5

A strategic approach to adopt ICT: from using information and communication technology to making use of information and technology to communicate

Abstract

This chapter presents the strategic perspective followed in fields such as information systems that can help MIPs to better analyse and understand their needs and to decide with a greater degree of success which ICT they should integrate into their practice. As the title reads, it is not a matter of how much ICT is used, but a matter of using the most suitable one to address the needs of each organisation.

Keywords

information systems

strategy

IS strategy

levels of management

ICT adoption

IS adoption

levels of adoption

This chapter focuses on discussing how an information systems approach can help MIPs make a strategic use of ICT to achieve their business goals and be productive while optimising efficiency and effectiveness. First, an introduction to a strategic approach is presented, then the concept of information systems strategy and what it involves is defined, and finally a review of relevant literature from the bodies of small business management and information systems research is presented to provide a solid basis that can be used to better understand IS and ICT adoption in the setting up of translation businesses.

5.1. The Information Systems approach to ICT

As explained in Chapter 2, the information systems of an organisation consist of the information technology infrastructure, data, application systems and personnel that employ ICT to deliver information and communications services in an organisation, but it also refers to the management of the organisational function in charge of planning, designing, developing, implementing and operating the systems and providing services (Davis, 2000). Thus, the concept of IS combines both the technical components and the human activities within an organisation and describes the process of managing the life cycle of organisational practices. The main goal of information systems is to gain a competitive advantage through efficient and effective use of the human and technology resources of an organisation and multilingual information professionals, either as freelancers or as part of small or micro businesses. These businesses are in great need of getting things done right in their day-to-day activities (i.e. being efficient) and of doing the right thing to provide quality solutions that meet the requirements of the market (i.e. optimising their effectiveness to gain a competitive advantage). Information systems have already been going down this path for a long time; however, MIPs still have a long way to go in this sense.

It is not a matter of how many tools you might master or how many resources you might gather and have within your reach; it is not a matter of how much you know about a particular domain of knowledge or how much you invest in training or acquiring the latest technology. It is about how well you are capable of deciding which are the best tools or technology you need for your particular working setting; it is about being capable of organising your resources effectively to retrieve the very particular piece of information you need in the shortest time to remain productive and deliver a consistent and quality service; it is about being capable of recognising your information needs at every moment and learning to evolve and adapt your business to the changes and new developments; and it is about developing a knowledge-based system that is tailored to your business needs and that involves all the human and material resources that are part of your working setting. All in all, it is about adopting a strategic view that is aimed at being aware of your working setting and making the right decisions to be efficient and effective.

It is clear that IS were created to address the needs of large, complex organisations, with large scale and scope IS, and best fit this type of organisation. It might seem that a much simpler organisation, such as an SME or a micro business, is in no such need to use heavy-duty decision-making machinery, but still there are many advantages that can be adapted to the particular context of smaller organisations to successfully undertake an information-related activity (Yap et al., 1992; Thong, 1999; Tapscott, 2004). Given the characteristics of MIPs’ business, and that this type of activity deals intensively with information and knowledge, it makes them likely candidates to benefit from IS.

Given the lack of formal approaches to address the organisational complexity of translation businesses and the lack of formal frameworks to drive ICT-related decisions and processes in this setting, the lessons learned from the field of business strategy and information systems can provide a useful reference to underpin an IS strategy for MIPs and to reach the strategic fit that enables productivity and quality services. A freelance business requires a much simplified architecture than a large organisation, which on one hand reduces the number of functions and systems to be coordinated, but on the other concentrates the different functions of the business into one person, i.e. the manager, thus increasing the volume of managerial and administrative tasks that affect the core activity and the degree of dependence on this person.

IS are aimed at empowering managers, engineers, and ICT users with knowledge and techniques for effective decision making. In the case of multilingual information professional practice in a freelance context, the same person needs to assume all these roles in with a greater or lesser level of intensity, depending on the type of projects undertaken. It is clear that the theory and logic for managing an organisation involves a considerably more complex scheme than in the case of micro SMEs like freelancers. It is also clear that information systems support the objectives of organisations and their rationality by providing support to analytical processes. Then, why should freelancers design an information system aimed at formalising the use of ICT and the management of the business? Why even just think about an ideal framework if their (micro) organisation is much simpler? The reason is that, even though organisations never function according to the ideal – neither do the large ones (Davis, 2000, p. 65) – using information systems adds coherence to deploying ICT and to decision making.

Therefore, an IS strategy approach can help MIPs to apply ICT appropriately in a timely way and in harmony with their business strategies, goals and needs.

5.2. Information Systems strategy

IS strategy is a complex concept which includes three streams of literature (Chen et al., 2010): strategic information systems planning (SISP) (Galliers, 1991; Premkumar and King, 1994; Peppard and Ward, 2004), alignment between IS strategy and business strategy (Henderson and Venkatraman, 1993; Chan et al., 1997; Chan and Reich, 2007), and competitive use of IS or using IS for competitive advantage (Melville et al., 2004; Wade and Hulland, 2004; Piccoli and Ives, 2005).

Chen et al. define IS strategy as “an organizational perspective on the investment in, deployment, use, and management of information systems” (2010, p. 235) in their comprehensive review and analysis of this concept and differentiate three conceptions of IS Strategy (2010, p. 238), namely, “(1) IS strategy as the use of IS to support business strategy; (2) IS strategy as the master plan of the IS function; and (3) IS strategy as the shared view of the IS role within the organization.”

In the particular context of multilingual information professionals, the first conception, IS strategy as the use of IS to support business strategy, assumes that a particular business strategy is already guiding the professional activity, which does not usually seem to be the case for translators, or at least a formally defined one (Granell-Zafra, 2006, p. 215). Still, if this strategic view is to be adapted to this setting it is important to outline the objectives pursued by the translation business in the short, medium and long term and make them explicit to better assess how an IS strategy can help gaining or sustaining the targeted competitive advantage. This is usually called “alignment” or “fit” between the business strategy and the IS strategy, and, although not in managerial terms, it has also been acknowledged in the translation sector by authors like King, who outlines as a critical factor the need for a preliminary analysis before adopting translation tools and states that “maximum benefit from introducing translation technology can be gained by careful preliminary analysis of what is really needed and of the consequences of introducing it” (King, 1998). This strategic approach to define the IS strategy of a MIP’s business helps focus on core customers to improve effectiveness, defining a suitable organisational structure that is aligned with the objective of the business, and having a long-term thinking capable of achieving future goals.

Chen et al.’s second conception of IS strategy, i.e. IS strategy as the master plan of the IS function, is more specific to the IS function within the business and focuses on defining the particular IS assets (information needs, hardware, software, communications, data, people, training) required to reach the desired level of efficiency as well as on planning how to structure them to best accomplish day-to-day operations. It can be applied to organisations that do not have a clear business strategy or that look for functionality over gaining a competitive advantage (Duncan, 1995; Byrd and Turner, 2001; Bhatt et al., 2005). This tactical approach to defining the IS strategy of a MIP’s business can enhance the visibility of the work processes and practices to ensure that work is being done towards fulfilling the objectives of the business (i.e. to clearly know why and how things are being done) and to improve operational and communicative practices dynamically to adapt the business to possible changes in the environment.

The third conception of IS strategy, i.e. IS strategy as the shared view of the IS role within the organisation, has to do with the overall perspective towards IS. It is necessary, from a strategic point of view, to share a common vision across the organisation that guides any ICT or training investments, as well as deployment decisions. In the context of MIPs’ businesses, which might not involve many people, it is still very important to position the identity of the organisation from a cultural, technological, social and business viewpoint. This can not only be helpful in guiding any innovations and investments internally, but also in engaging colleagues and collaborators, and in involving customers and providers into the culture of the business services provided.

IS are not only developed because organisations (or their managers) want to do things faster or because they want to have the latest and greatest technology. IS are developed strategically to help gain or sustain some competitive advantage over rivals (Porter and Millar, 1985). Although the approach followed in this book is that of a broader conception of an IS (i.e. that involving the three conceptions of IS strategy detailed above), some scholars differentiate functional IS from those IS particularly aimed at gaining a competitive advantage, called “Strategic IS.”

Porter (1979; 2008) identifies five competitive forces that operate in a business environment and that can help each organisation to better address the risks posed by its market:

• the threat of new entrants;

• the bargaining power of suppliers;

• the bargaining power of customers;

• the threat of substitute products or services;

• the rivalry among existing competitors.

Technology use can be a powerful enabler of competitive advantage and for achieving innovative ways of developing multilingual communication effectively, thus differentiating the services provided by MIPs from the crowd of professionals competing in the global market. Therefore, IS, in addition to the IL perspective discussed in Chapter 4, can be a valuable help towards an informed approach for adopting ICT. The next section of the chapter is focused on addressing these aspects.

In summary, the objective of the IS strategy should then be aimed at defining the structure within which information, information systems and information and communication technology is to be applied within the organisation over time. An IS requires the specification of the information needs; the processes necessary to collect, produce, store and disseminate information; the systems needed to support the organisational activity in these processes; the hardware, software, communications and data facilities required; the people involved in the processes; and the competences needed to support the information systems. In order to achieve a successful IS strategy, planning is required to develop all the aspects around the strategy, to define how they should be structured, and to establish short, medium and long-term objectives and infrastructure that will allow information systems to be designed and implemented efficiently and effectively.

5.3. IS and ICT adoption in small businesses

Trying to strategically address the adoption of IS and ICT is not an easy task. Nevertheless, although CAT tool adoption has not been much researched in the translation sector, there are other areas in which research about the adoption of technologies in small businesses has been studied more extensively, mostly in the last two decades of the 20th century. This section presents a discussion of the seminal literature identified in the domains of Information Systems (IS) and small business management.

Within each of these domains, a number of more specific areas were deemed important to the present research, namely,

• Small business management:

• IS/ICT adoption strategies in small businesses;

• IS/ICT adoption factors in small businesses, including motivators and inhibitors;

• the influence and role of the CEO in IS/ICT adoption decisions.

• Information systems:

• measures for determining the success of IS/ICT adoption and implementation in organisations;

• stage models of IS/ICT adoption in organisations.

5.3.1. ICT and SMEs

The dawn of the 21st century was marked by an information-based economy that made organisations more reliant upon Information and Communication Technology and Information Systems to support their business processes (Irani and Love, 2001a). However, research undertaken by Kempis and Ringbeck, (1999) claims that a higher availability of ICT does not always translate into higher efficiency and effectiveness, and suggests that a significant proportion of organisations may be under-performing with regard to efficiency and effectiveness of ICT utilisation. Researchers and practitioners are seeking an explanation for this fact. For example, McKay and Marshall (2001) state that the notion of an information-based economy and the arrival of an e-business domain have led to considerable faith being placed in IT to deliver performance improvements, and that there is a concern that ICT/IS is not delivering what it promises. Irani and Love (2001a; 2001b) attribute this lack of delivery to the difficulty in determining business value from ICT/IS investments, and the considerable indirect costs associated with enterprise-wide systems. The measurement of business value of ICT/IS investments has been widely debated in the IS and business management literature (see, for example, Weill and Olson, 1989; Serafeimidis and Smithson, 1996; Irani et al., 2001), yet there has been a lack of consensus in defining and measuring ICT/IS investments (Irani and Love, 2002). This area of research has looked at these issues in the broad organisational context, but it represents a more critical problem in the case of the SMEs, where management functions and ICT budgets are more limited.

In SMEs, managers play a decisive role when deciding about investing in new technologies (Cragg and King, 1993), therefore, they have to carefully consider the potential impacts of acquiring them, and then take an informed decision of the investment. In order to better utilise resources, managers need to have an understanding of the impact of ICT/IS on the organisational infrastructure and overall performance, as shown in the discussion of ICT/IS evaluation above. This literature shows that an analysis of potential impacts of ICT/IS for SMEs is needed, and once an ICT/IS has been adopted, ICT/IS evaluation would provide feedback that allows to better establish benchmarks of what is to be achieved by ICT/IS investments.

Studies on the evolution of IS in SMEs (see, for example, Saarinen, 1989; Cragg and Zinatelli, 1995) have identified several approaches to investigate the evolution of IS in organisations, although not necessarily small firms. First, a number of models have looked at the growth stages undergone by organisations adopting ICT/IS. Second, a number of factors that influence the decision of adopting ICT/IS in SMEs have also been studied to understand what are the determinants of the adoption. Other studies have looked at the factors that determine the IS success. Finally, IS evolution has also been studied through the concept of its sophistication in organisations. These four aspects of the IS literature on ICT adoption in SMEs are analysed in the following sections and related to the specific case of freelance translation businesses.

5.3.2. Models of ICT adoption in SMEs

According to Cragg and Zinatelli (1995), one of the related areas identified by researchers as relevant to understand the adoption of new ICT is the analysis of “stage models” of IS adoption and evolution in organisations, which are based on the assumption that computing moves through a series of growth stages.

Saarinen (1989) reviewed the existing literature about the evolution of an organisation’s information systems through the discussion of models developed in IS science and the broader theoretical features to which they apply. This review goes from, according to King and Kraemer (1984), the important initial step in research into the evolution of IS in organisations (Churchill et al., 1969; Nolan, 1973; Nolan, 1979) to more specific-area models (IBM, 1981; McFarlan et al., 1983; Rockart, 1983; Zmud et al., 1987). The early stages of growth in these models seem to be close to each other in the models, but as the growth process proceeds, more differences in the assumed development patterns can be detected. According to Saarinen, these models explicitly or implicitly incorporate underlying theoretical principles from economics, diffusion theory, organisational learning, and growth and stages theory.

Economic theories offer a whole body of literature which could be applied in analysing the development of computing in organisations, and Saarinen cites Schumpeter (1934) as an example. These theories assume that the balance between supply and demand for ICT is reached in the same way as in the market (i.e. the price of using ICT determines the demand). However, researchers of ICT/IS evolution have considered that economic theories did not provide an answer to ICT/IS evolution, which changes over time, and that other, more descriptive, models and theories were needed to explain the mechanisms beyond the adjustment process of demand and supply (Saarinen, 1989, p. 393).

Diffusion theories define “diffusion” as “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system” (Rogers, 1995, p. 5). Saarinen (1989, p. 393) states that “diffusion theories could offer a wide and well-formulated set of models […] meant for use in studying a phenomenon which represents one possible view of the development of computing in organisations,” and that “authors in the IS field seem to have been aware of this literature, but the existing diffusion models have not been used significantly until now.”

Organisational learning theory describes the changes associated with the ICT/IS evolution process through the concept of “learning curves,” which illustrate, for example, unit costs as a function of the number of times performed (Saarinen, 1989, p. 394). According to Saarinen’s work, “most of the IS evolution models have recognized learning to be one of the most important mechanisms. However, connections with existing learning theories seem to be weak and their potential to be only partially utilized” (idem, p. 394).

Finally, growth and stages theory describes the growth of an organisation in terms of sequences of distinguishable stages. According to this theory, organisations go from one stage to the following after reaching a crisis and undergoing a revolution that leads them to a new growth process.

Churchill’s model (Churchill et al., 1969), in which the idea of the stages theory was introduced to computing, proposed a number of levels of automation, from the simplest tasks to the automation of more complex tasks (such as making decisions based on strategic purposes). The early approaches of ICT evolution in translation firms suggested in the translation tools literature seem to have followed a similar path to the stages described by Churchill. These approaches (see, for example, Hutchins and Somers, 1992; Hutchins, 1996) understood the automation of the translation process as the “logical” aim of the translation tool development and use.

Nolan’s model (Nolan, 1973; Nolan, 1979) presented a more detailed account of the stages of IS growth in organisations, using budget growth as the primary indicator of the evolution, and implicitly based on the dynamic diffusion theory and organisational growth models (according to Saarinen, 1989). This model has been considered to be the most inclusive description of the evolution of IS in organisations (Saarinen, 1989), and although its validity has been criticised (Benbasat et al., 1984; King and Kraemer, 1984), researchers suggested its testing in small firms (Cooley et al., 1987; Stair et al., 1989), and studies on ICT adoption have drawn on it (see, for example, Cragg and King, 1993).

Churchill’s and Nolan’s models of stages of adoption have explained IS evolution in the broad context of organisations; however, many of the processes and management issues of large organisations are much simpler in the case of translation freelance businesses (see, for example, Joscelyne, 2003).

Research has showed that the models developed in the IS field do not take full advantage of the possibilities offered by the theories and models developed in the more mature fields of scientific inquiry, and that computer use is generally used to indicate the state and growth of computing, in spite of showing evidence that the extent of use (often measured by cost) has any direct effect on the level of benefits gained. Saarinen criticises that these models are descriptive and that they give no suggestions for evaluating the effectiveness of different ways of using computers, to conclude that “as long as technologies continue to develop, there will be a need for detailed models addressing the specific problems of each technology” (1989, p. 397).

In the translation sector, there have not been any models that have tried to explain ICT adoption until some have recently started to investigate certain aspects of using technology tools (cf. Chapter 3.4). For this reason, one of the aims of the present work is to look at how ICT adoption has been investigated in other disciplines, such as information systems, and use the suggestions and theoretical foundations offered by them to develop a suitable framework to investigate CAT tool adoption in the specific context of freelance translation businesses.

5.3.3. ICT adoption factors in SMEs: motivators and inhibitors

Another of the IS-related areas identified by researchers as key to understanding the adoption of new ICT is the analysis of factors that may affect the decision and the process of adoption (Cragg and Zinatelli, 1995).

In order to get an understanding of whether ICT are successfully adopted and used in firms or not, researchers have tried to identify the factors that affected positively and negatively the processes of adoption. Prior to the main stage of ICT adoption, there are a number of factors that can encourage or discourage the decision of adopting ICT, therefore leading SMEs to adoption or deterring them from adopting ICTs.

There is a body of literature that relates to ICT adoption and to the factors that encourage and discourage it. Researchers in this area which have analysed ICT adoption success factors, covered in the next section, have drawn on the literature that explores the motivators and the inhibitors for ICT growth in SMEs (for example, Cragg and King, 1993); and the literature on reasons for computerisation in SMEs (Easton et al., 1982; Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985; Malone, 1985; Baker, 1987; Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988; King and McAulay, 1989).

5.3.3.1. Motivators

Studies on ICT growth in SMEs, such as that by Cragg and King (1993), are based on previous research on factors that encourage or discourage computerisation in SMEs, and have distinguished a number of motivators that reflected internal, external and individual factors, such as relative advantage in information processing, relative advantage in planning and control, and relative advantage in work improvement. This group of motivators focuses on factors that give some kind of advantage (e.g. time, effort or economic savings), and the authors identify three more general factors related to external support (consultant support), competitors (competitive pressure) and CEO involvement (managerial enthusiasm). CEO enthusiasm toward computing was found to be the strongest motivating factor for ICT adoption and growth by Cragg and King. However, the nature of this involvement can vary from one CEO to another, as shown by Martin (1989), who revealed five types of involvement, ranging from remote to close involvement, as discussed later in this section.

Among the findings of the studies on the motivators for the computerisation of SMEs as stated above, there are some factors that have been identified as highly significant drivers to ICT adoption: the search for an increase in office task productivity (Easton et al., 1982; Baker, 1987), the improvement of information management and processing (Easton et al., 1982; Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985; Malone, 1985; Baker, 1987; Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988), and the effects of external information sources (Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988; King and McAulay, 1989).

More specifically, a desire for an increase in productivity, identified as a key persuasion factor by Baker, (1987), is a perceived benefit that allows SMEs to be more efficient and save time and effort (Cragg and King, 1993) through the automation of office tasks.

A higher capability of data processing (Easton et al., 1982; Baker, 1987), quicker processing of information (Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988), and therefore an improvement in information management are other factors that bring more savings in terms of time and effort (Cragg and King, 1993), help the firm to cope with information overload (Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985), and increase the performance of the firm through higher control for effective management (Malone, 1985).

External factors may also influence the decision of adopting ICT in a variety of forms; for example, through the influence of consultants that increase the willingness of CEOs to use ICT, either by recommending the firm to develop an ICT solution or by the consultant’s own use of technology (King and McAulay, 1989). Lefebvre and Lefebvre (1988) found some more external sources of information affecting ICT adoption, apart from consultants’ support, such as general environment, clients, competitors’ pressure (also identified by Cragg and King, 1993), employees and suppliers, although they did not find that these factors are clearly more important than others for their adoption.

Lefebvre and Lefebvre (1988) discuss that the decision of the small-firm manager is mainly influenced by information sources that are external to the firm, being that the manager is the person more likely to take the final decision, especially in SMEs, where the manager is much more prone to outside influence than managers of large firms (Malone, 1985).

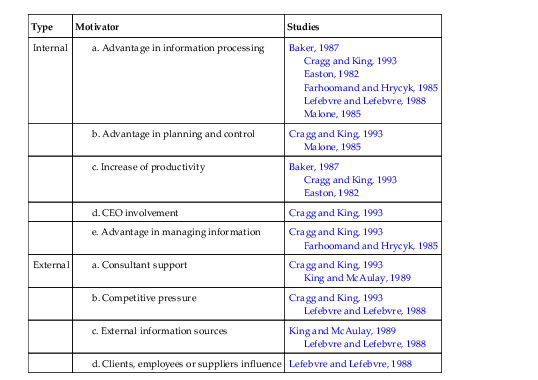

A summary of the factors positively affecting IS adoption in SMEs found in the reviewed literature is presented in Table 5.1. This categorisation classifies motivators into external and internal.

Table 5.1

Motivators affecting IS adoption in SMEs

| Type | Motivator | Studies |

| Internal |

a. Advantage in information processing

| Baker, 1987 Cragg and King, 1993 Easton, 1982 Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 Malone, 1985 |

|

b. Advantage in planning and control

| Cragg and King, 1993 Malone, 1985 | |

|

c. Increase of productivity

| Baker, 1987 Cragg and King, 1993 Easton, 1982 | |

|

d. CEO involvement

| Cragg and King, 1993 | |

|

e. Advantage in managing information

| Cragg and King, 1993 Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985 | |

| External |

a. Consultant support

| Cragg and King, 1993 King and McAulay, 1989 |

|

b. Competitive pressure

| Cragg and King, 1993 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 | |

|

c. External information sources

| King and McAulay, 1989 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 | |

|

d. Clients, employees or suppliers influence

| Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 |

In the freelance context, the role of the CEO is particularly important, since the manager of the freelance translation business is also the end-user of CAT tools. In the IS literature reviewed, CEO involvement and eagerness towards technology – called “managerial enthusiasm” by Cragg and King (1993) – has been confirmed to be one of the most important factors during the stage when the adoption decision is taken and once ICT have been adopted, for success in the use of the systems (DeLone, 1988). Freelance translators have to both make the decision to adopt CAT tools and use them. Therefore, it is relevant to examine studies that have analysed CEO involvement in more depth, such as Martin (1989), who identified a range of different involvement patterns among CEOs in SMEs, and categorised them into five groups of behaviour patterns. Table 5.2 shows the five types of CEO involvement identified by Martin.

Table 5.2

Types of CEO involvement in computerisation in SMEs (Martin, 1989, p. 192)

| Type | Behaviour pattern |

| 1 | Top manager is remote from the computer resource, and is uninvolved even in key decisions in relation to its development or operation. |

| 2 | Top manager is involved in a managerial, supervisory capacity, and identifies goals and sets targets. |

| 3 | Top manager is closely involved in implementation, and takes part in detailed choice and/or design decisions. |

| 4 | Top manager is directly involved technically, and takes part in programming or spreadsheet development. |

| 5 | Top manager routinely interacts directly, hands-on, with the IS. |

Although Martin’s classification of CEO involvement looks at the role of managers in larger organisational contexts, it is important to observe that all the behaviour patterns described in levels 2 to 5 are present in the figure of the freelance translator adopting CAT tools. Level 1 cannot apply to the freelance translation context because it describes a remote involvement, which in the case of freelance translators does not exist.

The role of the CEO in freelance translation businesses, among other motivators identified (e.g. advantages of adopting ICT, influence of external sources), is something that will need to be investigated in this study to gain a better understanding of the characteristics of the freelance translators underpinning the adoption of CAT tools.

5.3.3.2. Inhibitors

In the same research conducted by Cragg and King (1993) about motivators, the inhibitors of ICT growth are also explored, again based on previous studies on computerisation in SMEs (Bourner et al., 1983; Baker, 1987; King and McAulay, 1989). According to Cragg and King’s (1993) study, the most significant factors that deter SMEs from adopting ICT identified by the authors can fall into broader categories: ICT education factors (such as lack of CEO or personnel with broad ICT knowledge, lack of personnel with specific ICT skills, and negative influence of higher levels), lack of managerial time, economic factors (such as an inappropriate economic climate, excessive costs, and firms being too small), and technical factors (such as having an unstructured system, and having poor software support).

As corroborated by other studies (Baker, 1987; Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988; King and McAulay, 1989), the lack of general ICT knowledge has been found to be the most important inhibitor for ICT adoption and growth, together with a lack of economic resources. These two factors become accentuated in the case of SMEs, where economic resources available for ICT investments are more limited than in large companies. The fact that many SMEs do not even have a department devoted to ICT support, together with the tendency to employ more generalist than specialist staff, makes it more difficult for them to have a high internal ICT knowledge. For this reason, another major inhibitor of ICT adoption is the influence of the person that has to make decisions regarding ICT, generally the CEO. Since CEOs may not have a high ICT knowledge either, their decision tends to depend on their enthusiasm towards technology and the confidence they may have in external support, such as consultants or vendors (Kole, 1983; Baker, 1987; King and McAulay, 1989; Gable, 1991).

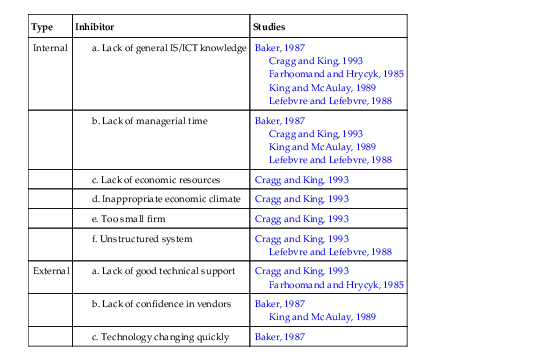

A summary of the factors that deter the adoption of ICT in SMEs found in the literature is presented in Table 5.3. This categorisation classifies inhibitors into external or internal factors to the organisation.

Table 5.3

Inhibitors affecting IS adoption in SMEs

| Type | Inhibitor | Studies |

| Internal |

a. Lack of general IS/ICT knowledge

| Baker, 1987 Cragg and King, 1993 Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985 King and McAulay, 1989 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 |

|

b. Lack of managerial time

| Baker, 1987 Cragg and King, 1993 King and McAulay, 1989 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 | |

|

c. Lack of economic resources

| Cragg and King, 1993 | |

|

d. Inappropriate economic climate

| Cragg and King, 1993 | |

|

e. Too small firm

| Cragg and King, 1993 | |

|

f. Unstructured system

| Cragg and King, 1993 Lefebvre and Lefebvre, 1988 | |

| External |

a. Lack of good technical support

| Cragg and King, 1993 Farhoomand and Hrycyk, 1985 |

|

b. Lack of confidence in vendors

| Baker, 1987 King and McAulay, 1989 | |

|

c. Technology changing quickly

| Baker, 1987 |

The inhibitors identified in the literature about ICT and SMEs represent a valuable set of factors that need to be investigated to gain a better understanding of the characteristics of the freelance translators hindering the adoption of CAT tools. For example, factors such as the “lack of managerial time,” the “lack of expertise” or the “lack of economic resources” which affect SMEs in their adoption of ICT, are particularly likely to affect micro businesses, like freelance translation businesses, where the translator is also the owner-manager of the business. Similarly, some external inhibitors that might affect freelance translators are the existence and reliability of external support in the shape of consultants and mostly vendors, who can provide freelance translators with the right training and technical support that allow them to cope with the fast changes that the technology used by freelance translators is experiencing (Pérez, 2002; Joscelyne, 2003).

5.3.4. Success factors for ICT implementation in SMEs

Success factors have also been studied in the area of information systems that looks at ICT adoption in SMEs. The concept of “information systems success,” also called by some authors “IS effectiveness” (Hamilton and Chervany, 1981; Raymond, 1990; Thong et al., 1996), is recognised by many researchers as difficult to define (as shown, for example, by Weill and Baroudi, 1990).

A number of studies have investigated the factors contributing to IS success in the context of small firms. For example, Raymond (1985) investigated the relationships between organisational characteristics and IS success based on the studies of Ein-Dor and Segev (1982), DeLone (1981) and Turner (1982). Raymond used user information satisfaction and level of system satisfaction as measures of IS success, and the findings revealed that systems success was higher where a greater proportion of applications were developed and used internally, a greater number of administrative applications were used, interactive applications had been implemented, and the IS function was situated at a high organisational level.

Similarly, other studies examining the factors that affect the successful use of IS by SMEs found not only a positive association of IS success with the CEO knowledge of computers, but that CEO involvement was a key factor for IS success (DeLone, 1988; Montazemi, 1988; Palvia et al., 1994; Caldeira and Ward, 2002).

The factors affecting IS success in small businesses that were found to be significant in previous studies were categorised into four major classes (organisational characteristics, organisational action, system characteristics and internal expertise), plus a fifth category regarding external expertise by Yap et al. (1992), leading to the development of a descriptive model of key factors to IS success in a small business context.

External factors affecting IS success were further investigated by Soh et al. (1992), Palvia, (1996), Thong et al. (1996) and Igbaria et al. (1998), and the computerisation success of SMEs was associated with the capability, experience and effectiveness of the consultant.

There are some inconsistencies in the findings of all these studies; however, the positive association of IS success and a higher involvement of the CEO in SME computerisation was supported by most of the studies (DeLone, 1988; Yap et al., 1992; Palvia et al., 1994). Cragg and Zinatelli (1995) attribute this inconsistency in the findings to the evolution of IS and changes in the factors affecting its success over time.

This review of the studies carried out in the IS domain regarding IS success factors is particularly important for the present research due to the lack of much formal research focused on CAT tool adoption and the factors that contribute to its success in the translation studies area. However, the analysis of IS success factors in previous research on IS presents a number of factors (such as CEO involvement in CAT tool adoption, or the influence of software consultants/vendors) that needed to be investigated with regard to CAT tool adoption by freelance translation businesses.

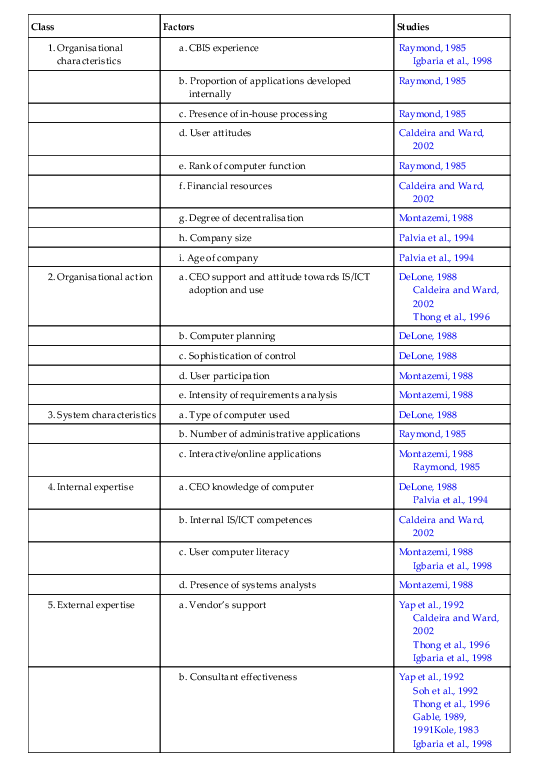

A summary of the factors affecting IS success in SMEs found in the literature reviewed is presented in Table 5.4. This categorisation is based on Yap et al.’s (1992) classification, and includes a fifth category regarding external expertise identified in the same study, as well as adding factors found in subsequent studies.

Table 5.4

Classes of factors affecting IS success in SMEs

| Class | Factors | Studies |

|

1. Organisational characteristics

|

a. CBIS experience

| Raymond, 1985 Igbaria et al., 1998 |

|

b. Proportion of applications developed internally

| Raymond, 1985 | |

|

c. Presence of in-house processing

| Raymond, 1985 | |

|

d. User attitudes

| Caldeira and Ward, 2002 | |

|

e. Rank of computer function

| Raymond, 1985 | |

|

f. Financial resources

| Caldeira and Ward, 2002 | |

|

g. Degree of decentralisation

| Montazemi, 1988 | |

|

h. Company size

| Palvia et al., 1994 | |

|

i. Age of company

| Palvia et al., 1994 | |

|

2. Organisational action

|

a. CEO support and attitude towards IS/ICT adoption and use

| DeLone, 1988 Caldeira and Ward, 2002 Thong et al., 1996 |

|

b. Computer planning

| DeLone, 1988 | |

|

c. Sophistication of control

| DeLone, 1988 | |

|

d. User participation

| Montazemi, 1988 | |

|

e. Intensity of requirements analysis

| Montazemi, 1988 | |

|

3. System characteristics

|

a. Type of computer used

| DeLone, 1988 |

|

b. Number of administrative applications

| Raymond, 1985 | |

|

c. Interactive/online applications

| Montazemi, 1988 Raymond, 1985 | |

|

4. Internal expertise

|

a. CEO knowledge of computer

| DeLone, 1988 Palvia et al., 1994 |

|

b. Internal IS/ICT competences

| Caldeira and Ward, 2002 | |

|

c. User computer literacy

| Montazemi, 1988 Igbaria et al., 1998 | |

|

d. Presence of systems analysts

| Montazemi, 1988 | |

|

5. External expertise

|

a. Vendor’s support

| Yap et al., 1992 Caldeira and Ward, 2002 Thong et al., 1996 Igbaria et al., 1998 |

|

b. Consultant effectiveness

| Yap et al., 1992 Soh et al., 1992 Thong et al., 1996 Gable, 1989, 1991Kole, 1983 Igbaria et al., 1998 |

5.3.5. SMEs and ICT sophistication

It has been noted in a number of studies that one of the fundamental problems that IS researchers face is to characterise organisational information systems, and particularly identify different criteria of systems “maturity” or “sophistication” (Benbasat et al., 1980; Cheney and Dickson, 1982; Ein-Dor and Segev, 1982; Saunders and Keller, 1983; Gremillion, 1984; Lehman, 1985; Mahmood and Becker, 1985; Raymond, 1988; Raymond and Paré, 1992).

“ICT sophistication” is defined by Raymond and Paré (1992) as a multi-dimensional construct which refers to the nature, complexity and interdependence of ICT usage and management in an organisation. Therefore, the concept of ICT sophistication integrates both aspects related to IS usage and IS management, also present in Nolan’s model of stages of growth (Nolan, 1973; Nolan, 1979). Raymond and Paré (1992), based on variables from previous research to characterise each dimension, identified four dimensions within the construct related to technological support (technological sophistication), information content (informational sophistication), functional support (functional sophistication) and management practices (managerial sophistication).

Technological sophistication refers to the number and diversity of information technologies used by SMEs as well as to the nature of the hardware and the development tools used by the firm.

Informational sophistication refers to the nature of the application portfolio of the SME, including both transactional and administrative applications. Another aspect of informational sophistication identified by Ein-Dor and Segev (1982) relates to the degree of integration of the applications, in an SME basically characterised by the presence of software (e.g. database) or hardware (e.g. local area network) that allow information interchange and resource sharing.

Functional sophistication relates both to the structural aspects of the IS function in the SME (e.g. the location and autonomy of the IS function and the number of internal IS specialists) and to the ICT implementation process (e.g. method, source and uniqueness of applications).

Managerial sophistication relates to the mechanisms employed to plan, control and evaluate present and future applications (e.g. written documents, formalism of process, position of responsible individual and level of alignment with organisational objectives).

For the particular interest of our work, the “technological sophistication concept” developed in IS research was likely to help in understanding the conceptual framework of CAT tool adoption by providing the theoretical foundations used in this area to understand ICT adoption in the context of freelance translation businesses. In addition, Raymond and Paré developed and used an instrument based on the sophistication concept that can contribute to the development of the instrument measuring CAT tool adoption and the adoption of other ICT in the freelance translation business. In the absence of instruments to measure ICT adoption in the translation field, Raymond and Paré’s instrument represented a useful and validated contribution to the measurement of ICT adoption to be tested in the freelance translation business context.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.