Key Factors and Trends Affecting Tourism Growth Leading to Overtourism

Introduction

This chapter highlights some of the key factors and trends that have affected tourism growth. Global mass mobility, digitalization, new technology, the 2008 global economic crisis, terrorist attacks, changing behavior, and preferences among travelers have had a profound effect on the global tourism industry over the last two decades. The coronavirus pandemic accelerated technological changes and digitalization as the world adapted to the “new normal.”

Affluence and Aspirational Travel—the Key International Source Markets

Tourism remains an aspirational activity and people will continue to travel as and when they can. The world’s population has also expanded rapidly leading to increased urbanization and population density. Thus, in many ways, the evolution of tourism has just begun. Global mass mobility is here to stay and, although, the way people travel may change due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic it is unlikely to dampen growth in the longer term.

As of the end of August 2020, Euromonitor International estimated that the travel and tourism industry will experience a long-lasting negative economic impact across the entire tourism value chain and that recovery will take between five and ten years depending on the sector (Travel 2040: Sustainability and Digital Transformation as Recovery Drivers 2020). Therefore, destinations should use this time to plan for recovery and regeneration toward a more sustainable tourism model.

Table 4.1 shows that the top ten international source markets were responsible for 46.2 percent of total international tourism expenditure in 2018. It should be noted that with regard to China only a relatively small proportion (around 150 million) of the total population traveled internationally in 2018, which explains why the expenditure per capita is so low. Prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Chinese travelers were forecast to take 160 million trips abroad in 2020, making them the fastest-growing international source market in the world. In contrast Germans took 109 million outbound trips in 2018 indicating that most of the population travels abroad at least once a year. Global tourism receipts have more than tripled since 2000 and currently account for around 7 percent of global exports and services making tourism the fifth largest traded services sector (UNWTO Tourism Dashboard | UNWTO 2020).

Prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Euromonitor International anticipated that the global travel and tourism industry would continue to power on and expected the sector to grow by 3.3 percent year on year in constant terms, forecasting it to top more than £2.3 trillion by 2024. It is estimated that online sales currently account for just over half of all sales (52 percent) with mobile sales representing a quarter of all travel bookings in value terms as the travel industry continues its digital transformation (The Impact of the Coronavirus on the Global Economy | Market Research Report | Euromonitor 2020).

Table 4.1 Top ten international tourism spenders 2018

Top ten international tourism spenders 2018 |

Expenditure USD (billion) |

Population 2020 (million) |

Expenditure per Capita USD |

Market Share % |

China |

277 |

1,438 |

193 |

8.2 |

United States |

144 |

331 |

436 |

7.7 |

Germany |

96 |

84 |

1,142 |

7.0 |

UK |

69 |

68 |

1,016 |

4.9 |

France |

48 |

65 |

734 |

4.0 |

Australia |

37 |

26 |

1,451 |

3.2 |

Korea |

35 |

51 |

684 |

3.2 |

Russia |

34 |

146 |

235 |

2.8 |

Italy |

30 |

61 |

498 |

2.6 |

Spain |

27 |

47 |

573 |

2.6 |

World |

1,398 |

7,775 |

180 |

100 |

Source: UNWTO 2020

The world’s population is becoming increasingly affluent. It is estimated that a billion more people will be in the global middle class by 2030 (Bremner 2019). With travel becoming ever more accessible, the sector is likely to continue to grow at unsustainable levels in the longer term once the global economy recovers from the coronavirus pandemic. The anticipated growth in tourism demand will be driven by rising incomes in emerging markets making travel more accessible to a wider range of audiences, causing an 8 percent annual growth compared to the 4.3 percent growth of international arrivals. The average spend per arrival is expected to hold up to price pressures and will marginally increase to £854 by 2024, up from £844 in 2019, which points to a shift toward higher spending per trip as destinations transition toward a more sustainable tourism model (Bremner 2019).

The coronavirus pandemic forced governments and destinations to take stock and re-evaluate the economic benefits and in many places the necessity of the tourism sector, while at the same time considering the potential of the tourism sector to enhance the quality of life and wellbeing of the local community. Questions have been raised as to whether destinations really wish to go back to business as usual including rapid growth and high volumes of low-value visitors, lack of investment in infrastructure, and little consideration for the local host community and natural environment. According to the Travel Foundation:

this seems unlikely given the risks of future pandemics, geo-political uncertainty, dwindling resources and climate change. While issues of overtourism and unchecked growth may now seem a distant memory, the “weight” of tourism will return, and with it, renewed pressure on destinations struggling to cope or trying to figure out what their own growth trajectory may look like (Sampson 2020).

The task of rebuilding tourism presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to move away from the previous paradigm of a focus on ever-increasing visitor numbers and tourism receipts, while the needs of local communities and the natural environment were poorly served. According to the Travel Foundation, now is an opportune time to reverse this pattern and place local communities and the resources they depend at the heart of the recovery planning (Sampson, 2020). To achieve this will require strong destination management, which focuses on collaboration between the local community, residents, and key stakeholders in order to maximize the positive benefits of a thriving tourism sector.

It is important to remember that the travel and tourism industry also has many positive impacts that are less frequently mentioned in the media. These include, an often significant, contribution to local employment, investment in public infrastructure, wildlife conservation as well as protection of natural and cultural heritage assets. The negative social and environmental impacts caused by overtourism tend to arise when destinations become over reliant on the travel and tourism sector and are not well managed. Effective destination management is critical to ensure that the tourism industry achieves a sensitive balance that delivers economic prosperity at local level, but at the same time is also socially and environmentally sustainable.

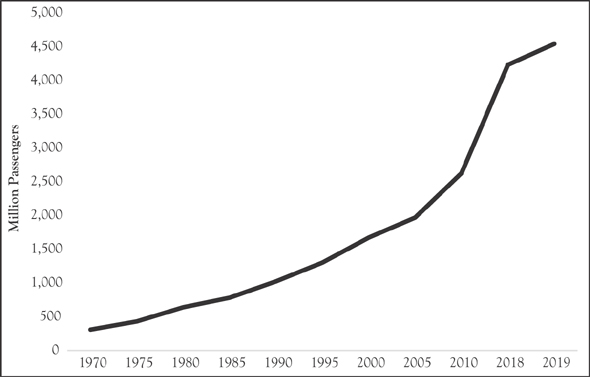

Rapid Growth in Air Travel

The world has become more accessible through more frequent and cheaper air transport, which has led to global mass mobility. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), international air transport grew at double-digit rates from its earliest post World War II days until the first oil crisis in 1973 (IATA, History—Growth and Development 2021). Much of the growth impetus came from technical innovations such as the introduction of turbo-propeller aircraft in the early 1950s, transatlantic jets in 1958, wide-bodied aircraft and high by-pass engines in 1970, and later advanced avionics. These advances brought higher speeds, greater size, better unit cost control and as a result, lower real fares and rates. This combined with an increase in real incomes and more available leisure time led to an explosion in the demand for air travel as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Global air passengers (1970 to 2019)

Source: Worldbank 2020

At any given moment in 2018, an estimated 1.4 million people were airborne on a commercial flight somewhere in the world (Fox 2020). Most were on a short-haul flight linked to a nearby city within the same country as evidenced by the most densely trafficked sector: the 454-km hop from Seoul to the resort island of Jeju, off South Korea’s southern coast. Another major factor influencing the growth in air travel, especially short haul, has been the advent of low-cost airlines such as Southwest Airlines and easyJet. In Europe, the phrase “easyJet Generation” refers to young people who have grown up in a region where cheap aviation and open borders have permitted unprecedented mobility. Since the 1990s the world has seen more people flying than ever before and the act of flying has become a core lifestyle practice leading to global mass mobility. Global mass mobility, due to access to frequent and cheap flights, is considered one of the major causes of overtourism.

While the 20th century saw the creation and rapid growth of the international air transport industry, the beginning of the 21st century was marked by great challenges met with major transformations. Over the last two decades, the aviation industry has been challenged by a number of crises and shocks including terrorism, volcanic eruptions, global economic crisis, and pandemic threats. In spite of setbacks the growth in air travel continued at an exponential rate fueled by developing economies, such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC countries) with improved access and an ever-increasing middle class. Growth is unlikely to level off until these become mature markets. Of course, growth in air travel will continue to be affected by unanticipated shocks such as the coronavirus pandemic, which will have a major short-term impact. However, looking at how the industry has recovered and continued to grow following previous crises events, air travel is likely to bounce back strongly following the current upheaval. For example, the relative drops in passenger traffic were deepest following the combined 2000 to 2001 shock of the dotcom bust and the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and the 2008 shock of the global financial crisis. According to the World Economic Forum, traffic had returned to its trend level within four years continuing to grow in line with the long-term trend. Indeed, after the 2008 financial crisis, tourism was seen as a key driver of economic growth and in turn wealth creation (Calderwood and Soshkin 2019). It is clear that the coronavirus pandemic had a very severe impact on international travel as countries introduced international travel restrictions and bans in order to contain and minimize the spread of the virus.

Historically, the airline industry has been able to adapt its operations and business models in response to crises and external shocks. It cannot be taken for granted that resilience will be automatic. There is a counter argument that air travel will take longer to recover from the coronavirus pandemic and that the quantity and range of flights will shrink considerably especially to smaller regional destinations. It is unlikely that airlift will be restored to the level of 2019 for a number of years. The majority of airlines have been devastated and as a consequence will become smaller. They have had to cut routes which in turn will impact hotels and other tourism-related businesses. Many faced bankruptcy and ceased trading due to lack of cashflow resulting from reduced demand as the pandemic continued to bite. At the end of 2020, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) estimated that the coronavirus pandemic had resulted in air travel demand dropping by 2.89 billion travelers and that gross passenger operating airline revenues fell by as much as USD181 billion during 2020 (ICAO 2021). The limitations resulting from less air capacity are likely to protect destinations against overtourism in the short to medium term with overtraveling reduced due to higher airfares and less airlift capacity.

Growth in Cruise Travel

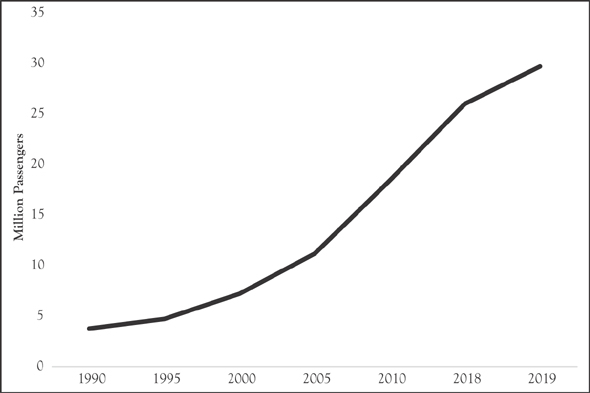

Similar to the growth in air travel, the rapid evolution of the cruise industry has had a major impact on destinations and has increasingly caused congestion in the most popular destinations ranging from Venice to Santorini and from Dubrovnik to Reykjavík.

As early as in the 1850s, ships catering purely for passengers were firmly established but it was not until the 1880s that the concept of cruising took off when ships such as the Mauritania, Lusitania, Olympic, and the ill-fated Titanic were introduced (Smith 2021). These large ships were purpose-built and offered a wealth of luxuries similar to those found in a five-star hotel. In keeping with the time, a class system was established onboard for passengers who mainly traveled for business or immigration purposes. Despite the Titanic’s fate and World War I, cruising began to rise in popularity during the 1920s and 1930s. However, the introduction of air travel by jet after World War II meant that traveling by ship was no longer popular. It was not until 1974 when Cunard revolutionized cruising with the introduction of large-scale entertainment including cabaret acts, international celebrities, high-end production shows, and extensive dining options for leisure purposes that cruising really took off. At the same time, shore excursions were introduced meaning that cruising became a holiday rather than a way of getting from A to B. Unlike other modes of transport, the cruise ship itself became the core element of the holiday experience (Smith 2021).

Since the late 1960s the growth in the number of cruise passengers has been uninterrupted even during the global financial crisis in 2008 to 2009 and the Costa Concordia loss in 2012 off the coast of Isola de Giglio in Tuscany Italy. This incident led to a period of negative PR for the industry (Neate and Bowers 2012). As the fastest growing segment of the travel industry, cruising has come a long way since the 63 passengers that sailed on the Britannia in 1840. In 2010, Royal Caribbean launched the biggest cruise ship in the world the “Allure of the Seas,” which has a 6,000-passenger capacity with facilities more akin to a floating city (Allure of the Seas 2021). Ships are becoming ever larger and more innovative in terms of the facilities and services offered with an average capacity of over 3,000 passengers. The enormous size and capacity of modern cruise ships has a major impact on the destinations visited such as small islands, which can become overwhelmed quickly when thousands of daytrippers descend on a destination within a short space of time.

As may be seen from Figure 4.2, the global cruise industry has expanded rapidly over the past three decades. The number of cruise passengers increased by a compound annual growth rate of 6.6 percent between 1990 and 2018 from 3.8 million to 28.2 million (CLIA 2020).

Some of the most popular cruise regions around the world are North America, the Caribbean, and Europe. The Mediterranean and its adjoining seas have been a major driver of cruise passenger growth over the past two decades (Pallis 2015). As a consequence, cruise ports and destinations face a number of challenges due to the increasing number of passengers arriving, particularly in Europe. While the economic benefits, in terms of spending in destinations can be significant, especially in turnaround ports where cruise passengers join or depart the cruise and therefore tend to stay overnight. However, the sheer volume of cruise passengers descending on destinations in large groups during the day throughout the main summer season (from May to October in Europe) is increasingly causing friction with local residents due to congestion and overcrowding.

Figure 4.2 Cruise passenger evolution (1990 to 2019)

Source: OECD and Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), 2020

There are different views as to how the cruise industry will emerge post the coronavirus pandemic with some suggesting that people will be extremely reluctant to go on a cruise, especially as the main demographic for cruises tends to coincide with those most vulnerable to succumb to COVID-19. On the other hand, some cruise operators have reported a major increase in forward bookings in 2020 compared with the previous year. This would suggest that avid cruisers are not too concerned about taking a cruise in the future. Undoubtedly, cruise operators will innovate quickly to improve safety and hygiene standards for passengers, and this may indeed happen more rapidly than at the destination level. Thus, passengers may feel more secure staying on a ship than in a local unbranded accommodation establishment that may not meet the same safety and hygiene standards.

Tackling Overtourism Caused by Cruise Passengers

Venice is one of the most popular home ports (Conradi 2020) in the Mediterranean and is well-known for the negative effects caused by over-tourism. In 2014 a ban was imposed on large cruise ships passing through the center of Venice, preventing all ships over 96,000 gross tons from sailing the city’s main cruise terminal as well as limiting the number of bigger ships to five a day. Local residents had protested that the presence of the larger ships was increasing pollution and speeding up the erosion of the UNESCO World Heritage city’s medieval buildings that are sinking into the lagoon surrounding Venice. In August 2019, the Italian minister for transport went further and announced that cruise ships would be routed away from the center of Venice to the outlying terminals of Fusina and Lombardia. The decision followed an incident in June 2019 where a cruise ship hit a dock in the city (Roberts 2019). Four people were injured when the ship crashed into a dock and a tourist river boat on the Giudecca Canal, one of the busiest canals leading to St. Mark’s Square.

An access fee of up to €8 for day-trippers was due to be introduced in July 2020 in Venice as the city struggled to manage a tourism industry that sees around 26 million visitors per annum, many arriving by cruise ship. The revenue generated by the fee will be earmarked for public services impacted by tourism such as rubbish collections and street maintenance while locals will see their taxes reduced at the same time. The fee will be collected at the main entry points to the city, which in turn will provide important footfall and tourist flow data for future reference. The entry fee for daytrippers has been temporarily scrapped until July 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic as the city of Venice is now suffering serious financial problems due to the lack of tourism, the main source of income for the city. This demonstrates the economic fragility of a destination that is overly dependent on tourism. Some had been arguing that the introduction of an entry fee for daytrippers was too little too late and that the city needed a more proactive approach to sustainable tourism in order to ensure that locals benefit from the industry. The coronavirus pandemic provided an opportune time for Venice to consider the best way forward while tourism was temporarily on hold.

In an attempt to tackle overtourism, Dubrovnik in Croatia is due to introduce a maximum limit of 4,000 cruise passengers to be allowed ashore daily and from 2022 each will face a charge of €2. The UNESCO World Heritage site known as the “Pearl of the Adriatic” has been struggling with an increasing number of cruise visitors, partly due to the success of Game of Thrones, which was filmed in the city and most of the locations can be visited in a day making it an ideal shore excursion (Connolly 2019). In 2018, Dubrovnik received around three million visitors mainly from about 400 cruise ships that docked at the harbor. It is evident that such a large influx of daytrippers is causing long-term damage to the city’s historical sites while the cruise ships create water, air, and noise pollution affecting the marine ecosystem adversely (Connolly 2019). In addition to the daily charge to be imposed on cruise passengers, Croatia has established a Tourism Development Fund to facilitate the development of public infrastructure in support of visitor attractions in less developed areas and is taking steps to encourage new segments seeking different types of experiences (OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020 | en | OECD 2020). However, there is evidence to suggest that once one destination introduces measures to reduce overtourism then tourists move on to the next destination. In the case of Dubrovnik that may mean Kotor in nearby Montenegro.

On a more positive note, smaller, often more exclusive, expedition cruises tend to be more considerate of local culture and the environment. The Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO) was founded in 2003 and is an international organization for expedition operators who are dedicated to managing responsible, environmentally friendly, and safe tourism in the Arctic—the core areas being Svalbard, Jan Mayen, Greenland, Arctic Canada, the Russian Arctic National Park, and Iceland (AECO 2020). The members agree that expedition cruises and tourism in the Arctic must be carried out with the utmost consideration for the vulnerable natural environment, local cultures, and cultural remains, as well as challenging safety hazards on sea and on land. Members encourage incorporating specific standards and guidelines for operating expedition cruises in the Arctic. Furthermore, it recommends the use of highly qualified guides and staff knowledgeable and experienced in the Arctic environment, its natural and human history and contemporary culture. The AECO network currently includes 76 members, 40 passenger vessels, and 10 yachts, which handled over 25,000 expedition cruise passengers in the Arctic in 2018 (AECO 2020). The polar expedition cruise industry is expanding with 30 new vessels anticipated within the next five years with advanced vessel structure and technology, new operators, and new itineraries. Among Arctic expedition cruise destinations, the most visited is Svalbard while Alaska and Iceland are already seeing a large number of expedition and conventional cruise passengers. Clearly future growth will represent challenges in the Arctic which AECO’s members are anticipating and seeking to mitigate through better research to inform knowledge-based tourism management.

Cruises are seen by many as being worse than “all-inclusive” holidays as they encourage mass tourism due to the sheer number of passengers on each ship, which in turn can lead to overtourism. Passengers typically spend little money in the destinations they visit as excursions are paid for as part of the cruise package and not at the destination level. Destinations need to proactively manage and segment cruise ships in order for the sector to work optimally in terms of maximizing socioeconomic benefits. Environmentally fragile niche destinations such as Svalbard, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands need to carefully consider what types of cruises they want, when, and how many in order to maximize the economic impact and minimize any negative impacts such as environmental degradation caused by large volumes of cruise passengers all arriving during a short period of time. This can be particularly overwhelming in sparsely populated remote locations. The work of AECO demonstrates that a carefully managed cruise industry can be positive as long as the scale and size of ships are appropriate to avoid congestion and pinch points arising. Small expedition-style cruises a la Compagnie du Ponant can accommodate visitors to more remote areas such as Svalbard and Greenland, which are difficult to access and offer limited tourist accommodation on land. Such remote and inaccessible places have difficulty in sustaining visitor numbers year-round, which means that investment in onshore tourist accommodation is often not viable. The main value is in offering imaginative and innovative excursions that involve and benefit the local community.

The Svalbard Environmental Protection Fund was established in 2007. The fund’s primary source of income is an environmental tax of NOK150 levied on everyone visiting Svalbard. The fee is automatically added to the ticket price, so the majority of tourists are unaware of it (AECO 2020). This seems a missed opportunity to communicate and promote the important role and work of the fund. Today, the fund supports projects and interventions to conserve and protect the natural and cultural environment of Svalbard of around NOK 20 million per annum (AECO 2020). The purpose of the fund is not to facilitate the growth of tourism, but rather to help mitigate any negative environmental impacts caused by tourism and other traffic. Grants are also provided to support research and studies to identify and monitor the environment and causes of environmental impacts as well as to inform, educate, and facilitate environmental protection in the broadest sense.

Major Drivers of Overtourism

As described in the previous sections, the exponential growth in international air and cruise passengers is a major contributory factor to the rise in overtourism. Responsible Travel considers the real cause of overtourism to be the collusion between airlines, cruise ships, and governments to create artificially cheap flights and cruises at the expense of taxpayers and the environment. For example, it is not uncommon today to be able to purchase a short-haul European flight to Barcelona for less than the cost of a meal out. It is worth noting that in 1944 the aviation industry sealed a deal known as the Chicago Convention that made aviation fuel exempt from tax (Frances 2020). Similarly, the cruise industry uses one of the cheapest types of diesel known as “bunker” fuel. This type of fuel is highly polluting and causes public health risks and thus would not be allowed on land. It enables cruise lines to keep costs low and invest in ever larger new ships. However, destinations such as Copenhagen who are proactively looking to tackle climate change are seeking to make it mandatory for cruise liners to use sustainable sources of power while docking at Copenhagen Malmø Port (Wonderful Copenhagen 2020).

Iceland is a prime example of how the combination of growth in visitors arriving by air and cruise have been a major contributory factor to overtourism, particularly in Reykjavík during the peak summer season. Iceland has a small population of just over 364,000 of which the majority 233,000 live in the Reykjavík capital region (Statistics Iceland 2021). Iceland was at the center of the global financial crisis in 2008 when its banks failed leading to a collapse of the housing market and a tripling in unemployment resulting in a bailout by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Sheivachman 2019). A weakening of the Icelandic Krona made Iceland more affordable to travelers and this combined with the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 made Iceland a global tourism hotspot in large part due to excellent airlift via the national carrier Icelandair. In 2019, Iceland received just under two million international visitors arriving by air through its main hub Keflavík Airport—this was decrease of 14.2 percent on the previous year—but still almost a quadrupling from just over half a million in 2001. The decrease in international tourists in 2019 was due to the strong Krona making Iceland more expensive and the collapse of budget carrier WOW. In addition, cruise passenger arrivals at Reykjavík have increased at an even faster rate from around 28,000 in 2001 to 144,000 in 2018 (Statistics Iceland/Visit Iceland 2020). This combined with the coronavirus pandemic meant it was a good time for Iceland to pause and take stock on the future shape of its tourism industry.

Warnings about overcrowding were voiced as early as 2011 and as tourism continued to grow rapidly overtourism became a reality in Iceland. Its relatively small host population has been struggling to cope with an ever-increasing influx of visitors despite the economic boost the tourism industry provided. Icelanders were rightly concerned about this and there was a growing feeling that as the industry matured, it was time to decide how tourism could become more sustainable in the long term. In 2018 to 2019, destination management plans were published for the seven regions in Iceland with a view to establish a DMO in each with a view to improving the coordination of tourism priorities and regional development as well as act as a support unit for data collection, innovation, product development, skills, digitalization, and marketing (OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020 | en | OECD 2020).

Consequences of Growth in International Travel

The continued growth in international travel has raised questions around how travel and tourism can best be managed to the benefit of all people, places, and businesses. While at the same time mitigating any adverse impacts on the cultural fabric, natural, and built environment in destinations across the world. The OECD advocates that:

there is a need to rethink tourism success for sustainable growth. In particular, it encourages policy makers to take steps to help destinations avoid pitfalls, as they strive to strike a balance between the benefits and costs associated with tourism development and implementing a sustainable vision for the future (OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020 | en | OECD 2020, p. 11).

So, while overall growth in tourism is considered positive by the OECD, it also recognizes that governments increasingly need to develop urgent policies that seek to maximize the economic, environmental, and social benefits while at the same time seeking to reduce the negative impacts and pressures that can arise when growth is unplanned and unmanaged.

Social Media and Technological Advances

The digital revolution has been a significant contributor to the growth in tourism in terms of changing the way people travel and purchase services as well as how products are promoted and advertised. Trends include an increased use of online resources and mobile platforms to source information when planning a trip, be it websites or social media, combined with a decreasing use of offline sources such as brochures and travel guides. Advances in online booking platforms, peer-to-peer review sites, and online guides and mapping tools have made traveling much easier and faster as these allow tourists to pick up information quickly about top local attractions and current activities, which in turn may stimulate hot spots and overcrowding. The EU Tran Committee research study on overtourism identified such technologies as having the potential to accelerate growth in volumes and tourist flows in some locations leading to overcrowding and in turn overtourism (Peeters, et al. 2018, p. 24).

Furthermore, social media and other technological advances such as artificial intelligence and machine learning are driving travel and tourism behaviors of the millennial generation. In particular, the “bucket list” is a major trend focusing on visiting the most accessible and renowned sites, which can lead to overtourism if visitor flows are not managed effectively. It is crucial for destinations to be aware of as well as value and protect their “bucket list sites,” which tend to be the most appealing attractions that can quickly become congested and fall victim to overtourism. Social distancing measures introduced during the coronavirus pandemic will likely mean that destinations will be quicker to introduce technological monitoring to ensure that key locations do not become overcrowded. For example, destinations can learn from museums and visitor attractions, which track visitor numbers and sell timed tickets to avoid overcrowding at peak times. Equally, such an operating system can be applied to public spaces and cultural events.

Sharing Economy

The “sharing economy” is perhaps the most significant trend to emerge over the past decade with the emergence of new online digital platforms for short-term rentals such as Airbnb and HomeAway as well as the more recent inclusion of short-term rentals on platforms such as Booking.com. This has resulted in the market growing at an unprecedented rate and outpacing the growth of traditional modes of tourist accommodation including hotels and guest houses. With the help of new technologies, the traditional cost of doing business has decreased significantly enabling both private individuals and smaller commercial enterprises to partake.

Consumers increasingly value experiences such as travel. Apart from value for money, consumers seek authentic, local, and unique experiences. These trends have led to the phenomenal success stories of sharing economy brands like Airbnb in addition to a growing interest in activity-based travel according to Euromonitor International (Geerts 2020). Tourists are increasingly in search of authenticity and unique experiences, which sometimes mean “discovering” lesser-known neighborhoods and destinations in order to live like a local. According to the EU Tran Committee research study evidence, there is a correlation between a high number of Airbnbs in residential areas and increasing negative social impacts associated with overtourism such as noise (Peeters, et al. 2018). The arrival of Airbnb has exposed poor regulations and control of the local housing market in a number of destinations. This in turn has exacerbated the issue of too many tourists in local residential areas. However, Airbnb has recently stated its commitment to collaborate with DMOs and local authorities to ensure that local housing markets are not distorted by short-term holiday lets.

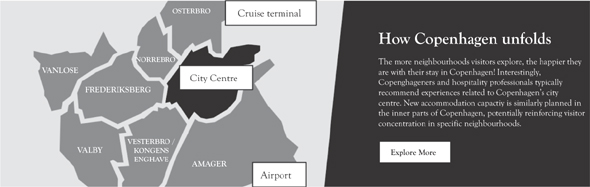

In the case of Copenhagen, it is thought that the DMO Wonderful Copenhagen’s desire to deliver local authentic experiences could be at the expense of locals. This was highlighted by Lonely Planet suggesting that the city had fallen victim to overtourism with local residents increasingly concerned about the growing number of visitors and increasing noise levels (Brady 2019). Like many other popular European cities, Copenhagen has experienced a meteoric rise in overnight tourist arrivals increasing by 74 percent over the past decade and reaching 8.8 million overnight stays in registered accommodation in 2018, excluding an estimated 1.9 million Airbnb stays. On top of this comes cruise passengers of which there were 868,000 in the same year as well as other daytrippers (Brady 2019). Wonderful Copenhagen is forecasting that the number of tourist arrivals will double by 2030 to reach an estimated 16 million overnight stays. However, part of the future strategy “10xCopenhagen” is based on a two-pronged approach to disperse visitors better throughout Copenhagen and the northern part of Zealand as well as by season. Geographically, Copenhagen is divided into a relatively compact central city area as well as five adjacent outer areas where the majority of the local population live, all offering a distinct neighborhood feel. Vesterbro home to the red-light district and the former meatpacking area is a case in point as may be seen from Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Billboard promoting the Vesterbro area of Copenhagen

Source: Helene Møgelhøj, Copenhagen Airport August 2020

For many years the majority of tourists visiting Copenhagen would only have visited the city center, but this is starting to change due to the DMO’s successful efforts to get people to visit other parts of the city in order to enjoy a local and authentic experience as well as a rise in the number of Airbnb properties available. These are typically situated in the outer areas as this is where the biggest concentration of local housing is found as shown in Figure 4.4.

However, Wonderful Copenhagen and the City Council are well aware of the issues and frequently engage with the local community and other stakeholders so that issues are addressed on an ongoing basis to ensure that any negative impact on the residents’ quality of life is minimized. This is backed up by research, which suggests that 67 percent of local residents in Copenhagen experience no problems with the city’s tourism and overall remain positive about welcoming even more visitors to Copenhagen in the future. Only 6 percent of those surveyed cited that there were often problems due to tourism in the city including noise, traffic congestion, and litter/waste (10xCopenhagen 2020). Indeed, Wonderful Copenhagen, has a dedicated project manager tasked with sustainable tourism development in the city.

Figure 4.4 Map of key areas and locations in Copenhagen

Source: 10xcopenhagen.com 2020

Unusually, for a DMO, Wonderful Copenhagen’s 10xCopenhagen strategy includes a substantial focus on Copenhageners’ perception and experience of tourism in their daily lives, in addition to research on the competitive position of Copenhagen’s tourism product as well as the future drivers of tourism growth (10xCopenhagen 2020). The strategy makes the following recommendations in order to make the city even better:

• Create a program to develop decentralized tourism strategies and measures of success, cocreated between the local community, local industry, city and tourism developers. Address more aspects of the value creation of tourism—with relevance and direct impact on local lives.

• Make channels available for Copenhageners to identify and voice tourism-related issues and opportunities on an ongoing basis.

• Establish a task force to address top locations or aspects of the locals’ experience of tourism-related traffic issues (10xCopenhagen 2020).

The strategy goes on to suggest ways to make Copenhagen expand to accommodate the anticipated increase in the number of tourist arrivals.

• Include sustainable tourism growth as a relevant element in urban planning, as well as a positive tool to strengthen the appeal of more city areas and neighborhoods to locals and visitors alike.

• Consider new ways to incentivize investment and initiatives that spotlight Copenhagen as an attractive destination beyond the center of the city.

• Develop visibility and visitability of attractions outside the inner-city area, using a lighthouse strategy to make experiences around attractions more accessible to visitors.

• Enable better, broader, and more personal recommendations where credibility and opportunity exist (within hospitality, events, transportation, etc.) (10xCopenhagen 2020).

Airbnb

At the end of 2020, Airbnb was represented in more than 100,000 destinations and over 220 countries with total worldwide listings in excess of 7 million facilitated by around 4 million hosts (Airbnb 2020). Airbnb has been the subject of much discussion in relation to overtourism over the last couple of years as well as accused of causing rising rents and housing shortages for local residents as professional landlords chose short-term Airbnb rentals over long-term local tenants. Furthermore, most hoteliers tend to view Airbnb as an unregulated operator selling tourist accommodation at a low price, thus distorting the traditional visitor accommodation environment in any given location. Tourist boards and traditional hoteliers warn that there is no safety, quality control, or brand reassurance and the owners may not be paying sufficient tax. Of course, the arrival of Airbnb has exposed the inherent weaknesses of poorly regulated and controlled housing markets in destinations around the world leading to rents and real estate prices being inflated driven by professional landlords letting multiple properties and in turn contributing toward overtourism.

Mainly, Airbnb has been treated a bit like an OTA (online travel agent), that is, a very successful and disruptive booking engine undermining the traditional accommodation sector distribution channels. In reality Airbnb is so much more than that. Yes, for some it may be about finding a bed or a room at the lowest price in the right location, but it can be argued that for many consumers it is about much more. This is frequently illustrated by the no end of fashionable social media influencers and bloggers staying in a diverse range of unique and photogenic Airbnbs across the globe confirming the often not insignificant visual appeal of the properties on offer. In fact, Airbnb is not particularly fast and efficient when it comes to making a booking, as this often requires a fairly extensive dialogue with the owner before any confirmation is made. Both parties can ask questions and look at each other’s profiles and reviews prior to making a commitment. Like Uber, Airbnb is rooted in the sharing economy, which is driven by technological platforms that have enabled worldwide sharing of services between people who do not know each other at a relatively low cost. Thus, at its core Airbnb is about sharing travel experiences and spaces for mutual economic benefit. It is not about a cookie cutter quality-controlled and brand-reassured homogenous experience, but rather about engaging with local people in their environment, because usually the host is more than happy to introduce guests to their favorite places within their local community. In essence local people become the destination’s ambassadors. Obviously, this also has a downside as this means more tourists end up staying in what are predominantly residential neighborhoods such as in the Copenhagen case described earlier.

Despite all the warnings millions of hosts and consumers have bought into the Airbnb concept, so it is clearly working regardless of the criticisms. If nothing else, it has certainly acted as an innovation stimulant in the more traditional accommodation sector. Indeed, boutique and luxury hotel brands have started using guided selling tactics that blend content and personalization to foster a deeper engagement with the destination and encourage direct bookings.

However, the coronavirus pandemic means that many of the “so-called” professional landlords have switched to other platforms aimed at longer rentals, which are likely to be more beneficial to local residents. According to Wired, the city of Prague used the coronavirus pandemic as an opportunity to take back control of its short-term rental market in order to increase the supply of housing available to local residents (Temperton 2020). No doubt other major cities will follow suit in order to try and redress the balance between short-term visitor accommodation and housing for local residents. It is likely that the coronavirus crisis will result in a much leaner Airbnb, which will hopefully be more aligned with the original vision and getting back to its roots of providing short-term accommodation with an opportunity to live like a local and engage with the local community. Indeed, in an interview with the Sunday Times Magazine, one of Airbnb’s founders Brian Chesky recognized some of the mistakes made by Airbnb and apologized with a promise to reset and go back to the “roots, back to basics, back to what is truly special: everyday people who host in their homes” (Arlidge 2020).

According to the Dutch Review, Amsterdam banned Airbnb from 1 July 2020 in certain central parts of the city in order to avoid returning to the overtourism experienced prior to the coronavirus pandemic. In other parts of the city Airbnb will continue to be allowed subject to a special permit and for a maximum of 30 days per annum for groups of no more than four people (Lalor 2020). These measures are widely supported by the stakeholders and the local community with 75 percent of the 780 inhabitants and organizations surveyed in favor. The coronavirus pandemic has provided local people with an opportunity to get to know their city and its neighborhoods without tourists and with a lot less noise, something the authorities are keen to preserve going forward.

Lisbon has taken a different approach to ensure that local housing stock is no longer primarily used as Airbnb rentals. Up to a third of the housing in Lisbon’s historic core was used by Airbnb prior to the coronavirus pandemic. Fernando Medina, the city’s mayor, has utilized the coronavirus crisis to ensure a proportion of Airbnb-style properties are turned into affordable “safe rentals” for local people including key workers and the elderly who are often threatened with eviction and faced with having to move out of the city center (Medina 2020). In 2020, the city offered to pay landlords, many of whom had mortgages to pay but few visitors, to turn Airbnb-style rentals into safe rentals thereby prioritizing affordable housing and protecting local communities as well as the city’s unique character. This is not intended to turn future tourists away, but rather to improve local people’s quality of life in Lisbon with a view to creating a more vibrant, healthier, equitable, and in turn greener city by reducing local residents’ need to commute. Landlords will be required to sign two- to five-year leases and are unlikely to be able to return to letting their property to tourists even in the long term.

It seems that Airbnb is not the root cause of overtourism and displacement of local residents although it may have been a contributory factor. In fact, this has more to do with regulation and control of local housing markets where weaknesses with regard to subletting have been exposed and taken advantage of by landlords and tenants. This is something Airbnb is fully aware of and has vowed to tackle in collaboration with city councils and DMOs.

Authenticity and Experiential Travel in a Digital World

In recent years, there has been a growing demand for adventure and experiential travel with tourists seeking out unusual and unique experiences. On the whole consumers, especially millennials, are looking for more authentic experiences that connect with the local community in terms of arts, culture, and gastronomy thus providing a more memorable personalized experience. In general, the goal of experiential travel is to have an immersive experience and gain a fuller understanding of the destination. Experiential travel is closely linked to the search for authenticity and localism. Technology and sharing economy platforms have provided people with the tools to plan and design their own trips and experiences. It is not surprising that destinations such as Iceland have seen growth in visitor numbers due to this trend, as it offers a plethora of outdoor activities from heli-skiing to glacier and volcano hiking and from whale watching to horse trekking, providing a wide variety of experiences in a short space of time to some of today’s cash-rich time-poor travelers. Furthermore, many experiential experiences are provided by passionate innovative entrepreneurial micro and small businesses making them a great way to engage with the local host population.

Recent research by the European Travel Commission emphasized the importance of pursuing hobbies and interests as a driver of tourism, with gastronomy, adventure, urban experiences and “living like a local” resonating with most visitors (European Travel Commission 2019). In terms of gastronomy, travelers are keen to seek out hidden gems such as places that have long been favorites among locals and offer sought-after home-grown flavors. Advances in digital technologies and social media have made it much easier to discover and share such experiences.

The digitalization of travel and tourism was initially thought to encourage wider dispersal of visitor flows. In reality, it has turned out differently due to the powerful influence of social media, which has had a homogenizing effect stimulating the desire to visit bucket list destinations from Italy’s Venice to the Lima’s Machu Picchu and from the Great Wall of China to Nepal’s Mount Everest, resulting in overtourism in an increasing number of destinations. According to the WTTC 2018 report on overtourism this trend is particularly pronounced among first-time international millennial travelers who use social media to show off (McKinsey & Company 2017).

In the case of Nepal, the effects of overcrowding have been deadly as reported by the Guardian newspaper on May 11, 2019, 11 climbers died attempting to reach the Mount Everest Summit owing to more than 100 climbers queuing up to ascend the crest (Gentleman 2020). According to experienced mountaineer Nirmal Purja:

such bottlenecks have been troubling the mountain with increasing frequency. The deaths were not caused by the queue itself, but a different problem: the rising numbers of inexperienced climbers who view Everest as the ultimate selfie destination, and the proliferation of companies willing to take their money and let them have a go, regardless of their ability.

This despite the USD11,000 permit required to climb the mountain, and package prices ranging from around USD30,000 to USD200,000. In 2019, 381 permits were issued, an increase of 35 over the previous year. The Nepalese Government is fully aware of the situation and are considering introducing more stringent measures to ensure that people issued with a permit are physically capable of reaching the summit as well as restricting the number of climbers that can attempt the summit on any given day (Gentleman 2020). However, the coronavirus pandemic has left Nepal’s tourist industry devastated and may have reduced the Government’s willingness to impose more robust regulations at least in the short term. Many of the cooks, porters, and guides whose livelihoods depend on the climbers were left with no income and have had to return to their villages due to the absence of tourists.

Until recently, the impressive chalk cliffs at Seven Sisters were mostly known for Beachy Head’s unfortunate reputation as a suicide spot and being a popular site for local ramblers. The iconic Seven Sisters’ wall of chalk is located within the South Downs National Park in East Sussex, England. Today, Seven Sisters is world famous due in no small part to the power of social media. According to an article in the New York Times the cliffs have become extremely popular with Chinese and South Korean visitors after being featured on an online travel site popular with younger Chinese travelers as well as in a video featuring a South Korean actress standing close to the cliff edge (Tsang 2018). Asian visitors primarily come to the UK to visit London and imagine that Seven Sisters is close by, when in reality it is at least a two-hour journey to reach them from the capital. They come to visit mainly because they have seen Seven Sisters appear on social media or in films, especially Harry Potter and Atonement, and by recommendations from celebrities. The rapid influx in visitor numbers from Asia is both an opportunity and a threat. On the one hand if they can be persuaded to stay longer and spend money locally that is a good thing, but on the other hand they are putting increasing pressure on the fragile cliffs, which often experience cliff fall due to erosion making it dangerous to go close to the edge. In 2017, a tourist sadly died after losing her footing too close to the cliff edge.

It is worth noting that during the first weekend in May 2020 after easing of the coronavirus lockdown in England, Seven Sisters was flooded with visitors, and local residents were quoted stating that they had never experienced so many visitors before (BBC news 2020). This illustrates that overtourism is not necessarily caused by foreign visitors, nor by overnight tourists, but can indeed also be caused by domestic daytrippers who may spend very little in the destination visited. In fact, most cases of overtourism are caused by a combination of international and domestic day and overnight visitors, which highlights the need for destinations to carry out regular visitor surveys and monitoring in order to segment their visitors and tailor destination management strategies and actions accordingly.

The “Greta effect,” named after the Nobel Peace Prize winning teenage Swedish activist Greta Thunberg who became the face of the Generation Z environmental movement, means that sustainability has risen toward the top of the travel and tourism agenda. Globally, the tourism sector accounts for up to 5 percent of carbon emissions according to the UNWTO (Euromonitor 2019). The “Greta effect” is stimulating positive changes in attitudes and behavior both at the destination and the consumer level with an increased desire to find solutions to mitigate the negative impacts of tourism on people and the environment.

The coronavirus pandemic has provided people with time to reflect on their travel behaviors and to experience an extended period without the opportunity to travel for nonessential purposes. This has not dampened the overall desire to travel and experience other places and cultures, but perhaps rather highlighted the need to make travel matter and to take fewer but more meaningful journeys involving flying. Having experienced less noise and air pollution for a period of time while facing higher prices and increased waiting times at airports due to stringent health checks and quarantine measures, people are thinking twice about embarking on, yet another short-haul city break to a potentially overcrowded urban destination.

The term flygskam (or flight shaming) as the Swedes call it seems even more relevant now. This is likely to result in more staycations involving travel by train or car. Carbon reductions and sustainability were becoming critical issues for the travel and tourism industry prior to the coronavirus pandemic with customers increasingly expecting measures to be in place without necessarily being willing to pay for these. Conde Nast Traveller is advocating that “it is time to make a practical and personal shift to travel better—better for communities in the places we visit, better for us to connect with destinations in positive and meaningful ways, and better for the natural world.” Conde Nast Traveller’s ten ways to be a better traveler post the initial coronavirus pandemic lockdown include (Mathieson 2020):

1. Take more staycations

2. Buy fewer toxic travel products

4. Consider slow travel

5. Consider locals

6. Stay at hotels rooted in the community

7. No more animals

8. It’s not just about the carbon footprint

9. Travel to the right destinations

10. Aim for low-volume tourism (Mathieson 2020)

A similar message is promoted by the WTTC who recommends that individuals consider the following points to become more responsible and sustainable travelers (WTTC 2017):

• Educate: Spread your knowledge and approach by making responsible tourism choices.

• Talk: Share with others and use their knowledge to increase your own.

• Learn: Develop curiosity about the ways you can be part of the solution.

Consumer research by Euromonitor International indicates that consumers are particularly conscious of social and environmental sustainability with an elevated focus on inclusivity and localism (Euromonitor 2019). Although, consumers are increasingly aware of sustainability and responsible travel it seems that there is a disconnect with the vast majority of travel and tourism operators who are not engaging to the same extent with the sustainability agenda. In general, the travel and tourism industry has been slow to respond to the changing consumer preferences.

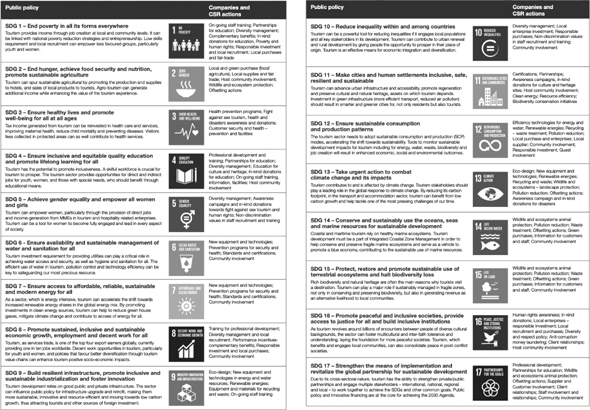

From a destination management perspective tourism has a vital role to play in achieving the United Nation’s (UN) 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as highlighted by the UNWTO, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the UN. These organizations recommend that destinations and tourism stakeholders take action to accelerate the shift toward a more sustainable tourism sector by aligning policies, operations, and investment with the SDGs (UNWTO 2020).

The most significant SDGs in relation to tourism are SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG14 (Life below Water). Although, owing to the travel and tourism sector’s link with other sectors and industries it can accelerate progress toward all 17 SDGs. The SDGs and their relevance to tourism destination management and development are listed in the Figure 4.5 prepared by the UNTWO (UNWTO 2020).

Figure 4.5 Tourism links with the SDGs: public policy and business actions

Source: UNWTO 2017

The second version of the GSTC’s Destination Criteria has been updated to reflect the 17 SDGs and how a destination can contribute toward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (GSTC 2020). Against each criterion, one or more of the 17 SDGs is identified, to which it most closely relates. According to the GSTC, the criteria relate to a place, not a body; however, many of the criteria may be taken up by a DMO to ensure a coordinated approach to sustainable destination development. Overall, the criteria are structured in the following four areas providing a range of indicators to be complied with for destinations to achieve the accreditation:

1. Sustainable management

• Management structure and framework

• Stakeholder engagement

• Managing pressure and change

2. Socioeconomic sustainability

• Delivering local economic benefits

• Social wellbeing and impacts

3. Cultural sustainability

• Protecting cultural heritage

• Visiting cultural sites

4. Environmental sustainability

• Conservation of natural heritage

• Resource management

• Management of waste and emissions (GSTC 2020)

It is clear that the coronavirus pandemic has provided destinations and DMOs with time to reflect on how best to recover and regenerate from the devastating coronavirus pandemic. This should help guarantee that the tourism industry emerges stronger, more sustainable, and resilient in order to ensure that the local host population derives maximum benefits without facing overtourism in future.

Staycations and Localism

According to Wikipedia a staycation, or holistay, is a period in which an individual or family stays home and participates in leisure activities within driving distance of their home and does not require overnight accommodation. They tend to increase in popularity during periods of uncertainty and economic crisis. The term staycation is now used widely not only in the United States and UK, but also throughout mainland Europe.

In the UK, where the staycation phenomenon first emerged following the global financial crisis in 2008 to 2009, it is defined as a holiday taken in the UK by British residents and includes all holidays away from home whether that be a day trip, weekend break, a two-week holiday, or a shorter retreat with more than half of all adults in the UK staycationing in 2017. According to research by Visit England the latest available figures show that there were 59m staycations in the UK in 2017; an increase of 6 percent over 2016. Total spend reached £23.7 billion, up 3 percent in 2016 (Visit England 2017).

On the surface, it may appear that the staycation is a simple substitution, with people switching to a holiday at home rather than going abroad. However, research by Visit England suggests that it was more complex than that. The growth in domestic holidays was not purely driven by necessity, but also by a group called “extras.” Extras may be described as those who started taking more domestic holidays while cutting back on international travel, but at the same time driven by a growing interest in localism and authenticity.

Staycations typically include city breaks, cultural holidays, culinary and spa holidays, which are less seasonal and therefore more likely to be taken throughout the year. Destinations that are able to create itineraries around these themes are likely to be able to stimulate visitation outside the peak season. Clearly, staycations are set to become even more popular following the coronavirus pandemic as they do not tend to involve flying nor traveling abroad. Indeed, many prefer to stay hyper local in the short term, only traveling relatively short distances by car or train. Staycationers are also likely to seek out local food and drink as well as local art and cultural experiences.

Although, it was expected initially that many British residents would choose a staycation over traveling abroad during summer 2020, the early indications were not very clear. Early data analysis by Visit Britain (Visit Britain 2020) suggested that self-catering in rural and coastal areas performed very well. However, hotels and other serviced accommodation in city centers and urban areas continued to suffer and as of the end of 2020, it did not look like the recovery would be rapid due to the continued absence of international and business travelers. Ongoing changes to quarantine and self-isolation measures resulted in significant delays with regard to the resumption of international travel. However, the arrival of a number of COVID-19 vaccines toward the end of 2020 was a cause for optimism with regard to the return of international travel in 2021.

Second City Traveler

Booking.com is predicting the rise of “the second city” traveler, meaning the exploration of lesser-known destinations in a bid to reduce overtourism and protect the environment, will take a leap forward in the coming years. Second city travelers are keen to swap destinations if they may lead to less of an impact on the environment or indeed would have a positive impact on the local community. The coronavirus pandemic also made consumers focus more on rural as well as sun and beach destinations where social distancing can be practiced with relative ease as opposed to more densely populated urban centers.

The coronavirus pandemic accelerated the pace of technological trends that were already happening with online and virtual becoming more important than before as well as the desire to explore destinations closer to home.

Key Takeaways

• The rapid growth in international air travel and cruise over the past five decades are major contributory factors in overtourism.

• Increasing affluence and aspirations will continue to drive growth in international travel in the long term.

• The sharing economy, social media, and other technological advances are driving growth sometimes leading to the creation of bucket list hotspots.

• The demand for local, authentic, and experiential travel can sometimes result in tensions with the local host population.

• Increasing consumer awareness of sustainability, especially social and environmental, but so far businesses have been slow to respond.