Chapter 1

Getting Yourself Ready for Online Investing

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Analyzing your budget and determining how much you can invest

Analyzing your budget and determining how much you can invest

![]() Taking the basic steps to get started

Taking the basic steps to get started

![]() Understanding what returns and risks you can expect from investing

Understanding what returns and risks you can expect from investing

![]() Getting to know your personal taste for risk

Getting to know your personal taste for risk

![]() Understanding your approach to investing: Passive versus active

Understanding your approach to investing: Passive versus active

![]() Finding resources online that can help you stick with a strategy

Finding resources online that can help you stick with a strategy

Before doing something risky, you probably think good and hard about what you stand to gain and what you might lose. Surprisingly, many online investors, especially those just starting out, lose that innate sense of risk and reward. They chase after the biggest possible returns without considering the sleepless nights they’ll suffer through as those investments swing up and down. Some start buying investments they’ve heard that others made money on without thinking about whether those investments are appropriate for them. Worst of all, some fall prey to fraudsters who promise huge returns in get-rich-quick schemes.

So, I’ve decided to start from the top and make sure that the basics are covered. In this chapter, you discover what you can expect to gain from investing online — and at what risk — so that you can decide whether this is for you. You also find out how to analyze your monthly budget so that you have cash to invest in the first place. Lastly, you find out what kind of investor you are by using online tools that measure your taste for risk. After you’ve become familiar with your inner investor, you can start thinking about forming an online investment plan that won’t give you an ulcer.

It’s only natural if you’re feeling skittish when it comes to investing, especially if you’re just starting out. After all, it’s been a brutal couple of decades even for veteran investors. First came the dot-com crash in 2000, then the vicious credit crunch in 2008 that threatened to drop-kick the economy, and then a nasty bear market in 2008. The stock market then proceeded to soar starting in March 2009, roughly quadrupling in value through mid-2019. But even that rally wasn't painless, because the stock market short-circuited in May 2010, due in part to computerized trading, causing its value to plunge and largely rally back in just 20 minutes. Don’t forget the 2015 Greek debt crisis and fears of a major economic slowdown in China that rattled investors. Confused yet? Get this. Even good news can hurt the market. Stocks dropped roughly 20 percent in late 2018. Why? The economy was doing so well that investors worried that the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, would slow it down.

Some think all this chaos is just too much to bear and choose to avoid stocks altogether. That decision is a mistake, though. Prudent investing can be a great way for you to reach your financial goals. You just need an approach that will maximize your returns while cutting your risks. And that’s where this book comes in.

Why Investing Online Is Worth Your While

Investing used to be easy. Your friend would recommend a broker. You’d give your money to the broker and hope for the best. But today, thanks to the explosion of web-based investment information and low-cost online trading, you get to work a lot harder by taking charge of your investments. Lucky you! So, is the additional work worth it? In my opinion, taking the time to figure out how to invest online is worthwhile because

- Investing online saves you money. Online trading is much less expensive than dealing with a broker. You’ll save tons on commissions and fees. (Say, why not invest that money you saved?)

- Investing online gives you more control. Instead of entrusting someone else to reach your financial goals, you’ll be personally involved. It’s up to you to find out about all the investments at your disposal, but you’ll also be free to make decisions.

- Investing online eliminates conflicts of interest. By figuring out how to invest and doing it yourself, you won’t have to worry about being given advice that might be in your advisors’ best interest and not yours.

Getting Started

I can’t tell you how many investors just starting out write me and ask the same question. Maybe it’s the same question that’s running through your head right now: “I want to invest, but where do I start?”

Getting started in investing seems so overwhelming that some people get confused and wind up giving up and doing nothing. Others get taken in by promises of gigantic returns and enroll in seminars, subscribe to stock-picking newsletters with dubious track records, or invest in speculative investments hoping to make money overnight, only to be disappointed. Others assume that all they need to do is open a brokerage account and start madly buying stocks. But as you’ll notice if you look at the Table of Contents or flip ahead in this book, I don’t talk about choosing a broker and opening an account until Chapter 4. You have many tasks to do before then.

However, don’t let that fact intimidate you. Check out my easy-to-follow list of things you need to do to get started. Follow these directions, and you’ll be ready to open an online brokerage account and start trading:

-

Decide how much you can save and invest.

You can’t invest if you don’t have any money, and you won’t have any money if you don’t save. No matter how much you earn, you need to set aside some cash to start investing. (Think saving is impossible? I show you digital tools later in this chapter that can help you build up savings that you can invest.)

-

Master the terms.

The world of investing has its own language. I help you to understand investingese now so that you don’t get confused in the middle of a trade when you’re asked to make a decision about something you’ve never heard of. (Chapter 2 has more on the language of online investing.)

-

Familiarize yourself with the risks and returns of investing.

You wouldn’t jump out of an airplane without knowing the risks, right? Don’t jump into investing without knowing what to expect, either. Luckily, online resources I show you later in this chapter and in Chapter 8 can help you get a feel for how markets have performed over the past 100 years. By understanding how stocks, bonds, and other investments have done, you’ll know what a reasonable return is and set your goals appropriately.

I can’t stress enough how important this step is. Investors who know how investments typically behave don’t panic — they keep their cool even during times of volatility. Panic is your worst enemy because it has a way of talking you into doing things you’ll regret later.

I can’t stress enough how important this step is. Investors who know how investments typically behave don’t panic — they keep their cool even during times of volatility. Panic is your worst enemy because it has a way of talking you into doing things you’ll regret later. -

Get a feel for how much risk you can take.

People have different goals for their money. You might already have a home and a car, in which case you’re probably most interested in saving for retirement or building an estate for your heirs. Or perhaps you’re starting a family and hope to buy a house within a year. These two scenarios call for different tastes for risks and time horizons — how long you’d be comfortable investing money before you need it. You need to know what your taste for risk is before you can invest. I show you how to measure your risk tolerance later in this chapter.

-

Understand the difference between being an active and a passive investor.

Some investors want to outsmart the market by owning stocks at just the right times or by choosing the “best” stocks. Others think doing that is impossible and don’t want the hassle of trying. At the end of this chapter, you find out how to distinguish between these two types of investors, active and passive, so that you’re in a better position to choose which one you are or want to be.

-

Find out how to turn your computer, tablet, or smartphone into a trading station.

If you have a computer, tablet or smartphone and a connection to the Internet, you have all you need to turn it into a source of constant market information. You just need to know where to look, which you find out in Chapter 2.

-

Take a dry run.

Don’t laugh. Many professional money managers have told me they got their start by pretending to pick stocks and tracking how they would have performed. It’s a great way to see whether your strategy might work, before potentially losing your shirt. You can even do this online, which I cover in Chapter 2.

-

Choose the type of account you’ll use.

You can hold your investments inside all sorts of accounts, which have different advantages and disadvantages. I cover them a little in this chapter and go into more detail in Chapter 3.

-

Set up an online brokerage account.

At last, the moment you’ve been waiting for: opening an online account. After you’ve tackled the preceding steps, you’re ready to get going. This important step is covered in Chapter 4.

-

Understand the different ways to place trades and enter orders.

In Chapter 5, I explain the many different ways to buy and sell stocks, each with very different results. (You also need to understand the tax ramifications of selling stocks, which I cover in Chapter 3.)

-

Boost your knowledge.

After you have the basics down, you’re ready to tackle the later parts of the book, where I cover advanced investing topics. These topics involve choosing an asset allocation (covered in Chapter 9), researching stocks to buy and knowing when to sell (covered in Chapter 13), and evaluating more exotic investments (the stuff you find in the bonus chapters at

www.dummies.com/bonus/onlineinvesting).

Measuring How Much You Can Afford to Invest

Online investing can help you accomplish some great things. It can help you pay for a child’s college tuition, buy the house you’ve been eyeing, retire in style, or travel to the moon. Okay, maybe not the last one. But you get the idea. Investing helps your money grow faster than inflation. And by investing online, you can profit even more by reducing the commissions and fees you must pay to different advisors and brokers.

Turning yourself into a big saver

If you want to be an investor, you must find ways to spend less money now so that you can save the excess. That means you must retrain yourself from being a consumer to being an investor. Many beginning investors have trouble getting past this point because being a consumer is so easy. Consumers buy things that they can use and enjoy now, but almost all those objects lose value over time. Cars, electronic gadgets, and clothing are all examples of things consumers “invest” their money in. You don’t even have to have money to spend — plenty of credit card companies will gladly loan it to you. Consumers fall into this spending pattern vortex and end up living paycheck to paycheck with nothing left to invest.

Investors, on the other hand, find ways to put off current consumption. Instead of spending money, they invest it into building businesses or goods and services that can earn money, rather than deplete it. The three main types of investments are stocks, bonds, and real estate; I cover others in later chapters.

Here are a few things you can do now to help you change from being a consumer to an investor:

- Start with what you can manage by putting aside a little each month.

- Keep increasing what you put aside. If you do it gradually, you won’t feel the sting of a suddenly pinched pocket.

- Hunt for deals and use coupons and discounts. Put aside the saved money.

- Buy only what you need. Don’t be fooled into buying things you don’t need because they’re on sale.

Using desktop personal finance software

The word budget is a real turnoff. It conjures up images of sitting at the kitchen table with stacks of crumpled-up receipts, trying to figure out where all your money went. As an investor who prefers to do things online, this image probably isn’t too appealing.

It’s worth your while to find other ways to see how much money is coming in and how much is going out. You can get help in many ways, including personal finance desktop software, apps, and websites.

Traditionally, the best way to track your spending and investments was personal finance software. Even today, in a world of websites and apps for smartphones and tablets, personal finance software is one of the most powerful tools for investors who want to know where every penny is going.

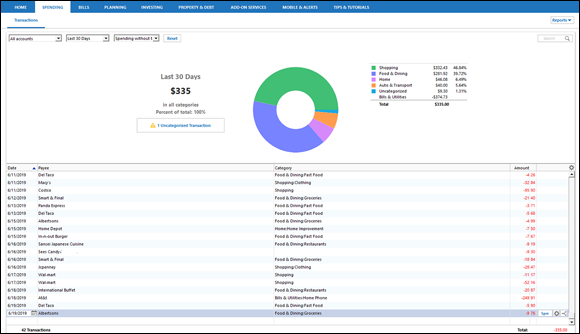

The rise in personal finance websites has narrowed the choice of personal finance software to essentially one. Quicken remains the top choice for people looking for the most powerful software to help them measure how much money they can afford to invest — and maintain privacy of their data. Quicken can help you determine how much money you spend, where it goes, and how much excess you accumulate each month that you can channel into investing. You can view the results in charts, such as the one shown in Figure 1-1.

FIGURE 1-1: Quicken allows you to slice and dice your budget and find out where your money is going.

Quicken can also create a budget for you, essentially at the click of a button. The software alerts you if you’re spending more on a certain category than you budgeted for. The biggest gripe against the software is that you have to get your transactions into it first. You can type them in, which is kind of a hassle, or you can download them from your credit card company, bank, or brokerage. Like most software these days, Quicken requires you to subscribe. It costs $60 for a two-year subscription to the Deluxe edition. Note that Quicken’s online features, including stock-quote downloads, stop working unless you renew your subscription.

Quicken does more than help you set and stick to a budget. It helps you with more advanced topics, such as managing your portfolio and taxes — stuff I cover later in this book.

Quicken might be the big kid on the block, but it isn’t completely alone. Be sure to check out these other options (some of which are free!):

- Moneydance (

www.moneydance.com) comes in versions for Windows, Macintosh, and Linux. If you’re already using Money or Quicken, no worries — Moneydance can translate your files. It’s comparably priced at $50 and offers a trial that lets you use the software until you hit 100 transactions. There’s also a version for a smartphone running iOS or Android. - Money Manager Ex (

www.codelathe.com/mmex) tries to make the power of software like Money and Quicken free. It’s open-source personal finance software, programmed by hobbyists and offered to the public as a service. If you like it, you can donate to the programmers who have created it. Money Manager Ex is also available for Android smartphones — showing how the line between personal finance software and personal finance mobile apps is blurring. - GnuCash (

www.gnucash.org) has one big thing going for it: It’s free. The software is updated and maintained by a host of freelance programmers, much like Money Manager Ex. Be warned, though, that GnuCash lacks the polish of some of the other personal finance software and is harder to navigate. Some versions of the software are considered unstable even by the programmers who coded them — at least until all the bugs are fixed. - Buddi (

http://buddi.digitalcave.ca/index.jsp) is another free option. But unlike the other personal finance software, Buddi is designed to track budgets and spending, not investment portfolios.

Perusing personal finance websites

Before you can put personal finance software to work, you often need to download and install it on your computer. You then need to spend some time figuring out how to use it. If that’s exactly the kind of thing that scared you away from making a budget in the first place, you might want to consider personal finance websites. The main benefits of personal finance websites are that they let you see your information from any PC connected to the Internet, and you generally don’t have to install software to make them work. Most personal finance websites have created mobile app versions, too, which will be discussed in the following section. But first, here are a few personal finance websites to check out:

- Mint.com (

www.mint.com) built a loyal following with its simplicity. Mint was so successful, in fact, that Intuit bought the company in 2009, shut down its own Quicken Online site, and turned Mint into its online personal finance site. Mint pulls in all your bank and brokerage accounts and imports all your financial information. For users just looking to get up and running fast, Mint is tough to beat. It’s also free. However, Mint lacks many of the powerful investment-tracking features in Quicken, including the capability to precisely track how much you paid for certain investments — your cost basis — which is important, as you discover later. And you’ll need to be comfortable handing over all your account numbers and passwords to a third party. A version of Mint for mobile devices is also worth paying attention to. - Personal Capital (

www.personalcapital.com) was built by some of the same people who created Quicken. The site is best known for its powerful investment portfolio tools, which I discuss further in Chapter 8. But Personal Capital also allows consumers to download their banking transactions and spot trends in their spending. Personal Capital provides a dashboard that shows you where all your money is coming from and going to, and a cash manager to help you keep a handle on your expenses. What’s the catch? If you use Personal Capital, you will be contacted by a financial advisor who will talk to you about signing up as a client. - YNAB (

www.youneedabudget.com) is built to make budgeting look good. With a slick website and matching app, YNAB pulls in all your spending in one place and helps you wipe out debt. You can check your progress toward saving for financial goals and join online workshops with budget counselors. The service is free for the first 34 days and then costs $6.99 a month.

If you’re not ready to trust your financial data to a website, you can still benefit from the wisdom of the web. Personal finance information sites don’t track your transactions, but they’re still able to give you the big picture. The following sites are worth checking out:

- The Financial Planning Association’s Life Goals (

www.plannersearch.org/financial-planning) lets you click financial goals, such as Saving for Retirement, and get advice. - SmartAboutMoney.org (

www.smartaboutmoney.org) provides various tips on how to save more and boost your financial strength. - The Financial Literacy and Education Commission (

www.mymoney.gov) is a government-run site that steps you through everything from saving more to avoiding frauds. It’s also a good directory of useful information available from other government agencies.

Capitalizing from personal finance apps

The rise of smartphones and tablets has given investors a new way to track their money. A large and growing group of investors see desktop personal finance software as being too clunky or complicated for them. Meanwhile, the poor performance of many websites on smartphone web browsers has led many investors to get into the habit of downloading personal finance apps to their devices to help them manage their lives. Most of the key players in personal finance apps are also leaders with personal finance websites. But because mobile apps are so important, they now deserve special treatment. The key rivals follow:

- Mint.com (

www.mint.com): Given the popularity of Mint online, it’s only natural it’s a leader in the app world, too. Mint makes sense for many consumers because it’s free and familiar; backed by a large company with the resources to update it; and available on many mobile devices including those running Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating system. The app does everything you’d expect, such as downloading balances. It also works nicely with the web — allowing you to safeguard your data if you lose a mobile device. - Mvelopes (

www.mvelopes.com) can be your spending cop, telling you when you’re spending too much. Mvelopes is a spending tracker that tries to be the digital version of envelope-based budgeting. Rather than stuffing cash in envelopes set aside for certain expenses, Mvelopes lets you decide before you get a paycheck how much you’re willing to spend in certain categories (such as dining out) and plan your spending for the month. As the month progresses, you download all your spending from banks and credit card companies and subtract each transaction from the envelopes you set aside. That way, if you’re spending too much on restaurants, for instance, you know to cut back or to skimp in other areas. It's $4 a month to sign up for the basic service, which is limited to budgeting. The Complete version allows you to get a monthly call from a financial coach to see how your plan is going. The Complete version is not a cheap tool, though, setting you back $59 a month. With the Plus version, which costs $19 a month, your financial coach calls you quarterly. Mvelopes is available for iOS and Android. - MoneyPoint (

www.microsoft.com/en-US/store/apps/MoneyPoint/9WZDNCRFJCCD) is an innovative take on mobile apps that attempts to blend the power of Quicken with the convenience of an app. Unlike Mint and other apps that rely on your entering banking information and downloading the data, MoneyPoint allows you to enter the data yourself, and your data is saved on your computer. It’s available on any devices running Windows 10, and it’s free. - Personal Capital (

www.personalcapital.com) brings its personal finance chops to the mobile app game. The app gives investors high-level and convenient access to their accounts, as well as the ability to track spending and monitor investments. The tools are free to use. Available for iOS and Android. - MoneyStrands (

www.moneystrands.com) tries to make saving your money hip, if that’s possible. The site is full of colorful diagrams, making it appear fun to use, which might make it seem less intimidating to some people. The site not only helps you track how you’re doing financially but also compares you with others and provides savings tips. MoneyStrands is available for free on iOS and Android. - Digit (

www.digit.co) aims to take the sting out of saving money. The app for iOS and Android monitors your spending and automatically calculates how much you can afford to save. The app then moves money you don’t need into a separate savings account. If you have a hole in your pocket, this might be the kick in the pants you need. But if you’re the frugal kind, you might try one of the other apps because Digit charges a monthly fee of $2.99. Paying money to save money seems a bit strange.

Saving with web-based savings calculators

If personal finance software, apps or sites seem too much like a chore or too Big Brotherish, you might consider these free web-based tools that measure how much you could save, in theory, based on a few parameters that you enter:

- MSN Money’s Savings Calculator (

www.msn.com/en-us/money/tools/savingscalculator) allows you to enter six assumptions to find out how much you'd have to save to meet a specific goal. You enter your initial deposit, annual savings amount, increase in contributions, number of years to save, what return you expect to get on your savings, and your tax bracket. The calculator does the rest of the work. - Bankrate.com’s Savings Calculator (

www.bankrate.com/calculators/savings/saving-goals-calculator.aspx) asks you what you’re saving for, be it college or buying a car. It then breaks down your financial objective and tells you how much you need to save monthly to meet said objective. - Financial Industry Regulatory Authority’s (FINRA’s) Savings Calculator (

https://tools.finra.org/savings_calculator/) lets you enter different combinations of variables, such as how much you’ve put away already and how much additional money you intend to save. It then gives you a realistic estimate of how much you can expect to add to your savings account.

Relying on the residual method

Are you the kind of person who has no idea how much money you have until you take out a wad of twenties from the ATM and check the balance on the receipt? If so, you’re probably not the budgeting type, and the previous options are too strict. For you, the best option might be to open a savings account with your bank or open a high-yield savings account and transfer in money you know you won’t need. Watch the savings account over the months and find out how much it grows. That can give you a good idea of how much you could save without even feeling it. You can find out where you can get a high rate of interest on your savings from Bankrate.com (www.bankrate.com/banking/savings/rates/). The site lists rates on savings accounts based on how much money you've saved.

Using web-based goal-savings calculators

All the previous methods help you determine how much you can save. But the following sites help you determine how much you should save to reach important goals, specifically, the ultimate goal of retirement:

- Vanguard’s Retirement Calculator (

https://personal.vanguard.com/us/insights/retirement/saving/set-retirement-goals) prompts you to enter how much you make and how long you have until retirement to help you figure out how much you need to save. Vanguard offers similar tools to help you decide how much you need to save for other goals, such as paying for a child’s college tuition. - T. Rowe Price’s Retirement Income Calculator (

www3.troweprice.com/ric/ric/public/ric.do) uses advanced computerized modeling to show you how much you need to save no matter what the stock market does. It runs your variables through a Monte Carlo simulation, which simulates what happens to your savings no matter what and gives you the odds that you’ll have enough money. - Nationwide’s On Your Side Interactive Retirement Planner (

https://isc.nwservicecenter.com/iApp/isc/rpt/launchRetirementTool.action) asks you some questions and then rates your ability to retire when and how you plan to. It also suggests tips on improving your odds of saving as much as you hope. - Index Funds Advisors Retirement Analyzer (

www.ifa.com/montecarlo/home) uses a sophisticated analysis to give you a range of possible outcomes in your retirement savings. Most retirement analyzers require you to make guesses at things such as the return you might get. The IFA Retirement Analyzer uses history to give you a good idea of what your best-case and worst-case scenarios might be.

Deciding How You Plan to Save

After you’ve determined how much you need to save and how much you can save, it’s time to put your plan into action. The way you do this really depends on how good you are at handling your money and saving. The different methods are as follows:

- Automatic withdrawals: Ever hear the cliché “pay yourself first”? It’s a trite saying that actually makes sense. The idea is that before you go shopping for that big-screen TV or start feeling rich after payday, you should set money aside for savings. Some people have the discipline to do this themselves, but many do not. For the latter group of people, the best option is to set up automatic withdrawals, which is a way of giving a brokerage firm or bank permission to automatically extract money once a month. When the money is out of your hands, you won’t be tempted to spend it.

- Retirement plans: If your goal is investing for retirement, you want to find out what retirement savings plans are available to you. If you’re an employee, you might have access to a 401(k) plan. Or if you’re self-employed, you might consider various individual retirement accounts (IRAs). When you’re starting to invest, taking advantage of available retirement plans is usually your best bet. I cover this in more detail in Chapter 3.

- On your own: If you have money left over after paying all your bills, don’t let it sit in a savings account. Leaving cash in a low-interest-bearing account is like giving a bank a cheap loan. Put your money to work for you. Brokers make it easy for you to get money to them via electronic transfers.

To Be a Successful Investor, Start Now!

The greatest force all investors have is time. Don’t waste it. The sooner you start to save and invest, the more likely you will be successful. To explain, take the example of five people, each of whom wants to have $1 million in the bank by the time he or she retires at age 65. The first investor starts when she is 20, followed by a 30-year-old, 40-year-old, 50-year-old, and 60-year-old. Assuming that each investor starts with nothing and averages 10 percent returns each year (more on this later), Table 1-1 describes how much each must save per month to reach his or her goals.

TABLE 1-1 How Much Each Must Save to Get $1 Million, Part I

|

An Investor Who Is |

Must Invest This Much Each Month to Have $1 Million at Age 65 |

|

20 years old |

$95.40 |

|

30 years old |

$263.40 |

|

40 years old |

$753.67 |

|

50 years old |

$2,412.72 |

|

60 years old |

$12,913.71 |

Note: Assumed 10% annual rate of return

See, youth has its advantages. A 20-year-old who saves less than $100 a month will end up with the same amount of money as a 60-year-old who squirrels away $12,914 a month or $154,968 a year! That’s largely due to the fact that money that’s invested early has more time to brew. And over time, the money snowballs and compounds, which is a concept I cover later in this chapter.

Learning the Lingo

Just about any profession, hobby, or pursuit has its own lingo. Car fanatics, chess players, and computer hobbyists have terms of art that they seem to learn through osmosis. Online investing is no different. You might have heard but not completely understood many terms, such as stocks and bonds. As you read through this book and browse the websites I mention, you’ll probably periodically stumble on unfamiliar words.

Don’t expect a standard dictionary to help much. Investing terms can be so specialized and precise that your dusty ol' Webster's dictionary might not be a big help. Fortunately, a number of excellent online investing glossaries explain in detail what investing terms mean. Here are few for you to check out:

- Investopedia (

www.investopedia.com) has one of the most comprehensive databases of investing terms, with more than 5,000 entries. The site not only covers the basics but also explains advanced terms in great detail. It’s also fully searchable so that you don’t waste time getting the answer. - Harvey’s Hypertextual Finance Glossary (

people.duke.edu/~charvey/Classes/wpg/glossary.htm) is all about quick answers. The database, written by Campbell Harvey, a professor of finance at Duke University, explains most basic investment terms in one or two sentences. - InvestorWords (

www.investorwords.com) has a fully searchable database of investment terms, but it also makes the dictionary a bit more interesting with unique features such as a term of the day and a summary of terms that have recently rewritten definitions. - The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Glossary (

www.investor.gov/additional-resources/general-resources/glossary) is operated by the government agency primarily responsible for overseeing most investing activity. The title doesn’t disappoint. You’ll find quick descriptions of all the basics and also some more advanced industry topics.

Setting Your Expectations

Have you ever talked to a professional investor or financial advisor? One of the first things you’ll hear is how much experience he or she has. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been told, “I’ve been on Wall Street for 30 years. I’ve seen it all.”

Some of that is certainly old-fashioned bragging. But these claims are common because in investing, experience does count. It’s easy to say you could endure a bear market until you’re watching, white-knuckled and sweating bullets, as your nest egg shrivels from $100,000 to $80,000 or $50,000. Experience brings perspective, which is very important.

But if you’re new to investing, don’t despair. Online tools can help you develop the brain of a grizzled Wall Street sage. And don’t forget that I’m here to set you straight as well. In fact, I’m set to start talking about how much you can expect to make from investing. And you’ll be hearing a great deal about a little something called the rate of return.

Keeping up with the rate of return

Don’t let the term rate of return scare you. It’s the most basic concept in investing, and you can master it. Just remember that it’s the amount, measured as a percent, that your investment increases in value in a certain period of time. If you have a savings account, you understand the concept already. If you put $100 in a bank account paying 2.5 percent interest, you know that by the end of the year, you will have received $2.50 in interest. You earned a 2.5 percent annual rate of return. Rates of return are useful in investing because they work as a report card to tell investors how well an investment is doing, no matter how much money is invested.

You can calculate rates of return yourself with the following:

- A formula: Subtract an asset’s previous value from its current value, divide the difference by the asset’s previous value, and multiply by 100. If a stock rises from $15 to $32 a share, you would calculate the rate of return by first subtracting 15 from 32 to get 17. Next, divide 17 by 15 and multiply by 100. The rate of return is 113.3 percent.

- Financial calculator: You can use the Hewlett-Packard 12c calculator, which financial types always carry. Find out how to crunch a rate of return with an easy-to-follow tutorial at

http://h20331.www2.hp.com/Hpsub/downloads/HP12Cpercents.pdf. (Look for Example 5.) - Financial website: Many handy sites can calculate rates of return for you, including CalcXML (

www.calcxml.com/calculators/rate-of-return-calculator) and Bankrate (www.bankrate.com/calculators/retirement/roi-calculator.aspx).

The power of compounding

Famous physicist Albert Einstein once called compounding the most powerful force in the universe. Compounding is when money you invest earns a return and then that return also earns a return. (Dizzy yet?) When you leave money invested for a long time, the power of compounding kicks in.

Imagine that you’ve deposited $100 in an account that pays 2.5 percent in interest a year. In the first year, you’d earn $2.50 in interest, which brings your balance to $102.50. But in the second year, you’d earn interest of $2.56. Why? Because you’ve also earned 2.5 percent on the $2.50 in interest you earned. The longer you’re invested, the more time your money has to compound.

Compounding works on your side to fight against inflation. Calculator Pro has a web-based calculator (www.calculatorpro.com/calculator/real-rate-of-return-calculator) that tells you whether your rate of return is keeping you ahead of inflation. The calculator also tells you what your real rate of return is — in other words, how much of your return isn't being eaten away by inflation.

Determining How Much You Can Expect to Profit

Why bother investing online? To make money, of course. But how much do you want to make? Understanding what you can expect to earn is where you need to start. Whenever you hear about an investment and what kinds of returns it promises, you should be able to mentally compare it with the kinds of returns you can expect from stocks, bonds, and other investments. That way, you know whether the returns you’re being promised are too good to be true.

How do you do this? By relying on the hard work of academics who have done some heavy lifting. Academics and market research firms have ranked investments by how well they’ve done over the years. And I’m not just talking a few years, but decades — in many cases, going back to the 1920s and earlier. The amount of work that’s gone into measuring historical rates of returns is staggering, but if you’re using online resources, you’re just a click away from finding out how most types of assets have done.

What you expect to earn is a number that can affect most of your investment decisions, usually dramatically. The following table is a revised version of Table 1-1 — the one that showed how five different people could expect to save $1 million. Table 1-2 looks at how much they must save to make their goal changes based on how much they think they will earn from their investments.

TABLE 1-2 How Much Each Must Save to Get $1 Million, Part II

|

An Investor Who Is |

Must Invest This Much Each Month if She Earns 5% |

Must Invest This Much Each Month if She Earns 10% |

Must Invest This Much Each Month if She Earns 15% |

|

20 years old |

$493.48 |

$95.40 |

$15.28 |

|

30 years old |

$880.21 |

$263.40 |

$68.13 |

|

40 years old |

$1,679 |

$753.67 |

$308.31 |

|

50 years old |

$3,741 |

$2,412.72 |

$1,495.87 |

|

60 years old |

$14,704.57 |

$12,913.71 |

$11,289.93 |

The 20-year-old must save nearly $500 a month extra if she thinks she will earn only 5 percent a year from her investments instead of 15 percent. But even scarier, if she saves $15.28 thinking she’ll earn 15 percent a year, but earns only 5 percent, she’ll have just $30,963 instead of the $1 million she was counting on.

Studying the past

When people ask you how stocks are doing, they often want to know how much they went up or down that day. Financial TV stations and websites reinforce this preoccupation with the here-and-now by scrolling second-by-second moves in stock prices across the bottom of the screen.

But, second-by-second moves in stocks don’t tell you much. If a stock goes down a bit and a company didn’t report the news, did anything change during that second? Watching short-term movements of stock prices doesn’t mean much in the overall scheme of things.

To understand how investments behave, it’s more helpful to analyze their movements over as many years as you can. That way, recessions are blended with boom times to get you to a real, smooth average. Doing this requires the painstaking method of processing dozens of annual returns of stocks and analyzing the data. Luckily, some academics and industry pioneers have done much of the work for you, and you can access their findings if you know where to look. And I just happen to know a few places where you can start your search:

-

Bogle Financial Market Research (

www.vanguard.com/bogle_site/bogle_home.html) is the website maintained by the founder of Vanguard, John C. Bogle. Bogle revolutionized the investment industry by creating the world’s largest index mutual fund, the Vanguard 500, which is designed to replicate the performance of the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock market index. Stock market indexes, such as the Standard & Poor’s 500 index and Dow Jones Industrial Average, are benchmarks that let you track how the market is doing.Bogle passed away in 2019, but his site is still invaluable because he explained that the market, on average, returns about 10 percent a year. That benchmark will be important later as you evaluate different stocks. Indexes are covered in more detail in Chapter 8.

- Annual Returns on Stock, T. Bonds and T. Bills: 1928 – Current (

pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html) doesn’t have the catchiest title, but it’s great information for investors. The site, maintained by New York University Professor Aswath Damodaran, lets you see how stocks and bonds have done every year since 1928. This is one site you’ll want to bookmark. - FTSE Russell’s US Index Performance Calculator (

www.ftserussell.com/index-series/index-tools/russell-index-performance-calculator) lets you look up how all types of stocks, ranging from small to large, in addition to bonds, have done over the years. You’ll find a handy Index Returns Calculator that lets you see how different types of stocks have done at different points in history. FTSE Russell provides a variety of market indexes, or measuring sticks for the various markets. - Kenneth R. French’s website at

http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html#HistBenchmarks. This site is complicated but worth the effort. French, a professor at Dartmouth, along with University of Chicago’s Eugene Fama (faculty.chicagobooth.edu/eugene.fama), revolutionized investing with an analysis that found that essentially three things move stocks: what the general market is doing, how big the company is, and how pricey the shares are. Both profs keep statistics on their sites on how stocks move. - Index Funds Advisors (

www.ifa.com) compiles much of the research done by Fama and French and helps explain it in plain language. You can download a colorful book from the site, Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors, by Mark T. Hebner (IFA). The book explains how different types of stocks perform in the long term and shows how much you can expect to gain. It also shows long-term returns of bonds. You can also calculate the information yourself using the IFA Index Calculator (www.ifa.com/calculator/?i=port100_ifa&g=100000&s=1/1/2000&e=7/31/2015&gy=true&aorw=false&perc=true). Figure 1-2 shows you what kind of data this calculator can churn out. - Robert Shiller’s website (

www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller) contains exhaustive data on how markets have done over the long term. You can view the data and make your own conclusions. Shiller is a well-known economics professor at Yale University. - S&P Indices (

us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500) contains a full record of the returns from the Standard & Poor’s 500 index going back for decades. This is invaluable data because you can understand how markets tend to move, instead of worrying about things that have never happened. Click the down arrow to the right of the Additional Info button. Scroll down and click the S&P Market Attributes Web File link, which then prompts you to open an Excel file. Click the Prices-Annual tab and scroll down the spreadsheet’s annual returns. That information can give you an idea of how volatile stocks can be and also what returns are possible if you stay invested. - FreeStockCharts.com (

www.freestockcharts.com/legacy) allows you to download the stock trading history of most investments. After the site loads, just start typing the name or symbol of the investment you’re interested in. A box will pop up with the names of stocks that match what you entered. Click the name of the company you’re interested in. If you click the Export Chart icon (two small cylinders) along the top of the chart, you can download data into Excel. The site keeps data on most stocks going back to 1985. The site works with only the Internet Explorer web browser and requires the Silverlight plug-in. - Yahoo! Finance (

http://finance.yahoo.com) is a well-known source for historical stock data, and for good reason. You can download historical prices on many stocks going back to their first days of trading. And downloads are free. In the Search for News, Symbols or Companies field, just enter the symbol of the stock you’re interested in and click the magnifying glass button. Then click the Historical Prices link in the center of the page. If you want to download the data, click the Download Data link.

FIGURE 1-2: IFA.com’s Index Calculator allows you to get detailed information on how different types of investments have performed over the years.

What the past tells you about the future

Exhaustive studies of markets have shown that stocks, in general, return about 10 percent a year. Through the years, 10 percent returns have been the benchmark for long-term performance, making them a good measuring stick for you and something to help you keep your bearings. But long-term studies of securities also show that, to get higher returns, you usually must also accept more risk. Table 1-3 shows how investors must often accept more risk to get a higher return.

TABLE 1-3 No Pain, No Gain

|

Investment |

Average Annual Return |

Relative Risk |

|

Stocks |

10.0% (based on S&P 500 since 1926) |

Riskiest |

|

Corporate bonds |

6.0% |

Moderately risky |

|

Treasury bills (loans to the U.S. government that come due in a year or less) |

3.4% |

Least risky |

Source: Morningstar through 2018

Table 1-4 shows you just how crazy the market’s movements can be in the short term, using the history of the popular Standard & Poor’s 500 index since 1928.

TABLE 1-4 Wild Days for the S&P 500

|

Event |

Amount |

|

Number of days up |

12,447 (average gain 0.74%) |

|

Number of days down |

11,017 (average loss 0.78%) |

|

Best one-day percentage gain |

March 15, 1933, up 16.6% |

|

Worst one-day percentage loss |

Oct. 19, 1987, down 20.5% |

|

Best year |

1933, up 46.6% |

|

Worst year |

1931, down 47.1% |

|

Best month |

April 1933, up 42.2% |

|

Worst month |

Sept. 1931, down 29.9% |

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices as of the end of 2018

Gut-Check Time: How Much Risk Can You Take?

It’s time to get a grip — a grip on how much you can invest, that is. Most beginning investors are so interested in finding stocks that make them rich overnight that they lose sight of risk. But academic studies show that risk and return go hand in hand. That’s why you need to know how much risk you can stomach before you start looking for investments and buying them online.

Several excellent online tools can help you get a handle on how much of a financial thrill seeker you are. Most are structured like interviews that ask you a number of questions and help you decide how much volatility you can comfortably stomach. These interviews are kind of like personality tests for your investment taste. I cover several in more detail in Chapter 9, where I discuss how to create an investing road map, called an asset allocation. For now, answering these questionnaires right away is worthwhile so that you can understand what kind of investor you are:

- Vanguard’s Investor Questionnaire (

https://personal.vanguard.com/us/FundsInvQuestionnaire) asks ten salient questions to determine how much of a risk taker you are with your money. It determines your ideal asset allocation. Take note of the breakdown. The closer to 100 percent that Vanguard recommends you put in stocks, the more risk-tolerant you are, and the closer to 100 percent in bonds, the less risk-tolerant you are. - Index Funds Advisors Risk Capacity Survey (

www.ifa.com/SurveyNET/index.aspx) offers a quick risk survey that can tell you what kind of investor you are after answering just five questions. You can also find a complete risk capacity survey that hits you with a few dozen questions. Whichever you choose, the survey can characterize what kind of investor you are and even display a painting that portrays your risk tolerance. - Charles Schwab Investor Profile Questionnaire (

www.schwab.com/public/file/P-778947/InvestorProfileQuestionnaire.pdf) gets you to think about the factors that greatly determine how you should be investing, such as your investment time horizon and tolerance for risk. The Schwab questionnaire can be printed so you don't have to be in front of a computer to take it. At the bottom of the questionnaire is a chart that helps you see how aggressive or conservative you should be with your portfolio.

Passive or Active? Deciding What Kind of Investor You Plan to Be

Investing might not seem controversial, but it shouldn’t surprise you that anytime you’re talking about money, people have some strong opinions about the right way to do things. The first way investors categorize themselves is by whether they are passive or active. Because these two approaches are so different, the following sections help you think about what they are and which camp you see yourself in. Where you stand not only affects which broker is best for you, as discussed in Chapter 4, but also affects which chapters in this book appeal to you most.

How to know if you’re a passive investor

Passive investors don’t try to beat the stock market. They merely try to keep up with it by owning all the stocks in an index. An index is a basket of stocks or bonds that track a market by measuring movement by all the investments in it. For instance, the S&P 500 index tracks a selection of the largest and most valuable 500 U.S. stocks. Passive investors are happy matching the market’s performance, knowing that they can try to boost their real returns with a few techniques I discuss in Chapter 9.

You know you’re a passive investor if you

- Aren’t interested in choosing individual stocks: These investors buy large baskets of stocks that mirror the performance of popular stock indexes such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average or the Standard & Poor’s 500 index. Passive investors don’t worry if a small upstart company they invested in will release its new product on time and whether it will be well received. They typically own small pieces of hundreds of stocks instead.

- Want to own mutual and exchange-traded funds: Because passive investors aren’t looking for the next Microsoft, Facebook, or Apple, they buy mutual and exchange-traded funds that buy hundreds of stocks. (I cover mutual and exchange-traded funds in more detail in Chapters 10 and 11, respectively.)

- Want to reduce taxes: Passive investors tend to buy investments and forget about them until many years later when they need the money. This approach can be lucrative because by holding onto diversified investments for a long time and not selling them, passive investors can postpone when they have to pay capital gains taxes. (I cover capital gains taxes in more detail in Chapter 3.)

- Do not want to stress about stocks’ daily, monthly, or even annual movements: Passive investors tend to buy index or mutual funds and forget about them. They don’t need to sit in front of financial TV shows, surf countless financial websites, read magazines, or worry about where stocks are moving. They’re invested for the long term, and everything else is just noise to them.

Sites for passive investors to start with

One of the toughest things about being a passive investor is sitting still during a bull market when everyone else seems to be making more than you. Yes, you might be able to turn off the TV, but inevitably you’ll bump into someone who brags about his or her giant gains and laughs at you for being satisfied with 10 percent average annual market returns.

When that happens, it’s even more important to stick with your philosophy. Following the crowd at this moment undermines the value of your strategy. That’s why even passive investors are well served going to websites where other passive investors congregate:

- Bogleheads (

www.bogleheads.org) is an electronic water cooler for fans of Vanguard index funds and passive investors to meet, encourage, and advise each other. They call themselves Bogleheads in honor of the founder of Vanguard, John Bogle. - The Arithmetic of Active Management (

www.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/active/active.htm) is a reprint of an article by an early proponent of passive investing, William Sharpe, who explains why active investing can never win. - Vanguard (

www.vanguard.com) contains many helpful stories about the power of index investing and offers them for free, even if you don’t have an account.

How to know whether you’re an active investor

Active investors almost feel sorry for passive investors. Why would anyone be satisfied just matching the stock market and not even try to do better? Active investors feel that if you’re smart enough and willing to spend time doing homework, you can exceed 10 percent annual returns. Likewise, active investors question the logic of holding stocks even as markets plunge. Active investors also find investing to be thrilling, almost like a hobby. Some active investors try to find undervalued stocks and hold them until they’re discovered by other investors. Another class of active investors are short-term traders, who bounce in and out of stocks trying to get quick gains.

You’re an active investor if you

- Think long-term averages of stocks are meaningless: Active investors believe they can spot winning companies that no one knows about yet or are underappreciated, buy their shares at just the right time, and sell them for a profit.

- Are willing to spend large amounts of time searching for stocks: These are the investors who sit in front of financial TV shows, analyze stocks that look undervalued, and do all sorts of prospecting trying to find gems.

- Believe they can hire mutual fund managers who can beat the market: Some active investors think that certain talented mutual fund managers are out there and that if they just give their money to those managers, they’ll win.

- Suspect certain types of stocks aren’t priced correctly and many investors make bad decisions: Active investors believe they can outsmart the masses and routinely capitalize on the mistakes of the great unwashed.

- Understand the risks: Most active traders underperform index funds, some without even realizing it. Before deciding to be an active trader, be sure to test out your skills with online simulations, as I describe in Chapter 2, or make sure that you’re measuring your performance correctly, as I describe in Chapter 8. If you’re losing money picking stocks, stop doing it. Be sure to know how dangerous online investing can be when trying to be an active investor by reading a warning from the Securities and Exchange Commission here:

http://sec.gov/investor/pubs/onlinetips.htm.

Sites for the active investor to start with

Ever hear of someone trying to learn a foreign language by moving to the country and picking it up through immersion? The idea is that by just being around the language, and through the necessity of buying food or finding the restroom, the person eventually gets proficient.

If you’re interested in active investing, you can do the same thing by hitting websites that are common hangouts for active investors, picking up how these types of investors find stocks that interest them and trade on them. These sites can show you the great pains active investors go through in their attempt to beat the market. A few to start looking at follow:

- TheStreet.com (

www.thestreet.com) collects trading ideas and tips from writers mainly looking for quick-moving stocks and other investments. - Investor’s Business Daily (

www.investors.com) provides tools and research for investors looking for promising stocks. The site highlights stocks that have moved up or down by a large amount, which usually catches the attention of traders. - Seeking Alpha (

http://seekingalpha.com) provides news and commentary for investors of all skill levels who are trying to beat the market.

Some investors prefer creating a spreadsheet to track all their finances. Microsoft provides several helpful budgeting spreadsheets, which you can find by entering the word budget in the search field of the Office Templates & Themes home page (

Some investors prefer creating a spreadsheet to track all their finances. Microsoft provides several helpful budgeting spreadsheets, which you can find by entering the word budget in the search field of the Office Templates & Themes home page ( Putting all your financial data online with a third party is simple and convenient, but it can be a bad idea for some investors. First, there are security concerns with entrusting all your financial data to strangers over the Internet. Every year, hundreds of companies’ sites are breached and their data compromised. Even giant companies such as retailer Target, credit-rating service Equifax, and hotel chain Marriott lost customer data in breaches. But beyond that, if a website calls it quits one day, you might lose access to the historical financial and investing records you kept on the site. For example, Wesabe had been a leading online financial tracking site until it pulled the plug in July 2010. The investment-tracking site Cake Financial was bought by E*TRADE in January 2010 and, without warning, shut down — leaving investors without access to their financial information. Geezeo had been a leading online financial tracker website until the company shut down its public website in 2010 and moved to sell its products to banks instead. These examples are a big reason why personal financial software, such as Quicken, can still be preferable because your data is stored on your computer’s hard drive, where you can always access it (unless it fatally crashes, and you failed to maintain a current backup copy, of course).

Putting all your financial data online with a third party is simple and convenient, but it can be a bad idea for some investors. First, there are security concerns with entrusting all your financial data to strangers over the Internet. Every year, hundreds of companies’ sites are breached and their data compromised. Even giant companies such as retailer Target, credit-rating service Equifax, and hotel chain Marriott lost customer data in breaches. But beyond that, if a website calls it quits one day, you might lose access to the historical financial and investing records you kept on the site. For example, Wesabe had been a leading online financial tracking site until it pulled the plug in July 2010. The investment-tracking site Cake Financial was bought by E*TRADE in January 2010 and, without warning, shut down — leaving investors without access to their financial information. Geezeo had been a leading online financial tracker website until the company shut down its public website in 2010 and moved to sell its products to banks instead. These examples are a big reason why personal financial software, such as Quicken, can still be preferable because your data is stored on your computer’s hard drive, where you can always access it (unless it fatally crashes, and you failed to maintain a current backup copy, of course).