Chapter 4

It’s Not Just You— Manage Your Worry

In This Chapter

- change distribution model

- stress and worry about change

- your worry log index exercise

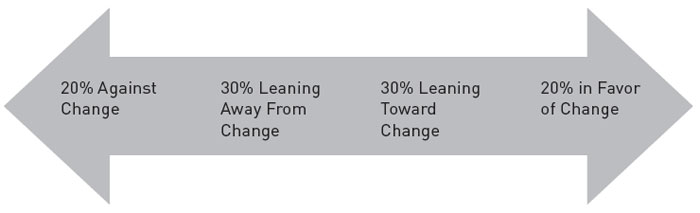

How well do you believe this statement describes how most people feel about organizational change? “I’m all for change as long as it doesn’t affect me!” Accurate, don’t you think? It’s a well-demonstrated dynamic of the human condition that we will do almost anything to avoid facing difficult, stressful, or fearful situations. The following graphic demonstrates how those individuals on the front line facing change (the change intended group as identified in chapter 2) react to organizational change.

Figure 4.1. Change Intended’s Reaction to Change

Change Distribution Model

In the model above, you see that 20 percent of those who are faced with change will resist it. These individuals see themselves as victims of the change. On the opposite end of the spectrum are the 20 percent who are totally in favor of change and welcome it from the very beginning. They are the most likely to remain successful in the organization as the changes are introduced and implemented. In the middle are those who survive and will accept change but only under certain conditions. About 30 percent of these people will be leaning toward accepting change, and about 30 percent will be leaning away from accepting change. Often it’s not until the results of the change are known that those in the middle categories commit themselves. This is not to say that only 20 percent of the change intended will completely embrace change. This is simply how the change intended react under most circumstances. The good news is that we all have the ability to choose how we will react and adapt to change. Here are some example change stories to consider.

Radical Change in a 75-Year-Old Company

The reorganization in the ABC Company represented the most radical changes ever made in the company’s 75-year history. Several entirely new functions were created, which meant new reporting relationships in the organization. Although some people thought they were passed over for certain opportunities, the initial feeling about the reorganization was generally positive. The changes were implemented to create a more streamlined organization— one that could meet the increasing demands of customers and respond more quickly to their needs. It all sounded great on paper. And if the changes had been implemented more effectively, the results might have been more in line with what was intended.

Information about the changes was kept secret and only those with an absolute need to know were included in what was planned; even these insiders felt they were left mostly in the dark. This secrecy had the unintended effect of creating more anxiety about the future. Worse yet, those whose responsibilities were going to be most affected were not informed of their new jobs until immediately before the reorganization’s announcement. Some managers were not even told about the reorganization in advance and instead heard about the changes in their jobs for the first time via an email sent to everyone on the company’s intranet.

Once these changes were announced and new positions were created, there was still much confusion about everyone’s new roles. Resentment was common among the employees. Instead of creating a more efficient organization, the reorganization resulted in a more fragmented and misdirected workforce, and the organization struggled to reach its intended goals. Soon those undecided change intended (leaning both for and against the change) began to reassess their middle ground positions and began to move toward feelings of victimization.

A New Performance Initiative

XYZ Company decided that a new award program would improve their lagging market performance. The employees were never told the criteria for qualifying for an award, however, just that they would receive one if certain performance targets were met. Instead of working to meet goals for improved performance, they had no choice but to continue doing their jobs as they always had done in the past.

Disappointed with their new program’s failure to improve the company’s performance, the initiators canceled the award program in its first year. As a result, this award initiative caused confusion and mistrust throughout the organization—rather than creating a motivated workforce striving to achieve more challenging team goals in order to remain competitive in the marketplace.

Common Problems

These two stories represent common problems when large-scale change initiatives are introduced (as in the case of ABC Company) or more specific performance improvement initiatives are introduced (as in the case of XYZ Company). Often, the design of performance improvement initiatives is the issue; they are presented in the form of challenges to the workforce without providing the support systems necessary to accomplish their goals. For example, if an organization wants to improve safety performance, it might measure the number of injuries reported in a given period of time (monthly, yearly). It might then provide incentives to lower the injury frequency rate—such as shirts, jackets, caps with safety insignias, or even cash bonuses for reaching certain goals. But these incentives may result in an unintended consequence: a reduction in the number of accidents reported rather than everyone working more safely.

Stress and Worry About Change

Stress and worry are some of the natural consequences of change and are partly why those involved in it hope change happens to someone else first. But deflecting or compartmentalizing the anxiety and worry only lasts so long. Eventually, as the saying goes, “the rooster comes home to roost.”

Most of all, change causes us to worry. We worry about whether we’ll still have a job in the future. We worry about having to learn new skills. We worry about moving to another location or another department. Whether the move is to the adjoining desk or across the country, there’s bound to be stress and worry. Regardless of how the move affects you, you cannot escape a certain amount of anxiety about the change.

However, the one fact often overlooked as worry sets in is that most of what we worry about never really happens. Often it is the possibility of things happening that causes us more stress and worry than the actual event. Many change initiators make the mistake of dragging out the announcement and implementation of a change. Nothing is worse for the change intended. The longer questions go unanswered, the more ominous the perceptions are about the pending change. It’s the anticipation and fear of the unknown that are usually the worst part of the entire change process. And the rumor mill doesn’t help.

Tools, Techniques, and Exercises

Tools, Techniques, and Exercises

Everyone tells us not to worry, but that is generally a tall order during stressful events such as organizational change. The following tools, techniques, and exercises will help you manage your own levels of stress and worry.

Worry Index Exercise

The following index is designed to help you better understand how much time you spend worrying about things related to change in your life and the results of all this worry. Circle the frequency indicator for each of the questions that follow.

| 1. | Approximately how much do you worry each day about change at work? |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Less than 1 hour | 2-3 hours | 4 hours | 5-6 hours | 8 or more hours |

| 2. | How much of an effect does this worry have on your job performance? |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Considerably | Very Strongly |

| 3. | How does your concern about changes at work affect your home life? |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Considerably | Very Strongly |

| 4. | How does worry about changes at work affect your overall physical health? |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Considerably | Very Strongly |

| 5. | When you stop and really think about it, how much of what you worry about actually happens? |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Never | Seldom | Often | Sometimes | Frequently |

Interpreting Your Worry Index

Add up the numbers corresponding to your answers in the Worry Index. If you scored 15 or less, you worry about an average amount (and your worrying is nothing to worry about). A score of 15 to 24 indicates you are probably worrying much more than you should. If you scored 25, you need to explore what is causing you so much worry—and what you can do to address these concerns about changes that are occurring in your work life.

- Do you think you spend too much time worrying about things that never actually happen? Explain.

- How productive is your worrying?

- How counterproductive is it?

Your Worry Log Exercise

It may be helpful for you to complete this Worry Log during your next week at work. The Worry Log is designed to help you see how much of what you worry about actually comes true.

In column 1, simply record something you are currently worried about happening during the next week. In column 2, record the outcomes after the week has passed. In column 3, indicate how legitimate your worries were by indicating whether they became a reality or not. In column 4, calculate what percentage of your worries actually comes true.

Table 4.1. Worry Log

| Your worries at the beginning of the week | Actual outcomes of these worries. (Complete after week is over.) | Did this worry become reality? Yes or No | % of worries that came true |

What’s Next?

So now you’re in charge of worrying about coming change. The next chapter provides some help on adjusting your attitude to fully participate in and be successful during change.