2. Advice to Ignore

“For better or for worse, the U.S. economy probably has to regard the death of equities as a near-permanent condition—reversible some day, but not soon.”

Business Week’s Aug. 13, 1979, “The Death of Equities” cover story

The most derided magazine cover of the last three decades, the one held up for the most ridicule (other than perhaps Time magazine’s famous alteration of O. J. Simpson’s mug shot), was Business Week’s mid-1979 cover story, “The Death of Equities.” It’s been an article of faith that the story is Exhibit A in the long history of evidence for investors to consider media a contrarian indicator for market trends: If a leading publication says the rally is over, it’s time to start buying. If stocks look cheap, according to Smart Money or Kiplinger’s or worse yet, Newsweek or another general-interest publication, they’re obviously expensive. (This goes triple if the stock market somehow lands on the cover of Playboy or Golf Digest.)

But the derision aimed at Business Week’s famous cover story is somewhat misplaced. The article ran in 1979, and stocks didn’t start to recover until 1982, after which they began a historic bull run that lasted 18 years. For three years, this article appeared astute and prescient. Considering current investing habits, where investors turn over their portfolio in a matter of weeks, three years might as well be a lifetime.

That’s not to say the story got it right: It features its share of myopic pronouncements, particularly about the outlook for stocks (the article suggests Wall Street was unlikely to try to revive interest in equities through a promotional campaign because of the other investment possibilities that existed at that time).

The tone of the article suggested that a revival of equity interest was not likely, but the conditions BW said were necessary for a rebound came to pass. In the piece, the authors wrote that “to bring equities back to life now, secular inflation would have to be wrung out of the economy, and then accounting policies would have to be made more realistic and tax laws rewritten.”1

Basically, that’s what ended up happening. On some level, though, it’s hard to blame the writers. Inflation was rampant in the late 1970s, and the political will to confront that had been missing at the Federal Reserve, the central banking authority in the U.S., for years. Notably, the article was published August 13, 1979—one week after the appointment of Paul Volcker to head the Federal Reserve. The previous chairman, G. William Miller, lasted just 17 months on the job and was deemed “the most partisan and least respected chairman in the Fed’s history,” according to veteran Federal Reserve watcher Steven Beckner, in his book Back from the Brink: The Greenspan Years. Miller and his predecessor, Arthur Burns, pursued policies that allowed inflation to rise, rather than reining it in. Volcker’s efforts—raising rates into double-digit territory—finally broke the back of inflation. While the subsequent tenures of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke garner mixed reviews, Volcker’s reputation as a central banker is impeccable.

The Business Week article was wrong in many ways, but the popular view that its cover story could be heralded as a turning point in stocks is off the mark, too. At the very least, the Business Week article was attempting to dissect how inflation was ruining stock returns (it was) and how current fiscal and monetary policies were constraining capital investment (they were). They did at least point out that certain changes would have to come to pass for stocks to regain their mojo, and those changes did come to pass. Similarly, in 2010, for the stock market to put together a sustained advance based on something other than borrowed money, worrisome issues of inflation, debt burdens, and economic malaise will have to be combated.

Besides, if people want to point fingers at the media for poor predictions, there are much better, more recent examples! For one thing, at least Business Week did not advise investors on what stocks they should pick. Those that have done this in recent years, well, one would have made a fortune shorting against just about all of the names that came up. The best of these would be any major magazine that made a habit out of picking individual stocks over the last couple of decades, and in particular a pair of comically terrible predictions made by Fortune magazine and Smart Money magazine at the end of the century. The two magazines drew up lists of stocks to buy for the coming decade, and it’s hard to imagine they could have made worse selections if they’d allowed chimpanzees to do the work for them.

The worst part about all of it is that these picks, on some level, have sensible, rational arguments behind them, and you’ll find that in the stock market, the investments that frequently doom the most people are the ones that seem all the more plausible because of a company’s unique position in a market, or because a certain sector of the economy appears poised to grow at a tremendous rate as the public warms to a new technology. Fad investments make suckers out of people, but not as many as those ideas that prove disastrous just because they seem so plausible.

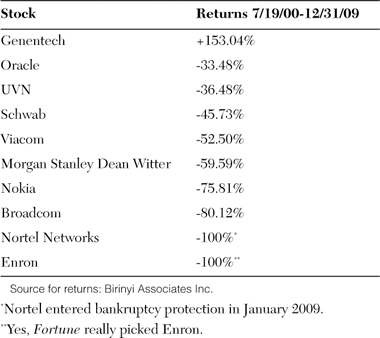

Let’s start with Fortune magazine, which in August 2000 put together a list of ten stocks to buy for the coming decade, with this whopper of a headline: “A few major trends will likely shape the next ten years. Here’s a buy-and-forget portfolio to capitalize on them.”2 Buy and forget, they suggested. Not only were they so confident that these were the best picks out there, you could afford to not even pay attention. And you might ask, who would listen to such a thing? Well, plenty of people did, and plenty of people will again in the invariable next bull market, when such articles need to be ignored. But I digress—if you followed this advice, the only thing to forget about was your money. Table 2.1 shows Fortune’s list, notable mostly for how horrid the picks turned out.

Table 2.1. Fortune Magazine’s List of “Ten Stocks to Last the Decade” in 2000

There you have it. There’s one winner in this group—Genentech, which did well due to breakthroughs in biotechnology. The list includes Morgan Stanley Dean Witter (ugh) and even worse, Enron, the energy company that turned out to be, more or less, a rigged trading operation. Overall, the portfolio dropped by 43 percent for the decade (if the stocks are equal-weighted), compared with the 24 percent drop in the S&P 500 index in this period of time.

Yet, Fortune magazine continues to publish picks of stocks every year, throwing out their best investment ideas without a real road map of how much to buy of each one, whether to divide one’s portfolio up evenly, or when to take profits or sell outright (the magazine does a midyear update on the stocks, but that’s it). The magazine, like other publications, has restrictions as it is not a registered investment advisory, so it can’t constantly update its list or write recommendations each time something changes. Their track record invariably contains a number of years where the stocks they picked outpace the market, and then in other years, trail the broad averages, but there’s no blueprint, no allocation to follow, and no accountability other than a year-end reckoning on how the picks did. (Is one expected to sell all of the positions at the end of the year and then buy the new ones? How does this work, exactly?) And for as much credibility as the magazine has as an investigative enterprise, there’s no reason to expect it will have any ability to outdo the market in a long period of time. So why bother? They’d probably argue that there’s an element of sport in all of it, but this is your money, and shouldn’t be given over to the whims of a magazine editor.

They’re not alone; other major investing publications have similar lists. And if it can be proven that supposed experts in the field—fund managers, institutional investors, and financial advisors—are lousy at picking individual stocks, well, the same can be said for journalists. Professional money managers are thought of as having high qualifications, but as we shall see, their returns tend to fail to match the long-term averages. But their track record is stellar when compared with those who are a few notches down on the totem pole in terms of qualifications—financial advisors, newsletter writers, and finally, journalists. This is not to deride the media, of which I am a proud member, but individual members of the Fourth Estate are notoriously poor at picking stocks, and their value is better put to use with investigative work of companies (think Bethany McLean, also of Fortune, paramount in exposing the accounting fiction that was Enron, which the editors believed was one of the best picks for the decade a couple of years earlier).

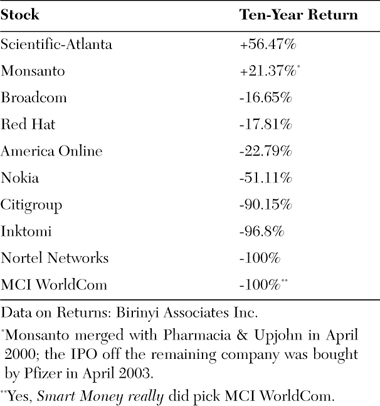

Smart Money’s list published in late 19993 is likewise an amazing document to behold. It contains exactly two stocks that actually did well, like Monsanto, and then a handful of absolute portfolio killers: Citigroup, which was riding high in 1999 but imploded late in the decade; America Online, the product of one of corporate America’s worst mergers, the marriage of AOL and Time Warner, which the latter is still trying to live down after years of wealth-destroying performance of its shares; and MCI WorldCom, the other accounting fiction of the decade that blew up a few years later, and somehow didn’t make it into Fortune’s 2000 list of recommended stocks. Overall, a simple average of the portfolio—the surviving stocks, anyway—gives you an average return of minus 42 percent, just as bad as the Fortune list.

What’s interesting as well is that the list published includes a column, next to the stock prices, of each issue’s price-to-earnings ratio at the time. For the uninitiated, the price-to-earnings ratio measures a company’s yearly earnings (let’s call it $1 per share) and divides that into the share price (say, $20). It is one of the most commonly used ways to value stocks. Companies with higher growth expectations can command higher price-to-earnings ratios because investors can be reasonably assumed to pay more for stronger growth; those with lower expectations have lower ratios. On average, the S&P 500 has been around 16 for its lifespan. In the simplest explanation, a price-to-earnings ratio of a company that falls below its long-term average likely means the stock is undervalued. A P/E ratio that’s above that potentially means the stock is overvalued.

That makes the P/E ratios of these selections even more ridiculous. The lowest? Citigroup, at 15.5 times earnings, which can be considered a reasonable valuation. Half of the ten stocks listed have P/E ratios above 40. That’s far too high to be considered a potential growth candidate. The top P/E of 297.3 was Inktomi, a company that provided software for Internet service providers. On October 22, 1999, the stock closed at $103.06 a share—less than half its peak, which came later, at $241 a share in March 2000. In 2002, the company was acquired by Yahoo for a paltry $235 million, or $1.63 a share.

The list is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2. Smart Money’s “Ten Stocks for the Next Decade” in 2000

So that’s two winners, three stocks that did poorly but still stayed ahead of the S&P 500’s dismal returns for that period, and five unmitigated disasters. It’s further interesting that the two stocks that somehow made it into both lists published by Fortune and Smart Money are two of the worst investments: Nortel Networks and Broadcom.

The Nortel Flameout

Nortel stands as one of the great stock-market blowups of the last couple of decades. Fortune magazine, in its 2000 article touting Nortel as one of the stocks for the decade, quoted Steve Harmon, a “tech guru” who founded Zero Gravity Internet Group, saying that Nortel, based on its market share of optical networking systems, could “become the GE of technology the way they are operating.” Of course, this was a decidedly 1990s view (magazines have since stopped quoting “tech gurus,” for one).

The company, based in Toronto, was a spin-off of Bell Telephone Company of Canada, separating from its parent in 1895 because it wanted to build products other than telephones. It continued this way for decades, eventually producing telegraphic switchboards for military operations, and later pioneering a digital central office switch produced in the mid-1970s that served more than 100,000 office lines at once. And it became a huge player in the global fiber optic networking space in the mid-1990s.

But the stock price was clearly just not sustainable, something the editors of Fortune should have realized when this sentence was approved for publishing: “Like a lot of stocks in this sector, Nortel’s isn’t cheap. It trades at a P/E of around 114, bolstered by a 52-week gain of 250.” The alarm bells should go off all over the place when reading that line. At the beginning of it, the author is rationalizing, saying its expensive profile is “like a lot of stocks” in the sector, which must somehow make it tolerable. Then he tells you the facts—a price-to-earnings ratio of 114, a mind-blowing number, as it had gained 250 percent in the last year. With the exception of stocks that are trading at 50 cents each, you just don’t gain 250 percent in a year without consequences. In September 2000, Nortel had a market capitalization of $398 billion in Canadian dollars, or about $254 billion U.S., which accounted for one-third of the market cap of the entire Toronto Stock Exchange (when one company is the bulk of any market, it’s a bad sign). By August 2002, the market cap had dropped to about $3.2 billion, and it continued to cascade from there, but not before CEO John Roth had sold his own stock options to net himself a profit of $86 million in 2000.

Broadcom’s story is a bit less harrowing. For one thing, the company is still in existence, which gives it a leg up on Nortel, Enron, and WorldCom. So it’s got that going for it. If you bought the stock when Smart Money recommended it, at $37.75 a share, you’d have lost money, but not your shirt. When Fortune recommended it, in August 2000, it was just about at its peak of $182 a share. The stock soldiers on, and is, like other big-cap technology stocks that dominated the market in the late 1990s, “dead money” for anyone stubborn enough to think they’re going to be made whole after all these years, though most of those investors are long gone.

Momentum Investing and Popular Media

The Smart Money and Fortune covers tap into the fascination that exists with stock picking that isn’t going to go away, no matter how bad a bear market comes to hammer the financially uneducated. Picking names out of a hat (which the Wall Street Journal famously did for years, looking at how a dartboard portfolio did against actual money managers) is interesting; it drives sales of magazines, and it provides investors with some kind of hope that they can accomplish the elusive goal that we fail at—to defeat the market’s average, to come out in front, by getting a few investments right. When you think about it, trying to come up with a bunch of stocks that will outperform isn’t much different than putting together your list of favorite sleepers in fantasy baseball or betting on which movie will make the most money in the summer movie season. But those bets don’t form the basis of your retirement account, and random picking of stocks can, and that’s a big mistake.

It gets truly dangerous when a particular stock or sector or market attracts the fascination of the popular media, which does tend to arrive at a story far after smart investors have already made a lot of money. Momentum drives this: Stocks that have been doing well for a period of months tend to continue to do well, and high-flying short-term gainers attract interest from less-informed investors in the marketplace, which helps stocks maintain an upward trend. An entire investing strategy, known as momentum investing, has flourished out of these tendencies; investors will follow stocks that show strong upward trends and jump on the bandwagon, hoping to get off before the stock inevitably falls. Eventually, such trends tend to stop, and more seasoned investors abandon a stock as it becomes overvalued. Without ready buyers to support a stock price, those who got in last are the ones who get burned, and more often than not those are individual investors who have invariably read an article on a fascinating new sector of the market that’s going to be bigger than anyone can imagine. The tendency for investors to follow the crowd was documented by three professors in the Financial Services Review in 2006. They wrote that “professional analysts are successful with the momentum strategy but the individual investors are not... momentum investing is not a viable strategy for individual investors.”4 The professors looked at individuals and professionals who participated in the WSJ Dartboard feature between 1999 and 2002, checking out how they did with individual purchases.

They found that both groups—individuals and professionals—focus on momentum stocks, those that are riding winning streaks, and many pick stocks that had already doubled in the last six months. The problem is that we are slower to catch on to such trends, and don’t end up grabbing those stocks until the upward trend is petering out. Is it so far-fetched to think that leading investment magazines don’t factor in momentum when coming up with stocks to buy and “forget about” for a decade? Looking back at the Smart Money list, Nortel had gained 250 percent in the last year as the authors had already noted. Broadcom’s returns were strong when Smart Money recommended it, and it was near a peak when Fortune suggested investors buy it. America Online and Citigroup were giant conglomerates that had been through substantial merger activity and were in the news on a daily basis.

There’s not one stock in these two groups that anyone could regard as an obscurity, which shows the power of momentum—investor interest begets interest begets interest. You can’t tell any rational person that recommending high-flying stocks like WorldCom, Enron, Lucent, or Inktomi represents the carefully considered advice of someone who spent days agonizing over such picks; more likely it was an attempt to latch onto something with momentum and pick out the names that seemed like they had the best chance of surviving another decade. And so for every instance in which you’re considering a purchase of a sector (since we’re not doing individual names here), an exchange-traded fund, or an investment in a particular country, you have to stop and think: Why am I buying this now? Am I getting in at a time before everyone else is? Or is it because I’ve just gotten this idea from a friend or a magazine noting great expectations? Have I done any research on this at all? Do I know anything about this industry?

The latter question—whether you know anything about the investment in question—is one that many people forgot during the tech bubble, and seemingly ignored during the financial bubble of the late 2000s as well. During this time, a frequent refrain from those who elected to largely stay away from the myriad tech companies springing up was this: “I don’t understand what they do.” That’s an understandable rule; it’s unwise to invest in businesses that one has a fundamental difficulty wrapping one’s arms around.

But this term did not just refer to the stated aims of these companies—providing “solutions” for complex problems that a veteran investor did not know existed—but the money-making prospects of those companies. The Internet space exploded in those years, and hundreds of companies issued public offerings of stock before having established a clear path to profitability. From there came the rationalizations. Since these companies didn’t make money, traditional ways of valuing them (by looking at their price and comparing it to expected earnings) were altered. Now it was acceptable to compare price to expected sales, even if profits weren’t part of the picture, or to compare to “eyeballs”—the number of people expected to view a particular application. And so the phrase, “I don’t understand what they do,” became shorthand for those people who saw these investments and didn’t see how, in any way, they could make money. The same started to be said of the banking stocks in the last part of the last decade, when the amount of leverage they had (that is, how much they had borrowed to make the money they were making) exceeded all reasonable boundaries and most of the unreasonable ones, too.

And yet it’s a truism that stocks, in environments such as this, can kick the butts of all comers for a short period of time. They tend to become losers and revert to the market over a three- and five-year period, but for a year or so, irrational bets can run higher and higher. Professionals tend to be the ones who garner more of an advantage from big bets like this. How did they do? Pros in the 2006 Financial Services Review study ended up with a market-adjusted return of 8.28 percent, while readers lost 3.78 percent. The difference seems to stem partially from professionals’ ability to herd in and out of stocks with positive and fading price momentum, something readers may be slower to get. They also may not be taking account of the same factors that professionals are, instead using strategies that rely “more exclusively on observed price increases. Such behavior may result in security selections that have experienced longer-term positive momentum and thus are closer to a reversal,” they write. Basically, regular investors are seeing prices go up, and want to get in on that, period, and don’t consider it beyond that.

Why do so many want to keep doing this? They want to get rich, quickly. That’s why they continue to want to search for what one-time Fidelity fund manager Peter Lynch coined “10-baggers,” stocks that absolutely explode, and can make an investor rich in a hurry (an early investor in Google, for instance). The Internet’s reach and the deals offered by discount brokerages (150 free trades now!) engender this kind of approach among people, to glom onto a fad and try to ride it higher. But bad investments can destroy a portfolio, and if individuals are looking for a quick answer, this is a terrible way to go, particularly because of the lack of accountability inherent when magazines publish such lists. (If you bought those stocks as recommended by Smart Money, did you sell them all at the right time, if possible? Probably not.)

That’s why those magazines have to be considered to be not much different than putting together lists of the best movies of the year, best books, top sporting events, or making prognostications about which football team will win the Super Bowl. It’s just that those lists are meant mostly as fodder for conversation. A big magazine cover that splashes “Our Oscar Picks!” is geared to pique interest on the part of people who love lists and have an interest in movies—which is a ton of people—but it cannot be confused with actionable intelligence, as it really only translates into a guideline for $20 bets in the company Academy Awards pool. Such a blasé interpretation of a magazine’s stock picks does not pass muster, not when people are constantly looking for an edge in the market, for that one idea that will push them out in front of everyone else.

And yet it continues. MoneySense, a Canadian personal finance Web site, in June 20095 decided to try its hand at ten stocks to pick for the coming decade, even acknowledging the dreadful record Fortune compiled by trying to put together a similar list. The MoneySense editors think they can succeed where Fortune failed; author Barbara Hawkins wonders what the Fortune editors “were smoking,” pointing out that Fortune picked a handful of very expensive stocks, did not diversify widely, and bet on industries that were currently dominating the market. This is all true. MoneySense’s own list intentionally looks for cheap companies, and so it found among them plane manufacturer Boeing and several other Dow industrials components—Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, and Wal-Mart. This is admittedly a better approach, but only time will tell whether these names, seemingly sound ideas in a world obsessed with safety in 2009-2010, will turn out prescient in a decade. But the record is not good, even if the magazine wants to have it both ways with a self-aware acknowledgement that “this is a dangerous exercise” by pointing out the unreliability of such predictions, and then making the predictions anyway. What will Hawkins say in ten years if it turns out badly? Slough it off as an exercise in futility that was already destined to flounder?

Buy GM, But Don’t Quote Us on That

The penchant for major investing publications to choose picks at the beginning of each year speaks, again, to the egalitarian nature of investing—that this is something everyone can practice, similar to journalism or home improvement, even if there are professionals who can do the job more effectively. It’s possible that the gamelike nature of these picks could be considered harmless if they weren’t followed, but they are weighed by investors making decisions about their money. What’s more problematic is when publications write articles on end about how prevailing trends in the market are soon to come to a close (particularly bullish trends). This is part of the more contrarian nature of journalism, although of course such articles come as a result of research, which involves talking to market strategists, none of whom has a better idea than any other whether the market is going to rise or fall in coming months, because it is impossible to determine on most levels. But the stock in trade among members of the financial media is a need to be skeptical of prevailing trends—countless stories have been written casting doubt on the strength of the market’s rally, or of its relative weakness. But the advice can be even more disastrous than a quixotic attempt to pick stocks for the next decade.

Case in point: Barron’s, the weekly investing magazine, put together a June 2, 2008, cover story titled “Buy GM,” referring to the beleaguered automotive company that was struggling to stay afloat.6 In the piece, the author said the stock seemed suited mostly for investors with an appetite for risk and a strong stomach. “Despite the misery that the car maker is experiencing and might endure for another 12 to 18 months, such a wager ultimately should pay off,” he wrote. The company was forced into bankruptcy early in 2009, and shareholders were wiped out.

Barron’s had a similar clunker of a recommendation less than two months later. On July 21, they quoted Mark Boyar of Boyar Investments saying financial stocks were a “once in a generation” opportunity.7 The article said “the brutal selloff in financial stocks—the worst for any major industry group since the technology bubble burst in 2000—could be over.” But the financial stocks continued to crater, with many imploding in September 2008. Those that disappeared after this article appeared included Washington Mutual, Merrill Lynch, and Lehman Brothers, which Barron’s noted was one of Boyar’s favorites. But Barron’s was confident in its prognosis, particularly with its assessment of regional banking institutions:

“Regional banks, which had been pummeled until a sharp rebound that started Wednesday, have deposit bases that are so valuable that buyers of banks historically have paid sizable premiums to get them. Deposits now are being accorded little or no value throughout the banking industry as many institutions, including SunTrust Banks (STI), Marshall & Ilsley (MI), Comerica (CMA), Wachovia (WB) and Zions Bancorporation (ZION) trade around their tangible book values—a conservative measure that excludes goodwill and other intangible assets.”

This conservative measure was so compelling that regional banks were mashed through the rest of 2008—the Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Regional Banking Index lost 22 percent that year, and when the lion’s share of the stock market posted a big turnaround in 2009, regional banks remained the worst performers as lending outside major institutions continued to stall, despite rock-bottom interest rates. That index dropped an additional 24 percent in 2009. Rising provisions to cover bad loans and expected deterioration in commercial real estate socked the regional commercial banks, and Marshall & Ilsley was the S&P’s worst performer for the year.

“How much did Barron’s cost you? $5? That’s probably about how much that advice is worth,” said Jeff Rubin of Birinyi Associates. “If something changes four or five months out there’s no guarantee you’ll have an update. They can’t go back and say, ‘sell this stock.’ That’s not what they do—their job is to sell advertising.”8

Barron’s endeavors to maintain a track record of how it is doing, listing all of the stocks they talked about positively or negatively in a particular year, and then averaging their performance against their varying benchmarks. For some reason, disaster picks like the June 2008 recommendation of General Motors are not included (this makes very little sense—the company’s cover story was titled “Buy GM”). The banks are also not included in the 2008 tally. Even so, the magazine’s track record is about as spotty as any other magazine. Its bullish picks in 2007 on average were down 23 percent through April 28, 2010, compared with a 15.8 percent loss for the average benchmark, according to Barron’s. They’re faring a bit better with 2008 picks, up 6 percent compared with a 0.02 percent loss for the benchmark, and the 2009 picks are up a handsome 41.9 percent, while the benchmarked average index is up just 30.7 percent. But, really, big deal—it’s not been anywhere close to long enough to really determine whether these picks worked.9

Barron’s also has a track record of its bearish picks, which an investor is presumably supposed to use to build short positions, but those picks also have a mixed record. Its 2009 bearish picks are up, on average, 17.8 percent, trailing the index average of 33.4 percent by a long shot; the bearish 2008 picks are up 7.2 percent, better than the 1 percent gain in the average index. The 2007 bearish picks have done terribly, falling 28.4 percent compared with a 13.4 percent drop in the index average, according to Barron’s data.

A long-standing feature in Barron’s was the roundtable, a year-end gathering of various investment managers to discuss picks for the coming year, and naturally, these ideas and predictions had a few gems hidden in them, but on the whole were rather suspect. Most of those who were summoned to participate in this roundtable, such as Ellen Harris or Joe Neff, appeared year after year. The roundtable continues to this day, with noted strategists Mario Gabelli, Bill Gross, and Abby Joseph Cohen of Goldman Sachs appearing in the vaunted articles. And this isn’t to say these strategists, taken together, do not have some good ideas, but in general, so many are so far from being on the market that it becomes pointless to continue to follow one personality.

The individual desire to break out of the pack has supported another class of those proffering investment advice that rank, in terms of cost, somewhere below hedge funds and brokerage research and above free online advice and magazines, and that’s the newsletter business. Mark Hulbert, editor of the Hulbert Financial Digest and a writer for MarketWatch.com and the New York Times, tracks the industry closely, and says he has a similar conclusion as many others—that most cannot beat the market, saying that it’s “a dismal industry, and there’s no evidence people are getting any better at it.”10 He estimates that there are anywhere from one to two million subscribers to newsletters, which would make the industry a $100 million to $200 million business, a lucrative one for those who attract a lot of subscribers as a result of their picks.

“Some have beaten the market over time, but the issue is not that: We know from the odds, one of five will beat the market over a period, but will the one of five in one period be the same that beat it in the previous period?” he asks. Hulbert looked at 200 different model portfolios covering the 2007-2009 bear market and found that while there were some that completely obliterated a passive index fund during the bear market (as the S&P 500 fell 50 percent), looking at the five-year period turned those results around. Just 11 of these model portfolios set up by newsletter writers made money during the bear market, which is great, but those same writers tended to lose money during the raging bull market that preceded the downturn. As a result, they averaged a gain of 1 percent annualized in the five-year period that ended when the bear ended, which isn’t so hot, especially as the index fund managed a 0.9 percent annualized gain.

Some news magazines, in addition to recommending stocks, try their hand at mutual fund ideas too—the shelves of newsstands are littered with monthly issues suggesting the “best funds to buy” at any given moment. Motley Fool, a popular Web site devoted to puncturing investment myths, put it best in 2000, saying cheekily that “scientific marketing surveys and focus group testing have determined that magazines with covers that read ‘Index Funds: Still The Best Choice!!!’ every single month really wouldn’t sell as well as magazines that promise ‘Our BRAND NEW 10 Best Mutual Funds To Buy RIGHT NOW!’ Sad, but true.”11

What’s worrisome—and true-blue journalists would deny this influence—is that many major publications write articles that mention funds that also happen to be heavy advertisers in those monthly and weekly tomes.

In a 2005 article, professors Jonathan Reuter and Eric Zitzewitz found a significant relationship between a fund company’s advertising expenditures and the chances that its funds will be recommended in leading personal finance magazines. “The robustness of the correlation leads us to conclude that the most plausible explanation is the causal one, namely, that personal finance publications bias their recommendations—either consciously or subconsciously—to favor advertisers,” they wrote.12

This allegation would not sit well with the editors of the major publications in question—Money magazine, Smart Money, and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance—but these magazines depend on advertising revenue from the mutual fund industry, which accounts for anywhere from 15 percent to nearly 30 percent of their advertising sales. (By contrast, Reuter and Zitzewitz found that the Wall Street Journal and New York Times derived about 4 percent and 1 percent, respectively, of their revenue from mutual fund industry ads.)

And the funds mentioned are benefiting as well. They found that positive articles in personal finance magazines and Consumer Reports are “associated with an economically significant seven to eight percent increase in fund size over the next 12 months, while a positive mention in the New York Times is associated with a 15 percent increase,” they wrote.

But as we see later, mutual fund investors fall far short of the returns advertised by the funds themselves, because we are buying those funds at exactly the wrong times—and we’re doing so because of mentions in the media, Morningstar’s vaunted star ratings system, and advertisements. And it’s not as if journalists follow these recommendations. Fortune itself admitted this with an article in 1999 entitled “Confessions of a Former Mutual Funds Reporter.” In this, the anonymous author says that reporters “seem delighted in dangerous sectors like technology,” but “by night, we invest in sensible index funds.” In sum, the reporter writes, “we were preaching buy-and-hold marriage while implicitly endorsing hot-fund promiscuity. The better we understood the industry, the sillier our stories seemed.13

There’s a reason for this. Publications need a story angle to make a story worthwhile; the media is supposed to inform and illuminate as well as broaden one’s knowledge. Writing about a topic or fund nobody knows about meets those criteria without a doubt—too bad it’s an awful method for stock picking.

This isn’t done out of a desire to curry favor with advertisers—most publications worth their salt head off their advertisers’ entreaties when it comes to coverage—but it does suggest that magazines aren’t looking much further than their own pages for ideas. As a result, it suggests, worryingly, that publications could be gearing their coverage around what will sell ads, or even worse, favorable coverage of mutual funds and investment advisories crops up as a result of heavy ad dollars. And the lack of knowledge that journalists have—the “Confessions” article says reporters were instructed to look to recent returns and hot sectors—makes advice that can be considered suspect at best even more conflicted, and therefore basically useless.

Ultimately, the better one understands this industry, the sillier all of the arguments for a particular purchase—be it a stock, commodity, ETF, or fund—seem, unless one is arguing in favor of the lowest-cost view. Americans in general tend to be slaves to bargains when it comes to electronics, apparel, home furnishings, automobiles, and even household goods. We buy massive jars of mayonnaise because it costs less per pound than the smaller, more sensibly sized jar. (Okay, that’s perhaps not the strongest example.) But when it comes to investments, there’s still a belief among many that the edge can only be found through additional expenditures—how else would the hedge fund industry, which charges a 2 percent management fee and 20 percent of the profits, manage to thrive as it has?

In retrospect, Business Week may have deserved more pillorying for the cover story it published in mid-1997. You’d think, 15 years after having been proved terribly wrong with an article about the death of the stock market, BW’s editors would have steered clear of another grand pronouncement. And yet on June 15, 1997, the magazine produced a piece called “How Long Can This Last?” which led off by asking, “could it get any better than this?” The magazine leaned on the then-popular “productivity miracle” argument, one that suggested further automation was making workers more productive, and therefore large companies more viable. This, would, in turn, lead to enhanced returns for years to come.14

Once again, Business Week had it largely incorrect, as the productivity thesis was largely disproved some years down the road, but this article is less egregious in that it does not attempt to convince readers of the inherent inferiority of equities (or their superiority, as it was in the late 1990s). It’s more a dissertation on the economic environment, not the market, so it’s less of a ringing endorsement of the folly of buying stocks based on magazine covers.

Talking Dartboards

If the stock market has been turned into a spectator sport as much as any other game—be it poker, baseball, or horse racing—then James Cramer, the former hedge fund manager who hosts a wildly successful program on CNBC, is sort of the Ryan Seacrest of the business media community, less good-looking, but nowhere near as bland. His appeal has a few aspects. For one, he’s exceedingly smart, and it’s hard not to see that. Second, his enthusiasm is unbridled, and investors pick up on that and convince themselves that they can make the kind of money that he made in the investing world for a number of years. Third, his approach is simple—the world is your oyster, buy whatever stocks you see fit (provided you do research, which he talks about in his book). Who wouldn’t find a “lightning round,” where Cramer opines on a handful of stocks in a few seconds that are thrown at him by readers, appealing? He spouts so much information in such a short period of time, it’s no wonder he was once referred to by Jon Stewart as a “dartboard that talks.” But there’s only one of him. To some extent—if you read his writings—he knows this, but on his show he’s doing his best to entertain. On some levels that’s a cop-out as people pay attention to his advice, and the stocks he picks tend to exhibit the same kind of “momentum effect” that stocks recommended by magazines tend to show.

A Northeastern University study in 2006 found that his picks tend to underperform the market, though a later, updated version of this study in 2009 showed better results. His portfolio gained 31.75 percent compared with a gain of about 18 percent for the S&P 500 for the period from July 2005 to December 2007.15

Good stuff, right? Now, of course, the cost of trading has to be taken into account. Assuming a flat rate of $9.99 per trade, that drops the portfolio’s performance to a gain of 22.42 percent, which is still ahead of the S&P’s passive 18.72 percent, according to Northeastern’s study. Now taxes have to be accounted for as well, and that would reduce the take further. Using certain other factors, such as investment risk, his portfolio fell short of the S&P 500 in 2006, but slightly outperformed in 2007. Furthermore, a two-year period is too small of a sample to really know whether a particular investor has real stock-picking skill. Cramer has said in the past—and in his book—that unless investors have the time to spend on researching stock positions, investing in this way is not a good idea. (There’s no doubt it works for him—it’s his lifeblood. But nobody else is Jim Cramer.)

Again, though, a similar conclusion can be reached when taking into account all of the factors involved in active trading and relying on the recommendations of others: That the returns advertised by Cramer, by mutual fund companies, or newsletters are not what they seem because the takeaway is that much less due to trading costs and taxes. Of course, that’s not what’s advertised, and media coverage of the Cramer study focused on the simple, easy to understand numbers that suggest he has some skill at picking stocks.

What’s inarguable, and more dangerous, is the influence Cramer (and other prominent analysts) have on stocks in general. The Northeastern paper finds that stocks mentioned as a “buy” by Cramer tend to get a bump of about 2 percent on the next day of trading after his “Mad Money” show airs the previous evening. Over time, the influence of those recommendations wanes, but this “Cramer Effect” is something that conforms to what others have written about the impact of analyst recommendations on stocks. CNBC anchor Maria Bartiromo for years began the morning with a litany of updated recommendations from various prominent Wall Street analysts, but those recommendations were then “quickly reflected in stock prices through client actions, before the mass investing public comes to know about the opinions (second-hand information). Thus, from the perspective of the average investor, analyst opinions qualify as second-hand information,” write the professors at Northeastern.

CNBC has become a bit smarter in recent years in the aftermath of the technology wreck. Investment gurus who appear on the show come armed with disclosures that appear onscreen, and they have to let viewers know whether they have long or short positions in the shares mentioned. But the focus is rarely on whether previous picks have worked out, and the horse-race nature of the coverage, namely, which stock is winning? Discussion of longer-term issues are reserved for the likes of Suze Orman, who, on a weekly basis, advises people to save their money and be smart, the kind of advice that doesn’t bring in viewers during the week. Her show is on Saturdays. She is a best-selling author and has tons of followers, so the market for sound, boring advice isn’t completely barren.

So turn off CNBC and try to stay focused on the long term. Rob Arnott, founder of Research Affiliates, which manages more than $50 billion in assets and is based in Newport Beach, California, tells a funny story about just what constitutes long term in the world of financial television. “I was being interviewed once on long-term forward looking returns, and was suggesting that [stocks] would be better than bonds, but not drastically, and the host said, ‘But look, the market has risen 140 points in the time we’ve been talking,’ and I had to resist bursting out laughing, because five minutes is not long term,” says Arnott. “It was quite a visceral example of the short-termism when people think about investing. It is treated as a sporting event and as a game and it does have enormous impact on people’s lives late in life.”16

Boiling It Down

• Take the financial press with a big, big spoonful of skepticism. The media’s track record is as bad as, or worse than, many professional investors.

• Don’t get caught up in the excitement offered by Jim Cramer. If you’re so determined to buy individual stocks, make sure you understand the perils—even the ones he points out—before proceeding.

• Before you make moves in your portfolio as a result of the excitement on television, make sure that what you’re about to do meets your long-term goals. Are you considering changes just because the market has gotten a bit jumpy and the press even more so? Take a deep breath.

Endnotes

1 “The Death of Equities: How Inflation Is Destroying the Stock Market,” Business Week, August 13, 1979.

2 David Rynecki, “10 Stocks to Last the Decade,” Fortune, August 14, 2000.

3 “10 Stocks for the Next Decade,” Smart Money, October 1999.

4 Glenn Pettengill, Susan Edwards, and Dennis Schmitt, “Is Momentum Investing a Viable Strategy for Individual Investors?” Financial Services Review 15 (2006), 181-197,

5 “Ten Stocks for the Next Ten Years,” MoneySense, http://www.moneysense.ca/2009/08/13/10-stocks-for-the-next-10-years/.

6 Vito Racanelli, “Buy GM: General Motors’ turnaround could accelerate in coming years, driving handsome gains for bold stockholders,” Barron’s, June 2, 2008.

7 Andrew Bary, “What to Bank On,” Barron’s, July 21, 2008.

8 Author interview.

9 Barron’s Online, http://online.barrons.com/stockpicks.

10 Author interview

11 The Motley Fool, http://www.fool.com/mutualfunds/indexfunds/indexfunds01.htm.

12 Jonathan Reuter and Eric Zitzewitz, “Do Ads Influence Editors? Advertising and Bias in the Financial Media,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, August 2005.

13 ”Confessions of a Former Mutual Fund Reporter,“ Fortune, April 1999.

14 Michael Mandel, Keith Naughton, Greg Burns, and Stephen Baker, “How Long Can This Last?,” Business Week, June 15, 1997.

15 Paul J. Bolster and Emery A. Trahan, “Investing in Mad Money: Price and Style effects,” Financial Services Review 18 (2009), 69-86.

16 Author interview.