Preface

The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.

Bertrand Russell

I remember clearly the first vegetarian I ever knew, a friend from college named Kari. She had given up what I considered one of the great joys of life. Kari could look forward to no seared orange duck, no filet mignon in mustard-caper sauce, no southern fried chicken, for the rest of her days. I just didn’t get it. This stuff is delicious, after all. Maybe she just hasn’t had a really good steak, I reasoned to myself. That had to be it.

One day I interrupted her morning carrot break in mid-crunch to ask Kari what on earth she could possibly be thinking.

She assured me she’d had a good steak—quite a few, in fact. And pork chops had been a favorite since childhood. She loved the taste of meat. But she had looked into the issues around the consumption of meat—far more deeply than I ever had—deciding at last that the negatives clearly outweighed the positives. Eating meat is incredibly unhealthy, she said, not just marginally so, and involves unspeakable cruelty to our fellow creatures. She didn’t want to be a part of that, so she stopped eating meat.

We lost touch after college, but if Kari has kids, I’ll bet she has raised them according to those values, since she would want the best for them. But knowing her, I’m also sure she’d want them to come to vegetarianism as their own life stance only if they reasoned it out and adopted it as their own value—not because she forced it on them. They would know their mother’s strong feelings and the reasons behind them, then decide for themselves once they were old enough if it was right for them.

I have a lot of respect for that kind of parenting.

Now I’m raising kids of my own, trying hard to give them the best of my experience and values. I’m not a vegetarian, though I’ve considered that a character flaw of mine ever since Kari. But there’s another area about which I’ve developed some heartfelt opinions: religious belief and practice.

Just as Kari had plenty of good steaks, I had a lot of positive experience with religious people and institutions. I’ve known many wonderful religious people and have found much that is compelling and comforting in religious teachings.

I developed a particular interest in “the big questions” at the age of 13 when my dad died. My grief was tempered by a consuming curiosity about death, from which tumbled a thousand questions about life. I began a serious engagement with religious questions, attending churches in nine denominations, reading the scriptures of my own culture and others, asking questions of ministers, priests, theologians, and lay believers, and reading carefully the arguments for and against religious belief—coming at last to the strong conclusion that religious claims are human-created fictions.

Religious friends are often baffled. This stuff is delicious, they say. Afterlife rewards, unconditional love, ultimate meaning … I agreed—they are yummy. But I’d come to the further conviction that religious belief, for all its benefits and consolations, also does real harm to us, individually and collectively. The negatives far outweighed the positives for me, so despite all its comforts and consolations, I set religion aside.

I’m not indifferent to theological questions, any more than Kari’s vegetarianism meant she was indifferent to questions of diet and animal welfare. I am fascinated by religious questions, as are most secularists, and take them very seriously. Kari’s position resulted from the seriousness of her interest; she believed vegetarianism was the right choice, even believed that I too should adopt it, though she wasn’t about to force it on me or anyone else. That’s why I’ll bet even her kids would ultimately have a choice.

The same is true of my parenting regarding religion: I really do believe I’ve made the best moral and intellectual choice in setting religion aside. I think the negatives of religious belief outweigh the positives, but I would never want to see someone forced to believe as I do. That includes my children. They deserve an honest chance to work things out for themselves. The process, not a given outcome, is the thing.

Which brings us at last to our topic.

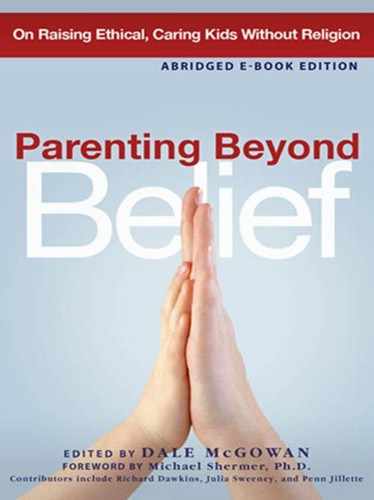

Parenting Beyond Belief is a book for loving and thoughtful parents who wish to raise their children without religion. Not that this is the only “right” way to parent; it would be just as silly to imply that one cannot raise good, intelligent, moral, and loving children in a religious home as to imply the opposite. There are scores of books on religious parenting. Now there’s one for the rest of us.

Religion has much to offer parents: an established community, a predefined set of values, a common lexicon and symbology, rites of passage, a means of engendering wonder, comforting answers to the big questions, and consoling explanations to ease experiences of hardship and loss. But for most secularists, these benefits come at too high a price. Many feel that intellectual integrity is compromised, the word “values” too often turned on its head, an us-versus-them mentality too often reinforced. Religious answers are found unconvincing yet are held unquestionable. And so, in seeking the best for our children, we try to chart a path around the church—and end up doing so without a compass.

Parenting Beyond Belief demonstrates the many ways in which the undeniable benefits of religion can be had without the detriments. Just as vegetarians must find other sources of certain vitamins, minerals, and proteins, secular parents must find other ways to articulate values, celebrate rites of passage, find consolation, and make meaning. Fortunately, just as the vegetarians have beans, fortified grains, and soy milk to supply what they need, secular parents have Parenting Beyond Belief.

So welcome, then, to a parenting book for theological vegetarians.

Approach and Focus

This is not a comprehensive parenting book. It’ll be of little help in addressing diaper rash, aggression, or tattling. It is intended as a resource of opinions, insights, and experiences related to a single issue—raising children without religion—and the many issues that relate directly to it.

You may also note a relative lack of prescriptive instruction. Although our contributors include MDs, PhDs, and even two Reverend Doctors, there’s little attempt to dictate authoritative answers. Our writers suggest, inform, challenge, and encourage without ever claiming there’s only one right way. (Unlike a childcare guide I can see on my shelf right now, with the subtitle The Complete and Authoritative Guide. Holy Moses!) And a good thing, too—secularists are a famously freethinking bunch. It’s the attribute that ended us up secularists, after all—that desire to consider all points of view and make up our own minds.

This is also not a book of arguments against religious belief, nor one intended to convince readers to raise their children secularly. This book is intended to support and encourage those who, having already decided to raise their children without religion, are in search of that support and encouragement.

There are many outstanding resources for adults wishing to consider the arguments in support of and in opposition to religious belief itself. And that’s important work: Intellectual and ethical maturity can be measured in part by a person’s willingness to engage in constant reflection on what he or she holds to be true and good. Parents in particular must be able to articulate the foundations of their own values and beliefs at a moment’s notice—and what better describes the appearance and disappearance of opportunities in parenting than “a moment’s notice”? Ungrounded, unexamined beliefs, whether secular or sacred, are the most inflexible, the least open to reconsideration and revision. In order to raise children whose convictions are grounded in reflection and an openness to change, we must model the same.

You may encounter some new terminology, including labels for the various categories of disbelief and ideas from philosophy. Each such word is defined in a glossary at the end of the book.

![]()

Parenting is already among the toughest of jobs. Living secularly in a religious world is among the most difficult social choices. When these challenges are combined, and a parent wishes to raise children without religious influences, the difficulties are compounded. But despite the difficulties, a large and growing number of parents are rising to the task. In 1990, 8 percent of respondents to a USA Today poll identified themselves as nonreligious. By 2002 that sector had grown to 14.1 percent.1 The U.S. Census of the year 2000 counted 37.3 million households in the United States with school-age children. These numbers yield a conservative estimate of 7 million individual nonreligious parents in the United States today. Another of the purposes of this book is the clear establishment of that simple fact. It’s easy to assume that every parent on your block, everyone cheering in the stands at the soccer game or walking the aisles of the supermarket, is a churchgoing believer. It’s the assumed default in our culture. But it isn’t true. All you need is to realize that they are making the same assumption about you. You are not remotely alone.

A good illustration of the presence of closeted disbelief is brought home to me whenever I attend book club discussions of a novel of mine. The main character is a secular humanist and the themes center on belief and disbelief, so discussion always turns to the beliefs of the club members. At some point, someone will say something like, “You know what? I never had the name for it before, but I guess I’m a secular humanist, too.” A ripple of surprise goes around the group—not judgment, not condemnation, just genuine wonder as the members realize how much we all assume incorrectly about those we think we know well. “Me too,” someone else will say, followed usually by a third and fourth. Twenty, 30, even 50 percent of a given group always turns out to be nonbelievers, all of whom had assumed they were alone in their disbelief. There is real elation in overturning false assumptions, accompanied by a deep enrichment of relationships after this diversity of belief is unpacked.

The same is true among secular parents: We are present, but not remotely accounted for. The proliferation of secular parenting discussion forums and freethought family organizations attests to the growing interest and need for a book that brings the many issues around secular parenting into focus. Such a book can also help to counter the stigma and ignorance surrounding religious disbelief by simply illustrating what is already going on quietly all around us: the raising of healthy, happy, ethical children in the absence of religious ideology.

It was during my tenure as editor of the Family Issues page of the Atheist Alliance website that I first became aware of the scarcity of resources for secular parents. A brief flirt with the idea of writing a book myself was fortunately cast aside in favor of the current format: a collection of essays by many writers, each bringing a different perspective and set of experiences to the task. In the pages that follow, you will read Dr. Jean Mercer on moral development; comedian Julia Sweeney on her uncertain and often hilarious grapplings with the religious influences swirling around her adopted daughter; Richard Dawkins’ open letter to his daughter; illusionist and debunker Penn Jillette on being a new secular father; Dr. Gareth Matthews on talking to children about evil; Donald B. Ardell on secular meaning and purpose; legendary bluegrass musician Pete Wernick on the “mixed marriage”; Tom Flynn and yours truly facing off on the Santa Claus question; excerpts from the writings of Mark Twain, Bertrand Russell, and Margaret Knight; and essays by over twenty other physicians, educators, authors, psychologists, and everyday secular parents, plus recommended resources for further investigation of this boundless topic.

One thread runs throughout this book: Encourage a child to think well, then trust her to do so. Removing religion by no means guarantees kids will think independently and well. Consider religion itself: Kids growing up in a secular home are at the same risk of making uninformed decisions about religion as are those in deeply religious homes. In order to really think for themselves about religion, kids must learn as much as possible about religion as a human cultural expression while being kept free of the sickening idea that they will be rewarded in heaven or punished in hell based on what they decide—a bit of intellectual terrorism we should never inflict on our kids, nor on each other. They must also learn what has been said and thought in opposition to religious ideas. If my kids think independently and well, then end up coming to conclusions different from my own—well, I’d have to consider the possibility that I’ve gotten it all wrong, then. Either way, in order to own and be nourished by their convictions, kids must ultimately come to them independently. Part of our wonderfully complex job as parents is to facilitate that process without controlling it.

As editor, I’ve encouraged these outstanding authors to retain their individual styles and approaches, even to articulate contrasting opinions on a given question, confident that you as a secular parent can handle the variety and would want nothing less. This is “big tent secularism,” offering many different, even contradictory perspectives on living without religion. What other book would include two ministers and Penn Jillette? The authors’ approaches are at turns soberly academic, hilariously off-the-cuff, inspiring, irreverent, angry, joyful, confident, confused, revealing, and empowering. Skip around, dip and dive, and be sure to challenge your natural inclinations. If the reverends make you feel most comfortable, you should read Dawkins, Tanquist, Barker, and Jillette—there’s an incredible amount of insight there. And if the religious impulse seems like a completely alien thing to you, read Gibbons, Matthews, and Nelson for an equal dose of wisdom. There are countless ways to be a nonbeliever and no need to fit everyone into a single skin.

Note also that all editorial material—chapter introductions, book reviews, preface, and my own essays—represents just one perspective on these questions.

It happens to be the most brilliant and accurate perspective, but it is only one, and my fellow contributors should not be assumed to agree with everything that surrounds their own contributions.

I hope you find this a worthwhile contribution to the bookshelf for those of us taking on the wonderful and humbling task of raising the next generation of people inspired by love and guided by knowledge.

Dale McGowan, Ph.D.

Endnotes

1. Cathy Grossman, “Charting the unchurched in America,” USA Today 3/7/02: www.usatoday.com/life/dcovthu.htm