9

From PLEs to PLWEs: a Multilingual Information Management System

Abstract

A Multilingual Information Management System (MIMS) as an integrated approach of the concepts of information management, information systems, information literacy and translation technology is a comprehensive proposal to deal with the complexity of information overload and efficient communication faced by multilingual information professionals. This chapter presents the outcome of an interdisciplinary approach to contribute to the development of this community of practice’s professional and information competence by providing a strategic framework that supports their productivity and helps them to evolve with the changes with a lifelong learning vision.

Keywords

Multilingual Information Management System

MIMS

information management

information systems

information literacy

translation technology

multilingual communication

multilingual information professionals

The proposal of a Multilingual Information Management System (MIMS from here on) introduced here is the result of the interdisciplinary approach to Multilingual information Management described throughout the book. It draws on the IS and IL concepts reviewed in the first part of the book, as well as in the study of the professional environment of MIPs, first addressed from the existing body of literature, also in the first part, and then enhanced by the development of a framework based on empirical research in the second part of the book. Therefore, the proposed MIMS enlarges the scope of core translation production within a multilingual working environment to add systems that support management and administrative activities as well as information and knowledge management within professional practice, and contributes to improving productivity, efficiency and decision-making.

Personalised information systems in knowledge-based working settings have been criticised for providing limited success because the systems have been designed according to what the technology can do rather than focusing on the user’s perspective of what the work requires (Kuhlthau and Tama, 2001, p. 40). In line with the proposed approach so far and with a focus on the MIP and his or her business, rather than on the features of the available technology, the conceptualisation of the MIMS that follows takes into consideration the approach provided by Personal Learning Environments, their application to professional contexts, and the particular environment of MIM.

9.1. Personal Learning Environments (PLEs)

Information overload has been present along the discussion of previous chapters due to the problems it causes for those professionals working in multilingual communication. However, it also has the view that this larger-than-ever breadth of information sources and ICT within our reach provides a richer-than-ever environment for accessing information and knowledge and for facilitating continuous learning, i.e. lifelong learning, if the tools and resources – material and human – are used in a suitable way. This view aligns very much with that of Personal Learning Environments (PLEs), which Adell and Castañeda essentially defined as “the set of tools, sources of information, connections, and activities that each individual regularly uses to learn” (2010, author’s translation).1

PLEs as such have always existed among people, although there has been a renewed academic interest in them since the advent of Web 2.0 and they have arisen as an educational approach to integrating the current environment of learners in the context of the information society, heavily influenced by the empowerment of social networks and the ease of accessing information through Web 2.0 (Buchem et al., 2011). It is important to highlight that PLEs are not a technology or a system themselves, but an approach to taking advantage of the current ICT to teach and learn (Castañeda and Adell, 2013, p. 29). Another important assumption highlighted by Castañeda and Adell is that PLEs are not tightly subject to any particular didactic prescriptions, but rather on the contrary, they look to build each individual’s learning environment by dynamically making knowledge explicit, managing it and generating connections with the components of this pedagogical ecosystem, be they sources of information or other individuals sharing knowledge. From a pedagogical theory perspective, the PLE approach is closely related to the ideas advocated by Vygotsky’s socioconstructivism (1978) and with a more recent pedagogical current of connectivism (Siemens, 2005; Calvani, 2009; Downes, 2010). Thus, PLEs require a proactive approach to learning, both from teachers and learners, based on social interaction with peers, available sources of information, and ICT. In fact, learners can contribute to the environment with their input and eventually assume a teaching role, and similarly, teachers who are actively involved in a PLE will also become learners at some point during the teaching-learning process. This bi- or multi-directional flow of knowledge and learning is what makes PLEs a perfect candidate for facilitating lifelong learning, “learning to learn in the digital age” in Castañeda and Adell’s words (2013, p. 22). Given this social commitment and involvement of the learning process within a technology-based environment an updated and more comprehensive definition has recently been provided by Attwell et al. (2013, p. iv): “a pedagogical approach with many implications for the learning processes, underpinned by a ‘hard’ technological base. Such a technopedagogical concept can benefit from the affordances of technologies, as well as from the emergent social dynamics of new pedagogic scenarios.”

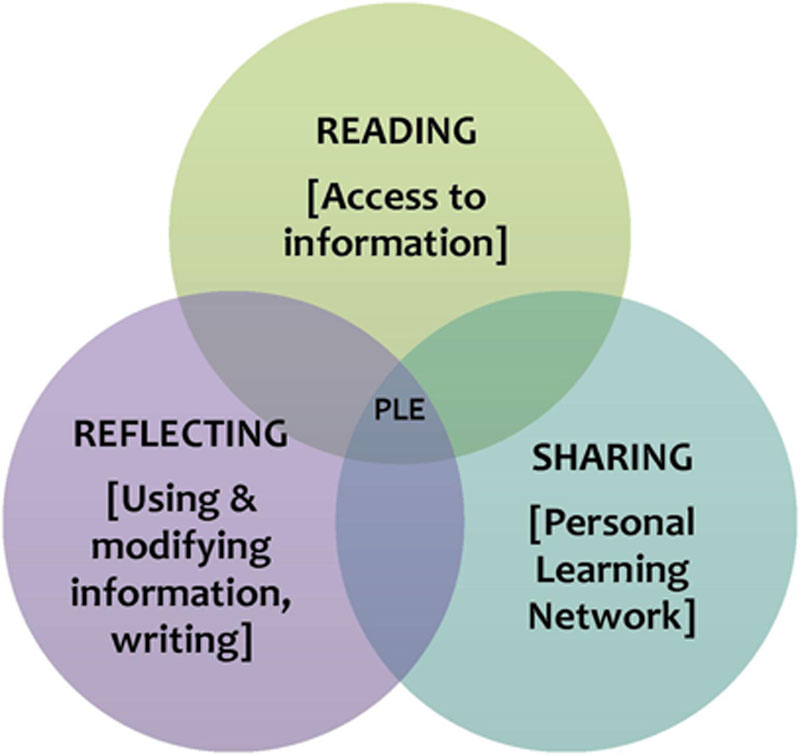

To understand how a PLE works it is important to be aware of the three interrelated pillars that integrate this ecosystem (see Figure 9.1.), namely, accessing information and reading it, reflecting and writing about it, and sharing knowledge and learning.

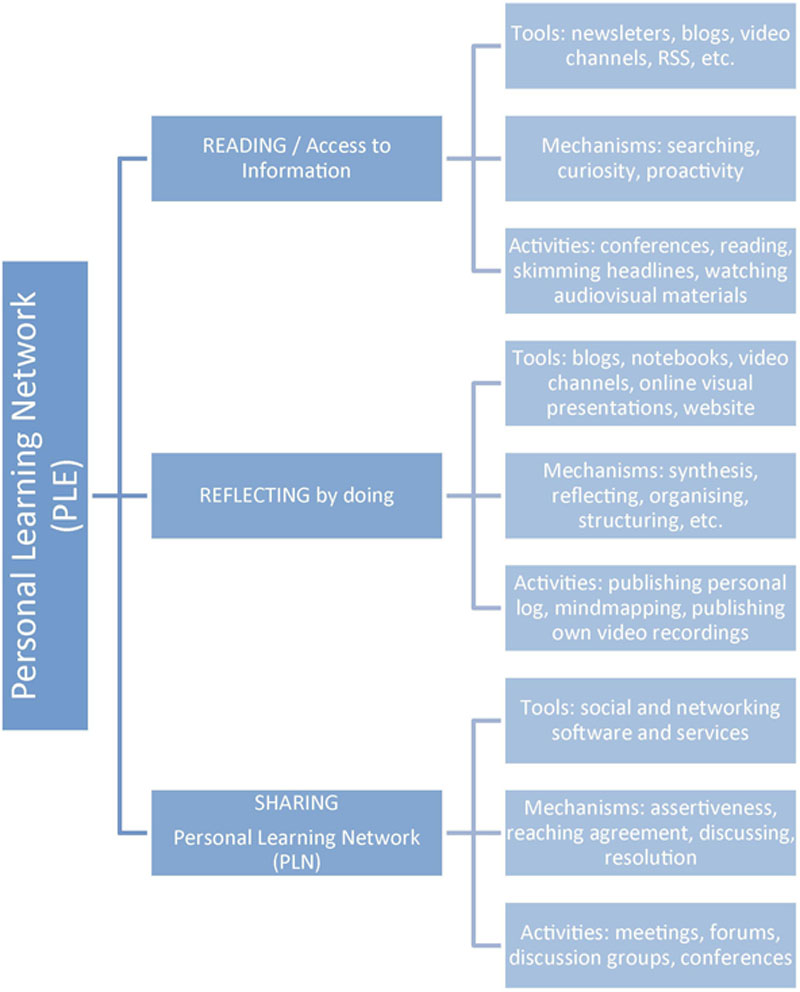

In giving an example of what a PLE involves, a myriad of diagrams and visualisations of individual PLEs can be found on the Internet;2 however, from a formal and rigorous analysis a comprehensive conceptualisation is presented by Castañeda and Adell (2013, p. 20), which also gives an example and has evolved from their work in 2010 to the version in 2013. Figure 9.2 presents an adaptation of their conceptualisation of a PLE.

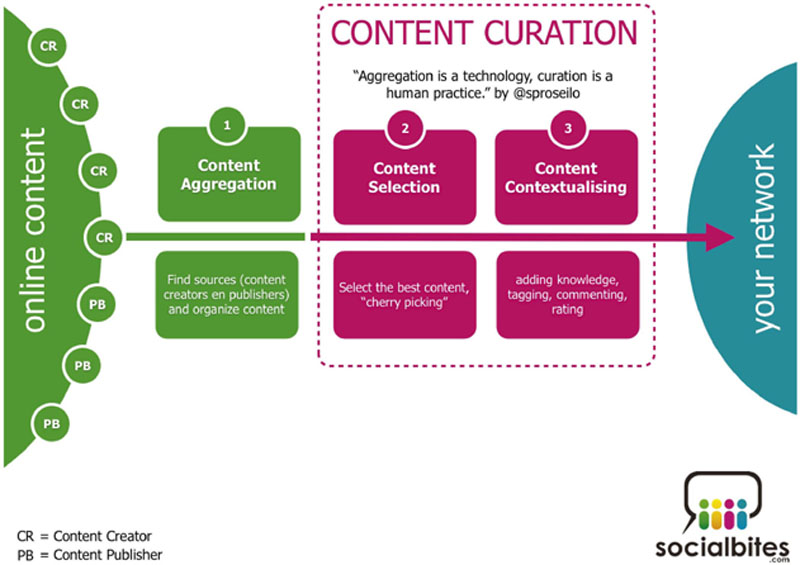

A practice that is becoming more and more popular among online communities as a way to share information and that falls into the kind of practices that are part of a PLE is information curation (c.f. Chapter 6, section 6.3.1.4.). Originating in the context of the modern version of the old practice of archiving (Joint Information Systems Committee, 2003), curation is understood in the sense of preserving personal digital archives for future consumption (text- or multimedia-based), as opposed to the idea of immediate consumption as we access it (Whittaker, 2011, p. 5). Actually, Whittaker states that for most types of personal information, people’s behaviour seems to be much closer to curation than consumption. Similarly to PLEs, information archives have always existed, but with the growth of digital content, the ease for accessing information and storing it, and the proliferation and empowerment of online social networks, information curation is becoming a growing trend which is actually affecting the way people consume goods (Colombani and Videlaine, 2013). Figure 9.3. shows a diagram about content curation published by Socialbites.com (website not available anymore) that presents a process very similar to that of PLEs.

Figure 9.3 Content curation process

9.2. Personal Learning and Working Environments (PLWEs)

PLEs, if viewed from a systemic point of view (c.f. Chapter 2, section 2.1.3.), share a number of similarities with information systems. A PLE is a system from the very moment it is an environment that connects several components to work together towards the objective of learning, there are continuous inputs and outputs – a multidirectional flow of information. It is also closely related to the knowledge generation processes of information systems, since the main asset being exchanged is information that, eventually, generates knowledge. There is also an element in common with IS strategy, since the way a PLE is created and the way it changes and evolves has a lot to do with the decisions being made at its conception, e.g. how a PLE is organised, and with the goals that are set initially and at a longer term, i.e. there is a main learning objective for developing a PLE and there are choices that are made to best accomplish it. Therefore, there is strategic thinking guiding the conception of a PLE (c.f. first conception of IS strategy in Chapter 5, section 5.2.), there is a tactical approach to decide what assets should be part of a PLE (c.f. second conception), i.e. what components form the PLE in terms of tools, resources, people, and there is an overall perspective of a PLE that socially defines and situates each individual behind it (c.f. third conception).

PLEs have been conceived to address the educational scenario of our current society, where Web 2.0 and the social face of the Internet have transformed the way in which people are connected to each other and share information and knowledge. This fact has not only affected the way we learn, but also the way we work; therefore, PLE-like approaches cannot only be useful for self-development and learning, but also for continuing this learning throughout ones’ professional activity and for supporting information management as part of professional practice (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Jarche 2008). A previous conception of this view from a Knowledge Management angle was the figure of an eProfessional, as a variation of the eLearner, and tagged this application of the PLE concept to a working setting as a Personal Learning and Work Environment (PLWE) (Rubio et al., 2011).

Scholars have also recently pointed towards adopting a PLE-like approach in higher education training as an early contact to a setting which is similar to the professional practice context of translators (Cánovas 2013). This view, in addition to replicating part of the social environment of translators, also shows an information literacy approach towards creating a personal knowledge base which arises from the learning experience acquired through formal training and that should grow and evolve in parallel to the professional behind it. In this application of a PLE and an IL to professional practice further support is also required to make informed decisions about how strategically to mature this environment to meet business goals and provide competitive services, how to tactically operate within the working environment to be efficient at managing all the information and information sources, and how to convey this vision to others. This additional support can be provided in the form of an MIMS.

9.3. A Multilingual Information Management System

Returning to the MIM context, the application of the PLWE approach with the addition of the IS and IL input defines the holistic understanding of an MIMS that can enhance the professional practice of MIPs, as an intense knowledge activity (Sales et al. forthcoming) and that does not only rely on material sources of information, but also on human ones (Montalt i Resurrecció, 2009, p. 174). This is particularly relevant and required for those working in specialised contexts, such as legal, medical or technical multilingual communication (García Izquierdo and Borja Albi, 2009; Borja, 2005).

As stated at the beginning of the book, both formal and informal communication can lead to the generation of knowledge (c.f. 2.1.2), although if information is not formalised, it is much more difficult to manage it so it can be accessed when is required or can support decision-making. As stated by Li (2009, p. 19), “In today’s information society, heterogeneous data and information can be dynamically accessed, converted, disseminated, distributed, located, processed, and stored across diverse applications, channels, databases, networks, platforms and systems,” but to do it efficiently within a working setting it needs to be suitably managed. This is also the case in MIM, where information comes from a vast range of sources that needs to be organised to be processed and eventually retrieved.

As it happens with the competition between finding MT systems that replace human translators (c.f. efforts towards FAHQT in Chapter 3) and developing tools that support translators’ work at their core function, i.e. CAT tools (c.f. Chapter 3), in the IS field, Decision Support Systems were designed to support rather than replace decisions within an organisation. Similar to this overall resemblance, DSSs involve flexible interactive access to data. They are designed with an understanding of the requirements of the decision makers and the decision-making process in mind to deliver the right information at all levels of operation, including end-users.

Information access has greatly improved due to technological developments; however, an integrated system such as the proposed MIMS should aim at improving MIP effectiveness and efficacy by providing support at the functions integrated within a MIM environment (c.f. Chapter 6, section 6.3.1. for a more detailed description of the ICT support for the activities behind the functions), particularly at the following strategy levels:

Tactical-operational level: administrative tasks that can be automated to some extent at all levels of operation are required in order to improve productivity and be able to focus on core functions. This involves, for example, from basic clerical and communication tasks to more advanced online communication activities, budgeting, invoicing, and tax and accounts management tasks (c.f. Chapter 6.3.1.4. and 6.3.1.6).

Tactical-strategic level of information management: all the information-related tasks that require a query to cover a need depend upon a reliable and effective system that captures, stores, organises and delivers the most suitable piece of information for each case, be it a business-related need or a language specific one. The former include, for example, client databases, finance reports, direct or social communications, and marketing materials. Among the latter knowledge bases, terminology collections, translation memories, multilingual corpora, reference materials, online communities or domain experts, or the generation of multilingual documents (c.f. Chapter 6.3.1.2. and 6.3.1.3.).

Managerial-strategic level: an increased support for tasks performed by MIP in the decision-making area is required for making timely and knowledgeable decisions at all levels of operation (c.f. Chapter 5.2.), from evaluating the value and feasibility of undertaking potential projects, to defining language-, culture- or market-specific strategies that will guide the whole linguistic transfer of information, and through the preparation of support resources to optimise the formulation and quality assessment of translations (c.f. Chapter 6.3.1.1., 6.3.1.3. and 6.3.1.5.).

9.4. Structure of an MIMS

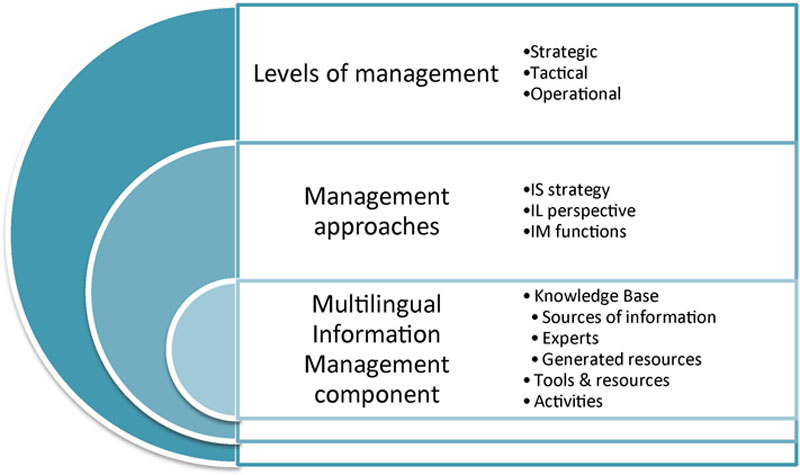

In order to cover the needs of the system, a suitable structure should include the following components that have been presented in detail throughout the book (Figure 9.4):

• the levels of management required: strategic, tactical and operational;

• the approaches/views that regulate each of these levels: the information systems strategy, the information literacy approach and the information management activities;

• the core MIM component that includes an integrated view of the sources of information, tools, resources and people that are part of the business activity.

Figure 9.4 Components of an MIMS

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.