EIGHT

From Strategic Business Unit Marketing to Corporate Marketing

Marketing is strategy.

IN GENERAL, THE LITERATURE on marketing strategy focuses on business units and ignores the role of marketing at the corporate level. This has probably reinforced the traditional belief that all marketing is local—a belief that has resulted in the placement of the marketing function in SBUs or in country organizations, rather than at headquarters. Relatively few companies have a chief marketing officer (CMO) alongside a chief financial officer (CFO) or a chief operating officer (COO) to influence the CEO and corporate strategy.

While most of the marketing functions and almost all marketing activities in an organization have historically fallen to the divisional and country organization levels, more firms are enhancing the role of marketing at the corporate level. The CMO position is emerging in companies as diverse as Coca-Cola, Nokia, KPN Qwest, Pizza Hut, and Reuters. However, many CEOs and companies still hesitate to appoint CMOs or build a large corporate marketing function because they do not know whether marketing can add any significant value from the corporate center. The more diversified the individual businesses, the more decentralized the organization; the larger the number of brands in the portfolio, the more challenging to conceptualize the benefits of corporate marketing.

The Role of the Corporate Center

If marketing is to break out of the shackles of the conventional business unit boundaries and play an important role at the corporate strategy level, then corporate marketing must help the CEO address the following three questions about corporate strategy:1

- Portfolio choices: What business should we be in? Companies generally choose their portfolio of businesses by arraying individual business units on matrices such as the Boston Consulting Group matrix or General Electric matrix. Regardless of the two-dimensional portfolio model, one dimension reflects market attractiveness while the other indicates the company’s competitive strength.

Companies differ on how they use such matrices. Some diversified companies seek a “balanced” portfolio of cash cows, rising stars, question marks, and so on. Others have specific rules, like General Electric’s condition that each business be first or second in market share; otherwise, the manager must “fix it, close it, or sell it!”

- Portfolio relationships: What value should our businesses add to each other? Which relationships among the businesses actually create synergies that benefit an individual unit as part of the whole?

Disney searches for synergies within its portfolio of movies, music, theme parks, merchandising, videos, software, retail, and television business. Companies constantly seek economies of scale by sharing operating resources such as procurement, manufacturing, and advertising.

- Parenting skills: What value does the corporate center add? The so-called parenting advantage is when the parent company adds such value to its portfolio businesses that any individual business unit is worth more as part of this particular parent than as part of another parent or as a freestanding unit. Parenting advantage exists if the parent has unique capabilities, resources, skills, expertise, or access to important stakeholders that can help the individual business units.2

For example, in the heavily regulated Indian market between 1960 and 1990, when operations required a license from the government, highly diversified conglomerates emerged due to the parenting advantage of access to key bureaucrats. After market deregulation, these conglomerates divested many business units to concentrate on a few core activities.

Corporate marketing can help the CEO address these three corporate strategy challenges. Regarding the appropriate portfolio and portfolio interactions, a strong corporate marketing team brings fresh insights by using a marketing lens to examine the strategic coherence of portfolio choices while searching for synergies between the business units. The outcome of this analysis should be a number of top- and bottom-line initiatives that corporate marketers lead to leverage the corporate portfolio. Regarding the parenting advantage, corporate marketing can champion the development of market-based capabilities that make the individual business units more customer-focused.

The Search for Marketing Synergies

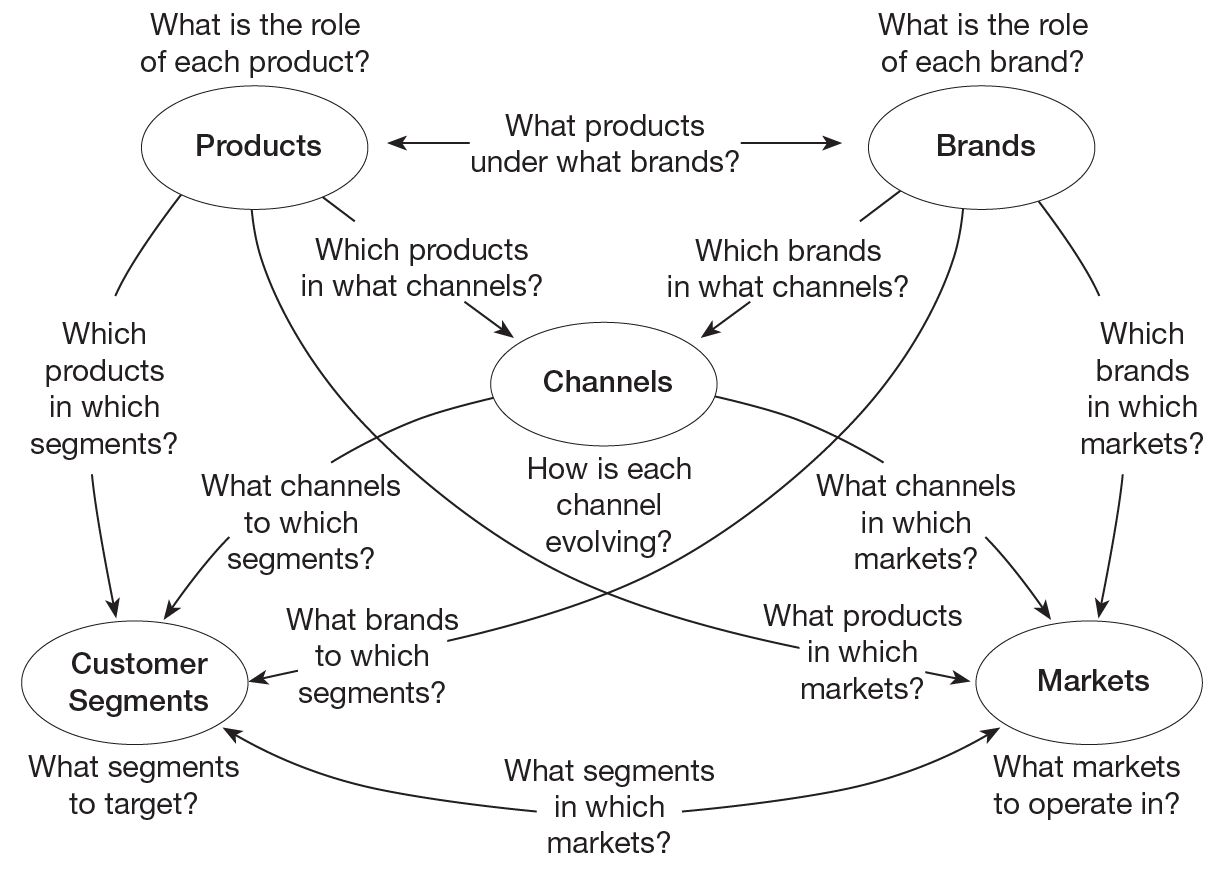

Underlying the portfolio of business units in a global corporation are many complex implicit and explicit marketing choices (see figure 8-1). Each business unit decides what products to sell, under which brand names, targeting which customer segments and markets, and through what channels of distribution. In any large company, the potential number of possible combinations of these five dimensions can overwhelm managers. For example, having 8 product lines, 4 customer segments, 10 brands, 5 distribution channels, and operating in 100 markets or countries leads to 160,000 decision points!

The Complex Corporate Marketing Logic

Given the complexity of the problem, each business unit must make these decisions for itself and optimize its own logic without fully considering the impact on the other units. Individual business units and country managers may not see opportunities to leverage other units or may struggle for cooperation. Corporate marketing can add value here by reexamining the company’s portfolio of products, brands, channels, customer segments, and markets, and asking questions (per figure 8-1) from the global corporate perspective, not from an individual one.

Consider Sara Lee, a conglomerate with 160 core brands, thousands of product lines, and some 200-odd operating companies, each with its own profit center. No one shared even packaging systems because, as CEO Steven McMillan observed, “the decentralized culture was so ingrained they thought a sister company would overcharge them.”3

In its search for synergies, corporate marketing must ensure that the company does not sacrifice variety for efficiency. Marketers must balance the desire for cost savings through economies of scale and the potential for increased penetration of customer segments and markets through economies of scope and managed variety.

By adopting the corporate perspective, corporate marketers can view the products, brands, channels, customers, and markets as potential platforms to exploit across individual business units. Corporate marketing can lead the push from the “vertical think” about individual countries and product divisions to “horizontal thinking” around customer needs and segments. Table 8-1 outlines some of the potential sources of marketing synergies, distinguishing primarily top-line initiatives from predominantly bottom-line ones. Corporate marketers should look for synergies from both.

Leverage Product Platforms

Could the firm leverage the products of some business units in the distribution channels, brands, or markets of other business units? For example, Wal-Mart’s entry into China familiarized it with potential product suppliers there, and enabled it to set up a Chinese global sourcing center. Products sourced for and tested in the Chinese stores have now migrated to stores outside China: Chinese suppliers now provide approximately $12 billion worth of products annually for Wal-Mart. If, by more efficient sourcing from China, Wal-Mart can reduce its worldwide costs of goods sold (COGS) by half a percent, that’s more than any profits that it could generate in China over the next ten years.

Leveraging the Corporate Portfolio

How can a company create the product variety necessary to penetrate multiple segments while keeping product development and manufacturing costs from spiraling? By working off a few standard platforms with strictly defined interfaces, companies such as Toyota, Dell, Sony, and Volkswagen can achieve variety without the deleterious effects on economies of scale. The Toyota Camry, Lexus ES300, Sienna minivan, Toyota Highlander, and the Lexus RX300 SUVs have shared many interchangeable parts and a common platform across generations. The RX300, in particular, demonstrates the success of platform sharing. By sharing platforms, Toyota has used a well-tested, stable, engineered car platform as a starting point for what ultimately ends up as a rather “truck-like” vehicle. The RX300 has a truck or SUV-like appearance and utility while maintaining car-like attributes such as ride comfort and smooth handling.

How can a firm develop and launch products simultaneously across countries rather than introduce them through sequential country-by-country rollout? Setting up cross-national product concept and market launch teams prevents the reinvention of new products for each country, thereby reducing product development costs and increasing speed to breakeven volume.

Exploit Brand Platforms

Would some brands in the corporation add value to other business units? What brand extensions can the company launch? Can it merge brands in different product categories for greater impact and efficiency? Has the company allocated resources across brands most effectively? Can the corporate brand add value by endorsing business unit brands? Chapter 6 on brand rationalization should help corporate marketers answer these questions.

Corporate marketing is also the steward of the corporate brand. It develops, refines, and protects the common brand heritage and strengthens brand equity. At Electrolux, corporate marketing develops standard brand planning processes and templates for all marketing organizations and trains marketers on brand and marketing communications standards. In addition, Electrolux as an endorser brand bestowed the values of international expertise and global technical competence upon the local brands. Corporate marketing sets the guidelines on how individual brands and business units can leverage the corporate brand.

Extend Channel Platforms

Could other business units leverage the strong distribution channel of a particular business unit? Would the company increase its distribution clout by approaching the channels as a company rather than as individual business units? For example, Ford Motors’s luxury brands of Volvo, Land Rover, and Jaguar could combine their distribution points and consolidate into larger dealerships rather than individual dealers for each brand.

Chapter 4 on channel migration should help corporate marketers answer questions about moving customers to lower-cost channels and penetrating faster-growing channels. Corporate marketing can help to develop the necessary competence to effectively manage multichannel marketing across business units.

Nurture Customers as Platforms

Could we increase our share of a customer’s wallet by cross-selling products or innovating solutions for certain customer segments? Could we add products to the corporation’s portfolio? Citibank merged with Travelers to cross-sell banking services, credit cards, and insurance to each customer. Amazon is adding categories rapidly to leverage its customer base of 25 million. By seeking synergy and leverage, corporate marketing can create complex product-service bundles to exploit customer relationships.

Bottom-line initiatives usually involve developing the competence to understand the lifetime value of, and the cost of serving, each customer. Based on this analysis, one can prune unprofitable customers from the portfolio, especially if cross-selling and solution-selling initiatives to such customers fail. Many banks, credit card companies, and telecommunications firms are currently discouraging customers who will never yield a profit.

Develop Markets as Platforms

Corporate marketing can initiate regional consolidation of marketing staff to exploit economies of scale and scope. Instead of segmenting markets at the country level, companies are developing segments on a pan-European basis. For example, across eleven European Union countries, four cross-national segments for yogurts exist to varying degrees in each country.4 One of these segments, health and innovation, comprised approximately 26 percent of yogurt consumers in Denmark, Germany, and Great Britain, 18 percent in Ireland and Netherlands, about 7.5 percent in Belgium and Greece, and 3 to 5 percent in France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. As a result, the appropriate yogurts and brand positioning can be developed for each of the four segments rather than for each individual country, which results in faster product development cycles and shared advertising platforms.

Can we transfer the knowledge of markets of one business unit to another business unit not in those markets? For example, B&Q, the do-it-yourself retailer, traditionally operated on one floor with merchandise stacked to the ceiling. In China, relatively shorter customers would not reach up for merchandise and often called for assistance in what was intended to be a self-service format. As a result, B&Q China designed and installed a two-story store, which it imported into B&Q’s home market, the United Kingdom, to cope with soaring property prices and tough planning restrictions. The importance of emerging markets as a growth engine for companies merits a closer look.

Emerging Markets as a Growth Platform

Companies can get too comfortable with existing customers and countries and limit growth initiatives to wringing more sales from those segments. Too often, companies and their competitors go to the same well, overlooking underserved opportunities. In order to expand their customer base, companies increasingly will have to consider the mass markets of emerging economies.

Target Growing Masses in Emerging Markets

Companies in the developed world face a fundamental challenge. The slow birth rate in North America, Japan, and Western Europe has resulted in an older population with limited, if any, overall population growth. In particular, in Europe the ratio of actively working people to pensioners will drop from 4 to 1 to 2 to 1 within the next two decades. Certain industries such as health care, elderly homes, and leisure will grow, but others will struggle.

Companies tend to have ambitious growth targets. Aspirations to grow 10 to 15 percent per annum are common, even when the overall industry is growing by 3 to 5 percent. If we combined the five-year projections of the top five or six players within an industry, it would appear as if industry sales were expected to double. Since a firm cannot increase prices forever or sell more shampoo to receding hairlines, it cannot meet these growth projections in the developed markets. Yes, product innovation helps, but sustained product innovation is rare in mature markets with mature products.

To generate growth, companies must focus intently on the emerging markets of Asia, Latin America, and Africa.5 For example, Ford estimates that the automotive market in developed countries will grow at 1 percent per annum and 7 percent in emerging economies.6 In 2002, passenger car sales in China rose 55 percent over 2001. In the U.S. and European passenger vehicle markets, cheap financing is fueling price wars to stabilize volume.

The almost 2.5 billion people in the emerging markets of China, India, and Indonesia account for more than 40 percent of the world’s population. No wonder Coca-Cola invested $2 billion in these three countries during the 1990s. Over the past five years, Danone, Heinz, and Unilever have spent more than a billion dollars acquiring local companies in Indonesia to position themselves favorably with the mass population there.

Some companies from the developed world trip on the doorstep of emerging markets. In the mid-1980s, Honda led the worldwide market for motor scooters with its superior technology, outstanding quality, and brand appeal.7 After successfully entering Thailand and Malaysia, Honda turned to India, once again peddling its existing models through outlets in big cities rather than listening to potential customers, most of whom lived in rural India and expected low costs, durability, and reliability. Honda withdrew from India in three years.

The business models of most companies from developed countries force them to target a very small segment of the developing market population—at most, the top 20 percent of the income pyramid. Major multinational corporations are missing opportunities to innovate solutions for the 4 billion of the 6 billion people on this planet who make less than $2,000 per annum.8

Keep the Value Proposition Simple, and Keep It Cheap

The typical value proposition of multinational companies in the emerging markets is usually a global product with slight modifications. Thanks to cheap local labor and other input costs, companies can usually offer products made in emerging markets at somewhat lower prices than those in developed markets, though not low enough for mass consumption.

The value networks in which multinationals operate cannot yet deliver value propositions that suit the masses of the developing world. Billions of people with unmet needs—the millions of HIV-AIDS sufferers in Africa, the billions without clean drinking water, electricity, housing, education, or adequate medicines—could be a source of growth and profits for those firms willing to experiment with as-yet-unimagined ways to create customer value.

We need innovative market concepts and business models that target the overlooked bottom 80 percent through attractive and profitable value propositions. The overriding principles in reaching emerging market masses are simplicity and affordability. Keep it simple and keep it cheap. In India, to target villages with a population of 5,000 or less, Max New York Life’s typical term policy has a payout of $208 and an annual premium of $2. In Africa, London’s Freeplay Energy Group has designed a wind-up radio, charged by cranking a handle, which allows its African customers without electricity or expensive batteries to get vital health and agricultural information. Word has it that a few of these radios surfaced in the United States in 2003 during North America’s worst blackout in history.

To realize the poor as an opportunity requires thinking differently about the value proposition. To lower costs and increase the market, companies are shifting from ownership and individual users to low-cost access and communities of users, especially involving high-fixed-cost products infrequently used. If nobody in a village can afford a telephone or personal computer, then maybe the entire village could, by paying per use as Grameen Telecom has demonstrated in Bangladesh.

Reinvent the Three Vs Model for the Masses

Simple and inexpensive value propositions are only possible by reinventing the value networks that underlie the current industry business models at much lower costs. Consider the business model of multinational pharmaceutical firms: It factors in high research and development expenses, massive marketing budgets, and prohibitive prices for patent-protected drugs. How could it possibly work to reach the billions who really need those products? Fortunately, companies have successfully reinvented the industry three Vs to serve the poor profitably.

Grameen Bank in Bangladesh pioneered the microcredit industry that dispenses loans averaging $15 to people who lack collateral, a service that would never be profitable for multinational banks given their cost structure. By removing the need for collateral and creating a banking system based on mutual trust, accountability, participation, and creativity, Grameen Bank has grown to serve 2.3 million borrowers, 98 percent of whom are women with very low default rates. As many as 9,000 microlenders now serve the developing world; some in Bolivia, Mexico, Kyrgyzstan, and Uganda are becoming big and profitable enough to tap into private capital and evolve into banks.9

Banco Azteca has similarly targeted a large underserved market in Mexico, the 16 million households that earn between $250 and $1,300 per month—factory workers, taxi drivers, teachers—whose accounts are too small (too uneconomical) for the large established banks.10 The bank’s sister company, Grupo Elektra, is Mexico’s largest appliance retailer and has fifty years experience in providing consumer credit to this segment. With a repayment rate of 97 percent, this firm knows the segment and its financial means better than anyone else. Converting the credit departments of its extensive store network into bank branches made perfect strategic sense.

With the motto “a bank that’s friendly and treats you well,” Azteca welcomes customers that other banks shun. Realizing that most of its customers lack proof of income or proper identification, it invested $20 million in high-tech fingerprint readers. No need for any documentation. The database includes consumer’s credit histories and names of neighbors who can help track down delinquent debtors. Credit becomes a matter of community pride.

Nothing inherent, except perhaps their mind-set, prevents multinational companies from serving the poor in emerging markets through three Vs innovation. In fact, they probably have more resources and potential capabilities. For example, Unilever’s Indian subsidiary, Hindustan Lever, is one of the best at reaching the masses in developing countries.

Hindustan Lever: An Emerging Market Winner

Hindustan Lever is constantly searching for growth initiatives that can effectively serve the billion-person Indian mass market. Realizing that most Indian consumers were too poor to buy a full-size bottle of shampoo or detergent, besides having no space to store it, Hindustan Lever pioneered the individual-use sachets which sell for about 2 cents each. They are enormously popular.

Initially, Hindustan Lever set up a distribution system that reached only 100,000 of the 638,000 villages in the country. To access the largely untapped rural market, where 70 percent of the population lives, the company initiated Project Shakti ( “strength” ).11

Under Project Shakti, Hindustan Lever trains women in small villages, usually with a population under 2,000, in business skills so that the women can launch small owner-operated businesses. Since the women have little education and no experience in running an independent business, they receive follow-up training, essential to success. Many of these women are offered, and choose, to become rural sellers or distributors of Hindustan Lever products, creating a low-risk, sustainable microenterprise for themselves. By selling Hindustan Lever products in their neighboring four or five villages, they can generate a steady income of approximately 1,000 rupees (around $20) per month, almost doubling their previous household income.

Hindustan Lever has achieved these breakthroughs by developing a cadre of managers who understand the bottom-of-the-pyramid consumer. Each executive recruit must spend eight weeks in the villages of India on a community project to empathize with these consumers. Imagine if every multinational company, pushed by corporate marketing, developed a pool of emerging market experts who really understood the poor as a business opportunity rather than as a problem.

Transfer Best Practices Across Markets

Hindustan Lever has exported some of its successes with low-price, low-cost products, such as iodized salt and Wheel, a laundry detergent. When Unilever launched the detergent brand “Ala” in Brazil, Indian managers provided product development knowledge, low-cost manufacturing solutions, and low-cost advertising techniques such as wall paintings and rural display counters.12 Ala has become a runaway success in Brazil.

An emerging market mind-set requires one to monitor positive spillover effects when marketing in developed countries. For example, an average NBA basketball game draws a television audience of 1.1 million households. On November 20, 2002, a Houston Rockets game featuring the new Chinese star, Yao Ming, against one of the league’s worst teams, the Cleveland Cavaliers, drew 5.5 million live viewers in China and another 11.5 million for the evening replay.13 That makes Yao Ming more influential than any other basketball player since Michael Jordan. With global media, everyday marketing decisions in the developed countries can influence prospects in emerging markets. Here again, corporate marketing can foster greater horizontal thinking.

Building Customer-Focused Capabilities

Despite public declarations, few companies are truly customer-focused. If you are fielding more customer complaints, seeing declining marketing productivity, or watching new products die on the vine, then your company probably needs to become more customer-focused. Corporate marketing can help build crucial capabilities that increase customer focus throughout the organization.

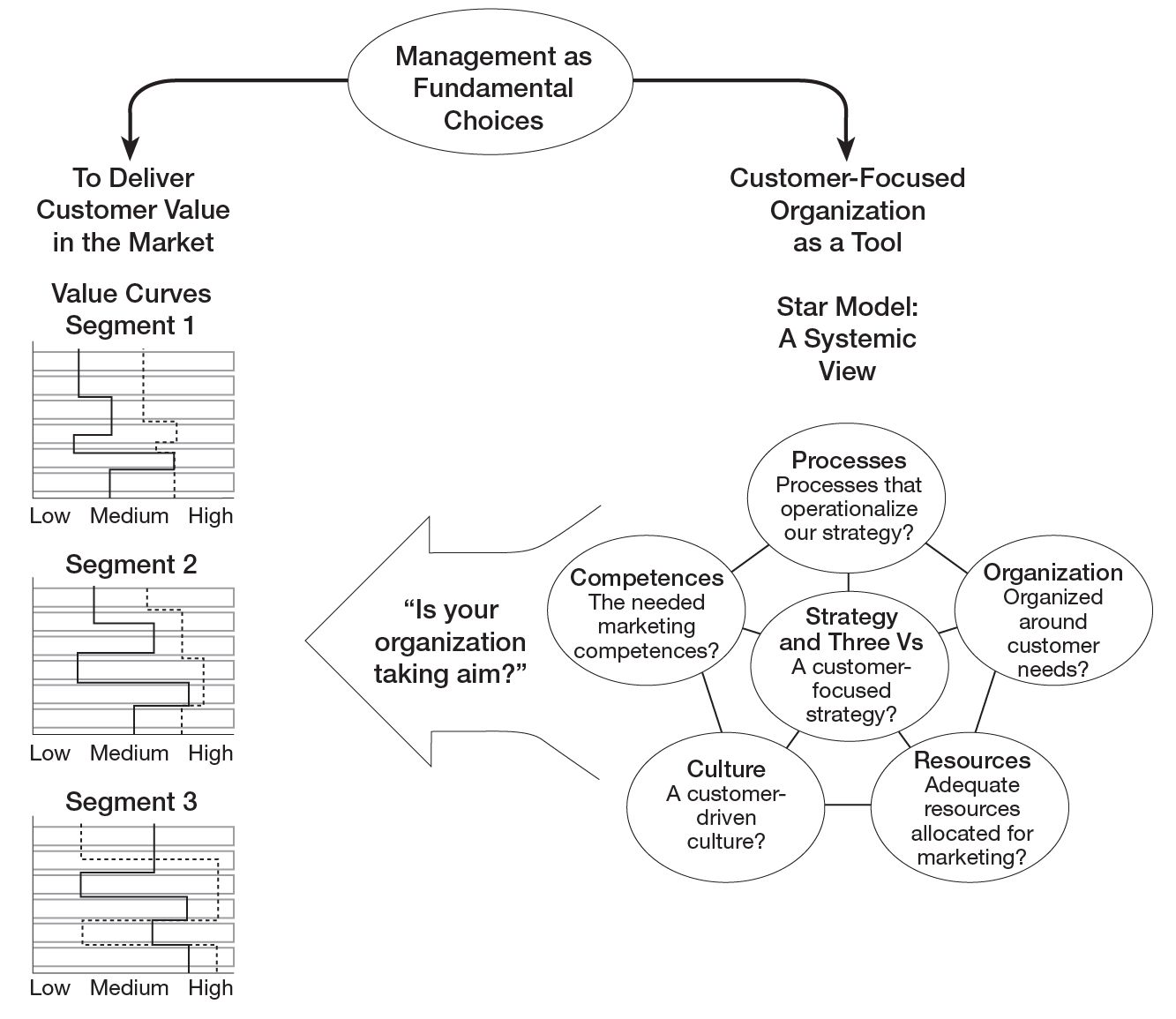

Responding totally to customers requires both educating the organization on customer-focused behavior and developing a methodology for assessing responsiveness. In organizations, what gets measured, gets done. Figure 8-2 presents a six-step approach to developing and measuring the customer-focused organization using value curves and the star model.14

What does “customer-focused” really mean? Does it refer to a mind-set, a culture, activities, or an organization? It refers to all of these. A customer-focused organization has a customer orientation (strategy and culture), a customer-driven configuration (organization and processes), and customer investments (competences and resources).

Customer-Focused Strategy Map

Corporate marketing defines the customer-focused firm as one that, above all, delivers demonstrated customer value in each of its business segments. No one can build a customer-focused organization without clear definitions of the valued customers and the value proposition to deliver. A strong customer culture without a well-articulated strategy is as useful as a car without a steering wheel.

The Customer-Focused Organization

Source: The author acknowledges the contributions of Andy Boynton to this figure.

A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words. This oft-heard saying also applies when demonstrating a customer-driven strategy. Drawing a value curve to show how the firm’s value proposition differs from the competition’s for a target segment (discussed in chapter 2) is the most effective way to depict how the organization creates value for its customers. In figure 8-2, the relevant attributes for the customer appear on the vertical axis of the value curve. The lines exhibit the performance of the focal firm (solid lines) on each attribute versus the competition (dashed lines).

Once everyone understands the value curves, corporate marketing can more easily mobilize the organization to deliver this value to customers. A number of companies have used the star model and figure 8-2 to recognize the levers of customer-focused organizational capabilities.

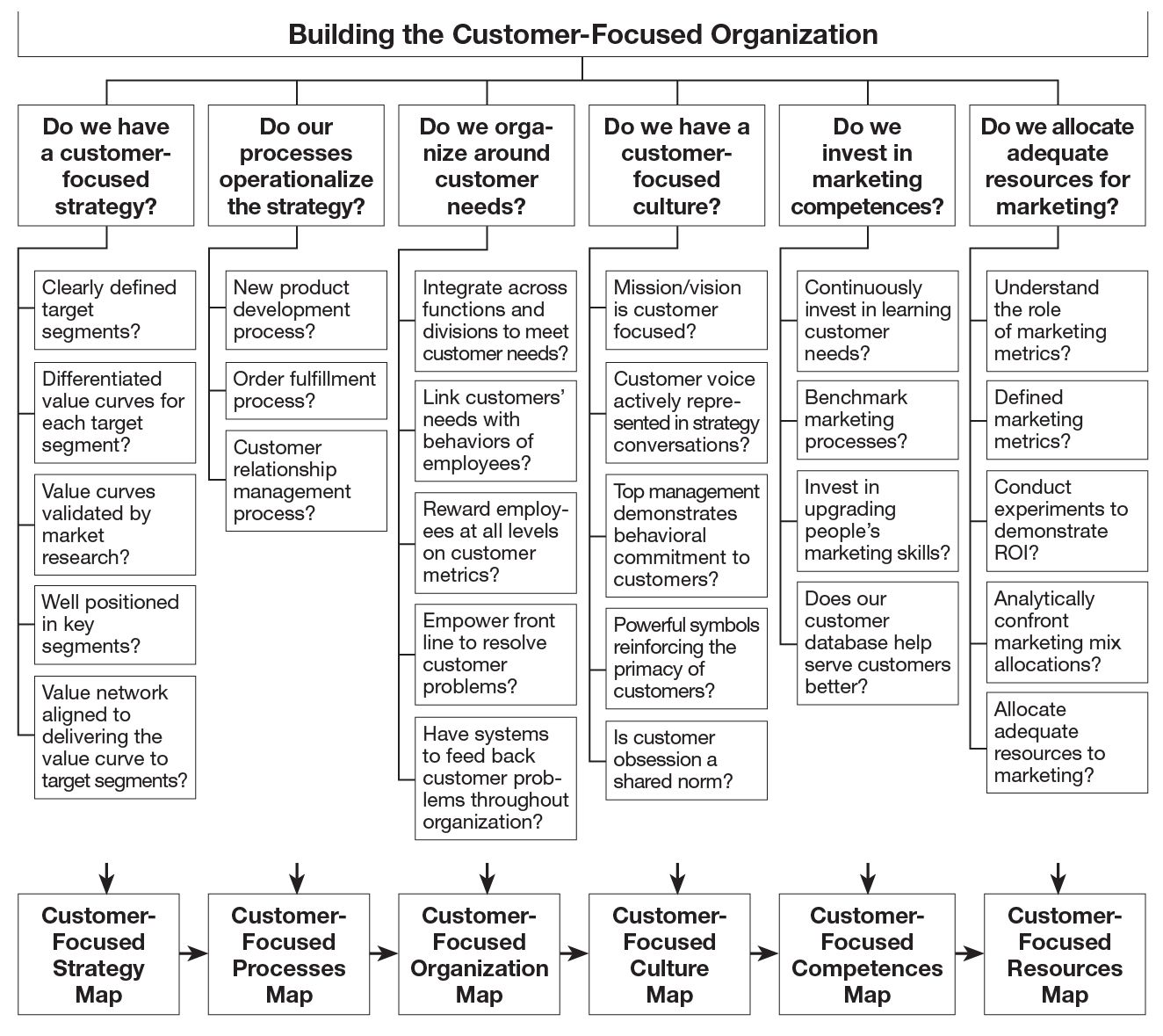

Strategy Is Asking the Right Questions. Drawing value curves for each segment can help answer the following questions: (1) Have we clearly defined target segments? (2) Do we have differentiated value curves for each target segment? (3) Have we validated the value curves through market research? (4) Have we positioned ourselves in key segments? (5) Have we aligned our value network to deliver our value propositions to the target segments? Building a customer-focused organization requires efforts across multiple dimensions. For a poster version of the questions to ask in order to assess the degree to which an organization is customer focused, see figure 8-3.

Building the Customer-Focused Organization

Customer-Focused Processes Map

Ultimately, customers get a bundle of processes, usually the new product development process, the order fulfillment process, and the customer relationship management process. Managers must align the apparently contradictory logic of these three main processes to deliver the value curves to the valued customers.

New Product Development Process. The new product development process is a creative activity and may attract employees who eschew financial or customer discipline. The challenge is to strike a balance between the freedom to create and the commitment to deliver customer value. Tight constraints will hinder creativity, and loose ones will result in expensive new products that suffer from “feature creep” (features that nobody wants). For example, Gillette’s razor strategy (build a better product and consumers will trade up) did not work for its Duracell batteries because consumers did not want better batteries, just cheaper ones.

Encouraging R&D personnel to spend time with customers, rotating them through marketing and sales, focuses the product development process on the differentiation articulated by the value curves. A Sony engineer may, for example, spend six months selling stereos on the pavement before ever participating in product design.

Order Fulfillment Process. The goal of the order fulfillment process is to reduce costs through economies of scale. To lower costs, operations typically prefer long production runs and low variety. One industrial company had a fill rate of about 50 percent on distributors’ orders, resulting in lost sales, a frustrated sales force, and dissatisfied customers. Investigators found that the factory managers were compensated on plant-level profits, and so the plant always processed the few large long-run standard orders promptly and pushed the short-run orders further out in the production schedule. Clearly, the company had not aligned its order fulfillment process with its strategy. The plant should have processed the orders of more “valued” customers and more urgent orders rather run the process exclusively on cost considerations.

Customer Relationship Management Process. The customer relationship management process focuses on acquiring and retaining customers. Companies typically look for flexibility and economies of scope in this process. A disciplined approach here requires seeking meaningful flexibility by aligning customer acquisition and retention to the value curves that help pinpoint where one should be flexible and for which customers.

By understanding the three Vs, sales can concentrate on the valued customers instead of scattering efforts across all customers. For example, in the customer retention process, an online grocer differentiates among customer A, B, and C based on their value to the firm. If an item, say tomatoes, fails to arrive, then all customers who complain receive immediate credit, but B customers get the tomatoes free with their next order, and A customers get the tomatoes free immediately.

Firms typically assess each of the above three processes on quality, speed, and efficiency. However, the customer-focused firm also assesses how customer-friendly the process is, whether it prioritizes customers according to their value to the firm, and how well it delivers the defined value curve.

Customer-Focused Organization Map

Companies all too frequently make it difficult for the customer to do business with them because of how they are organized. For example, a residential customer wishing to purchase a fixed land line, an ISDN line, and a mobile phone from British Telecom would have to call three different departments. A customer-focused company continuously strives to bring its organizational logic close to the customer’s logic so that it is effortless for the customer to interact with the firm.

Organize Around Customers. Whereas the processes above typically require cross-functional coordination to satisfy customers, most companies still operate in functional silos. Corporate marketing can push to integrate functions and divisions by identifying where internal cross-functional cooperation is critical for customer satisfaction. For example, the supply chain and sales people must coordinate closely to meet promised delivery dates. Marketing and R&D must collaborate to produce a greater number of “hit” new products. Operations and marketing must partner internally to improve the global market launch process.

After defining the functional interfaces, corporate marketing can set up forums for interaction between marketing and the other functions. It should push to establish (1) the rules of engagement among marketers and other internal and external partners, and (2) performance expectations that encourage cooperation with these partners. Ideally, companies should organize around market segments and treat them as individual profit centers, as Capital One does. This arrangement increases the capability to sense and respond to customer opportunities faster.

Specify, Measure, and Reward Customer-Oriented Behaviors. Corporate marketing must articulate the customer-focused financial measurements. While most companies attempt to reward customer-oriented behaviors, successful companies differ in level of detail, extent of participation, and weight placed on such rewards.

For the organization to produce customer-defined quality, it must translate the attributes of the value curves into precise behaviors for the front line and then reinforce these behaviors through rewards. For example, MBNA, the credit card company, has established goals of thirty-minute credit increase approval, twenty-one-second or second-ring telephone pick up, twenty-four-hour replacement of lost or stolen cards, and fourteen-day new account application processing. Each day that the staff exceeds these goals, the company contributes to the employee bonus pool. No wonder MBNA meets or exceeds 98 percent of its goals daily.15

Siebel ties 50 percent of management incentive compensation and 25 percent of salesperson compensation to measures of customer satisfaction. Unlike most companies that pay it immediately, Siebel pays the incentive a year after the sales contract is signed, when it can accurately determine customer satisfaction with results.16

Harrah’s, the casino operator, has a bonus plan that rewards workers with extra cash for improved customer satisfaction scores at the property. In 2002, the employees at one property, despite having record-breaking financial results, received no bonus because their customer satisfaction score was mediocre.17 What a powerful message to send the entire organization.

Empower Employees to Resolve Customer Problems. Corporate marketing must empower employees to resolve customer problems and complaints. This freedom improves the speed and often the efficiency of complaint resolution. Marketers should also develop a feedback loop to communicate customer problems throughout the organization as Microsoft does for Windows.

Customer-Focused Culture Map

Building a customer-focused culture takes time. However, the culture that permeates the organization is perhaps the most important differentiator of customer-focused firms. A customer-driven culture starts at the top of the organization.

Create a Customer-Driven Mission. Has the company stated its mission in terms of what the organization does for customers? For example, Wal-Mart’s “lowering the cost of living for the world” is better than “being the best in our industry.” Customer-driven companies infuse their strategy conversations with the customer voice through market research, time spent with important customers, and internal conflict resolution based on customer needs and expectations. At some companies, the annual strategy meetings begin with a presentation by an important customer.

Involve General Managers with Customers. Nothing is more powerful than CEOs regularly calling on customers. Corporate marketing can cultivate a customer-driven culture by creating opportunities for senior managers to grapple with customer-related issues and by challenging senior general managers to devote time to marketing and engaging customers. At MBNA, executives devote four hours a month to answering or listening to customer calls.18 Corporate marketing can also appoint general managers to serve on marketing oversight or award boards, as the Electrolux Group Brand Award does, not just to improve quality but to recognize superior or innovative employee efforts toward customers.

Manipulate Symbols to Reinforce the Primacy of Customers. Symbols can be powerful in fostering shared beliefs about the primacy of customers. At MBNA, the pay envelopes of employees remind them that customers are the source of their salaries. At the department store Nordstrom, employees leave the parking spaces closest to the store entrance for customers’ cars.

Develop Norms of Customer Obsession. Whereas a company needs formal rules and procedures for standardizing performance in ordinary situations, standardization does not usually result in outstanding customer service or quality. Why? Because outstanding customer service depends on how a company deals with extraordinary situations that are impossible to anticipate, unique to a particular person, and difficult to solve.19 Companies need a shared norm of customer obsession, one that emphasizes how the organization exists for, and goes out of its way to help, the customer. Such strong norms increase clarity about priorities and expectations. The CEO and CMO must vocalize, live, and reinforce these norms daily. Jan Carlson, former CEO of SAS, noted, “Our moment of truth is when our customer meets our frontline. A bad moment can depreciate our assets. We have 100 million moments of truth each year at SAS.”20

Customer-Focused Competences Map

Corporate marketing must take primary responsibility for enhancing the marketing competence of the organization through four different actions: continuously learning about customers; benchmarking marketing; developing marketing talent; and investing in customer-focused systems.

Continuously Learn About Customers. Marketing departments should invest continuously in learning about customer needs and testing managerial instincts against consumer reality. Too often, consumer research turns into a sterile presentation by an external market research firm delivered through mind-numbing PowerPoint slides. Corporate marketing can develop processes and tools to gather, understand, use, and share consumer insights. At IDEO, the California-based design firm that designed the Apple mouse and the Palm handheld computer, designers personally visit experts and consumers at points of consumption and then share their insights through photographs hung on company walls.

Benchmark Marketing. Benchmarking can improve the quality of marketing processes. Internal benchmarking across divisions and countries can facilitate the identification of marketing best practices and record practical lessons to improve organizational marketing effectiveness. Some firms build and manage marketing councils to connect their various marketing organizations. To push innovative ideas not performed anywhere in the company, corporate marketing can: (1) identify sources of best practices outside the organization, (2) develop and share external and internal best practice process maps, and (3) create a network that encourages competition for results and resources among the different marketing units within the company.

Develop Marketing Talent. Corporate marketing leads the development of marketing talent across the organization. This requires a whole host of initiatives, including establishing appropriate recruiting, reward, recognition, and retention systems. Defined career paths for marketing experts that rotate marketers across the organization can be effective in building informal communities across divisions to facilitate transfer of ideas.

Procter & Gamble has developed excellent training programs that create a cadre of marketing experts.21 Procter & Gamble’s marketing training program has incubated many CEOs, such as Jeffrey Immelt of General Electric, Steve Ballmer of Microsoft, Paul Charron of Liz Claiborne, Stephen Case of AOL, Margaret Whitman of eBay, and Scott Cook of Intuit. Each year, about a thousand marketing recruits attend a week-long boot camp, and more than twenty marketing electives are available for more experienced employees. Procter & Gamble has designated 20 employees to serve as deans and 265 employees to serve as teachers. All of its 3,400 marketers around the world receive the same training.

Too often, companies pay lip service to developing customer competence in their employees. As a rule, the CEO should participate in some marketing training each year to set an example for investing in learning. At Harrah’s, all employees must undertake a curriculum based on factors that motivate loyalty among Harrah’s best customers. Since employees earn much of their compensation through tips, they receive their tipped wages while in training.22

Invest in Customer-Focused Systems. Over the past two decades, companies have invested considerably in technology. Yet many of these investments have not enabled companies to focus more on customers. The CMO and corporate marketing can discuss technology investments in terms of their effect on customer acquisition, satisfaction, and retention. Does the technology create common organizational databases to capture knowledge? Do the information systems allow employees to share customer data freely across the organization? Do the integrated customer databases create complex views of the customer? Do IT processes enable employees to use databases in key marketing activities such as corporate branding and customer relationship management?

Customer-Focused Resources Map

To receive organizational resources, marketers must demonstrate tangible financial outcomes. Bottom-line marketing involves five steps: understand the role of marketing metrics; define marketing metrics; conduct marketing experiments; confront marketing mix allocations; and allocate adequate resources for marketing.

Understand the Role of Marketing Metrics. When linking marketing to shareholder value and financial performance, one can easily forget to balance indicators of past financial performance (financial metrics) and indicators of potential financial health (marketing metrics). Andy Taylor, chairman and CEO of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, observes, “I went through a period of healthy paranoia in the early 1990s. We were a billion dollar company, growing fast; profitability was good.... Background noise . . . suggested our customer service had started to slip. The Enterprise service quality index [ESQI] was a breakthrough for us. Over the years, we have refined it until now we ask customers only two questions: Are you satisfied with our service? Would you come back?”23

Completely satisfied customers are three times more likely to return to Enterprise. Each of the 5,000 branches of Enterprise receives regular feedback on ESQI, and no one gets promoted from branches with below-average ESQI scores, no matter how impressive their financial performance. Rising ESQI scores reassure Taylor more than Enterprise’s strong cash flow or increased market share. He explains, “ESQI doesn’t mean we can ignore other [factors] but it will keep us on track.”24

Define Marketing Metrics. Corporate marketing can influence the definition of the relevant marketing metrics at each of the five levels of business and ensure that each division and country tracks, collects, and reports the appropriate metrics using a common methodology so that executives can compare data across the firm (see table 8-2). Managers can slice and dice comparable data in various ways to diagnose the overall performance of the corporation and demonstrate the productivity, or lack thereof, of marketing expenditures. At Grand Vision, the European optical chain, corporate meetings devote a day to discussing marketing metrics after participants present the financial numbers and employee statistics.

Conduct Marketing Experiments to Demonstrate Return on Investment. Corporate marketing must demonstrate the links between marketing spending, customer satisfaction/retention data, and financial outcomes, such as revenues and profits. By tracking this data over time, the organization can differentiate between marketing investments like brand building and marketing expenditures such as promotions.

Marketing Metrics

Marketing experiments help the company identify which types of marketing expenditures yield results. For example, to assess the efficacy of sales training, Motorola-Canada selected eighty-four employees with similar sales productivity and trained half of them.25 The newly trained group increased sales by 17 percent in the first three months after training, whereas the control group’s new order volume dropped by 13 percent. Motorola estimates that every dollar spent on training yields $30 over three years.

A company such as Anheuser Busch (AB) constantly experiments to examine effective practices in marketing and advertising. Once it finds a program that works, its discipline and persistence in implementation sets AB apart from competitors. Galeries Lafayette, the French department store chain, calls these two stages experimentation (identifying the most profitable actions) and industrialization (prioritizing and applying the best formulas). Experimenting with its 1.5 million cardholders, the firm has isolated several actions that increase turnover through cross-selling and one-to-one marketing, and has reduced costs by optimizing mass mailings and new channels such as e-mail and short messaging service (SMS).

Confront Marketing Mix Allocations. Kraft has developed a method that ranks brands by returns on investment for each marketing mix element. For example, it compares the return on investment on advertising across brands and then reallocates advertising dollars from low ROI brands to high ROI brands. By doing so, and repeating the exercise for each of the remaining elements of the marketing mix, Kraft can optimize its marketing expenditures.26

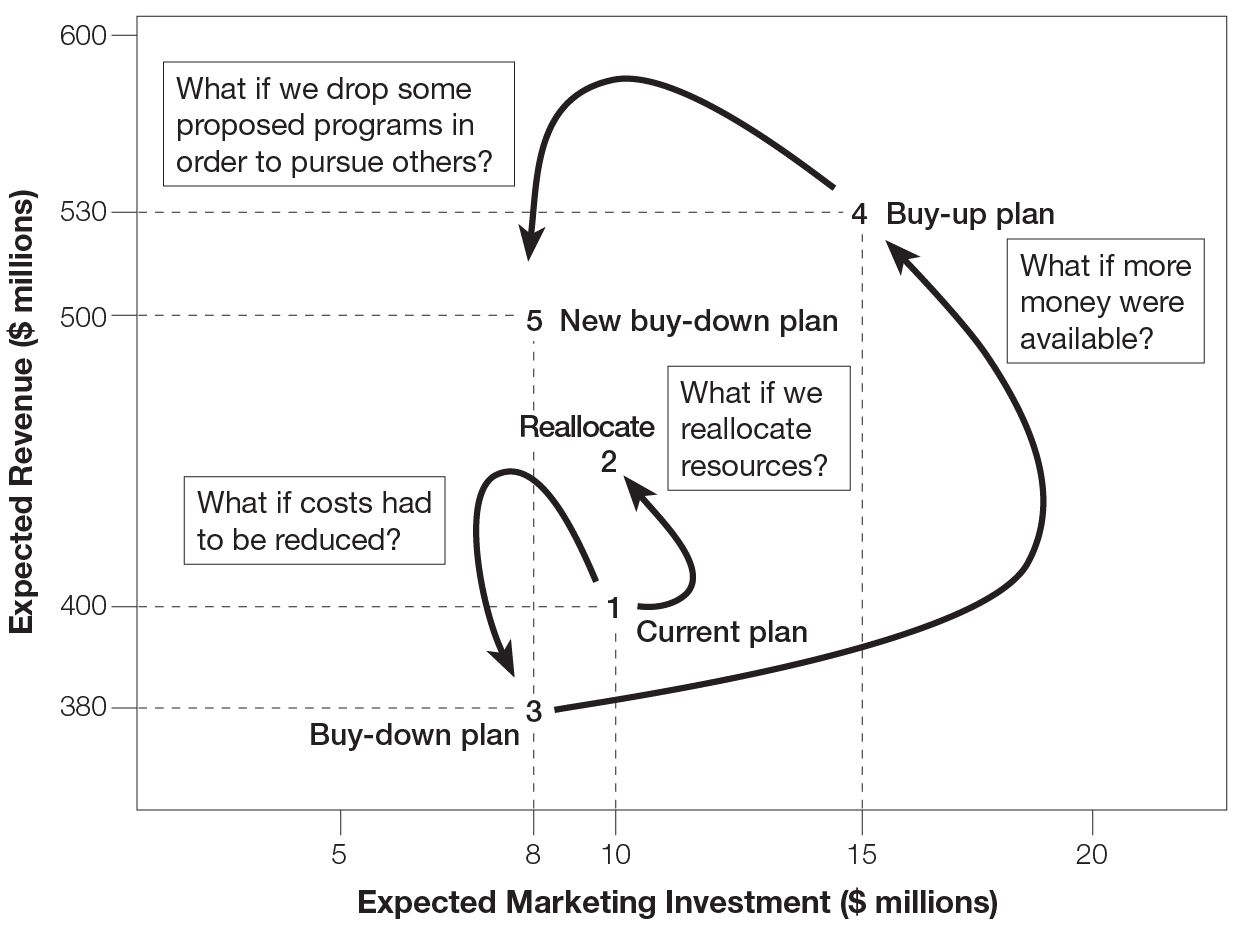

Anyone who wants to reallocate major marketing resources should develop and present buy-down, buy-up, and reallocate alternatives (see figure 8-4). Corporate marketing should champion such an analytical approach, forcing the organization to confront questions such as, what would happen if we transferred a portion of the customer acquisition budget to customer retention? For example, a creative CMO of a tour operator once took half the marketing budget for the year and devoted it to satisfying customers on their holidays and found substantial positive impact on the next year’s bookings.

Marketing Allocation Alternatives

Source: Adapted from Paul Sharpe and Tom Keelin, “How SmithKline Beecham Makes Better Resource-Allocation Decisions,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1998): 92–105.

One consumer packaged goods company realized that it was spending $12 annually per U.S. household on mostly mass media advertising with only a scattered shotgun effect. Its research indicated that about 12 million of the 120 million U.S. households accounted for 80 percent of the company’s profits, of which 6 million accounted for 50 percent of the profits. Why not reduce the advertising expenditure by $1 per household annually and redirect the savings of $120 million into developing a database of the 6 to 12 million heavy-use households? It could then target these important households with more personalized direct marketing techniques.

Allocate Adequate Resources to Marketing. Functions and divisions often lobby for the largest possible share of human, financial, and systems resources in any organization. A savvy CEO or CMO can ask important questions to redefine the debates in customer terms: Have you dedicated enough resources to customer acquisition and retention? Will you spend them in the most optimal manner? What benefits will the customer obtain from these expenditures?

The Challenge of Being a Customer-Focused Firm

One should not mistake a customer-focused organization with a powerful corporate marketing function and bloated marketing departments. Some academics and marketers still determine the degree of an organization’s customer focus by asking whether executives value, respect, and view marketing as a benefit to the firm relative to other departments.

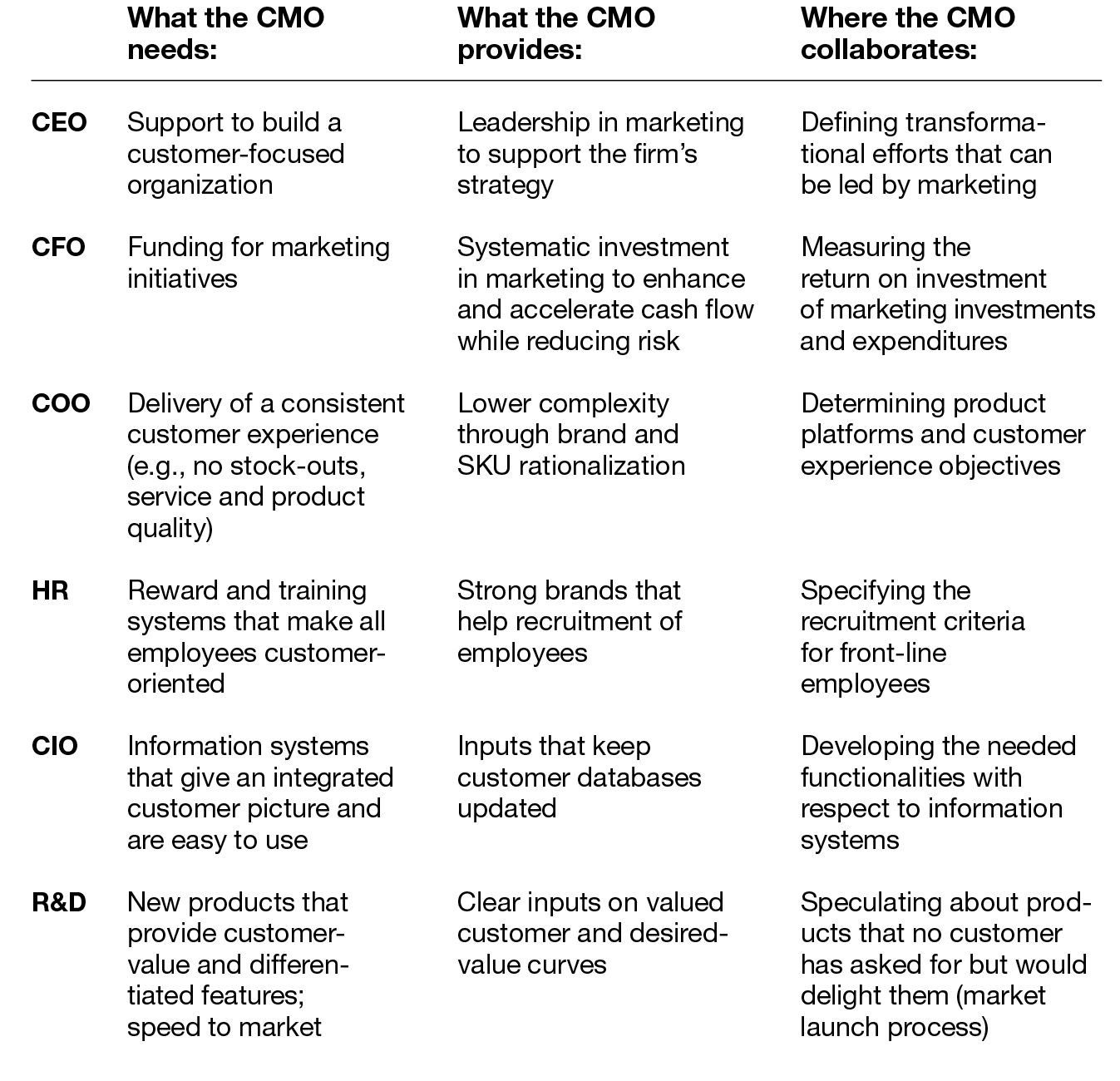

A powerful marketing group at the corporate level does not necessarily result in a better, more customer-focused organization. Caring about and organizing around customers and overriding company-think with customer-think in designing a firm’s operations must transcend any particular function. To promote such an organizational mind-set requires corporate marketing to define what it needs from all the other functions, what it will contribute, and where collaboration is necessary, as shown in table 8-3. A company can never be too customer driven because as soon as it gets close, the customer moves. Targeted segments change, customers’ needs evolve, and new competitors, channels, and technologies materialize, all of which necessitate a new customer-driven strategy.

Marketing and Its Functional Interfaces

Source: Inspired by “Stewarding the Brand for Profitable Growth,” Corporate Executive Board, Washington, DC, 2001.

Making Market Transformations Happen

Naturally, we can expect corporate marketing to champion those marketing initiatives that potentially benefit multiple business units or require coordination among them, especially if such initiatives are innovative, long-term, costly, high-risk, or transformational in nature. The seven marketing transformations enumerated in this book all share these attributes. However, given the substantial nature of these initiatives and the potential organizational resistance, marketers need the CEO on board in order to thrive.

Change, even for the better, usually traumatizes organizations. It forces people to think and act differently. More important, the seven major transformations of the CEO’s marketing manifesto will likely spark significant shifts in the relative power of individuals and divisions within the organization. Individuals typically adopt four postures to change depending upon how it affects them (positive or negative) and their profile (active or passive).27

Given human nature, those for whom the change has a negative impact will either actively resist or undermine it (resisters) or adopt a passive wait-and-see attitude (traditionalists). Managers must empower the change agents—those for whom the potential impact of change is positive and who have the energy to lead it—while energizing the bystanders who see the potential good but dither over taking an active role. The question is, should the CEO be the primary change agent for market transformations?

The CEO as Commander, Chairman, Coach, and Catalyst

Instinctively, the CEO may assume ownership of the seven transformations that comprise his marketing manifesto. The CEO as leader lends the change program credibility and high priority. However, top executives should counsel the CEO against directing every transformation initiative. The typical demands on the CEO, especially of a public company, may consume the time and the energy needed to tackle the matter, and the CEO may lack expertise in the subject.

Professor Paul Strebel has mapped the degrees of urgency and resistance in four different transformation processes (see table 8-4). Intriguingly, each change process requires the CEO to assume a specific role in that process. There are two caveats: (1) Since the urgency and resistance to change will differ across companies, managers cannot state categorically that an individual transformation, such as brand rationalization, should follow a particular change process; and (2) major organizational transformations are messy. Typically, one must apply a different process at each stage of the initiative, as more of an evolution, not a revolution.

Transforming Processes

| Strong Resistance | Task Force Change | Top-Down Turnaround | ||||

| CEO Role: | Chairman | CEO Role: | Commander | |||

| (Intensive solicitation of opinions) | (Take it or leave it) | |||||

| Process: | Process: | |||||

| • | Ask change agents to staff task forces | • | Ask change agents to cascade down | |||

| • | Ensure task forces solicit bystanders’ opinions | • | Unequivocal message to bystanders | |||

| • | Confront resisters with choice of buying in | • | Force resisters out by making buy-in immediate | |||

| • | Put traditionalists in implementation roles | • | Rapid reorganization for traditionalists | |||

| Widespread Participation | Bottom-Up Initiatives | |||||

| CEO Role: | Coach | CEO Role: | Catalyst | |||

| (Collaborator) | (Provocative) | |||||

| Process: | Process: | |||||

| • | Ask change agents to facilitate participation | • | Challenge change agents to take initiative | |||

| • | Initiate widespread collaboration with bystanders | • | Encourage bystanders to imitate | |||

| • | Throw performance challenges to resisters | |||||

| • | Crowd out resisters with growing support | |||||

| • | Integrate traditionalists into entrepreneurial teams | |||||

| Weak Resistance | • | Involve traditionalists in network of linked teams | ||||

| Low Urgency for Change, Unclear Direction | High Urgency for Change, Clear Direction | |||||

Source: Adapted from Paul Strebel, The Change Pact: Building Commitment to Ongoing Change (London: FT Prentice Hall, 1998).

Chapter 3 presents the transformation from selling products to innovating solutions at IBM. At the start of the transformation, IBM was losing money and under pressure to divest some of it its divisions; there was great urgency for change. When the incoming CEO, Lou Gerstner, decided to remake IBM into a solution-seller, he faced stiff internal resistance from IBM product and country heads, who had historically enjoyed complete independence. Providing solutions forced them to kowtow to those who actually coordinated and delivered customer solutions and to cooperate in the customer’s best interest. Lou Gerstner had to adopt the classic top-down turnaround process with him as commander-in-chief.

The move to global distribution partnerships in FMCG companies described in chapter 5 is usually more gradual. Since retailers are still integrating their own international operations for worldwide purchasing, the urgency for change is less dramatic. Given that global account management would diminish the dominion of country managers, firms must often adopt the task force approach to overcome resistance. Amid this transformation process, some FMCG companies are confronting recalcitrant managers individually and calling on the CEO to coordinate work groups and synthesize dissimilar points of view, so as to keep everyone moving forward.

When resistance is weak or isolated, frontline managers can drive change or use widespread participation methods. Top management cannot readily know who in the organization has valuable market-driving ideas. In chapter 7, NEC and Sony demonstrated that open competitions can surface these ideas and their proponents, while the CEO plays coach and sponsor of the market-driving process.

Finally, as chapter 4 notes, the emergence of the Internet enabled many firms to sell directly to smaller customers. During the dot-com boom, companies rushed impetuously to enter this channel of distribution. At one computer manufacturer, there was little internal resistance to direct online sales, but nobody really knew how to approach this channel. Therefore, in a bottom-up process with CEO as catalyst, executives freed division heads to approach online selling in whichever manner best suited their individual division. Knowing that several divisions wanted to explore the new channel, the CEO challenged them to do so. After one division’s modest success, the CEO encouraged other divisions that could potentially benefit from the channel to imitate it.

Regardless of which change process a company adopts and which corresponding role the CEO plays, transformational marketing initiatives absolutely need top management support in order to succeed. Since the initiatives developed in this book traverse different functions and country organizations, they will undoubtedly encounter turf battles that pervade large companies. The CEO is usually the peacemaker in such subversive situations.

Stimulate Great Conversations Around Customers

Besides their role in the transformation process, CEOs should be customer champions at the board level, by stimulating great conversations around customers’ needs and behavior. To spare marketing from the daily tactical matters, CEOs should ask the broad questions about how their company creates value for customers; what role their brand plays in their customers’ lives now and in the future; and what role advertising will play in the next decade. CEOs should challenge top corporate management to create the time and space for such conversations about customers—and maybe even institute rules, as Lou Gerstner, the former CEO of IBM did, against using overheads and PowerPoint presentations .28

CEOs must be role models for rigor and rationality by contrasting widely held assumptions about the customer against the results of marketing experiments. As Socrates observed, we approach wisdom only through rigorous questioning to level false arguments. Rather than making a rash decision, Alfred Sloan of General Motors once suggested to his board: “I propose we give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain some understanding of what the decision is all about.” CEOs must institutionalize the questioning of assumptions about consumers, channel members, employees, and their respective actions and aspirations. Without such conversations, a company is unlikely to form a shared understanding of the company’s mission, strategy, and values.

Leadership is about doing the right thing when nobody is watching. We have witnessed too many CEOs and corporate leaders follow the path of Thrasymachus, a skillful Greek sophist who argued that wise men do as they like without being caught. Rather, they’d do better to follow Plato’s argument that, as repositories of collective behaviors, leaders must exercise self-discipline and lead for the broader good. Consumer trust is in the long-term interest of companies and society. The mission of a truly customer-focused firm should be to improve customers’ lives, and its values should encompass customer welfare. Only then can customer capitalism rule.

Marketing as a Change Agent

There has probably been no better time than now for the rise of marketing. Today, marketing is in a perfect position to galvanize the organization, as value creation strategies shift from the financial engineering of the past decade to old-fashioned customer value creation.

The challenges to marketing are many, but each unearths new opportunities for seizing organizational leadership. Given increasing price pressures, marketing must spearhead the firm’s move from selling products to providing solutions. As distribution channels consolidate, marketers must jump-start the transition to global account management structures. Despite industry commoditization, marketing must adopt a brand rationalization program to concentrate on and differentiate the company’s core brands. As channels proliferate, marketing must swiftly exploit new channels of distribution to generate growth. Marketers must resist sterile consumer and market research that results in incremental innovation and instead drive market concept innovation to deliver unimagined consumer experiences.

Marketing must prove that it is willing and ready for its leadership role in transforming the company. It must convince others of its unique capabilities, resources and skills, and its mind-set to lead—and that it has matured as a discipline to become more strategic, cross-functional, and bottom-line oriented.