6

A Drop of Vinegar:

Solutions for Infectious Diseases

On the surface, David was no match for Goliath. Just a small boy in a tunic, armed only with a slingshot, yet this small boy killed a giant of a man. And so it is with infectious diseases. Minute microbes one cannot even see with the naked eye are able to kill beings much, much larger and, seemingly, more powerful than themselves—human beings like us.

Most often, however, the people they kill are poor and living in developing countries—like the Angolan soldier who contracts HIV and gives it to his wife before he dies of AIDS. Or like the baby from Zimbabwe who is bitten by a mosquito that transmits a parasite that causes a fever, then a seizure, before killing her of malaria. Or like the Indian schoolteacher who contracts HPV (human papillomavirus) on her cervix, which turns into cancer and spreads throughout her body before consuming her life. Despite the tremendous advances that have been made in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, people in developing countries like Angola, Zimbabwe, and India continue to fall like Goliath.

But it doesn’t have to be so. We have inexpensive solutions to control infectious diseases.

A Drop of Vinegar Can Save a Life

Over half a million women each year are diagnosed with cervical cancer and more than 225,000 die of this disease. Developing countries bear the majority of the global burden.1 Fortunately, there are new, simple, and inexpensive ways to diagnose and treat abnormal cells during the precancerous stage, killing the disease before it kills the woman. All it takes is a few drops of vinegar placed on the cervix, a cold probe, and the steady hand of a trained provider.2 The need is huge. And the remedies are easy and cheap.

So why are women in developing countries still dying of cervical cancer?

That’s exactly what Dr. Groesbeck Parham, an American gynecologic oncologist, thought when a colleague asked him to consider relocating to Africa to work. It seemed like the logical next step in his career, given his interests and passions. He had dedicated his career to providing care to some of the poorest people in the U.S.—first at Charles Drew University in south Los Angeles and later at institutions in Little Rock and Birmingham. Poverty does not end at the U.S. border, however; it widens and turns south.

So when the request came, he packed up his bags and left.

Despite the tremendous need, however, Dr. Parham found little opportunity to save women from cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Women arrived at his clinic too late. Even for those who arrived before their cancer had spread, the health system he found lacked sufficient pathologists, surgeons, cancer drugs, and radiation therapy to save them, and did not even have basic pain medications to relieve their suffering as their disease progressed. Most died at home, comforted only with the love of family and the certainty that their suffering would soon end.

While there were few good opportunities in Africa for cancer specialists, there were ample opportunities for AIDS experts. By 2005, money for AIDS was beginning to pour into Africa through the Global Fund to Combat HIV, Malaria and Tuberculosis (Global Fund), and the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Clinical and technical professionals who were expert in HIV clinical care, prevention, program development, research design, monitoring, and evaluation—anything AIDS related—were being actively recruited. That prompted Dr. Parham’s colleague Dr. Jeffrey Stringer, an HIV specialist from the University of Alabama, to move to Zambia and help start the Centre for Infectious Disease Research, Zambia (CIDRZ).

Cervical Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment in Developing Countries

Cervical cancer is caused by a sexually transmitted virus, the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is so common that most sexually active women get it at some point in their lives.3 Women with weakened immune systems, such as those who have HIV, have a harder time getting rid of HPV. In fact, women with HIV are four to five times more likely to contract cervical cancer. Unfortunately, most women in developing countries generally do not have access to Pap smears, the laboratory test that has helped significantly diminish cervical cancer deaths in developed countries.4

HPV can lead to abnormal cells on the cervix, which, if untreated, can become cancerous and lead to a slow, painful death. Fortunately, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) can diagnose cancerous and precancerous growths, and it is elegantly simple to do. During a pelvic exam, a trained nurse, or another nonphysician health care provider, washes the cervix with a small amount of household vinegar (acetic acid). Changes associated with precancerous and some cancer growths will appear as white lesions, and the vast majority can be treated on the spot with a cold match probe.5

Dr. Parham and his colleagues eventually received a small grant to study the rate of HPV infection among Zambian women with AIDS.6 Until that point, most studies had identified rates of precancerous cervical lesion at between 20 and 25 percent of the sample. However, among HIV-positive Zambian women, Dr. Parham found that almost all (94 percent) had precancerous lesions.7 This shocking finding drew international attention and prompted the Centers for Disease Control to fund a pilot cervical cancer prevention and treatment program in Zambia for women with HIV. This program was the world’s first cervical cancer prevention program linked to HIV care and treatment and has become a model program, training providers throughout Africa.8

The first task at hand for Dr. Parham was to figure out how he and Dr. Mwanahamhuntu, the clinic’s only other doctor, could see all the patients who needed their care. The only feasible way was to train nurses to do it and to supervise them well. This had been done with HIV treatment, and it had worked.9 Initially, quality control was easy since the screening clinics were nearby. However, as they began to place more nurses in clinics around the country, they had to come up with a better way.

![]() Task Shifting

Task Shifting

The answer came in a conversation with a colleague from PATH, a large Seattle-based NGO. PATH does health care innovation in seventy countries, and it was trying to solve a similar problem in China. The solution was for nurses to take a digital photograph of the cervix after the vinegar was placed on it. Dr. Parham later connected the camera to a computer that allowed the photograph to be immediately magnified to twenty times its actual size, allowing both the nurse and the patient to clearly see any lesion prior to treatment.10

![]() Maximizing Efficiency & Effectiveness

Maximizing Efficiency & Effectiveness

For quality control, all cervical photographs and treatment decisions were electronically sent to the central hospital, where doctors could review them at a later time. However, if a nurse needed an immediate consultation, she simply sent the doctor a text message. He could then download the photo on his smartphone and text a response. And all of this could happen while the patient was still in the examination room. This new procedure dramatically increased the ability of doctors to provide clinical supervision and oversight of patient care to nurses at multiple clinics.

The photographs were also useful for training purposes. The doctors and nurses reviewed all photographs on a weekly basis as a group, and over time their agreement about the diagnosis increased from 75 percent to nearly 100 percent. The nurses were now as accurate in their assessments as the seasoned doctors.11

While Dr. Parham has been one of the champions for calling attention to cervical cancer and working to combat it in Zambia, he certainly wasn’t working alone. He was joined and supported by a number of colleagues and friends throughout the country in clinical, government, business, and community settings. He had a strong Zambian team,12 and when a fellow gynecologist, Dr. Christine Keseba, became the First Lady of Zambia in 2011, she used her position to encourage women to get screened and for public and private partners to increase access to affordable cervical cancer screening. In addition, demand in the community was boosted by the team’s cancer and women’s health advocates, who led community awareness campaigns and provided community-based support to patients.

![]() Creating Demand

Creating Demand

Rather than build a stand-alone program in partnership with the Ministry of Health, the program was integrated into the HIV programs. This enabled the program to quickly increase access to care for women who were at highest risk. It also reduced infrastructure costs. All local staff were Ministry of Health personnel, helping ensure sustainability and government commitment to the program. Patients who needed additional services were referred within the public health system, further integrating the care system.

![]() Partner Coordination

Partner Coordination

Across the globe, Dr. Parham received ideas, support, and money from colleagues throughout Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America. The clinical leaders he trained throughout Africa became the technical expert advisors to help develop Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon, a public-private partnership to combat cervical and breast cancer. The partners committed $85 million to the effort. Engagement by the business community in health efforts such as these is not only the right thing to do, it makes good business sense.

Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon: A Public-Private Partnership to Combat Cervical and Breast Cancer

Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon is an innovative partnership to leverage public and private investments in global health to combat cervical and breast cancer—two of the leading causes of cancer death in women—in developing nations in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Led by the George W. Bush Institute, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Susan G. Komen for the Cure, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon expands the availability of vital cervical cancer screening and treatment—especially for high-risk HIV-positive women—and also promotes breast cancer education. Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon partners also work to de-stigmatize cancers and thereby lessen the shame that women with cancer experience; shame that prevents them from getting care early.

The partnership leverages the platform and resources of PEPFAR, established under President Bush and a cornerstone of President Obama’s Global Health Initiative (GHI). The partners include Merck and GSK, the pharmaceutical firms that manufacture the commercially available vaccines that can prevent HPV infection in most cases; Becton Dickinson, a multinational supplier of medical equipment, supplies, and technologies; Caris Life Sciences, a pathology diagnostic firm; QIAGEN, the firm that manufactures careHPV, an HPV diagnostic test; the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation; and IBM. The Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon partners and others provide technical guidance, advocacy, and donated or discounted products and services to help countries combat cervical and breast cancer.13

New Solutions for Cervical Cancer

The doctors in Zambia were not the only or the first ones to work on this problem.14 Nor has their innovative approach been the only method tried and tested. With financial support from the Gates Foundation, PATH created a partnership with Digene (now QIAGEN, a corporation that develops and markets diagnostic tests), to develop a new low-cost test to detect HPV DNA. Their product, careHPV, allows for screening of women en masse—a whole village or community at a time.

![]() Innovation & Entrepreneurship

Innovation & Entrepreneurship

With visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), providers must test each woman one by one. It’s a good option when testing populations who are known to be at high risk for HPV, such as women with HIV. However, all sexually active women are at risk for developing cervical cancer, and the vast majority will not have HIV. In certain contexts it may be more efficient to screen large groups of women for HPV and then do VIA on just the women who are found to be positive for HPV. This method shifts the procedure from the provider to the patient.

With careHPV, cells from the vagina are collected with a soft brush-like applicator, placed in a container, and taken to a laboratory. The procedure can be done by a provider in a clinic as well as by a patient in the privacy of her home. Only if the sample is positive will she be required to have the VIA procedure. Once approved for self-collection of the sample by the patient, this product may be able to reduce the workload of providers significantly.15

In addition, the potential to dramatically reduce cervical cancer deaths in developing countries in the future received a major boost when the GAVI Alliance, the public–private partnership discussed in chapter 4 that helps countries stimulate demand for vaccines, agreed to work with developing countries to prepare for the introduction and scale-up of the vaccine against HPV. GAVI estimates that through its support, more than 30 million girls will be immunized against HPV by 2020.16

Since the Zambian Ministry of Health’s cervical cancer program was launched in 2006, almost 100,000 women have been screened for cervical cancer, and it is beginning an HPV vaccination campaign with support from Merck. In addition, over 200 health care professionals from ten African countries have been trained in cervical cancer screening and treatment in Zambia. The cervical cancer prevention program has thus far been replicated in eight of them.17

Aids for Controlling AIDS

The progress that is being made in fighting cervical cancer builds off the progress that has been made in HIV/AIDS care and leverages its vast infrastructure. In less than a decade, the number of new HIV infections each year decreased nearly 15 percent, while the number of people on antiretrovirals skyrocketed more than twenty-three-fold.18

But without continued commitment, the gains made may be short-lived. HIV/AIDS has been devastating communities around the world for several decades, taking the lives of nearly 1.5 million people each year—more than 25 million people in the past thirty years.19 Sub-Saharan Africa is the hardest-hit region, accounting for over two-thirds of the 34 million people affected by AIDS, though it has only 15 percent of the world’s population.20

Despite the magnitude of the problem, and despite the hurdles and setbacks, we have made significant strides in combating HIV/AIDS across the globe. Over 8 million people now receive anti-retroviral treatment (ARVs), dramatically extending lives.21 In addition, ARV treatments that cost $10,000 per year when they first appeared and were horribly complicated to use are now incredibly simple combination ARVs, and most basic regimens cost less than 4% their original price in developing countries. This achievement was due to the efforts of many public and private partners to push down drug prices, including pharmaceutical entrepreneurs in Brazil and China, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and UNITAID.22 In addition, the simplified combination ARVs made it easier for patients to stay adherent, which improves outcomes.23 This simplification has also made it possible to shift the administration of ARVs to nurses in rural communities.

With the creation of antiretroviral drugs, solutions to combat HIV exist, but not everyone is getting treated. Seven million people in low- and middle-income countries still do not receive any sort of treatment for HIV, including 44 percent of those in Sub-Saharan Africa, 56 percent of people in Asia, 77 percent of people in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and 87 percent of people in the Middle East.24

To increase the reach of programs, HIV care can be integrated into primary medical care, which creates synergies, reduces redundancies, and helps ensure sustainability. In Zambia, for example, integrated care has resulted in an increase in the new cases of HIV identified. If you are at a clinic for some other health problem, you may be willing to be tested for HIV while you’re there. This may increase the chance that more patients can be tested, since the stigma associated with coming in to be tested specifically for HIV is reduced. When HIV testing was done in the general medical sector in Zambia, 53 to 58 percent of those who came in for other health issues accepted HIV testing; 13 to 24 percent of those tested were found to be HIV positive.25

![]() Scaling

Scaling

Integrating HIV into general medical services in Mozambique resulted in improved HIV testing, increased efficiency in getting people on ARVs, better patient compliance, and more geographic access to HIV services.26 The benefits are significant, which suggests that integration of HIV into general medical services may provide an effective path to success. However, general primary care services are often short-staffed and underfunded.27 Task-shifting, so that basic checkups and medication refills are more efficiently performed, and using checklists, which improves compliance, efficiency, and quality of care, could solve these problems. Task shifting to the general medical system could take place without imposing great costs on the system, improving both the general health care system and HIV care, provided that safeguards are in place.

While there have been significant advances in HIV prevention and treatment, there remain significant challenges that can be addressed with our IMPACTS approach. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatments from doctors to nurses has been successful. In order to scale up access to care, treatment must now be shifted from HIV specialty sectors to the general medical sector.28

Champions have been critical in helping to create demand for controlling HIV throughout the world. When Americans think of who or what has helped call attention to HIV, depending on their age, they may think of Magic Johnson, Ryan White, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP!), or a teacher, a parent, a minister, a friend, a movie, or a TV show. Likewise, when Africans think of HIV leaders, they may mention President George W. Bush, who initiated PEPFAR, or Nkosi Johnson, a South African boy born with AIDS, who was keynote speaker at the International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, in 2000. He ended his speech with the statement: “Care for us and accept us—we are all human beings. We are normal. We have hands. We have feet. We can walk, we can talk, we have needs just like everyone else—don’t be afraid of us—we are all the same!”29 Nkosi helped put a face on AIDS in Africa and stimulated more calls for action and treatment among Africans before he died at the age of twelve.

![]() Creating Demand

Creating Demand

Some attribute the progress that has been made in the control of infectious diseases to the fact that there have been champions, and the lack of similar progress in other areas such as noncommunicable disease to the lack of champions. Champions have been needed at all levels to create demand, stimulate supply, encourage innovation, build new markets, increase access, improve quality, and lower costs. To reduce deaths and dramatically increase access to care for the poor, new leaders will be needed to call attention to the problem and to show the way.

Mobile Technology

The use of mobile technology to greatly improve access and quality control has been key in controlling infectious disease amid a variety of conditions. It has been used to improve HIV prevention efforts; disease diagnoses, care, and treatment; maternal labor and delivery; vaccination rates; and child health outcomes in low-resource settings.30 In developing countries, mobile technology has been a critical component of task shifting, reducing medication stockouts, and confirming the provenance of medications.31

One of the most difficult problems with malaria control is ensuring that medications are available where and when they are needed—often a major problem in hard-to-reach rural areas that may run out of supplies before the next shipment arrives. Very sick patients can’t get well if they can’t get their medications, and donors lose confidence. To solve these problems in Tanzania, SMS for Life, a public-private partnership among Novartis, IBM, Vodafone, the Roll Back Malaria Partnership, and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Tanzania, was developed.32 Clinics are sent weekly staff reminders to check for supplies of malaria medications. Clinic staff responds with the requested information, and they are rewarded for doing so with free airtime on their cell phones.

The centrally stored information then allows the central manager to modify future delivery of supplies to the clinic or to send additional supplies before the next planned delivery. The program has reduced stockouts for all malaria medications in 129 health facilities from 78 percent to 26 percent per month over twenty-one weeks.33 The project was so successful that it is now being used by more than 5,000 clinics in Tanzania, and it has been expanded to additional countries and to include the monitoring of many critically important health supplies.34 An effort in Uganda enhanced this system by crowd-sourcing stockouts. It allows patients to anonymously text in if they experienced a stockout when they sought care. This type of crowd sourcing not only engages and gives communities voice, but creates a way of alerting health officials when essential medicines are missing.35

Another important application of mobile phone technology is ensuring the quality of medications. Counterfeit medication is a big problem in many developing nations. Each year 700,000 people die because they are given medications that look real but are substandard. It is estimated that counterfeit medications account for 35 percent to 75 percent of medications for some conditions consumed in lower-income countries.36 At best, a patient remains ill. At worst, the patient spreads an infectious disease to many others before dying. To combat this problem, a consortium of African telecom operators, pharmaceutical associations, technology companies, and philanthropies created the mPedigree Network.

With mPedigree, a verification sticker is placed on the back of legitimate medications. Prior to purchasing the medication, the patient scratches off the sticker and sends a text message to a secure server to verify that the medication is legitimate. Once the medication has been verified, the patient then purchases it. Other companies that also have text-message verification systems include PharmaSecure, Kezzler, and Sproxil. This initiative has been rolled out in many developing countries.

Rapid Diagnostics for Infectious Diseases

The VIA procedure takes a nurse only five minutes to determine whether a woman may have precancerous cervical lesions and enables her to be treated on the spot. Similarly, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have greatly increased the ability to shift the tasks of diagnosing and treating many conditions and diseases from high-skilled personnel to lower-skilled ones and from clinical settings to nonclinical ones. Like home pregnancy tests, the ready availability of these tests greatly facilitates the ability to diagnose disease in local communities where people live.

There are now rapid diagnostic tests for over thirty conditions, including malaria, HIV, syphilis, tuberculosis, and hepatitis B.37 The rapid diagnostic tests for infectious diseases are generally very easy to use, require little training, and can facilitate on-the-spot treatment. Some do require subtle interpretations; however, a group at UCLA has developed a smartphone application to help take out the guesswork for some tests.38

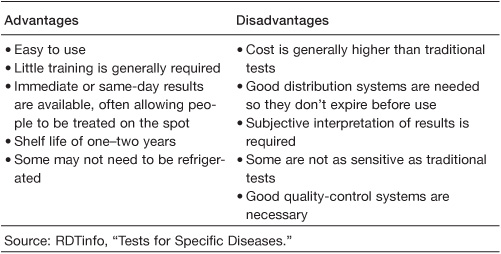

RTDs are generally more expensive than traditional tests, and their costs are often prohibitive in very low-resource settings (see Table 11). However, with the growing demand for rapid diagnostic tests due to task shifting from clinics to community settings, it is likely more manufacturers will enter the market, increasing competition and introducing economies of scale that may reduce prices and improve access.

Table 11 Advantages and Disadvantages of Rapid Diagnostic Tests

Goliath Gets Up

We have inexpensive solutions to control infectious diseases. People in developing countries do not have to fall like Goliath. Whether it’s a drop of vinegar or integrating specialized services into the general health care system, solutions do exist and can be brought to those who most need access to high-quality care at low cost. As with any disease, the first choice should be to take preventive measures, such as encouraging use of condoms to reduce the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. The number of rapid diagnostics is increasing, and mobile technologies are being used to enable task shifting while maintaining quality of care. All of this is making it increasingly possible to task-shift, scale up, and spread out health care to improve access, quality, and use, all while reducing costs. The IMPACTS approach will help us bridge the final mile in health care to finally defeat the scourge of infectious diseases ravaging the developing world.

Food for Thought

• What three organizations might help you achieve greater impact or scale (including government, NGOs, businesses, donors, and others)? How might you also help them? How might you engage them in this work over the next year?

• What might you do to ensure that the quality of shifted tasks remains high (for example, training, supervision, mobile phone applications, checklists, or incentives)? How will you know if you’ve succeeded?