Lead Advocacy Group: Program Management

Solution requirements specify what needs to be built. Solution designs and project plans specify how to build a solution. The next step is defining actionable tasks from this information and sequencing them to start to form a project schedule. To complete the effort, a schedule needs additional data such as how long will it take to complete the tasks, how the tasks relate, and who will be performing them.

Depending on the size of the effort, each subteam forms their own schedule and integrates them together in a master project schedule. Having a master project schedule provides the same benefits as discussed for having a master project plan (e.g., facilitates concurrent scheduling by various subteams). In addition to subteam schedules, it might be warranted to have cross-team schedules that correspond with projects plans (e.g., training plan). Table 8-13 provides a few examples of these plans and identifies which advocacy group leads the scheduling effort.

Table 8-13. Examples of Typical Cross-Team Schedules

Typical Schedules | Lead Advocacy Group |

|---|---|

Communications schedule | Product Management |

Build schedule | Development |

Training schedule | User Experience |

Test schedule | Test |

Budget schedule | Program Management |

Deployment schedule | Release/Operations |

Purchasing and facilities schedule | Release/Operations |

Pilot schedule | Release/Operations |

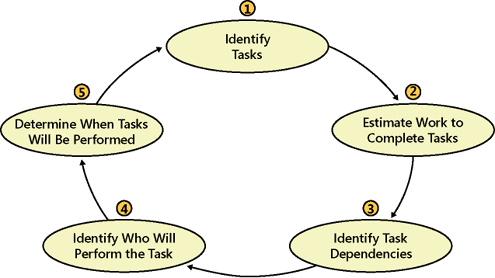

Assembling schedules involves a few steps that should be followed in order, as depicted in Figure 8-9. The first step is to figure out what needs to be done (i.e., tasks). The second step is to estimate the work necessary to complete each task. The third step is to identify task dependencies (i.e., predecessors). The fourth step is to figure out who is to perform each task. The final step is to identify when to perform each task. This iterative process takes a few passes to get all schedule elements balanced and optimally adhering to project constraints and personnel commitments (e.g., vacation, holidays, and training). Each of these steps is discussed in the next few sections.

Guided by project plans, teams must convert requirements and design elements into actionable tasks. It is expected that these tasks will be at different levels of granularity. The goal is to get a consolidated list of tasks that represents all work necessary to deliver a solution. Within the list, the tasks are then sorted by a number of means (e.g., by feature team and then by role). This sorted list is often referred to as a work-breakdown structure (WBS).

While assembling the WBS, it is helpful for later trade-off analysis to assign an overall priority to each task and potentially identify alternate tasks that represent alternate approaches. Later iterations of the scheduling process will eliminate the less favorable alternatives.

With the body of work identified as actionable tasks, the focus changes to estimating how much work is required to complete the tasks. Not to be confused with duration estimating, which is the period of time in which to perform the work (discussed in step 5), the estimated work is a measure of how long it would take one person with the benchmarked skills to complete the task. It is important to understand why the estimates need to be calibrated to some benchmark. If one person estimates the task given his or her own skills but another person with different skills is assigned the task, it is highly unlikely that the estimate is valid. Typically, a team agrees to a benchmarked set of skills when developing the estimates.

Many good approaches can be used to derive estimates—too many to cover here. Here is a quick summary of some commonly used approaches:

Program, Evaluation, and Review Technique (PERT). A mathematically derived estimate based on an optimistic, expected, and pessimistic estimate

Delphi. An estimate based on expert opinion

Parametric. An estimate based on actuals from other projects doing similar activities

Prototyping. An estimate derived from performing a limited portion of the scope to get a sense of how to estimate the remainder of the tasks

These approaches are used in top-down or bottom-up estimating. Commonly, the Product Management and Program Management teams drive a top-down view of the estimates to reflect the various project constraints, whereas team members drive a bottom-up approach. It is healthy to compare and contrast these two opposing approaches because the process often uncovers requirements gaps, readiness gaps, mismatched stakeholder expectations, and unrealistic project constraints.

Having team members estimate their own tasks is an important aspect of team empowerment. That way, the people doing the work make commitments as to when it will be done. The result is a schedule that the team supports because they believe in it. MSF team members are confident that any delays will be reported as soon as they are known, thereby freeing team leads to play a more facilitative role, offering guidance and assistance when it is most critical. The monitoring of progress is distributed across the team and becomes a supportive rather than a policing activity.

A task dependency exists when other tasks must be started or completed before the task in question can start or be completed. For example, the install Microsoft Windows operating system task needs to come before the install Microsoft Exchange Server task. It is important for team members to define their tasks in consideration of what else is needed to perform the tasks (i.e., task dependencies). This is especially important when dependencies cross team boundaries—the other team might not know of the dependency and might overlook it.

Adding dependencies is not as simple as sequencing tasks. It also includes identifying situations where it is prudent to delay tasks (i.e., waiting with no planned activity before starting a task). For instance, after a server build, it is prudent to wait a short time to make sure the server is operating as expected before performing other tasks with that server—often called a "burn-in" period. These quiet periods do not show up as tasks. Rather, the time is built into the dependencies. For instance, a task of hanging a picture (task 2) on a newly painted wall can start no earlier than two days after completing the painting task (task 1). Needing to wait while the paint dries is not a task. It is a condition placed on the association of the two tasks (i.e., task 2 is dependent on the successful completion of task 1, plus a minimum of an additional 2 days).

At this point, the team has identified and estimated tasks and has identified cross-task dependencies. The focus changes to evenly distributing the work among the available resources.

A few approaches can be used to assign resources. One approach for the first pass is to assign a role title for each task (e.g., Senior Exchange Engineer 1). Later on, these role placeholders are replaced with team member names. This is helpful if team members are playing multiple roles. Putting role placeholders first enables a team to think about what is needed and helps them avoid getting caught up with specific team member skills and constraints (e.g., availability). Cost might also be a consideration. Putting role titles first is often much easier to change later than is assigning specific team member names (e.g., when project cost constraints necessitate using a less senior resource).

Another approach is to make resource assignments based on small subteams (e.g., commonly called work streams). With this approach, work is assigned to a work stream team, and the work stream lead is empowered to manage the assignments among the subteam handling the work stream—providing team cohesion. This approach of balancing work among work stream teams is much easier than balancing among individual team members.

Up until now, the scheduling process has not been influenced by project trade-off matrix decisions. As such, task start and finish dates have floated to be what was dictated by the sequencing effort. If the lowest trade-off priority from the Project Trade-off Matrix (discussed in Chapter 7) is schedule, the schedule is what it is, and therefore scheduling is done. However, this is rarely the case. This step focuses on adjusting these dates to fit date-oriented project constraints.

Many approaches to compressing a schedule can be used to make the schedule fit within date-oriented project constraints (commonly called "crashing the schedule"). The best guidance on how to proceed is to reference the priorities specified in the trade-off matrix. If features are a higher priority than resources are, adding resources is the best course of action. Otherwise, removing features is the best course of action.

Another aspect of determining when tasks will be performed is to look at the environmental constraints. For example, organizations often have "black-out" or "freeze" periods where no production changes happen (e.g., accountant organizations often declare a few months prior to tax day a period where no production changes are tolerated).

Lead Advocacy Group: Program Management

In addition to balancing schedule elements on each subteam, the elements need to be integrated and balanced across a project. The cross-project elements and activities are consolidated, integrated, and balanced within a master project schedule.

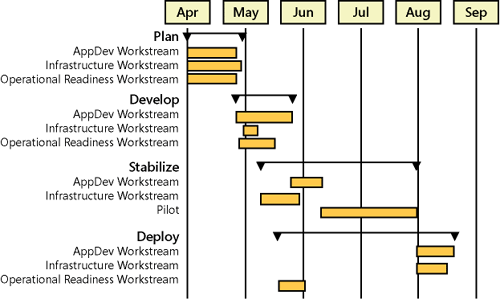

The master project schedule integrates the various subteam schedules needed to deliver a solution. It typically calls out significant tasks, deliverables, and checkpoints, providing an overview of a project. Figure 8-10 is an example of a project schedule summary with three work streams.