SEMI-EFFICIENT MARKETS

The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable

world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest

kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite.

Life . . . looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is;

its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden;

its wildness lies in wait.

—G. K. CHESTERTON

I have a small army of former students who alert me to interesting stories I may have missed. One sent me a Wall Street Journal article titled “Clues Abound for the Small Investor to Divine Market Direction.” According to the article:

The long-term investor can make his decisions based on information easily available in his morning newspaper. Indeed, Thom Brown, managing director of the Philadelphia investment firm of Rutherford, Brown & Catherwood, advises investors to simply read a daily newspaper.

“Look for anything that suggests the direction of the economy,” he says. “Auto sales, for example, give you an idea about how willing consumers are to part with their money.” An expanding economy usually means rising stock prices.

Was this former student passing along a useful tip? Nope. She was contributing to my extensive collection of silly things said by sensible people. She added this note, “What everyone knows isn’t worth knowing.”

THE IDEA OF AN EFFICIENT MARKET

The efficient market hypothesis is that stock prices take into account all relevant information so that no investor can take advantage of other people’s ignorance. An efficient market does not require zero profits. After all, even boring bank accounts pay interest. Investors won’t buy stocks unless they expect to make some money. Stocks do pay dividends and the average stock investor does make money—about 10 percent a year over the past 100 years. The efficient market hypothesis is that no one can make excessive profits except by being lucky.

The stock market would not be efficient if sales of Ford F-150 pickup trucks jumped dramatically and investors who read about the sales increase in the morning newspaper could buy Ford stock at low prices from investors who didn’t know about the sales bump. Market efficiency does not assume that every investor knows about the sales increase—just that enough well-informed and well-financed investors are ready to jump-start Ford’s stock price to where it would be if everyone did know the news. Ford’s stock price should jump as soon as some investors know of the F-150 surge, and this immediate price bump protects amateurs from selling at outdated prices. An efficient market is a fair game in the sense that no investor can beat the market by knowing something other investors don’t know.

ANTICIPATED EVENTS AND SURPRISES

If a toy store’s sales increase before Christmas, will its stock price increase too? It depends. When the stock traded in the summer, investors tried to predict holiday sales and they valued the stock based on these predictions. If the forecasts turn out to be correct, there is no reason for the stock price to change on the day that the sales numbers are announced. The price will change, however, if sales turn out to be unexpectedly strong or disappointing.

Stock prices do not rise or fall when events that are expected to happen do happen. Stock prices do change if the unexpected happens. However, by definition, it is impossible to predict the unexpected. Therefore, it is impossible to predict changes in stock prices. That is a pretty good argument. So is its implication.

It is not enough to know that Ford F-150 sales increased last quarter or that auto sales increase when the economy gets stronger. The benchmark to gauge your investment ideas is not,

How is today different from yesterday?

or

How will tomorrow differ from today?

but

How does my prediction of tomorrow differ from what others expect?

When you think you have a good reason for buying a stock, ask yourself if you know something that other investors don’t know. If you do, it may be inside information that is illegal to use (for reasons discussed later in this chapter). If you don’t, your information is probably already reflected in market prices.

It seems obvious, but sometimes the obvious is overlooked. A longtime financial columnist for the New York Times offered this logical, but not very helpful, advice for buying bonds:

It is obviously good sense to buy bonds when the Federal Reserve Banks start lowering interest rates. It is just as obviously bad sense to buy them at any time when, two or three or four months hence, the Fed is certain to start raising money rates and lowering the prices of outstanding bonds.

Anything that has already happened or is certain to happen is surely already embedded in bond prices.

Similarly, you won’t get rich following this advice in the Consumers Digest Get Rich Investment Guide:

The ability to track interest rates as they pertain to bonds is made easier by following the path of the Prime Rate (the rate of interest charged by banks to their top clients). If the consensus shown in top business journals indicates that rates are going up, this means that bonds will go down in price. Therefore, when it seems that rates are moving up, an investor should wait until some “peaking” of rates is foreseen.

Seriously, isn’t it obvious that easily available information doesn’t give you an edge over other investors? What everybody knows isn’t worth knowing.

UNCERTAINTY AND DISAGREEMENT

The efficient market hypothesis does not assume that everyone agrees on what a security is worth. Market opinion of IBM in the spring of 1987 provides a particularly dramatic example. At that time, IBM was probably the most widely scrutinized company. Value Line’s highly regarded analysts gave IBM stock its lowest rating, placing it among the bottom 10 percent in predicted performance over the next twelve months. At the very same time, Kidder Peabody’s widely respected research department gave IBM its highest rating and included IBM in its recommended model portfolio of twenty stocks. This was not an isolated fluke.

On Thursday, November 11, 2010, TheStreet.com posted an article titled “How Nokia’s Stock Price Could Double.” Three days later, on Sunday, November 14, Seeking Alpha posted an article titled “Nokia Is Still Overvalued,” arguing that a “more realistic” value would be half of its current price. Nothing substantive happened between November 11 and November 14, yet these two influential websites had dramatically different views of Nokia stock. That’s why there are buyers and sellers.

For any stock, at the current market price, there are as many buyers as sellers—as many people who think that the stock is overpriced as think it is a bargain. The efficient market hypothesis says that it is never evident that a stock’s price is about to surge or collapse—for if it were, there wouldn’t be a balance between buyers and sellers.

The fact that changes in stock prices are hard to predict does not imply that stock prices are correct according to some external, objective criterion. Market prices reflect what buyers are willing to pay and sellers to accept, and both may be led astray by human emotions and misperceptions. This distinction is crucial for understanding what the efficient market hypothesis does and does not say.

MARKET TIMING

Most investors try to time their purchases and sales—to buy before prices go up and sell before they go down. A longtime financial writer for the New York Times offered this attractive goal:

Since we know stocks are going to fall as well as rise, we might as well get a little traffic out of them. A man who buys a stock at 10 and sells it at 20 makes 100 percent. But a man who buys it at 10, sells it at 14 1/2, buys it back at 12 and sells it at 18, buys it back at 15 and sells it at 20, makes 188 percent.

If only it were this easy!

It would be great to jump nimbly in and out of stocks, catching every rise and missing every drop, but how do we know in advance whether prices are headed up or down? J. P. Morgan was exactly right when he said that “the market will go up and it will go down, but not necessarily in that order.”

I am no fan of frenetic trading; still, there are times when stock prices are seriously out of whack because investors are far too pessimistic or optimistic. Our goal is to recognize compelling times to buy and times to sell. Ironically, the key is not to attempt to buy before prices go up and sell before they go down, but to think about whether the money machine is cheap or expensive—to be a value investor. I will explain this paradox in later chapters.

STOCK SELECTION

In contrast to market timing, stock selection is picking stocks that will beat other stocks, a task the efficient market hypothesis says is futile. For example, you might buy stock in a company that announces a large earnings increase and avoid firms that report flat or declining earnings. However, analysts predict earnings long before they are announced and stock prices reflect these predictions. Announcements that are in line with predictions—regardless of whether earnings are predicted to go up or down—have little effect on prices. To pick stocks that will do better than other stocks, based on their earnings, you need to predict which companies’ earnings surprises will be good news and which will be bad news. How does one predict surprises?

A former student told me about an interesting project he had worked on. His consulting firm had been hired by the directors of a major consumer-products company to recommend an executive compensation plan. The board wanted the firm, year after year, to be one of the highest-ranked consumer-products companies based on total shareholder return, dividends plus capital gains.

The consulting company immediately recognized the problem with this goal. Do you see it, too?

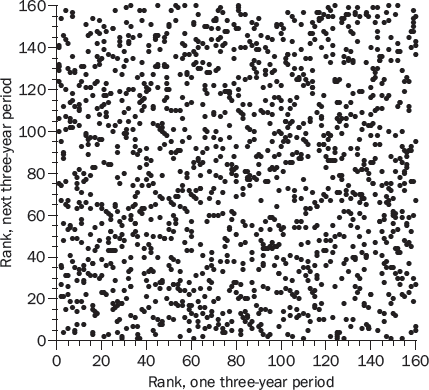

The consulting company calculated shareholder returns for 160 consumer-products companies over three-year intervals: 1980–1982, 1983–1985, and so on. For each three-year period, they ranked the companies from 1 to 160 based on total shareholder return. They then made a scatter plot with each firm’s ranking during one of those three-year periods on the horizontal axis and the ranking during the next three-year period on the vertical axis. The scatter plot in Figure 3-1 is striking, but not for the usual reason. Instead of showing a strong positive or negative correlation, it appears that a blindfolded person threw ink at paper.

That was exactly the point the consulting firm wanted to make. A company’s executives may be able to increase a firm’s profits, but trying to outperform the stock market year after year is an elusive goal. For a company’s stock price to go up more than investors expect, the firm must do better than investors expect. For the stock price to soar every year, the firm must do better than investors expect every year. Good luck with that!

THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONALS

Another way of testing the efficient market hypothesis is to look at the records of professional investors, who presumably base their decisions on publicly available information. If they consistently beat the market, they apparently have an advantage over amateur investors.

The record of professional investors as a group has been mediocre, at best. In his persuasive book The New Contrarian Investment Strategy, David Dreman looked at fifty-two surveys of stocks or stock portfolios recommended by professional investors. Forty of them underperformed the market. Perhaps some professionals are pros and the rest are amateurs pretending to be pros. Nope. There is no consistency in which professional investors do well and which do poorly. A study of 200 institutional stock portfolios found that of those who ranked in the top 25 percent in one five-year period, 26 percent ranked in the top 25 percent during the next five years, 48 percent ranked in the middle 50 percent, and 26 percent were in the bottom 25 percent.

CAN WE DISTINGUISH SKILL FROM LUCK?

Some investors do compile outstanding records. However, consider the coin-calling experiment that I sometimes do in my investment classes. Suppose that there are thirty-two students and that half of them predict heads for the first flip while half of them predict tails. The coin is flipped and lands heads, making the first half right. The sixteen students who were right then predict a second flip, with half saying heads and the other half tails. It comes up tails and the eight students who have been right twice in a row now try for a third time. Half predict heads and half tails, and the coin lands tails again. The four students who were right divide again on whether the next flip will be heads or tails. The result is tails and now we’re down to two students. One calls heads and the other tails. It is a heads and we have our winner—the student who correctly predicted five in a row. Are you confident that this student will call the next five flips correctly?

Even monkeys throwing darts and analysts flipping coins sometimes get lucky—an observation that cautions us that past successes are no guarantee of future success. Not only that, even if some analysts are somewhat better than average, stock market volatility makes it very difficult to separate the skilled from the lucky.

Imagine there are 10,000 analysts and 10 percent of them have a 0.60 probability of predicting correctly whether the stock market will go up or down in the coming year. The remaining 90 percent, like monkeys throwing darts, have only a 0.50 probability of making a correct prediction. Call the analysts in the first group skilled and those in the second group lucky.

If we look at their records over a ten-year period, we can expect six of the 1,000 skilled analysts to make correct predictions in all ten years. Among the 9,000 analysts who are merely lucky, nine can be expected to make ten correct predictions. This means that if we choose one of the fifteen analysts who have been right for ten years in a row, there is only a 40 percent chance that we will choose a skilled analyst. This is considerably better than the 10 percent chance of picking a skilled analyst if we ignore their records; but still—and this is the point—past performance is far from a guarantee of future success.

In practice, there is even more uncertainty because we often do not have a complete and accurate record over many years. Some analysts are too young. Others distort their records, perhaps by selectively reporting their successes and omitting their failures. Also, alas, skills are not constant. By the time someone has compiled an impressive track record, energy and insight may be fading.

Some investors surely are more skilled than lucky. However, the records of most are brief, mixed, or exaggerated, and there is no sure way to separate the talented from the lucky and the liars. The stock market is not all luck, but it is more luck than nervous investors want to hear or successful investors want to admit.

INSIDER TRADING

Section 10(b)5 of the 1934 Securities and Exchange Act makes it “unlawful for any person to employ any device, scheme or artifice to defraud or to engage in any act, practice or course of business which operates as a fraud or deceit upon any person.”

This law was enacted in response to a variety of fraudulent activities in the 1920s that manipulated stock prices and misled naive investors. For instance, an investment pool could push a stock’s price up, up, and up by trading the stock back and forth among members of the pool, and then sell to investors lured by the stock’s upward momentum.

Such activities have not disappeared completely. In 1987 a con man was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison after he pleaded guilty to conspiracy and fraud in manipulating the prices of two small stocks by buying and selling shares through fifty-three accounts at eighteen brokerage firms.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) also uses Section 10(b)5 for a very different purpose—to prosecute perceived insider-trading abuses. Insider information is not even mentioned, let alone defined in the law, but over the years, through a series of court cases, the SEC has created a set of legal precedents. The SEC has also gone after insider traders for related crimes, such as mail or wire fraud, obstruction of justice, and income tax evasion.

The SEC interprets illegal insider trading as that based on important information that has not yet been made public if the information was obtained wrongfully (such as by theft or bribery) or if the person has a fiduciary responsibility to keep the information confidential. Nor can investors trade on the basis of information that they know or have reason to know was obtained wrongfully.

The SEC is unlikely to press charges if it is convinced that a leak of confidential information was inadvertent; for example, a conversation overheard on an airplane. However, courts have consistently ruled that a company’s officers and directors should not profit from buying or selling stock before the public announcement of important corporate news. The SEC has also won cases against relatives and friends of corporate insiders, establishing the principle that someone tipped by an insider is an insider, too. In the 1968 Texas Gulf Sulphur case, involving the purchase of stock by company executives and outsiders who had been tipped before the public announcement of an enormous ore discovery, a federal appeals court ruled that “anyone—corporate insider or not—who regularly receives material non-public information may not use that information to trade in securities without incurring an affirmative duty to disclose.”

The SEC has frequently won cases based on a different principle—that insider trading is robbery, the theft of information. In 1984, a federal court of appeals upheld the conviction of Anthony Materia, a printing house employee, who had decoded documents (with missing company names) that he was printing relating to mergers and takeovers and then bought shares in the target companies. The court ruled that he violated a duty to his employer and its clients when he “stole information to which he was privy in his work. . . . Materia’s theft of information was indeed as fraudulent as if he had converted corporate funds for his personal benefit.”

Please don’t take chances cheating and hoping to outwit the SEC. It isn’t worth it and you don’t need to break any laws. You can make more than enough money by being an honest value investor.

HUMAN EMOTIONS

Investment decisions depend not only on known facts, but also human emotions like greed and overconfidence, which lead some investors astray and leave opportunities for others. This is why the stock market is only semi-efficient. Here are three examples.

Confusing a great company with a great stock. We eat in a good restaurant, buy a fun toy, admire attractive clothing, see a wonderful movie, ride in a nice car, and think, “I should buy stock in that company.” Before rushing to buy, ask yourself whether you are the only one who knows how wonderful these things are. If not, the stock price probably already reflects the fact that it is a good company. The question is not whether the products are worth buying, but whether the stock is worth buying. If the stock’s price is too high, the answer is no.

Later, you will see that the glamour stocks of companies that make great products and generate strong profits are more likely to be overpriced than are the stocks of struggling companies. Who has the courage to buy stock in bad companies? Not many, which is why struggling companies’ stocks are often cheap.

Buying hot tips. My family went on a vacation to Costa Rica in 2010 and we met a man named David who bragged that he was paying for his vacation with the profits he was going to make on a stock investment. I asked him about the stock and was not surprised when he said that he had been given a hot tip by his auto mechanic on a stock that had nothing whatsoever to do with cars.

The hot tip was Ecosphere Technologies (ESPH), a small company that owns several environmental technologies, including the Ecos PowerCube, a solar-power generator that can be used in remote locations. David bought 10,000 shares at $1 per share in early March. The price had jumped to $1.65 in late March and his $6,500 profit was enough to pay for his Costa Rica vacation.

The problem was that, year after year, Ecosphere Technologies either lost money or made a small profit. There was nothing to prop up the price except people like David, who were buying the stock based on a hot tip. Figures 3-2 and 3-3 show that there was a huge surge in the stock’s price and the volume of trading during the first three months of 2010 (when David bought). Then the price collapsed. Six years later, the price was 3 cents a share.

ESPH’s stock price had gone up, no doubt fueled by people who heard the hot tips and rushed to buy the stock. There are two problems with hot tips. One is that they may be unfounded rumors, perhaps spread by people who own the stock already and want to sell at a higher price. Second, if there is any truth to the rumors, it may already be embedded in the price.

Chasing trends. I was talking to a friendly guy named Lou at a party and he told me that, because he lives in California, he gets up at five thirty every morning so that he can be at his computer, ready to trade, when the stock market opens at six thirty Pacific Time. He has a software program that alerts him when it notices a stock price going up by some preset amount; for example, one percent since the market opened or one percent in the past hour. Lou watches the price for a few moments and, if he likes what he sees, he buys the stock and holds it until the price goes down enough to persuade him that the run-up is over.

I asked Lou how he was doing and was surprised by his candor: “I lower my tax bill every April.” He explained that, on balance, he always seems to have more capital losses than gains and he can use his net capital losses to reduce his taxable income. He said that he is still trying to perfect his timing but, more often than not, he either buys the stock too late (after the run-up is over) or sells too late (after he has lost money).

Lou’s explanation is just a roundabout way of saying that chasing trends doesn’t work because what a stock price has done in the past is an unreliable predictor of what the price will do in the future.

Sometimes, there are a lot of folks like Lou out there, chasing the same trends. They notice stock prices going up (perhaps because their friends are bragging about how much money they are making) and rush to buy so that they can make money, too. When lots of trend chasers are buying, their lust can push prices higher still, luring more trend chasers. This imitative behavior fuels speculative bubbles—stock prices going up for no reason other than people are buying stock because prices have been going up.

When stock prices stop going up, they go down very fast because there is no reason to buy other than a belief that prices will go up.

THE DELUSION OF CROWDS

Michael C. Jensen, a Harvard Business School professor, wrote, “The vast scientific evidence on the theory of efficient markets indicates that, in the absence of inside information, a security’s market price represents the best available estimate of its true value.” The idea is that while some investors may substantially overestimate the value of a stock, other investors will err in the other direction, and these errors will balance out so that the collective judgment of the crowd is close to the correct value.

The wisdom of crowds has a lot of appeal. The classic example is a jelly bean experiment conducted by finance professor Jack Treynor. He showed fifty-six students a jar containing 850 jelly beans and asked them to write down how many beans they thought were in the jar. The average guess was 871, an error of only 2 percent. Only one student did better. This experiment has been cited over and over as evidence that the average opinion of the value of a stock is likely to be close to the “correct” value.

The analogy is not apt. As Treynor noted, the student guesses were made independently and had no systematic bias. When these assumptions are true, the average guess will, on average, be closer to the true value than the majority of the individual guesses. That is a mathematical fact. But it is not a fact if those assumptions are wrong. After the initial student guesses were recorded, Treynor advised the students that they should allow for air space at the top of the bean jar and that the plastic jar’s exterior was thinner than a glass jar. The average estimate increased to 979.2, an error of 15 percent. The many were no longer smarter than the few. “Although the cautions weren’t intended to be misleading,” Treynor wrote, “they seem to have caused some shared error to creep into the estimates.”

There is a lot of shared error in the stock market. Investor opinions are not formed independently and are not free of systematic biases. Stock prices are buffeted by fads, fancies, greed, and gloom—what Keynes called “animal spirits.” Contagious mass psychology causes not only pricing errors, but speculative bubbles and unwarranted panics.

In an investor survey near the peak of the dot-com bubble in 2000, the median prediction of the annual return on stocks over the next ten years was 15 percent. It wasn’t just naive amateurs. Supposedly sophisticated hedge funds were buying dot-com stocks just as feverishly as small investors. This was not collective wisdom; this was collective delusion. They didn’t see the bubble because they did not want to see it. The actual annual return over the next ten years turned out to be -0.5 percent.

The 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics was given to two economists with very different views of the efficient market hypothesis. As described by Chicago professor Eugene Fama:

An “efficient” market for securities . . . [is] a market where, given the available information, actual prices at every point in time represent very good estimates of intrinsic values.

Yale professor Robert Shiller has a very different view:

One form of this argument claims that . . . the real price of stocks is close to the intrinsic value. . . . This argument for the efficient markets hypothesis represents one of the most remarkable errors in the history of economic thought.

Fama believes that markets set the correct price, the price that God herself would set, and that changes in stock prices are hard to predict because they are caused by new information, which, by definition, cannot be predicted.

Shiller’s view is that changes in stock prices may be hard to predict because of unpredictable, sometimes irrational, revisions in investor expectations—as if God determined stock prices by flipping a coin. If so, changes in market prices are impossible to predict, but market prices are not good estimates of intrinsic value.

What they both agree on is that it is hard to predict changes in stock prices. It is tempting to think that, as in any profession, good training, hard work, and a skilled mind will yield superior results. And it is especially tempting to think that you possess these very characteristics.

A student did a term paper in my statistics class at Pomona College where 200 randomly selected students were asked if their height, intelligence, and attractiveness were above average or below average compared to other Pomona students of the same gender. The reality is that an equal number are above average and below average. Individual perceptions were quite different. Fifty-six percent of the female students and 49 percent of the males believed their height was above average, well within the range of sampling error. However, 84 percent of the females and 79 percent of the males believed their intelligence was above average; and 74 percent of the females and 68 percent of the males believed their attractiveness was above average.

It is a common human trait, probably inherited from our distant ancestors, to overestimate ourselves. Back then, it was hard to survive in a challenging, often unforgiving world without confidence. Self-confidence had survival and reproductive value and came to dominate the gene pool. These days, we still latch on to evidence of our strengths and discount evidence to the contrary. This is so common that it even has a name: confirmation bias.

We think we can predict the result of a football game, an election, or a stock pick. If our prediction turns out to be correct, this confirms how smart we are. If our prediction does not come true, it was just bad luck—poor officiating, low voter turnout, the irrationality of other investors.

Very few investors think they are below average, even though half are. After all, would people sell one stock and buy another if they thought they would be wrong more often than right? Every decision that works out confirms our wisdom. Every mistake is attributed to bad luck beyond our control.

This overconfidence is why people trade so much, thinking they know more than the investors on the other side of their trades. It is why investors don’t hold sufficiently diversified portfolios, believing that there is little chance that the stocks they pick will do poorly. It is why investors hold on to their losers, believing that it is only a matter of time until other investors realize how great these stocks are.

WARREN BUFFETT AND SOME CONTRARIANS

Human sentiments like greed and overconfidence illustrate the crucial difference between possessing information and processing information. Possessing information is knowing something about a company that others do not know. Processing information is thinking more clearly about things we all know.

Warren Buffett did not beat the market for decades by having access to information that was not available to others, but by thinking more clearly about information available to everyone. Beginning in 1956 with a $100,000 partnership, he earned a 31 percent compound annual rate of return over the next fourteen years, with never a losing year. In 1969, feeling stocks to be overpriced, Buffett left the stock market and dissolved the partnership. The “wizard of Omaha” returned to the stock market in the 1970s, making investments through Berkshire Hathaway, formerly a cloth-milling company. Continuing to earn nearly 20 percent a year, his net worth was $65 billion in 2016.

In the 1980s I debated the efficient market hypothesis with a prominent Stanford professor. I said that Buffett was evidence that the market could be beaten by processing information better than other investors. His response was immediate and dismissive: “Enough monkeys hitting enough keys . . .” He was referring to the classic infinite monkey theorem, one version of which states that a handful of monkeys pounding away at typewriters will eventually write every book that humans have ever written. One eternal monkey could do the same; but a very large number of monkeys could be expected to do it sooner. The Stanford professor’s argument was that with so many people buying and selling stocks over so many decades, one person is bound to be so much luckier than the rest as to appear to be a genius—when he is really just a lucky monkey.

In a 1984 speech at Columbia University celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd’s value-investing treatise, Security Analysis, Buffett rebutted the lucky-monkey argument by noting that he personally knows eight other portfolio managers who, like Buffett, adhere to the value-investing principles taught by Graham and Dodd. All nine have outperformed the market dramatically for many years. How many monkeys would it take to generate that performance?

Yet many academics are skeptical (or perhaps jealous?). In 2006, Austan Goolsbee, a Chicago Booth School of Business professor who served as chair of the Council of Economic Advisers for President Obama, was interviewed on American Public Media and said:

I’d tell [Berkshire Hathaway] shareholders to watch their wallets. See, I’m an economist, and it always sticks in my craw when people say Warren has the Midas touch. That’s because the one thing that professors pound into young economists is that the only investors who beat the market are ones who get lucky or else take risk.

I am unpersuaded. I have a personal interest in believing that some investors process information better than others, just as some doctors and lawyers do. My belief in Buffett is fortified by the fact that, unlike monkeys, Buffett makes sense. His annual reports are exceptionally wise and well written. They are also his own opinions, not a repackaging of what others are saying.

Too many investors are hostage to a groupthink mentality that values conformity above independent thought. Ironically, institutional groupthink is encouraged by a legal need to be “prudent.” Just as no purchasing agent ever got fired for buying IBM equipment, so no money manager has ever been thought imprudent for buying IBM stock. As Keynes observed, “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” Who can fault someone who fails when everyone else is failing?

Buffett generally ignores the crowd and makes up his own mind. Other investors have prospered by watching the crowd and doing the opposite. In May 1932, with stock prices at their lowest level in this century, Dean Witter sent a memo to his company’s brokers and management saying:

All of our customers with money must someday put it to work—into some revenue-producing investment. Why not invest it now, when securities are cheap?

Some people say they want to wait for a clearer view of the future. But when the future is again clear, the present bargains will have vanished. In fact, does anyone think that today’s prices will prevail once full confidence has been restored?

That’s exactly right. Bargains are not going to be found when investors are optimistic, but when they are pessimistic. In Warren Buffett’s memorable words, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

If the herdlike instincts of institutional investors push the prices of glamour stocks to unjustifiable levels, then perhaps the road to investment success is to do the opposite—as J. Paul Getty advised in his autobiography, “Buy when everyone else is selling and hold until everyone else is buying.” A deliberate attempt to do the opposite of what others are doing is called a contrarian strategy, and it can be applied to individual stocks (buying the least popular stocks) and to the market as a whole (buying when other investors are bearish).

The experts have been notoriously wrong at dramatic market turning points: In recent years, they were optimistic before the dotcom bubble popped in the spring of 2000 and pessimistic before the market bottomed in the summer of 2002. The optimism returned as the market peaked in the summer of 2007, followed by pessimism as the market bottomed in the winter of 2009.

With individual stocks, the favorites often do poorly. A representative example is a study of the recommendations of the twenty “superstar” analysts selected in a poll of institutional investors. Of the 132 stocks they recommended, two-thirds did worse than the S&P 500. The average gain for the 132 stocks picked by the most respected and highly paid security analysts was 9 percent, as compared to 14 percent for the S&P 500. A large institutional buyer of research concluded glumly, “It’s uncanny—when they say one thing, start doing the opposite. Usually you are right.”

These superstar pros were not throwing darts. They were infatuated with fads, overconfident of their abilities, chasing trends, or seduced by other human misperceptions.

Because of these human emotions, the stock market is only semi-efficient, which is good news for value investors—who don’t throw darts, either.