9.3. CONFLICT BETWEEN GROUPS

Conflict between groups is very common in organizations. In what follows, we will summarize some of the major findings in social psychology concerning the study of intergroup relationships (Worchel and Austin, 1985).

9.3.1. In-Groups, Out-Groups

The first point is that it is very easy to create confrontations between in-groups and out-groups. An in-group is one with which the individual is ready to cooperate and whose members consist of individuals who trust each other. An out-group consists of people one distrusts.

It is very easy to create in-group/out-group distinctions. For example, in a laboratory experiment, one can say to teenagers, "You belong to the yellow group," and the others constitute "the red group." With no other visible distinction, one says, "All right, you yellows, here is a pile of money. Divide the money between your group and the other group." This simple manipulation is sufficient to make the individuals who are doing the dividing favor their in-group. For instance, they may give 60 percent of the money to the in-group and 40 percent to the out-group. It is as if there were a natural way of thinking that "since I belong to this group and the other group is my 'enemy,' it is natural for me to give more to my group and to be a little distrustful of the other group." The research also shows that out-groups are perceived as more homogeneous than in-groups. In other words, the "other" people are "all the same." By contrast, in-groups are perceived as relatively heterogeneous. The members of one's in-group are perceived as "all different" from one another. These tendencies imply that we stereotype members of out-groups and may perceive them more inaccurately than we perceive the in-group.

It is useful to distinguish relationships that are intergroup from those that are interpersonal. In an interpersonal relationship, the individual is very much aware of who the other is. In the intergroup relationship, the individual is not aware of the other's personal characteristics. For example, when soldiers shoot at the enemy they do not care who that particular individual is. It is just a global reaction or judgment about the other person as a representative of a group. Intergroup relationships are more likely to develop than interpersonal relationships under the following five conditions: (1) when there is intense conflict, (2) when there is a history of conflicts, (3) when there is a strong attachment to the in-group, (4) when there is anonymity of membership in the out-group, and (5) when there is no possibility of moving from the in-group to the out-group.

Let us examine these conditions with an example from the relationship between researchers and marketing specialists. If the marketing specialists look at the world in a different way from the way the researchers do, then it is far more likely that the researchers will say that the marketing people are "all the same." On the other hand, if there is less conflict they may see differences between various members of the marketing group. Second, if there is a history of conflict between the two groups, then they are much more likely to look at each other in terms of their group rather than as individuals. Also, if the researchers feel very strongly about being researchers or the marketing types feel very strongly about being marketing types, they will perceive the people in the other group as undifferentiated. Anonymity means that you do not really know who the other people are. A marketing committee will make a decision and say "No!" or will send a letter to the research people that says, "We have decided not to support your proposal." There is no indication of who the people are that made the decision, and this increases the tendency to perceive them as all alike, as a group, and not as individuals. Finally, perception also tends to be intergroup when there is no possibility of moving from one group to another, as happens when the organizational structure is such that engineers and scientists never work in marketing or market department members do not work in research.

The interesting thing is that in-group favoritism occurs even when these five conditions do not operate! In other words, intergroup favoritism is such a common and fundamental idea (given that you are in my group I must favor you) that people are not critical of their own actions. In order to show favoritism, people do not need tension or conflict, a history of conflict, strong attachment to their group, anonymity of the out-group, or the inability to move to the other group.

The fact that the out-group is seen as a homogeneous entity means that stereotypes increase. Stereotypes are overdetermined because they occur for at least two reasons: (1) It is easier (requires less cognitive work) to see others as being more or less alike, and (2) it is so much simpler to deal with others as if they were alike. Studies have shown that people are more likely to generalize in the negative direction (toward criticism) from the behavior of one individual who is a member of an out-group to the whole out-group than to do so in the case of the in-group. In our example, our researchers are much more likely to stereotype and evaluate unfavorably the whole marketing department on the basis of the behavior of one of its members than they are likely to change their view of the research department on the basis of the behavior of one researcher.

9.3.2. Biased Information-Processing

This biased information processing focuses on ways how this type of an approach creates conflicts. The section on "Defects in Human Information Processing" in Chapter 2 further elaborates on this phenomenon. An interesting example of biased information processing is that people attribute positive actions by the in-group to internal aspects (e.g., they are honest), but positive actions by out-group members are considered due to external aspects (e.g., they were forced to act that way). In other words, suppose the marketing people unexpectedly did something very nice for the researchers. The researchers would claim that the marketing department members were forced to act in this way by outside circumstances. On the other hand, if they did something nasty, it would be explained as being "their nature"; that is, people make dispositional attributions (they were nasty people) when negative behavior of out-groups is perceived. Conversely, if the researchers (the in-group) did something nice, it would be explained as "their nature," but if they did something nasty, they would be perceived to have acted that way as a result of external circumstances.

9.3.3. Conflicts in Organization

Recent reviews of experimental work on conflict in organizations (DeDreu and Gelfand, 2008) suggest that there are many circumstances when moderate amounts of conflict may stimulate innovation and creativity. When a research team includes a member who looks at the research problem very differently from the way the other members do, even when that member is wrong, the difference of opinion can increase information search, and may uncover a solution that was not considered by any member of the research team. Therefore if, when the work begins, the best solution is not evident to any of the members of the research team, the team's work can benefit from dissent. Of course, dissent is not without costs. In dissent situations the decision will probably take longer, the research members may feel antipathy toward the member who has different views, and may emotionally block the implementation of the best solution. On the other hand, if the research team has the norm described in "Ethos of a Scientific Community" (Chapter 3), even if individuals are critical of the solutions proposed by others, the negative effects of dissent can be minimized. The complexities of the way dissent may be used to stimulate creativity are discussed in Schultz-Hardt, Mojzisch, and Vogelgesang (2008).

9.3.4. Coping with Conflict between Groups

What we said in the case of interpersonal conflict also applies to intergroup conflict: If superordinate goals (goals of both groups that neither group can reach without the help of the other) can be found, the relationship can be improved.

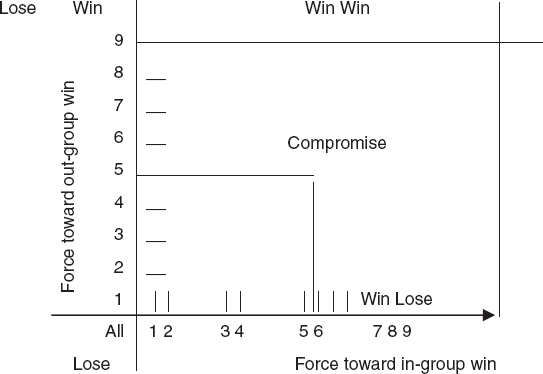

There are two orientations that one can adopt in an intergroup situation: One is called a win–lose orientation and the other is called a win–win orientation. In the win–lose orientation, one tries to win for one's in-group something that the out-group loses, while in the win–win orientation, one tries to win something for both groups. Another way to look at conflict is to examine the Conflict Resolution Grid of Blake and Mouton (1986, p. 76). The win–win orientation corresponds to position 9.9. The win–lose orientations are 1.9 and 9.1. Two other orientations—compromise and all lose, both less satisfactory than the win–win—are also shown in Figure 9.1.

For example, suppose the researchers have a design that satisfies many technical and production criteria, but which the marketing people find almost impossible to market. In a win–lose orientation either the technical people manage to impose the design or the marketing people manage to eliminate it from further consideration. In a win–win orientation a new design is developed that has the advantages visualized by the research group, but also incorporates the advantages of the ideal marketing design. Other positions shown in the diagram would be (a) the lose–lose position in which no design is adopted, and (b) the compromise position in which a design is adopted that has some, but not all, of the desirable elements of the designs of each of the groups in conflict. It is obvious that the win–win orientation is the most desirable. However, it should also be obvious that in order to reach that design one has to be very creative and come up with a very new concept. Such a concept may have either (a) none of the elements of the original design of the technical people, or (b) none of the elements of the original ideas of the marketing people. It is a fact that the win–win solution requires "insights" not available before the confrontation took place that leads to successful conflict resolution. So in this case we can talk about "productive" or "constructive" conflict, as opposed to talking about "destructive" conflict.

Figure 9.1. Intergroup Win–Lose Orientation

Research shows that the win–lose orientation is associated with cognitive distortions that make the outcome of the conflict undesirable for both sides. The "product" that is an outcome of this conflict (e.g., a negotiated agreement) is likely to be poor. In such cases the position of the in-group is perceived as very much more desirable than the position of the out-group. While the in-group knows its position well, it does not know or fully understand the position of the out-group. The position of the in-group appears to be much more desirable than it is. The "common ground" between the two positions is seen as belonging to the in-group's solution, and the in-group perceives only its own position as acceptable, using a "narrow cognitive field" to understand the positions of the various parties. In other words, in the win–lose orientation, the groups look at the conflict in a distorted, overly simple way.

In the case of a win–win orientation the product of the conflict (e.g., the negotiated agreement) often shows much creativity. It is more insightfully conceived and therefore more valuable. The in-group does not distort its view of the desirability of its own solution and understands much better the position of the out-group than is the case in the win–lose orientation. The full complexity of the issues is perceived. In other words, in the win–win orientation there is little distortion and the perception of the positions and values of the proposals of each party in the conflict is realistic.

When a win–win orientation is used, there is usually acceptance of the other side. There is trust, confidence, and communication between the two groups. Usually there are no threats, there is less cognitive distortion, and people do understand that there is common ground between their position and that of the other side. Also, they look for and are likely to adopt a creative orientation. In other words, they say, "Let's solve this problem together and let's solve it creatively. Let us find a solution that we have not thought about before, that will be satisfactory to both sides."

The distortions of information processing are particularly strong when there is no objective way to evaluate the information each side presents to the other. Distortions are minimized when the behavior of the other group is predictable. Predictability also has impact on the trust that each group feels toward the other. We trust people whose behavior we can anticipate.

One of the issues that comes up quite often when there is intergroup conflict concerns the question, who should go to a negotiation session? There is research showing that a satisfactory agreement is less likely to be reached when the negotiation session is attended by representatives of the group and not by the whole group. In other words, the representatives feel constrained by the fact that they are representing a group and thus have little flexibility to move. They freeze in a particular position and the two sides become deadlocked. On the other hand, when the whole group participates in the discussions there is usually some movement. If there is a choice, it is, therefore, much better to have a session in which both groups are present in the negotiations.

When a representative is given full power to represent the group and reach an agreement as he or she sees fit (in other words, when he or she does not need to go back to the group to convince its members that a particular decision is the best one obtainable), deadlock can be avoided. Such representatives speak for their group and also for themselves. When they see that there is a possibility of an agreement, they agree. It is a desirable (low-conflict) condition when the meeting becomes an interpersonal one involving two people, each representing a group honestly seeking to reach the best agreement that they, as individuals, can reach. The chances of creative solutions increase in such situations. The disadvantage of this solution, however, is that the group often feels the representative did not get a "good enough" agreement.

Certain conditions increase the probability that the intergroup conflict will become productive rather than destructive: (1) when there is a perception that cooperation is highly desirable; (2) when the out-group is seen as being heterogeneous rather than homogeneous (in other words, when we teach members of the in-group that there are people with different views in the out-group); (3) when the in-group and the out-group have common goals; (4) when there is mobility and some of the members of the in-group were members of the out-group in the past.

This is one of the rationales for job rotation in an R&D organization. By having people in the organization change their jobs and moving them from one department to another, they become able to deal with members of these other departments in conflict situations. Finally, it is helpful to have a condition in which the in-group is not using the conflict with the out-group as a means of consolidating the leadership position of the in-group's leader. In some situations the in-group is not sufficiently cohesive and its leader tries to create unity by leading the in-group into battle. This, however, is highly undesirable since it makes conflict difficult to resolve.

Conflict can become destructive when one or both sides see only a single issue as important. Usually when several issues are involved, it is possible for each side to concede on some issues, but when only one issue is critical, it is difficult for one or the other of the two sides to yield.

Blake and Mouton (1986) have described in detail their approach to conflict resolution. They utilized groups of 20–30 executives from industry who came together for two weeks to discuss interpersonal and intergroup relations. They were first exposed to controlled laboratory experiments, and then to the results of the experiments.

In Phase I, in-groups were formed and in-group cohesiveness was developed. Usually each in-group was concerned that another group might "do better," and these feelings were expressed kiddingly during coffee breaks. At that point, each group was provided with an identical human relations problem. The solutions were then compared by the researchers, who explicitly stated which solution was better and why, thus creating competition and a win–lose orientation. In some cases a group of outside judges was used or each group was invited to do the judging. When a group evaluated its own solution in relation to the others, it typically focused on the differences between the solutions and the good points of its own solution, ignoring the strengths of the other group's solution.

Blake and Mouton discuss the barriers to cooperation that arise from the win–lose orientation. Of special interest to R&D managers who may be in conflict with accountants, finance experts, or marketing specialists is that these and other (e.g., Davis and Triandis, 1971) studies show that one can resolve conflict better when the entire groups meet together rather than when each group elects a representative to negotiate with the other side. In short, have all the people in your department who are affected meet with all the accountants or the marketing people who are relevant.

Conflict is usually resolved better when the solution is arrived at by the two parties in conflict than when the solution is imposed by outsiders. It is very helpful to identify distortions in perception, which occur when one's perspectives become narrow, as usually happens when one is tense, or when one thinks the in-group products are much more desirable and of higher quality than they really are, or if the common ground between the solutions of the two sides seems to be part of the in-group's solution exclusively. This job can often be helped by having a third party listen to the positions of the two sides.

Superordinate goals have been found to be helpful in reducing conflict. As already mentioned, such goals are common goals that one side cannot reach without the help of the other. Experiments, field studies, and consultant experiences suggest that such goals are highly desirable. Managers will do well to search for and foster such goals for groups that might be in conflict.