16.7. APPLYING A STRATEGY PROCESS

As has been emphasized throughout this chapter, strategic management is a multifaceted process for which many models and tools have been developed for organizations. While there is no one way to craft a strategy, it is fair to say that several activities are common to most strategy processes:

Develop the mission statement, which, in combination with the long-term strategic objectives, expresses the organization's vision, philosophy, and deeper purpose.

Identify trends, potential opportunities and threats. Include information about external trends based upon environmental scanning; identify major potential opportunities and threats that are likely to affect the activities and the mission of the organization.

Identify strengths and weaknesses. Delineate inherent competencies and emerging deficiencies.

Strategic objectives. This would include (mostly quantifiable) objectives the organization as a whole would like to achieve within a certain time horizon.

Policies. This regards the general guidelines within which the organization operates, and are often associated with functions or other recognizable areas within an organization.

Critical success factors. Describe overarching dimensions crucial for organization success.

Specific actions. These are specific activities and programs the organization needs to undertake to reach each of the goals and objectives.

Resource Allocation. This would include allocation of resources and the determination of performance metrics for management control.

Who should be involved in this process? Including participants from throughout the organization—and from relevant external stakeholders if appropriate—ensures that a variety of insights is mined. Moreover, people who are involved in the process understand best how to implement it and to communicate to others the direction and expectations of the organization. In small organizations—those with twenty people or fewer—everyone can and should participate. However, in larger organizations this is not possible, and it's necessary to involve representatives of various parts of the organization.

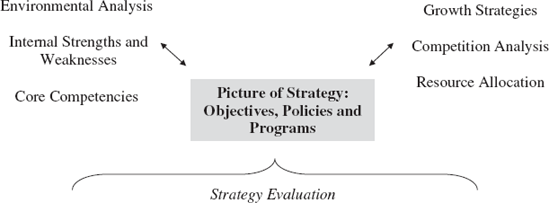

Figure 16.1 provides a visual representation of a strategy process, which can be adapted to organizations of many types—academic, government, and industrial—and at various stages of development. For example, an organization that has a longstanding mission statement might want to begin by reviewing this statement and then proceed to an environmental analysis. A brand new organization might start the process with an environmental analysis, and then proceed to internal strengths and weaknesses prior to mission development. In all cases, it is important to keep in mind that the process is iterative—the activities constantly influence one another. Implementation of strategy, of course, also influences formulation. Practically speaking, however, one has to start somewhere in the process. Each of the elements is described further in the following sections.

Figure 16.1. Major Elements of a Strategy Process

16.7.1. Environmental Analysis: Generation and Prioritization of Trends

In this stage, participants are asked to generate quantitative and qualitative trends over a given time frame, which are related to the various dimensions and geographic scopes (Table 16.3). This chart helps ensure that all areas of the environment are considered. Once trends are identified, discussion should surround whether they represent opportunities or threats (or both). If numerous trends surface, it may also be necessary to prioritize trends as to the degree of their impact and probability of occurrence.

A small sample of some trend areas to examine may include:

National and international security issues

Changing world order

National policies related to climate change, stem cell research, and so on

Customer dynamics

Level and type of investment in science and technology

Population, family structure, and other demographics

Interest rates changes, and availability of capital

The natural environment

Human health and welfare

Educational levels

Workforce demographics

Trends towards public-private partnerships

16.7.2. Strengths and Weaknesses Analysis: Generation and Prioritization

Next, participants are asked to identify the organization's strengths and weaknesses in various areas, as outlined in Table 16.4.

| Economic | Technological | Socio-cultural | Political/Legal/Regulatory | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | |||||

| Nation | |||||

| World |

16.7.3. Core Competency Analysis

Once identified, an organization's unique strengths—including skills and knowledge sets—can be combined into core competencies that create long-term value for the customer (Quinn and Hilmer, 1994). As mentioned earlier in the chapter, these competencies should be ones in which the organization can dominate, are adaptable, durable, and are embedded in the value and managerial systems.

16.7.4. Developing a "Picture" of Strategy: Mission, Strategic Objectives, Policies and Programs

An organization's strategy emerges in the course of determining how an organization's combination of major strengths can be leveraged to take advantage of key opportunities and mitigate threats in the environment; and how to strengthen major weaknesses. A framework for capturing strategy is provided in Table 16.5. Included in this "picture" of strategy are the objectives, policies, and programs that can be used to communicate the organization's future directions. Note that under policies a list of areas is provided. This is not meant to be exhaustive; nor do these apply to all organizations. The point is that typically there are general guidelines or goals that need to be established so that people know the boundaries within which they are expected to operate.

| Objectives What is to be Achieved, and Why | Policies General Guidelines (within areas) | Programs Step by Step Action Sequences (within areas) |

|---|---|---|

| Mission

Strategic Objectives Long term Transcends Functions Often but not always quantitative | Finance

Accounting Human Resources Production R&D Innovation Marketing Management Growth Acquisition Globalization Others? | Finance

Accounting Human Resources Production R&D Innovation Marketing Management Growth Acquisition Globalization Others? |

A word of caution is necessary regarding quantifying objectives, policies or programs. While it is desirable to provide concrete targets to which an organization can judge its progress and hold itself accountable, overemphasis on numerical goals and rigid deadlines may undermine the very objectives the strategic plan intends to achieve. As strategy is developed, care must be taken to avoid the establishing of trivial goals and exaggeration or even falsification of results achieved such that targets appear to be met.

16.7.5. Growth and Competition

The dynamic nature of R&D intensive enterprises means that addressing growth is an ever-important topic. The blue ocean strategies discussed Section 16.5 lead organizations continually to seek new products and new markets, in short, to be pioneers.

Pioneering does not imply ignorance of competitive forces. But the point in time in which competition enters into the picture of strategy is key. A novel approach is more likely when a picture of strategy is developed that:

Looks at how this stacks up against competitors.

Focusing on competition too early—consciously or not—may well lead to imitation.

16.7.6. Resource Allocation

In the absence of resources, even the best-formulated strategy is doomed to failure. Thought must be put into the specific types and amounts of financial, physical, and human resources needed to fulfill an organization's picture of strategy. What weaknesses in resources surface in the analysis above require strengthening?

16.7.7. Evaluation

Finally, an organization's picture of strategy needs to be evaluated. Again, the elements in Figure 16.1 are iterative: strategic thought and action are deeply intertwined. Focusing on Rumelt's four critical flaws on an ongoing basis—consistency, consonance, advantage, and feasibility—ensures that strategy is continually revitalized.

Keeping the strategy and the strategy process fresh is among the major challenges faced by leadership. In Dilbert's world, the cynicism arises because the process itself—the dreaded annual retreat—becomes the focus, not the substance of strategy. Leadership must center the process on the very real opportunities and threats faced by organizations and the individuals who comprise them. The reason the term "picture" is used rather than "plan" is that plan connotes a bulky document that gathers dust. Weick (2005), in fact, prefers to see the strategy process as akin to an impressionistic painting, in which there is "enough structure to guide, but not so much as to stifle and confine." The ideal approach to strategy may be that expressed by Peters and Waterman in their modern classic, In Search of Excellence (1982:75–76).

"The stronger the culture and the more it was directed toward the marketplace, the less need there was for policy manuals, organization charts, or detailed procedures and rules. In these companies people way down the line know what they are supposed to do in most situations because the handful of guiding values is crystal clear."