Good businesses attempt, as much as possible, not to run on gut instinct or opinion. Instead, they try to be data-driven in as many aspects of the business as possible. Being data-driven can be difficult: as humans, we are strongly guided by our experiences, and the opinions those experiences help us to form. So even in ordinary, day-to-day, team-level thinking and decision-making, it’s important for us to step back and let data be our guide.

15.1 In business, never “believe”

I can’t speak for other languages, but in American English we use the word believe a lot. I actually find it a little problematic, in part because I like to split hairs over words, but in part because the word is not specific enough.

For me, the word believe refers to something that I accept as a fact, even though I have no data, evidence, or other proof of it being true. Religion is something that involves belief, for example. There is nothing wrong with believing in something. However, even I tend to use the word more colloquially at times: “I believe it’s going to rain.” Technically, if I’m looking at a giant storm cloud and the barometer is falling, I don’t need to believe in the rain. I have some evidence that it’s coming.

That’s why, in my working life, I try very hard not to use the word believe. After all, the business isn’t (or shouldn’t be) interested in what I accept as fact without proof, right? The business should be interested in what I’m thinking based on the facts and evidence around me. I don’t want anyone at work to accidentally assume that I’m proposing to make decisions not based on facts, and the word believe suggests that I might be. So to avoid any potential confusion, I try to use other words.

If I have a set of evidence that seems to be pointing in a particular direction, I will express a theory: “I have a theory that we need to change our product in this way.” Theories can be debated, and they can be tested. I can work to assemble additional evidence to prove or disprove my theory. Using the word theory indicates that I’m willing to engage in the prove-or-disprove process, and that I’m not anchored to my statement as an indisputable fact.

I also feel free to state opinions : “In my opinion, we should refactor the code into the following modules, and here’s why.” My opinions are formed in large part from my experiences, which count as data points. I can share those experiences with others, and we can debate their applicability to the current situation. We may not be operating from hard facts, but we’re attempting to learn from history, which is always a great idea in business. Using the word opinion indicates that I may not be working entirely from hard facts, but that I’m integrating my own experience, as well. I’m fine with other people having differing opinions, and we can discuss them.

I will also state facts : “Our user satisfaction score dropped ten points last quarter.” Factual statements are backed up by data, and they form the strongest basis for forming theories and opinions. My team and I might debate the veracity of that data—essentially expressing a theory about its validity—and we can then work to prove or disprove it. Using the word fact indicates that I’ve accepted a data point as objectively true. That lines up everyone else to either also accept the fact, or to challenge its veracity, either of which lets the team move the discussion forward.

These are, for the most part, the only statements I’m comfortable making at work, especially when decision-making is involved: theories, opinions, and facts. I try to steer clear of beliefs, because others may have different beliefs. Because beliefs aren’t necessarily rooted in objective, shared data, it’s difficult for people to debate beliefs and apply them to the world of business.

15.2 Be a data-driven, critical thinker

Critical thinking is an exercise in which you deliberately try to remove your own filters, biases, and beliefs from a situation. Instead, you try to think about it solely in terms of the data and hard facts that you have or are able to gather.

For example, let’s apply critical thinking to a question: Why can’t women play American baseball alongside men? When I pose this question, I often hear instinctive reactions in response: “Men are stronger,” or “Men are much faster,” or “Men can throw farther” or similar. But there are no facts to support those statements. In fact, quite the opposite is true: there are some women who are faster than some men, some women who are stronger than some men, and some women who can throw farther than some men. If we were to think critically about the question, we could arrive at a theory like, “Because American society has long-held cultural biases about women’s athletic abilities compared to men.” That’s a theory which could be examined and, in time and with sufficient facts, likely could be proven or disproven. It might not be a comfortable theory for everyone involved in the conversation, but critical thinking is about arriving at objective answers, not about making everyone feel comfortable.

The key to critical thinking is basing your thinking on facts. Tear apart whatever statements you’re making or considering, and for every element ask yourself: What facts do I have to support this? Where did those facts come from? Am I accepting anything as fact, without knowing the origin of, and basis for, that fact?

In being a critical thinker, you’ll often find yourself without the facts you might need. In those cases, it’s fine to state a theory. A theory is kind of like a proposed fact, or a proposed set of facts: “Given what facts I do have, I suspect that the following facts might also exist.” But in critical thinking, you can’t stop with just a theory! You have to then work to prove or disprove the theory. Once a theory has been proven, it becomes a new fact, and you can proceed.

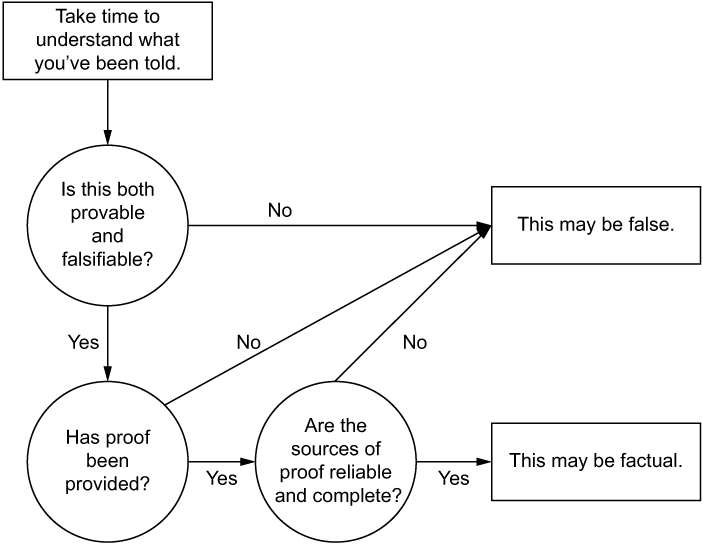

If you’re a visual thinker, consider figure 15.1 as an illustration of a high-level critical thinking process.

Figure 15.1 A critical thinking process

Let’s highlight the key bits from that figure:

-

Falsifiable—If someone offers you something that can’t be proven, and/or can’t be disproven, then they’re not stating a potential fact; they’re stating an opinion. You can choose to adopt their opinion or not, of course, but don’t confuse that with facts. For example, if someone says, “Aliens never landed at Area 51 in the American desert,” that’s an opinion. It can neither be proven nor disproven by experimentation and evidence.

-

Proof—If someone is offering a theory, then they either need to provide proof, or you need to obtain that proof on your own. Facts that are not backed up by evidence are not facts, they are opinions.

-

Reliable and complete—This one is critical! Examine the proof that’s been provided to you. Did it come from reputable sources who have nothing to gain either way? That is, are they unbiased? Are the sources of the proof reliable—have you heard of them before, and found their work to be accurate? And most importantly, are the proofs you’re given complete? It’s easy to “prove” almost any argument by presenting only those facts which support the desired conclusion. True critical thinkers seek out contrary evidence and weigh everything.

Now let’s go over a couple of examples. Here’s the first one: suppose you’re watching a politician making a statement on TV. You happen to favor that politician—perhaps you voted for them, or you like where they stand on certain issues. The politician says, “I would be happy to provide a list of candidates for the appointment we’re discussing, but the government administration has never asked me for such a list.”

Many people would hear such a statement and immediately believe it, simply because they’re positively disposed toward the politician. They might become angry at the government administration. Other people would automatically disbelieve the politician, perhaps because they’re not favorably disposed toward them. All of those people are failing to think critically, which (I theorize) is probably where most of the world’s political problems come from. A critical thinker would analyze the two statements the politician made:

The first statement is an opinion, which makes it difficult to analyze. After all, who can say what might make someone happy or not? But we could still analyze it a bit. For example, has the politician said anything in the past that suggests they wouldn’t want to provide a list? Are they contradicting themselves now? If you support the politician, then it can be difficult and uncomfortable to ask yourself that question and to analyze the statement dispassionately. After all, nobody wants to discover that someone they support has been inconsistent, or even that they might be lying. But that’s what critical thinking is all about: deliberately setting aside your biases and discomfort, and focusing on what is objectively true.

The second statement might be easier to prove or disprove. Other media accounts or records might well indicate that the government did indeed ask the politician for a list of candidates. If so, that means the politician is simply lying. It can be extremely uncomfortable to confront the fact that someone you support is lying, but critical thinking demands it.

Confronted with that reality, many non-critical thinkers who supported the politician might start trying to create new “facts” to justify the erroneous statement. “Oh, the administration didn’t ask in writing,” they might offer, or, “The administration didn’t ask politely.” That’s an attempt to preserve something as fact which is not fact, simply so the politician’s supporters can save face. Critical thinkers avoid that behavior. Instead, if a critical thinker is wrong, and can be proven by facts to be wrong, then they simply accept it and move on.

I used a political example because most people get pretty passionate about politics; it’s an area where a lot of us (me included) let our emotions get in the way of critical thinking. But we can sometimes operate from our emotions at the workplace, too! Whether it’s a discussion of the “best” operating system for a particular application, or the “best” programming language for a new application, or the “best” way to engineer the network, we can all let our own biases color our statements and decisions. Critical thinking requires us to drop whatever stake we might have in the discussion, and to drop whatever outcomes we might fear. Instead, we have to focus on facts, and facts alone.

Now, let’s look at a second example: imagine that you’re at work, and you’re asked to design a new user interface for an application that the company has created. One of the many choices you’ll have to make might include deciding on a “dark theme” or a “light theme” for the user interface. Someone on your team says, “We should use a dark theme, because that’s what everyone likes nowadays.”

Do you have any facts to support that statement? Or is that statement really a theory, which needs proving or disproving? If you accept the statement as a theory, then you could conduct interviews, surveys, and other types of research to prove or disprove the theory, and then proceed with whatever new facts you uncover.

Being a critical thinker, if done improperly and without empathy, can make you unpopular. Nobody wants to work with someone who just uses facts as a blunt weapon to make other people feel bad or look bad! Here are some tips to being a successful critical thinker without offending your colleagues:

-

Critical thinking should never be used to help you “win” a discussion. It should be a way for the team to win.

-

You need to be a consistently critical thinker. This isn’t a behavior you should “turn on” when it benefits you, and “turn off” when it does not.

-

Consider the feelings and experiences of the other human beings in the discussion. Don’t just snap, “Where are your facts?” at someone. Instead, try to guide the conversation with respect for everyone else’s humanity. “That’s a theory we can start with. What facts do we all have that could support that theory, or that might poke holes in it?”

-

Sometimes, there is no objectively correct answer. A good critical thinker will recognize that: “Look, either of these programming languages would get the job done. We’re split about 50/50 on which to use, and we recognize that half the team will have some learning ahead of them no matter which way we go. This doesn’t appear to be a matter for facts and data at this point—just opinion. How do we want to just pick one and move forward?”

-

Recognize when tightly held opinions, versus facts, may be driving a conversation. Also recognize when someone on the team may need a face-saving way to move away from the world of belief and into the world of critical thinking. When you can, be the one to help them do so, rather than beating them up about it. For example, you might try to restate their belief as a theory: “You know, that’s an interesting idea. We can certainly do some research to prove or disprove that.”

-

Look for the biases in what you read and hear. We all have biases; it’s a natural part of being human. But when someone else is pushing an argument using their biases, try to recognize those, and decide if the bias is pushing a conversation or decision in a particular direction, without being backed by data. It can also sometimes be helpful for the group to acknowledge bias when it comes up: “You know, there’s a possibility that’s just our experience, and we probably should be careful about assuming our experience is universal.” That helps put a bias front and center, and lets everyone acknowledge it and work to avoid it.

I’ll offer you an example, from a fictitious news article on beef.

Such an article can be compelling, but it exhibits some biases and is not entirely data-driven. Consider:

-

The 20% figure from Beef Magazine is accurate (https://www.beefmagazine .com/mag/beef_evolving_industry), but my article plays loose with the facts. The actual Beef Magazine article also states that cattle herds decreased in size beginning in the 1970s.

-

The 5% number is not cited, which is suspicious. Alleging that you are presenting hard data and not citing the source of the data it is an indicator that bias my be present.

-

The cholesterol numbers are cited, but red meat consumption is not the only driver of cholesterol gains. There are other contributors, including other dietary items, a sedentary lifestyle, and genetic factors.

-

The article’s conclusion reveals its bias. Moving to an entirely plant-based diet would also require the elimination of other animal products, such as pork, seafood, and poultry, none of which were previously mentioned in the article. It is unlikely that eliminating meat would create a reversal of climate change, even if you accept the article’s uncited 5% figure. At most, the article has created a vague argument for consuming less beef.

Every day, we’re confronted with messages designed to make us change our actions or change our minds. Many of those messages are based on bias, not on data. In your personal life, of course, you’re free to follow your opinions and beliefs. In business, however, we should all strive to set aside our opinions and beliefs, and instead operate from a set of objective data. Being a critical thinker means being able to identify when bias is taking precedence over data, and to help push back toward a data-driven conversation.

15.3 Be data-driven

Ideally, every decision a business makes would be based upon data. That isn’t always possible, though, because sometimes the necessary data simply doesn’t yet exist, and you don’t have the time or resources to create it. In those cases, good businesses will tend to rely on the experiences of their leaders, leaning on the past to help navigate the future. That’s fine, too, but whenever possible you want to drive decisions based on data. Data that’s objective, not subjective; that is verified, correct, and meaningful.

“Windows is better than Linux.” “Java is better than C#.” “Cisco is better than Juniper.” These are all statements I’ve heard in meetings where a company’s critical long-term technology decisions are being made—and none of them are based in fact. In my role as a consultant in those meetings, I try to tease out what facts exist.

For example, “Windows is better than Linux for us, because we have dozens of people who already understand Windows. Windows can run the Apache web server just fine, which is what our application really hinges on. We already have an enterprise agreement for support of Windows, whereas our four Linux machines don’t have a formal support agreement in place.” Okay—those are some facts, and they help lend context and meaning to the original statement that “Windows is better than Linux.” We have some data points we can examine, verify, and base a decision upon.

“If we adopt this new source control system, we’ll save time.” That sounds like a theory or an opinion, or maybe even a belief; it doesn’t sound like fact.

“Our current source control system burns about 4 hours a week, per developer, in overhead time while we work through code merge conflicts. Each developer is paid $84 an hour in fully loaded salary, which amounts to about $336 per week or $17,472 per year. Across all ten developers, that’s $174,720 per year in wasted time. The proposed system automates that merge process, and other users of that system said it cuts down their overhead by 50%. So we would be looking at a one-year savings of $87,360, which far outweighs the cost of migrating and implementing the system. My opinion is that we should do a trial to verify the 50% number for our environment.”

That was a data-driven set of statements. Even though one piece of data that was external and unverified, we’ve suggested a data-driven way forward that involves testing that 50% number and verifying it for ourselves. The payroll numbers are facts, and they’re ones anyone in the company could have verified through the Payroll department. The 4-hours-per-week number could also, one presumes, be verified—perhaps by conducting a pilot project measuring labor hours more rigorously than usual. These statements have moved beyond the realm of belief: the person making the statement has stated some facts, concluded with an implied theory, and proposed that the theory be put to the test in a pilot project. That’s the way to do it!

15.4 Beware the data

Mark Twain popularized a cautionary phrase: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” In other words, data can be used as much for us as against us. Statistics—one common form of data that businesses rely on—can often be stated in whatever way someone requires in order to support their opinion.

For example, suppose you’re sitting in a product development meeting, and someone says, “We need to rearrange the home screen, because we have data showing that users find it confusing.” They might then share a quick graph that they derived from a recent customer research project, showing that most customers do indeed find the home screen confusing. That’s pretty compelling data—but it’s still worth looking into.

Suppose their research was based on a survey, and the survey question was, “Do you find the home screen extremely confusing and difficult to use?” Now suppose that they surveyed just ten people. That’s not very solid data: the question is written in a way that could lead someone to answer “yes” without thinking about it, and the number of people surveyed probably isn’t statistically significant. A critical thinker who dug into the “customer research” might point out those shortcomings, and suggest a round of more thorough research to arrive at a stronger set of data.

Data does not collect itself. It is collected by people, or by computers that have been programmed by people. All people have biases; therefore, all data can also be biased. For example, suppose you work on a software application that has built-in mechanisms for reporting on user behavior. The collected data helps you analyze which features are used the most, amongst other details. However, you discover that—perhaps for legal reasons—your data-collection code isn’t used for copies of the application deployed in the Asia region of the world. Your data is now untrustworthy, because it does not reflect the full reality of the world. The “bias” in the data may be unintentional and unavoidable, but it is a bias nonetheless.

So while it’s important to be a critical thinker, and important to be data-driven, it’s also important to be critical of the data. Make sure you understand where your data comes from, and what biases might be present in it, and how you might control for those biases before you rely on the data to drive your thinking.

15.5 Further reading

-

Critical Thinking Exercises, http://mng.bz/y9AG

-

Master Your Mind: Critical-Thinking Exercises and Activities to Boost Brain Power and Think Smarter, Marcel Danesi (Rockridge Press, 2020)

15.6 Action items

For this chapter, I want to offer a couple of exercises to help you focus on critical thinking:

-

Visit Thoughtco’s Critical Thinking Exercises (http://mng.bz/y9AG) for a good, fundamental critical thinking exercise. The exercise explores the importance aspects of critical thinking through an amusing example, helping you more easily separate beliefs and biases from objective fact.

-

81 Fresh & Fun Critical-Thinking Activities, by Laurie Rozakis (http://mng.bz/ Mg77), is a free, downloadable book with a number of thinking activities. It’s designed for kids, and I recommend you go through some of these exercises with your own kids (and if you don’t have kids, perhaps ask a family member if you can “borrow” one of theirs). Watching a child go through these exercises can reveal a lot about the thinking patterns we fall into as adults, and help you take a fresh look at your own thinking.