Healthy Food Choice and Dietary Behavior in the Elderly

Christine Brombach1, Marianne Landmann2, Katrin Ziesemer3, Silke Bartsch4 and Gertrud Winkler5, 1ZHAW, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Wädenswil, Switzerland, 2Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Jena, Germany, 3University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany, 4Pädagogische Hochschule Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany, 5Albstadt-Sigmaringen University, Sigmaringen, Germany

Abstract

Eating is like breathing: inevitable and a requirement for survival. However, unlike breathing, which functions automatically and is geared by reflexes, eating behavior is far more complex. Eating is far more than simply providing the body with nutrients.

Addressing the issues of aging and dietary behavior requires consulting a multitude of disciplines and examining a wide range of research topics and studies. We assume that it will require both a natural science approach and a social science approach; the two approaches adhere to different paradigms, methods, and research designs and therefore different foci. We denote that aging, nutrition, physiological needs, and nutrients are part of a natural science paradigm and that getting old, eating, meals, and an eating biography refer to everyday life events and a social science paradigm. Dietary or eating behavior in the elderly thus nurtures both paradigms, yet in this chapter we will focus on the social science aspects.

Humans tend to eat what they are used to eat denoting and what they have learned to like. Food behavior is learned behavior and highly reflects routines and habits, reinstitutionalizing an ongoing process of dietary habits each day. This chapter will look at biographical and cultural factors contributing to and shaping our daily food choices and eating behaviors. We start by addressing what we know from literature and then present two studies we conducted to learn more about biographical and intergenerational factors contributing to food behaviors.

Keywords

Nutritional behavior; food intake; eating biography; food culture; contextual influences

Why Do We Eat What We Eat?

From epidemiological studies we know that well-being and health are related to nutrition (Köster, 2009; Furst et al., 1996; Bisogni et al., 2002; Peel et al., 2005; Conklin et al., 2014; Mozzafarian, 2016). For our biological survival, we need to furnish our body with food. Eating and drinking constitute part of our daily actions to maintain our life. The word eating carries a double meaning: the act of nourishing, which refers to our physiological status, and the social act of eating, which is transformed and constituted by norms, values, traditions, and transported sociocultural constructs of what, how, when, and with whom we eat (Furst et al., 1996; Shatenstein et al., 2013; Dickens and Ogden, 2014; Winter Flak et al., 1996; Wansink and Sobal, 2007; Wansink, 2010). Newborns learn that feeding occurs periodically, encompassing specific foods that are (usually) provided by their mothers. A baby´s caretaker resumes her own childhood experiences, thus carrying on the social dissemination of eating habits. Knowing and learning about food, eating, and eating behavior—such as the use of cutlery, the number and typical composition of meals per day, table manners, and taste—are acquired within the primary social group of the family (Methfessel et al., 2016; Edstrom and Devine, 2001; Atkins et al., 2015; Visser et al., 2016; Vabo and Hansen, 2014; Falk et al, 1996).

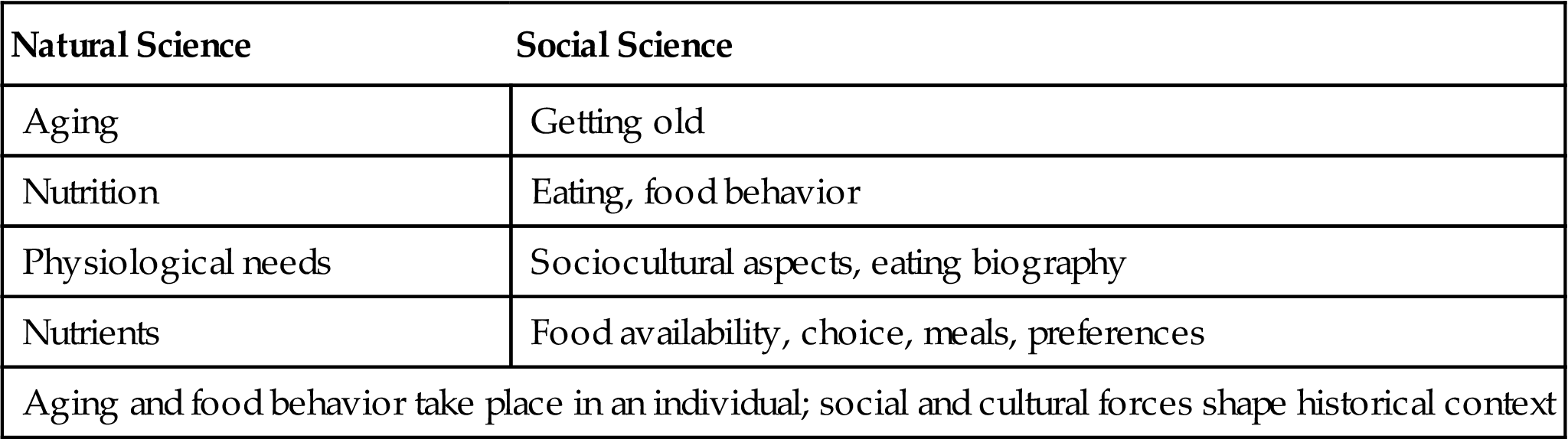

Studies on eating and eating behavior from the perspective of social sciences provide insights and help answer the question “Why do we eat what we eat?” (Barlösius, 2011; Köster, 2009; Devine et al., 1998; Devine et al., 1999; Wansink and Sobal, 2007; Just and Wansink, 2009). Even so, another paradigm other than a natural scientific approach is required (Table 11.1). Eating behaviors encompass complex actions that are socially shaped and further refined over a person’s lifetime (De Castro, 2009; Köhler et al., 2008; Kim, 2016). Eating behaviors refers to food-related actions, including growing, shopping, storing, preparing, and eating food, as well as cleaning up afterwards and planning for following eating occasions. It is assumed that eating and nutritional behaviors result from lifelong experiences, so it is important to understand the life course and biographical factors in relation to eating and drinking (Furst et al., 1996; Sobal et al., 1998). Insight into the onset of individual eating behavior requires carrying out studies in which eating behavior is mediated within the frame of everyday life situations (Wansink, 2010). In addition, studying eating behavior in the context of an intergenerational approach might help deepen our understanding of the values passed on through socialization (Jones, 2015). Literature reviews reveal that studies on intergenerational influences on dietary behavior have hardly been examined (Brombach et al., 2014a,b; Stafleu et al., 1994; Vauthier et al., 1996). A study conducted by Ikeda et al. (2006) examined the diets of black American women in the course of three generations. They concluded that the grandmothers influenced the mothers’ diets but not those of their granddaughters. In addition, the nutritional quality of the mothers’ and daughters’ diets was not similar (Ikeda et al., 2006).

Table 11.1

Two Paradigms, Two Sides of Food Behavior in Aging

| Natural Science | Social Science |

| Aging | Getting old |

| Nutrition | Eating, food behavior |

| Physiological needs | Sociocultural aspects, eating biography |

| Nutrients | Food availability, choice, meals, preferences |

| Aging and food behavior take place in an individual; social and cultural forces shape historical context | |

Determinants of Dietary Behavior

Eating and drinking are daily tasks that furnish our bodies with adequate amounts of nutrients and water and provide energy. On average, each person in a Western society consumes as much as 1.27 metric tons of food per year1. In the 1950s, German sociologist Georg Simmel described in an essay the common denominator that all humans share—meals and companionship (Simmel, 1957). Over their lifetimes, humans gather and share food for meals, but the most intimate shared meal is the start of a personal eating biography: when a mother nurses her baby, as anthropologists have assumed for decades (Douglas and Nicod 1974; Goody, 1982; Harnack et al., 1998; Murcott, 1995; Murcott, 1997). How and why do we learn to eat what we do? On which accounts do we make up food choices? We need to understand it first; otherwise we will not be able to support for healthy dietary behavior. In order to understand why people eat what they eat we can learn from elderly since they are experienced in their dietary behavior (Naughton et al., 2012; Ball et al., 2006; Edstrom and Devine, 2001; Wethington, 2005; Dean et al., 2009). On average an 80-year-old person consumed more than 50 metric tons of solid foods and 50 metric tons on liquid foods and consumed around 100,000 meals (own calculation). Despite the fact that eating and drinking are fundamental for our surviving; our daily food intake is by no means just a trivial biological action. Humans have no instincts such as animals do to guide their food intake. Humans have distinct eating behaviors which are culturally shaped and formed according to social rules, norms, and values of a given society (Fischler, 1988; Dean et al., 2009; De Vriendt et al., 2009; Conklin et al., 2014; Köster, 2009; Gatenby, 1997; Gibeny and Wolever, 1997; Blane et al., 2003, Kong et al., 2016). Each society defines which foods are edible or allowed to eat and which are not, which foods are valued and which foods are detested. Such food attribution or connotations differed throughout history of mankind (Goody, 1982; Lévi-Strauss, 1965; Mennell, 1985; Mennell et al., 1992; Barlösius, 2011), and even within individual life course foods considered to be adequate to eat, change. While we eat certain foods solely during infancy such as mushed food or infant food, we consume different foods in adulthood, e.g. wine. At specific times, often distinct foods are eaten and are part of certain festivities such as Christmas cookies or birthday cakes. Foods are valued differently in cultures and religions, while there are some foods forbidden in a culture, the same foods may be highly valued in another (Douglas and Nicod, 1974; Mennell et al., 1992; Goody, 1982). Prominent examples are insects which are not allowed for sales and prohibited on the food markets by most European food laws while insects are treasured foods in e.g. Asian countries or food valued in Europe such as blood sausages are taboo food in other cultures. Values and norms such as religious rules outlaw foods that are culturally accepted in other societies for examples alcoholic beverages or pork. Yet, despite different food habits and food-related norms, all humans share, that foods are eaten in situations we describe as “meals” denoting that there are norms, rituals, times, and routines that accompany food intake. Georg Simmel, a German sociologist described meals as the smallest denominator that all humans share (Simmel, 1957).

Food and eating behavior are inherently connected with many aspects of daily living and are formed and shaped over a lifetime. Eating behavior is guided by numerous practical and social concerns and by traditions, daily routines, and individual rituals (Fischler, 1988; Dean et al., 2009; De Vriendt et al., 2009; Conklin et al., 2014; Köster, 2009; Gatenby, 1997; Gibeny and Wolever, 1997; Blane et al., 2003). Studies of family meals (Brombach, 2001; Mäkela, 1995; Bartsch, 2011) found that the table was the forum for exchanging news and an instrument used by parents to instruct, educate, punish, or reward children in respect to the correct eating behaviors and table manners as well as generally acknowledged correct behaviors and socially shared norms and values (De Almeida Mota Ramalho et al., 2016). In his study on distinctions, Bourdieu (1984) found a certain habitus to be a distinctive criterion of class members. Habitus is learned and shaped within the social class an individual is brought up in.

We do not thoroughly understand the complexity of potentially independent and joint influences that shape and model eating behavior over the life course (Hummel and Hoffmann, 2016). Looking from a life course perspective and focusing on healthy elderly people, however, may reveal the trajectory of eating behaviors and their subsequent well-being later in life.

Food choices and life course influences have become a prominent framework in research on food behavior (e.g., Sobal et al., 1998; Sobal and Hanson, 2011; Sobal and Nelson, 2003).

Humans become socialized according to their family upbringings but are also subject to sociocultural factors that help make up any individual’s life course. To help our research, we developed an overview of contextual influences in Germany and Switzerland (Fig. 11.1), which we see as an example for the sociocultural, political, and technological influences that shape and model food trajectories and eating behavior throughout the life course. The factors are different in each culture, but we assume the process of contextual shaping and influencing of individuals is general. In our understanding, we assume four main sociocultural “frames” that shape and influence eating behavior during life course. We look at chronologies of events starting in 1900 until 2020, just a few short years away. In our case, we exemplify our idea in four German women: mother, daughter, granddaughter, and great granddaughter. The mother was born in southwest Germany in 1885 and died in 1957. Her daughter was born in 1926 in southwest Germany, is now 90 years old, and still lives independently. The granddaughter was born in 1960 and, like the great granddaughter born in 1988, brought up in southwest Germany.

The mother was raised at the end of the 19th century in a setting that was incredibly different from today in respect to political systems, economic affairs, technological development, and foods available on the market. She was born in a time of monarchy and spent her young adulthood raising her own family during World War I. In her mid-50s, she experienced World War II and saw the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany when she was an old woman. She had 15 children (the oldest born in 1906, the youngest in 1929) who survived into adulthood, while the daughter, child number 14 (born in 1926), had five children (born between 1954 and 1968). The granddaughter (born 1960) had four children, while the great granddaughter, who was born in 1988, has a partner but as of yet no children. Both the mother and her still living 90-year old daughter experienced different political systems, economic crises, food scarcity events, and technological developments. Global foods were not available on the market until the rise of an affluent environment in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For the mother, cooking and preparing food was hard manual labor. She had to preserve, store, and cook food without the aid of any electrical devices. Her daughter grew up in the 1930s and 1940s with electricity, cars, modern food technology such as refrigerators, pasteurization, and deep freezers in the 1960s. Yet both women share a history of food scarcity after wars and profound “everyday competences” about how to prepare seasonal and locally produced food. They learned to value food but prepared it according to gender roles and habits to which they adhered (e.g., serving husbands first, providing meat for male family members, doing all housework without the assistance of males, training their daughters but not sons to cooking and do kitchen chores). While the daughter knows about microwave ovens and convenience food, she never learned to like or appraise them in the same way as the grand daughter. Both, mother and daughter belong to generations that learned to “make the most” of available food and to avoid food waste. Looking at the third and fourth generations, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren will experience something much different because they were born in the 1960s and late 1980s, respectively, and raised in times of food abundance, food affluence, and even food waste. Still, they are also increasingly aware of food scares and discourses on the sustainability of food production. While sustainability is a current and relevant topic for the great granddaughter, her great grandmother and grandmother also acted with an understanding of sustainability, but for different reasons: food was seen as precious and meat too expensive to waste it or serve it every day. They knew by their own experiences that food was labour intense in preparing and by no means just available. Food was bound in a value system and to waste it was regarded sinful. The experience of hunger after wars was still very present and to have enough food was seen as privilege and by no means self evident. Consuming every part of a slaughtered animal was considered essential and practical. (So-called nose-to-tail consumption of animals was merely considered normal and not worth talking about—and certainly not considered an outstanding skill as we observe today in some food blogs.) Both granddaughter and great granddaughter eat different foods than mother and daughter, eat outside the home far more often, and are familiar with globally processed foods and have integrated scarce and expensive foods more often than their great grandmother and grandmother, who had them only occasionally. Yet even in the fourth generation, some habits and food consumption patterns remain to be passed on, including family recipes and family food events. The values provided to such habits, patterns, and food values lead us to the assumption that some food patterns and behaviors have a specific trajectory within families and might be more persistent and long-lasting than previously imagined and worthy of ongoing study.

Design and Methods

To study long-term effects on nutrition behavior, we have to look at individuals’ life experience with eating and drinking. Elderly people have had daily experiences of eating and drinking for decades, and perhaps the majority of women also have daily experience with food preparation. We derived the following questions to help guide our research:

![]() Are biographical methods depicting influencing factors on nutrition behavior?

Are biographical methods depicting influencing factors on nutrition behavior?

![]() Are certain childhood eating patterns also present in adulthood?

Are certain childhood eating patterns also present in adulthood?

![]() Can we assume an intergenerational approach to better understand eating behavior?

Can we assume an intergenerational approach to better understand eating behavior?

Acquiring insight into eating biographies can follow two strategies that can be classified as quantitative versus qualitative (see Table 11.1). While quantitative methods pursue identification on causes and effects and their mechanisms, qualitative methods focus primarily on the complexity and variety of individuals’ everyday life situations (Silvermann, 2013). For this chapter, two qualitative studies will be presented.

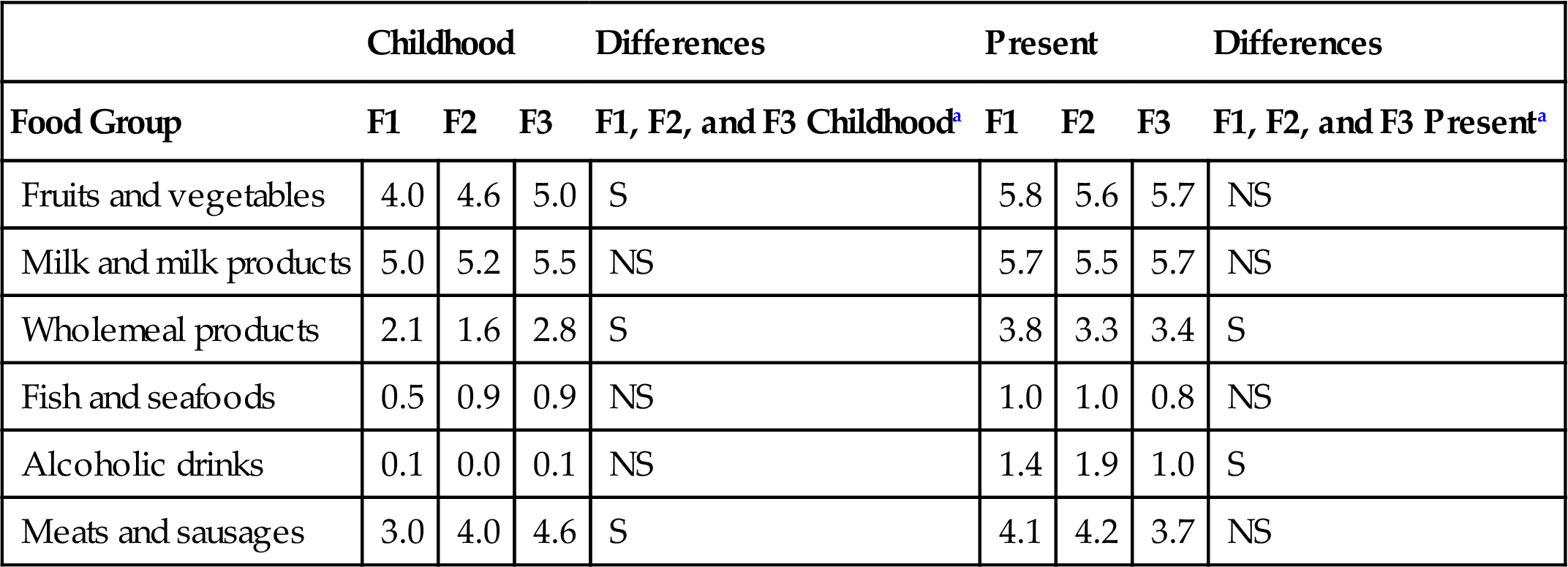

The first study is a three-generational explorative study (Brombach et al., 2014a,b) that ran from March to June 2013. Questionnaires with 31 questions on food were distributed to nutrition students at four universities in Germany and Switzerland: Karlsruhe, Jena, and Sigmaringen in Germany and Zurich, Switzerland. Questions addressed intake frequency of selected food groups, meal patterns, cooking skills, food purchasing, food storage, food packaging and handling, and attitudes about nutrition. The students were asked to fill in the questionnaires themselves (F3 generation). Whenever possible, they had to interview at least one parent (F2 generation) and one grandparent (F1 generation). All questions referred to the present and to childhood. The questions referring to current situations and childhood (up to age 14 or so) were identical so we could compare current situations with childhood situations. In total, 249 persons participated in this study (75.7% women, 24.3% men), including 53 grandparents (F1: 78 ± 6 years), 96 parents (F2: 52 ± 5 years), and 100 children (F3: 23 ± 4 years).

The participants were asked to estimate the frequency of consumption (not the amount) of six food groups in childhood and today. Mean intake frequency was based on a calculation: daily = seven days per week, four to six times = five times per week, one to three times = twice per week, one to three times per month = once per month, less than once a month = 0.5 per month, and never = zero (Table 11.2).

Table 11.2

Mean Frequency of Intake of Selected Food Groups per Week by Grandparents (F1), Parents (F2). and Children (F3) in Childhood and at Survey Time in 2013 (Intergenerational Differences)

| Childhood | Differences | Present | Differences | |||||

| Food Group | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1, F2, and F3 Childhooda | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1, F2, and F3 Presenta |

| Fruits and vegetables | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.0 | S | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | NS |

| Milk and milk products | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.5 | NS | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.7 | NS |

| Wholemeal products | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | S | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.4 | S |

| Fish and seafoods | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | NS | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | NS |

| Alcoholic drinks | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | NS | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.0 | S |

| Meats and sausages | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.6 | S | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.7 | NS |

S significant (α = 0.05),

NS not significant.

aχ2 test.

Brombach, 2014a, p. 172.

No differences were found in the frequency of intake for milk and milk products, alcoholic drinks, and fish and seafood, between the childhoods of all three generations. When focusing on the F1 generation, we could observe that, with the exemption of milk and milk products, all other food groups changed in their consumption frequency. Other result of this study refer to the cooking and food waste reduction skills (not all results are shown here; see Brombach et al., 2014a,b, for details). In both aspects, the F1 generation performed better than the F2 and F3 generations.

To get a deeper insight and understanding of the elderly, we made a “quasi control group” in a similar age group. For this we used the same questions on the frequency of food group consumptions in childhood and the present in a sample of members of the senior consumer panel—senpan—at Zurich University of Applied Sciences in Waedenswil (ZHAW), Switzerland. The consumer panel at ZHAW currently consists of 90 participants over age 62 who live independently but close to ZHAW in private homes. Most of the participants were recruited via a sensory panel or by word of mouth. This panel is not representative because it presents a healthy, well-educated, and mobile segment of Swiss seniors, and almost all senpan participants have access to the Internet. Before participating in the study, all participants had to give their written consent to participate in this survey.

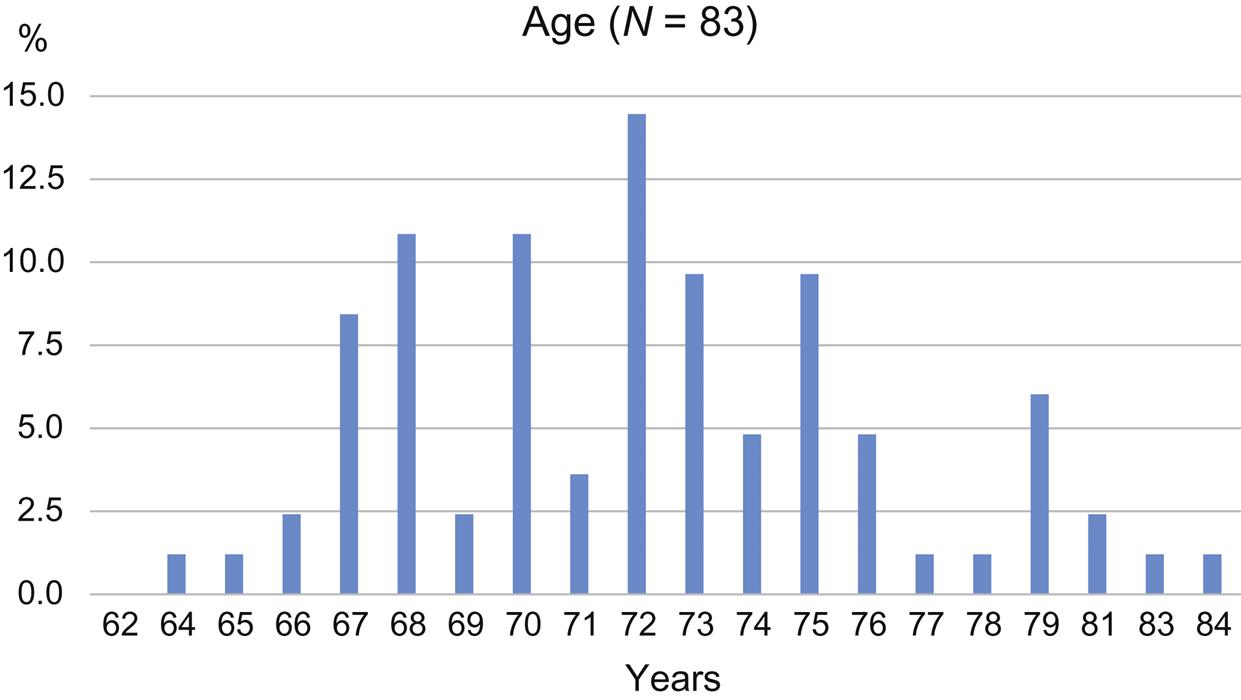

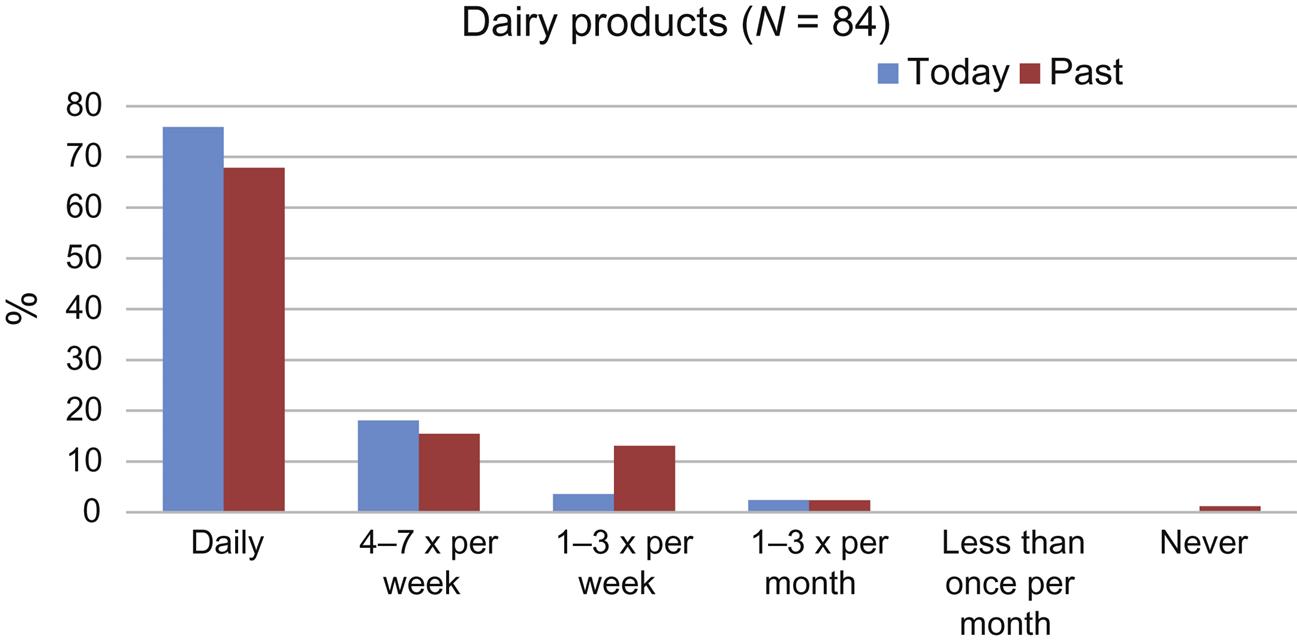

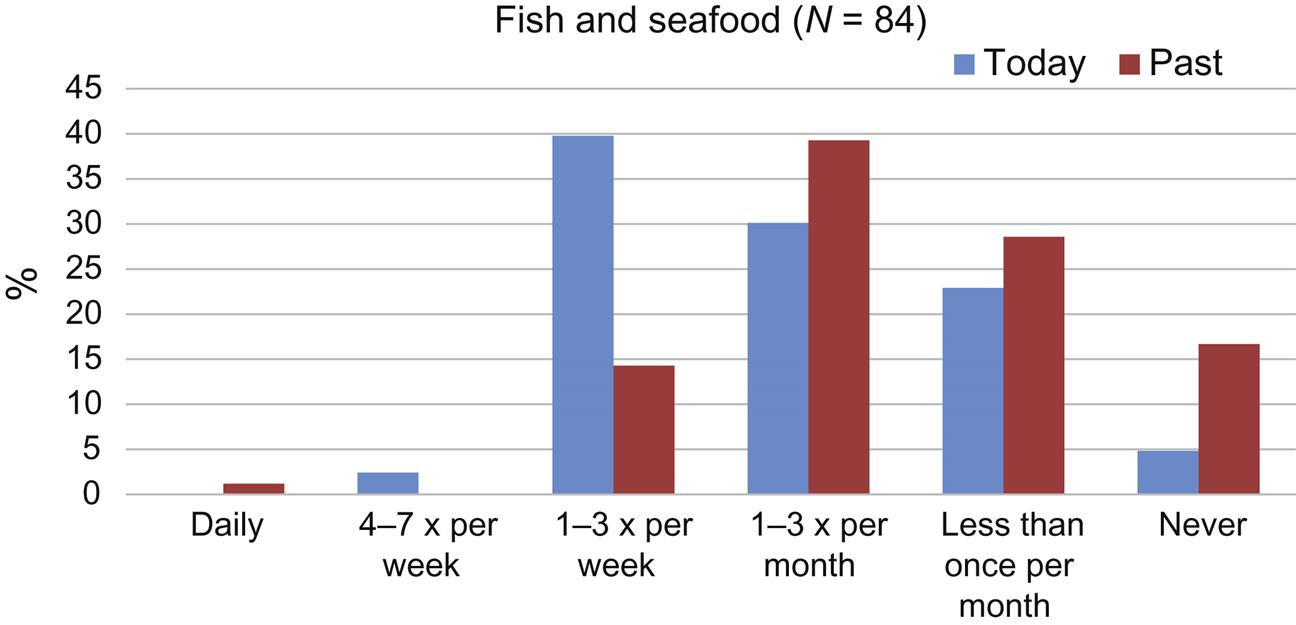

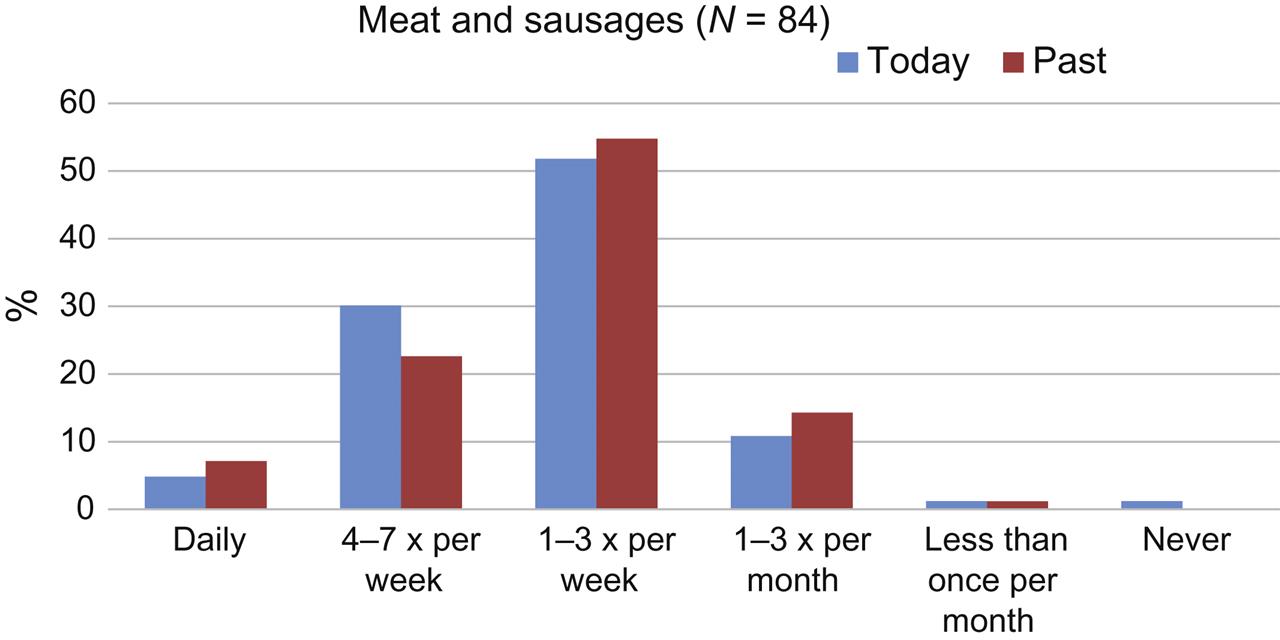

In this survey, which was conducted from March to May 2016, 84 senior consumers over age 62 participated in an online survey. The mean participant age was 72 ± 5 years and consisted of 44 men and 40 women (Fig. 11.2). In comparison to the three-generation study, results from the senpan showed surprisingly similar results. There are similar changes of frequency in all food groups except for milk and milk products. As can be seen in Figs 11.3–11.8, there are changes in today’s and past frequencies in the given food groups.

In the three-generation study, we also addressed criteria used to decide what to cook. As can be seen in Table 11.3, almost the same proportion of senpan participants selected “health” to be a prominent factor in deciding what to cook—almost in the same percentage as in the three-generation study.

Table 11.3

Criteria on What to Cook in the Three-Generation Study and Senpan Participants

| Criterion for Deciding Whether to Cook a Dish | Grandparent (F1) (n = 53) (%) | Parent (F2) (n = 96) (%) | Children (F3) (n = 100) (%) | Senpan (n = 84) (%) |

| Fast preparation | 2 | 23 | 23 | 11 |

| Another person cooks and decides | 15 | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| It has to be healthy | 38 | 29 | 21 | 35 |

| It has to be tasty | 55 | 47 | 63 | 45 |

Discussion and Applications

From the findings of the two studies, we assume that there are intergenerational effects and biographical factors that can be attributed to a given dietary behavior. We also conclude that cohort effects may lead to similar results in these two pilot studies. Because both studies are explorative, there are limitations and chances for improvement in such studies. In both these studies, there is a low number of participants and an imbalance of distribution. The recruitment may cause a bias toward health-conscious participants. Retrospective questions may be inflicted with memory bias, an issue that is hard to control for (Eisinger-Watzl et al., 2015). Results of both studies may not be generalized and should be cautiously interpreted. However, there are striking comparisons with other studies such as the German Nutrition Survey II, which shows that the significance of the health value of food and healthy food behavior increased with age. Generally, cooking skills are more prominent and better in the elderly compared to younger adults, and older Germans in general seem to know better how to handle and reuse leftovers than do younger Germans (Max-Rubner-Institut, 2008; Heuer et al., 2015). Several studies (Visser et al., 2016; Berge, 2009; Brown and Ogden, 2004; Savage et al., 2007) have found that parents influence their children‘s dietary habits and that there are similarities in the dietary behavior of parents and children. Yet studies over three generations involving grandparents have been rarely examined. Findings of biographical or intergenerational studies might be helpful to understand the onset of dietary behavior. Eating and drinking are integral parts of an upbringing, and it might be helpful to integrate questions on where people were raised to answer what, why, and how they eat. Fritz Stern, a renowned historian, used a biographical approach (Stern, 2006) to interweave historical analysis and understanding with narratives of persons in specific situations.

From the empirical data in the two studies, we can conclude that eating socialization in childhood is a distal factor molding present-day eating behavior. Including biographical aspects of eating behavior in the context of cultural, political, technological, and economic “frames” might help illuminate how, when, in what ways food is eaten today.