8.1. IDENTIFYING YOUR LEADERSHIP STYLE

In characterizing the behavior of their supervisors, subordinates used similar ideas—for example, bossy or structured versus people-oriented or considerate. Similarly, when leaders are questioned, some claim that they pay attention to people and others say they focus on the task.

As it turns out, however, the distinctions are not so clearly drawn. Extensive research by Fiedler (1967, 1986a) found that some people are task-motivated when they are relaxed but person-motivated when they are under stress, while others show the opposite pattern—that is, they are person-motivated when relaxed and task-motivated when under stress. It might be useful to find out for yourself what kind of leader you are. To do that, look at Fiedler's instructions in "Identifying Your Leadership Style" (Fiedler et al., 1977), which is included in this section.

You can score your own Least Preferred Co-Worker test. If your score was 64 or more on that test, Fiedler's evidence is that you are person-oriented under stress and task-oriented when relaxed. A score of 53 or less is evidence that you are task-oriented under stress and person-oriented when relaxed. If you got more than 64, you are a high LPC (least preferred co-worker); and if you got less than 53, you are a low LPC. If you scored between those two numbers, Fiedler's data do not have anything to tell you about your leadership style.

Fiedler argues that people are difficult to change, and that it is easier to change the situation in which people find themselves than to change the people. At least for routine, everyday behaviors that are normally under habit control, people act in ways over which they do not have much control. So rather than change themselves they should try to change their leadership situation. Fiedler has provided us with ways to measure the situation. In this section you will find the Leader–Member Relations Scale, the Task Structure Rating Scale, and the Position Power Rating Scale. You can answer these scales and score them by following the instructions on the forms. Next comes the Situation Control Scale. Follow the instructions and find your score. If your score is 51–70 you have high control; if it is 10–30 you have low control. Fiedler and others have done literally hundreds of studies linking LPC and the Situational Control Scale on the one hand, and group effectiveness (profits, high productivity, speed in getting the job done, accuracy) on the other hand. The findings from these studies fall into a pattern. It turns out that low LPCs do well in situations in which they have either high or low control, but do not do well in situations where they have intermediate control. On the other hand, high LPCs do well in situations where they have intermediate control. So, first find out how much control you have in your particular job situation.

Identifying Your Leadership Style[]

[] This material is from F. E. Fiedler, M. Chemers, and L. Mahar, Improving Leadership Effectiveness: The Leader-Match Concept. Copyright 1977 John Wiley & Sons. Reprinted by permission of the author and publisher.

Your performance as a leader depends primarily on the proper match between your leadership style and the control you have over your work situation. This section will help you identify your leadership style and the conditions in which you will be most effective. Carefully read the following instructions and complete the Least Preferred Co-worker (LPC) Scale.

INSTRUCTIONS

Throughout your life you have worked in many groups with a wide variety of different people—on your job, in social groups, in church organizations, in volunteer groups, on athletic teams, and in many other situations. Some of your co-workers may have been very easy to work with. Working with others may have been all but impossible.

Of all the people with whom you have ever worked, think of the one person now or at any time in the past with whom you could work least well. This individual is not necessarily the person you liked least well. Rather, think of the one person with whom you had the most difficulty getting a job done, the one individual with whom you could work least well. This person is called your Least Preferred Co-worker (LPC).

On the scale below, describe this person by placing an "X" in the appropriate space. The scale consists of pairs of words which are opposite in meaning, such as Very Neat and Very Untidy. Between each pair of words are eight spaces that form the following scale:

Think of those eight spaces as steps that range from one extreme to the other. Thus, if you ordinarily think this least preferred co-worker is quite neat, write an "X" in the space marked 7, like this:

However, if you ordinarily think of this person as being only slightly neat, you would put your "X" in space 5. If you think of this person as being very untidy (not neat), you would put your "X" in space 1.

Sometimes the scale will run in the other direction, as shown below:

Before you mark your "X," look at the words at both ends of the line. There are no right or wrong answers. Work rapidly; your first answer is likely to be the best. Do not omit any items, and mark each item only once. Ignore the scoring column for now.

Now go to the next page and describe the person with whom you can work least well. Then go on to the following pages.

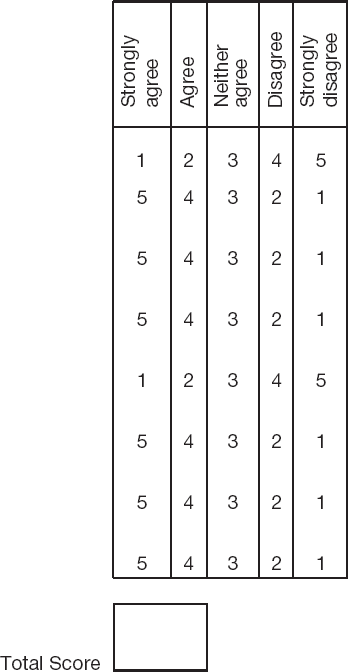

LEADER–MEMBER RELATIONS SCALE

Circle the number that best represents your response to each item.

The people I supervise have trouble getting along with each other.

My subordinates are reliable and trustworthy.

There seems to be a friendly atmosphere among the people I supervise.

My subordinates always cooperate with me in getting the job done.

There is friction between my subordinates and myself.

My subordinates give me a good deal of help and support in getting the job done.

The people I supervise work well together in getting the job done.

I have good relations with the people I supervise.

TASK STRUCTURE RATING SCALE—PART I

| Circle the number in the appropriate column. | Usually True | Sometimes True | Seldom True |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the Goal Clearly Stated or Known? | |||

| 1. Is there a blueprint, picture, model, or detailed description available of the finished product or service? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 2. Is there a person available to advise and give a description of the finished product or service, or how the job should be done? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Is There Only One Way to Accomplish the Task? | |||

| 3. Is there a step-by-step procedure, or a standard operating procedure that indicates in detail the process that is to be followed? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 4. Is there a specific way to subdivide the task into separate parts or steps? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 5. Are there some ways that are clearly recognized as better than others for performing this task? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Is There Only One Correct Answer or Solution? | |||

| 6. Is it obvious when the task is finished and the correct solution has been found? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 7. Is there a book, manual, or job description that indicates the best solution or the best outcome for the task? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Is It Easy to Check Whether the Job Was Done Right? | |||

| 8. Is there a generally agreed understanding about the standards the particular product or service has to meet to be considered acceptable? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 9. Is the evaluation of this task generally made on some quantitative basis? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 10. Can the leader and the group find out how well the task has been accomplished in enough time to improve future performance? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Subtotal  | |||

TASK STRUCTURE RATING SCALE—PART 2

Training and Experience Adjustment

NOTE: Do not adjust jobs with task structure scores of 6 or below.

(a) Compared to others in this or similar positions, how much training has the leader had?

(b) Compared to others in this or similar positions, how much experience has the leader had?

Add lines (a) and (b) of the training and experience adjustment, then subtract this from the subtotal given in Part 1.

Subtotal from Part 1.

Subtract training and experience adjustment

Total Task Structure Score

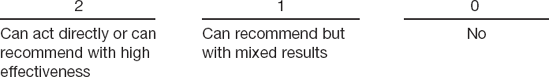

POSITION POWER RATING SCALE

Circle the number that best represents your answer.

1. Can the leader directly or by recommendation administer rewards and punishments to his subordinates?

2. Can the leader directly or by recommendation affect the promotion, demotion, hiring, or firing of his subordinates?

3. Does the leader have the knowledge necessary to assign tasks to subordinates and instruct them in task completion?

4. Is it the leader's job to evaluate the performance of his subordinates?

5. Has the leader been given some official title of authority by the organization (e.g., foreman, department head, platoon leader)?

SITUATIONAL CONTROL SCALE

Enter the total scores for the Leader–Member Relations dimension, the Task Structure scale, and the Position Power scale in the spaces below. Add the three scores together and compare your total with the ranges given in the table below to determine your overall situational control.

1. Leader-Member Relations Total

2. Task Structure Total

3. Position Power Total

Grand Total

Total Score

Amount of Situational Control

| 51–70 | 31–50 | 10–30 |

| High Control | Moderate Control | Low Control |

Now you know your LPC score and your situational control score (based on your particular leadership situation, your team, group, department, or division). Do they match? That is, if you are high LPC, are your situational control scores in the 31–50 range; or if you are a low LPC, are they in either the 51–70 or the 10–30 range? If they match, you need not do anything. But if they do not match, Fiedler suggests making some changes. For example, if you want to increase your Leader–Member Relations you may make a special effort to communicate with your subordinates to decrease the level of conflict among them, and to be accessible to them. If you want to increase your task structure, you may make a special effort to develop procedures for doing the job. If you want to increase the power, you might ask for more power from your supervisor. Similarly there are things to do to decrease structure (design the task so that subordinates can decide how to do the job) and power (let subordinates make more of the important decisions). You can train subordinates, rotate them into other jobs, and so on. The point is to do things to change your environment so it will match your leadership style.

The emphasis on Fiedler's leadership theory is based on the fact that Fiedler, more than any other researcher, has tested his theory with a variety of methods, in a variety of realistic settings. For example, Fiedler and colleagues (1984, 1987) reported on a study of several mines, where a particular management training program based on his theory (Fiedler et al., 1977) was compared with a widely used program to develop supervisory skills that used organizational development approaches requiring consultant expenses from $80,000 to $150,000. The management training program, which was estimated to cost between $4,000 and $10,000 at most sites, was more effective than the other methods in improving both productivity and the mine's safety record.

While Fiedler's is by far the best-researched theory of leadership, there are a number of other theories that should be noted.