9.1 France Scully Osterman, Light Pours In, from the Sleep series, waxed salt print on Strathmore paper, 8 × 10 in. (20.32 × 25.4 cm), 2002. ©France Scully Osterman.

The Sleep images offer contradictions: a sense of voyeurism juxtaposed with a moment of innocence; a reminiscence of death (or post-mortem), yet full of movement and energy.

The earliest salted paper prints were made in the 1840s and 1850s from calotype paper negatives, waxed paper, and albumen-on-glass negatives. Salt prints were also sometimes called “Crystalotypes.” The term was used by John A. Whipple of Boston specifically for salt prints exclusively produced from glass negatives including albumen-on-glass, and wet-plate collodion negatives.

The wet collodion negative process was published by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and quickly adopted by photographers all over the world because, unlike the daguerreotype process, it was less expensive to produce. Salted paper and albumen prints were used by wet collodion photographers throughout the collodion era (1851–1880). After the albumen print became popular, salt prints were often referred to as “plain” prints. This may have been because the albumen print had a glossy appearance, a much desired aesthetic of the period.

Salted paper prints were also used as a base for over-painted solar enlargements from around 1859–1870. These required an exposure of at least an hour for the solar projected image to be printed deep enough as a reference for the application of chalk, charcoal, or pastel.

Always wear disposable gloves when working with the silver nitrate solution, as it will stain hands and permanently stain clothing.

Silver nitrate is a corrosive and should be handled with care by wearing protective gloves. Avoid contact with eyes.

Dispose of solutions responsibly. If your town has a hazardous waste area, use it.

Do not use any photo equipment, such as Pyrex ™ baking dishes, for any other purpose.

9.2 Method Overview

1. A piece of paper, slightly larger than the negative, is carefully floated on, submerged in, or brushed with a solution of ammonium or sodium chloride and water.

2. The salt solution may also include a small amount of sizing such as gelatin or one of many starches, such as arrowroot or tapioca. The sizing step is optional, but is sometimes added to prevent the silver chloride from going deep into the paper fibers. This not only enhances the detail of the image but also alters the final image color.

3. After coating with the salt solution, the paper is either dried with a hair dryer or hung up to dry. Once perfectly dry, the paper is then coated with silver nitrate solution (by either brushing or floating) and dried again. The paper is now covered with the compound of silver chloride and an excess of silver nitrate and is sensitive to light.

4. The sensitive paper is placed in contact with a negative in a contact printing frame and exposed to sunlight or an ultraviolet light source. Exposure to light converts the silver chloride to metallic silver. The longer the exposure to light, the darker the metallic silver deposit will become. Areas not exposed to light remain the color of the paper. This action of photolysis is continued until the image is intentionally printed darker than what looks right for the final image.

5. The fully formed print is then washed in slightly chlorinated water to remove excess silver nitrate. It is then toned with gold chloride (toning is optional) and fixed in sodium thiosulfate (aka hypo) to remove the deposits of unexposed silver chloride, and hypo cleared. The print is subsequently washed and dried.

6. Once completely dry, a protective finish maybe be added to protect the metallic silver in the print from harmful atmospheric sulfides. This chapter discusses how to coat the print with bees wax. Coating the print with wax also increases contrast, making the DMax darker, while lending a satin finish.

1. Paper. One hundred percent cotton or acid free paper, strong enough to withstand extended washing, such as Fabriano Bristol.

2. Chemicals and equipment.

a. Salt Solution:

Pyrex beaker (large enough for the amount of salting solution you plan to mix)

Stirring rod or spoon

Hot plate or stove top (if using gelatin sizing)

1.5 grams ammonium chloride or sodium chloride (no iodine added; Kosher salt is perfect)

1.5 to 2 grams food-grade gelatin, like Knox (gelatin for sizing is optional)

100 ml (3.38 oz.) distilled water

b. Silver Solution:

15 grams crystal silver nitrate

100 ml (3.38 oz.) distilled water

Glacial acetic acid (if needed)

Pyrex beaker (large enough for the amount of salting solution you plan to mix)

pH strips

Disposable gloves

Rubylith (see Creating the Photo-Printmaking Studio, page 102) or a piece of red glass large enough to cover light unit (optional; needed if floating paper on silver solution)

Light unit (optional; needed if floating paper on salt or silver solution)

c. Toner: Gold Chloride Stock Solution:

1 gram pure gold chloride

Distilled water

Brown glass bottle that will hold 200 ml (6.76 oz.)

Gold Chloride Working Solution:

700 ml (23.7 oz.) distilled water

10 ml (1 grain) gold stock solution

Pyrex glass beaker large enough to hold a minimum 700 ml (23.7 oz.)

Very small graduated cylinder (20 ml or less than 1 oz. capacity)

Glass stirring rod

pH test strips

Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda)

d. Fixer:

1000 ml (33.8 oz.) warm water

150 grams (5.25 oz.) sodium thiosulfate (“hypo”)

2 grams (slightly less than ½ teaspoon) sodium bicarbonate

e. Hypo Clearing Solution:

30 grams (1 oz.) sodium sulfite

3000 ml (101.4 oz. or 3.17 qt.) water

f. Waxing (optional):

Beeswax, lavender oil

Removable masking tape

Microwave or hot plate

3. Ultraviolet light source or direct sunlight, contact printing frame with a hinged back.

4. Other items. Shallow glass bowl or saucer; cotton wadding; flannel cloth (used for baby clothes and winter sheets); smooth, flat worktop (smooth counter, sheet of plexi-glass or glass), timer or watch. (Osterman advises that accurate gram scales can by purchased in kitchen and sporting shops. L.B.)

5. Materials for contrast control (optional): Tissue or tracing paper; household ammonia; large plastic storage box with lid; rolled cotton wadding (can be found in some pharmacies).

6. Materials for coating the paper. If you choose to brush on the emulsion, you will need rolled cotton wadding; small bowl; a smooth board for coating 2 in. (5 cm) larger on all sides than your paper; blotting paper; clear packing tape; removable “painter’s” masking tape; hair dryer or a clothesline and spring-type clothes pins.

If you prefer to float the paper on the solution, you will need a Pyrex™ baking dish, clear glass tray, or dedicated plastic tray; clothesline and spring-type clothes pins; steamer, humidifier, or tea pot (only needed as an option for working in a dry climate); toothpick or small brush.

7. Table light unit large enough to hold Pyrex™ baking dish (optional).

The sizing and salt solutions are not light sensitive and applied under any type of light.

If using gelatin sizing: add gelatin to cold water and let sit for 15 minutes until gelatin softens. Then heat the water and softened gelatin on a hot plate and stir until dissolved.

Add the ammonium chloride to the warmed solution and stir until dissolved. Let the solution cool to room temperature before using. (If not adding gelatin, salt will dissolve easily in room temperature water.) It may be used slightly warm or cool, but should not be used hot. However, if the solution with gelatin gets cold, it will gel and will have to be re-warmed. Temperatures in the 70–78°F (21–25.5°C) range work best.

METHOD I: BRUSHING

It is more difficult to make even coatings by brushing than by floating, but brushing does not require as much solution as using a tray and floating the paper. Once mastered, it is a very economical way to prepare the paper (especially when sensitizing). It’s the perfect technique when you only want to make a print or two, and easier to do if you don’t use the gelatin sizing in the salt solution.

To prepare the coating board, cut the blotter to slightly smaller than the board. Tape the entire perimeter of the blotting paper onto the board. Tape the four corners of the paper to the center of blotting paper. After the blotting paper has been used extensively and is contaminated with silver, it can be replaced with a fresh piece. Another option is to cover the board with clear packing tape, which can then be wiped clean between coatings.

Pour some of the salting solution into the small bowl. Ball up cotton by pulling the loose strands to the back and, wearing gloves, dip the cotton into the salt solution so that it is thoroughly wet, but not dripping. Apply to the paper in slightly overlapping lines, in one direction only. Allow an extra margin beyond what you will need for your print. After coating the whole sheet, quickly turn the paper 90 degrees, and go over the paper again with the same piece of cotton. Do not apply more solution, unless the cotton “shreds” which means you did not apply enough. Turn the paper 90 degrees once more and brush the paper with the same cotton ball a third time.

These repeated steps are meant to help distribute the solution evenly, without puddles or streaking. A cheap turntable, also called a Lazy Susan (available at a kitchen store), under the coating board makes this process faster and easier. The solution on the paper should be a satin, even wet finish. Allow the solution to spread for a minute before drying. Dry thoroughly with a hair dryer.

METHOD II: FLOATING

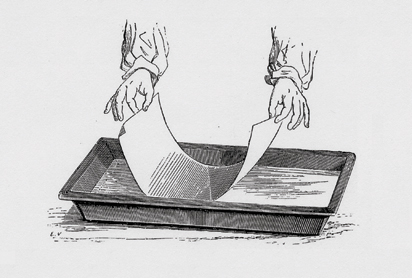

9.3 Floating Paper on Salt Solution

This method is recommended if you are using gelatin sizing and if you are coating many sheets of paper. Once dry, coated paper can be stored indefinitely as long as it is stored in a clean, dry environment.

The salt solution must be in a tray slightly bigger than the paper. The author uses Pyrex trays for prints 8 × 10 and smaller, but any glass, ceramic, or dedicated plastic tray may be used. Enamel trays are appropriate, too, unless they are chipped. Avoid bubbles when pouring salt solution into tray. Mark one side of the paper on a corner with a pencil before floating so that you will know later which side is salted.

To completely avoid bubbles, the author suggests using a clear Pyrex™ tray for the solution, which is placed on top of a light table. This makes it possible to see through the paper, and check for bubbles once the paper makes contact with the solution. (For the silver solution, first cover the light unit with rubylith or a piece of red glass which covers the light unit completely.)

Fold the two opposite ends of the paper about 1 cm (less than ½ in.) to use as handles. Hold the paper by these two ends and allow the center of the paper to curve gently downwards. (See Figure 9.3, Floating Paper on Salt Solution.) If the room is very dry, first humidify paper with a sick room humidifier or teapot before floating. Floating is also easier with thinner papers, such as Crob’art or Universal Sketch.

Set the lowest part of curved paper onto bath so that only the very end of the curve nearest you makes contact with the solution. Then, gently lower the rest of the center section onto the solution. Now, lower one side of the paper onto the solution and then the other side until all the paper is floating upon the surface except for the handles on the ends.

Once the paper is floating, it may begin to curl upward on the ends. If so, gently hold down the ends with the tips of your gloved fingers until the front of the paper absorbs enough solution to make it lay flat. Make sure that you don’t push the paper too hard or the back of the paper will go under the solution. Once the paper lays flat on the solution you should lift up one side of the paper and inspect for bubbles. If discovered, they should be popped with a toothpick, small brush, or the tip of a piece of paper. Check the other side as well. (If you are using a light table under the glass tray, then you can see any bubbles through the paper.)

Float the paper on the salting solution for a total of two minutes, counting from the time the paper lays flat. After two minutes, slowly pull the paper up from the solution by one corner, and hang the paper by two corners with spring type clothespins on a line to dry. Blot any droplets on the bottom edge of the paper with a disposable paper towel. The salting solution is not light sensitive so this operation can be done in daylight. Once the paper is dry it can be kept indefinitely. Flattening the paper in a book or with dry mounting press makes subsequent floating on the silver solution much easier.

When needed, the “salted paper” is taken to a darkroom illuminated by red or yellow light. After the paper is brushed with, or floated on the surface of, silver nitrate solution, it is then removed and hung in the dark to dry. It should be used as soon as possible after it is dry, preferably within an hour or two.

If gelatin or other organics were included in the formula, throw away the salting solution when done. If gelatin is not added, you can filter it and reuse it. (The author uses a funnel with cotton balls to filter).

While the silver solution is not affected by light when first mixed, once it has been in contact with organic matter, like paper, salt, and/or gelatin, it’s important not to expose it to strong light. Coating the paper can be done in a room with a dim white light, but the coated paper should be dried in a darkroom or room illuminated only by red, amber, or orange light. You will be handling the sensitive paper and exposed print in subdued white light during processing, but it’s best to limit exposure whenever you can to prevent fogging.

First, you need to make the silver solution. Dissolve silver nitrate in distilled water. Measure the acidity with pH strips. (If printing in hot weather, add small amounts of glacial acetic acid until you make the pH = 2.5 to 3.5. Pour the solution into a small bowl for dipping cotton and brushing. (Floating requires a greater volume of solution, and depends on the size paper and tray you are using.)

Instructions for brush coating and floating paper on the silver solution are the same as for applying salt, except that the procedure is done in subdued or safe light conditions. It’s possible to use a 60 watt tungsten bulb six feet (1.8 m) away from the coating area for sensitizing, though a bright yellow or red light is safer.

Once coated with silver solution, the paper may be hung on a line with clothespins in a darkened room or dried quickly with a hair dryer. It is very important to make sure the paper is as dry as possible before using it for printing. Failure to pay attention to this step can result in blotchy prints and also damage to the negative.

Once dry, the sensitized paper and negative are placed in contact with the sensitive side facing the image or emulsion side of the negative. This is done by first placing the negative into a contact printing frame image or emulsion side up. Then the paper is placed on top of the negative, coated side down. The back of the printing frame is closed and the frame placed in the sun or under a UV light unit.

9.4 Opening the Printing Frame to Check Print Exposure

Photographic printing frames are fitted with a hinged back to allow inspection of the print, without changing the registration of the paper to the negative. After the frame has been exposed to light for a few minutes, take it to an area where the light is subdued and open one half of the printing frame to inspect the progress of printing out. See Figure 9.4, Opening the Printing Frame to Check Print Exposure.

The print should be exposed to look two shades darker than what would be considered normal for the finished image. If the image is too light or even looks perfect, close the back and continue to expose the print until the areas of maximum density are a shade or two darker than the desired finished print. The print will lighten considerably when fixed.

Pyrex™ glass baking dishes are perfect trays for all of these operations. They should be well cleaned with rottenstone or kitchen cleanser and tap water, given a final rinse with distilled water, and allowed to dry upside down before using for photography.

The print is given an initial “precipitation” wash (see below for more details) in tap water to remove the excess silver nitrate. Once the excess silver is completely removed, the print can be toned with gold or go directly into the fixing bath. The print is fixed in sodium thiosulfate, aka “hypo.” An optional sodium sulfite bath helps to make the print easier to wash. The print is washed in running water or several changes of clean tap water and dried between blotters or with a hair dryer.

The “Precipitation” Bath (First wash)

The print is first placed in a tray of clean tap water. Municipal tap water in the United States often contains chlorine salts (sodium chloride). The excess silver will react with the chlorine in the tap water, precipitating the extra silver chloride on the paper. This will appear as a milky white haze in the water. When using tap water without chlorine, you must add a pinch of table salt to this bath. A dark tray makes observing the silver chloride much easier. The water from this first precipitation bath should be changed about three times. When there is no longer any milky white silver chloride, and the water remains clear, then wash the print with one more change of clean water. The print is now ready for toning (optional) and fixing.

6. TONING THE PRINT (OPTIONAL)

To Tone or Not to Tone

The print must be fixed to remove the unexposed silver chloride. Failure to thoroughly fix and wash the print will cause it to fade in time. Toning is done in order to apply gold to the silver image. In theory, this helps to preserve the print, though if the print is not fixed or washed well, no amount of gold will help; it will fade to a greenish yellow color. For the most part, toning is really done for aesthetic reasons; to modify the final image color. The more you tone a salt print with gold, the cooler the final image color. If you like warm or cool brown hues, pass over the following toning section and go right to the fixing instructions. If you wish to tone the print keep reading the next paragraphs on gold toning.

Gold Toning

Gold toning is usually done before fixing. There are many different chemicals that can be added to change the pH of the gold solution. The following formula works well to produce purple brown tones and can be used immediately after mixing. More gold can be added during the printing session if it seems to slow down, but the working solution should be discarded at the end of the day.

Gold Chloride (Stock Solution)

Gold chloride is always sold in small glass ampules containing 1 gram. Remove the top (or break the sealed ampule) and place the entire container into a 200 ml brown (6.7 oz.) glass bottle containing 154 ml (5.2 oz.) distilled water. Because 1 gram is equal to 15.4 grains, every time you need a single grain of gold for a toning formula measure 10 ml (.33 oz.) of this stock solution.

Basic Bicarbonate Gold Toner

(Working Solution)

Measure out 1 ml (.03 oz.) stock gold solution and add this to 700 ml (23.6 oz.) distilled water. Add a half teaspoon of sodium bicarbonate and stir the solution. Check the pH with test strips. Add more bicarb as needed until the pH is 8.0. Pour into a clean glass tray.

Place the washed print into the gold toning solution and rock the tray gently. Observe the tonal change. If the print tones very quickly, add more distilled water to the solution. It should take at least two minutes to change the print color from a red hue towards a purple brown. When you like the color, place the print into the fixing solution.

Fixing will always lighten the hue and reduce the density of a print. If a toned print is placed into the fixer and you observe a considerable loss, it means that the print was not toned enough. Deep toning can only be done to deeply printed prints, and deeply printed prints can only be made with strong negatives.

After the first “precipitation” wash, the print is placed in toner. If not toning, the print is placed directly into the fixer (formula above) for at least five minutes with agitation. The tray should be agitated continuously. During this fixing stage the tones of the print will shift from purple brown to a warmer milk chocolate or even yellow depending on the sizing of the paper, the amount of gelatin or starch mixed with the chloride, and how deeply the image was printed.

Using a hypo clearing agent, such as sodium sulfite, allows washing the fixer to be more effective. This means that the washing time can be reduced. You do not need to use a clearing bath, but it’s handy when you’re short on time or just want to do the best possible processing: Add 30 grams (1.05 oz.) sodium sulfite to 3000 ml (3.17 qt.) water and mix until dissolved. The print is placed into a bath of sodium sulfite for three minutes, agitating continuously. Sodium sulfite acts as a hypo clearing agent to aid in removing excess hypo and make the final water wash more effective.

The final wash for prints not cleared in sodium sulfite should be at least 30 minutes in running water, or wash the prints in a tray of water with constant agitation. Change the water at least four times over a 30-minute period. If the print was cleared in sodium sulfite, wash for 15–20 minutes in running water, or wash the prints in a tray of water with constant agitation, and change the water at least four times over a 20 minute period.

The washed print can then be removed from the water, placed on a blotter and covered with a second blotter. Apply gentle pressure to the top blotter to absorb water from the print. Then place the print on a clean blotter and allow to dry, or dry with a blow dryer.

10. PROTECTIVE COATINGS (OPTIONAL)

The metallic silver in printed out images is very fine and as such, susceptible to atmospheric conditions. Such prints are especially vulnerable to sulfides in the air which may cause deterioration, loss of density, and migration of silver particles. In the nineteenth century coatings were applied to salted paper prints to protect them from the sulfurous atmosphere. These coatings included albumen, varnishes, gelatin, and various starches.

The most effective way to protect a salt print is to coat the surface with wax, thereby protecting the silver from harmful atmospheric effects. Waxing adds also depth to the tonality of the print and imparts a beautiful satin finish.

Waxing

Beeswax is usually sold in the form of candles or cast shapes for craft purposes. To use this wax for coating prints you must first change it to a usable form. Place some beeswax in small saucepan and melt under medium high heat. Be careful, wax is very flammable! Spread a large sheet of tinfoil onto a counter top and bend the edges up to form a tray. When the wax is completely melted, pour the hot wax out onto a sheet of aluminum foil. When cool, the foil can be flexed to release the wax in thin chips. If it sticks to the foil, place the wax-covered foil in the freezer for a few minutes and try again. Put the chips in a zip lock plastic bag for storage.

Put a few wax chips in a shallow glass bowl and place this in a microwave or on a hot plate on high heat until the wax melts. Carefully remove from heat and allow the wax to cool and solidify completely. Make a rubbing tool by placing a 2½ in. ball of cotton wadding in the middle of a piece of 7 × 7 in. cotton flannel. Draw up the edges and form a door knob-shaped rubbing pad. This will be used to apply the wax to your print.

Tape the entire perimeter of the print onto a smooth counter top or piece of glass taped to a table top. Make it as flat as possible. Add about 15 drops lavender oil on the wax and use the rubber pad to work it into the wax. It will take some time with a new rubber. You are looking for a very even consistency of wax on the bottom of the rubber that is about the viscosity of thin lip balm. Continue to add lavender oil to maintain the viscosity of a thin paste.

Apply the wax to the surface of the print by rubbing in only one direction. Do not go back and forth! This could cause the rubber to grab the print and tear it in half. The wax should go on smoothly with little effort. If the wax seems stiff, add more lavender oil to soften it so that the wax goes on evenly. Remember that you want to wax the print, not oil the print. Be sure the oil is well mixed with the wax.

Once you have covered the entire print, wax from one of the sides to be sure the wax is embedded in the fibers of the print. After waxing from one side, use your fingertips to continue to work the wax deeply into the paper.

Allow the wax to rest on the print for a few minutes and then remove excess by gently rubbing with a clean piece of flannel cloth. Once the excess is removed, you may now lightly buff the finish with a clean piece of flannel to a satin sheen. Tape should be removed slowly. To avoid tearing, slowly and carefully pull tape away at a 90 degree angle while holding down the edge of print with clean fingertips.

9.5 Printing in Direct or Filtered Sunlight

CONTRAST AND NEGATIVE MANIPULATION (AS NEEDED)

The salt and silver ratio in this manual is formulated for the typical calotype or collodion negative of the nineteenth century. Salt printing was not generally done with gelatin dry plates or flexible films. If you try to use a film negative that works well for modern developing out papers, it will not have the potential to make a good print using the salt printing technique. Digital negatives can be tweaked to print as a warmer image color, producing “spectral density.” This additional spectral density can be made to print excellent salt prints.

You can manipulate the contrast of a salt print by controlling how fast the light converts silver chloride to metallic silver. This can be done by either printing with a weaker light (e.g., on a cloudy day) or the use of tissue overlays.

Tissue Overlays

The most important factor in the quality of the final print is the character of the negative. It is very difficult to make a great print from a weak or thin negative. Slowing down the printing process, however, will increase the contrast. The easiest way to do this is to tape one to three layers of tracing paper over the top window of the printing frame. Frosted white or ground glass can also be used. An alternative is to print on a cloudy bright day or in diffused light. See Figure 9.5, Printing in Direct or Filtered Sunlight.

Fuming

Raising the pH of sensitized paper with ammonia is an effective means to make the paper more sensitive and increase contrast. This is done by taping the corners of the paper, emulsion side out, on the underside of a lid from a large plastic storage box. Place a layer of cotton wadding in the bottom of the box and drizzle an ounce or two of household ammonia upon the cotton. Secure the lid and fume the paper from 1–4 minutes as a test. Remove the paper and allow it to out-gas for a minute before placing it in the printing frame. Fuming should not be done in the same room you are processing the prints.

9.6 Mark Osterman, The Rhoads Incident, from the Amnesia Curiosa series, gold-toned salt print on Arches Platine paper, from an 8 × 10 in. (20.32 × 25.4 cm) collodion glass negative, 2006. ©Mark Osterman.

Based on a tragic fire in the Rhoads Opera House (1908, Boyertown, Pennsylvania) that was started by the magic lantern projectionist.