Practical Observations on Dialogue

Coming as they do from different disciplines, the theorists discussed above offer remarkably similar ideas about dialogue. Although some include ideas that the others do not, and there are clear differences among them, none basically contradicts the others.

The observations that I offer in this section are, in one sense, a summary of these theorists; in another sense, they represent my own view of dialogue, which has been informed by these thinkers but which is not limited to their ideas.

In my view, dialogue is talk—a special kind of talk—that affirms the person-to-person relationship between discussants and which acknowledges their collective right and intellectual capacity to make sense of the world. Therefore, it is not talk that is “one way,” such as a sales pitch, a directive, or a lecture; rather it involves mutuality and jointness. I do not want to suggest that dialogue is without emotion and passion or that it is without confrontation and challenge. It involves both, but within bounds that affirm the legitimacy of others’ perspectives.

Dialogue has the potential to alter the meaning each individual holds and, by so doing, is capable of transforming the group, organization, and society. The relationship between the individual and the collective is reciprocal and is mediated through talk. People are both recipients of tacit assumptions and the creators of them. In this way dialogue results in the co-creation of meaning. The meaning that is created is shared across group members; a common understanding is developed. I am hesitant here to use the familiar word consensus, because it seems too restricted, limited to a decision-making process. I mean something more encompassing. The common understanding engendered by dialogue is one in which each individual has internalized the perspectives of the others and thus is enriched by a sense of the whole. Dialogue brings people to a new way of perceiving an issue that may be of concern to all. That new understanding might include what actions (decisions) should be taken individually and collectively, but such resulting actions are not its essence; its essence is that people have collectively constructed new meaning.

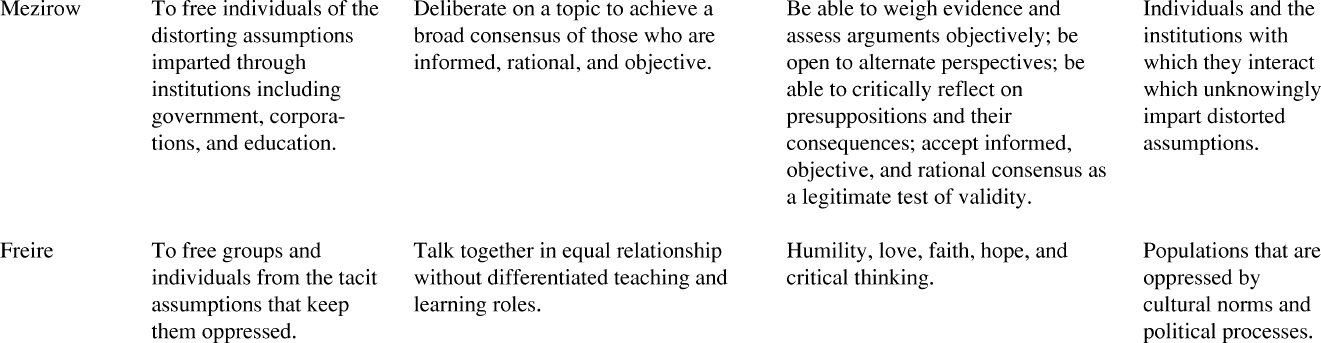

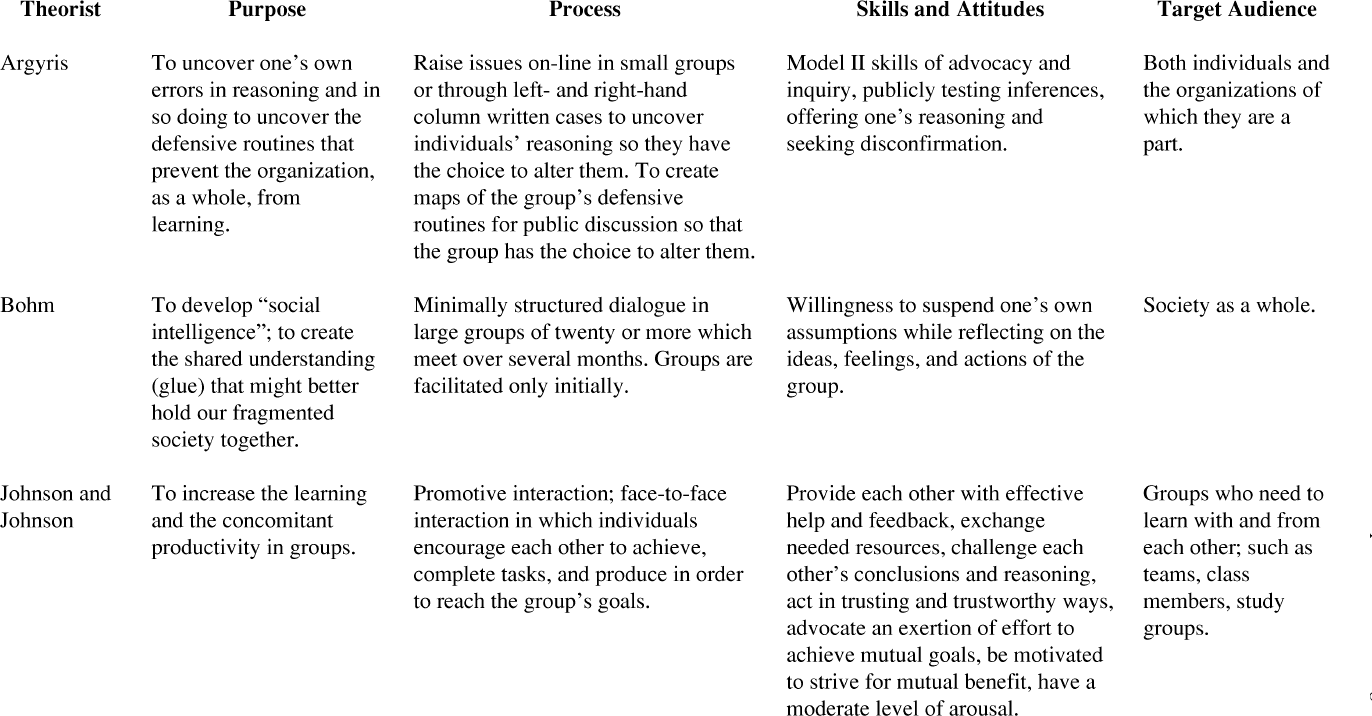

It is worthwhile to consider what purpose dialogue can serve (see Table 1). Argyris has defined the goal as uncovering one’s own and the organization’s unintentional errors that limit learning. Mezirow’s goal has been emancipating individuals from the untested assumptions that limit their development as human beings. Johnson and Johnson took as their goal learning and productivity. The goal Bohm had in mind was shared meaning, which he believed people can come to by dissolving the programs that blind them. Finally, Freire’s goal has been to transform the world through understanding and re-creating it. In all of these perspectives there is the intent to uncover that which is tacit—to become aware of the paradigm in which those individuals engaged in the dialogue are themselves embedded. By making manifest that which has been taken for granted, the participants in the dialogue are able to hold their assumptions up for examination and, when warranted, to construct new joint meaning that is tested against their reasoning.

The Role of Others in Learning

Dialogue occurs in a group setting. The group may be quite small, as in some of Argyris’ and perhaps Johnson and Johnson’s groups, but it is clear that Bohm and Freire were talking about larger groups, even forty or more. People often mistakenly think the prefix dia means “two” and thus think of a dialogue as only occurring between two people. But in its Greek origin dia means “passing through,” as in diathermy, or “thoroughly” or “completely,” as in diagnosis. Thus, dialogue is a social event, a community of people thinking together.

As each of these theorists has suggested, people need others to see what they cannot see for themselves. That is a difficult idea in a society steeped in individualism. To acknowledge that others are needed is the act of humility that Freire talked about or the acceptance of our vulnerability that Bohm referenced. People seem more comfortable with the idea that others can provide them with new information than with the idea that they need others to put their own thinking to a test. Stephen Brookfield (1988) has said, “Trying to understand the motive for our actions or attempting to identify the assumptions undergirding our apparently objective, rational beliefs is like trying to catch our psychological tail.… We must hold our behavior up for scrutiny by others, and in their interpretation of our actions we are given a reflection, a mirroring of our own actions from an unfamiliar psychological vantage point.”

People Already Know How to Have a Dialogue

Dialogue needn’t be thought of as something unfamiliar or new. People already have the necessary skills. For example, most people can think of someone with whom they engage in a certain kind of conversation on a fairly consistent basis—perhaps a long-time colleague, a cherished friend, or a spouse. These are conversations in which each person works hard to grasp the perspective of the other, sensing that he or she is not being judgmental but rather trying to see the world through the other’s eyes; each person has his or her thinking seriously challenged and seriously supported. This is dialogue, and although it may not always feel comfortable nor be satisfying in the moment, it is authentic in a way most work conversations are not. If people value such talk, it is in part because they value the individual with whom it takes place and recognize the value that that person places on them. People value the content of the dialogue as well, recognizing that they have grown and changed through it.

If one accepts this hypothesis, that people are capable of engaging in a dialogue without necessarily having to learn new skills or technique, then dialogue is more about the nature of the relationship between people than about the specific words they say or the technique they employ.

When people talk with others they convey not only a content message but also who the others are in relation to themselves—for instance, that the others are equal, less knowledgeable, revered, or unimportant. That relationship is conveyed through what is said and what is withheld, the choice of words, tone, and nonverbal actions. The relationship expressed through dialogue is one in which the other is valued, trusted, and an equal whose ideas are respected if not always agreed with. People are in a person-to-person relationship with the other.

Freire’s five requirements for dialogue cited above—humility, love, faith, hope, and critical thinking—are about the nature of the relationship between the speaker and those with whom the speaker is in dialogue. When Freire (1994, p. 71) said, “Self-sufficiency is incompatible with dialogue. Men and women who lack humility (or have lost it) cannot come to the people, cannot be their partners in naming the world,” he was talking about how people view themselves in relationship to others.

Even in Argyris’ more technical approach to dialogue, at the heart of Model II skills, there are the values of valid information, free and informed choice, and internal commitment to the choice. Argyris’ values speak to the nature of the relationship between people—that is, that the intent of the individual should not be to use others, either purposefully or unwittingly, but rather to guard free and informed choice for both him- or herself and others.

I am suggesting here that dialogue is not a difference in technique but a difference in relationship. I seriously question whether more technique is necessary. There is already a great deal of technique that relates to clear feedback, supportive and clarifying statements, air time, paraphrasing to check out what is understood, and so on. That is not to say that people consistently make use of the technique that is available to them. But even when they do, they may not change their intent to manipulate or control. People may have altered their words but not the nature of their relationship to others.

Dialogue transpires in the context of relationship, and central to it is the idea that through interaction people acknowledge the wholeness, not just the utility, of others.

Dialogue Can Offset the Instrumental Nature of Work Relationships

The relationship built into much of the talk at work is instrumental—that is, the person with whom one is talking is viewed as a means to accomplish an objective. The term human resource, used as a synonym for organizational members, symbolizes the instrumental nature of relationships in organizations. To speak of people as a resource is to relegate them to the status of objects, comparable to equipment or supplies. The use of the term makes it possible to deny that the resource, the persons involved, are human beings with purposes and wills of their own. Even the term employee carries with it an instrumental flavor.

When Bohm eschewed agendas it was an attempt to avoid the instrumental relationships that agendas typically precipitate. Instrumental relationships are subject-object relationships rather than person-to-person relationships. In Martin Buber’s (1970) words, “I-It” rather than an “I-Thou.”

That said, it is clear that hierarchical structures in organizations are designed as a way to get work done through others. A manager’s job, by definition, is instrumental and his or her relationship to subordinates is instrumental. If instrumental relationships are embedded in the way organizations are structured, is it not asking the impossible to encourage the holders of those positions to dialogue in a person-to-person relationship?

Perhaps what is necessary in organizations is to create opportunities to have frequent dialogue and through that dialogue to come to shared meaning. Then, with that co-created meaning as a foundation, individuals and groups could interact in more purposeful ways to make decisions and problem solve. I do not want to go so far as to say they would “engage in their normal way of interacting in business” because even when people interact in more purposeful ways than dialogue would support, it would be inconsistent to use others as instruments to accomplish a purpose without their full knowledge and uncoerced agreement with the purpose. In many organizations that caveat may not represent business as usual.

If there were frequent dialogue in our organizations, then the nature of people’s relationships with each other might change. As Bohm (1992, p. 119) said, “When you listen to somebody else, whether you like it or not, what they say becomes part of you.” Through dialogue it might be possible to alter taken-for-granted assumptions not only about what people are trying to accomplish together but also about how people structure their relationships. Putting collective intelligence to use, they might find some resolution to the management emphasis on instrumentality.

Dialogue Affirms the Intellectual Capability of Ordinary Human Beings

Dialogue is based on the principle that the human mind is capable of using logic and reason to understand the world, rather than having to rely on the interpretation of someone who claims authority through force, tradition, superior intellect, or divine right. The theorists considered here are not the only ones who have faith in the ability of human beings to comprehend their world. Such faith is at the heart of Reginald Revans’ (1980) action-learning process. It is also in the Theory Y that Douglas McGregor (1960) suggested as an alternative to Theory X. More recently it is in the ideology that underlies Marvin Weisbord’s (1992) advocacy of future search conferences (see Appendix A), as well as Merrelyn Emery’s (1989) similar “whole system in a room” processes. And, of course, it underlies participative democracy.

Dialogue is an affirmation of the intellectual capability of not only the individual but also the collective. It acknowledges that everyone is blind to his or her own tacit assumptions and needs the help of others to see them. It acknowledges that each person, no matter how smart or capable, sees the world from a perspective and that there are other legitimate perspectives that could inform that view. People know this intellectually and yet have great difficulty living its reality. I am often struck by the language I hear when managers talk about such concepts as empowerment, participation, or even dialogue: “We want others to feel involved,” not “We need the ideas of others”; “People will be more willing to change if they have had input into the change,” not “We need the ideas of others to understand how to make the change.” The emphasis in managers’ language is more often on the manipulation of the perception of others than on the need for or use of their collective intellect. Perhaps this language reflects ambivalence or perhaps it reflects a partial step toward the use of the collective intelligence.

The Outcome of Dialogue Is Unpredictable

It is not possible to anticipate the outcome of dialogue; if it were, there would be no need to engage in it. Because meaning is co-created in the act of dialogue, it cannot be known ahead of time what meaning will emerge. It is possible that some taken-for-granted assumptions may be raised that management would prefer be left alone—for example the differential in salary between upper management and workers, the organization’s effect on the environment, or the overall purpose of the organization.

It would, however, be inconsistent to say to a group in dialogue: “Examine the paradigms under which you function so that those that are limiting can be altered, but do not examine anything that touches on issues of power or control.” If a forum is created in which dialogue can occur, it must be accepted that some of the beliefs that people hold sacred will be challenged.

The unpredictability of dialogue may be problematic in yet another sense. That is, when resources are allocated for an organizational effort such as dialogue, people typically want some assurance up front about what outcomes might be expected. To do less would not be seen as exercising fiscal responsibility. Yet no one can anticipate where dialogue might go.

The practice of dialogue depends upon the organization having a climate which is open and respectful of individuals and where information is shared, members are free from coercion, and everyone has equal opportunity to challenge the ideas of others. Without such a climate it is unlikely that either individuals or groups would expend the energy or incur the risks that would be needed for dialogue to take place. For example, it is unlikely that individuals would hold their opinions up for scrutiny in a climate where mistakes are seen as failure and the norm is to cover up what went wrong. It is equally unlikely that organizational members would challenge others if that challenge might be viewed as insubordination.

Thus a paradox exists: In order for organizational members to risk engaging in dialogue, the organization must have a climate that supports the development of individuals as well as the development of the organization; yet that climate is unlikely to come into being until individuals are able to engage in dialogue. The individual and the norms of the system are so intertwined that attempts to change either without changing the other are not likely to succeed. To the extent that either individual actions or system norms are tacit the change becomes even more difficult.

That said, the only place such a change can begin is with individuals—not the individual in isolation but individuals in community. When a group of individuals begins to change, even a nonsanctioned group, the organization has begun to change. Perhaps the first step in moving beyond the paradox is to name it—that is, to publicly identify the situation in which organizations find themselves, to raise it to the level of public discussion, of dialogue.