CHAPTER 9

Virtual Memory

In Chapter 8, we discussed various memory-management strategies used in computer systems. All these strategies have the same goal: to keep many processes in memory simultaneously to allow multiprogramming. However, they tend to require that an entire process be in memory before it can execute.

Virtual memory is a technique that allows the execution of processes that are not completely in memory. One major advantage of this scheme is that programs can be larger than physical memory. Further, virtual memory abstracts main memory into an extremely large, uniform array of storage, separating logical memory as viewed by the user from physical memory. This technique frees programmers from the concerns of memory-storage limitations. Virtual memory also allows processes to share files easily and to implement shared memory. In addition, it provides an efficient mechanism for process creation. Virtual memory is not easy to implement, however, and may substantially decrease performance if it is used carelessly. In this chapter, we discuss virtual memory in the form of demand paging and examine its complexity and cost.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

- To describe the benefits of a virtual memory system.

- To explain the concepts of demand paging, page-replacement algorithms, and allocation of page frames.

- To discuss the principles of the working-set model.

- To examine the relationship between shared memory and memory-mapped files.

- To explore how kernel memory is managed.

9.1 Background

The memory-management algorithms outlined in Chapter 8 are necessary because of one basic requirement: The instructions being executed must be in physical memory. The first approach to meeting this requirement is to place the entire logical address space in physical memory. Dynamic loading can help to ease this restriction, but it generally requires special precautions and extra work by the programmer.

The requirement that instructions must be in physical memory to be executed seems both necessary and reasonable; but it is also unfortunate, since it limits the size of a program to the size of physical memory. In fact, an examination of real programs shows us that, in many cases, the entire program is not needed. For instance, consider the following:

- Programs often have code to handle unusual error conditions. Since these errors seldom, if ever, occur in practice, this code is almost never executed.

- Arrays, lists, and tables are often allocated more memory than they actually need. An array may be declared 100 by 100 elements, even though it is seldom larger than 10 by 10 elements. An assembler symbol table may have room for 3,000 symbols, although the average program has less than 200 symbols.

- Certain options and features of a program may be used rarely. For instance, the routines on U.S. government computers that balance the budget have not been used in many years.

Even in those cases where the entire program is needed, it may not all be needed at the same time.

The ability to execute a program that is only partially in memory would confer many benefits:

- A program would no longer be constrained by the amount of physical memory that is available. Users would be able to write programs for an extremely large virtual address space, simplifying the programming task.

- Because each user program could take less physical memory, more programs could be run at the same time, with a corresponding increase in CPU utilization and throughput but with no increase in response time or turnaround time.

- Less I/O would be needed to load or swap user programs into memory, so each user program would run faster.

Thus, running a program that is not entirely in memory would benefit both the system and the user.

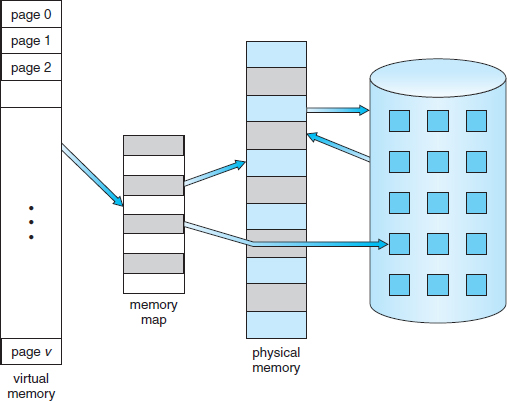

Virtual memory involves the separation of logical memory as perceived by users from physical memory. This separation allows an extremely large virtual memory to be provided for programmers when only a smaller physical memory is available (Figure 9.1). Virtual memory makes the task of programming much easier, because the programmer no longer needs to worry about the amount of physical memory available; she can concentrate instead on the problem to be programmed.

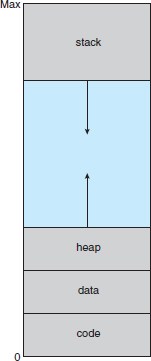

The virtual address space of a process refers to the logical (or virtual) view of how a process is stored in memory. Typically, this view is that a process begins at a certain logical address—say, address 0—and exists in contiguous memory, as shown in Figure 9.2. Recall from Chapter 8, though, that in fact physical memory may be organized in page frames and that the physical page frames assigned to a process may not be contiguous. It is up to the memory management unit (MMU) to map logical pages to physical page frames in memory.

Figure 9.1 Diagram showing virtual memory that is larger than physical memory.

Note in Figure 9.2 that we allow the heap to grow upward in memory as it is used for dynamic memory allocation. Similarly, we allow for the stack to grow downward in memory through successive function calls. The large blank space (or hole) between the heap and the stack is part of the virtual address space but will require actual physical pages only if the heap or stack grows. Virtual address spaces that include holes are known as sparse address spaces. Using a sparse address space is beneficial because the holes can be filled as the stack or heap segments grow or if we wish to dynamically link libraries (or possibly other shared objects) during program execution.

Figure 9.2 Virtual address space.

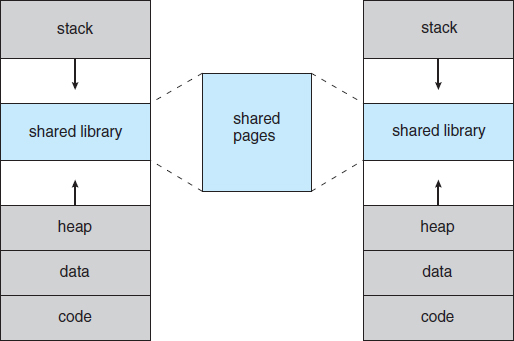

Figure 9.3 Shared library using virtual memory.

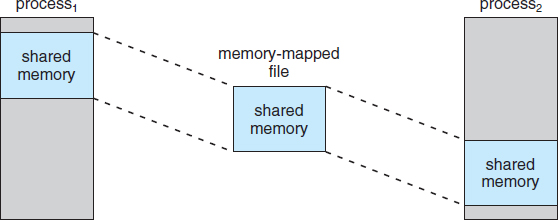

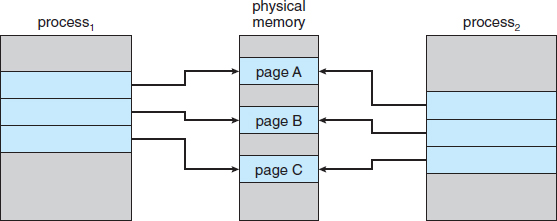

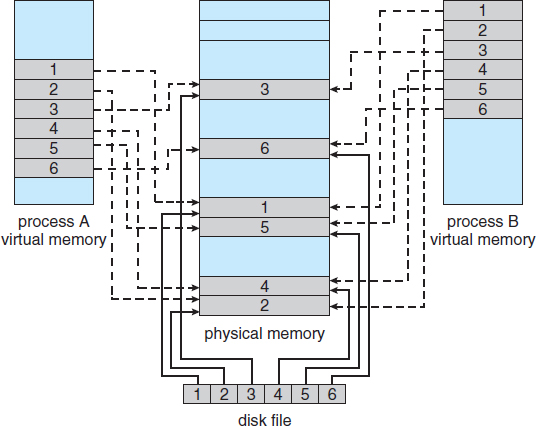

In addition to separating logical memory from physical memory, virtual memory allows files and memory to be shared by two or more processes through page sharing (Section 8.5.4). This leads to the following benefits:

- System libraries can be shared by several processes through mapping of the shared object into a virtual address space. Although each process considers the libraries to be part of its virtual address space, the actual pages where the libraries reside in physical memory are shared by all the processes (Figure 9.3). Typically, a library is mapped read-only into the space of each process that is linked with it.

- Similarly, processes can share memory. Recall from Chapter 3 that two or more processes can communicate through the use of shared memory. Virtual memory allows one process to create a region of memory that it can share with another process. Processes sharing this region consider it part of their virtual address space, yet the actual physical pages of memory are shared, much as is illustrated in Figure 9.3.

- Pages can be shared during process creation with the fork() system call, thus speeding up process creation.

We further explore these—and other—benefits of virtual memory later in this chapter. First, though, we discuss implementing virtual memory through demand paging.

9.2 Demand Paging

Consider how an executable program might be loaded from disk into memory. One option is to load the entire program in physical memory at program execution time. However, a problem with this approach is that we may not initially need the entire program in memory. Suppose a program starts with a list of available options from which the user is to select. Loading the entire program into memory results in loading the executable code for all options, regardless of whether or not an option is ultimately selected by the user. An alternative strategy is to load pages only as they are needed. This technique is known as demand paging and is commonly used in virtual memory systems. With demand-paged virtual memory, pages are loaded only when they are demanded during program execution. Pages that are never accessed are thus never loaded into physical memory.

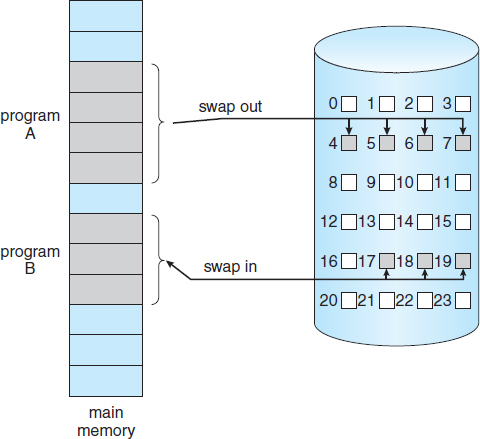

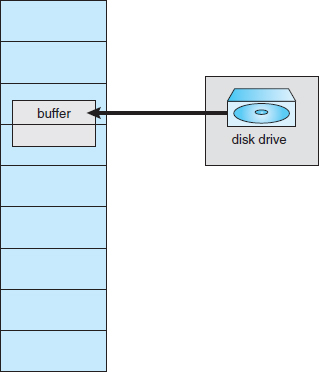

A demand-paging system is similar to a paging system with swapping (Figure 9.4) where processes reside in secondary memory (usually a disk). When we want to execute a process, we swap it into memory. Rather than swapping the entire process into memory, though, we use a lazy swapper. A lazy swapper never swaps a page into memory unless that page will be needed. In the context of a demand-paging system, use of the term “swapper” is technically incorrect. A swapper manipulates entire processes, whereas a pager is concerned with the individual pages of a process. We thus use “pager,” rather than “swapper,” in connection with demand paging.

Figure 9.4 Transfer of a paged memory to contiguous disk space.

9.2.1 Basic Concepts

When a process is to be swapped in, the pager guesses which pages will be used before the process is swapped out again. Instead of swapping in a whole process, the pager brings only those pages into memory. Thus, it avoids reading into memory pages that will not be used anyway, decreasing the swap time and the amount of physical memory needed.

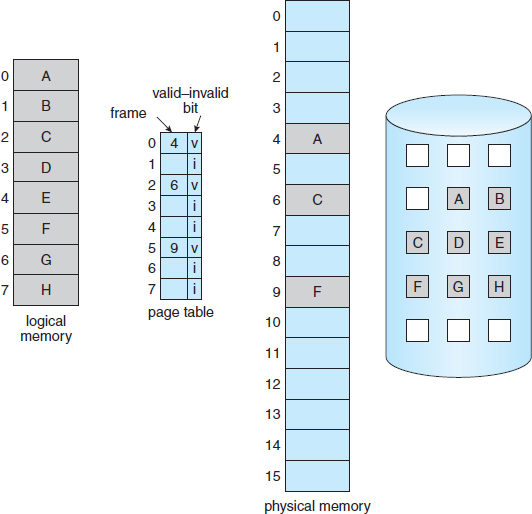

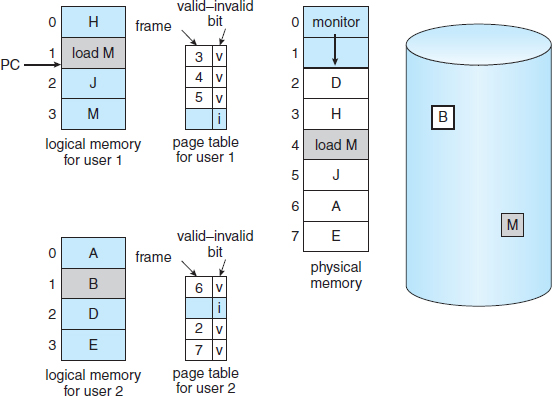

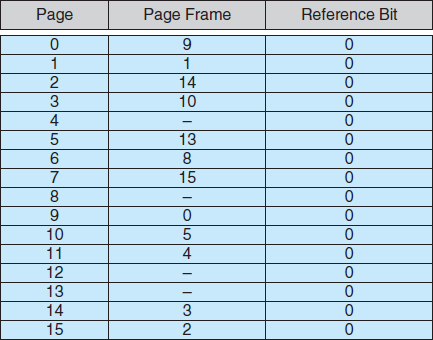

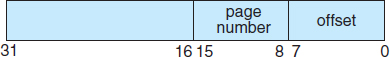

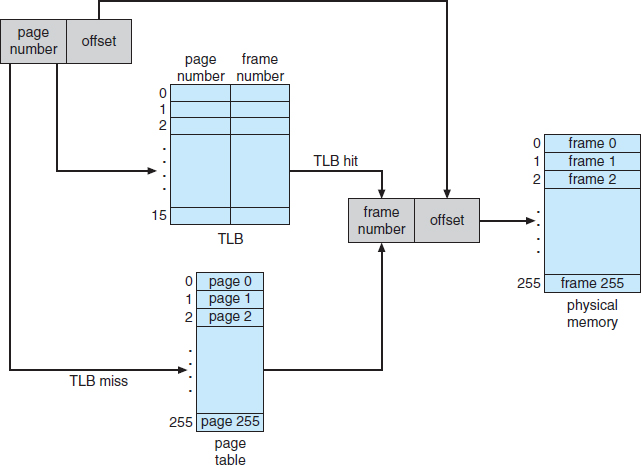

With this scheme, we need some form of hardware support to distinguish between the pages that are in memory and the pages that are on the disk. The valid–invalid bit scheme described in Section 8.5.3 can be used for this purpose. This time, however, when this bit is set to “valid,” the associated page is both legal and in memory. If the bit is set to “invalid,” the page either is not valid (that is, not in the logical address space of the process) or is valid but is currently on the disk. The page-table entry for a page that is brought into memory is set as usual, but the page-table entry for a page that is not currently in memory is either simply marked invalid or contains the address of the page on disk. This situation is depicted in Figure 9.5.

Notice that marking a page invalid will have no effect if the process never attempts to access that page. Hence, if we guess right and page in all pages that are actually needed and only those pages, the process will run exactly as though we had brought in all pages. While the process executes and accesses pages that are memory resident, execution proceeds normally.

Figure 9.5 Page table when some pages are not in main memory.

Figure 9.6 Steps in handling a page fault.

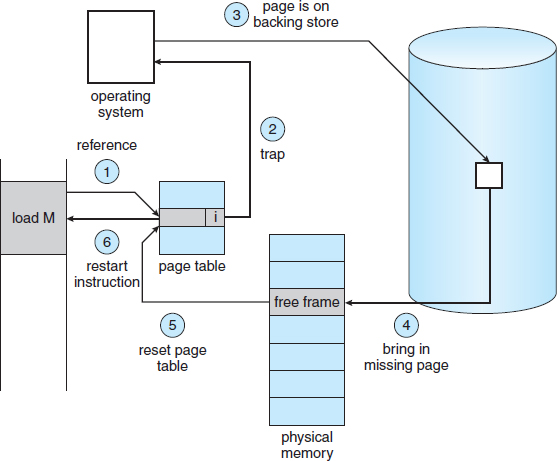

But what happens if the process tries to access a page that was not brought into memory? Access to a page marked invalid causes a page fault. The paging hardware, in translating the address through the page table, will notice that the invalid bit is set, causing a trap to the operating system. This trap is the result of the operating system's failure to bring the desired page into memory. The procedure for handling this page fault is straightforward (Figure 9.6):

- We check an internal table (usually kept with the process control block) for this process to determine whether the reference was a valid or an invalid memory access.

- If the reference was invalid, we terminate the process. If it was valid but we have not yet brought in that page, we now page it in.

- We find a free frame (by taking one from the free-frame list, for example).

- We schedule a disk operation to read the desired page into the newly allocated frame.

- When the disk read is complete, we modify the internal table kept with the process and the page table to indicate that the page is now in memory.

- We restart the instruction that was interrupted by the trap. The process can now access the page as though it had always been in memory.

In the extreme case, we can start executing a process with no pages in memory. When the operating system sets the instruction pointer to the first instruction of the process, which is on a non-memory-resident page, the process immediately faults for the page. After this page is brought into memory, the process continues to execute, faulting as necessary until every page that it needs is in memory. At that point, it can execute with no more faults. This scheme is pure demand paging: never bring a page into memory until it is required.

Theoretically, some programs could access several new pages of memory with each instruction execution (one page for the instruction and many for data), possibly causing multiple page faults per instruction. This situation would result in unacceptable system performance. Fortunately, analysis of running processes shows that this behavior is exceedingly unlikely. Programs tend to have locality of reference, described in Section 9.6.1, which results in reasonable performance from demand paging.

The hardware to support demand paging is the same as the hardware for paging and swapping:

- Page table. This table has the ability to mark an entry invalid through a valid–invalid bit or a special value of protection bits.

- Secondary memory. This memory holds those pages that are not present in main memory. The secondary memory is usually a high-speed disk. It is known as the swap device, and the section of disk used for this purpose is known as swap space. Swap-space allocation is discussed in Chapter 10.

A crucial requirement for demand paging is the ability to restart any instruction after a page fault. Because we save the state (registers, condition code, instruction counter) of the interrupted process when the page fault occurs, we must be able to restart the process in exactly the same place and state, except that the desired page is now in memory and is accessible. In most cases, this requirement is easy to meet. A page fault may occur at any memory reference. If the page fault occurs on the instruction fetch, we can restart by fetching the instruction again. If a page fault occurs while we are fetching an operand, we must fetch and decode the instruction again and then fetch the operand.

As a worst-case example, consider a three-address instruction such as ADD the content of A to B, placing the result in C. These are the steps to execute this instruction:

- Fetch and decode the instruction (ADD).

- Fetch A.

- Fetch B.

- Add A and B.

- Store the sum in C.

If we fault when we try to store in C (because C is in a page not currently in memory), we will have to get the desired page, bring it in, correct the page table, and restart the instruction. The restart will require fetching the instruction again, decoding it again, fetching the two operands again, and then adding again. However, there is not much repeated work (less than one complete instruction), and the repetition is necessary only when a page fault occurs.

The major difficulty arises when one instruction may modify several different locations. For example, consider the IBM System 360/370 MVC (move character) instruction, which can move up to 256 bytes from one location to another (possibly overlapping) location. If either block (source or destination) straddles a page boundary, a page fault might occur after the move is partially done. In addition, if the source and destination blocks overlap, the source block may have been modified, in which case we cannot simply restart the instruction.

This problem can be solved in two different ways. In one solution, the microcode computes and attempts to access both ends of both blocks. If a page fault is going to occur, it will happen at this step, before anything is modified. The move can then take place; we know that no page fault can occur, since all the relevant pages are in memory. The other solution uses temporary registers to hold the values of overwritten locations. If there is a page fault, all the old values are written back into memory before the trap occurs. This action restores memory to its state before the instruction was started, so that the instruction can be repeated.

This is by no means the only architectural problem resulting from adding paging to an existing architecture to allow demand paging, but it illustrates some of the difficulties involved. Paging is added between the CPU and the memory in a computer system. It should be entirely transparent to the user process. Thus, people often assume that paging can be added to any system. Although this assumption is true for a non-demand-paging environment, where a page fault represents a fatal error, it is not true where a page fault means only that an additional page must be brought into memory and the process restarted.

9.2.2 Performance of Demand Paging

Demand paging can significantly affect the performance of a computer system. To see why, let's compute the effective access time for a demand-paged memory. For most computer systems, the memory-access time, denoted ma, ranges from 10 to 200 nanoseconds. As long as we have no page faults, the effective access time is equal to the memory access time. If, however, a page fault occurs, we must first read the relevant page from disk and then access the desired word.

Let p be the probability of a page fault (0 ≤ p ≤ 1). We would expect p to be close to zero—that is, we would expect to have only a few page faults. The effective access time is then

effective access time = (1 − p) × ma + p × page fault time.

To compute the effective access time, we must know how much time is needed to service a page fault. A page fault causes the following sequence to occur:

- Trap to the operating system.

- Save the user registers and process state.

- Determine that the interrupt was a page fault.

- Check that the page reference was legal and determine the location of the page on the disk.

- Issue a read from the disk to a free frame:

- Wait in a queue for this device until the read request is serviced.

- Wait for the device seek and/or latency time.

- Begin the transfer of the page to a free frame.

- While waiting, allocate the CPU to some other user (CPU scheduling, optional).

- Receive an interrupt from the disk I/O subsystem (I/O completed).

- Save the registers and process state for the other user (if step 6 is executed).

- Determine that the interrupt was from the disk.

- Correct the page table and other tables to show that the desired page is now in memory.

- Wait for the CPU to be allocated to this process again.

- Restore the user registers, process state, and new page table, and then resume the interrupted instruction.

Not all of these steps are necessary in every case. For example, we are assuming that, in step 6, the CPU is allocated to another process while the I/O occurs. This arrangement allows multiprogramming to maintain CPU utilization but requires additional time to resume the page-fault service routine when the I/O transfer is complete.

In any case, we are faced with three major components of the page-fault service time:

- Service the page-fault interrupt.

- Read in the page.

- Restart the process.

The first and third tasks can be reduced, with careful coding, to several hundred instructions. These tasks may take from 1 to 100 microseconds each. The page-switch time, however, will probably be close to 8 milliseconds. (A typical hard disk has an average latency of 3 milliseconds, a seek of 5 milliseconds, and a transfer time of 0.05 milliseconds. Thus, the total paging time is about 8 milliseconds, including hardware and software time.) Remember also that we are looking at only the device-service time. If a queue of processes is waiting for the device, we have to add device-queueing time as we wait for the paging device to be free to service our request, increasing even more the time to swap.

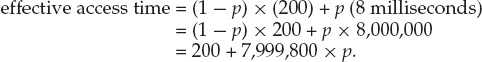

With an average page-fault service time of 8 milliseconds and a memory-access time of 200 nanoseconds, the effective access time in nanoseconds is

We see, then, that the effective access time is directly proportional to the page-fault rate. If one access out of 1,000 causes a page fault, the effective access time is 8.2 microseconds. The computer will be slowed down by a factor of 40 because of demand paging! If we want performance degradation to be less than 10 percent, we need to keep the probability of page faults at the following level:

That is, to keep the slowdown due to paging at a reasonable level, we can allow fewer than one memory access out of 399,990 to page-fault. In sum, it is important to keep the page-fault rate low in a demand-paging system. Otherwise, the effective access time increases, slowing process execution dramatically.

An additional aspect of demand paging is the handling and overall use of swap space. Disk I/O to swap space is generally faster than that to the file system. It is a faster file system because swap space is allocated in much larger blocks, and file lookups and indirect allocation methods are not used (Chapter 10). The system can therefore gain better paging throughput by copying an entire file image into the swap space at process startup and then performing demand paging from the swap space. Another option is to demand pages from the file system initially but to write the pages to swap space as they are replaced. This approach will ensure that only needed pages are read from the file system but that all subsequent paging is done from swap space.

Some systems attempt to limit the amount of swap space used through demand paging of binary files. Demand pages for such files are brought directly from the file system. However, when page replacement is called for, these frames can simply be overwritten (because they are never modified), and the pages can be read in from the file system again if needed. Using this approach, the file system itself serves as the backing store. However, swap space must still be used for pages not associated with a file (known as anonymous memory); these pages include the stack and heap for a process. This method appears to be a good compromise and is used in several systems, including Solaris and BSD UNIX.

Mobile operating systems typically do not support swapping. Instead, these systems demand-page from the file system and reclaim read-only pages (such as code) from applications if memory becomes constrained. Such data can be demand-paged from the file system if it is later needed. Under iOS, anonymous memory pages are never reclaimed from an application unless the application is terminated or explicitly releases the memory.

9.3 Copy-on-Write

In Section 9.2, we illustrated how a process can start quickly by demand-paging in the page containing the first instruction. However, process creation using the fork() system call may initially bypass the need for demand paging by using a technique similar to page sharing (covered in Section 8.5.4). This technique provides rapid process creation and minimizes the number of new pages that must be allocated to the newly created process.

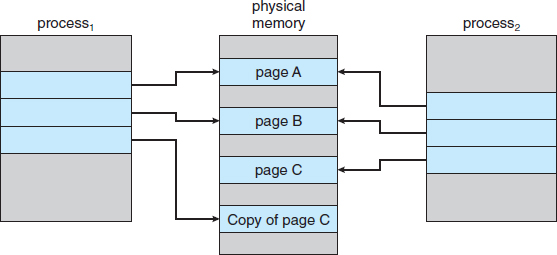

Recall that the fork() system call creates a child process that is a duplicate of its parent. Traditionally, fork() worked by creating a copy of the parent's address space for the child, duplicating the pages belonging to the parent. However, considering that many child processes invoke the exec() system call immediately after creation, the copying of the parent's address space may be unnecessary. Instead, we can use a technique known as copy-on-write, which works by allowing the parent and child processes initially to share the same pages. These shared pages are marked as copy-on-write pages, meaning that if either process writes to a shared page, a copy of the shared page is created. Copy-on-write is illustrated in Figures 9.7 and 9.8, which show the contents of the physical memory before and after process 1 modifies page C.

For example, assume that the child process attempts to modify a page containing portions of the stack, with the pages set to be copy-on-write. The operating system will create a copy of this page, mapping it to the address space of the child process. The child process will then modify its copied page and not the page belonging to the parent process. Obviously, when the copy-on-write technique is used, only the pages that are modified by either process are copied; all unmodified pages can be shared by the parent and child processes. Note, too, that only pages that can be modified need be marked as copy-on-write. Pages that cannot be modified (pages containing executable code) can be shared by the parent and child. Copy-on-write is a common technique used by several operating systems, including Windows XP, Linux, and Solaris.

When it is determined that a page is going to be duplicated using copy-on-write, it is important to note the location from which the free page will be allocated. Many operating systems provide a pool of free pages for such requests. These free pages are typically allocated when the stack or heap for a process must expand or when there are copy-on-write pages to be managed.

Figure 9.7 Before process 1 modifies page C.

Figure 9.8 After process 1 modifies page C.

Operating systems typically allocate these pages using a technique known as zero-fill-on-demand. Zero-fill-on-demand pages have been zeroed-out before being allocated, thus erasing the previous contents.

Several versions of UNIX (including Solaris and Linux) provide a variation of the fork() system call—vfork() (for virtual memory fork)—that operates differently from fork() with copy-on-write. With vfork(), the parent process is suspended, and the child process uses the address space of the parent. Because vfork() does not use copy-on-write, if the child process changes any pages of the parent's address space, the altered pages will be visible to the parent once it resumes. Therefore, vfork() must be used with caution to ensure that the child process does not modify the address space of the parent. vfork() is intended to be used when the child process calls exec() immediately after creation. Because no copying of pages takes place, vfork() is an extremely efficient method of process creation and is sometimes used to implement UNIX command-line shell interfaces.

9.4 Page Replacement

In our earlier discussion of the page-fault rate, we assumed that each page faults at most once, when it is first referenced. This representation is not strictly accurate, however. If a process of ten pages actually uses only half of them, then demand paging saves the I/O necessary to load the five pages that are never used. We could also increase our degree of multiprogramming by running twice as many processes. Thus, if we had forty frames, we could run eight processes, rather than the four that could run if each required ten frames (five of which were never used).

If we increase our degree of multiprogramming, we are over-allocating memory. If we run six processes, each of which is ten pages in size but actually uses only five pages, we have higher CPU utilization and throughput, with ten frames to spare. It is possible, however, that each of these processes, for a particular data set, may suddenly try to use all ten of its pages, resulting in a need for sixty frames when only forty are available.

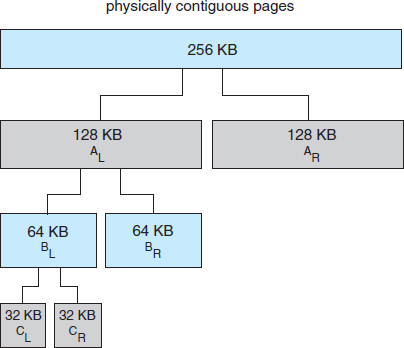

Further, consider that system memory is not used only for holding program pages. Buffers for I/O also consume a considerable amount of memory. This use can increase the strain on memory-placement algorithms. Deciding how much memory to allocate to I/O and how much to program pages is a significant challenge. Some systems allocate a fixed percentage of memory for I/O buffers, whereas others allow both user processes and the I/O subsystem to compete for all system memory.

Figure 9.9 Need for page replacement.

Over-allocation of memory manifests itself as follows. While a user process is executing, a page fault occurs. The operating system determines where the desired page is residing on the disk but then finds that there are no free frames on the free-frame list; all memory is in use (Figure 9.9).

The operating system has several options at this point. It could terminate the user process. However, demand paging is the operating system's attempt to improve the computer system's utilization and throughput. Users should not be aware that their processes are running on a paged system—paging should be logically transparent to the user. So this option is not the best choice.

The operating system could instead swap out a process, freeing all its frames and reducing the level of multiprogramming. This option is a good one in certain circumstances, and we consider it further in Section 9.6. Here, we discuss the most common solution: page replacement.

9.4.1 Basic Page Replacement

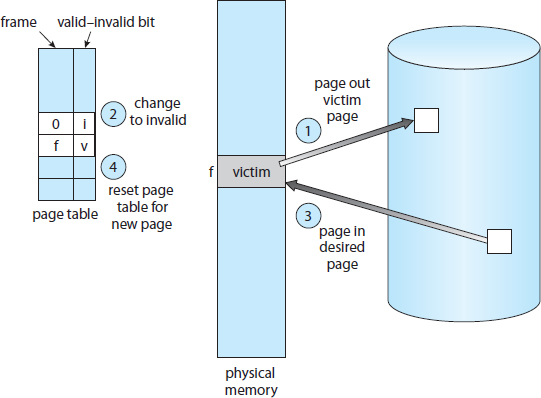

Page replacement takes the following approach. If no frame is free, we find one that is not currently being used and free it. We can free a frame by writing its contents to swap space and changing the page table (and all other tables) to indicate that the page is no longer in memory (Figure 9.10). We can now use the freed frame to hold the page for which the process faulted. We modify the page-fault service routine to include page replacement:

- Find the location of the desired page on the disk.

- Find a free frame:

- If there is a free frame, use it.

- If there is no free frame, use a page-replacement algorithm to select a victim frame.

- Write the victim frame to the disk; change the page and frame tables accordingly.

- Read the desired page into the newly freed frame; change the page and frame tables.

- Continue the user process from where the page fault occurred.

Notice that, if no frames are free, two page transfers (one out and one in) are required. This situation effectively doubles the page-fault service time and increases the effective access time accordingly.

We can reduce this overhead by using a modify bit (or dirty bit). When this scheme is used, each page or frame has a modify bit associated with it in the hardware. The modify bit for a page is set by the hardware whenever any byte in the page is written into, indicating that the page has been modified. When we select a page for replacement, we examine its modify bit. If the bit is set, we know that the page has been modified since it was read in from the disk. In this case, we must write the page to the disk. If the modify bit is not set, however, the page has not been modified since it was read into memory. In this case, we need not write the memory page to the disk: it is already there. This technique also applies to read-only pages (for example, pages of binary code). Such pages cannot be modified; thus, they may be discarded when desired. This scheme can significantly reduce the time required to service a page fault, since it reduces I/O time by one-half if the page has not been modified.

Page replacement is basic to demand paging. It completes the separation between logical memory and physical memory. With this mechanism, an enormous virtual memory can be provided for programmers on a smaller physical memory. With no demand paging, user addresses are mapped into physical addresses, and the two sets of addresses can be different. All the pages of a process still must be in physical memory, however. With demand paging, the size of the logical address space is no longer constrained by physical memory. If we have a user process of twenty pages, we can execute it in ten frames simply by using demand paging and using a replacement algorithm to find a free frame whenever necessary. If a page that has been modified is to be replaced, its contents are copied to the disk. A later reference to that page will cause a page fault. At that time, the page will be brought back into memory, perhaps replacing some other page in the process.

We must solve two major problems to implement demand paging: we must develop a frame-allocation algorithm and a page-replacement algorithm. That is, if we have multiple processes in memory, we must decide how many frames to allocate to each process; and when page replacement is required, we must select the frames that are to be replaced. Designing appropriate algorithms to solve these problems is an important task, because disk I/O is so expensive. Even slight improvements in demand-paging methods yield large gains in system performance.

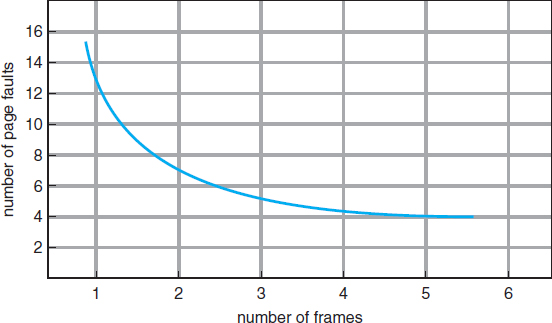

There are many different page-replacement algorithms. Every operating system probably has its own replacement scheme. How do we select a particular replacement algorithm? In general, we want the one with the lowest page-fault rate.

We evaluate an algorithm by running it on a particular string of memory references and computing the number of page faults. The string of memory references is called a reference string. We can generate reference strings artificially (by using a random-number generator, for example), or we can trace a given system and record the address of each memory reference. The latter choice produces a large number of data (on the order of 1 million addresses per second). To reduce the number of data, we use two facts.

First, for a given page size (and the page size is generally fixed by the hardware or system), we need to consider only the page number, rather than the entire address. Second, if we have a reference to a page p, then any references to page p that immediately follow will never cause a page fault. Page p will be in memory after the first reference, so the immediately following references will not fault.

For example, if we trace a particular process, we might record the following address sequence:

0100, 0432, 0101, 0612, 0102, 0103, 0104, 0101, 0611, 0102, 0103,

0104, 0101, 0610, 0102, 0103, 0104, 0101, 0609, 0102, 0105

At 100 bytes per page, this sequence is reduced to the following reference string:

1, 4, 1, 6, 1, 6, 1, 6, 1, 6, 1

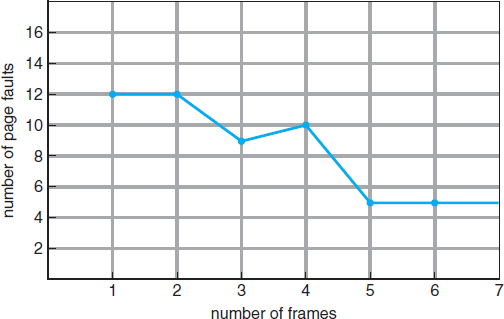

Figure 9.11 Graph of page faults versus number of frames.

To determine the number of page faults for a particular reference string and page-replacement algorithm, we also need to know the number of page frames available. Obviously, as the number of frames available increases, the number of page faults decreases. For the reference string considered previously, for example, if we had three or more frames, we would have only three faults—one fault for the first reference to each page. In contrast, with only one frame available, we would have a replacement with every reference, resulting in eleven faults. In general, we expect a curve such as that in Figure 9.11. As the number of frames increases, the number of page faults drops to some minimal level. Of course, adding physical memory increases the number of frames.

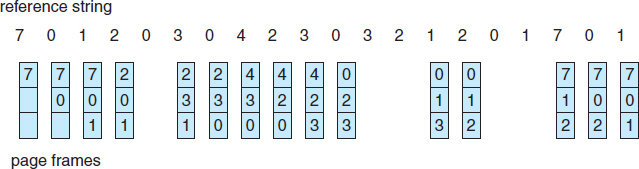

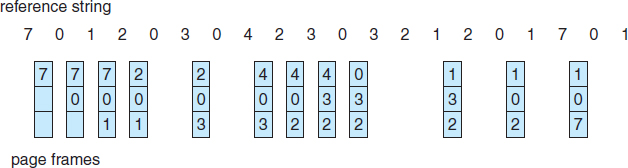

We next illustrate several page-replacement algorithms. In doing so, we use the reference string

7, 0, 1, 2, 0, 3, 0, 4, 2, 3, 0, 3, 2, 1, 2, 0, 1, 7, 0, 1

for a memory with three frames.

9.4.2 FIFO Page Replacement

The simplest page-replacement algorithm is a first-in, first-out (FIFO) algorithm. A FIFO replacement algorithm associates with each page the time when that page was brought into memory. When a page must be replaced, the oldest page is chosen. Notice that it is not strictly necessary to record the time when a page is brought in. We can create a FIFO queue to hold all pages in memory. We replace the page at the head of the queue. When a page is brought into memory, we insert it at the tail of the queue.

For our example reference string, our three frames are initially empty. The first three references (7,0,1) cause page faults and are brought into these empty frames. The next reference (2) replaces page 7, because page 7 was brought in first. Since 0 is the next reference and 0 is already in memory, we have no fault for this reference. The first reference to 3 results in replacement of page 0, since it is now first in line. Because of this replacement, the next reference, to 0, will fault. Page 1 is then replaced by page 0. This process continues as shown in Figure 9.12. Every time a fault occurs, we show which pages are in our three frames. There are fifteen faults altogether.

Figure 9.12 FIFO page-replacement algorithm.

The FIFO page-replacement algorithm is easy to understand and program. However, its performance is not always good. On the one hand, the page replaced may be an initialization module that was used a long time ago and is no longer needed. On the other hand, it could contain a heavily used variable that was initialized early and is in constant use.

Notice that, even if we select for replacement a page that is in active use, everything still works correctly. After we replace an active page with a new one, a fault occurs almost immediately to retrieve the active page. Some other page must be replaced to bring the active page back into memory. Thus, a bad replacement choice increases the page-fault rate and slows process execution. It does not, however, cause incorrect execution.

To illustrate the problems that are possible with a FIFO page-replacement algorithm, consider the following reference string:

1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Figure 9.13 shows the curve of page faults for this reference string versus the number of available frames. Notice that the number of faults for four frames (ten) is greater than the number of faults for three frames (nine)! This most unexpected result is known as Belady's anomaly: for some page-replacement algorithms, the page-fault rate may increase as the number of allocated frames increases. We would expect that giving more memory to a process would improve its performance. In some early research, investigators noticed that this assumption was not always true. Belady's anomaly was discovered as a result.

9.4.3 Optimal Page Replacement

One result of the discovery of Belady's anomaly was the search for an optimal page-replacement algorithm—the algorithm that has the lowest page-fault rate of all algorithms and will never suffer from Belady's anomaly. Such an algorithm does exist and has been called OPT or MIN. It is simply this:

Replace the page that will not be used for the longest period of time.

Use of this page-replacement algorithm guarantees the lowest possible page-fault rate for a fixed number of frames.

Figure 9.13 Page-fault curve for FIFO replacement on a reference string.

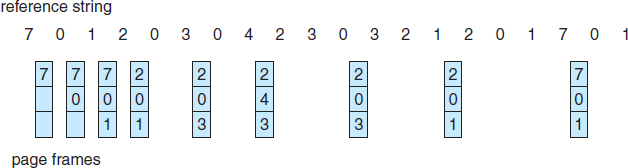

For example, on our sample reference string, the optimal page-replacement algorithm would yield nine page faults, as shown in Figure 9.14. The first three references cause faults that fill the three empty frames. The reference to page 2 replaces page 7, because page 7 will not be used until reference 18, whereas page 0 will be used at 5, and page 1 at 14. The reference to page 3 replaces page 1, as page 1 will be the last of the three pages in memory to be referenced again. With only nine page faults, optimal replacement is much better than a FIFO algorithm, which results in fifteen faults. (If we ignore the first three, which all algorithms must suffer, then optimal replacement is twice as good as FIFO replacement.) In fact, no replacement algorithm can process this reference string in three frames with fewer than nine faults.

Unfortunately, the optimal page-replacement algorithm is difficult to implement, because it requires future knowledge of the reference string. (We encountered a similar situation with the SJF CPU-scheduling algorithm in Section 6.3.2.) As a result, the optimal algorithm is used mainly for comparison studies. For instance, it may be useful to know that, although a new algorithm is not optimal, it is within 12.3 percent of optimal at worst and within 4.7 percent on average.

Figure 9.14 Optimal page-replacement algorithm.

9.4.4 LRU Page Replacement

If the optimal algorithm is not feasible, perhaps an approximation of the optimal algorithm is possible. The key distinction between the FIFO and OPT algorithms (other than looking backward versus forward in time) is that the FIFO algorithm uses the time when a page was brought into memory, whereas the OPT algorithm uses the time when a page is to be used. If we use the recent past as an approximation of the near future, then we can replace the page that has not been used for the longest period of time. This approach is the least recently used (LRU) algorithm.

LRU replacement associates with each page the time of that page's last use. When a page must be replaced, LRU chooses the page that has not been used for the longest period of time. We can think of this strategy as the optimal page-replacement algorithm looking backward in time, rather than forward. (Strangely, if we let SR be the reverse of a reference string S, then the page-fault rate for the OPT algorithm on S is the same as the page-fault rate for the OPT algorithm on SR. Similarly, the page-fault rate for the LRU algorithm on S is the same as the page-fault rate for the LRU algorithm on SR.)

The result of applying LRU replacement to our example reference string is shown in Figure 9.15. The LRU algorithm produces twelve faults. Notice that the first five faults are the same as those for optimal replacement. When the reference to page 4 occurs, however, LRU replacement sees that, of the three frames in memory, page 2 was used least recently. Thus, the LRU algorithm replaces page 2, not knowing that page 2 is about to be used. When it then faults for page 2, the LRU algorithm replaces page 3, since it is now the least recently used of the three pages in memory. Despite these problems, LRU replacement with twelve faults is much better than FIFO replacement with fifteen.

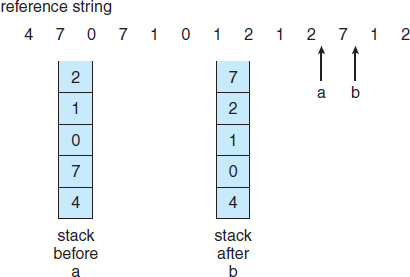

The LRU policy is often used as a page-replacement algorithm and is considered to be good. The major problem is how to implement LRU replacement. An LRU page-replacement algorithm may require substantial hardware assistance. The problem is to determine an order for the frames defined by the time of last use. Two implementations are feasible:

- Counters. In the simplest case, we associate with each page-table entry a time-of-use field and add to the CPU a logical clock or counter. The clock is incremented for every memory reference. Whenever a reference to a page is made, the contents of the clock register are copied to the time-of-use field in the page-table entry for that page. In this way, we always have the “time” of the last reference to each page. We replace the page with the smallest time value. This scheme requires a search of the page table to find the LRU page and a write to memory (to the time-of-use field in the page table) for each memory access. The times must also be maintained when page tables are changed (due to CPU scheduling). Overflow of the clock must be considered.

- Stack. Another approach to implementing LRU replacement is to keep a stack of page numbers. Whenever a page is referenced, it is removed from the stack and put on the top. In this way, the most recently used page is always at the top of the stack and the least recently used page is always at the bottom (Figure 9.16). Because entries must be removed from the middle of the stack, it is best to implement this approach by using a doubly linked list with a head pointer and a tail pointer. Removing a page and putting it on the top of the stack then requires changing six pointers at worst. Each update is a little more expensive, but there is no search for a replacement; the tail pointer points to the bottom of the stack, which is the LRU page. This approach is particularly appropriate for software or microcode implementations of LRU replacement.

Like optimal replacement, LRU replacement does not suffer from Belady's anomaly. Both belong to a class of page-replacement algorithms, called stack algorithms, that can never exhibit Belady's anomaly. A stack algorithm is an algorithm for which it can be shown that the set of pages in memory for n frames is always a subset of the set of pages that would be in memory with n + 1 frames. For LRU replacement, the set of pages in memory would be the n most recently referenced pages. If the number of frames is increased, these n pages will still be the most recently referenced and so will still be in memory.

Note that neither implementation of LRU would be conceivable without hardware assistance beyond the standard TLB registers. The updating of the clock fields or stack must be done for every memory reference. If we were to use an interrupt for every reference to allow software to update such data structures, it would slow every memory reference by a factor of at least ten, hence slowing every user process by a factor of ten. Few systems could tolerate that level of overhead for memory management.

Figure 9.16 Use of a stack to record the most recent page references.

9.4.5 LRU-Approximation Page Replacement

Few computer systems provide sufficient hardware support for true LRU page replacement. In fact, some systems provide no hardware support, and other page-replacement algorithms (such as a FIFO algorithm) must be used. Many systems provide some help, however, in the form of a reference bit. The reference bit for a page is set by the hardware whenever that page is referenced (either a read or a write to any byte in the page). Reference bits are associated with each entry in the page table.

Initially, all bits are cleared (to 0) by the operating system. As a user process executes, the bit associated with each page referenced is set (to 1) by the hardware. After some time, we can determine which pages have been used and which have not been used by examining the reference bits, although we do not know the order of use. This information is the basis for many page-replacement algorithms that approximate LRU replacement.

9.4.5.1 Additional-Reference-Bits Algorithm

We can gain additional ordering information by recording the reference bits at regular intervals. We can keep an 8-bit byte for each page in a table in memory. At regular intervals (say, every 100 milliseconds), a timer interrupt transfers control to the operating system. The operating system shifts the reference bit for each page into the high-order bit of its 8-bit byte, shifting the other bits right by 1 bit and discarding the low-order bit. These 8-bit shift registers contain the history of page use for the last eight time periods. If the shift register contains 00000000, for example, then the page has not been used for eight time periods. A page that is used at least once in each period has a shift register value of 11111111. A page with a history register value of 11000100 has been used more recently than one with a value of 01110111. If we interpret these 8-bit bytes as unsigned integers, the page with the lowest number is the LRU page, and it can be replaced. Notice that the numbers are not guaranteed to be unique, however. We can either replace (swap out) all pages with the smallest value or use the FIFO method to choose among them.

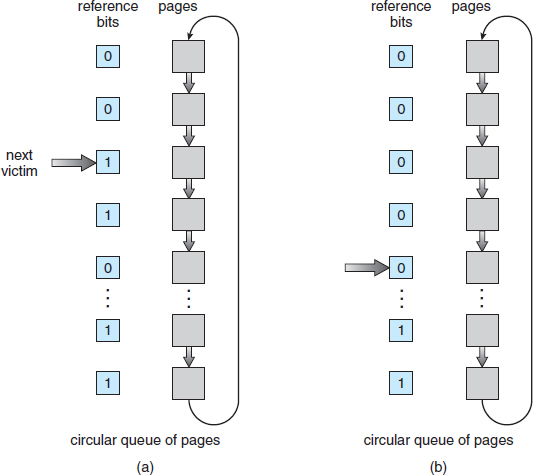

The number of bits of history included in the shift register can be varied, of course, and is selected (depending on the hardware available) to make the updating as fast as possible. In the extreme case, the number can be reduced to zero, leaving only the reference bit itself. This algorithm is called the second-chance page-replacement algorithm.

9.4.5.2 Second-Chance Algorithm

The basic algorithm of second-chance replacement is a FIFO replacement algorithm. When a page has been selected, however, we inspect its reference bit. If the value is 0, we proceed to replace this page; but if the reference bit is set to 1, we give the page a second chance and move on to select the next FIFO page. When a page gets a second chance, its reference bit is cleared, and its arrival time is reset to the current time. Thus, a page that is given a second chance will not be replaced until all other pages have been replaced (or given second chances). In addition, if a page is used often enough to keep its reference bit set, it will never be replaced.

Figure 9.17 Second-chance (clock) page-replacement algorithm.

One way to implement the second-chance algorithm (sometimes referred to as the clock algorithm) is as a circular queue. A pointer (that is, a hand on the clock) indicates which page is to be replaced next. When a frame is needed, the pointer advances until it finds a page with a 0 reference bit. As it advances, it clears the reference bits (Figure 9.17). Once a victim page is found, the page is replaced, and the new page is inserted in the circular queue in that position. Notice that, in the worst case, when all bits are set, the pointer cycles through the whole queue, giving each page a second chance. It clears all the reference bits before selecting the next page for replacement. Second-chance replacement degenerates to FIFO replacement if all bits are set.

9.4.5.3 Enhanced Second-Chance Algorithm

We can enhance the second-chance algorithm by considering the reference bit and the modify bit (described in Section 9.4.1) as an ordered pair. With these two bits, we have the following four possible classes:

- (0, 0) neither recently used nor modified—best page to replace

- (0, 1) not recently used but modified—not quite as good, because the page will need to be written out before replacement

- (1, 0) recently used but clean—probably will be used again soon

- (1, 1) recently used and modified—probably will be used again soon, and the page will be need to be written out to disk before it can be replaced

Each page is in one of these four classes. When page replacement is called for, we use the same scheme as in the clock algorithm; but instead of examining whether the page to which we are pointing has the reference bit set to 1, we examine the class to which that page belongs. We replace the first page encountered in the lowest nonempty class. Notice that we may have to scan the circular queue several times before we find a page to be replaced.

The major difference between this algorithm and the simpler clock algorithm is that here we give preference to those pages that have been modified in order to reduce the number of I/Os required.

9.4.6 Counting-Based Page Replacement

There are many other algorithms that can be used for page replacement. For example, we can keep a counter of the number of references that have been made to each page and develop the following two schemes.

- The least frequently used (LFU) page-replacement algorithm requires that the page with the smallest count be replaced. The reason for this selection is that an actively used page should have a large reference count. A problem arises, however, when a page is used heavily during the initial phase of a process but then is never used again. Since it was used heavily, it has a large count and remains in memory even though it is no longer needed. One solution is to shift the counts right by 1 bit at regular intervals, forming an exponentially decaying average usage count.

- The most frequently used (MFU) page-replacement algorithm is based on the argument that the page with the smallest count was probably just brought in and has yet to be used.

As you might expect, neither MFU nor LFU replacement is common. The implementation of these algorithms is expensive, and they do not approximate OPT replacement well.

9.4.7 Page-Buffering Algorithms

Other procedures are often used in addition to a specific page-replacement algorithm. For example, systems commonly keep a pool of free frames. When a page fault occurs, a victim frame is chosen as before. However, the desired page is read into a free frame from the pool before the victim is written out. This procedure allows the process to restart as soon as possible, without waiting for the victim page to be written out. When the victim is later written out, its frame is added to the free-frame pool.

An expansion of this idea is to maintain a list of modified pages. Whenever the paging device is idle, a modified page is selected and is written to the disk. Its modify bit is then reset. This scheme increases the probability that a page will be clean when it is selected for replacement and will not need to be written out.

Another modification is to keep a pool of free frames but to remember which page was in each frame. Since the frame contents are not modified when a frame is written to the disk, the old page can be reused directly from the free-frame pool if it is needed before that frame is reused. No I/O is needed in this case. When a page fault occurs, we first check whether the desired page is in the free-frame pool. If it is not, we must select a free frame and read into it.

This technique is used in the VAX/VMS system along with a FIFO replacement algorithm. When the FIFO replacement algorithm mistakenly replaces a page that is still in active use, that page is quickly retrieved from the free-frame pool, and no I/O is necessary. The free-frame buffer provides protection against the relatively poor, but simple, FIFO replacement algorithm. This method is necessary because the early versions of VAX did not implement the reference bit correctly.

Some versions of the UNIX system use this method in conjunction with the second-chance algorithm. It can be a useful augmentation to any page replacement algorithm, to reduce the penalty incurred if the wrong victim page is selected.

9.4.8 Applications and Page Replacement

In certain cases, applications accessing data through the operating system's virtual memory perform worse than if the operating system provided no buffering at all. A typical example is a database, which provides its own memory management and I/O buffering. Applications like this understand their memory use and disk use better than does an operating system that is implementing algorithms for general-purpose use. If the operating system is buffering I/O and the application is doing so as well, however, then twice the memory is being used for a set of I/O.

In another example, data warehouses frequently perform massive sequential disk reads, followed by computations and writes. The LRU algorithm would be removing old pages and preserving new ones, while the application would more likely be reading older pages than newer ones (as it starts its sequential reads again). Here, MFU would actually be more efficient than LRU.

Because of such problems, some operating systems give special programs the ability to use a disk partition as a large sequential array of logical blocks, without any file-system data structures. This array is sometimes called the raw disk, and I/O to this array is termed raw I/O. Raw I/O bypasses all the file-system services, such as file I/O demand paging, file locking, prefetching, space allocation, file names, and directories. Note that although certain applications are more efficient when implementing their own special-purpose storage services on a raw partition, most applications perform better when they use the regular file-system services.

9.5 Allocation of Frames

We turn next to the issue of allocation. How do we allocate the fixed amount of free memory among the various processes? If we have 93 free frames and two processes, how many frames does each process get?

The simplest case is the single-user system. Consider a single-user system with 128 KB of memory composed of pages 1 KB in size. This system has 128 frames. The operating system may take 35 KB, leaving 93 frames for the user process. Under pure demand paging, all 93 frames would initially be put on the free-frame list. When a user process started execution, it would generate a sequence of page faults. The first 93 page faults would all get free frames from the free-frame list. When the free-frame list was exhausted, a page-replacement algorithm would be used to select one of the 93 in-memory pages to be replaced with the 94th, and so on. When the process terminated, the 93 frames would once again be placed on the free-frame list.

There are many variations on this simple strategy. We can require that the operating system allocate all its buffer and table space from the free-frame list. When this space is not in use by the operating system, it can be used to support user paging. We can try to keep three free frames reserved on the free-frame list at all times. Thus, when a page fault occurs, there is a free frame available to page into. While the page swap is taking place, a replacement can be selected, which is then written to the disk as the user process continues to execute. Other variants are also possible, but the basic strategy is clear: the user process is allocated any free frame.

9.5.1 Minimum Number of Frames

Our strategies for the allocation of frames are constrained in various ways. We cannot, for example, allocate more than the total number of available frames (unless there is page sharing). We must also allocate at least a minimum number of frames. Here, we look more closely at the latter requirement.

One reason for allocating at least a minimum number of frames involves performance. Obviously, as the number of frames allocated to each process decreases, the page-fault rate increases, slowing process execution. In addition, remember that, when a page fault occurs before an executing instruction is complete, the instruction must be restarted. Consequently, we must have enough frames to hold all the different pages that any single instruction can reference.

For example, consider a machine in which all memory-reference instructions may reference only one memory address. In this case, we need at least one frame for the instruction and one frame for the memory reference. In addition, if one-level indirect addressing is allowed (for example, a load instruction on page 16 can refer to an address on page 0, which is an indirect reference to page 23), then paging requires at least three frames per process. Think about what might happen if a process had only two frames.

The minimum number of frames is defined by the computer architecture. For example, the move instruction for the PDP-11 includes more than one word for some addressing modes, and thus the instruction itself may straddle two pages. In addition, each of its two operands may be indirect references, for a total of six frames. Another example is the IBM 370 MVC instruction. Since the instruction is from storage location to storage location, it takes 6 bytes and can straddle two pages. The block of characters to move and the area to which it is to be moved can each also straddle two pages. This situation would require six frames. The worst case occurs when the MVC instruction is the operand of an EXECUTE instruction that straddles a page boundary; in this case, we need eight frames.

The worst-case scenario occurs in computer architectures that allow multiple levels of indirection (for example, each 16-bit word could contain a 15-bit address plus a 1-bit indirect indicator). Theoretically, a simple load instruction could reference an indirect address that could reference an indirect address (on another page) that could also reference an indirect address (on yet another page), and so on, until every page in virtual memory had been touched. Thus, in the worst case, the entire virtual memory must be in physical memory. To overcome this difficulty, we must place a limit on the levels of indirection (for example, limit an instruction to at most 16 levels of indirection). When the first indirection occurs, a counter is set to 16; the counter is then decremented for each successive indirection for this instruction. If the counter is decremented to 0, a trap occurs (excessive indirection). This limitation reduces the maximum number of memory references per instruction to 17, requiring the same number of frames.

Whereas the minimum number of frames per process is defined by the architecture, the maximum number is defined by the amount of available physical memory. In between, we are still left with significant choice in frame allocation.

9.5.2 Allocation Algorithms

The easiest way to split m frames among n processes is to give everyone an equal share, m/n frames (ignoring frames needed by the operating system for the moment). For instance, if there are 93 frames and five processes, each process will get 18 frames. The three leftover frames can be used as a free-frame buffer pool. This scheme is called equal allocation.

An alternative is to recognize that various processes will need differing amounts of memory. Consider a system with a 1-KB frame size. If a small student process of 10 KB and an interactive database of 127 KB are the only two processes running in a system with 62 free frames, it does not make much sense to give each process 31 frames. The student process does not need more than 10 frames, so the other 21 are, strictly speaking, wasted.

To solve this problem, we can use proportional allocation, in which we allocate available memory to each process according to its size. Let the size of the virtual memory for process pi be si, and define

![]()

Then, if the total number of available frames is m, we allocate ai frames to process pi, where ai is approximately

![]()

Of course, we must adjust each ai to be an integer that is greater than the minimum number of frames required by the instruction set, with a sum not exceeding m.

With proportional allocation, we would split 62 frames between two processes, one of 10 pages and one of 127 pages, by allocating 4 frames and 57 frames, respectively, since

![]()

In this way, both processes share the available frames according to their “needs,” rather than equally.

In both equal and proportional allocation, of course, the allocation may vary according to the multiprogramming level. If the multiprogramming level is increased, each process will lose some frames to provide the memory needed for the new process. Conversely, if the multiprogramming level decreases, the frames that were allocated to the departed process can be spread over the remaining processes.

Notice that, with either equal or proportional allocation, a high-priority process is treated the same as a low-priority process. By its definition, however, we may want to give the high-priority process more memory to speed its execution, to the detriment of low-priority processes. One solution is to use a proportional allocation scheme wherein the ratio of frames depends not on the relative sizes of processes but rather on the priorities of processes or on a combination of size and priority.

9.5.3 Global versus Local Allocation

Another important factor in the way frames are allocated to the various processes is page replacement. With multiple processes competing for frames, we can classify page-replacement algorithms into two broad categories: global replacement and local replacement. Global replacement allows a process to select a replacement frame from the set of all frames, even if that frame is currently allocated to some other process; that is, one process can take a frame from another. Local replacement requires that each process select from only its own set of allocated frames.

For example, consider an allocation scheme wherein we allow high-priority processes to select frames from low-priority processes for replacement. A process can select a replacement from among its own frames or the frames of any lower-priority process. This approach allows a high-priority process to increase its frame allocation at the expense of a low-priority process. With a local replacement strategy, the number of frames allocated to a process does not change. With global replacement, a process may happen to select only frames allocated to other processes, thus increasing the number of frames allocated to it (assuming that other processes do not choose its frames for replacement).

One problem with a global replacement algorithm is that a process cannot control its own page-fault rate. The set of pages in memory for a process depends not only on the paging behavior of that process but also on the paging behavior of other processes. Therefore, the same process may perform quite differently (for example, taking 0.5 seconds for one execution and 10.3 seconds for the next execution) because of totally external circumstances. Such is not the case with a local replacement algorithm. Under local replacement, the set of pages in memory for a process is affected by the paging behavior of only that process. Local replacement might hinder a process, however, by not making available to it other, less used pages of memory. Thus, global replacement generally results in greater system throughput and is therefore the more commonly used method.

9.5.4 Non-Uniform Memory Access

Thus far in our coverage of virtual memory, we have assumed that all main memory is created equal—or at least that it is accessed equally. On many computer systems, that is not the case. Often, in systems with multiple CPUs (Section 1.3.2), a given CPU can access some sections of main memory faster than it can access others. These performance differences are caused by how CPUs and memory are interconnected in the system. Frequently, such a system is made up of several system boards, each containing multiple CPUs and some memory. The system boards are interconnected in various ways, ranging from system buses to high-speed network connections like InfiniBand. As you might expect, the CPUs on a particular board can access the memory on that board with less delay than they can access memory on other boards in the system. Systems in which memory access times vary significantly are known collectively as non-uniform memory access (NUMA) systems, and without exception, they are slower than systems in which memory and CPUs are located on the same motherboard.

Managing which page frames are stored at which locations can significantly affect performance in NUMA systems. If we treat memory as uniform in such a system, CPUs may wait significantly longer for memory access than if we modify memory allocation algorithms to take NUMA into account. Similar changes must be made to the scheduling system. The goal of these changes is to have memory frames allocated “as close as possible” to the CPU on which the process is running. The definition of “close” is “with minimum latency,” which typically means on the same system board as the CPU.

The algorithmic changes consist of having the scheduler track the last CPU on which each process ran. If the scheduler tries to schedule each process onto its previous CPU, and the memory-management system tries to allocate frames for the process close to the CPU on which it is being scheduled, then improved cache hits and decreased memory access times will result.

The picture is more complicated once threads are added. For example, a process with many running threads may end up with those threads scheduled on many different system boards. How is the memory to be allocated in this case? Solaris solves the problem by creating lgroups (for “latency groups”) in the kernel. Each lgroup gathers together close CPUs and memory. In fact, there is a hierarchy of lgroups based on the amount of latency between the groups. Solaris tries to schedule all threads of a process and allocate all memory of a process within an lgroup. If that is not possible, it picks nearby lgroups for the rest of the resources needed. This practice minimizes overall memory latency and maximizes CPU cache hit rates.

9.6 Thrashing

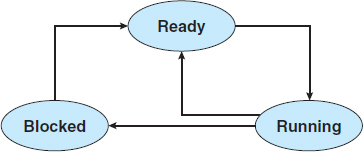

If the number of frames allocated to a low-priority process falls below the minimum number required by the computer architecture, we must suspend that process's execution. We should then page out its remaining pages, freeing all its allocated frames. This provision introduces a swap-in, swap-out level of intermediate CPU scheduling.

In fact, look at any process that does not have “enough” frames. If the process does not have the number of frames it needs to support pages in active use, it will quickly page-fault. At this point, it must replace some page. However, since all its pages are in active use, it must replace a page that will be needed again right away. Consequently, it quickly faults again, and again, and again, replacing pages that it must bring back in immediately.

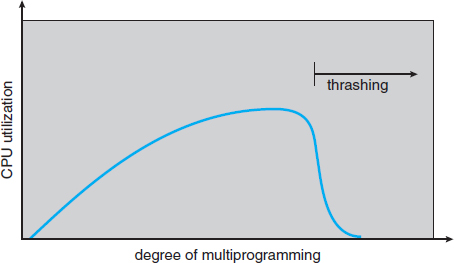

This high paging activity is called thrashing. A process is thrashing if it is spending more time paging than executing.

9.6.1 Cause of Thrashing

Thrashing results in severe performance problems. Consider the following scenario, which is based on the actual behavior of early paging systems.

The operating system monitors CPU utilization. If CPU utilization is too low, we increase the degree of multiprogramming by introducing a new process to the system. A global page-replacement algorithm is used; it replaces pages without regard to the process to which they belong. Now suppose that a process enters a new phase in its execution and needs more frames. It starts faulting and taking frames away from other processes. These processes need those pages, however, and so they also fault, taking frames from other processes. These faulting processes must use the paging device to swap pages in and out. As they queue up for the paging device, the ready queue empties. As processes wait for the paging device, CPU utilization decreases.

The CPU scheduler sees the decreasing CPU utilization and increases the degree of multiprogramming as a result. The new process tries to get started by taking frames from running processes, causing more page faults and a longer queue for the paging device. As a result, CPU utilization drops even further, and the CPU scheduler tries to increase the degree of multiprogramming even more. Thrashing has occurred, and system throughput plunges. The page-fault rate increases tremendously. As a result, the effective memory-access time increases. No work is getting done, because the processes are spending all their time paging.

This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 9.18, in which CPU utilization is plotted against the degree of multiprogramming. As the degree of multiprogramming increases, CPU utilization also increases, although more slowly, until a maximum is reached. If the degree of multiprogramming is increased even further, thrashing sets in, and CPU utilization drops sharply. At this point, to increase CPU utilization and stop thrashing, we must decrease the degree of multiprogramming.

We can limit the effects of thrashing by using a local replacement algorithm (or priority replacement algorithm). With local replacement, if one process starts thrashing, it cannot steal frames from another process and cause the latter to thrash as well. However, the problem is not entirely solved. If processes are thrashing, they will be in the queue for the paging device most of the time. The average service time for a page fault will increase because of the longer average queue for the paging device. Thus, the effective access time will increase even for a process that is not thrashing.

To prevent thrashing, we must provide a process with as many frames as it needs. But how do we know how many frames it “needs”? There are several techniques. The working-set strategy (Section 9.6.2) starts by looking at how many frames a process is actually using. This approach defines the locality model of process execution.

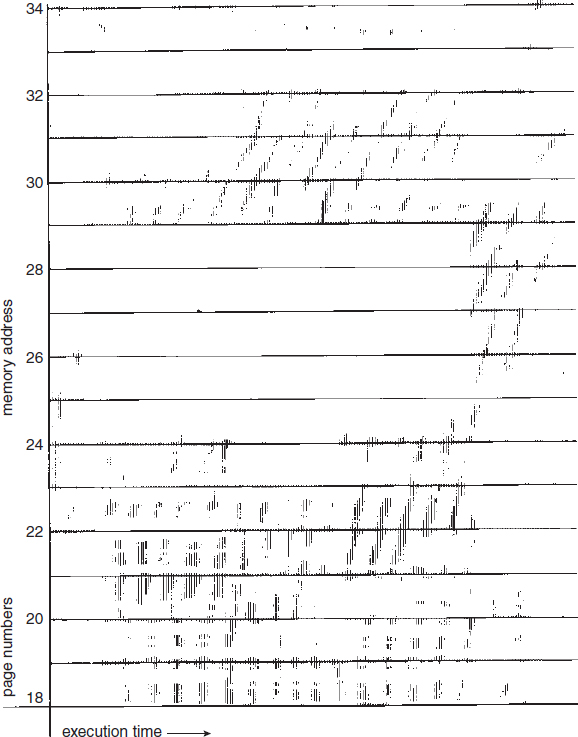

The locality model states that, as a process executes, it moves from locality to locality. A locality is a set of pages that are actively used together (Figure 9.19). A program is generally composed of several different localities, which may overlap.

For example, when a function is called, it defines a new locality. In this locality, memory references are made to the instructions of the function call, its local variables, and a subset of the global variables. When we exit the function, the process leaves this locality, since the local variables and instructions of the function are no longer in active use. We may return to this locality later.

Thus, we see that localities are defined by the program structure and its data structures. The locality model states that all programs will exhibit this basic memory reference structure. Note that the locality model is the unstated principle behind the caching discussions so far in this book. If accesses to any types of data were random rather than patterned, caching would be useless.

Suppose we allocate enough frames to a process to accommodate its current locality. It will fault for the pages in its locality until all these pages are in memory; then, it will not fault again until it changes localities. If we do not allocate enough frames to accommodate the size of the current locality, the process will thrash, since it cannot keep in memory all the pages that it is actively using.

9.6.2 Working-Set Model

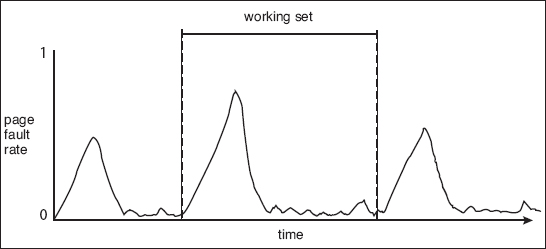

As mentioned, the working-set model is based on the assumption of locality. This model uses a parameter, Δ, to define the working-set window. The idea is to examine the most recent Δ page references. The set of pages in the most recent Δ page references is the working set (Figure 9.20). If a page is in active use, it will be in the working set. If it is no longer being used, it will drop from the working set Δ time units after its last reference. Thus, the working set is an approximation of the program's locality.

For example, given the sequence of memory references shown in Figure 9.20, if Δ = 10 memory references, then the working set at time t1 is {1, 2, 5, 6, 7}. By time t2, the working set has changed to {3, 4}.

The accuracy of the working set depends on the selection of Δ. If Δ is too small, it will not encompass the entire locality; if Δ is too large, it may overlap several localities. In the extreme, if Δ is infinite, the working set is the set of pages touched during the process execution.

Figure 9.19 Locality in a memory-reference pattern.

The most important property of the working set, then, is its size. If we compute the working-set size, WSSi, for each process in the system, we can then consider that

![]()

where D is the total demand for frames. Each process is actively using the pages in its working set. Thus, process i needs WSSi frames. If the total demand is greater than the total number of available frames (D > m), thrashing will occur, because some processes will not have enough frames.

Once Δ has been selected, use of the working-set model is simple. The operating system monitors the working set of each process and allocates to that working set enough frames to provide it with its working-set size. If there are enough extra frames, another process can be initiated. If the sum of the working-set sizes increases, exceeding the total number of available frames, the operating system selects a process to suspend. The process's pages are written out (swapped), and its frames are reallocated to other processes. The suspended process can be restarted later.

Figure 9.20 Working-set model.

This working-set strategy prevents thrashing while keeping the degree of multiprogramming as high as possible. Thus, it optimizes CPU utilization. The difficulty with the working-set model is keeping track of the working set. The working-set window is a moving window. At each memory reference, a new reference appears at one end, and the oldest reference drops off the other end. A page is in the working set if it is referenced anywhere in the working-set window.

We can approximate the working-set model with a fixed-interval timer interrupt and a reference bit. For example, assume that Δ equals 10,000 references and that we can cause a timer interrupt every 5,000 references. When we get a timer interrupt, we copy and clear the reference-bit values for each page. Thus, if a page fault occurs, we can examine the current reference bit and two in-memory bits to determine whether a page was used within the last 10,000 to 15,000 references. If it was used, at least one of these bits will be on. If it has not been used, these bits will be off. Pages with at least one bit on will be considered to be in the working set.

Note that this arrangement is not entirely accurate, because we cannot tell where, within an interval of 5,000, a reference occurred. We can reduce the uncertainty by increasing the number of history bits and the frequency of interrupts (for example, 10 bits and interrupts every 1,000 references). However, the cost to service these more frequent interrupts will be correspondingly higher.

9.6.3 Page-Fault Frequency

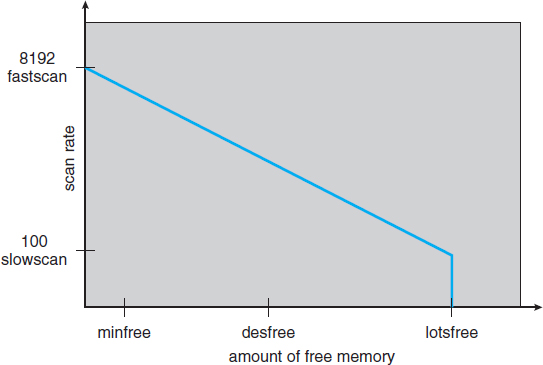

The working-set model is successful, and knowledge of the working set can be useful for prepaging (Section 9.9.1), but it seems a clumsy way to control thrashing. A strategy that uses the page-fault frequency (PFF) takes a more direct approach.

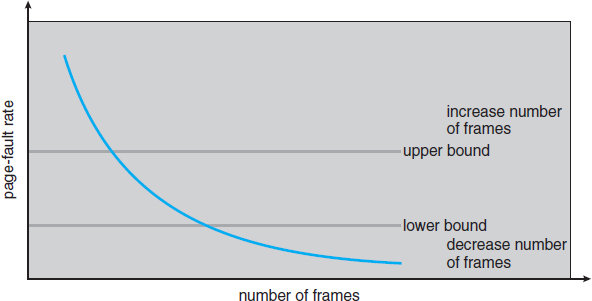

The specific problem is how to prevent thrashing. Thrashing has a high page-fault rate. Thus, we want to control the page-fault rate. When it is too high, we know that the process needs more frames. Conversely, if the page-fault rate is too low, then the process may have too many frames. We can establish upper and lower bounds on the desired page-fault rate (Figure 9.21). If the actual page-fault rate exceeds the upper limit, we allocate the process another frame. If the page-fault rate falls below the lower limit, we remove a frame from the process. Thus, we can directly measure and control the page-fault rate to prevent thrashing.

Figure 9.21 Page-fault frequency.

As with the working-set strategy, we may have to swap out a process. If the page-fault rate increases and no free frames are available, we must select some process and swap it out to backing store. The freed frames are then distributed to processes with high page-fault rates.

9.6.4 Concluding Remarks

Practically speaking, thrashing and the resulting swapping have a disagreeably large impact on performance. The current best practice in implementing a computer facility is to include enough physical memory, whenever possible, to avoid thrashing and swapping. From smartphones through mainframes, providing enough memory to keep all working sets in memory concurrently, except under extreme conditions, gives the best user experience.

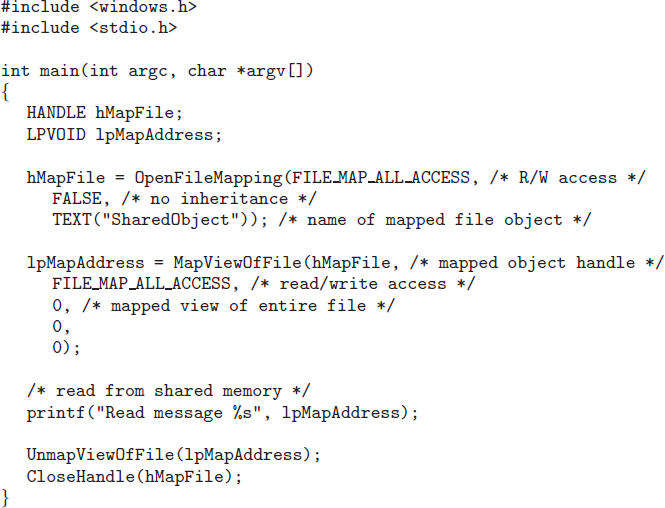

9.7 Memory-Mapped Files

Consider a sequential read of a file on disk using the standard system calls open(), read(), and write(). Each file access requires a system call and disk access. Alternatively, we can use the virtual memory techniques discussed so far to treat file I/O as routine memory accesses. This approach, known as memory mapping a file, allows a part of the virtual address space to be logically associated with the file. As we shall see, this can lead to significant performance increases.

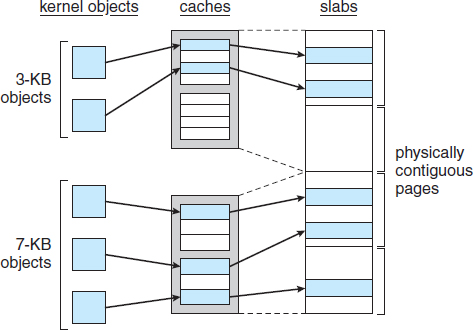

9.7.1 Basic Mechanism

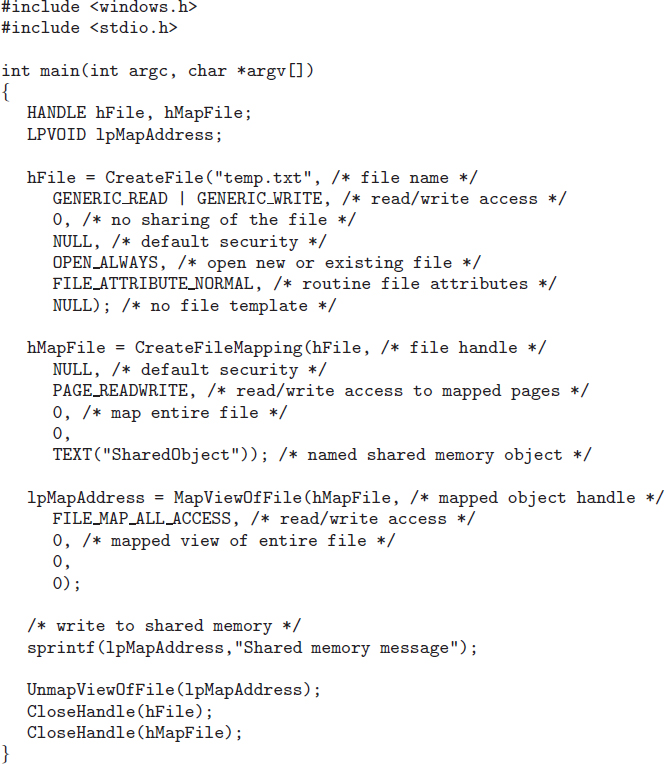

Memory mapping a file is accomplished by mapping a disk block to a page (or pages) in memory. Initial access to the file proceeds through ordinary demand paging, resulting in a page fault. However, a page-sized portion of the file is read from the file system into a physical page (some systems may opt to read in more than a page-sized chunk of memory at a time). Subsequent reads and writes to the file are handled as routine memory accesses. Manipulating files through memory rather than incurring the overhead of using the read() and write() system calls simplifies and speeds up file access and usage.