Chapter 3. A Simple Maven Project

Introduction

In this chapter, we introduce a simple project created from scratch using the Maven Archetype plugin. This elementary application provides us with the opportunity to discuss some core Maven concepts while you follow along with the development of the project.

Before you can start using Maven for complex, multimodule builds, we have to start with the basics. If you’ve used Maven before, you’ll notice that it does a good job of taking care of the details. Your builds tend to “just work,” and you only really need to dive into the details of Maven when you want to customize the default behavior or write a custom plugin. However, when you do need to dive into the details, a thorough understanding of the core concepts is essential. This chapter aims to introduce you to the simplest possible Maven project and then presents some of the core concepts that make Maven a solid build platform. After reading it, you’ll have an fundamental understanding of the build lifecycle, Maven repositories, dependency management, and the Project Object Model (POM).

Downloading This Chapter’s Example

This chapter develops a very simple example that will be used to explore core concepts of Maven. If you follow the steps as described, you shouldn’t need to download the examples to recreate the code produced by Maven. We will be using the Maven Archetype plugin to create this simple project, and in this chapter we won’t modify the project in any way. If you would prefer to read this chapter with the final example source code, the example project may be downloaded with the book’s example code at http://www.sonatype.com/book/mvn-examples-1.0.zip or http://www.sonatype.com/book/mvn-examples-1.0.tar.gz. Unzip this archive in any directory, and then go to the ch03/ directory. There you will see a directory named simple/, which contains the source code for this chapter. If you wish to follow along with the example code in a web browser, go to http://www.sonatype.com/book/examples-1.0 and click on the ch03/ directory.

Creating a Simple Project

To start a new Maven project, use the Maven Archetype plugin from the command line:

$ mvn archetype:create -DgroupId=org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03

-DartifactId=simple

-DpackageName=org.sonatype.mavenbook

[INFO] Scanning for projects...

[INFO] Searching repository for plugin with prefix: 'archetype'.

[INFO] artifact org.apache.maven.plugins:maven-archetype-plugin: checking for

updates from central

[INFO] -----------------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] Building Maven Default Project

[INFO] task-segment: [archetype:create] (aggregator-style)

[INFO] --------------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] [archetype:create]

[INFO] artifact org.apache.maven.archetypes:maven-archetype-quickstart:

checking for updates from central

[INFO] Parameter: groupId, Value: org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03

[INFO] Parameter: packageName, Value: org.sonatype.mavenbook

[INFO] Parameter: basedir, Value: /Users/tobrien/svnw/sonatype/examples

[INFO] Parameter: package, Value: org.sonatype.mavenbook

[INFO] Parameter: version, Value: 1.0-SNAPSHOT

[INFO] Parameter: artifactId, Value: simple

[INFO] * End of debug info from resources from generated POM *

[INFO] Archetype created in dir: /Users/tobrien/svnw/sonatype/examples/simple

mvn is the Maven 2 command.

archetype:create is called a Maven goal. If you

are familiar with Apache Ant, a Maven goal is analogous to

an Ant target; both describe a unit of work to be completed in a

build. The -Dname=value pairs are arguments that

are passed to the goal and take the form of -D

properties, similar to the system property options you might pass to

the Java Virtual Machine via the command line. The purpose of the

archetype:create goal is to quickly create a

project from an archetype. In this context, an archetype is defined as “an original model or type

after which other similar things are patterned; a prototype.”[2] A number of archetypes are available in Maven for

anything from a simple Swing application to a complex web application.

In this chapter, we are going to use the most basic archetype to

create a simple skeleton starter project. The plugin is the prefix

archetype, and the goal is create.

Once we’ve generated a project, take a look at the directory structure Maven created under the simple directory:

simple/simple/pom.xml

/src/ /src/main/

/main/java /src/test/

/test/java

This generated directory adheres to the Maven Standard Directory Layout. We’ll get into more details later in this chapter, but for now, let’s just try to understand these few basic directories:

The Maven Archetype plugin creates a directory that matches the

artifactId. Simple. This is known as the project’s base directory.

Every Maven project has what is known as a Project Object Model (POM) in a file named pom.xml. This file describes the project, configures plugins, and declares dependencies.

Our project’s source code and resources are placed under src/main. In the case of our simple Java project, this will consist of a few Java classes and some properties files. In another project, this could be the document root of a web application or configuration files for an application server. In a Java project, Java classes are placed in src/main/java, and classpath resources are placed in src/main/resources.

Our project’s test cases are located in src/test. Under this directory, Java classes such as JUnit or TestNG tests are placed in src/test/java, and classpath resources for tests are located in src/test/resources.

The Maven Archetype plugin generated a single class

org.sonatype.mavenbook.App, which is a 13-line

Java class with a static main function that prints out a

message:

package org.sonatype.mavenbook;

/**

* Hello world!

*

*/

public class App

{

public static void main( String[] args )

{

System.out.println( "Hello World!" );

}

}

The simplest Maven archetype generates the simplest possible program: a program that prints “Hello World!” to standard output.

Building a Simple Project

Once you have created the project with the Maven Archetype plugin by following the directions from the previous section (Creating a Simple Project”) you will want to build and package the application. To do so, run mvn install from the directory that contains the pom.xml:

$ mvn install [INFO] Scanning for projects... [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------- [INFO] Building simple [INFO] task-segment: [install] [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------- [INFO] [resources:resources] [INFO] Using default encoding to copy filtered resources. [INFO] [compiler:compile] [INFO] Compiling 1 source file to /simple/target/classes [INFO] [resources:testResources] [INFO] Using default encoding to copy filtered resources. [INFO] [compiler:testCompile] [INFO] Compiling 1 source file to /simple/target/test-classes [INFO] [surefire:test] [INFO] Surefire report directory: /simple/target/surefire-reports ------------------------------------------------------- T E S T S ------------------------------------------------------- Running org.sonatype.mavenbook.AppTest Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.105 sec Results : Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0 [INFO] [jar:jar] [INFO] Building jar: /simple/target/simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar [INFO] [install:install] [INFO] Installing /simple/target/simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar to ~/.m2/repository/org/sonatype/mavenbook/ch03/simple/1.0-SNAPSHOT/ simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar

You’ve just created, compiled, tested, packaged, and installed the simplest possible Maven project. To prove to yourself that this program works, run it from the command line:

$ java -cp target/simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar org.sonatype.mavenbook.App Hello World!

Simple Project Object Model

When Maven executes, it looks to the Project Object Model

for information about the project. The

POM answers such questions as: What type of project

is this? What is the project’s name? Are there any build

customizations for this project? Example 3-1 shows the default pom.xml file created by the Maven Archetype

plugin’s create goal.

<project xmlns="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0

http://maven.apache.org/maven-v4_0_0.xsd">

<modelVersion>4.0.0</modelVersion>

<groupId>org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03</groupId>

<artifactId>simple</artifactId>

<packaging>jar</packaging>

<version>1.0-SNAPSHOT</version>

<name>simple</name>

<url>http://maven.apache.org</url>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>junit</groupId>

<artifactId>junit</artifactId>

<version>3.8.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</project>This pom.xml file is the

most basic POM you will ever deal with for a Maven

project. Usually a POM file is considerably more

complex, defining multiple dependencies and customizing plugin

behavior. The first few elements—groupId,

artifactId, packaging,

version—are known as the Maven coordinates, which uniquely identify

a project. name and url are

descriptive elements of the POM, providing a

human-readable name and associating the project with a project web

site. Lastly, the dependencies

element defines a single, test-scoped dependency on a unit testing

framework called JUnit. These topics will be further introduced in the

next section, Core Concepts,” and in Chapter 9. All you need to know at this point is

that the pom.xml is the file that

makes Maven go.

Maven always executes against an effective POM, a combination of settings from this project’s pom.xml, all parent POMs, a Super POM defined within Maven, user-defined settings, and active profiles. All projects ultimately extend the Super POM, which defines a set of sensible default configuration settings and which is fully explained in Chapter 9. Although your project might have a relatively minimal pom.xml, the contents of your project’s POM are interpolated with the contents of all parent POMs, user settings, and any active profiles. To see this “effective” POM, run the following command in the simple project’s base directory:

$ mvn help:effective-pom

When you run this, you should see a much larger POM that exposes the default settings of Maven. This goal can come in handy if you are trying to debug a build and want to see how all of the current project’s ancestor POMs are contributing to the effective POM. For more information about the Maven Help plugin, see Using the Maven Help Plugin” in Chapter 2.

Core Concepts

Now that we’ve just run Maven for the first time, this is a good point to introduce a few of the core concepts of Maven. In Example 3-1, you generated a project that consisted of a POM and some code assembled in the Maven Standard Directory Layout. You then executed Maven with a lifecycle phase as an argument that prompted Maven to execute a series of Maven plugin goals. Lastly, you installed a Maven artifact into your local repository. Wait—what is a “lifecycle”? What is a “local repository”? The following section defines some of Maven’s central concepts.

Maven Plugins and Goals

In the previous section, we ran Maven with two different types

of command-line arguments. The first command was a

single plugin goal, the create goal of the

Archetype plugin. The second execution of Maven was a lifecycle

phase, install. To execute a single Maven plugin goal, we used the

syntax mvn archetype:create,

where archetype is the identifier of a plugin and

create is the identifier of a goal. When Maven

executes a plugin goal, it prints out the plugin identifier and goal

identifier to standard output:

$ mvn archetype:create -DgroupId=org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03

-DartifactId=simple

-DpackageName=org.sonatype.mavenbook

...

[INFO] [archetype:create]

[INFO] artifact org.apache.maven.archetypes:maven-archetype-quickstart:

checking for updates from central

...

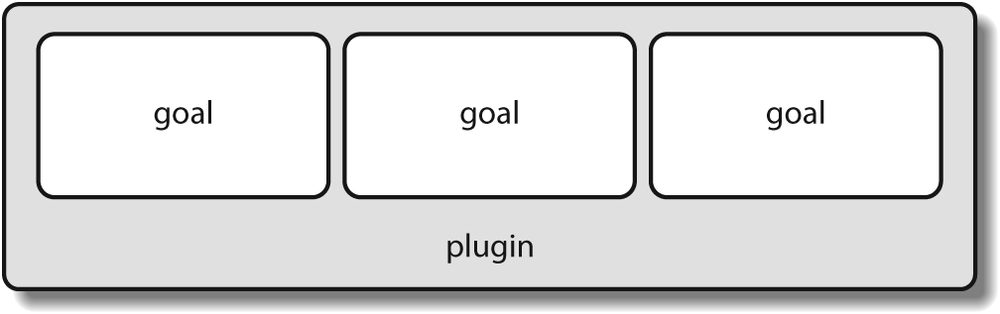

A Maven plugin is a collection of one or more goals (see Figure 3-1). Examples of Maven plugins can be simple core plugins such as the Jar plugin that contains goals for creating JAR files, the Compiler plugin that contains goals for compiling source code and unit tests, or the Surefire plugin that contains goals for executing unit tests and generating reports. Other, more specialized Maven plugins include the Hibernate3 plugin, for integration with the popular persistence library Hibernate, and the JRuby plugin, which allows you to execute Ruby as part of a Maven build or to write Maven plugins in Ruby. Maven also provides you with the ability to define custom plugins. A custom plugin can be written in any number of languages, including Java, Ant, Groovy, BeanShell, and, as previously mentioned, Ruby.

A goal is a specific task that may be executed as a

standalone goal or along with other goals as part of a larger

build. A goal is a “unit of work” in Maven. Examples of goals

include the compile goal in the Compiler plugin,

which compiles all of the source code for a project, or the

test goal of the Surefire plugin, which can

execute unit tests. Goals are configured via configuration

properties that can be used to customize behavior. For example, the

compile goal of the Compiler plugin defines a set

of configuration parameters

that allow you to specify the target JDK version or whether to use

the compiler optimizations. In

the previous example, we passed in the configuration parameters groupId

and artifactId to the create

goal of the Archetype plugin via the command-line parameters

-DgroupId=org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03 and

-DartifactId=simple. We also passed the

packageName parameter to the create goal as

org.sonatype.mavenbook. If we had omitted the

packageName parameter, the package name would

have defaulted to

org.sonatype.mavenbook.ch03.

Note

When referring to a plugin goal, we frequently use the

shorthand notation: pluginId:goalId.

For example, when referring to the create goal in the Archetype plugin,

we write archetype:create.

Goals define parameters that can define sensible default

values. In the

archetype:create example, we

did not specify what kind of archetype the goal was to create on our

command line; we simply passed in a groupId and

an artifactId. This is our first brush

with convention over configuration.

The convention, or default, for the create goal

is to create a simple project called Quickstart. The

create goal defines a configuration property

archetypeArtifactId that has a default value of

maven-archetype-quickstart.

The Quickstart archetype generates a minimal project shell that

contains a POM and a single class. The Archetype

plugin is far more powerful than this first example suggests, but it

is a great way to get new projects started fast. Later in this book,

we’ll show you how the Archetype plugin can be used to generate more

complex projects such as web applications, and how you can use the

Archetype plugin to define your own set of projects.

The core of Maven has little to do with the specific tasks involved in your project’s build. By itself, Maven doesn’t know how to compile your code or even how to make a JAR file. It delegates all of this work to Maven plugins like the Compiler plugin and the Jar plugin, which are downloaded on an as-needed basis and periodically updated from the central Maven repository. When you download Maven, you are getting the core of Maven, which consists of a very basic shell that knows only how to parse the command line, manage a classpath, parse a POM file, and download Maven plugins as needed. By keeping the Compiler plugin separate from Maven’s core and providing for an update mechanism, Maven makes it easier for users to have access to the latest options in the compiler. In this way, Maven plugins allow for universal reusability of common build logic. You are not defining the compile task in a build file; you are using a Compiler plugin that is shared by every user of Maven. If there is an improvement to the Compiler plugin, every project that uses Maven can immediately benefit from this change. (And, if you don’t like the Compiler plugin, you can override it with your own implementation.)

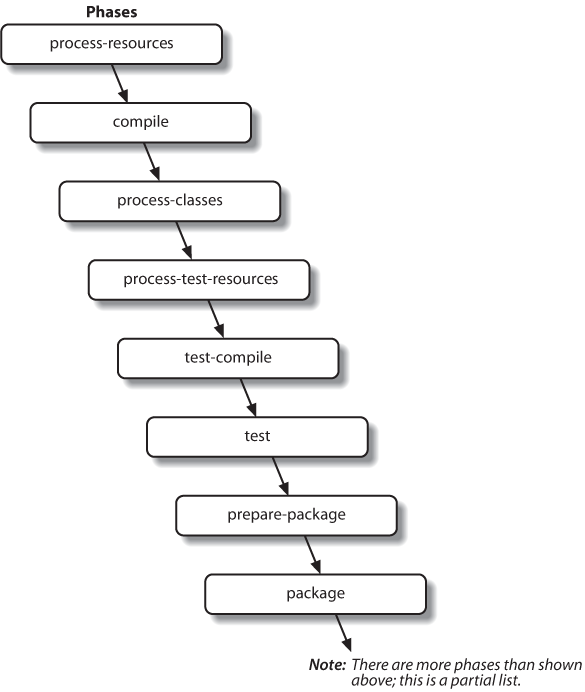

Maven Lifecycle

The second command we ran in the previous section was mvn install.

This command didn’t specify a plugin goal; instead, it specified a

Maven lifecycle phase. A phase is a step in what Maven calls the

“build lifecycle.” The build lifecycle is an ordered sequence of

phases involved in building a project. Maven can support a number of

different lifecycles, but the one that’s most often used is the

default Maven lifecycle, which begins with a phase to

validate the basic integrity of the project and ends with a phase

that involves deploying a project to production. Lifecycle phases

are intentionally vague, defined solely as validation, testing, or

deployment, and they may mean different things to different

projects. For example, the package phase in a

project that produces a JAR, means “package this

project into a JAR”; in a project that produces a web application,

the package phase may produce a

WAR file. Figure 3-2

shows a simplified representation of the default Maven

lifecycle.

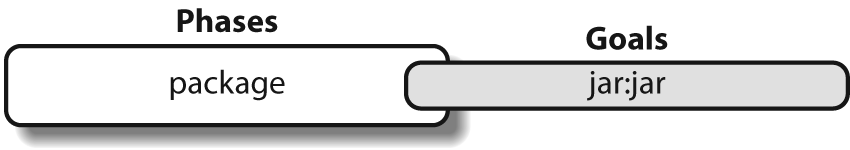

Plugin goals can be attached to a lifecycle phase. As Maven moves through the

phases in a lifecycle, it will execute the goals attached to each

particular phase. Each phase may have zero or more goals bound to

it. In the previous section, when you ran mvn install, you might have noticed that

more than one goal was executed. Examine the output after running

mvn install and take note of the

various goals that are executed. When this simple example reached

the package phase, it executed the

jar goal in the Jar plugin. Since our simple

Quickstart project has (by default) a jar

packaging type, the jar:jar goal is bound to the

package phase (see Figure 3-3).

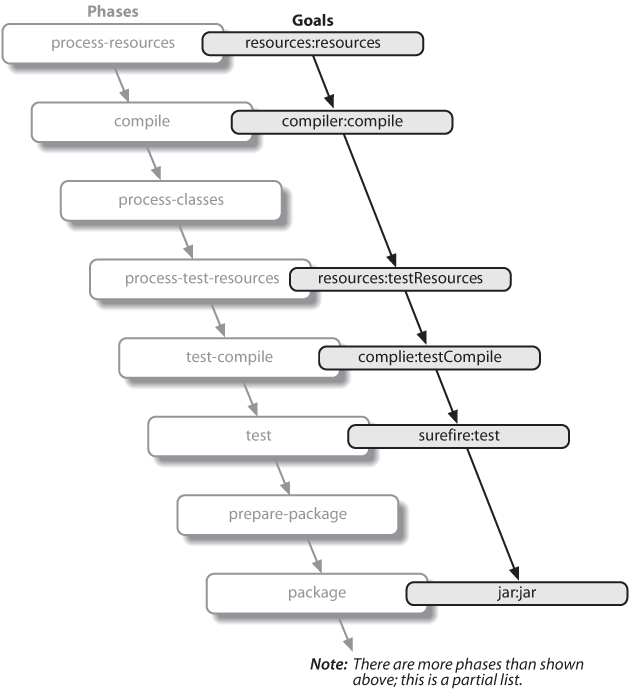

We know that the package phase is going to

create a JAR file for a project with

jar packaging. But what of the goals preceding

it, such as compiler:compile and surefire:test? These goals are

executed as Maven steps through the phases preceding

package in the Maven lifecycle; executing a phase will first execute

all proceeding phases in order, ending with the phase specified on

the command line. Each phase corresponds to zero or more goals, and

since we haven’t performed any plugin configuration or

customization, this example binds a set of standard plugin goals to

the default lifecycle. The following goals are executed in order

when Maven walks through the default lifecycle ending with

package:

resources:resourcesThe

resourcesgoal of the Resources plugin is bound to theprocess-resourcesphase. This goal copies all of the resources from src/main/resources and any other configured resource directories to the output directory.compiler:compileThe

compilegoal of the Compiler plugin is bound to thecompilephase. This goal compiles all of the source code from src/main/java or any other configured source directories to the output directory.resources:testResourcesThe

testResourcesgoal of the Resources plugin is bound to theprocess-test-resourcesphase. This goal copies all of the resources from src/test/resources and any other configured test resource directories to a test output directory.compiler:testCompileThe

testCompilegoal of the Compiler plugin is bound to thetest-compilephase. This goal compiles test cases from src/test/java and any other configured test source directories to a test output directory.surefire:testThe

testgoal of the Surefire plugin is bound to thetestphase. This goal executes all of the tests and creates output files that capture detailed results. By default, this goal will terminate a build if there is a test failure.jar:jarThe

jargoal of the Jar plugin is bound to thepackagephase. This goal packages the output directory into a JAR file.

To summarize, when we run mvn

install, Maven executes all phases up to

install, and in the process of stepping through

the lifecycle phases, it executes all goals bound to each phase (see

Figure 3-4). Instead

of executing a Maven lifecycle goal, you could achieve the same

results by specifying a sequence of plugin goals as follows:

mvn resources:resources

compiler:compile

resources:testResources

compiler:testCompile

surefire:test

jar:jar

Executing the package phase is preferable

to keeping track of all of the goals involved in a particular build.

It also allows every project that uses Maven to adhere to a

well-defined set of standards. The lifecycle is what allows a

developer to jump from one Maven project to another without having

to know very much about the details of each particular project’s

build. If you can build one Maven project, you can build them

all.

Maven Coordinates

The Archetype plugin created a project with a file

named pom.xml. This is

the Project Object Model (POM), a declarative

description of a project. When Maven executes a goal, each goal has

access to the information defined in a project’s

POM. When the jar:jar goal

needs to create a JAR file, it looks to the

POM to find out what the JAR file’s name is. When

the compiler:compile task compiles Java source

code into bytecode, it looks to the POM to see if

there are any parameters for the compile goal. Goals execute in the

context of a POM. Goals are actions we wish to

take upon a project, and a project is defined by a

POM. The POM names the

project, provides a set of unique identifiers (coordinates) for a

project, and defines the relationships between this project and

others through dependencies, parents, and prerequisites. A

POM can also customize plugin behavior and supply

information about the community and developers involved in a

project.

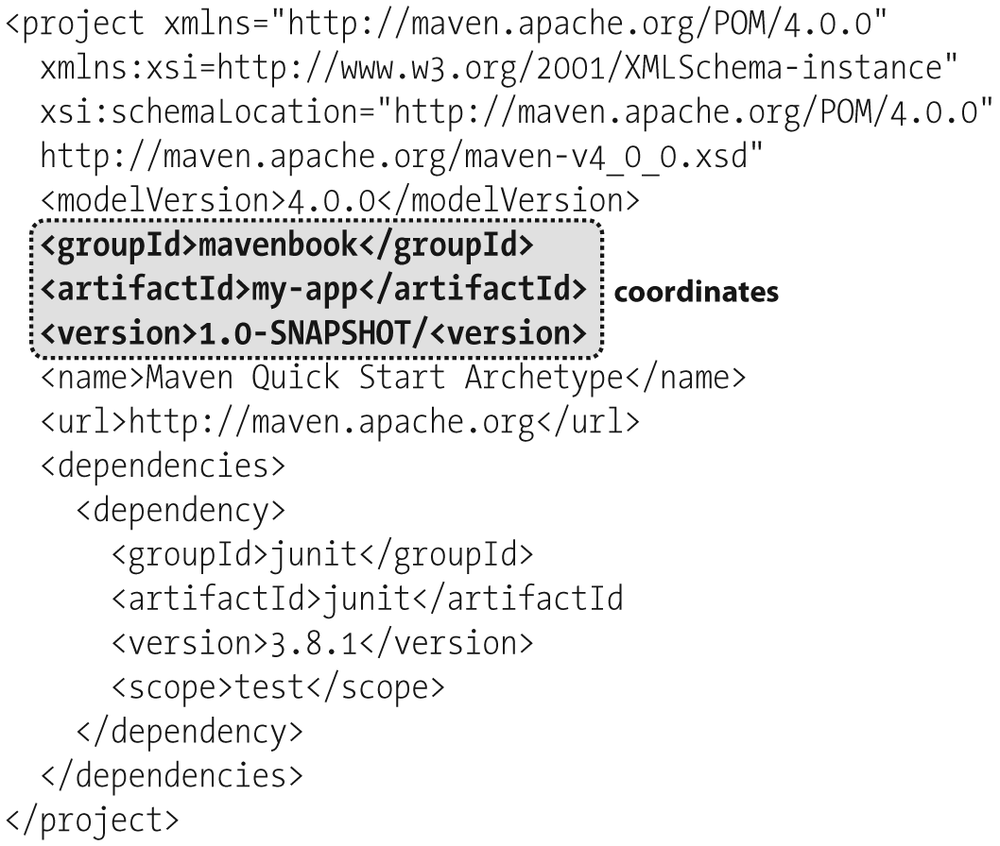

Maven coordinates define a set of identifiers that can be used to uniquely identify a project, a dependency, or a plugin in a Maven POM. Take a look at the POM shown in Figure 3-5.

We’ve highlighted the Maven coordinates for this project:

groupId, artifactId, version and

packaging. These combined identifiers make up a

project’s coordinates.[3] Just as in any other coordinate system, a Maven

coordinate is an address for a specific point in “space”: from

general to specific. Maven pinpoints a project via its coordinates

when one project relates to another, either as a dependency, a

plugin, or a parent project reference. Maven coordinates are often

written using a colon as a delimiter in the following format:

groupId:artifactId:packaging:version. In the pom.xml file for our current project, its

coordinate is represented as

mavenbook:my-app:jar:1.0-SNAPSHOT. This notation also

applies to project dependencies. Our project relies on JUnit version

3.8.1, and it contains a dependency on

junit:junit:jar:3.8.1. Here is some more

information about each part of the coordinate:

groupIdThe group, company, team, organization, project, or other group. The convention for group identifiers is that they begin with the reverse domain name of the organization that creates the project. Projects from Sonatype would have a

groupIdthat begins with com.sonatype, and projects in the Apache Software Foundation would have agroupIdthat starts with org.apache.artifactIdA unique identifier under

groupIdthat represents a single project.versionA specific release of a project. Projects that have been released have a fixed version identifier that refers to a specific version of the project. Projects undergoing active development can use a special identifier that marks a version as a

SNAPSHOT.

The packaging format of a project is also an important

component in the Maven coordinates, but it isn’t a part of a

project’s unique identifiers. A project’s

groupId:artifactId:version make

that project unique; you can’t have a project with the same three

groupId, artifactId, and

version identifiers.

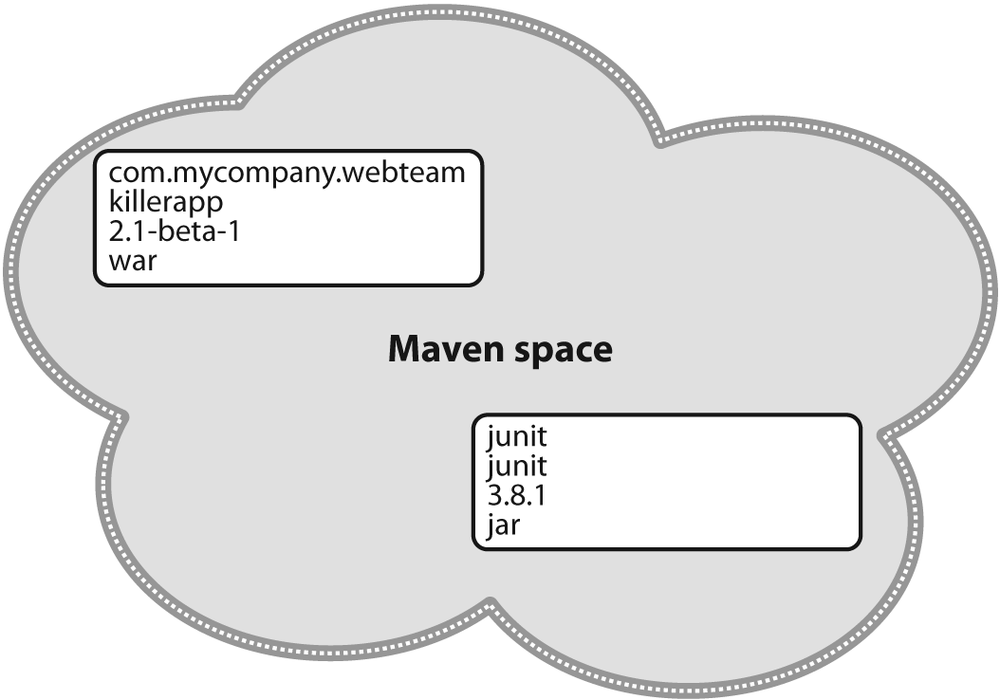

These four elements become the key to locating and using one particular project in the vast space of other “Mavenized” projects (see Figure 3-6). Maven repositories (public, private, and local) are organized according to these identifiers. When this project is installed into the local Maven repository, it immediately becomes locally available to any other project that wishes to use it. All you must do is add it as a dependency of another project using the unique Maven coordinates for a specific artifact.

Maven Repositories

When you run Maven for the first time, you will notice that

Maven downloads a number of files from a remote Maven repository. If

the simple project described in this chapter is the first time you

run Maven, the first thing it will do is download the latest release

of the Resources plugin when it triggers the

resources:resource goal. In Maven, artifacts and

plugins are retrieved from a remote repository when they are needed.

One of the reasons the initial Maven download is so small (1.5 MiB)

is that Maven doesn’t ship with much in the way of plugins. Maven

ships with the bare minimum and fetches from a remote repository

when it needs to. Maven ships with a default remote repository

location (http://repo1.maven.org/maven2),

which it uses to download the core Maven plugins and

dependencies.

Often you will be writing a project that depends on libraries that are neither free nor publicly distributed. In that case, you will either need to set up a custom repository inside your organization’s network or download and install the dependencies manually. The default remote repositories can be replaced or augmented with references to custom Maven repositories maintained by your organization. Multiple products are available that allow organizations to manage and maintain mirrors of the public Maven repositories.

What makes a Maven repository? It’s defined by structure. A

repository is a collection of project artifacts stored in a

structure and format that can be easily understood by Maven.

Everything is stored in a directory structure that closely matches a

project’s coordinates. You can see this structure by opening up a

web browser and going to the central Maven repository at http://repo1.maven.org/maven2/. You will notice that

an artifact with the coordinates

org.apache.commons:commons-email:1.1 is available

under the directory /org/apache/commons/commons-email/1.1/ in

a file named commons-email-1.1.jar. The standard for a

Maven repository is to store an artifact in a directory relative to

the root of the repository:

/<groupId>/<artifactId>/<version>/<artifactId>-<version>.<packaging>

Maven downloads artifacts and plugins from a remote repository

to your local machine and stores these artifacts in your

local Maven repository. Once Maven has downloaded an artifact from

the remote repository, it never needs to download that artifact

again, as Maven will always look for the artifact in the local

repository before looking elsewhere. On Windows XP, your local

repository is likely in C:Documents and

SettingsUSERNAME.m2

epository, and on Windows Vista,

your local repository is in C:UsersUSERNAME.m2

epository. On

Unix systems, your local Maven repository is available in ~/.m2/repository. When you build a

project such as the simple one you created in the previous section,

the install phase executes a goal that installs

your project’s artifacts in your local Maven repository.

In your local repository, you should be able to see the artifact created by your simple project. If you run the mvn install command, Maven will install our project’s artifact in your local repository. Try it:

$ mvn install

...

[INFO] [install:install]

[INFO] Installing .../simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar to

~/.m2/repository/org/sonatype/mavenbook/simple/1.0-SNAPSHOT/

simple-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar

...As you can see from the output of this command, Maven

installed our project’s JAR file into our local

repository. Maven uses the local repository to share dependencies

across local projects. If you develop two projects—project-a and project-bproject-b depends on the artifact produced

by project-a, Maven will retrieve

project-a’s artifact from your

local repository when it is building project-b. A Maven repository is both a

local cache of artifacts downloaded from a remote repository and a

mechanism for allowing your projects to depend on each other.

Maven’s Dependency Management

In this chapter’s simple example project, Maven resolved

the coordinates of the JUnit

dependency—junit:junit:3.8.1—to a path in a Maven

repository: /junit/junit/3.8.1/junit-3.8.1.jar. The

ability to locate an artifact in a repository based on Maven

coordinates gives us the ability to define dependencies in a

project’s POM. If you examine the simple

project’s pom.xml file, you

will see that there is a section that deals with dependencies, and that this section

contains a single dependency—JUnit.

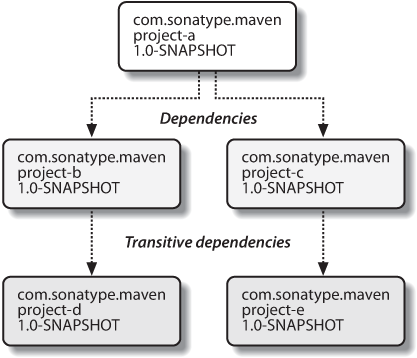

A more complex project would contain more than one dependency, or it might contain dependencies that depend on other artifacts. Support for transitive dependencies is one of Maven’s most powerful features. Let’s say your project depends on a library that, in turn, depends on 5 or 10 other libraries (Spring or Hibernate, for example). Instead of having to track down all of these dependencies and list them in your pom.xml explicitly, you can simply depend on the library you are interested in and Maven will add the dependencies of this library to your project’s dependencies implicitly. Maven will also take care of working out conflicts between dependencies, and provides you with the ability to customize the default behavior and exclude certain transitive dependencies.

Let’s take a look at a dependency that was downloaded to your local repository when you ran the previous example. Look in your local repository path under ~/.m2/repository/junit/junit/3.8.1/. If you have been following this chapter’s examples, there will be a file named junit-3.8.1.jar and a junit-3.8.1.pom file, in addition to a few checksum files that Maven uses to verify the authenticity of a downloaded artifact. Note that Maven doesn’t just download the JUnit JAR file, it also downloads a POM file for the JUnit dependency. The fact that Maven downloads POM files in addition to artifacts is central to Maven’s support for transitive dependencies.

When you install your project’s artifact in the local repository, you will also notice that Maven publishes a slightly modified version of the project’s pom.xml file in the same directory as the JAR file. Storing a POM file in the repository gives other projects information about this project, most importantly what dependencies it has. If Project B depends on Project A, it also depends on Project A’s dependencies. When Maven resolves a dependency artifact from a set of Maven coordinates, it also retrieves the POM and consults the dependencies POM to find any transitive dependences. These transitive dependencies are then added as dependencies of the current project.

A dependency in Maven isn’t just a JAR file; it’s a POM file that, in turn, may declare dependencies on other artifacts. These dependencies of dependencies are called transitive dependencies, and they are made possible by the fact that the Maven repository stores more than just bytecode; it stores metadata about artifacts. Figure 3-7 shows a possible scenario for transitive dependencies.

In this figure, project-a

depends on project-b and project-c, project-b depends on project-d, and project-c depends on project-e. The full set of direct and

transitive dependencies for project-a would be project-b, project-c, project-d, and project-e, but all project-a has to do is define a dependency

on project-b and project-c. Transitive dependencies come in

handy when your project relies on other projects with several small

dependencies (such as Hibernate, Apache Struts, or the Spring

Framework). Maven also provides you with the ability to exclude

transitive dependencies from a project’s classpath.

Maven also provides for different dependency scopes. The

simple project’s pom.xml contains a single

dependency—junit:junit:jar:3.8.1—with a scope of

test. When a dependency has a scope of

test, it will not be available to the

compile goal of the Compiler plugin. It will be

added to the classpath for only the

compiler:testCompile and

surefire:test goals.

When you create a JAR for a project,

dependencies are not bundled with the generated artifact; they are

used only for compilation. When you use Maven to create a

WAR or an EAR file, you can

configure Maven to bundle dependencies with the generated artifact,

and you can also configure it to exclude certain dependencies from

the WAR file using the

provided scope. The provided

scope tells Maven that a dependency is needed for compilation, but

should not be bundled with the output of a build. This scope comes

in handy when you are developing a web application. You’ll need to

compile your code against the Servlet specification, but you don’t

want to include the Servlet API

JAR in your web application’s WEB-INF/lib directory.

Site Generation and Reporting

Another important feature of Maven is its ability to generate documentation and reports. In your simple project’s directory, execute the following command:

$ mvn site

This will execute the site lifecycle phase.

Unlike the default build lifecycle that manages generation of code,

manipulation of resources, compilation, packaging, etc., this

lifecycle is concerned solely with processing site content under the

src/site directories and

generating reports. After this command executes, you should see a

project web site in the target/site directory. Load target/site/index.html and you should see

a basic shell of a project site. This shell contains some reports

under “Project Reports” in the lefthand navigation menu, and it also

contains information about the project, the dependencies, and

developers associated with it under “Project Information.” The

simple project’s web site is mostly empty, since the

POM contains very little information about itself

beyond a coordinate, a name, a URL, and a single

test dependency.

On this site, you’ll notice that some default reports are available. A unit test report communicates the success and failure of all unit tests in the project. Another report generates Javadoc for the project’s API. Maven provides a full range of configurable reports, such as the Clover report that examines unit test coverage, the JXR report that generates cross-referenced HTML source code listings useful for code reviews, the PMD report that analyzes source code for various coding problems, and the JDepend report that analyzes the dependencies between packages in a codebase. You can customize site reports by configuring which reports are included in a build via the pom.xml file.

Summary

In this chapter, we have created a simple project, packaged the project into a JAR file, installed that JAR into the Maven repository for use by other projects, and generated a site with documentation. We accomplished this without writing a single line of code or touching a single configuration file. We also took some time to develop definitions for some of the core concepts of Maven. In the next chapter, we’ll start customizing and modifying our project pom.xml file to add dependencies and configure unit tests.