CHAPTER 5

Value Growth and Optimizationa

As mentioned in Chapter 4, a common theme throughout this book is the need for owners and shareholders to increase the value of their businesses and position them to capture that value in a future transaction—value growth and optimization. Value growth and optimization are important whatever the transaction—whether the company is being sold or is making an acquisition, whether it is seeking financing for growth or for recapitalization as a sale. In this chapter we discuss some of the key levers or factors that impact value and that might allow a company to increase the realizable multiple applied to cash flow by a buyer or investor in a transaction, or allow it to obtain more capital to fund its future plans. For private middle market companies, value creation is principally based on long‐term, expected future cash flow. In practice, the activities that lead to value creation are nearly the same whether preparing for a financing, a wave of growth, or an M&A transaction.

Owners of private companies tend to avoid debt and manage the business to minimize taxes and maximize the current cash benefit to the shareholders. While this approach makes sense in the short term, it often overweights decisions and strategies for immediate impact at the expense of what outside investors or lenders would consider long‐term value creation. Many times, improving the realizable value of a company means shifting its approach and pursuing value creation in a more proactive way. Taking a proactive stance means, among other things, that a company will tackle tough issues and instill disciplines like those on which an institutional investor would insist. It also means taking a long‐term view about investments in assets and capabilities. A useful question for management to ask in readying their company for change is “With access to capital and professional management, what would a buyer do to improve my business?” The answer to that question will likely provide keen insights and areas of focus, and is what we hope to provide here.

Essential to increasing or growing the value of a company is increasing the amount and certainty of its cash flow while reducing the risk of achieving that cash flow. Optimizing the business should shift the market value of the company toward the upper end of valuation benchmarks and simultaneously increase its alternatives (more buyers, cheaper capital, etc.) when engaging with the capital markets. For clarity, the focus of this chapter is on increasing the value that a buyer or investor would attribute to a company, resulting in a higher purchase price in a transaction. Our discussion here hinges on those value levers most critical to the optimization of private, middle market companies from the perspective of those in the capital markets, including institutional investors, private equity firms, lenders, and strategic buyers. The actions we describe here would produce benefits in almost any capital markets transaction, even one as simple as obtaining a loan to finance organic growth.

As we begin this analysis, keep in mind that strategic decisions need to be thought of and developed using the priorities from Chapter 4 and by aligning the company's long‐term growth strategy with the right leadership team, with the appropriate entity and organizational structure supported by scalable systems, and capitalized by the proper funding sources. Management must also consider changes to a company relative to its stage and life cycle within its specific market.

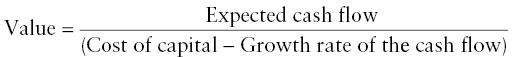

Calculating the value of a stream of cash flow can be viewed in mathematical terms by this simplified formula.b

The expected cash flow is the value stream that would be presented to buyers or investors, and is most often normalized EBITDA less the amount of capital required for reinvestment to grow the company. According to this equation, we can increase the company value by increasing the absolute value of the cash flow; reducing the cost of capital; or increasing the rate of growth of the cash flow (or any combination of the three). Reducing the cost of capital is, in part, directly related to the risk of achieving that cash flow. Embedded in the concept of reinvestment for growth is the base amount of capital required to operate the company. This is the connection with the concept in lever 1, return on invested capital, in the following list.

To frame the discussion and apply some basic corporate finance concepts, we will look at value creation and optimization as an exercise with three distinct types of value levers (or factors that management can influence).c The first provides a check on the balance between cash generation and the underlying investment required to generate that cash. The second deals with risk, and the third primarily addresses the practical aspects of transferring a business:

- Pursuit of strategies that increase the return on invested capital.

- Pursuit of strategies that reduce the risk of investment in the company.

- Pursuit of tactics and strategies that ease the transfer and reduce the impediments and obstacles to transitioning a business to new owners (whether transferred in part or in whole).

Keep in mind that certain businesses do not generate positive cash flow in the early phase of their lifecycle but do create significant inherent value. From a buyer or investor perspective, these companies may have captured (or are capturing) a significant customer base or developing a technology that will eventually lead to relatively large and material cash flows. The discussion and concepts still apply.

INCREASING THE RETURN ON INVESTED CAPITAL

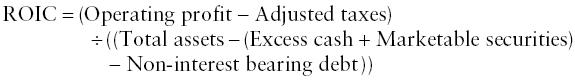

One way to measure return on invested capital (ROIC) is to divide (i) net operating profit less adjusted taxes by (ii) total assets excluding excess cash and marketable securities, minus non‐interest‐bearing liabilities.1

To increase the ROIC, a company can either increase its operating profits and cash flow while maintaining the same level of invested capital or reduce the amount of invested capital while maintaining the same operating profit and cash flow. Under ideal circumstances, management can do both simultaneously.

In the following subsections, we discuss five key levers that can work to manage, control, and increase the ROIC. The primary outcome of moving these levers should be increased cash flow and improved capital efficiency; however, a possible secondary effect of moving these levers is an increase in the rate of growth of that cash flow (which directly increases value, as shown in the first equation in this chapter). Preparation for both growth and an M&A transaction includes developing and prioritizing appropriate initiatives to optimize the ROIC of the company given the risk profile and ambitions of the shareholders. As a company optimizes its ROIC, it is likely to also experience improved operating metrics, such as better‐than‐industry‐average gross and EBITDA margins and faster growth as compared to its peers, both of which contribute to greater value.

Strategic Position

The strategic position of a company is essentially its competitive stance relative to its peers and industry or market segment. The better a company's strategic position, the greater its ability to win and maintain business and to add value for its customers. At a minimum, management should (i) understand the market and the company's competitive position, and (ii) evidence and validate the company's relative position. Third‐party validation is often helpful in addressing both of the aforementioned; for example, specialized industry or segment reports that highlight a company can be useful, assuming that the company is in a strong position. Industry awards and recognition are another means to validate strategic position. A company in a weak or average position may need to implement initiatives to create a stronger position or reposition to a sustainable posture.

Middle market companies (and not only middle market companies) will benefit by applying more rigor to this assessment of their strategic position than they often do. They tend to see the playing field as being occupied only by their direct competitors and may underestimate the threat from new entrants or changes in competitive dynamics, for example. They may also be less attuned than they should be to how even the rivals they know are changing. Many excellent frameworks can be used to analyze competitive position, such as Michael E. Porter's gold standard Five Forces framework.2

In today's world, few companies can thrive in a vacuum, so creating a network of alliances or partnerships can help to gain advantage in a marketplace. Alliances or partnerships might provide cost or supply advantages, unique capabilities, desired sales channels, or access to technologies that competitors can't easily duplicate. These relationships can improve the competitive position of a company and provide evidence of the value of that company, particularly if the alliance or partnership is with a recognizable industry player. Some alliances allow companies to make use of assets on a partner's balance sheet (such as production or distribution facilities), thus reducing a business's capital intensity, potentially increasing its return on invested capital. Partners with data‐gathering and analytics solutions may help a company create new opportunities to increase revenue, for example by identifying new potential prospects, customers, and other partners or by revealing previously hidden opportunities to serve existing customers.

Ideally, a company's strategic position will logically fit and address the industry or sector trends and play into them in a way that is advantageous going forward. Whether the company's strategic position has recently emerged, has slowly evolved, or is well entrenched, being able to articulate and leverage that position is an important part of the growth story and the foundation upon which to build an operating strategy.

Customer Base

The competitive and strategic position of a business is linked to its customer base. As a company transitions from one stage of growth to another, the customer base evolves. One goal in optimizing the value of the business at the time of a transaction is to establish a customer base that appreciates the value the company provides and is willing to pay for it. Does the company have a customer base that it can build upon and grow with? Do these customers fit the profile of what can be thought of as ideal customers? What percentage of a company's revenue comes from recurring business?

Since a buyer or investor is paying for future cash flow, they will pay significant attention to the quality of revenues, earnings, and cash flow. The strength of a company's customer base—which obviously is the driver of revenues and, therefore, cash flow—can greatly influence the quality of earnings and cash flow and how well they represent future projections based on the strategy of the business. The process of improving the quality of revenues and earnings may very well include culling customers that are problematic, low margin, slow paying, or who otherwise consume resources or products/services that aren't core to the future of the business and replacing these customers with those who more closely fit the ideal profile. To improve the value of the business is to more tightly align the customer base with the growth strategy, giving it a higher quality of revenues and earnings.

Cost Structure and Scalability

As with the customer base, the operations of a company should be configured in the context of its overall growth strategy. From a buyer or investor perspective, these decisions could include outsourcing noncore activities, automating processes, optimizing the mix of contract versus permanent employees, and improving utilization of facilities. It also could mean installing and maintaining first‐rate IT and cybersecurity defenses. Any of these changes can have an impact on the cost of goods and services, research and development, sales, and general and administrative expenses, and they should be synchronized with the growth strategy and the stage of the company.

To create operating leverage, management might explore how the structure of a specific operating area or capability within the company could allow the business to ramp up its revenues and output disproportionally to the required investment or expense. The greater the disproportionality, the greater the scalability implied, particularly where the contribution margin of incremental revenues grows as the business grows. With a high‐growth business, this scalability would likely be seen as creating additional enterprise value. Some software companies, for example, have transitioned away from the traditional enterprise model and adopted a software‐as‐a‐service model, in which a significant number of new customers can be added with relatively minimal new costs, creating a dramatic impact to valuation. This is one of the reasons that companies such as Meta (formerly Facebook) have such high valuations: Viral customer acquisition is often self‐perpetuating, and the incremental cost to serve them is close to zero. Economies of scale or scope have always driven business valuation, but in the digital world they are available in new and creative ways, often to the benefit of middle market companies. The ability to target advertising on the web, to take one example, has taken away some of the marketing scale advantages that big companies with big ad budgets once enjoyed.

Working Capital

In accounting terms, working capital is equal to current assets minus current liabilities. In practical terms, it is the money that needs to be tied up to operate the business. In middle market M&A transactions (those beyond the small, Main Street asset deals), the selling company is typically expected to deliver a normalized level of working capital to support the operations of the business post‐closing. Calculating the working capital and figuring the basis for the analysis is somewhat of an art and often changes depending on the norms within a specific industry. It is also changing as the digitalization of payments has, by and large, shortened the order‐to‐cash cycle for healthy companies. Historical trends can be a sound baseline for establishing the target amount. The argument that a buyer can operate the seller's company with less working capital than the seller can is hard to defend without evidence. In growth financings, tightening the working capital cycle can provide a cheap and quickly accessed source of funding. In both M&A and growth financing, optimizing the working capital cycle and assuring the efficient use of this capital will increase the value of the business by decreasing or minimizing the capital required to fund the operating cycle—the financial equivalent of driving a car that gets more miles per gallon.

Modifying the working capital cycle within a company can touch many aspects of the business. The approach and ability to make these changes depends, in some part, on the relative strategic and competitive strength of the company and the desirability of its products or services. This is where we connect the dots from the previous discussions. Typical areas for tightening the working capital cycle include accelerating customer payment or requiring prepayment, extending supplier credit terms to market norms, increasing inventory turns, and reducing the overall operating or process cycle times. When a seller in an M&A transaction tightens the working capital cycle for a year or two prior to a sale, they demonstrate that the new norm is sustainable. From a buyer's perspective, this tightened working capital cycle can reduce the risk associated with estimations when negotiating the working capital target. Not tightening the working capital cycle is, in effect, giving the buyer money or reducing the purchase price.

Human Capital

Engaging and developing the human resources of a company is the final lever to highlight in our discussion about increasing the return on invested capital. In fact, human capital is often the greatest investment that a business makes. To realize the highest value for this investment, management should focus on three interrelated areas: continuous improvement, incentives, and culture. A company's ability to grow and thrive is directly linked to its ability to attract, retain, and reward employees while engendering a sense of ownership and accomplishment at all levels. When optimized, the integration of these three areas should result in a culture of innovation, reduced costs, improved operating efficiencies, and the institutionalization of the knowledge and wisdom of the business into the processes and systems of the organization.3

REDUCING THE RISK OF INVESTMENT

Risk is defined as the variability of an expected return over time.4 Once a buyer or investor has bought into the company's growth story or established an investment thesis and determined that the potential outcomes are within an acceptable range, the focus of the analysis turns to risk mitigation and sharing, that is, sharing the risks between the buyer and seller for a period of time beyond closing the deal. Proactively reducing or mitigating these risks can increase the value of the company. A reduction in the risks of the business should result in a reduced cost of capital or lower expected variability from the target return on investment and, thus, greater implied value in the cash flow. This leads the owner to pursue strategies that reduce the risk of investment in the company.

In practice, lowering perceived risks helps establish and build confidence throughout the transaction process and decreases discounts or hedging by the buyer or investor in pricing the business. The goal is to demonstrate the possible value streams (which will eventually become cash flow) generated by acquisition of, or investment in, the company and to provide indicators that give confidence and increase the certainty of achieving them.

In this discussion of risk, remember that private, middle market companies are not managed in the same way as public and larger businesses. In private, middle market companies, nonfinancial owner and shareholder ambitions and interpersonal sensitivities directly affect management's actions and willingness to confront tough situations or make changes that on the surface might otherwise make logical or strategic sense. Often, difficult situations are not addressed until a change of ownership or a crisis spurs improvement. In fact, the need to make tough decisions often drives the change of ownership. The proactive acknowledgment of this dynamic in itself can set the stage for releasing unrealized value within a company, if not by making tough decisions, then by understanding what the difficult decisions are and presenting the investment opportunity as part of the solution. Leaving the hard decisions and change management up to a buyer or investor is risky from their perspective, and will likely reduce the realizable value of the company. It is good practice, therefore, to reduce a company's risk prior to a transaction by implementing changes that address its critical challenges or issues.

The following discussion highlights some of the key areas of risk that tend to surface in mergers, acquisitions, and financings of private, middle market companies and outlines initiatives or actions that can be taken to reduce those risks and increase the value of the enterprise.

Awareness and Planning

Few companies have fully optimized operations. As companies move through their lifecycle, their risks and opportunities change, so the task of managing risk is always in a state of flux. The first step in reducing the risk of buying or investing in a company is to understand the risks inherent in the type of business and the market in which it operates. The second step is to understand the distinct risks that are specific to the individual company. If the past years have taught us anything, it is that companies can prepare better for operational, technology, supply‐chain and distribution, and market risks than they often do. A combined understanding provides the basis for assessing the overall risk profile and for plotting a path forward. During the transaction process, the price and deal terms can hinge on management's ability to clearly articulate what is being purchased or invested in and to demonstrate a house truly in order. As mentioned earlier, management that is aware of and acting to mitigate the risks of their business can provide some comfort to outsiders who may have concerns about undisclosed or latent issues.

Growth Plans and Relative Position

Understanding and optimizing a company's strategic position can provide the focus for important operating decisions. Improved positioning relative to competition should increase long‐term cash flow and reduce risk as it relates to the company's relevance in its market. At the minimum, a company should understand its growth scenario as a standalone entity. But the context of a potential acquisition or significant infusion of capital opens the door to thinking about a breakout strategy as well. While the standalone scenario should show sustainable growth based on the company's current capitalization and earnings, a well‐thought‐out and validated breakout strategy can be used as a negotiating lever for extracting additional value for a company beyond what its current cash flow might justify. For example, a company planning significant geographic expansion as its breakout strategy—a strategy that requires capital or resources to fully implement—will want to have actually expanded on its own, in at least a small way, to demonstrate the scalability of the business. Further successful expansion could be the basis for earnout or milestone payments in the context of a sale of the company.

Leadership Team

In evaluating and reducing the risk related to the leadership and management of a company, one must look first at the organization's dependence on the CEO, owner, or entrepreneur and then at the strength of the organization's leadership bench. A company with a hands‐on CEO who makes all the decisions supported by functional managers is usually riskier than a company led by a CEO who operates among a team of leaders with individual decision‐making authority and are accountable to near‐real‐time performance metrics. Midsized companies may also be dependent on a handful of key technical or other employees whose departure would significantly weaken the company. From a macro perspective, a qualitative assessment can be made by answering a few core questions:

- Is the current leadership team organizationally healthy, functioning, and capable of growing the business to the next level?

- Have key relationships with suppliers and customers been developed with multiple members of the leadership team?

- Has the team developed a positive culture and organization that learns and improves?

- Have any of the key members of this team experienced or led a company through this type of growth and operated at the next level?

- Are members of this team functionally learning on the job or do any have domain and industry experience?

- How successful has the team been in attracting, developing, and retaining others?

- Has this team operated successfully together through a difficult time or situation?

- What has been the recent performance of the company under the leadership of this team?

- Is there an incentive for the team to perform and stay with the company beyond a transaction?

Developing a leadership team that enables a positive response to these questions and that can operate the company without need of any specific individual generally reduces the risk of investment in that company.

This kind of leadership and management assessment will resonate with most institutional investors, lenders, and buyers. Nonetheless, many private owners will make the argument that it is riskier for them to hand off responsibility than to directly supervise or perform sensitive functions, such as cash management, key customer relations, and large project management.5 This divergence of perception, and the practical implications that result, is one example of a factor that contributes to a valuation gap. Private owners may also be reluctant to share equity with key employees, although an ownership stake can provide a powerful incentive for them to stay.

Predictability of Revenues and Earnings

Historical financial performance is no guarantee of the future cash flow of a company, but it does provide evidence about the company's level of operating performance and management's ability to lead, which is especially important in times of great uncertainty such as with the Covid pandemic. Generally, predictable revenues and earnings are considered to have greater value and less risk than cyclical, seasonal, or sporadic performance. The business model of a company often dictates the risk associated with predictability. For example, recurring or repeat multiyear, contractual relationships that are likely to continue over the long term and that can be forecasted are most desirable.

A bottom‐up revenue and expense forecast built on historical operating performance and metrics tends to inspire confidence and allows a buyer or investor to understand the value drivers of the business and the associated risks. Future revenues and earnings evidenced by contracts and existing relationships are often less risky than revenues and earnings based on individual new sales from a broad market or new customers. An example of a business between these two extremes is one with a history of sales operations that documents how certain business or selling activities directly correlate to certain customer responses and, in turn, lead to certain types or amounts of new orders. In this scenario, order flow and revenue can be managed and somewhat predicted. While this provides a proven and documented process for obtaining new business, revenue is still generated order by order. To reduce this order‐to‐order type of risk, this business might move to longer‐term, well‐defined contracts that provide a backlog and visibility of demand and revenues.

The variability of costs and their impact on profitability is an important lens through which to evaluate a company's structure, especially for businesses that are seasonal or have episodic revenues. A company that can manage through revenue fluctuations and generate predictable earnings and cash flow is less risky than one with higher fixed costs and less control of its performance.

Concentrations

Concentrations should be identified and evaluated for their risk and possible impact. Examples include customer concentration, supplier concentration, and relationship and employee concentrations, as mentioned earlier. The concept is that of a single point of failure or significant impact that could be detrimental to the performance and/or longevity of the business.

Customer concentration, the phenomenon of one or a few customers contributing a significant volume of revenues and/or consuming a large amount of the company's capacity, is generally considered to be a risk to a company's cash flow stability and, ultimately, longevity. The level at which concentration becomes an issue can change based on industry and circumstances, although 20% or more of annual revenues from one customer is likely to trigger a closer look. A similar risk exists with supplier concentration, especially where few alternatives exist for a critical resource. Having a long‐term contract with strong protective and termination clauses with a significant customer can mitigate the risk of concentration. An even better solution to customer concentration is to obtain more customers and balance the mix of business. Supplier concentration can be mitigated by securing long‐term contracts that provide for committed resources or products, finding a second source of supply or obtaining a co‐right of some type (e.g., a co‐right of production, ownership, or sourcing).

Addressing the risks inherent in concentration will resonate with most institutional investors, lenders, and buyers. However, many business owners will argue that concentration within a few established customers and suppliers where deeply entrenched relationships are formed is less risky than diversification and may enable them to optimize their business's performance.6 Research by NCMM shows that many fast‐growing middle market companies often find themselves closely linked to a handful of key customers—these, after all, may provide the recurring revenue that is strategically valuable. Clearly there is a sweet spot, different for each company and industry, where companies have both deep and well‐managed relationships with a core group of customers, a diverse customer base, and a regular stream of new customers. Again, a divergence of perception about what that sweet spot is, and the practical implications that result, is another factor that contributes to a valuation gap.

Compliance

Unresolved compliance issues involving taxation, pay and benefits, labor laws, and environmental regulations can indirectly affect the risk and value of a company by increasing doubt or decreasing confidence in management's ability or integrity. Where these issues can be identified, the direct impact to the value of a transaction is usually carved out or indemnified separately, thus reducing the potential net cash to the seller or possibly jeopardizing the transaction. Compliance issues often lead to valuation issues when they affect operating costs and earnings. Proactively identifying compliance issues and then developing corrective action plans that contain and resolve the issues begins the process of managing the risk. In some cases, the company will be better off if it resolves compliance issues before engaging in the transaction process. But the presence of such unresolved issues might also lead buyers to worry about not‐yet‐identified problems and cause them to bid more cautiously for a company.

Keeping Current

Some businesses require heavy, ongoing investment to remain relevant and growing. The need to make these critical, known improvements in a business can create uncertainty and risk for a buyer or investor and, in some cases, can be a catalyst for a transaction. Companies that require significant investment to stay current or to update technology, facilities, or equipment are often penalized in a transaction in two ways: (i) the required change is seen as creating additional risk, and (ii) the buyer will often reduce the offer by their estimate of the cash required to make the improvement to the company beyond a normal level of reinvestment. This situation is often found in companies that are undercapitalized, have failed to earn a return great enough to reinvest or to stay current, or in which the owners have stripped the company of its capital or failed to reinvest. Understanding the cause of the failure to remain current in operations or products may allow management to develop a strategy for addressing it for the M&A or financing transaction; the eventual solution is likely very different, depending on the cause.

The ability of a company to innovate is directly related to the concepts just discussed in assessing the strategic risks and opportunities of the enterprise. Is the company built on a single product, technology, or service? Or does it have a track record of successfully responding to market changes and opportunities that provide for longevity, sustainability, and continued relevance? The risk imputed for innovation, or the lack thereof, is a factor and will depend on the specifics of the company, the market in which it operates, and the needs and capabilities of the buyer or investor.

EASE THE TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP

Optimizing enterprise value and preparing for M&A transactions and growth, which often include external financings, may include addressing administrative and entity‐related issues that cause friction in the deal process and effectively increase the risk of closing a transaction. The final concept to address in our analysis is, therefore, “greasing the skids” for a transaction and enabling management to make it simpler and less risky to transfer a company's ownership (in whole or in part). The following discussion outlines typical sources of friction in a transaction and ways to manage them.

Financial Information

The standard for financial reporting and information used for valuation is usually accrual accounting that complies with the U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), depending on the country and agreed‐upon basis for the transaction. Financial statements prepared for tax and management reporting purposes often fail to fully meet these standards, particularly in the lower middle market. A key way to prepare in advance for engaging with the capital markets or for a sale is to compile financial information, both historical and prospective, that allows the parties to directly compare data and that complies with GAAP or IFRS. Typical financial reporting problem areas include: revenue recognition, year‐end payroll and benefit accruals, asset expensing versus depreciation, and normalization adjustments accounting for specific owner‐related benefits.

The objective of preparing financial information is to generate numbers that allow direct comparison of revenue, gross margin, expenses, capital expenditures (CAPEX), and EBITDA amounts and percentages within the conventions of a company's industry. For a business with critical mass or size, having audited or reviewed financial statements from a credible and recognized accounting firm is important and, in some cases, required. Even with reviewed or audited statements in hand, many parties involved in M&A and financing transactions require an additional, external assessment of the timing and value of the cash flow of the business, which is often referred to as a quality‐of‐earnings assessment.

Since value creation is based on future cash flow, it is important to note that capturing, evaluating, and optimizing the true economics of a business include understanding the required future investment in CAPEX. This investment, often excluded from traditional EBITDA metrics, can have a significant impact that needs to be understood to drive value growth.

In addition to traditional financial reporting, there are other kinds of metrics that can provide valuable insight into business operations and allow management (and prospective new owners) to react and adapt to changes. Examples include key performance measures, leading indicators, and operating data.7

Some companies engage advisors to conduct sell‐side due diligence and quality of earnings analysis as part of their planning process in advance of going to market. Having well‐organized and accurate financial information allows the parties to move deliberately and quickly through the analysis, decision, and negotiating phases of the deal and supports the momentum and energy that builds as a transaction process advances. It also gives sellers a chance to identify and fix issues that might trouble buyers before going into the market.

Contracts

One determinant of the ease of transfer of a business is the ease of assignment of its contracts from one owner to another. For businesses with long‐term customer contracts, agreements that are assignable and that don't require a change‐of‐control consent by the customer allow flexibility in determining the deal structure and reduce the risk of disrupting customer relationships during the transition. This assignability challenge is sometimes alleviated in a stock transaction, since the company continues to exist post‐transaction. The same concept applies to various other contracts that a company might have, including employee agreements, supplier contracts, facilities leases, licensing agreements, and debt instruments. Based on the industry, size, and growth stage of the company, management should consider the type of transactions that might benefit its shareholders and shape its agreements accordingly. At the very least, managements contemplating a sale should know what all their contracts say about transferability.

Title to Assets

At some point in the process of completing an M&A transaction or obtaining growth financing, the topic of defining and listing the assets of a business will arise. This requires identifying both tangible assets (e.g., property, plant, and equipment) and intangible assets (e.g., software, trademarks, patents and copyrights, trade secrets, and customer lists). Understanding what a company owns and how much it is worth are factors in determining the structure of a transaction and how the purchase price is allocated (which impacts taxes for both the buyer and the seller). One step in preparing for a transaction is to develop a comprehensive list of a company's assets and establish and provide evidence of clear title. This may involve having liens removed from public records. For intellectual property (IP), it may require filings, registrations, releases, or assignments, depending on the circumstances in which the IP was created. As with other areas of preparation, working through the details of this step can take time. Waiting until the time of a transaction to act can slow the process, undermine buyer confidence, and increase the costs of a deal.

In some cases, families wish to withhold certain assets from a sale (real estate is a common one). Sometimes companies carry assets on their books (cars and boats, for example) that buyers will not want. Owners contemplating a sale should think through these—what their preferences are and what buyers are likely to want—so that they do not become sticking points or distraction in a deal.

Corporate Structure and Attributes

Two common topics that arise when considering the legal entity and structure of a transaction and the interaction with selling shareholders (or members) are (1) tax treatment of the selling entity and (2) approvals by the seller required to effect a transaction.

- Optimizing after‐tax proceeds from M&A transactions usually requires long‐term planning regarding the seller's type of corporate entity and its tax status. Determining if, when, why, and with whom a company is likely to engage in the capital markets can provide some guidance as to whether C‐corp or S‐corp (or partnership, if an LLC) status makes sense for optimizing the value to its owners over time. Changing status on short notice is usually financially punitive and might create practical barriers or negate the economic value as the motivation for a deal, especially for transactions with companies that have marginal performance. Last, be cognizant of complicated entity structures that can create complexity and issues in a transaction process.

- For entities with multiple owners with divergent levels of interest, it is very important to have established who has clear authority to execute a transaction. A typical approach to control is for the majority shareholder(s) to create a formal shareholder agreement (or operating agreement, for LLCs) that provides for drag‐along rights for minority owners. Another approach is to plan ahead and buy out minority, disgruntled, or estranged shareholders well before a transaction is imminent.

Don't Lose Focus on the Core Business

A word of caution: It is important for management to remain focused on company performance while engaging in the process of a transaction or implementing a growth strategy. The time, financial, and emotional investment can be overwhelming during the preparation and negotiation process, and, because of the perceived urgency and critical nature of the demands, normal management responsibilities often suffer, resulting in slower business development and a lack of cost controls, just to name a couple. What can make this issue particularly troublesome in an M&A transaction (or a growth strategy that involves outside funding) is the negative impact to valuation, terms, and conditions of a deal if performance begins to slip. Prior to closing, interim financial statements will often be reviewed to measure company results against projections or expectations. Although some slippage can occur due to the dilution of management attention, poor business performance can affect the terms that the buyer or funding source originally agreed to. The risk is especially high in situations with a protracted negotiating period. To counter this potential, plan ahead and seek to accelerate performance of the company. Be intentional by focusing the operating team on clear goals and establishing a deal team to lead the process.

SUMMARY

In the discussion in this chapter, we outlined the main levers that management of a private, middle market company can control to increase the return on invested capital, reduce the perceived risk of investment, and ease the transfer to new owners for successful M&A transactions and growth initiatives. These relate directly to the company itself. In addition, there are two external influences that will likely affect the outcome of a transaction process and the realized value for the shareholders. We encourage the team to consider these:

- The level of industry transaction activity. In a hot and active deal market, management may find it easier to attract capital, investment, and buyers at values and terms favorable to the company. Certain industries and sectors experience waves of activity and interest. On the front end of these cycles, valuations and deal terms will likely favor the seller and can provide an opportunity for owners and management to act to monetize value closer to owner expectations. By the same token, a seller who holds out for more in a cold market might end up with no attractive options.

- The degree of process competition or engagement with multiple bidders. The presence of multiple, interested buyers or investors has a significant potential positive impact on the value for a seller or company raising capital and increases the likelihood of closing a transaction. Conversely, the buyer or investor who finds proprietary or unique targets and acts quickly can seize valuable opportunities. A well‐managed transaction process with the right teammates and advisors acting in one accord should prove to be an investment with a return and increase the likelihood of a successful outcome. For many business owners, selling a business or obtaining growth financing is like being on fourth and goal in the final quarter of the football game … there is no more critical time to execute and to execute well.

Preparing for and optimizing a business in anticipation of M&A and growth takes time and planning. In the public markets, shareholder value is paramount and often invoked as the deciding factor for doing deals. In private, middle market companies, price is important, along with the ambitions and motivations of its owners. The transaction process can be a significant distraction to a company; sufficient preparation that enables management to act both quickly and deliberately will have tangible value that should not be underestimated. Achieving shareholder objectives and the desired value requires a careful analysis and positioning in a way that can be done discreetly, with confidence, and on the shareholders' terms.

Formula Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Value | The enterprise value of the company is equal to the market value of the company's debt and equity |

| Expected cash flow | The future cash flow (normalized, after tax and after capital expenditures but before interest expense) that is expected to be generated by the business to service debt and then be available to shareholders |

| Cost of capital | Weighted average expected return for debt and equity based on the risk and capital structure of the business |

| Growth rate | The annual rate of growth of the expected cash flow |

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Operating profit | Normalized earnings before other income, other expenses, interest, and taxes |

| Adjusted taxes | Cash payments for corporate income taxes |

| Total assets | Total balance sheet assets using GAAP |

| Excess cash | Cash that exceeds the required amount as part of normal working capital |

| Marketable securities | Marketable securities that are not required as part of working capital or pledged to secure debt |

| Non‐interest‐bearing debt | Liabilities that are not subject to accrued or actual interest (which is funded debt). Typically this includes accounts payables and accruals. |

In both of these definitions, normalized refers to adjusting expenses and CAPEX to market values where specific items in the financial statements of the business skew the numbers solely for effect for the owners.

NOTES

- a. This chapter is partially adapted from the academic work by Kenneth H. Marks and John A. Howard and reprinted with permission: Kenneth H. Marks and John A. Howard, “Optimizing Private Middle‐Market Companies for M&A and Growth,” in Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions (vol. 14), edited by Gary L. Cooper and Sydney Finkelstein (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2015), pp. 67–82.

- b. There are variations and derivatives of this formula (called the Gordon Growth Model) that account for fast‐growth businesses and for those with negative short‐term cash flow and positive long‐term cash flow. We are using this simplified formula to provide context for the discussion, not implying that it is the actual formula for calculating a company's value.

- c. These levers effectively include many of the classically defined company‐specific risks used in the modified capital asset pricing model.

- 1. Tom Copeland, Tim Koller, and Jack Murrin, Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, 2nd ed. (John Wiley & Sons, 1996).

- 2. Michael Porter, “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, March 1979, https://hbr.org/1979/03/how-competitive-forces-shape-strategy.

- 3. Ken Sanginario, founder, Corporate Value Metrics, interview, December 2014.

- 4. Aswath Damodaran, Applied Corporate Finance (John Wiley & Sons, 1999).

- 5. Christian Blees, managing partner, BiggsKofford Capital, interview, December 2014.

- 6. Id.

- 7. Id.