7. Buying a Portfolio—And Selling It

“Regardless of the frequency of rebalancing, fidelity to assetallocation targets proves important as a means of risk control and return enhancement.”

David Swensen, head of Yale University’s endowment

The data previously cited about the long-term prowess of stocks does suggest that someone with an investment horizon of about 70 years (so if you’re about 13 years old and just got a bunch of bonds for your Bar Mitzvah, I’m talking to you) would do well to stick with indexing and leave it at that. But it’s not a realistic option for those looking at the last ten years of investment returns and seeing the paltry gains in all funds to say that leaving one’s money alone is enough to satisfy anyone. It’s simply human nature that a lost decade like this one makes an investor antsy, particularly with the limited number of offerings of indexes that are less sensitive to the impact of market capitalization. The 1990s were a time when anyone was a genius: Stock pickers did well, but passive investors who were content with indexes sure could look at several years of 20-percent-plus growth and not feel too upset about it.

But that hasn’t been the case for some time. “The fact is that investors are human beings and when you tell them they have less money than they had ten years ago they’re likely not to go for it,” said John Bollinger, president of Bollinger Capital and inventor of Bollinger Bands, a strategy that gauges market sentiment as to when to buy and sell shares. “When you inflation-adjust those numbers, they look terrible.”1

Bollinger and others suggest that some level of active management can be applied somehow to try to beat the market. Studies do prove this, even from the mutual fund company most well-known for indexing strategies—Vanguard of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. In fact, about 60 percent of Vanguard’s funds are actively managed. In a 2009 study, they found that in periods of relative calm—such as the 1990s—index funds have it all over those in the market trying to time the good and bad, with 69 percent of managers underperforming the Dow Jones Wilshire 5000 Index.2

But that flipped on its head in the 2000s. For the ten-year period ended in 2008, just 34 percent of managers underperformed indexes, while the rest managed to outperform. Part of this is because large-cap growth stocks, such as the Microsofts of the world, trailed badly in the last decade, and they make up the bulk of the market capitalization of the popular indexes such as the S&P 500 and the Wilshire 5000. (Again, another reason to try to find noncapitalization weighted indexes.) As a result, it was a time when active managers selecting small-cap value stocks could make greater headway. So where’s the problem? Once again, the issue is one of cost. If the average actively managed fund is costing an investor around 3 percentage points, that’s going to eat up returns, and suddenly an outperforming manager is struggling to keep up. “Most actively managed strategies fail because they charge too much,” said Fran Kinniry, head of Vanguard’s investment strategy group. “You probably find 60 to 65 percent can win, but when you look at after-fee they do not win.”3

Vanguard manages to combat this by keeping costs low, even in its actively managed funds, charging about two-tenths to one-half of a percentage point more than the company’s index funds. The average fund charges more than 1 percent in up-front fees, before trading costs are even accounted for. It may be that indexes aren’t the be-all end-all, but their cost structure usually sets them apart. What’s interesting is that Kinniry still notes that indexing is likely to come out ahead in the end over an actively managed portfolio unless the investor in question has the fortitude to get into the market at its most difficult moments, such as in February or March 2009. He notes that after hitting a 12-year-low on March 9, 2009, major averages gained 40 percent within the first 40 trading days of hitting that low, at a time when most investors were likely to be running away from the market. Domestic equity flows were negative in five of the six months prior to March 2009, according to the Investment Company Institute, which tracks mutual fund statistics. And March 2009 saw net outflows of $17.29 billion from U.S. equity funds, according to the ICI. Flows into equity funds only started to pick up a bit more in the late first quarter of 2010, almost a year after the rally had begun and those in the market had watched major averages rise by 70 percent.

It suggests again that the retail investor tends to be poor at timing the market, as this was the most opportune time for an investor to be buying, once again, at the time of greatest pain. Those in index funds could be assured that they were at least in the market.

So the performance of actively managed funds means that in an environment of uncertainty likely to persist for another several years, it’s best to go in that direction, right? The trouble lies in two places: the disclosed fees, which are easy to figure out, and the other fees—trading costs. As time has worn on in the stock market, turnover has increased dramatically; the average mutual fund now turns over most of its portfolio within a year rather than holding for several years, and this is a major bite into costs—returns have to justify the additional activity.

It’s relatively easy to document this sort of thing when it comes to retail investors. As mentioned earlier, Terrence Odean and Brad Barber found how the average household was outperforming the market between 1991 and 1996, but fell short once trading costs and commissions were added in.

This sort of thing hadn’t been effectively studied in mutual funds until very recently, but a trio of professors—Roger Edelen of Echo Investment Advisors, Richard Evans of Boston College, and Gregory Kadlec of Virginia Tech—managed the trick in the last couple of years as well, publishing a study in 2007 that showed how trading costs are eating up returns for professionals also.

While their estimates of trading costs can be disputed, they also found that most mutual funds are killing themselves with those costs, which were even worse than up-front fees. In some instances, the expense ratio still outweighed the trading cost: Funds investing primarily in large-cap stocks sported a mean expense ratio of 1.12 percent, while the estimated annual trading costs were 0.77 percent.4

But when looking at funds concentrated on small-cap investments, things get a lot worse: Expense ratios were about 1.34 percent, but the estimated trading costs were a ridiculous 2.85 percent. So that’s more than four percentage points of outperformance needed just to surpass the market average, and as Vanguard’s data shows, there aren’t a lot of managers that can achieve this.

The managers who do the worst, interestingly enough, are the largest funds. What’s so distressing about this is that they’re the ones more likely to attract the bulk of investors, either through 401(k) plans or because of reputation. Trading costs increase as the fund grows, according to Evans of Boston College. “If you have a million dollars under management and you’re trading 100 percent of your portfolio, well, a million bucks seems like a lot to me but in terms of moving the price, the impact in trading is not very large,” said Evans. “Once I get to a billion dollars my trades are going to move the market, so as I start to get out of a position you’re driving the price down and when you get in, you’re driving the price way up.”5

As each successive trade pushes a stock higher or lower, it increases those costs for that particular fund. It’s akin to turning an aircraft carrier—it’s going to make some waves. The largest funds trade less than smaller ones—with trading volume of about 147 percent of their fund in a year, compared with about 188 percent for smaller funds—but the cost per trade is much larger, and so the cost comes out the same—about 1.44 percentage points of annual trading costs per year. All of this work just to fall short of major averages.

Rebalancing—Your Best Friend

By now we have established that mutual fund managers are more often than not going to fail to outperform the broader index, usually because costs will eat up their profits. So it leaves an investor in the position of Newman in the “Seinfeld” episode, trying to find the magic formula that would allow him to ship thousands of recyclable bottles to Michigan (where bottle deposits are 10 cents, rather than 5 cents in most other states) without incurring the heavy gasoline costs that would destroy his returns. It’s about as easily solved, too, and you’re not saddled with the advice of the hapless Cosmo Kramer.

Trading more frequently doesn’t seem to be the answer, either. So beginning with an index fund as one’s stock allocation makes the most sense due to the favorable cost factors. The rest of one’s portfolio will be allocated to bonds, cash, commodities, real estate, bank loans, or a few other assets discussed later. The question then becomes, what is the proper level of active management for investors interested in trying to maximize returns?

This section takes you through the most passive—simple rebalancing, done automatically once a year—through more active levels of management that include chart-based market timing and those who are attempting to mimic the portfolios of people who actually do seem to have a knack for being good stock pickers (and there really aren’t too many of these). What we’ll see is that there are many folks who aren’t giving up—who believe there’s a way to consistently come out ahead of the market over a long period of time, a place where many have tried and failed. For my part, I tend to stick to the idea that simple rebalancing and occasional selling of certain highly valued assets is the best, most prudent approach, without getting particularly fancy, and then of course shifting your allocation when you’ve got the kind of time horizon that demands you get more conservative.

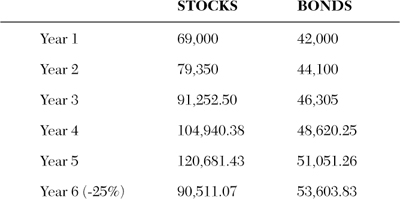

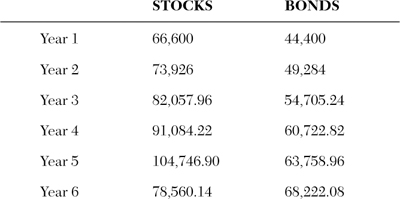

The argument for rebalancing a portfolio is simple: If an investor believes their level of risk appetite and their goals match up best with, say, dividing investments into 60 percent stock and 40 percent bonds, after a while, given varying returns for these investments, stocks or bonds are going to start to dominate the fund more. A $100,000 investment split in this way that posts a 20 percent return for stocks and five percent for bonds is going to rise to $72,000 in stocks and $42,000 in bonds. That investment has grown to $114,000, and the stock portion is now 63 percent of the portfolio, and that’s more than an investor wants. A bit of selling once a year will bring that back in line, and should the more expensive asset—likely to be the stock market—experience a pullback, it will not be felt as much in one’s holdings because of the previous rebalancing effort. (See box for explanation.)

David Swensen, the investment strategist who oversees investing for Yale University’s endowment, is a big proponent of rebalancing. An article he wrote noted that in fiscal 2003, Yale “executed approximately $3.8 billion in rebalancing trades, roughly evenly split between purchases and sales. Net profit from rebalancing amounted to approximately $26 million, representing a 1.6 percent incremental return on the $1.6 billion domestic equity portfolio.”6

There are still concerns with this approach, particularly when rebalancing is used frequently, as it can come back to hit individual investors. In a market that continues to trend upward consistently, or downward consistently, rebalancing trades can reduce risk, but they can hurt returns, because investors will be consistently reducing their holdings in the investment that is doing well, and because there’s a cost to these trades (further behooving you to find the lowest-cost option possible, or taking advantage of a discount brokerage’s offer of dozens of free trades by parceling them out as infrequently as possible). Still, during the bull run of the 1990s, an investor would be shedding the very asset that was outperforming in favor of the more sluggish returns of bonds; during bear markets, investors would be doubling down on stocks amid ugly slumps. “The U.S. stock market’s steady upward surge during the mid- to late-1990s was an example of a trending market. Rebalancing produced lower returns than a portfolio that was never rebalanced,” wrote analysts at Vanguard in a recent study.7

The 1990s market may, however, have been an aberration. Stocks moved consistently higher for most of that decade, exploding into the end of a multiyear run with several years of 20-plus percent in returns. The 1960s and 1970s were nowhere near as kind, and of course, this most recent decade hasn’t been friendly to those who let it ride, either.

Overall, it seems there’s a middle ground for rebalancing. Quarterly rebalancing of a portfolio, assuming a five percent deviation from your targeted allocation (say, 60 percent equities, 40 percent bonds), gives you a disciplined schedule to work from, but doesn’t incur unnecessary trading if your assets haven’t returned enough to warrant the rebalancing. From 1960 to 2003, quarterly rebalancing produced a return of 9.669 percent annually, slightly better than monthly or annual rebalancing, according to Vanguard. Such portfolios were also a bit less volatile than those rebalanced just one time a year, and produced better returns than the monthly rebalancing schedule.

If anything, the data supports limited efforts to shift one’s portfolio so it reflects the intended allocation, but preferably with a high bar so excessive trading costs are not incurred. Swensen maintains that this is meant to be a way to impose discipline. For many of you, this kind of approach can serve as a perfect structure for reevaluating your investments or making simple changes—you know you’re going to look at it quarterly, but no more than that and you’re going to have to see significant movement to justify changing things. But it also means you’re giving yourself a chance to see how things are going instead of forgetting about it and only taking a gander at your portfolio when things are going haywire, and everything’s been lost. Make no mistake—simple rebalancing will not prevent or avoid bear markets. But a portfolio that’s constantly shifting assets away from those that have outperformed is more protected than that of one that has never done such a thing.

Timing the Market

The once-a-year “set it and forget it” style of rebalancing has its merits because it does not require the investor in question to make judgments about the market. It assumes a certain risk tolerance and sticks with that regardless of the environment. Some managers advocate a more opportunistic approach to rebalancing, the kind of thing Swensen of the Yale endowment seems to actively do.

This strategy has a bad name, though—market timing. And the reason it has such a horrific reputation is again more a result of practice than it is theory: It’s because so many investors are just awful at executing it. Just as investors are more likely to buy mutual funds when they reach their peak in terms of investing prowess (and thus dooming themselves to inevitable subpar returns later on), they also have very poor judgment when it comes to effectively buying and selling the market.

Naturally many professionals advocate such an approach, seeing it as the key to outperformance in their portfolios. In see-saw times, it’s hard to justify sitting back passively, as Vitaliy Katsenelson, president of Investment Management Associates Inc. in Denver, Colorado, puts it: “You have to be proactive in buying and selling.” He, of course, actively manages portfolios for his clients, and detractors of the argument suggest that most fund managers are unable to add excess return because of costs and the inability to maintain an edge over a long period of time.8

From a theoretical level, it makes sense that there are some sectors and some asset classes that outperform markets at different times in the business cycle. Researchers from Massey University took a look at the idea of buying certain sectors at certain times, but found the simpler strategy of continuously buying stocks—moving out of stocks only during the early portion of the recession—is superior to most other strategies that involve buying stocks more sensitive to the economy (semiconductors, construction, and equipment companies) when demand is rising, and moving to things that are always needed when demand is falling (utilities, health care, toothpaste). They found that such a strategy—where investors buy stocks through the early, middle, and late parts of an expansion, shift to cash for the early recession, and then back into stocks late in a recession, would outdo the market by an average 7 percent.

Mike Trovato, product manager at Pacific Investment Management Co. Inc., argued for a similar approach in a November 2009 commentary. He noted that essentially, investors should feel free to invest in riskier assets during the expansion and late part of a recession, shifting to Treasury securities during the early part of a recession. In the early and middle part of the expansions that took place between 1988 and 2008, emerging market debt was the best investing vehicle for returns, outdoing high-yield debt, equities, convertible bonds, and Treasury securities. Late-expansion, stocks were the best performers.9 But at the onset of the recession, it was time to get into the government bond market and leave everything else behind. On average, Treasuries produced an average return during those periods of 10.62 percent, while all other asset classes lost money during that period. Treasuries continued to do well through the late part of the recession, but now they were once again bested by high yield debt and other kinds of debt as investors turned to the idea of greater risk.

What’s the problem with all of this as a strategy? It’s predicated on your understanding that a recession has arrived, and in December 2007, when the recession started, very few of us got that idea, particularly as markets had peaked just two months earlier. In fact, most were convinced the market’s problems were minor, confined to subprime mortgage loans and bad debts in various economies that had overborrowed when their currencies were highly valued. Of course, this proved to be a disastrous assumption, and every asset class was roundly kicked in the rear, with the exception of (you guessed it) the Treasury market, which rallied as bonds hit record lows.

But more and more professional investors are heeding the lessons learned in 2008 and 2009, and believing somehow, they have to take a different approach. They’re instead taking the notion of shifting assets from high-performing classes to lower-performing ones to a more granular level. This emerging approach to portfolio management is known as “tactical asset allocation,” and maybe that’s a fancy way of saying “market timing,” but top professionals argue that reallocation based on set parameters, be it relative strength of a particular stock sector, or certain technical patterns, can save investors headaches. “A total of 99.9 percent of the industry is very negative on market timing and stock picking, and research shows that both people and professionals are consistently horrendous at it,” said Mebane Faber, co-founder and portfolio manager at Cambria Investment Management in Los Angeles.10

But Faber notes that in the 20th century, all of the G-7 economies—the largest world economies including the U.S., U.K., Japan, and Germany—saw their stock markets experience a period where they lost 75 percent of their value. And in such a case, an investor then needs a 300 percent gain just to get back to even! That’s a 10 percent return over the next 15 years—and many people don’t have a 15-year horizon, such as retirees who were expecting a nest egg until they ran into the 2007-2008 debacle in the markets. And plenty of markets don’t give you 10 percent a year for 15 years—invariably there will be a correction in that time that makes breaking even from horrific losses more difficult. It behooves people to try to avoid such fallow periods, and it makes it easier to do so when you’re not invested in individual stocks that can completely disappear, but instead in a number of asset classes with an eye to flexibility.

He advocates a relatively simple approach to market timing. It involves looking at one’s assets at the end of every month and determining whether stocks have risen above the ten-month moving average or fallen below it. Moving averages are calculated by taking the closing prices in a particular average over a period of time, and adjusting that every day or week or month to take into account each new piece of information as time passes. They’re used frequently as a way to gauge trends in certain markets. When an index falls below a certain moving average it is taken as a bad sign. So, if the S&P 500 is trading higher than its ten-month moving average (the average closing price over the past ten months), stay invested in stocks. When it falls below this level, it’s time to sell and go into cash or some similar equivalent. And then, once the market has again moved above the 200-day moving average, it’s time to buy.

This does appear to produce better returns: Between 1900 and 2008, the S&P 500 posted an average annual return of 9.21 percent, with nearly 18 percent volatility (the percentage an index may be expected to move up or down in one year). But a timing approach boosts that return to 10.45 percent, and reduces volatility to about 12 percent. Such an approach would have gotten investors out of the market within the long bear market of the 1930s, and the decline would have been reduced to about 42 percent from nearly 84 percent.

Bull markets, similarly, would have not been as fruitful for the market timing investor—investors would have gotten out before the market peak. Faber’s data shows that investors in the 1940s and 1950s would have trailed the market averages due to the strategy’s penchant for pulling out of stocks at what appears to be a time of overvaluation—but one in which stocks continue to gain strength. The 1990s are similar: This roaring period would have been somewhat missed in Faber’s approach—gaining about 13 percent on an annual basis, compared with more than 18 percent for those who simply held the market.

On the upside, investors would have stayed out of shares after the inevitable decline—the 2008 fall of 37 percent in the S&P 500 would have not fazed someone subscribing to Faber’s system, as that investor would have posted a 1.3 percent positive gain for the year, having jumped out of stocks on the last day of 2007 in favor of Treasury bills.

So when does this approach really shine? In see-saw periods, such as the 1970s and 2000s—periods that included terrible bear markets and rousing bull markets, sometimes all within a year. The average annual return during the Disco Era was 5.88 percent, but timing the market boosts that to 8.4 percent. And the index lost 3.6 percent, on average, between 2000 and 2008, while the more nimble investor looking at the moving average gained 6.3 percent.

The method, at least according to Faber’s data, works for other asset classes as well—investors would have boosted returns in foreign stocks to about 11 percent from 9 percent between 1973 and 2008, and the same goes for someone in global commodities indexes, where returns improved to 11.2 percent from 8.7 percent, again reducing volatility, and real estate investment trusts, which improved to 11.7 percent from 8.5 percent. (The difference for long-term Treasury debt is miniscule, by contrast.)

This system isn’t fool-proof, obviously. Commissions, fees, and taxes come into play, particularly as investors are looking at making three or four trades a year from one asset to Treasury bills and back again, according to Faber, in a paper he wrote for the Journal of Wealth Management.11 Obviously, using index funds and ETFs will keep costs low, and commissions should remain low with a limited number of trades, particularly in an era where ETFs are tradable without a commission. Taxes are likely to impose a bigger bite on investors, which makes implementing such a strategy in taxable accounts potentially cost-prohibitive. A tax-free account such as a 401(k) is a more ideal place for such a strategy.

Right now, the chief problem folks like Faber face is convincing clients that tactical asset allocation, or as it is more problematically known, market timing, makes any kind of sense at all. Investors have been schooled in buying and holding investments, frightened—for good reason—that they’ll make decisions to alter the mix of their investments at all the wrong times. Furthermore, this system has only been back-tested, and it remains to be seen whether such a strategy will withstand periods where the market teeter-totters for a long time, giving off false signals on getting in or out of the market, or if it goes into another extended run similar to the 1982-2000 period that demands investors remain invested at all times.

However, the principle behind it—that investors shouldn’t blindly assume that the markets will cure all ills over a long period of time—is a sound premise, and it’s not been one that you and I have been able to accept more readily in recent years. After all, for so long, stocks continued to go up and up, and we allowed ourselves to assign blame for the brief recession in 2000-2001 to overvalued technology companies and horrific terrorist attacks, thus rationalizing its existence away. Getting back on the “all stock” horse was easy. That’s harder to say now, with the Dow in 2010 still struggling to stay above the 10,000 mark, a level it first surpassed more than 12 years previous.

Now, however, you can sense a sea change. Many investors are piling their assets into bonds, regardless of the market’s fantastic rally that started in March 2009. That’s because the idea of another ten years of volatile markets that essentially go nowhere isn’t going to make anyone happy. “It’s self-preservation,” one UBS Securities advisor told Registered Rep. magazine in August 2009. “I have to make my clients money no matter what kind of market we’re in or I’m out of business.”12 (Disclosure: I worked at this magazine between 2001 and 2005.)

Implementing an effective strategy that shifts money from one asset to another based on market levels isn’t easy, however. “The key is to have the courage to sell what everyone loves and thinks will perform brilliantly and buy what everyone fears and thinks is headed for oblivion,” said Rob Arnott, who uses tactical asset allocation in his portfolios, among other management approaches. Without that, he says, “you’re better off with simple rebalancing.”

The approach has its detractors. Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, said in the Registered Rep. article that professionals are no better, as “most managers tend to be most bullish at the top, bearish at the bottom.” A trio of professors published a paper confirming this in 2007: They noted that whatever the benefits of having a financial advisor were, superior skills at timing the market was not one of them, and in fact, their picks tended to underperform the market, even before fees were included in the mix. “We find no evidence that, in aggregate, brokers provide superior asset allocation advice that helps their investors time the market,” wrote Professors Daniel Bergstresser, John Chalmers, and Peter Tufano. “While we cannot observe the asset allocation skills of individual brokers nor the degree to which brokers fashion customized portfolios for their clients, the aggregate asset allocations show no advantages among the broker-sold funds.”13 Perhaps not wanting to be too harsh, the trio conceded that other benefits—helping people apply a savings discipline, realizing tax benefits for clients—might offset some of the costs of the assets purchased (and the up-front fee demanded by advisors), but the hard evidence that relates to costs shows that advisors aren’t any better at this, and they add in a middle man that charges more money.

Fran Kinniry of Vanguard, meanwhile, said the firm manages funds in a tactical manner as well, although judging by the public speeches from Vanguard’s storied founder John Bogle, one wouldn’t know they had anything subject to active management. In reality, more than half of the firm’s assets are being managed as such, and Kinniry still says their belief is that “most actively managed strategies fail because they charge too much.” Vanguard’s actively managed funds have a lower expense ratio, which makes outperformance more likely, but certainly not a slam-dunk.

Nevertheless, Kinniry and others recognize that the Holy Grail—outperformance—beckons many an investor. Few have positive expectations for the investing environment in coming years, something we’ll discuss in a forthcoming chapter, and because of that, a raging bull market similar to the 1990 to 1999 period, or the prolonged steadiness of the 1980s/1990s seems unlikely, even though investors have already experienced this for the last decade. And with that expectation comes the desire to avoid getting caught in a trap where passive investments lead investors down the wrong path if there’s a way—some kind of way—to avoid that.

The Buffett Way

The search for the better mousetrap has motivated many, including Mazin Jadallah, chief executive officer of investment research service AlphaClone, which he co-founded with Cambria’s Mebane Faber. Jadallah describes himself as a “very frustrated retail investor,” particularly in light of his impressive background: an MBA from Rollins College, stints at Open TV and Time Warner in analysis and corporate development. But managing his portfolio just wasn’t working out.

“I have a high opinion of myself,” he said. “I’ve got an MBA in finance, I worked at Time Warner for (former CEO) Dick Parsons, and I’ve done strategy and M&A and corporate development work. I know what the value of our company is, but I couldn’t pick a stock to save my life. Is it asymmetry? Is it that I don’t have time or the money to do the kind of tight analysis to pick winners? I think for a whole host of reasons, most people are not very good at picking stocks.”14

However, he and Faber weren’t convinced there was nobody out there who didn’t outperform markets consistently. If anything, there was Warren Buffett, and while the famed CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is not constrained by the parameters of a mutual fund, Jadallah felt there had to be some way to track Mr. Buffett, and that there had to be others who had demonstrated consistent prowess in picking equities that would do better than the rest of the market. Among those he named were Greenlight Capital’s David Einhorn, Chris Davis of Davis Advisors, Daniel Loeb of Third Point LLC, and the various people who were schooled under Tiger Management’s Julian Robertson.

Of course, access to these hedge fund managers is limited to those with connections and a lot of money, but AlphaClone is trying another method—searching through 13-F filings, regular submissions on holdings by hedge fund managers to the Securities and Exchange Commission—and combing through them for data on holdings of these big investors. The investment research firm then constructs portfolios based on the most current information about these holdings. Using their best information they’ve found that these portfolios, when back-tested, can outperform dramatically when compared with the market. And instead of following just one manager, like Buffett, a subscriber can follow several managers at once to reduce the risk of one firm’s blow-up (after all, a number of prominent hedge funds melted down during the 2008-2009 disaster, and nobody would have been all that thrilled with mimicking the destructive portfolio that Long-Term Capital Management saw whittled away to nothing in 1997).

Jadallah says the company doesn’t track underperformers—it would be pointless to create clones that match lousy managers. And some hedge funds have proven more problematic than others to create clones out of because of massive levels of trading in these funds, heavy usage of derivatives, certain types of short sales, arbitrage strategies, and other tricks sophisticated managers use to hide their positions. Some hedge funds, such as Renaissance Capital or SAC Capital, have generally poor performing clones because of this. “That doesn’t mean (SAC) doesn’t do well,” Jadallah says. “But our whole point is from a retail investor’s perspective: Any investor who is not in the SAC fund doesn’t pay attention to their 13-F disclosures or stock moves—the back-tests show the clone wouldn’t do well.”

There are other concerns as well: AlphaClone, which went live in December 2008, doesn’t have access to the manager itself, and a 45-day waiting period to file with regulators after the end of a quarter is the equivalent of delivering e-mail by Pony Express—careers have been lost on stocks held for an extra week, never mind a month-and-a-half. By then, the hedge fund manager could have sold that position and every other holding in their fund and gone in an entirely different direction.

It’s easy to see how AlphaClone could gain popularity with the legion of investors looking for a shorthand way to invest the way pros do (the basic cost of membership is a mere $30 a month, with plans to charge as much as $100 a month, according to Jadallah). It’s because we’re willing to move the earth to find that Holy Grail, that person who will outperform all others for long periods of time, and not just what seem like extended lucky runs of six to eight years,

It’s a task that a man named Ken Kam has been trying to accomplish for most of the last decade. Kam is the founder of Marketocracy, a Web-based product that has tracked portfolios for most of the decade, not from the Buffett types, but regular people who manage their own money and who contribute their picks to Marketocracy’s data. Currently, there are more than 80,000 people managing more than 100,000 model portfolios from more than 130 countries around the world on the Web site.

Kam’s firm has found that certain people are better at picking stocks and making money than others. Unlike those who believe that ultimately, trying to beat the market is a loser’s game, where eventually everyone falls to the middle, Kam is of the belief that money can be made consistently. And individuals who think they have the chops can sign up on their site (for free) to run model portfolios. (Premium membership adds access to advanced portfolio management tools and reports on what others are doing.)

These are model portfolios—signing up gives an investor a fictional $1 million to invest, and each member can register up to ten funds. The company publishes rankings of its best performers on its site—as of March 31, 2010, the leader over the last five years was a man named Mike Koza, an engineer by trade who over five years has an annualized return of 38.6 percent.15 A few others are listed on the site, with their biographies, and then others with top performing funds include the likes of people who go by “bravedave” or “the_barnacle,” which are not the names of fund managers one is going to find in a mutual fund prospectus any time soon. Nonetheless, they do suggest that those with a sufficient amount of time can do well, although once again, these portfolios are models, and the company’s disclaimer notes that “since the trades have not actually been executed, the results may under- or over-compensate for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as the effect of limited trading liquidity.”

Kam recognizes that there are no certainties in the business. Bill Miller is the toast of Wall Street for more than a decade, and then people don’t consider him fit to wipe their shoes. Those in the market are, of course, only as good as their next call. But Kam is still not convinced that the “mechanistic” approach, one that advocates indexing, rebalancing, and not much more, is the way to go.

“People have tried to take all of the judgment out of it, and I don’t think it’s possible to take all of the judgment out of it,” he said. “In the end, it comes down to either you need to develop judgment and know what kinds of judgments you’re good at, or find people who have track records that are better than yours and those are the people you should delegate to.” He notes that the market’s 40 percent drop in 2008-2009 was not something many could foresee, and even fewer were counting on, and unless the investor in question is within shouting distance of their senior prom, the long-term average is of little comfort. “People can’t afford to have the next ten years be like the last ten,” he said.16

The most disconcerting aspect of that statement? The next ten years may, indeed, be similar to the past ten, particularly if you’re primarily invested in the U.S. It’s why Kam stays in business. It’s why people are going to continue to eschew the idea that they have to merely put money into an index fund and leave it there. It’s our nature to strive for something more than average.

But that’s where it’s time to go the other direction. It’s possible to set up a portfolio at an extremely low cost these days and maintain it through the use of a suddenly popular product called exchange-traded funds. They provide the possibility of diversification and tax efficiency and the freedom to trade at any point. Now that’s a dangerous proposition for some—those of you who have been buying and selling stocks without regard to cost could easily make the same mistake with these products.

Boiling It Down

• Rebalancing has many benefits. It forces discipline as you look at your portfolio a few times a year, and it imposes a strategy that forces you to stick to certain targets instead of letting your emotions get in the way.

• Try to find the lowest-cost solution possible. Some funds do not allow for short-term trading, that is, within 90 days of a purchase. Or use discount brokerages as a method of shifting assets if necessary—remember, the more you trade, the more it costs you.

• Keep it simple: If you do not feel comfortable doing anything more than resetting your assets once a year, stick with that. Even simple rebalancing will help reduce your portfolio’s volatility.

• For the more experienced, rebalancing quarterly, or in line with the strategy of certain professionals, may be advisable, but keep the portion used to rebalance based on someone’s recommendations limited to only a portion of your portfolio.

Endnotes

1 Author interview.

2 Christopher Phillips and Francis Kinniry, “The Active-Passive Debate: Market Cyclicality and Leadership Volatility,” Vanguard Investment Counseling and Research, 2009.

3 Author interview.

4 Roger Edelen, Richard Evans, and Gregory Kadlec, “Scale Effects in Mutual Fund Performance: The Role of Trading Costs,” working paper, March 17, 2007.

5 Author interview.

6 Wealth Management Exchange, http://www.wealthmanagementexchange.com/articles/14/1/Managing-Your-Portfolio-Frequent-Rebalancing-Helps-Maintain-Allocation-Targets-/Page1.html.

7 Yesim Tokat, “Portfolio Rebalancing in Theory and Practice,” Vanguard Investment Counseling and Research, May 2007.

8 Author interview.

9 Marc J. Trovato, “Diversified Investment Solutions for the New Normal,” PIMCO, http://www.pimco.com/LeftNav/Viewpoints/2009/Diversified+Investment+Solutions+by+Trovato+Nov+2009.htm.

10 Author interview.

11 Mebane T. Faber, “A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation,” The Journal of Wealth Management, Spring 2007, updated February 2009.

12 John Churchill, “Market Timing: Fool’s Errand or Prudent Strategy?”, Registered Rep., August 2009, http://registeredrep.com/investing/finance-market-timing-0801/index.html.

13 Daniel Bergstresser, John Chalmers, and Peter Tufano, “Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Brokers in the Mutual Fund Industry,” September 26, 2007, published by the Oxford University Press, The Review of Financial Studies.

14 Author interview.

15 Marketocracy.com/analysts/topranked.html.

16 Author interview.