11. The Outlook for the Future

“The last ten years have produced very bad returns...but you talk to people and they still think equities are wonderful. I don’t dispute it—I think equities are a good long-term investment. What worries me in the short-run is how unanimous that vision is.”

Andrew Smithers, president, Smithers & Co., London, January 2010

To invest in the success of Corporate America over the past 35 years, investors would have done well by buying and holding an S&P 500 index fund. Warren Buffett said as much in his 2004 letter to clients.

But that simple strategy may not be the winning formula for the next 35 years. There are legitimate concerns about what the next generation of growth will look like for U.S. markets and markets around the globe. Massive imbalances brought on by large debt issuance have created problems for several large societies, but most notably the U.S. and Japan, which in 2010 were still the two largest economies in the world. It is, therefore, legitimate to ask whether the U.S. will be the equivalent of a “growth stock” in the next few decades, or whether it is a busted growth stock—something that retains a high value largely on reputation despite mediocre economic demand for a number of years.

For a look at what may happen in the next several years, let’s look at the 1966 to 1982 period, a time that was also marked by lackluster economic activity. Wage growth was reasonably strong, but rising inflation and a crushing bubble in energy prices eroded a lot of those gains. The U.S. was taken off the gold standard while inflation leaked into the economy due to a series of poor decisions by ineffectual Federal Reserve chairmen.

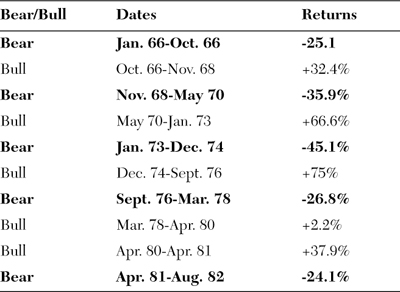

This 1966-1982 period was a great one in the market if an investor knew when to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em, as Kenny Rogers would say. Stocks experienced a handful of sharp rallies in this period of time, offset by a number of ugly downturns. For the index investor, it was a rough period, with the S&P and Dow in 1982 roughly in the same place as in 1966. Between January 1966 and August 1982, when the market turned definitively higher, there were four big, solid bull markets, five ugly bear markets, and one lackluster trading range that lasted about two years (see Table 11.1).

Table 11.1. Bull and Bear Markets, 1966 to 1982

Looking at this roller coaster 16 years, there are clear time periods investors should have avoided, and several periods investors would have laughed all the way to the bank. These took place amid long recessions, the energy crisis of the late 1970s, and America’s worst bout of inflation in more than a century.

The last decade, 2000-2010, has been similar, although the runs have been a bit less frequent. Stocks were terrible between the 2000 peak and the trough reached in mid-2003, but then went on a relatively steady four-year run that took shares to new records in late 2007. After that, it’s been a roller coaster more easily identified with the 1970s, as shares lost half of their value between October 2007 and March 2009, when the S&P 500 hit a 12-year-low, and then gained back more than 70 percent through the end of March 2010. Many a smart investor missed a good lot of that period—the Investment Company Institute shows net outflows from domestic equity funds in every month from August 2009 to December 2009. Meanwhile, if you stuck it out with a buy-and-hold strategy for the bulk of the decade, you’re still underwater with a diminished time horizon to make up for those losses.

Expectations in coming years suggest a need to be nimble. The massive unwind of debt on corporate balance sheets and the time it will take for the restoration of growth engines in the U.S. economy mean that the market will experience several more “boom-and-bust” episodes. The stock market will be a wild, unpredictable place as a result.

For those who suggest that this cycle—the period of stagnating in returns—is bound to come to a close soon anyway because the market has already experienced nine flat years, should reconsider that optimistic view. If the market does follow a similar cycle as last time, then the next long bull run should commence late in the decade after a few more years of stagnation. Again, for a 12-year-old, this is fine, but for those rapidly closing in on retirement, or currently in the midst of their best years for investing, waiting it out isn’t a sound idea. After the stock market peaked in 1929, it underwent a 25-year period of flat markets before it started to trend higher in the mid-1950s. And the sharp gains prior to this only lasted for a short period of time, from about 1921 to 1929—before that, the market endured about 21 years of Nowheresville as well.

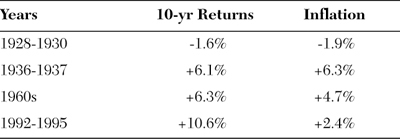

While stocks may have seemed cheap in February 2009, the 60 percent rally meant stocks weren’t all that cheap anymore, according to Research Affiliates Inc. With stocks at a price-to-earnings ratio of 20 to 22 times trailing 12-month earnings, they were at levels that, when reached in the past, generally translated to lackluster returns for a period of years. Table 11.2 outlines what happened in the ten-year periods after stocks reached such P/E ratios.

Table 11.2. High P/E Ratios Don’t Translate to Strong Markets

Source: Research Affiliates1

Of the four periods, the ten-year period after the mid-1990s was obviously an exception. The first one is the Depression, while the second two produce decent returns that are eaten up by higher than usual inflation. It’s hard right now to fathom another Depression, although the economic recovery in mid-2010 has been flagging. We’re more likely to see an overheat in asset prices than some kind of collapse as a result of too-little support for the markets. It’s true that after a brief rebound in late 2009 and early 2010, pundits are calling for austerity measures out of the U.S. government, but if the economy slips again, more stimulus will be applied to “shock” the economy out of its stupor.

Can investors handle another decade of this? It isn’t a strong value proposition for investors who aren’t engaged in altering their asset allocation in coming years. In the first place, if your investing horizon is less than 70 years, “you can’t count on the long-term average of the market because you’re not going to be in it long enough to see how it turns out,” said Ken Kam of Marketocracy, which tracks investors’ portfolios on its Web site.

As 2009 came to a close, investors were feeling optimistic. A buoyant set of economic reports suggested the environment was on the mend, but a number of factors suggest growth will be lower in coming years than it had been in the late 1990s and mid-2000s. Many don’t want to be confronted with the reality that investment returns just aren’t going to be what people got used to—not if they’re sticking exclusively to U.S. big-cap stocks, anyway—and assume that everything that dies will someday come back. That’s a bad assumption.

Debt is the foremost factor that will block investors from earning the same kind of returns as they did through the 1990s. The U.S. owes a lot of people a lot of money, and much of the income generated by investors, companies, and government institutions will be spent servicing that debt rather than paying for new research and development or improved infrastructure. Of course, the U.S. is not an impoverished nation, like so many in Africa that are struggling to provide services to their citizens because of massive debts incurred by dictators in the past. Nor is it Argentina, which underwent a series of crises as a result of its heavy debt burden.

But the U.S., as of the end of 2009, had a debt level that fell short of just a few other countries in the world. In terms of debt levels as a percentage of our gross domestic product, we’re doing all right—ranked about 66th in the world in 2009, with debt amounting to about 39.7 percent of our total GDP, according to the CIA’s yearly World Factbook. (By far the worst-off is Zimbabwe, which has debt obligations of about 300 percent of GDP.)

That doesn’t tell the whole story, though. Our current account balance, which is a measure of our trade in goods, services, interest payments and profits, and a few other things, is at a negative $706 billion. That ranks worst in the world, and the second-worst, Spain, is nowhere near us, with a current account deficit of $154 billion.

When state and local governments are included, public debt continues to rise. Adding in household and corporate debt pushes the U.S.’s debt-to-GDP ratio to about 840 percent of GDP, which is plainly unsustainable. The Federal Reserve took on a big load of these obligations, in effect transferring them from corporate balance sheets to the federal government’s balance sheet. “Growth in the U.S. is going to be hampered by our debt burden for years to come,” said Rob Arnott, founder of Research Associates. “We are so addicted to debt that our debt burden is quite literally beyond anything any nation in world history has ever achieved.”

A McKinsey study pegs the U.S. debt as a percentage of GDP at 300 percent—which still trails the U.K. at 466 percent and Japan at 471 percent. And John Mauldin, chief investment officer at Millennium Wave Investments in Fort Worth, Texas, said in a recent commentary that deleveraging has a long way to go in the United States—perhaps another five or six years before the leverage accumulated over a period of decades is reduced to a more manageable level.

Other countries are more hampered by their debt levels, and concern about the financial health of those nations helped U.S. markets in late 2009 and early 2010 as the U.S. came to be regarded as the “best kid in the bad neighborhood.” U.S. Treasury debt remained at low yields, and that market continued to see substantial appetite for frequent sales of government securities as foreigners bought our long-term debt in lieu of purchases in troubled areas such as the euro zone, where the rising fiscal imbalances in the likes of Greece, Spain, and Portugal threatened to undermine the euro and other markets in that region.

But being the best-looking pile of garbage in the garbage dump isn’t anything to be proud of. The U.S. faces mostly unsatisfactory choices: raising taxes, reducing government spending, or, worst of all, default. The latter isn’t any kind of choice at all. Russia and Argentina both defaulted on debt, in 1998 and 2001, respectively, and a country that defaults quickly finds itself without a lot of friends in the investing world. Interest rates would likely soar, borrowing costs would become cost-prohibitive, and the dollar would get hit even worse than it has already been beaten up in recent years; it would be a disaster for the public debt and corporations alike.

What is more likely is that the U.S. continues in the current vein—a period of deleveraging, where companies try to pay down debt, while the government sector takes on more leverage to ward off depression-type conditions. At this point, in 2010, the economy appears to have escaped a depression, but the recession has been a devastating one, with double-digit unemployment, and the weight of government deficits and the poor decisions made by the private sector for several years are likely to result in an economy that grows more slowly for several years, if not more. Part of this is the consequence of profligate actions by the government during the first decade of this century, and unfortunately, while some may believe deficits can be ignored, they cannot—all bills have to be paid eventually. This, Pacific Asset Management’s Bill Gross argues, will hurt returns in coming years in the U.S., along with several other large industrialized nations.

The current political climate has only a small appetite for a robust Keynesian response. This refers to economist John Maynard Keynes, the Depression-era advocate of pump-priming government spending to shock an economy out of a severe depression. So in early 2010 Barack Obama, the U.S. president, started to talk of deficit reduction through targeted spending freezes. This was not meant to apply to certain entitlements, but the public’s strange desire to see the government’s balance sheet repaired to the extent that individuals and corporations have not repaired themselves is a bit misplaced, particularly decisions made in the middle of 2010 to cut off extensions of unemployment benefits, which will only hurt the economy more. It is, however, the reality of the United States, and such an effort also means that social programs will be taking a back seat to other efforts.

What this may do, unfortunately, is open up the possibility that the U.S. economy will backslide in terms of growth, after a surge that took the U.S. out of recession in late 2009/early 2010, at least temporarily. Double-dip recessions are rare indeed—the last one experienced in the U.S. took place amid an energy crisis and a massive rise in interest rates between 1980 and 1982. The U.S. entered recession in January 1980, was out by July 1980, and slipped back in just 12 months later, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, responsible for determining the cycle of business expansions and contractions. The last instance where two recessions followed so closely was in the aftermath of World War I. Many economists believe the extensive stimulus undertaken, along with policy efforts by the Federal Reserve, will keep the economy out of the abyss. But final demand remains weak, industrial activity is slack, and hiring is anemic, all recipes for a sluggish economic environment, and one that does not justify the 70 percent rally in stocks between March 2009 and March 2010.

So it’s back to the see-saw approach, one that wreaks havoc on those who elect to sit back and invest passively in index funds and not check their situation at the end of each month or at worst, at the end of the quarter. As the spring of 2010 wore on, economic data suggested a reasonable improvement in demand, but many investors, including Doug Kass, president of Seabreeze Partners Management in Palm Beach, Florida, said the rebound reflected an ongoing snapback from the period of late 2008 and early 2009 when consumers were more or less catatonic. As government stimulus programs wane, the possibility of subpar growth looms. Subpar does not refer to endless recessions—but 1 percent to 2 percent annual growth in gross domestic product, which is slow enough that stocks and other investment assets are likely to bounce to and fro, even after the massive 70 percent rally that the market has just experienced.

“I think you’re going to see the boom-and-bust cycle continue,” says Michael Lewitt, who heads the hedge fund Harch Capital Management in Boca Raton, Florida. “I see real issues in terms of trying to figure out what to do about the deficit, and I think it’s going to be a very, very difficult environment to make significant money in. You’re going to have to be willing to go short to really outperform. I don’t see the market itself growing tremendously—I see a lot of money that’s going to have to be diverted to servicing debt at the federal and state level.”2

Professors Ken Rogoff of Harvard and Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland have catalogued the average declines in the aftermath of full-scale banking crises like those that occurred in the U.S. They note that real housing price declines average about 35 percent over a six-year period, and equity prices fall by about 55 percent.3 Employment and output continue to suffer, and government debt rises to unheard of levels, largely because of the collapse in tax revenues as a result of the crisis. That’s where the economy is now. It’s a dire outlook for sure, and Rogoff/Reinhart have found that unemployment levels tend to remain elevated for five years after they rise sharply, putting the U.S. on track for a substantial rebound in job growth somewhere around 2015. Notably, unemployment in the late spring of 2010 was still close to 10 percent, and a broader measure of unemployment that factors in those who have ceased to look for a job was in the high teens. Such a job market does not argue well for continued investment gains, even if the wealthiest of consumers continued to spend. While some economic indicators suggest an improvement, the National Federation of Independent Businesses, which tracks the activity of small businesses nationwide, issued a dire outlook in April 2010, noting that small firm capital spending was at a 35-year-low and plans for future expenditures also remained low.4

An optimistic sort would respond to this sluggish commentary by suggesting that since equities and real estate have already suffered their requisite downturn, the markets should be on the verge of recovery. That is indeed possible—and part of the reason why many strategists have moved back into equities, particularly as the rally of 2009 got underway. But with a 70 percent rebound in stocks having already taken place, the best opportunity may already be past, especially as the economy continues to unwind from years of excessive leverage, and as valuation already suggests investors are pricing a lot of growth into an economy that may not deliver on lofty expectations.

Plenty of investors continue to prefer equities. But the reality is that see-sawing markets are likely to be the dominant condition for the next decade, especially if structural problems, such as the lack of effective regulation of financial institutions, are not addressed. The idea of another decade of flat returns is unacceptable, which is why smart investors believe the buy-and-hold approach has been consigned to the dustbin of history.

What appears to be the reality here is that the uncertain growth path of the U.S. and other developed nations in coming years due to rising debt levels will make allocating effectively, particularly to emerging markets, more important. It means they will also have to invest in corporate debt of well-run companies, as that can provide strong returns as companies have to continue to service their debts.

The Inflation Question

Investors are currently worried about inflation. There is some justification for this. The U.S. Federal Reserve, in concert with other world monetary authorities, is in the midst of a concerted effort to restore economic health and remove barriers to lending and capital formation in the largest global economies. With interest rates at rock-bottom levels in most major world markets, those institutions that have ready access to capital—for now that means large conglomerates—should have the means to borrow more easily to finance spending and investment.

If prices rise in the U.S. at a faster rate than our creditors, it will make our debt burden less onerous and easy to pay off, as the debts, valued in current dollars, will be easier to manage if the value of our dollars rises.

Unfortunately—and here’s where this matters for the individual investor—inflationary environments are unpredictable at best and often produce middling returns.

Investors are concerned that the rapid expansion of the money supply will fuel another asset bubble, this one sponsored by the leverage undertaken by the government, rather than the private or household sectors as was the case in the previous bubbles. If asset price inflation is followed by a jump up in price inflation in the real economy, it will make the investment environment more difficult. There are a few investments that are designed to shield investment portfolios from inflation, but stocks have not always been the best choice.

“People no longer think of stocks as an inflation hedge, and based on experience, that’s a reasonable conclusion for them to have reached,” said Richard Cohn, an associate professor of finance at the University of Illinois, in Business Week’s noted “The Death of Equities” cover story. But the experience at the time was important in understanding how equities performed in light of rising inflation. BW quoted Salomon Brothers, which pointed out that stocks boasted a 3.1 percent compound annual rate of return between 1968 and 1979, while the consumer price index rose by 6.5 percent annually. They noted that gold, diamonds (which almost nobody considers a viable investment vehicle), and single-family housing all outpaced the stock market during that period—and the price of oil didn’t do too badly, either.

One asset that certainly also runs into trouble during a period of heavy inflation is long-term bonds, particularly government bonds. With corporate debt, there’s always the chance of price appreciation based on fundamental factors related to a company, but government debt is unlikely to respond in the same way. Why is this so problematic for the average person? Because you’re likely to have made bonds and stocks the mainstay of your portfolio, and both assets are not in favorable positions as the next decade wears on.

Inflation has remained low for a number of years, but that trend may be ending, and certainly one of the markets that was broadly supported by falling inflation, bonds, could also have hit a peak. “You cannot make the argument now that we’re on a wave of declining interest rates,” says Kevin Flynn, a money manager with Avalon Asset Management. “You can argue as to whether we’re going into deflation or inflation, but we’re not going into a 20-year wave of falling inflation.”

Certain assets have done better than others when inflation got out of control. Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPs) are one natural way of hedging against rising inflation, but small-cap stocks, commodities, and real estate investment trusts have also been effective against inflation because they represent asset classes where prices are being constantly adjusted in recognition of a changing price environment. Small-cap stocks reflect companies that can see quick increases in their earning power as a result of rising prices, while commodities and real estate prices change in line with overall price changes in the economy (and sometimes faster). Long-term bonds, by contrast, have a set value for 10 or 30 years, and will not do well against inflation. Between January 1977 and April 1980, the inflation rate rose from about 5 percent to 14 percent on an annualized basis, and very few assets can keep up with that. A few do, however—and investors have to be ready for such a move, although probably not that drastic, in the coming years as the economy finally stabilizes.

Either way, the market could experience several more years of middling or up-and-down action. This means the buy-and-hold investor could end up holding stocks through a long slog before finally getting out, once again, selling at the wrong time. If investors end up at the same level they were ten years earlier, this puts even more pressure on that individual to outperform the averages as retirement approaches. Now a decade closer to retirement, their nest egg now relies more on the performance of investments and less on asset accumulation.

Debt Goes Around the World

The markets, as a result of the ongoing debt crises around the world, are likely to remain volatile and subject to gyrations as a result of tremors occurring in smaller countries due to the interconnectedness of financial institutions around the world. In late 2009 Dubai World, the state-controlled company based in the United Arab Emirates, said it was looking to delay its debt payments, raising fears of default by Dubai and sparking a sell-off in risk assets around the world. The emirate is still in the midst of sorting out the off- and on-balance sheet exposures to certain debts that they are struggling with as they now have to deleverage, that is, write down or pay off these debts as economic growth cannot sustain them. “Let Dubai be a reminder to all: Last year’s financial crisis was a consequential phenomenon whose lagged impact is yet to play out fully in the economic, financial, institutional and political arenas,” wrote Mohamed El-Erian of Pacific Investment Management in November of 2009.5

Stocks and bonds eventually recovered, but in early 2010, just a few months later, the markets grappled with scares of defaults out of Greece, one of the sicker countries in Europe in terms of financial health. With Greece having substantial holdings in Eastern European nations, the news hit those markets as well. Not long after that, China said it would try to restrict lending from its banks, once again damaging stocks. And then a crisis hit Portugal, as the Iberian nation found itself unable to sell as many of its own government securities as it wanted to, causing markets to gyrate once again. Spain followed. We’re not close to being finished.

The commonality here is that many of these nations, during boom times, borrowed money from creditors outside the country and used it to finance various large projects, both private or public. Investors were happy as long as debt was being serviced, but shocks rippling through markets in 2008 and 2009 caused certain countries’ currencies to decline in value, making debt service more difficult. As the problems individual banks had became more well-known, this resulted in a flight of capital, which only exacerbated the decline in the currency. Suddenly, loans that were easily serviced were now breaking the back of the balance sheets of banks anywhere from Iceland to Dubai. The need for nations to undergo severe restructuring programs—which will involve fewer public services and reduced economic assistance—means demand will be sluggish in a number of countries until the process of deleveraging is finished. Because of the extent of the borrowing through most of the 2000s, this is not going to be an easy time and makes it more likely that sudden eruptions in confidence will knock markets for a loop for a period of weeks or months.

This does not mean that every nation should automatically be considered suspect in terms of its debt and/or credit rating. But it does mean that investors are likely to be fickle, shifting allocations from one country to the next with wild abandon when trouble erupts. For now, Europe is the troubled area of the world, particularly the Mediterranean nations of Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Italy, along with Ireland. Eastern Europe is no picnic either. For those looking to invest internationally, diversification and more importantly, owning the entire market becomes paramount. While most indexes were hit hard in the aftershocks of 2008 and 2009, broader market indexes, such as the exchange-traded funds that followed emerging markets in general or the Europe/Asia/Far East areas were better situated than country-specific funds.

With the focus on international indexes much more intense than before, investors will have to reckon with the possibility that the U.S. will not be the world’s primary growth engine anymore. This economy is still huge, but the horrid meltdown of 2008 remains fresh enough in the minds of buyers. “It used to be that if you knew domestic equities and you knew them well you were fine, and you could succeed in the game, but now it’s gone international,” said Chris Johnson, head of Johnson Research Group in Cincinnati, Ohio. “Look at what happened with Dubai—that’s a relatively small amount of cash when you look at it. It’s a drop in the bucket compared to the amount we’re talking about here over the last two years, but it was able to send a pretty good ripple through the market.”

With many countries facing unsustainable budget deficits, and with growth uncertain in many of the nations that have driven world economic demand in recent years, you’re going to be dealing with choppy, uncertain markets for some time. It would be nice to be able to sit back, sock away the money in index funds, and forget about it, but the climate demands you pay attention. That doesn’t mean making this into agony—it needn’t be wrenching to try to figure out how to handle your portfolio—but above all, it will require flexibility and shedding yourself of the dogmatic approach and the clichés that pass for actual investment advice. This may mean a more active involvement in shifting assets, but those paths have their own peril, as it involves making bets at optimum moments, and many investors have a hard time doing this. It may be that it relies on tactical shifts in and out of risk assets all at once—again, a difficult chore, but one that can possibly be done with the right amount of homework. At the very least, rebalancing will limit overexposure to any one investment that has outperformed, and leave you less vulnerable to big declines in those assets.

Going Forward

This book is not meant to be a comprehensive approach to investing. It’s a big world, there are a lot of investments, and plenty of smart people out there who have kept a clear head in their years as investors and managed to do well over a long period of time without things getting complicated. Really, financial security is feeling secure in your decisions today and the long-term path you’re taking for years down the road.

This advice I’ve put forth admittedly falls into what my elders would have just called common sense. But they didn’t manage to find a way to live off modest salaries for a long retirement through luck—it involved counting pennies (and rolling those pennies into rolls and depositing them into the bank) and keeping an eye out on what lay ahead. The Depression-era generation got by with their savings, guaranteed pension benefits, and social security payments—and their retirement was often just a handful of years after a lifetime of work. It is more difficult for the boomer generation. Pensions aren’t what they were, subsequent generations face the possibility of reduced social security benefits, and they must take more direct involvement in their own retirement. Many of you have been scared out of your wits by this meltdown. There is time to recover—it just can’t be done the same way. And it certainly can’t be done by simply forgetting about it and assuming everything will work out.

This approach is not the only one, of course. But the common sense that I’m imparting shouldn’t be overlooked. Most of all, keeping a clear head when it comes to your money is of prime importance. You are allowed to sell things if it will preserve assets that you don’t want to lose. You can avoid buying faddish stocks or letting your investments run wild, and you still can have success that will prepare you for retirement. And once you make those decisions, don’t look back on them.

I hope this book has been edifying, thought-provoking, and a bit entertaining as well. If sure answers existed in investing, people would follow the same rules, time and again, but they don’t. People will continue to try to find alternate ways to build models to come out ahead of everyone else, or so they think. The investing world is going to be an increasingly complex, volatile one. It doesn’t have to be a crazy experience for you, though. Simple rules can help preserve your money—and your sanity.

Boiling It Down

• Be prepared for anything in the next ten years. The stock market could go nowhere; it isn’t destined to rise just because it has been suffering for most of a decade.

• Look to allocate assets in areas where debt is not the overriding factor, such as in many emerging markets. For another twist on that, well-managed companies with limited amounts of debt are potential bond market investments (through an index of high-rated corporate bonds).

• Common sense rules. Save your pennies and invest them in the markets carefully, keeping your costs low and your trading minimal.

• Avoid fads like the plague. If everyone is doing it, eventually it’s not going to feel good for anyone.

• Index funds and exchange-traded funds that mimic indexes are great building blocks for a well-managed, low-cost portfolio.

• Don’t forget about rebalancing.

• Expect see-sawing markets to continue. Make sure you don’t have more than about a quarter of your assets in large-cap domestic stocks; investing in commodities, various types of bonds, and emerging markets should help offset the volatile stock market.

• Avoid following advice based on clichés or aphorisms.

• Don’t be afraid to sell a losing asset.

• Admit it—you don’t know everything. And that’s okay.

Endnotes

1 “Fundamentals: Lessons from the ‘Naughties,’ Research Affiliates, February 2010.

2 Author interview.

3 Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “The Aftermath of Financial Crises,” December 19, 2008, paper prepared for American Economic Association meetings in San Francisco, California, January 3, 2009.

4 NFIB Small Business Economic Trends, April 2010, http://www.nfib.com/Portals/0/PDF/sbet/SBET201004.pdf.

5 Mohamed El-Erian, “Dubai: What the Immediate Future Holds,” The Daily Telegraph, November 29, 2009, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/6678194/Dubai-what-the-immediate-future-holds.html.