systematic and standardized. Criteria are clear and easy to communicate. | Process allows projects to develop organically versus being subject to standard external criteria. Review is multidisciplinary throughout, though different dimensions may be emphasized as needed as a project proceeds. |

| Disadvantages | In practice, process can become functionally based versus multidisciplinary. Opportunities for feedback and iteration may become lost. External review process and established criteria may favor projects that fit into an organization's existing business and thus favor incremental innovation with shorter term payback and stifle radical innovation. | In practice, process can be costly and time consuming. Iteration can turn into indecisiveness. |

| External review by management may become demoralizing to innovators. | ||

| [] [] | ||

[] Cooper and Kleinscmidt, 1986; Davila et al, 2006

[] Davila et al, 2006; Rice et al, 2008.

12.3.1. Sequential Feedback Model

The sequential feedback model is comprised of a series of successive steps in which concepts are weeded out over time on the basis of sets of technical and commercial criteria. While ideas progress through discrete, sequential, functionally related stages (e.g., market, financial, etc.), some feedback between stages can occur. Cooper and Kleinschmidt's 13-step process provides a widely recognized example (Table 12.4). The sequential-feedback model is explicit and standardized, and thus has the benefit of clarity—people know the criteria upon which a project idea will be judged. It is streamlined and efficient at implementing new ideas, and focuses on reducing uncertainty as ideas are developed. While the sequential-feedback model is functionally based, it can incorporate market factors throughout and, in fact, Cooper's model recommends this.

There are risks, as well. In practice this approach is more likely to fall into the trap of functional sequential review and thus lack interdisciplinarity and feedback over time. Too much rigor and external review by managers can be applied early in the process, which dampens creativity. As Amabile (1998) warns, applying time-consuming layers of evaluation to new ideas undermines intrinsic reward via external evaluation and fear. Projects based on emerging and radical technology that cannot demonstrate payback, a clear market segment, and so on are likely to be discarded in favor of more certain projects. Thus, the process in practice tends to favor more incremental initiatives. Once a project is decided on, and as investment increases, the emphasis on commercialization may override opportunities to make changes in the technical or market aspects of the project.

| (1) Initial Screening of Ideas via a formal checklist or informal discussion |

| (2) Preliminary Market Assessment via secondary data on trends, review of competing products, informal customer contact |

| (3) Preliminary Technical Assessment to identify merits and challenges |

| (4) Detailed Market Study/Market Research using formal data collection and analytical techniques, such as surveys |

| (5) Business/Financial Analysis leading to go/no-go decision; based on formal or informal sales and cost estimates, cash flow analysis, ROI analysis, payback period |

| (6) Product Development resulting in a prototype |

| (7) In-House Product Testing under controlled conditions |

| (8) Customer Tests of Product in the field |

| (9) Test Market/Trial Sell to a limited set of customers |

| (10) Trial Production to test manufacturing method |

| (11) Pre-commercialization/Business Analysis that provides in-depth plan for marketing, producing, organizing, business |

| (12) Production Start-Up on a commercial scale |

| (13) Market Launch |

These drawbacks can be overcome in part by ensuring that the people judging the projects in the early phases recognize that the concepts should not be subject to the same rigor—for example by applying stringent criteria like discounted cash flow—as more fully developed projects, and thus are open to less developed and higher risk projects with higher potential (Utterback, 1996, p. 226). Moreover, new information should still be allowed to flow into the process as the product and market are developed and clarified.

12.3.2. Integrative-Iterative Models

Integrative-iterative models are aligned with venture board and learning plan models. In comparison to the sequential feedback approach, this approach to innovation is more organic. The review process is best described as "developmental" as opposed to "weeding out," and is multifunctional throughout. In contrast to explicit technical and market criteria, in the integrative-iterative approach team projects are judged on the basis of the experience and instinct of a venture team which contributes at the early stage of investment and focuses on discussion and collective interpretation (Davila et al., 2006; Anthony et al., 2008). The venture team typically comprises internal as well as external experts. While milestones are established early on to judge progress, this process focuses on building on and reframing ideas through iterative discussion.

For long-term projects that are at the extreme pole of uncertainty, Rice (2008) has proposed "The Learning Plan," which is appropriate for breakthrough projects in which the outcome is highly uncertain in technical, market, organizational, and resource dimensions; and projects with a lifetime of 10 years or more and for which even milestones are difficult to set. Their framework emphasizes that the team undertake an ongoing process of systematically examining the sources of uncertainty and test assumptions along the course of a project. In reviewing what has been learned, directions are adjusted accordingly. The board comprises people with experience in high-uncertainty projects along all dimensions.

The integrative-iterative approach typically allows for more iteration as projects develop, and more ongoing input from the venture team. Moreover, while the venture board is multidisciplinary throughout, specific target markets are normally identified later in development, and financial measures are also applied later. Thus this approach is particularly suitable to radical innovation, in which technical development is nascent and markets are undeveloped or even unknown. The venture model places emphasis on the volition of the project leaders and members in successfully developing and implementing innovation. The integrative iterative model also is most open to external networks as outsiders are often included on the board.

The integrative-iterative model has downsides. It can be time consuming and costly. It can tend to get trapped in a cycle of iteration and multiple so that no direction is chosen and implemented. At some point, for investment to continue, the uncertainty in the project must be reduced. Because the process is adapted to the unique needs of a project, the criteria used are not explicit and people may not have a clear understanding of why some projects are developed over others. To overcome these drawbacks, the review board can help guide the project team toward decision making versus supporting an endless cycle of iteration, and can encourage the project team to identify and clarify market targets and technical approaches as these become evident. In addition, people within the organization need to be educated in how to access and contribute to the process of iteration.

12.3.3. Which Approach Is Best?

In a nutshell, the sequential-feedback model emphasizes value capture over creativity, while the integrative, iterative model emphasizes creativity over value capture (Davila et al., 2006). The major implications of the two models are that with the sequential model openness to project redirection once selected is less, and decreases over time. With the integrative, iterative model openness to project redirection/reframing is emphasized throughout development.

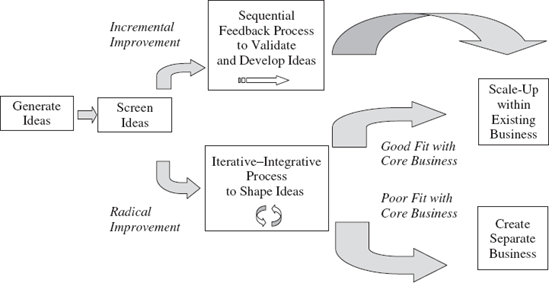

The question is not which model is best, but which model or models best fit an organization's strategic objectives for innovation. If an organization wants to encourage both incremental innovation as well more radical innovations that may be disruptive to it, Anthony and colleagues (2008) recommend using dual pathways for the innovation process. A sequential feedback model would be appropriate for incremental innovation, and the integrative-iterative model would be most appropriate for radical or disruptive innovation (Figure 12.1). Initial screening is clearly a key decision point in the innovation process. If a potentially disruptive innovation is sent through the sequential model, it will likely be killed prematurely or forced into the pattern of the existing core. Therefore, during initial screening, new project ideas should be divided loosely into incremental "core improvements" (an improvement or logical extension) or potentially radical "new growth" (the project idea is in its early stages, is uncertain, and runs the risk of disrupting the core initiatives). Core improvement ideas are sent through a validation and scaling process that is aligned with the sequential-feedback approach in which uncertainty reduction starts early. The iterative-integrative approach is more appropriate for developing new growth opportunities. Once a new growth idea is couched in a business model (i.e., once technical and market directions are clearer), it can be brought back into the existing organization if appropriate; if not, a separate entity should be created that allows the new venture to develop outside organizational constraints.

Figure 12.1. Pathways for Incremental and Radical Innovation (Adapted from Anthony et al., 2008)