THE FIRST REALLY, REALLY

HARD GOOD-BYE

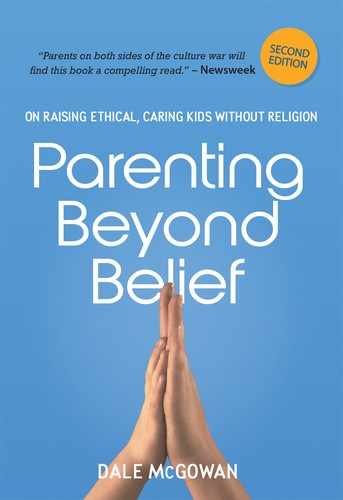

DALE McGOWAN

“Daddy! Something’s wrong with Max!” Erin (10) was upset, her face a mask of anguish. “He’s making sounds I’ve never heard before . . . and he’s laying wrong!”

Her guinea pig Max, the first pet that was all her own, was clearly not okay. The vet confirmed an upper respiratory infection the next morning, dispensing a little medicine and not much hope.

“Guinea pigs are prey items,” he said, introducing me to a colorful new term I was glad Erin didn’t hear. “They don’t handle stress well. But sometimes the medicine works. He’ll either get better quickly . . . or he won’t.”

Erin held him all evening, cooing and stroking and sobbing. In the morning, he was gone.

When Erin’s heart breaks, it takes every other heart in the room with it—and her heart was as broken then as I’d ever seen it.

I know the loss of Max was an important experience for her. Pets can contribute, however unwillingly, to our lifelong education in mortality. Though we don’t buy pets in order for kids to experience death (with the possible exception of aquariums, oh my word), most every pet short of a giant land tortoise will predecease its owner.

The deaths of my own various guinea pigs, dogs, fish, and rabbits were my first introductions to irretrievable loss. At their passings, I learned two things Erin learned with Max: how to grieve and just how deeply we can love. They certainly helped prepare me for the sudden loss of my father. It didn’t shorten my grief, which continues to this day. But the grief didn’t blindside me in quite the way it would have if my father’s death had been my first experience of profound loss.

When we looked into the cage Thursday morning and saw that Max was still, Erin screamed, then did the precise opposite of what I would have done: She flung open the cage, grabbed him, hugged him to her, and wailed.

I’ve never had that kind of equanimity with the dead. I recoil from lifelessness. When my dog Opie died, I was in my late thirties and still seriously considered paying someone $300 to remove his body from the yard. When (for lack of $300, and no other reason) I did it myself, it took all of my personal steel. Ever since I stared at my dead father, I just can’t bear the recognition of what’s no longer there. But Erin sprints toward it, even in abject grief.

She hugged Max’s little body to her for an hour and keened. She stroked his fur and touched his teeth and gently rolled his tiny paws between her fingers, all the time whispering, “Maxie, Maxie. Please wake up.”

Then came a monologue both stunning and familiar—that ancient litany of regret, guilt, and helplessness:

“I wish I had given him a funner life. He didn’t have enough fun.”

“Do you think he knew I loved him?”

“I should have played with him more.”

“I wanted to watch him grow up!”

“Do you think I did something wrong? I must have done something wrong!”

“I want to hear his little noises again.”

“It isn’t fair at all. It isn’t fair. Things should be fair.”

She sang in a concert at the end of the day and was all smiles for two full hours—then lost it again when we returned home. So it was for two days.

We buried Max in the backyard under a metaphor of falling yellow leaves. Erin placed him in the shoebox on a layer of soft bedding. She put his water bottle to his lips once, twice, three times, convulsing with tears. She added food pellets near his head, like an ancient Egyptian preparing a pharaoh for the journey to the next life. Flower petals, followed by Max’s favorite toy, and at last—this nearly did me in—Erin carefully dried her tears and placed the tissue in with him.

We talked over the grave about what a lucky guy he’d been to be born at all, that a trillion other guinea pigs never got the chance to exist, to be loved and cuddled like he was. She liked that.

Experiencing loss and regret has one undeniable payoff: It can make us appreciate what we still have. And our dog Gowser was lavished with more love and attention in the following days than ever before.

A year later almost to the day, her sister, Delaney (7), got a guinea pig of her own. Erin asked to go with us to the pet store to help Laney pick out the toys, the food, the bedding. She knowledgeably led her sister up and down the aisles. “Max really liked timothy hay,” she said. “You’ll want to get some of that. Ooh, and look, there’s that little wooden thing he liked to chew on!”

As we stood in line at the register, Erin looked up at me. “I’m surprised I’m so okay with all this,” she said. “I mean, I still miss him a lot, but it’s not so, . . . you know . . .” She pressed a palm to her chest and closed her eyes, then looked up again. “You know?”

I knew. I reminded her of something she said a few days after he died. “You thought it would never stop hurting, remember?”

She nodded. “But it did. Time is amazing.”

And there it is. In addition to learning how much she could love and how much she could grieve, she learned that no matter how much a loss hurts, it will eventually hurt less. So next time—and there is always a next time—she’ll have a comfort she didn’t have before.

![]()